The war between Israel and Hamas has increased the threat to U.S. troops in the Middle East, particularly to the 3,400 personnel in Iraq and Syria. But there is no good reason for U.S. forces to be there. The U.S. presence needlessly risks war by allowing Iran and militias it funds to threaten U.S. troops. ISIS’s capabilities have been degraded, capable local actors eagerly hunt the groups’ remnants, and the United States can still strike from a long distance if necessary. U.S. forces should be withdrawn from Iraq and Syria as part of a broader effort to deprioritize the Middle East and avoid an ill-advised conflict with Iran.

Understanding the Israel-Hamas war

The Israel-Hamas conflict shows little signs of slowing down, and the risk of a wider war remains credible. This brief examines and addresses the complex dynamics at play that could cause the crisis to expand, and it clearly defines parameters for how the U.S. should navigate the conflict. Washington should avoid direct U.S. military involvement, work with all parties to prevent escalation, and redeploy troops out of Syria—and eventually Iraq—which denies Iran leverage for broadening the war.

Phantom Empire: The illusionary nature of U.S. military power

U.S. bases and troops abroad no longer translate into influence, making America’s far-flung garrison a “Phantom Empire.” The refusal of U.S. leaders to countenance drawdowns in most cases removes what leverage U.S. troops might provide over host nations. U.S. commitments in Europe, the Middle East, and East Asia yield example after example of countries whose close defense relationship with the United States does not prevent them from going their own way geopolitically.

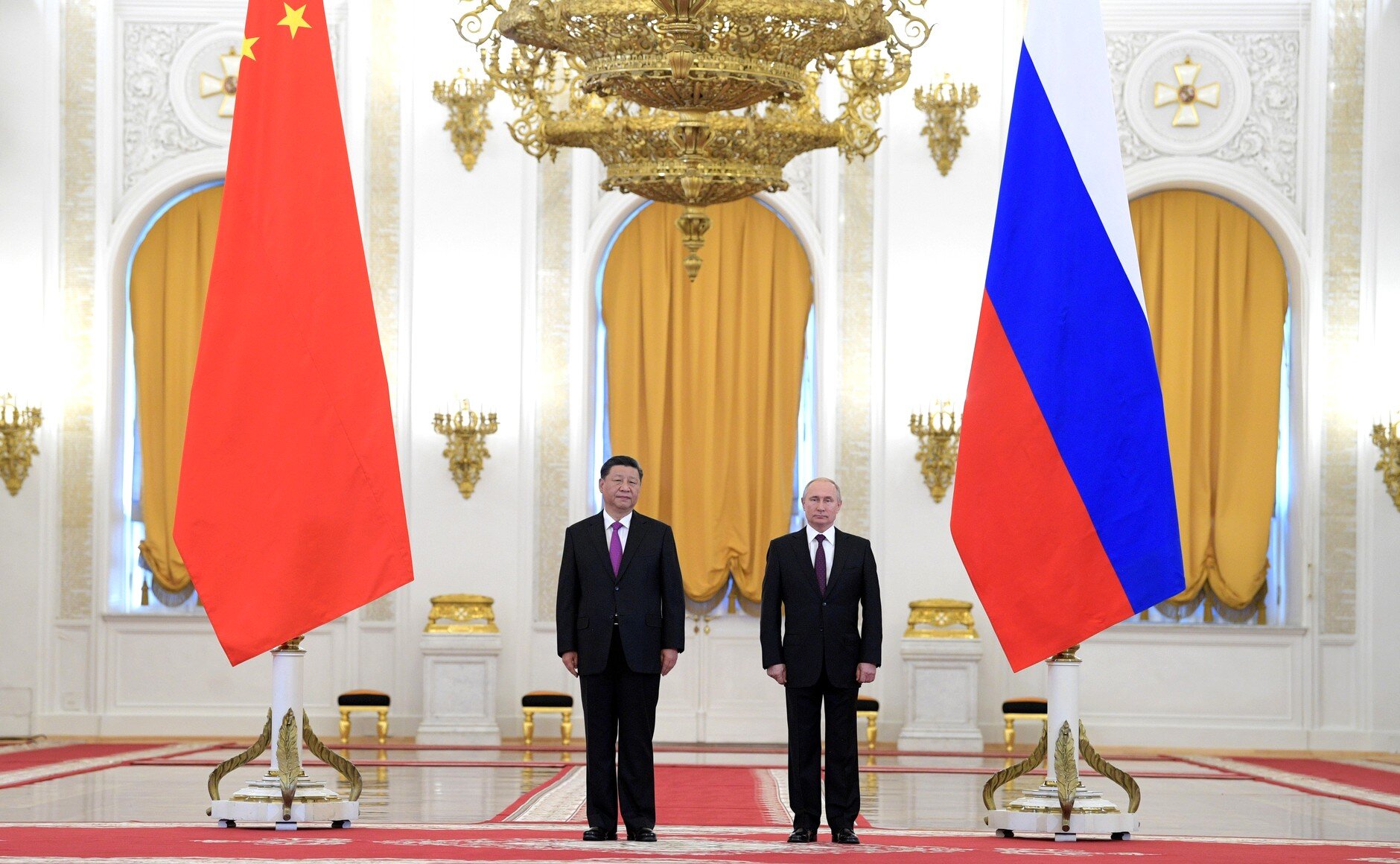

Perils of pushing Russia and China together

While much has changed since the Cold War, it remains in the U.S. interest to avoid Russia and China—the only two near-peer, nuclear-armed U.S. competitors—combining their economic and military power. The current U.S. approach of dual containment encourages their cooperation. Mounting a global campaign pitting democracies against autocracies adds to that pressure. The U.S. should focus on reducing tension with Moscow to improve the chances of productive diplomacy and limit incentive for Russia to cooperate with China against the U.S.

Global Posture Review 2021: An opportunity for realism and realignment

The Biden Administration’s forthcoming Global Posture Review—a top-to-bottom examination of all overseas U.S. military bases and deployments—should jumpstart a needed shift in U.S. strategic thinking away from the leftover assumptions of the Cold War and the War on Terror. Through balancing and burden sharing in Asia, major troop reductions in Europe and the Middle East, and limiting presence deployments to preserve military readiness, the United States can realign its military posture to sustainably confront the challenges ahead.

A plan for U.S. withdrawal from the Middle East

Over four years, the U.S. could reduce its presence in the Middle East by as many as 50,000 military personnel, mainly by drawing down its forces in four key states—Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, and the UAE—and ending regular deployments to the region by carrier battle groups. Moving to the region’s periphery—drawing on existing bases and access agreements with Jordan and Oman—could position the U.S. to return to a role as offshore balancer with an option to completely withdraw from the region.

The case for withdrawing from the Middle East

Nothing about the Middle East warrants an enduring U.S. military presence there. Of the few important interests there—preventing major terrorist attacks, stopping the emergence of a market-making oil hegemon, curbing nuclear proliferation, and ensuring no regional actor destroys Israel—not one requires a permanent garrison of American troops. The roughly 60,000 U.S. military personnel in the region should come home.

Considering the “zero option”

During the Cold War, the U.S. operated just two major bases in the Middle East. Today, even though the region is of vastly diminished strategic importance, the U.S. maintains an expansive network of bases. The “zero option”—reducing U.S. military bases in the region to zero—should be responsibly considered. It would force decision makers to rethink the means-end chain for securing U.S. interests. Employing other levers of power would free up resources—military and otherwise—and avoid costly entanglements in the region. Removing immediate U.S. military protection would also prompt partners to reconsider their own positions and conduct their external relations with greater circumspection.