Moscow's new red line in Ukraine, spheres of influence in a multipolar world, the side effects of sanctions on Russia, and more.

RED LINE

What Putin's nuclear threat means for Russian and U.S. policy in Ukraine

In a belligerent speech which aired on Wednesday, Russian President Vladimir Putin cast his invasion of Ukraine as a defense of the "sovereignty, security, and territorial integrity of Russia," accusing the West of plotting to break up his country and raising new fears of nuclear war. Here's what happened and what it means for U.S. policy.

Putin's red line

Putin said his goal is "to liberate the whole of Donbas" and claimed the contested peninsula of Crimea as Russian land. [WaPo]

He announced plans for an expanded military mobilization, which Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu later clarified involves calling up about 300,000 reservists. [Politico / Zoya Sheftalovich]

Putin alluded to his nuclear arsenal and promised that in "the event of a threat to the territorial integrity of our country and to defend Russia and our people, we will certainly make use of all weapon systems available to us. This is not a bluff." [WaPo]

In a U.N. speech, also on Wednesday, President Joe Biden responded by pledging "solidarity" with Ukraine and condemning Moscow's "overt nuclear threats against Europe." [AP]

The nuclear risk

How likely is Putin to make good on his nuclear threat? The New York Times' Ross Douthat analyzed the question in his Sunday column:

Putin's speech recommitted to "conventional conflict. But the nuclear threat has always been linked to Russian desperation" and this "was undoubtedly a desperate act."

Putin "was explicit ... that a full collapse simply would not be permitted, even if that required the use of nuclear arms."

That red line means that if "the war continues on its current trajectory," Moscow's "bluff will be called, and it will face an immediate choice between the nuclear option and defeat."

What happens then? We just don't know. But we do know "there is a point at which Ukraine's goals and America's interests may diverge."

Implications for U.S. policy

"Nuclear confrontations are typically contests of will. It is simply the case that states care more about what happens in their side and back yards than do their opponents farther afield." [DEFP / Barry Posen]

Whatever happens in Ukraine, the U.S. remains "a rich and insulated great power surrounded by ocean moats—not to mention possessing a large nuclear arsenal." [DEFP / Joshua Shifrinson]

As Douthat noted, "U.S. interests are not identical to Ukraine’s, and U.S. policies should prioritize aiding Ukraine in its defense while avoiding escalation and expansion of the war." [DEFP / Daniel L. Davis]

► Go deeper with a DEFP explainer: American interests in the Ukraine war ◄

CHARTED

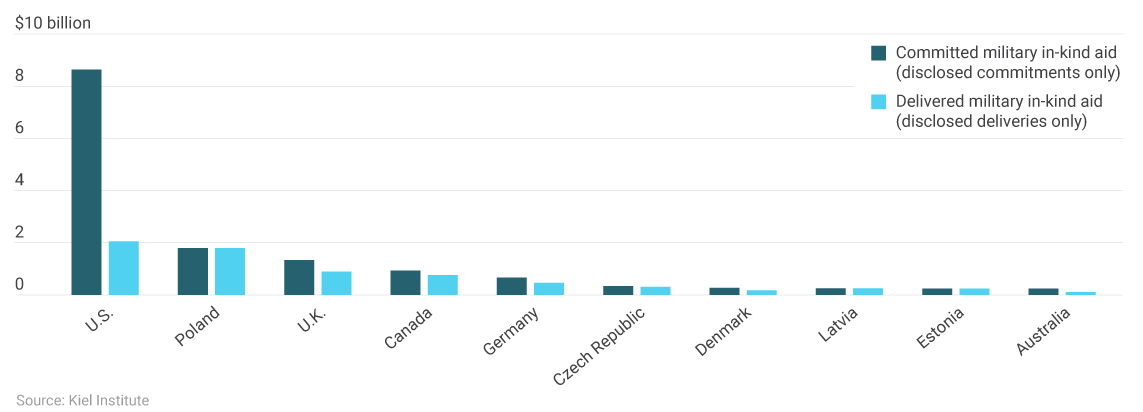

Top state support for Ukraine: committed vs. delivered weapons

U.S. military in-kind aid to Ukraine far exceeds that of other nations and the European Union, particularly if we account for future aid commitments.

NEW EXPLAINER

Spheres of influence in a multipolar world

"The relevant question now ... is not if the transition to a world of multiple spheres of influence will take place (given the structural changes at the level of international order, it most certainly will), but how Washington should manage this development in ways that are both realistic and conducive to U.S. interests." [DEFP / Andrew Latham]

SANCTIONS

The collateral damage of a long economic war [Foreign Affairs / Nicholas Mulder]

"Over the last six months, 38 Western and Asian states have leveled a growing barrage of sanctions against Russia."

"But although Fortress Russia was breached, it has so far neither collapsed nor surrendered." The Ruble rebounded to pre-war levels by April, and the oil industry has recovered.

Meanwhile, civilians in uninvolved countries including Bangladesh, El Salvador, Egypt, Ghana, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Tunisia are suffering consequences of anti-Russian sanctions.

"Historically, sanctions have the highest chance of producing major policy change when a political movement can act as a vehicle for popular mobilization." Russia doesn't have that.

If this becomes a long war, then, "the costs of this economic war will be borne mainly by weaker economies in the global South" while doing little to nothing to force Moscow to change course in Ukraine.

TRENDING

Let's be honest about the Iran nuclear deal

'Huge problem': Iranian drones pose new threat to Ukraine

Diplomacy is still (just about) possible in Ukraine

The one key word Biden needs to invoke on Ukraine

Chinese foreign minister meets with Secretary of State Blinken

Home to 28,000 U.S. troops, South Korea unlikely to avoid a Taiwan conflict