Key points

- Throughout the modern era, great powers have routinely staked out geographic zones within which they have limited the autonomy of weaker states—often as buffer zones between themselves and potential adversaries or rival empires. Since the nineteenth century, these geopolitical spaces have typically been referred to as spheres of influence.

- The specific configuration of such spheres depends largely on the distribution of power in the international system. During moments of multi-polarity, multiple great powers will attempt to assert spheres of influence; during the Cold War era of bipolarity, the international order was defined by two superpower-dominated spheres; during the post-Cold War moment of unipolarity, the U.S. alone was able to assert a sphere of influence.

- Given this, it was inevitable that the return of multipolarity from the 2010s on would result in the crystallization of a new, multipolar, configuration of spheres of influence—one involving multiple great powers each asserting their own sphere.

- The relevant question now, therefore, is not if the transition to a world of multiple spheres of influence will take place (given the structural changes at the level of international order, it most certainly will), but how Washington should manage this development in ways that are both realistic and conducive to U.S. interests.

- The most realistic answer to this how question is to adopt a differentiated strategy that recognizes that, while the U.S. will not be able to prevent spheres of influence as a feature of international order tout court, it may be able to thwart specific spheres in certain specific circumstances.

What are the spheres of influence?

Throughout the modern era, great powers have routinely staked out geographic zones within which they have limited the autonomy of weaker states—sometimes as buffer zones between themselves and potential adversaries or rival empires and sometimes merely as a means of shaping the dominant states immediate environment for its benefit. Since the nineteenth century, these geopolitical spaces have typically been referred to as spheres of influence.

Technically, a sphere of influence is a determinate region within which a predominant external power seeks to both (a) limit the political independence of weaker states within it, and (b) prevent other external powers from exercising similar influence.1Andrew Hurrell, “Sphere of Influence,” The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics, (3rd ed., 2009). “For the region to qualify as a sphere of influence, the level of control the influencer has over the weaker states or entities must be below the threshold of direct imperial or colonial control yet above that of mere alliance or coalition leader.”2Amitai Etzioni, “Spheres of Influence: A Reconceptualization,” The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs 39, no. 2 (Summer 2015): 117-132. See also Van Jackson, “Understanding Spheres of Influence in International Politics,” European Journal of International Security 5, no. 3 (October 2020): 255–273.

Spheres of influence are a structural feature of all anarchic international orders. Under conditions of anarchy—i.e., in a world lacking a supreme authority or global sovereign capable of resolving disputes, enforcing law, and imposing order—all states face systemic pressures to maximize their power and security. Responding to these pressures, more powerful states (i.e., “great powers”) will seek to extend their influence over less powerful states in order to extract resources and/or to create buffer zones between them and other great powers that are similarly seeking to enhance their power and security. To the extent that the resulting geopolitical spaces fall short of direct imperial or colonial control yet above that of mere alliance or coalition leader, they can be said to constitute a sphere of influence.

While a ubiquitous feature of great power competition under conditions of anarchy—indeed a near-universal aspect of international relations—spheres of influence can vary considerably with respect to several key characteristics.

To begin with, they can vary according to the degree of influence the predominant power exerts over the lesser powers within its sphere. Minimally, the predominant power within a sphere of influence will merely seek to exclude other great powers from exerting influence in its sphere. More maximally, however, the predominant power within a sphere of influence will seek to shape both the foreign policy and the domestic political and economic systems of subordinate states.

Spheres of influence can also vary according to “recognition.” Simply put, a state’s sphere of influence may be recognized by other powers formally, informally, or not at all.

- A formal sphere of influence involves explicit agreement amongst states regarding the boundaries, nature, and limits of specific spheres. An example of this would be the spheres established in the period following the Conference of Berlin (1884–1885), with the 1907 Anglo‐Russian convention concerning Persia providing perhaps the most illustrative example.

- An informal sphere of influence, on the other hand, is one that is not codified in an explicit agreement. An example would be the United States’ historical sphere in the Western Hemisphere, which was never formalized via treaty or other international accord at any point during the nineteenth century.

- And, of course, there are cases where an asserted sphere of influence is simply not recognized—either formally or in practice—by other great powers. An example of a claim to a sphere of influence that is largely unrecognized is Russia’s contemporary claim to a sphere that includes Ukraine.

Finally, spheres of influence vary according to stability.3Evan R. Sankey, “Reconsidering Spheres of Influence,” Survival 62, no. 2, (March 2020): 41. History suggests that stable—i.e., less war-prone—spheres have the following characteristics:

- They have unambiguous boundaries, the limits of which are clearly understood by the predominant power, the subordinate power(s), and all external powers;

- they are dominated by powers that actually have the means to shape the foreign and/or domestic policies of the subordinate state and to exclude other external powers from exercising influence over that state;

- they contain subordinated states that accept their subordinate status;

- they do not overlap with spheres asserted by other great powers; and

- they are recognized, either formally or informally, by other great powers.

Spheres of influence lacking one or more of these traits tend to be less stable and thus more war-prone.

The history of spheres of influence

As a mechanism for managing great power competition, spheres of influence have a history going back at least to the sixth century BCE when Rome and Carthage concluded a treaty prohibiting Roman ships from sailing near Carthaginian waters and Carthaginian forces from attacking towns friendly to Rome. They have subsequently featured prominently in the strategic competitions between Rome and Persia, Athens and Sparta, and countless other kingdoms and empires right down to the modern era. Indeed, spheres of influence have been a near-ubiquitous element of international order throughout recorded history.

Despite their near ubiquity, the form and function of spheres of influence is not the same across time and space. As with all such mechanisms, spheres have tended to bear the imprint of the unique historical circumstances out of which they arose and within which they operated.

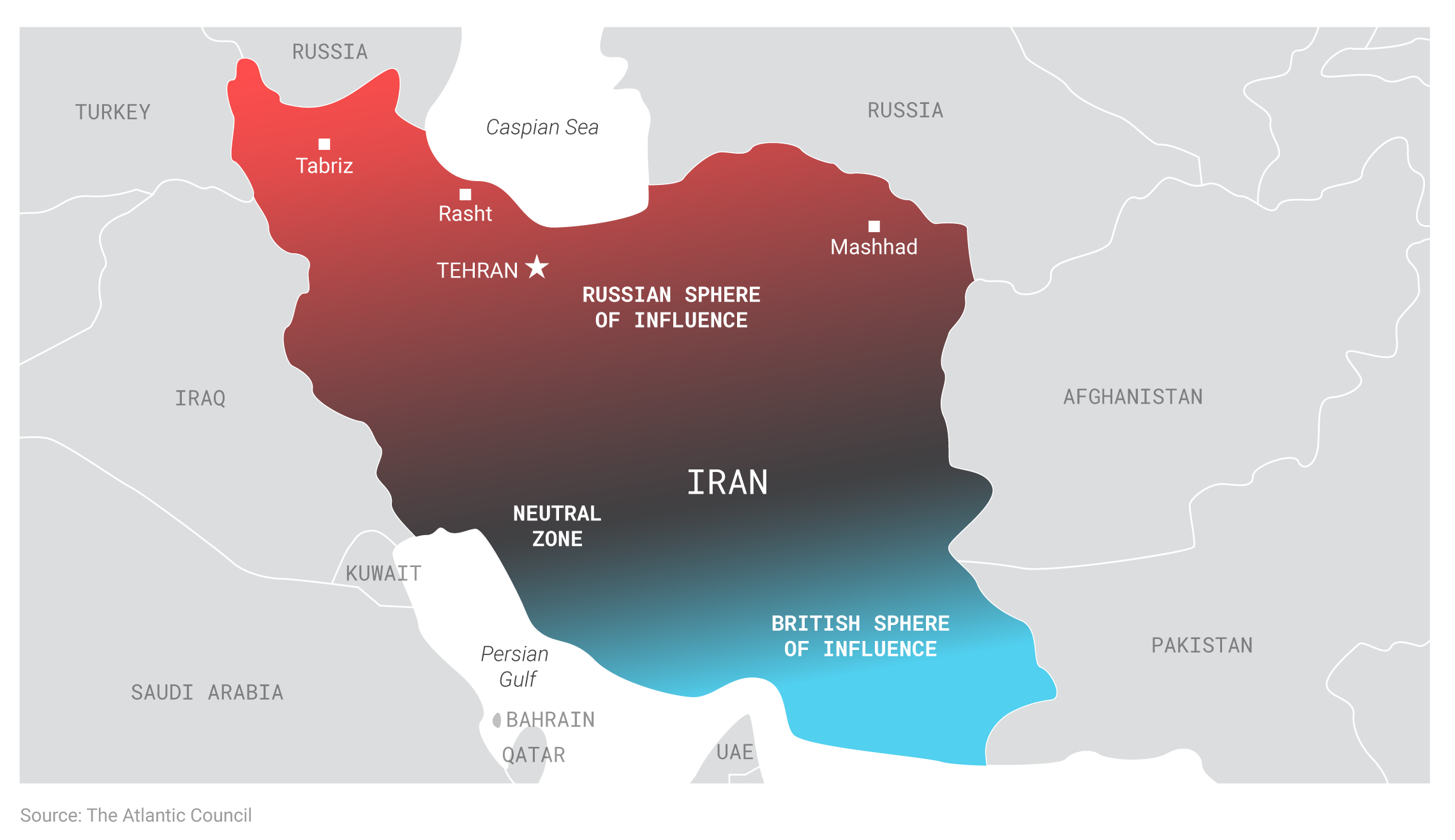

Sphere of influence in Iran after the 1907 Anglo-Russian Convention

The 1907 Anglo-Russian convention is an example of an agreement between countries to establish formal spheres of influence in contested neighborhoods to deconflict and reduce tensions.

So, for example, in the modern era, spheres of influence evolved in ways that reflected the historically specific character of interstate and inter-imperial rivalry from the nineteenth century into the first half of the twentieth. During this era, spheres of influence served two basic functions, both related to the core dynamics of the then-prevailing international order.4Susanna Hast, Spheres of Influence in International Relations (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2014), ch. 2.

First, spheres sometimes evolved to enable European powers to exercise a less direct form of imperial control and exploitation over non-European societies. In such arrangements, the lesser power’s formal sovereignty was recognized and affirmed, even as the predominant power exercised considerable and exclusive informal control over the lesser power’s political and economic systems. In this sense, some spheres of influence were in fact quasi-formal mechanisms of colonial rule—mechanisms that did not involve outright annexation or direct political control, but that nevertheless subordinated the weaker powers politically and facilitated their economic exploitation.5An example of this was the U.S. sphere asserted over the Western Hemisphere during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Following the declaration of the Monroe Doctrine in 1823, Washington worked to achieve military dominance throughout the Western Hemisphere, exclude extra-hemispheric powers from the region, subordinate the sphere’s lesser powers geopolitically and economically, and on occasion even to directly influence the internal politics of other the countries within the sphere. The European use of unequal treaties and long-term leases to impose zones of informal colonial subordination on nineteenth century Qing China is perhaps the prime example of this type of sphere. Although not the case in China, such spheres of influence could evolve into more formalized “protectorates” and subsequently even into formal colonies.

Second, spheres of influence sometimes evolved as a mechanism for managing inter-imperial rivalry and mitigating the danger of war. In this form, spheres served to deconflict European imperial projects in Africa and Asia by formally or informally demarcating the limits of each. Typically, this involved one imperial power conceding to another exclusive influence over a potentially contested territory on the frontier between them, thus removing a potential casus belli.

This form of sphere was first explicitly invoked by Russian Foreign Minister Alexander Gorchakov in an 1869 letter to British Foreign Secretary Lord Clarendon. In the letter, Gorchakov formally assured London that Afghanistan—a potential inter-imperial flash point—lay “completely outside the sphere within which Russia might be called upon to exercise her influence.”6Evan N. Resnick, “What’s Missing in the Debate Over Spheres of Influence,” Chatham House, March 2020, https://americas.chathamhouse.org/article/whats-missing-in-the-debate-over-spheres-of-influence/. His intent was to reassure the British regarding their vital interest in India and thus reduce tensions between Britain and Russia. A similar logic lay behind the signing of the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907, which reaffirmed Russia’s promise to stay out of Afghanistan and divided Persia (a potential buffer zone for both the British and Russian empires) into British and Russian spheres, thus ending Anglo-Russian inter-imperial rivalry in Central Asia and enabling them to cooperate in balancing against a rising Germany.

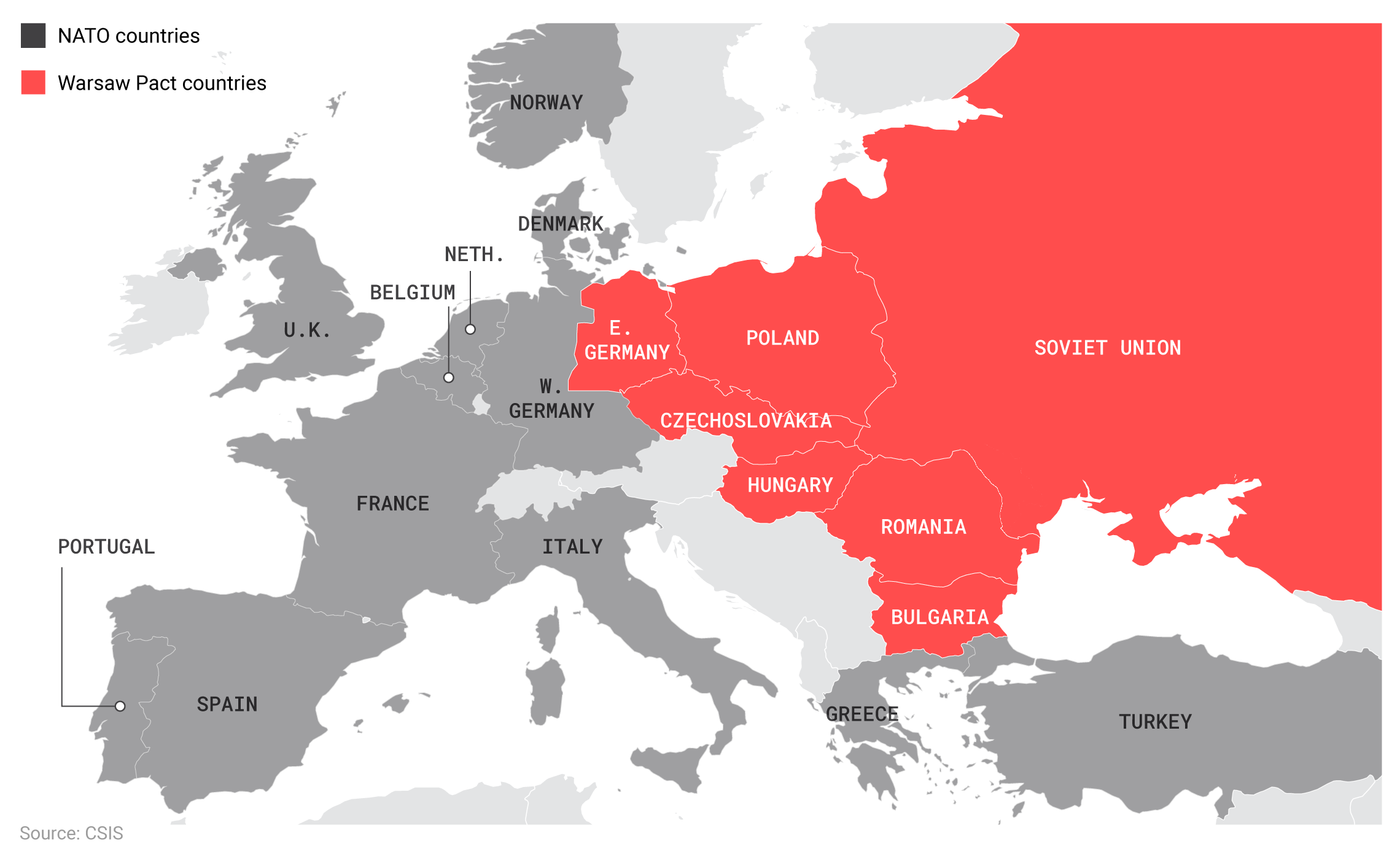

In the post-WWII era, spheres of influence evolved in a different direction, this time reflecting the new realities of bipolar superpower competition in a nuclear world. In this new context, spheres were less about exercising imperial control or managing inter-imperial rivalry than about stabilizing Soviet-American geopolitical relations under conditions of mutual nuclear vulnerability and ideological hostility. During the Cold War, spheres of influence took the form of ideologically determined blocs dominated by one or the other of the two superpowers. For the most part, each superpower conceded to the other its inner or core sphere of interest while contesting—sometimes quite vigorously—those asserted over more peripheral countries. Functionally, the mutual recognition of Cold War spheres in Europe and (for the most part) the Western Hemisphere served to reassure both superpowers that their core interests were not threatened, thus reducing the prospect of direct military conflict and (potentially) nuclear war.7Paul Keal, Unspoken Rules and Superpower Dominance, (London: Macmillan, 1983). This mutual recognition also generated clear red lines of acceptable and unacceptable behavior. By recognizing each other’s sphere of influence, both Moscow and Washington acknowledged that the other would respond aggressively to any challenge to their dominance within their sphere. This, in turn, disincentivized such challenges and decreased the likelihood of war.

While the primary function of Cold War spheres of influence was to decrease the frequency of superpower crises and moderate the intensity of such crises as did occur, they also served important secondary functions. Among the more important of these was that they helped pacify relations among subordinate states within them.8Lindsay O’Rourke and Joshua Shifrinson, “Squaring the Circle on Spheres of Influence: The Overlooked Benefits,” The Washington Quarterly 45, no. 2 (July 2022): 105–124. Both the Soviet Union and the United States were able to minimize the intensity of the security dilemma within their respective spheres, thus eliminating one of the major causes of war in what had historically been a very war-prone region.

Cold War spheres of influence in Europe

The Cold War balance between east and west in Europe kept the peace for 50 years and proved instrumental in the United States prevailing over the Soviet Union.

The end of history, the end of spheres of influence?

During both the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, then, spheres of influence evolved in response to systemic pressures generated first by great-power rivalry and later by superpower competition. They were functional adaptations to the dynamics of multipolar and bipolar competition in that they reduced the possibility of war and thus contributed to the overall stability of the international order.

During the subsequent era of unipolarity, however, the specific systemic pressures that had given rise to the two superpower dominated spheres during the Cold War era largely evaporated. As Cold War competition gave way to the universalization of the U.S.-led liberal international order, spheres of influence evolved yet again, this time reflecting the new realities of U.S. hegemony in a globalizing world. In this new context, the logic of spheres was less about managing multipolar imperial rivalry, or about stabilizing Soviet-American geopolitical relations under conditions of mutual nuclear vulnerability and ideological hostility, than it was about sustaining and expanding the so-called “liberal international order.” During the post-Cold War era, a system defined by two spheres based on ideologically determined blocs dominated by the two superpowers gave way to one defined by a single, world-wide sphere of influence dominated by the sole remaining superpower, the United States. For the most part, other states conceded—or at least did not actively challenge—Washington’s assertion of this planetary sphere of influence. Functionally, this new unipolar-sphere arrangement both reflected the underlying structure and logic of the Liberal International Order and licensed U.S. intervention against “rogue states” or illiberal non-state actors that threatened that order. During this era, non-U.S. spheres did not disappear entirely, of course. Russia, for example, asserted a residual sphere of influence in its “near abroad.”

At the same time, the constructive role played by spheres of influence in managing great power competition in the past was largely forgotten. According to the liberal internationalist conventional wisdom prevailing in this era, such spheres were little more than dangerous atavisms—relics of a benighted past that had no place in the enlightened liberal international order of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice perhaps best summarized this new perspective when she described the post-Cold War order as one “in which great power is defined not by spheres of influence or zero-sum competition, or the strong imposing their will on the weak—but by open competition in global markets, trade and development, the independence of nations, respect for human rights, governance by the rule of law, and the defense of freedom.”9Condoleeza Rice, “Secretary Rice Addresses U.S.-Russia Relations at The German Marshall Fund,” U.S. Department of State, September 18, 2008, https://2001-2009.state.gov/secretary/rm/2008/09/109954.htm.

The reason for this act of forgetting is perhaps obvious. Despite having carved out its own sphere of influence in the Western Hemisphere during the nineteenth century, for most of American history, U.S. leaders have generally opposed the idea of an international order divided into rival spheres—and have denied that the United States is implicated in any way in upholding such an order.10Hal Brands and Charles Edel, “The Disharmony of the Spheres,” Commentary, January 2018, https://www.commentary.org/articles/hal-brands/the-disharmony-of-the-spheres/. This being the case, it is hardly surprising that at precisely the moment when the Soviet sphere of influence had largely disappeared, and when the U.S. sphere was being characterized as something very different, they were inclined to deny both that spheres of influence had ever played a positive role in international politics and that they could ever play such a role in the future.

The return of multipolar great power competition

Just as the multipolar international/inter-imperial system of the nineteenth gave way to the bipolar system of the post-WWII era, and the era of Cold War bipolarity then gave way to post-Cold War unipolarity, so the unipolar moment has now given way to a new era of multipolar great power competition.11Michael J. Mazzarr, Understanding Competition: Great Power Rivalry in a Changing International Order— Concepts and Theories, (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2022); Elbridge A. Colby and A. Wess Mitchell, “The Age of Great-Power Competition: How the Trump Administration Refashioned American Strategy,” Foreign Affairs, January/February 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/age-great-power-competition. While this new era may be defined in part by the institutional residues of post-Cold War U.S. dominance, it is primarily defined by the end of unipolarity—that is, by:

- the erosion of U.S. military primacy;

- China’s emergence as a global power;

- Russia’s persistence as a (diminished) great power;

- the emergence of other powers (like India) that are not only dominant players or aspiring hegemons in their home regions, but increasingly willing and able to shape global politics more broadly; and,

- the erosion of the ordering mechanisms (rules, norms, and institutions) associated with the post-war liberal international order (recently rebranded as the rules-based international order).

As this transition has taken place, a new configuration of spheres has begun to crystallize. Specifically, in the current era—while pressures to manage inter-imperial rivalry (specific to the late nineteenth century), to sustain ideologically defined blocs (specific to the Cold War era), and to unilaterally police the liberal international order (specific to the post-Cold War era) have all dissipated—the deep systemic pressures to exclude potentially dangerous competitors from one’s periphery and to shape regional economies in one’s favor have not. They remain as powerful as ever, though now they reflect the emerging realities of multipolar great power competition.

While this historical transition is in its infancy, the broad contours of a multipolar world at least partly defined by the presence of spheres of influence are already apparent.12The most prominent proponent of embracing a return of SOIs is Graham Allison, “The New Spheres of Influence.” Foreign Affairs, February 10, 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-02-10/new-spheres-influence.

First, the evolving realities of the contemporary world order are such that great powers like Russia and China (and perhaps others in the future) are inevitably going to assert spheres of influence in pursuit of their core economic, political, and strategic interests. These spheres may or may not be limited to a country’s “near-abroad” or “backyard.”

Second, there is little the United States can do to prevent current and future great powers from establishing spheres of influence. States seeking to assert a sphere in pursuit of core economic or geopolitical interests are typically willing to invest considerable resources, and take significant risks, both to exert influence within their sphere and to exclude other powers from it. Given the United States’ specific national security interests in the “backyards” of these states are usually relatively weak, the resulting “commitment asymmetry” is such that the United States is unlikely to be willing or able to do much to deter or prevent these states from asserting their spheres of influence.13Sankey, “Reconsidering Spheres of Influence.”

Third, the return of spheres of influence can have positive strategic consequences—both for the United States and for international order more broadly. These include:

- establishing red lines of acceptable and unacceptable behavior for both sides, thus limiting potential flashpoints;

- creating buffer zones around asserting states’ peripheries, thus reducing the fear of encirclement and the associated risk of war;

- focusing Washington’s attention on securing the United States’ sphere, thus limiting the scope of U.S. strategic commitments, and better aligning them with its capabilities; and,

- circumscribing the freedom of action of subordinate states, thus limiting their ability to draw the predominant power into conflict with other great powers.14For a fuller discussion see O’Rourke and Shifrinson, “Squaring the Circle on Spheres of Influence: The Overlooked Benefits.”

Finally, given both the inevitability of spheres of influence and the ordering benefits they can provide, the United States’ best strategy is to acknowledge their existence as a permanent fixture in international politics and then work to ensure that each specific sphere meets the criteria for stability laid out above.15There are, of course, those who argue that the return of SOIs is neither inevitable nor desirable. See Steven Pifer, “Contending With—Not Accepting—Spheres of Influence,” Russia Matters, March 5, 2020, https://www.russiamatters.org/analysis/contending-not-accepting-spheres-influence; Robert Kagan, “The United States Must Resist A Return to Spheres of Interest in the International System,” Brookings February 19, 2015, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2015/02/19/the-united-states-must-resist-a-return-to-spheres-of-interest-in-the-international-system/; Hal Brands and Charles Edel, “The Disharmony of the Spheres,”; and, Hal Brands, “Don’t Let Great Powers Carve Up the World,” Foreign Affairs, April 20 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2020-04-20/dont-let-great-powers-carve-world.

Toward a differentiated approach to spheres of influence

The hard reality, then, is that the end of unipolarity and the return of multipolar great power competition simply assures that some states will respond to systemic pressures by attempting to assert their influence over other states. The relevant question therefore is not if the transition to a world of multiple spheres of influence will take place (given the structural changes at the level of international order, it most certainly will), but how Washington should manage such an inevitable development in ways that are both realistic and conducive to U.S. interests.

The most realistic answer to this how question is to adopt a differentiated strategy that recognizes that, while the United States will not be able to prevent non-U.S. spheres of influence as a feature of international order tout court, it may be able to thwart specific spheres in certain specific circumstances.

Such a strategy, of course, would be premised first on an ability to discern when—i.e., under what conditions—another state’s assertion of a sphere of interest is so inimical to U.S. interests that the United States simply has no choice but to oppose it. In the abstract, such conditions can be said to obtain when the creation of a sphere by a rival great power will result in:

- the economic exclusion of the United States from a key region of the globe;16Brands, “Don’t Let Great Powers Carve Up the World.”

- a shift in the balance of power in a strategically significant region that threatens key U.S. interests;

- compromising the United States’ own sphere; or,

- a direct threat to the security of the United States homeland.

Additionally, a differentiated strategy must be premised on an ability to distinguish between those cases where it may be possible to thwart the efforts of another great power to assert a sphere of influence and those where such efforts are likely to prove futile—or worse.

At the risk of oversimplification, cases in which it may be possible to forestall the emergence of a sphere of influence are likely to involve:

- a regional balance of power that does not favor the asserting power;

- either a rough asymmetry of commitment or a “balance of commitment” that does not favor the asserting power; and,

- the presence of lesser powers within the asserted sphere that are willing and able to resist efforts to impose a sphere.

Where these conditions prevail, there is no reason for the United States to concede the claims of the asserting power. Indeed, they constitute the conditions-of-possibility for a restrained “balancing strategy”—that is, a strategy that is carefully calibrated to blunt the asserting power’s efforts to impose a sphere of influence without seeking to establish or maintain an American sphere in its place.

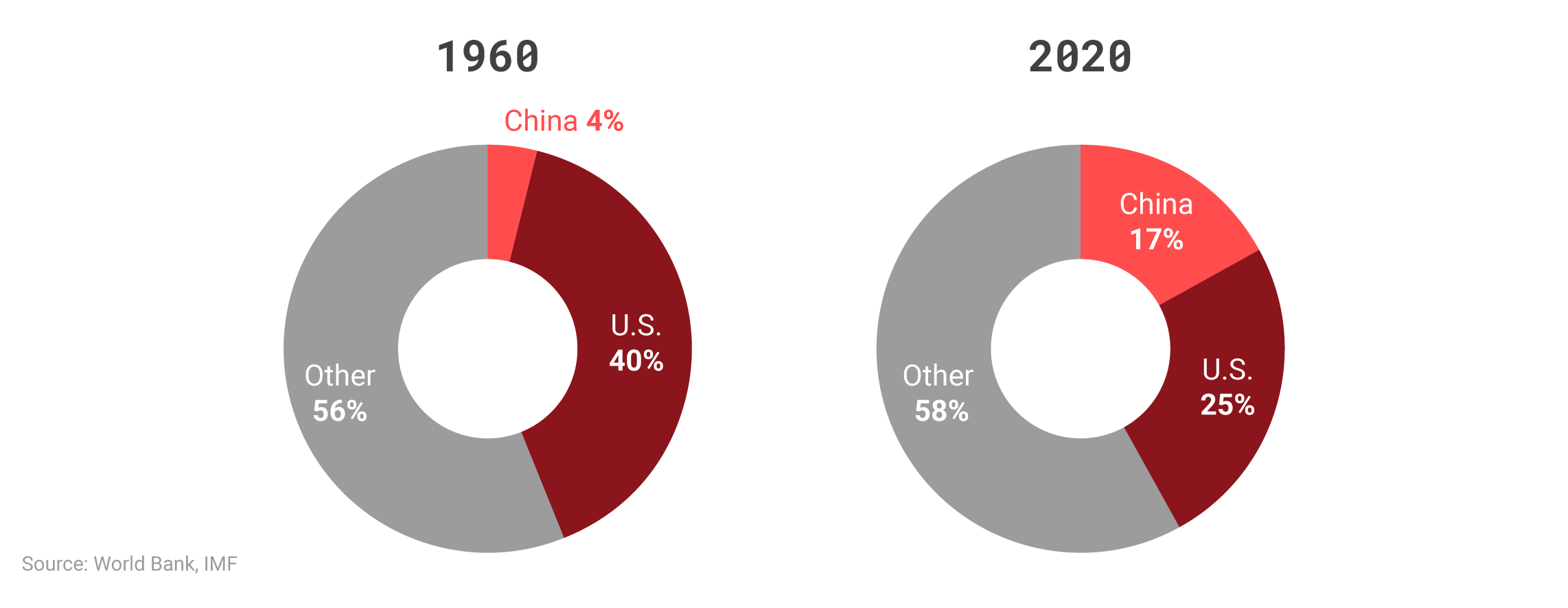

This means, for example, the United States need not accede to China’s assertions of a sphere of influence in the Western Pacific. There is no longer much doubt that China’s goal in that region is to exclude the United States military out to the so-called second island chain and to establish its economic and diplomatic preponderance over the region’s nations. Beyond Taiwan and the South China Sea, however, it is not clear that Beijing’s commitment to this vision exceeds the United States’ commitment to maintain its own preponderant position—nor does it have the military or other means to do so. Furthermore, there is every indication the region’s states are willing and able to both do business with China and resist Beijing’s efforts to assert its dominance.17Joshua Espena and Chelsea Bomping, “The Taiwan Frontier and the Chinese Dominance for the Second Island Chain,” Australian Institute of International Affairs: Australian Outlook, August 13, 2020, https://www.internationalaffairs.org.au/australianoutlook/taiwan-frontier-chinese-dominance-for-second-island-chain/.

Share of global GDP (MER)

The emergence of China as a global power means the return of multipolar great power competition. While China will look to establish a sphere of influence in the Western Pacific, countries in the region likely can and will balance against those efforts.

Even where these favorable conditions prevail, of course, any U.S. effort to thwart another state’s assertion of a sphere of influence necessarily carries with it the inevitability of friction and the possibility of armed conflict. The dynamics of misperception, miscalculation, and unintended escalation mean great power competition always entails the danger of war—perhaps nowhere more starkly than when one or both competitors fear that one of their core interests is at stake. Under the relatively favorable conditions described here, however, the probability that one power challenging another’s efforts to assert a sphere will lead to war is significantly lower than would otherwise be the case.

A differentiated approach to spheres of influence, of course, must also recognize that, where these favorable conditions do not exist, efforts to thwart another great power’s assertion of a sphere is likely to prove not only futile but positively dangerous. Simply put, in those cases where both the regional balance of power and the balance of commitment favors the asserting great power, and where states within the asserted sphere lack the power to resist, either the asserting power will be successful in imposing a sphere of influence or the attempt to thwart its assertion will lead to war.

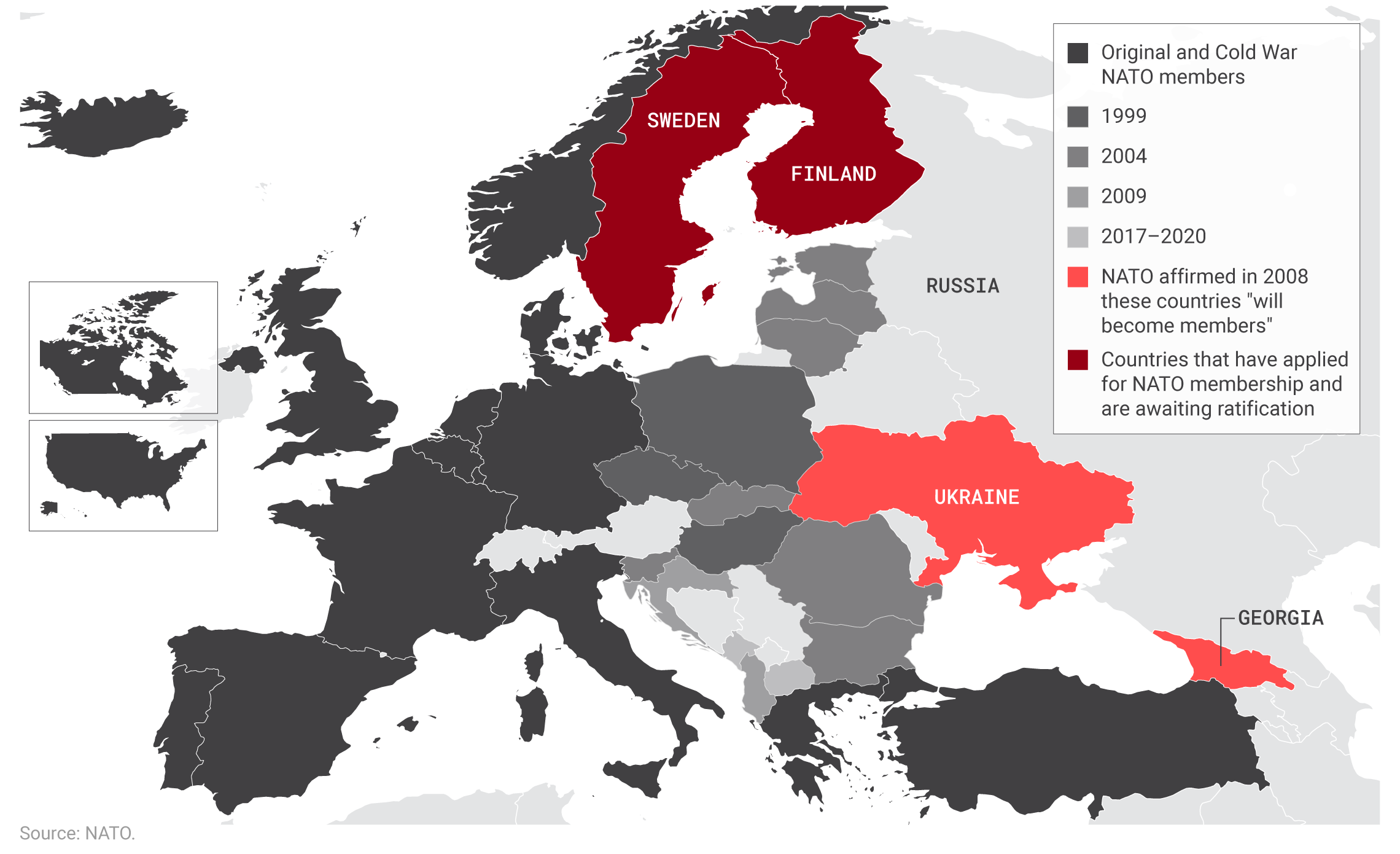

This is arguably what happened in the Russo-Ukrainian case in 2022: Moscow’s repeated efforts to signal that it would not tolerate Ukraine drifting into the West’s orbit (in the form of joining either NATO or the European Union) were ignored by Kyiv, Brussels, and Washington. Given both Russia’s deep commitment to excluding the West from extending its influence into Ukraine and its apparent military preponderance in the region, the prospect of Ukraine’s imminent break from Russia’s asserted sphere of influence resulted in war.18See Frederick Kliem, Russia, NATO, and Ukraine: The Return of Spheres of Influence (Singapore: RSIS, 2022); and Andrew A. Michta, “What Russia Wants From A Ukraine Crisis: A Sphere Of Influence In Eastern Europe,” 19FortyFive, December 13, 2021, https://www.19fortyfive.com/2021/12/what-russia-wants-from-a-ukraine-crisis-a-sphere-of-influence-in-eastern-europe.

The history of NATO expansion

Russian fears over NATO expansion into its perceived sphere of influence and Ukraine’s moves into the West’s orbit, while not the only factors, contributed significantly to Moscow’s decision to invade Ukraine.

In cases where conditions favor the asserting power, a differentiated approach to spheres of influence would therefore prescribe a more modest strategic approach: one that eschews resistance in favor of working to make the resulting spheres as stable and tolerable (both for the United States and the states within the sphere) as possible. Minimally, this would require working with the asserting power to establish unambiguous boundaries that are formally or informally recognized by all—including the subordinated states.

Endnotes

- 1Andrew Hurrell, “Sphere of Influence,” The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics, (3rd ed., 2009).

- 2Amitai Etzioni, “Spheres of Influence: A Reconceptualization,” The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs 39, no. 2 (Summer 2015): 117-132. See also Van Jackson, “Understanding Spheres of Influence in International Politics,” European Journal of International Security 5, no. 3 (October 2020): 255–273.

- 3Evan R. Sankey, “Reconsidering Spheres of Influence,” Survival 62, no. 2, (March 2020): 41.

- 4Susanna Hast, Spheres of Influence in International Relations (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2014), ch. 2.

- 5An example of this was the U.S. sphere asserted over the Western Hemisphere during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Following the declaration of the Monroe Doctrine in 1823, Washington worked to achieve military dominance throughout the Western Hemisphere, exclude extra-hemispheric powers from the region, subordinate the sphere’s lesser powers geopolitically and economically, and on occasion even to directly influence the internal politics of other the countries within the sphere.

- 6Evan N. Resnick, “What’s Missing in the Debate Over Spheres of Influence,” Chatham House, March 2020, https://americas.chathamhouse.org/article/whats-missing-in-the-debate-over-spheres-of-influence/.

- 7Paul Keal, Unspoken Rules and Superpower Dominance, (London: Macmillan, 1983).

- 8Lindsay O’Rourke and Joshua Shifrinson, “Squaring the Circle on Spheres of Influence: The Overlooked Benefits,” The Washington Quarterly 45, no. 2 (July 2022): 105–124.

- 9Condoleeza Rice, “Secretary Rice Addresses U.S.-Russia Relations at The German Marshall Fund,” U.S. Department of State, September 18, 2008, https://2001-2009.state.gov/secretary/rm/2008/09/109954.htm.

- 10Hal Brands and Charles Edel, “The Disharmony of the Spheres,” Commentary, January 2018, https://www.commentary.org/articles/hal-brands/the-disharmony-of-the-spheres/.

- 11Michael J. Mazzarr, Understanding Competition: Great Power Rivalry in a Changing International Order— Concepts and Theories, (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2022); Elbridge A. Colby and A. Wess Mitchell, “The Age of Great-Power Competition: How the Trump Administration Refashioned American Strategy,” Foreign Affairs, January/February 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/age-great-power-competition.

- 12The most prominent proponent of embracing a return of SOIs is Graham Allison, “The New Spheres of Influence.” Foreign Affairs, February 10, 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-02-10/new-spheres-influence.

- 13Sankey, “Reconsidering Spheres of Influence.”

- 14For a fuller discussion see O’Rourke and Shifrinson, “Squaring the Circle on Spheres of Influence: The Overlooked Benefits.”

- 15There are, of course, those who argue that the return of SOIs is neither inevitable nor desirable. See Steven Pifer, “Contending With—Not Accepting—Spheres of Influence,” Russia Matters, March 5, 2020, https://www.russiamatters.org/analysis/contending-not-accepting-spheres-influence; Robert Kagan, “The United States Must Resist A Return to Spheres of Interest in the International System,” Brookings February 19, 2015, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2015/02/19/the-united-states-must-resist-a-return-to-spheres-of-interest-in-the-international-system/; Hal Brands and Charles Edel, “The Disharmony of the Spheres,”; and, Hal Brands, “Don’t Let Great Powers Carve Up the World,” Foreign Affairs, April 20 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2020-04-20/dont-let-great-powers-carve-world.

- 16Brands, “Don’t Let Great Powers Carve Up the World.”

- 17Joshua Espena and Chelsea Bomping, “The Taiwan Frontier and the Chinese Dominance for the Second Island Chain,” Australian Institute of International Affairs: Australian Outlook, August 13, 2020, https://www.internationalaffairs.org.au/australianoutlook/taiwan-frontier-chinese-dominance-for-second-island-chain/.

- 18See Frederick Kliem, Russia, NATO, and Ukraine: The Return of Spheres of Influence (Singapore: RSIS, 2022); and Andrew A. Michta, “What Russia Wants From A Ukraine Crisis: A Sphere Of Influence In Eastern Europe,” 19FortyFive, December 13, 2021, https://www.19fortyfive.com/2021/12/what-russia-wants-from-a-ukraine-crisis-a-sphere-of-influence-in-eastern-europe.

The Latest

Featuring Dan Caldwell

November 5, 2025

Featuring Jennifer Kavanagh

November 5, 2025

November 4, 2025

November 4, 2025

Events on Grand strategy