Key points

- The strategic importance of the Middle East has declined, but Washington has so far inadequately adjusted. Diversification of energy sources and reduction in external threats to the region make the Middle East less important to U.S. interests.

- Permanent garrisons are not needed to protect those interests. Bases exist to serve specific operational and strategic needs; once those needs are met, they can be eliminated lest they become an unnecessary drain on resources or, worse, an outright liability. This is increasingly becoming the case with the U.S. Middle East force posture.

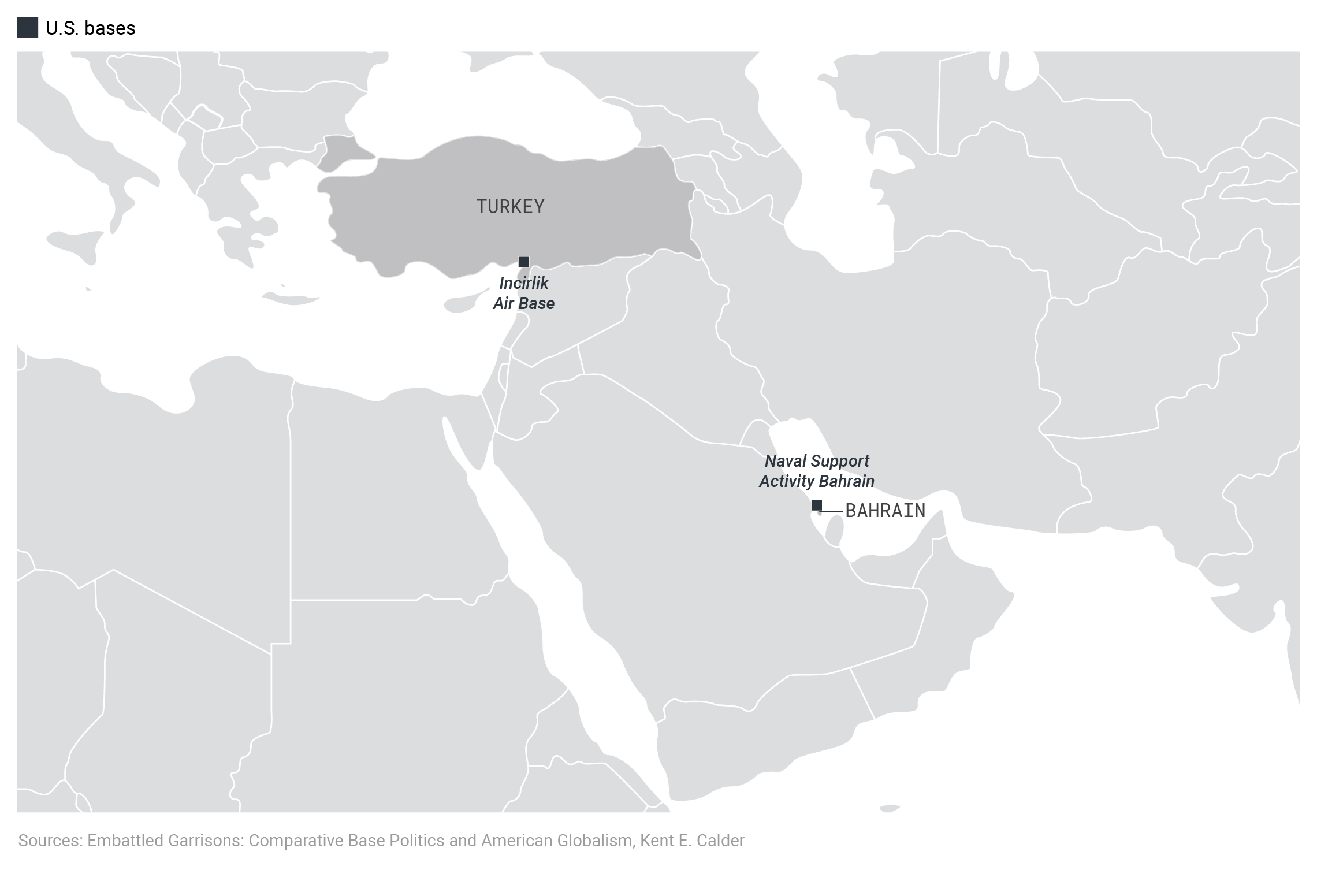

- During the Cold War, the U.S. used different levers of national power—including economic aid, military assistance, and covert action—to achieve its strategic objectives in the Middle East. Direct deployment of military force was rare and of finite duration, while permanent basing was limited to two locations (Bahrain and Turkey).

- The possibility of a “zero option”—full withdrawal of permanent U.S. bases—would force an examination of each facility in the region and mandate there be a specific reason for keeping it, as opposed to simply maintaining the status quo.

- The political and societal pressures exposed by the 2011 Arab Spring have not been addressed and are likely to spark additional unrest throughout the Middle East in the years ahead. There are compelling reasons for the U.S. to consider watching these changes from an offshore posture.

America’s Middle East treadmill

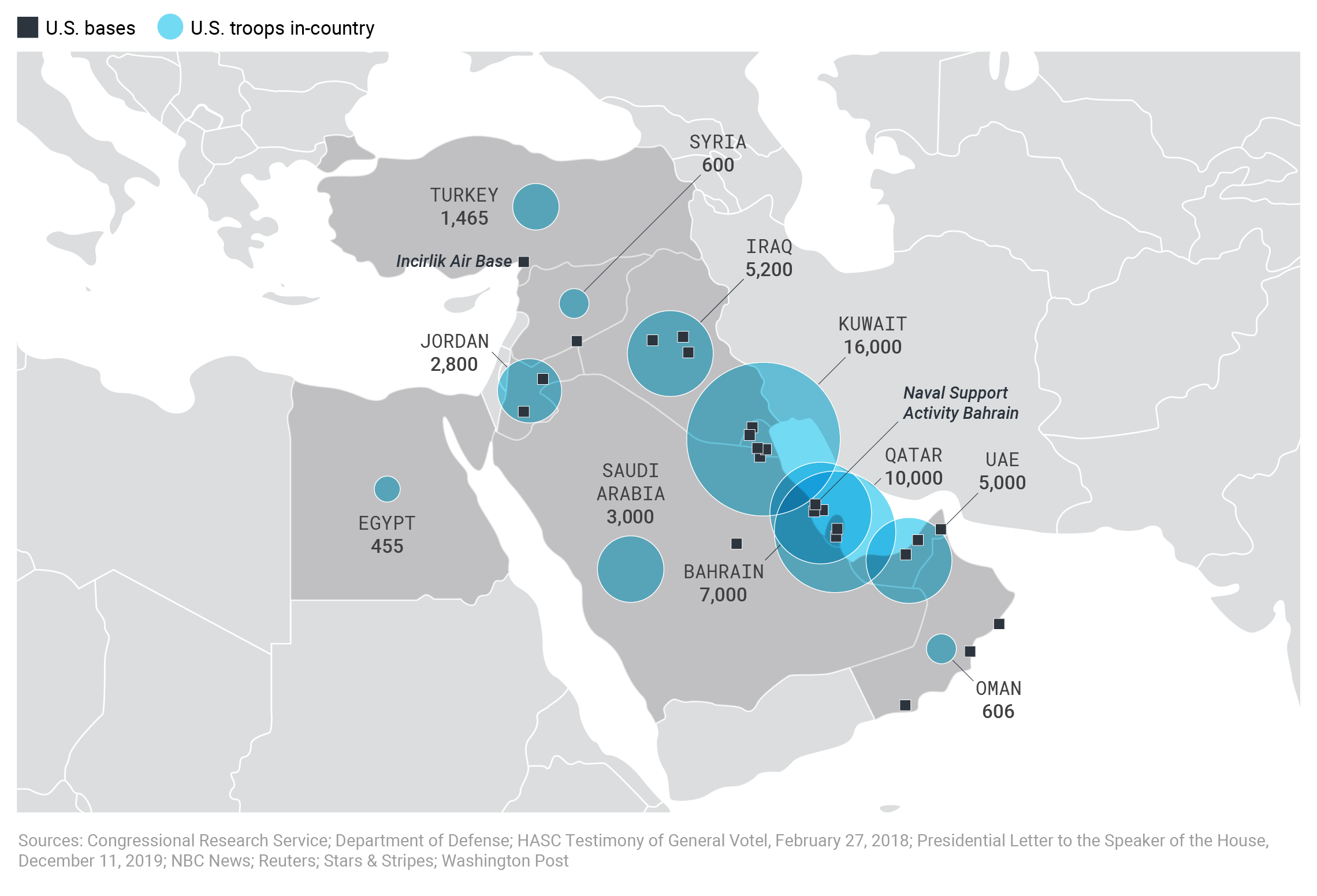

Recent events in Iraq—culminating in Iranian missile strikes against U.S. bases—have refocused attention on the question of the future of U.S. presence in that country. This is a necessary discussion, but is only one small part of the broader debate that should take place about the U.S. force posture in the Middle East.1For the purposes of this paper, the term “Middle East” largely reflects the area as it was defined in the early years of the Cold War with some minor modifications. In 1957, in response to a Congressional query, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles quoted Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs John N. Jernegan, who defined the region as “the area lying between and including Libya on the west and Pakistan on the east and Turkey on the north and the Arabian Peninsula to the south.” Dulles went on to append the Sudan and Ethiopia to Jernegan’s definition, but those states now more comfortably fit into AFRICOM’s area of responsibility and (along with Djibouti) are omitted from the boundaries of “the Middle East” used here, reverting instead to Jernegan’s unaltered definition. For Dulles’s comments, see U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, Subcommittee on Foreign Economic Policy of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, Amendment to the Anglo-French Financial Agreement: Hearings before the Subcommittee on Foreign Economic Policy of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, 85th Cong., 1st Sess., 1957, 354–355. Whereas the U.S. spent most of the Cold War with only two permanent bases—at Manama in Bahrain and Incirlik in Turkey—U.S. forces now operate from over a dozen major facilities, long after the end of the Iraq War and the nominal defeat of ISIS. U.S. forces in the Middle East have declined in total numbers from the high point of the Iraq War in 2008—when they numbered more than 200,000—but America still deploys an estimated 50,000 troops in the region.2Figures for 2008 force levels taken from: U.S. Library of Congress. Congressional Research Service, Troop Levels in the Afghan and Iraq Wars, FY2001–FY2012: Cost and Other Potential Issues, by Amy Belasco, R40682 (2009), 6. The 2019 estimate of 50,000 personnel deployed in the region was derived from a country-by-country assay building off various open-source documents. Country-specific force levels can be found in the chart accompanying this article. Sources consulted were: “Incirlik AB—Quick Overview,” Military Installations. Department of Defense, https://installations.militaryonesource.mil/military-installation/incirlik-ab; Alexa Liautaud, “How Many Troops Are Serving in America’s Legacy Wars? We Still Really Don’t Know,” NBC News, November 11, 2019, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/how-many-troops-are-serving-america-s-legacy-wars-we-n1079531; John Vandiver, “U.S. Troops Deployed to Israel Get a New Barracks,” Stars & Stripes, September 19, 2017, https://www.stripes.com/news/us-troops-deployed-to-israel-get-a-new-barracks-1.488440; Phil Stewart, “Exclusive: U.S. Military Completes Pullback from Northeast Syria, Esper Says,” Reuters, December 5, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-usa-syria-exclusive/exclusive-us-military-completes-pullback-from-northeast-syria-esper-says-idUSKBN1Y90CU; “Text of a Letter from the President to the Speaker of the House of Representatives and the President Pro Tempore of the Senate,” The White House, December 11, 2019, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/text-letter-president-speaker-house-representatives-president-pro-tempore-senate-8/; U.S. Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, Bahrain: Unrest, Security, and U.S. Policy, 95-1013 (2019), 2; U.S. Library of Congress. Congressional Research Service. Kuwait: Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy, RS21513 (2019), 7-8; U.S. Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, The United Arab Emirates: Issues for U.S. Policy, RS21513 (2019), 18; and Joseph Votel, “The Posture of U.S. Central Command. Terrorism and Iran: Challenges in the Middle East,” House Armed Services Committee, February 27, 2018, 31, https://docs.house.gov/meetings/AS/AS00/20180227/106870/HHRG-115-AS00-Wstate-VotelJ-20180227.pdf. For every “withdrawal” of forces from one area, there is seemingly a redeployment or consolidation of manpower and equipment in another.3A sentiment perfectly captured in the headline of this story on the U.S. “withdrawal” from Syria in October 2019: Eric Schmitt and Helene Cooper, “Hundreds of US Troops Leaving, Also Arriving, in Syria.” New York Times, October 30, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/30/world/middleeast/us-troops-syria-trump.html.

American force deployments not only cost actual money, but also come with increased risk of embroiling the U.S. in conflicts it can no longer afford. As matters stand, American bases in the region already enable a number of dubious commitments, including ambiguous residual missions in Iraq and Syria and baffling support to the Saudi-UAE war effort in Yemen. These facilities also embody a more fundamental question for U.S. foreign policy: How long should America continue its military partnerships with both secular dictatorships (such as Egypt) and the antiquated monarchies of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC)?

In a perfect world, debate would produce a clear U.S. strategy in the Middle East and a plan for genuinely reducing the U.S. presence would be derived in support of it. But the policy community—both inside and outside government—has been slow to embrace major change in the U.S. approach to the region, despite increased recognition that at some point, America should scale back its involvement. Occasionally, an article like “America’s Middle East Purgatory” by Mara Karlin and Tamara Wittes in Foreign Affairs sparks intermittent Beltway debate on this subject, but serious discussions about changes to the U.S. basing architecture are lacking.4Mara E. Karlin and Tamara Cofman Wittes, “America’s Middle East Purgatory,” Foreign Affairs 98, no. 1 (2020): 88–100.

Thus, instead of posture following strategy, it might be necessary to argue for reduced presence first, as a means of forcing the debate on what U.S. goals and intentions in the region should be. One advantage to culling bases is it requires those who wish to keep them to enunciate a specific reason for doing so, rather than just relying on the status quo. It may well be that America should maintain one or more facilities in the Middle East—though a so-called “zero option” should also be on the table—but a good rationale, rather than simply strategic inertia, should keep them there.

During the Cold War, the U.S. pursued hegemony in the Middle East for the sake of ensuring access for itself and its allies to the region’s essential energy supplies (or, more accurately, to deny others the ability to claim dominance over said resources). As will be discussed below, the pursuit of that goal took many forms, only one of which was the deployment of (extremely limited) military forces in the region. The main lesson is the U.S. could achieve its objectives without the extensive basing infrastructure it currently possesses.

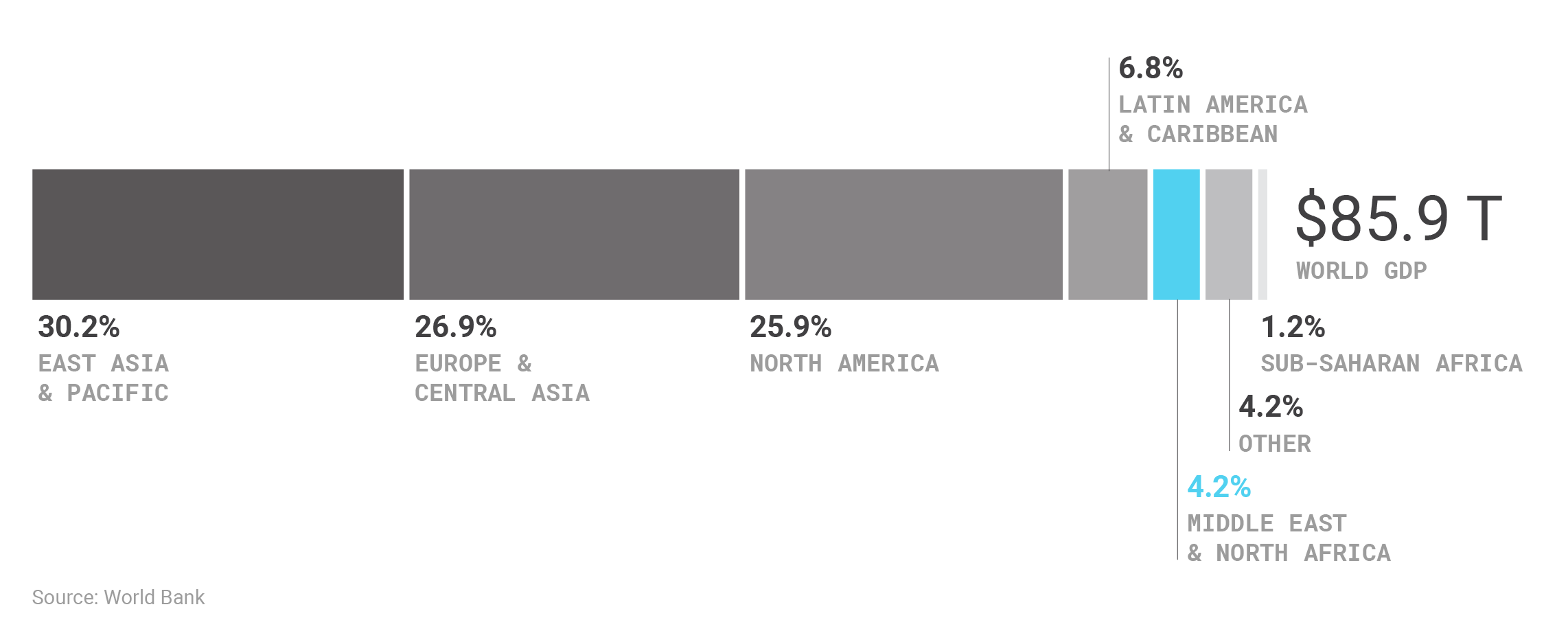

World GDP by region

The Middle East is a region of diminishing strategic importance. Its economic activity is dwarfed by the U.S., Europe, and Asia, the hubs of the world economy.

But it is also necessary to recognize the overall objective of strategic supremacy in the Middle East is no longer valid. Changes to the regional and global security settings, as well as diversification of energy supplies, mean the region is less important to U.S. interests than it once was. For context, the Middle East and North Africa account for 4.2 percent of global GDP.5For 2018, the Middle East and North Africa collective GDP was $3.611 trillion of the $89.91 trillion total global GDP. See “GDP (Current US$) – Middle East & North Africa,” The World Bank, accessed January 30, 2020, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=ZQ; and “GDP (current US$),” The World Bank, accessed January 30, 2020, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD. Washington has been slow to accept this shift. Yet this diminution in the Middle East’s strategic status should be front and center as debate ensues about the future of America’s basing network in the region. Since the Middle East is of decreasing importance, is it worth expending the current level of resources there while contending military demands exist elsewhere, especially in East Asia, and while rising national debt and other domestic priorities compete for resources?

America offshore—the Cold War posture

Even before the end of the Second World War, the U.S. considered future access to the Middle East’s oil resources to be a national priority. America then accounted for two-thirds of all the world’s petroleum production, but Washington recognized access to the Middle East’s energy supplies would be essential to the economic recovery of European and Asian states—a prerequisite for keeping those nations inoculated against communist influences.6Anand Toprani, “Oil and the Future of U.S. Strategy in the Persian Gulf,” War on the Rocks, May 15, 2019, https://warontherocks.com/2019/05/oil-and-the-future-of-u-s-strategy-in-the-persian-gulf/. America’s second, intertwined goal—which became even more apparent as the Cold War intensified and entered the 1950s—was to prevent the Soviet Union from attaining dominance over the region. That led to the Eisenhower Doctrine, which spelled out American willingness to support any country in the Middle East seeking to combat threats from communist forces.7Dwight D. Eisenhower, Special Message to Congress (Eisenhower Doctrine), (speech, Washington, DC, January 5, 1957), Miller Center at University of Virginia, https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches/january-5-1957-eisenhower-doctrine.

U.S. military bases in the Middle East during the Cold War

During the Cold War, when the Middle East’s geostrategic importance was vastly greater, the U.S. only operated two major military bases. Incirlik in Turkey was more about Europe’s security to the North, while Bahrain supported minimal naval vessels for offshore operations.

Significantly, America pursued its strategic goals with almost no military facilities in the region. It did use a number of other levers of power—including economic aid, military sales and equipment transfers, business investments, and covert operations—with varying success. Questions can be raised about the viability and morality of some of these measures. The U.S. (and Great Britain) often entered business partnerships with the region’s sovereigns, allowing for the export of oil at extremely favorable prices but to the detriment of the everyday citizens of Middle Eastern states. Covert operations yielded questionable results, and in the particular case of Operation AJAX—the overthrow of Iran’s democratically-elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh—continue to contribute to poor relations between Washington and Tehran to this day.

The argument here isn’t that the U.S. always acted benignly during this period, but rather that military deployments and permanent bases were not the default solution. The point is worth emphasizing: At a time of extreme international uncertainty, with an essential geopolitical objective at play, the U.S. was willing to use non-military means to pursue its objectives and largely succeeded in realizing them—keeping the Middle East free of Soviet influence (dalliances by Nasserist Egypt and others notwithstanding) while ensuring oil flowed to its recovering allies in East Asia and Europe.

Yes, America did occasionally resort to direct use of force—as in 1958, when it sent Marine and Army units to shore up the pro-U.S. government in Lebanon. But there, too, a significant difference is worth underscoring: The troops didn’t stay for a decades-long deployment; instead, they withdrew within four months after the situation stabilized.

To the extent the U.S. kept bases in the broader Middle East and North Africa, they were primarily focused not on energy security, but rather on strategic missions related to the struggle against Soviet communism. This was the case with Kabkan, Iran (a remote electronic listening site for observing Soviet rocket tests); Peshawar, Pakistan (a secret base for U2 surveillance flights); and a series of small bases in Morocco that supported Strategic Air Command.8For more on Kabkan, see Hedrick Smith, “Ex‐CIA. Aide Tells of Life at Iran Listening Post,” New York Times, March 3, 1979, https://www.nytimes.com/1979/03/03/archives/excia-aide-tells-of-life-at-iran-listening-post-catandmouse-game.html. On the U2 base at Peshawar, see “Airgram A–550 From the Embassy in Pakistan to the Department of State, October 6, 1969,” Foreign Relations of the U.S., 1969–1976, Volume E–7, Documents on South Asia, 1969–1972, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76ve07/d38. On U.S. bases in Morocco during the 1950s, see “Memorandum from the Acting Assistant Secretary of State for European Affairs (Elbrick) to the Secretary of State, May 31, 1956,” Foreign Relations of the U.S., 1955–1957, Africa, Volume XVIII, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1955-57v18/d193. Even the longest-standing U.S. military facility in the Middle East, the air base at Incirlik, Turkey, was focused “northward” to counter the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact, rather than “southward” toward the Gulf and energy security. It wouldn’t be until 1990 at the Cold War’s end that Incirlik would become a true “Middle Eastern hub” for the U.S., when Turkey granted special permission for U.S. forces to use the facility in support of Operation Desert Shield/Desert Storm following Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait.

Within the Persian Gulf, the U.S. briefly had only one base, an expanded airfield at Dhahran, Saudi Arabia. But the Saudi leadership was wary of foreign deployments on its territory and chose not to renew the lease on the facility; U.S. forces only operated from the base up until 1962.9Bruce Riedel, Kings and Presidents: Saudi Arabia and the U.S. since FDR (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2018), 35. In addition, U.S. naval forces did have access to HMS Jufair, the British Royal Navy’s base in Manama, Bahrain, and would take over the U.K. position when it formally withdrew from the region in 1971. But for the duration of the Cold War, the number of American ships stationed at Manama could usually be counted on one hand.10F. Gregory Gause, The International Relations of the Persian Gulf (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 22.

With this sparse architecture, America achieved its two main strategic objectives of ensuring oil flow and thwarting Soviet ambitions in the region. While some might argue that the U.S. was able to do so in part because Great Britain operated its own basing network in the Middle East until 1971 and essentially served as “regional sheriff” in America’s stead, this point too requires elucidation.

First, British basing was itself fairly sparse, especially after the late 1950s when British forces were forced out of Egypt (1956) and then Iraq (1959). From that point on, aside from HMS Jufair in Bahrain, deployments were largely confined to the region’s periphery, with the main U.K. bases being offshore in Cyprus and at the southern tip of the Arabian Peninsula in Aden.11For more on the devolution of the British military posture in the Middle East from the end of the Second World War through the 1950s, see Karol R. Sorby, “Great Powers and the Middle East after World War II (1945-1955),” Asian and African Studies 10, no. 1 (2001): 65–70.

Moreover, the British only employed force once in defense of energy interests in the Gulf during this time, deploying commandos and an RAF squadron to reinforce Kuwait when Iraqi strongman Adb al-Karim Qasim appeared to threaten the emirate in 1961. The forces involved deployed from outside the region and—as in the case of U.S. forces in Lebanon—promptly withdrew when the threat alleviated.12Riedel, Kings and Presidents, 35.

Finally, even if one were to allow that British forces and influence were decisive in achieving American aims, that in itself is a lesson: the U.S. shouldn’t have to do it all by itself. If nations other than the U.S. can exert stabilizing influence in the Middle East, that should be welcomed.

Significantly, when the British withdrew from the region in 1971, America didn’t rush to replace the minimal U.K. basing architecture with its own. With the sole exception of Manama, where the U.S. Navy supplanted HMS Jufair with its own limited facility and token deployment of ships, America would maintain no other bases in the Middle East for the next 20 years, save for Incirlik in Turkey, which, again, was used exclusively for NATO operations related to Europe’s defense.

Despite the absence of major bases, America was still able to employ military assets decisively in major operations when needed. For example, it provided Israel with critical resupply during the Yom Kippur War (Operation Nickel Grass), using only the Azores in the North Atlantic and assets based in the continental U.S.13John T. Correll, “The Yom Kippur Airlift,” Air Force Magazine, June 24, 2016, https://www.airforcemag.com/article/the-yom-kippur-airlift/. The U.S. was also able to fight the so-called “tanker war” against Iran (Operation Earnest Will) with only tangential support from ashore bases (mainly in the form of AWACS flights), while also using the novel “sea basing” approach that saw special operations forces deployed on two barges tethered in the Persian Gulf.14David B. Crist, “Joint Special Operations in Support of Operation Earnest Will,” Joint Force Quarterly, Autumn-Winter (2001-02): 15–22.

Of course, it can be argued that each of these operations might have benefitted from access to additional facilities in the region, but they were ultimately not needed. Given the costs that such bases can incur—and not merely in monetary terms—this is an essential point to consider, as America reassesses the future of its footprint in the Middle East. Just because the U.S. can have a base, doesn’t mean that it should, especially if offshore options can meet the same demand.

More is less—the current U.S. footprint

The minimalist basing architecture of the Cold War stands in stark contrast to current U.S. deployments. Foremost, the U.S. maintains 5,000 combat troops in Iraq—and nearly another 5,000 troops are reportedly being deployed to the region to reinforce them in the wake of the unrest sparked by U.S. airstrikes against Iranian-back militias.15750 troops from the 82nd Airborne were en route to the region at the time of writing, with an additional 4,000 expected to follow in the coming weeks. It’s unclear if all of those forces will be deployed immediately in Iraq, or if, instead, they will be on “standby” in Kuwait. See Shawn Snow, Howard Altman, and Philip Athey, “750 Soldiers with 82nd Airborne Headed for CENTCOM, Additional 4,000 Troops Expected to Deploy as Iran Tensions Mount,” Military Times, December 31, 2019, https://www.militarytimes.com/flashpoints/2020/01/01/750-soldiers-with-82nd-airborne-headed-for-centcom-additional-4000-troops-expected-to-deploy-as-iran-tensions-mount/. Six hundred troops also remain in Syria despite the “withdrawal” hastily begun in October 2019.16Stewart, “Exclusive: U.S. Military Completes Pullback from Northeast Syria, Esper Says.” In addition, America deploys a “small undisclosed number” of special operations forces in Yemen.17“Text of a Letter,” The White House. The U.S. operates air bases at Shaykh Isa Air Base in Bahrain, Al-Udeid in Qatar, Azraq in Jordan, and Al Dhafra in the United Arab Emirates, while still maintaining forces at Incirlik in Turkey.

Over the past year, U.S. forces have also returned to Prince Sultan Air Base in Saudi Arabia, where 3,000 American military personnel are now stationed.18“Text of a Letter,” The White House. As well, America has no less than five major military facilities in Kuwait, mostly in support of Air Force and Army deployments, altogether totaling 16,000 personnel.19U.S. Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, Kuwait: Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy, RS21513 (2019), 7–8. Construction is currently underway on a massive, new air logistical hub in Kuwait, scheduled to be completed in 2023, even as $60 million is being invested in “Cargo City,” an interim air hub just outside Kuwait City.20Ramadan Al. Sherbini, “Key U.S. Military Air Hub to Open in Kuwait,” Gulf News, July 13, 2018, https://gulfnews.com/world/gulf/kuwait/key-us-military-air-hub-to-open-in-kuwait-1.2250807. An agreement was also signed with Oman in 2019, affording U.S. ships access to the ports of Duqm and Salalah, providing the U.S. Navy with additional options beyond Bahrain.21Sarah McFarlane, Summer Said, and Michael Amon. “Oil-Rich Saudi Arabia Barrels into the Gas Business,” Wall Street Journal, May 22, 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/oil-rich-saudi-arabia-barrels-into-the-gas-business-11558549343.

Finally, the U.S. has dozens of personnel in Israel to support ballistic missile defense,22Vandiver, “U.S. Troops Deployed to Israel Get a New Barracks.” deploys 60 troops in Lebanon to support anti-terrorism training, and maintains 455 troops in Egypt as part of the long-term peacekeeping force in the Sinai.23“Text of a Letter,” The White House.

In short, it is now arguably easier to name the countries in the Middle East where the U.S. does not base forces than where it does.

U.S. military bases in the Middle East today

While the Middle East is of diminishing strategic importance, accounting for just 4.2 percent of global GDP, the U.S. military currently operates an expansive basing presence that dwarfs its Cold War posture.

There is also the question of scale. Contrast the austere, often remote bases of the Cold War era with the sprawling facilities of today. The “temporary” Cargo City facility in Kuwait is 33,000 square meters and its replacement, West Al Mubarak, will be no doubt be even larger.24Sherbini, “Key U.S. Military Air Hub to Open in Kuwait.” Or simply look at the changes in Manama over the years. The U.S. base there has quintupled in size—going from 10 acres to 62—since the 1991 Gulf War and was designated as the headquarters for the reactivated Fifth Fleet in 1995.25“Manama [Juffair], Bahrain [Al Manamah] 26°14’10’N 50°34’59’E,” Global Security, accessed January 30, 2020, https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/facility/manama.htm. Instead of a handful of ships, the Fifth Fleet routinely hosts deployments by Amphibious Ready Groups and Carrier Battlegroups. Seven thousand sailors and Marines are now permanently stationed in Bahrain.26U.S. Library of Congress, Bahrain: Unrest, Security, and U.S. Policy.

The reader could fairly ask here if the scope and scale of U.S. bases really should be the issue. If this network—exhaustive though it might be—meets U.S. security interests, doesn’t that inherently make it worth its cost? Unfortunately, to answer in the affirmative requires indulging in a number of mistaken assumptions. The first of these is that a massive military presence is necessary for successful energy flow out of the region. As seen in the above examples from the Cold War, that is clearly not true. Moreover, in the case of major instances where oil shipments were impeded, military force or presence wouldn’t always have been of use in reversing the situation.

Consider the oil crisis of 1978–79. Production was impeded not by an external threat, but rather by internal developments in Iraq and Iran: the Khomeini revolution in the latter and the rise of Saddam Hussein in the former.27See Joshua Rovner and Caitlin Talmadge, “Hegemony, Force Posture, and the Provision of Public Goods: The Once and Future Role of Outside Powers in Securing Persian Gulf Oil,” Security Studies 23 (2014): 559, 566–567. Short of invading, occupying, and governing either state in perpetuity—actions which almost certainly would’ve bankrupted America—the presence of multiple regional bases or large standing forces would’ve had zero impact on the situations in either Iraq or Iran—and on the ensuing oil shortage.

This plays into a second misnomer: that the Middle East’s importance as an energy source for the U.S. and most of its allies has remained unchanged from 50 years ago. In fact, advances in the U.S. own domestic production—coupled with Europe’s admittedly questionable turn toward dependence on energy supplies from Russia—has rendered the Persian Gulf less an essential source than an important one.28Consider that the U.S. accounted for 18% of total oil production in 2018, compared to 12% for Saudi Arabia, while Russia produced 11%. See “What Countries Are the Top Producers and Consumers of Oil?” U.S. Energy Information Administration, November 6, 2019, https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=709&t=6. While what happens in the Gulf is still significant for overall global pricing, and the region does remain a vital supply source for East Asian allies like Japan, the Middle East is no longer as pivotal to America and NATO as it once was. This does not render the region “unimportant,” but it does again call for a serious reassessment of what resources the U.S. should realistically devote to it in the face of other demands elsewhere in the world and at home.

A third misconception is the U.S. requires a large network of standing bases to act militarily in the Middle East. As the examples cited above of Earnest Will and Nickel Grass both illustrate, this is not the case. Moreover, crises requiring the use of military force often create their own basing opportunities. For example, prior to 1990, the U.S. had not had a formal base in Saudi Arabia since the expiration of the lease on Dhahran in 1962. Yet once Saddam’s Iraq invaded Kuwait, the Saudi king quickly decided to accommodate a massive influx of forces from America and other Western nations.29Riedel, Kings and Presidents, 103–106. Fear can be a powerful motivator.

It is also worth considering that troops can return to a region after leaving. In a true worst-case scenario, nothing precludes the U.S. from reintroducing forces into the Middle East, should it eventually drawdown its significant commitment of personnel and facilities. Such a return conceivably could be needed in the event Iran were to pose a viable military threat to the oil and gas fields of the Arabian Peninsula. But here, too, perspective is needed: While Iran might use asymmetric assets—like its extensive network of militia proxies—to foster instability throughout the region, Iran is far from capable of conventionally invading, let alone occupying, the territory of the GCC.30Anthony H. Cordesman and Abdullah Toukan, “Iran and the Gulf Military Balance (Working Draft),” Center for Strategic and International Studies, October 3, 2016, https://csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/161004_Iran_Gulf_Military_Balance.pdf.

Both the Iranians and the Arab states they would face off against have numerous military shortcomings, but, on balance, the GCC countries do have superior, modern weaponry, while the backbone of Iran’s force structure remains platforms often acquired during the Shah-era, including M60 tanks and F-4 fighters—far removed from cutting edge.31Cordesman and Toukan, “Iran and the Gulf” 24, 36–38. Most experts agree Iran’s ability to conduct large-scale maneuver warfare over long distances is extremely limited.32Cordesman and Toukan, “Iran and the Gulf,” 79. So, too, is Iran’s economic capacity to fund an extended occupation of the GCC, even if it were somehow able to pull off a successful invasion.33On the state of the Iranian economy, see Keith Johnson, “Iran’s Ecoomy Is Crumbling but Collapse Is a Long Way Off,” Foreign Policy, February 13, 2019, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/02/13/irans-economy-is-crumbling-but-collapse-is-a-long-way-off-jcpoa-waivers-sanctions/.

A final factor works against an Iranian invasion scenario: geography. Attacking into the oil and gas fields of the Arabian Peninsula would require Iran to transit Iraqi territory, a move that is likely to be met with resistance by all Iraqis, even those Shiites who might otherwise feel some fraternity for Iranians. Such a violation would no doubt raise memories of the long and painful Iran-Iraq War of the 1980s and further engender anti-Iranian sentiment, a trend that had been on the rise prior to the recent spate of U.S. military strikes in Iraq.34Michael Young, “How Deep Is Anti-Iranian Sentiment in Iraq?” Carnegie Middle East Center, November 14, 2019, https://carnegie-mec.org/diwan/80313. While U.S.-Iran relations will remain complex, a land warfare threat by Tehran to the GCC is therefore a false specter, one that doesn’t require a large U.S. basing network to counter.

Bases are means to an end, not ends in themselves

Overseas bases occupy a strange place in popular and political discourse. Too often they are treated as a national “prize” whose loss is to be lamented. Consider the bizarre furor that erupted when Russian forces moved into the former airbase U.S. forces operated from in Manbij, Syria. The underlying implication in much of the media coverage was that Russia had somehow “won” something from America, simply by occupying an abandoned airfield.35As an example, see Ben Hubbard, Anton Troianovski, Carlotta Gall, and Patrick Kingsley, “In Syria, Russia Is Pleased to Fill an American Void,” New York Times, October 15, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/15/world/middleeast/kurds-syria-turkey.html.

Bases are simply tools, not an extension of national prestige or some form of war spoil. Bases exist to serve operational and strategic needs; once those needs are met, they can be dispensed with lest they become an unnecessary drain on resources or, worse, an outright liability. Given overall trends in the Middle East, it is worth considering that most of America’s bases in the region will soon fall into the latter category, assuming they have not already.

As stated at the beginning of this paper, U.S. bases carry costs that go beyond the financial. They also align U.S. interests with those of questionable regimes and risk entangling America in wars it would be better to avoid. U.S. support to the Saudi-UAE war in Yemen is the obvious example here, a campaign that has displaced an estimated 570,000 Yemenis and brought many parts of that country to the brink of famine.36Declan Walsh, “The Tragedy of Saudi Arabia’s War,” New York Times, October 26, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/10/26/world/middleeast/saudi-arabia-war-yemen.html. To date, American complicity in that war has only cost it morally. But the longer America remains in the Middle East—at least at the current inflated levels of presence—the more risks it runs of either becoming entangled in another costly war or finding itself targeted by additional non-state actors.

This is especially true as more turbulence is coming to the region. The Middle East’s authoritarian leaders have largely avoided implementing real changes in response to the events of the 2011 Arab Spring. Most have relied on a combination of increased repression and minor concessions that do not address the root causes of those demonstrations. Yet the social dissatisfaction and economic concerns that undergirded the 2011 protests have not gone away. And, as Marwan Muasher has argued, the long-term ability of regional states to placate their populations through “bribes” funded by oil exports has dissipated as petroleum prices remain suppressed.37Marwan Muasher, “The Next Arab Uprising,” Foreign Affairs 97, no. 6 (2018): 113–24. As the “rentier model” breaks down, regional states will be increasingly susceptible to domestic unrest. Many of the U.S.’s “hosts” are among the most vulnerable to instability long term, perhaps none more so than Bahrain.38See Richard McDaniel, “No ‘Plan B’: U.S. Strategic Access in the Middle East and the Question of Bahrain,” Policy Paper, Brookings Institution, 2013, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/24-us-strategic-access-middle-east-bahrain-mcdaniel.pdf.

The Arab Spring may prove to be a tremor, presaging a more significant seismic event. It can reasonably be asked how long autocratic regimes operating (at best) like eighteenth-century monarchies can continue in the twenty-first century. Eventually change will come to the Middle East, and its agents may not look kindly on an America that sided with repressive regimes for over three-quarters of a century. Amidst prosaic debates about the future of U.S. presence in the region, it is also worth considering: What if we simply get kicked out?

This, in turn, raises another paradox about America’s Middle East force posture. Since the invasion of Iraq in 2003, U.S. military presence there increasingly has been focused on counter-insurgency operations—that is, on fighting internal, rather than external threats to the region’s states. But American troop deployments, dating back to before the 9/11 attacks, are themselves a focus for groups opposed to the region’s current regimes, as well as a propaganda tool employed in recruiting young jihadists. It is thus possible to define the rationale for many of America’s bases in the Middle East as fighting the insurgencies that U.S. military presence helped contribute to in the first place. That is, of course, something of an over-simplification of the complex issue of radicalization among youths in Middle Eastern societies, but it cuts to the basic question about the purpose and utility of an ongoing, large U.S. military footprint in the region. Are we abetting the problem we’re allegedly fighting?39This is even more so the case when one factors in the overall questionable record of defeating jihadist elements through force alone over the long term. See, for example, the conclusions of the congressionally mandated study undertaken by the Center for Naval Analyses: Julia McQuaid, Jonathan Schroden, Pamela G. Faber, P. Kathleen Hammerberg, Alexander Powell, Zack Gold, David Knoll, and William Rosenau, Independent Assessment of U.S. Government Efforts against Al-Qaeda (Arlington, VA: Center for Naval Analyses, 2017).

Considering the “zero option”

This returns us to the question of a plan for the future of U.S. force posture in the Middle East. Writing in Defense One in 2018, analysts Melissa Dalton and Mara Karlin proposed a series of gradual measures to alter U.S. presence in the Middle East, including converting some of its active (or “hot”) bases to “warm” sites that could be reactivated as contingencies arise.40Melissa G. Dalton and Mara E. Karlin, “Toward A Smaller, Smarter Force Posture in the Middle East.” Defense One, August 26, 2018, https://www.defenseone.com/ideas/2018/08/toward-smaller-smarter-force-posture-middle-east/150817/. It’s a prudent starting point that includes the useful step of suggesting the Department of Defense undertake classified and unclassified reviews of its presence in the region with an eye to where it can be responsibly reduced. However, Dalton and Karlin stop short of arguing that the U.S. should leave the Middle East completely.

Yet full military withdrawal should be given responsible consideration when assessing U.S. defense planning over the next 10 to 15 years. Feeding incremental steps into a bureaucracy as large as the Department of Defense can have the effect of diluting them to the point of negation. Keeping the “zero option” on the table would force a more fulsome reassessment of each U.S. facility in the region, hopefully—as stated at the start of this paper—while also igniting a more honest discussion of broader U.S. strategy and interests in the region.

For many in Washington, the notion of completely withdrawing U.S. forces from the Middle East seems blasphemous, as the region’s importance has been a central strategic tenet for more than 70 years. But the question deserves to be asked: Could the U.S. remove all of its military presence from the Middle East? Certainly, not in the next year or two, but looked at in the context of the next decade and a half, might it be feasible—and even prudent? The answer could well be “no,” but the question should legitimately be posed as part of any useful debate on the future of U.S. strategy in the Middle East and the posture that would support it.

As the discussion of the U.S. approach to the Middle East during the Cold War illustrates, “leaving” doesn’t mean that the U.S. would cease to engage with regional states or otherwise climb back behind a dreaded “isolationist wall.” It simply is to argue there are other levers of power America could employ in the place of military forces and bases, leaving it free to devote resources to other priorities—military and otherwise—while also avoiding costly entanglements, as the Middle East continues to undergo societal and political transformation in the years ahead. At a minimum, why not revert to the Cold War-era posture of only two main bases, selecting the optimal candidates from among the dozen or so major facilities from which it now operates, while closing the rest?

Whatever form a drawdown takes, there must be a coherent plan for managing any transition by the U.S. to a reduced basing architecture in the Middle East. A major withdrawal by America from its numerous bases will have a major regional impact and could in itself be destabilizing to a degree. This is especially true with regard to U.S. presence in the GCC, where America functions as much as an internal referee as a defender against external forces. For example, in 2017, the Trump administration reportedly stopped an attack on Qatar’s gas fields by talking Saudi Arabia out of executing it.41McFarlane, Said, and Amon, “Oil-Rich Saudi Arabia.”

On the other hand, it is worth considering the removal of America’s immediate military protection could prompt its erstwhile partners to reconsider their own positions and conduct their external relations with greater circumspection. The phenomenon of “moral hazard” enters the equation here; U.S. protection can have the unwanted effect—in some cases—of emboldening those under its umbrella to undertake riskier behavior knowing that the U.S. military insulates them from the full consequences of their actions. Removing that protection reintroduces the threat of more severe penalties. Ideally, a reduction in U.S. presence and a lessening of its direct involvement in Middle Eastern security commitments would have a sobering effect on its current partners (such as Saudi Arabia), pushing them toward greater reliance on diplomacy and compromise, as opposed to bluster and threats.42There may be some indication that this is already happening as doubts have arisen about the fidelity of U.S. commitments to the region under the Trump administration. Ostensibly put forward as a criticism, David Ignatius has argued that questions over U.S. willingness to act militarily in the defense of the GCC may be driving increased diplomatic efforts to resolve the conflict in Yemen and to otherwise reduce tensions with Iran. See David Ignatius, “Belligerents in the Persian Gulf Are Trying Something New: Diplomacy,” Washington Post, November 26, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/belligerents-in-the-persian-gulf-are-trying-something-new-diplomacy/2019/11/26/2f7cd13e-1093-11ea-b0fc-62cc38411ebb_story.html.

Either way, the effect America has on its military partners will need to be considered as carefully as the potential risks associated with adversaries. But here, too, the Cold War offers a useful example: The U.K. conducted its own strategic exit from the Middle East starting in the late 1960s as part of a broader, decade-long plan to eliminate its military commitments in Asia.43See Simon C. Smith, “Britain’s Decision to Withdraw from the Persian Gulf: A Pattern Not a Puzzle.” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 44, no. 2 (December 8, 2015): 328–51. A similar timetable would be useful for reshaping America’s posture in the region. First, it would provide ample time for the considerable logistical challenges of shuttering bases and withdrawing equipment and personnel. Second, it would afford a longer strategic horizon as America assessed how far it wanted to draw down and how much risk it was willing to accept to its position. Finally, it would allow states of the region to prepare for and adjust to a security environment with a drastically decreased level of American military involvement.

But such a plan obviously cannot take shape until there is stronger political will to force a serious re-evaluation of the regional footprint—and with it the overall strategic approach of America to the Middle East. Examining carefully America’s Cold War posture could be one guide (and spark) to this discussion, as policymakers hopefully weigh a regional approach that employs other levers of national power more robustly rather than a default resort to military forces and continued reliance on the extensive basing infrastructure needed to support them.

Endnotes

- 1For the purposes of this paper, the term “Middle East” largely reflects the area as it was defined in the early years of the Cold War with some minor modifications. In 1957, in response to a Congressional query, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles quoted Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs John N. Jernegan, who defined the region as “the area lying between and including Libya on the west and Pakistan on the east and Turkey on the north and the Arabian Peninsula to the south.” Dulles went on to append the Sudan and Ethiopia to Jernegan’s definition, but those states now more comfortably fit into AFRICOM’s area of responsibility and (along with Djibouti) are omitted from the boundaries of “the Middle East” used here, reverting instead to Jernegan’s unaltered definition. For Dulles’s comments, see U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, Subcommittee on Foreign Economic Policy of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, Amendment to the Anglo-French Financial Agreement: Hearings before the Subcommittee on Foreign Economic Policy of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, 85th Cong., 1st Sess., 1957, 354–355.

- 2Figures for 2008 force levels taken from: U.S. Library of Congress. Congressional Research Service, Troop Levels in the Afghan and Iraq Wars, FY2001–FY2012: Cost and Other Potential Issues, by Amy Belasco, R40682 (2009), 6. The 2019 estimate of 50,000 personnel deployed in the region was derived from a country-by-country assay building off various open-source documents. Country-specific force levels can be found in the chart accompanying this article. Sources consulted were: “Incirlik AB—Quick Overview,” Military Installations. Department of Defense, https://installations.militaryonesource.mil/military-installation/incirlik-ab; Alexa Liautaud, “How Many Troops Are Serving in America’s Legacy Wars? We Still Really Don’t Know,” NBC News, November 11, 2019, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/how-many-troops-are-serving-america-s-legacy-wars-we-n1079531; John Vandiver, “U.S. Troops Deployed to Israel Get a New Barracks,” Stars & Stripes, September 19, 2017, https://www.stripes.com/news/us-troops-deployed-to-israel-get-a-new-barracks-1.488440; Phil Stewart, “Exclusive: U.S. Military Completes Pullback from Northeast Syria, Esper Says,” Reuters, December 5, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-usa-syria-exclusive/exclusive-us-military-completes-pullback-from-northeast-syria-esper-says-idUSKBN1Y90CU; “Text of a Letter from the President to the Speaker of the House of Representatives and the President Pro Tempore of the Senate,” The White House, December 11, 2019, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/text-letter-president-speaker-house-representatives-president-pro-tempore-senate-8/; U.S. Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, Bahrain: Unrest, Security, and U.S. Policy, 95-1013 (2019), 2; U.S. Library of Congress. Congressional Research Service. Kuwait: Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy, RS21513 (2019), 7-8; U.S. Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, The United Arab Emirates: Issues for U.S. Policy, RS21513 (2019), 18; and Joseph Votel, “The Posture of U.S. Central Command. Terrorism and Iran: Challenges in the Middle East,” House Armed Services Committee, February 27, 2018, 31, https://docs.house.gov/meetings/AS/AS00/20180227/106870/HHRG-115-AS00-Wstate-VotelJ-20180227.pdf.

- 3A sentiment perfectly captured in the headline of this story on the U.S. “withdrawal” from Syria in October 2019: Eric Schmitt and Helene Cooper, “Hundreds of US Troops Leaving, Also Arriving, in Syria.” New York Times, October 30, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/30/world/middleeast/us-troops-syria-trump.html.

- 4Mara E. Karlin and Tamara Cofman Wittes, “America’s Middle East Purgatory,” Foreign Affairs 98, no. 1 (2020): 88–100.

- 5For 2018, the Middle East and North Africa collective GDP was $3.611 trillion of the $89.91 trillion total global GDP. See “GDP (Current US$) – Middle East & North Africa,” The World Bank, accessed January 30, 2020, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=ZQ; and “GDP (current US$),” The World Bank, accessed January 30, 2020, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD.

- 6Anand Toprani, “Oil and the Future of U.S. Strategy in the Persian Gulf,” War on the Rocks, May 15, 2019, https://warontherocks.com/2019/05/oil-and-the-future-of-u-s-strategy-in-the-persian-gulf/.

- 7Dwight D. Eisenhower, Special Message to Congress (Eisenhower Doctrine), (speech, Washington, DC, January 5, 1957), Miller Center at University of Virginia, https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches/january-5-1957-eisenhower-doctrine.

- 8For more on Kabkan, see Hedrick Smith, “Ex‐CIA. Aide Tells of Life at Iran Listening Post,” New York Times, March 3, 1979, https://www.nytimes.com/1979/03/03/archives/excia-aide-tells-of-life-at-iran-listening-post-catandmouse-game.html. On the U2 base at Peshawar, see “Airgram A–550 From the Embassy in Pakistan to the Department of State, October 6, 1969,” Foreign Relations of the U.S., 1969–1976, Volume E–7, Documents on South Asia, 1969–1972, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76ve07/d38. On U.S. bases in Morocco during the 1950s, see “Memorandum from the Acting Assistant Secretary of State for European Affairs (Elbrick) to the Secretary of State, May 31, 1956,” Foreign Relations of the U.S., 1955–1957, Africa, Volume XVIII, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1955-57v18/d193.

- 9Bruce Riedel, Kings and Presidents: Saudi Arabia and the U.S. since FDR (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2018), 35.

- 10F. Gregory Gause, The International Relations of the Persian Gulf (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 22.

- 11For more on the devolution of the British military posture in the Middle East from the end of the Second World War through the 1950s, see Karol R. Sorby, “Great Powers and the Middle East after World War II (1945-1955),” Asian and African Studies 10, no. 1 (2001): 65–70.

- 12Riedel, Kings and Presidents, 35.

- 13John T. Correll, “The Yom Kippur Airlift,” Air Force Magazine, June 24, 2016, https://www.airforcemag.com/article/the-yom-kippur-airlift/.

- 14David B. Crist, “Joint Special Operations in Support of Operation Earnest Will,” Joint Force Quarterly, Autumn-Winter (2001-02): 15–22.

- 15750 troops from the 82nd Airborne were en route to the region at the time of writing, with an additional 4,000 expected to follow in the coming weeks. It’s unclear if all of those forces will be deployed immediately in Iraq, or if, instead, they will be on “standby” in Kuwait. See Shawn Snow, Howard Altman, and Philip Athey, “750 Soldiers with 82nd Airborne Headed for CENTCOM, Additional 4,000 Troops Expected to Deploy as Iran Tensions Mount,” Military Times, December 31, 2019, https://www.militarytimes.com/flashpoints/2020/01/01/750-soldiers-with-82nd-airborne-headed-for-centcom-additional-4000-troops-expected-to-deploy-as-iran-tensions-mount/.

- 16Stewart, “Exclusive: U.S. Military Completes Pullback from Northeast Syria, Esper Says.”

- 17“Text of a Letter,” The White House.

- 18“Text of a Letter,” The White House.

- 19U.S. Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, Kuwait: Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy, RS21513 (2019), 7–8.

- 20Ramadan Al. Sherbini, “Key U.S. Military Air Hub to Open in Kuwait,” Gulf News, July 13, 2018, https://gulfnews.com/world/gulf/kuwait/key-us-military-air-hub-to-open-in-kuwait-1.2250807.

- 21Sarah McFarlane, Summer Said, and Michael Amon. “Oil-Rich Saudi Arabia Barrels into the Gas Business,” Wall Street Journal, May 22, 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/oil-rich-saudi-arabia-barrels-into-the-gas-business-11558549343.

- 22Vandiver, “U.S. Troops Deployed to Israel Get a New Barracks.”

- 23“Text of a Letter,” The White House.

- 24Sherbini, “Key U.S. Military Air Hub to Open in Kuwait.”

- 25“Manama [Juffair], Bahrain [Al Manamah] 26°14’10’N 50°34’59’E,” Global Security, accessed January 30, 2020, https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/facility/manama.htm.

- 26U.S. Library of Congress, Bahrain: Unrest, Security, and U.S. Policy.

- 27See Joshua Rovner and Caitlin Talmadge, “Hegemony, Force Posture, and the Provision of Public Goods: The Once and Future Role of Outside Powers in Securing Persian Gulf Oil,” Security Studies 23 (2014): 559, 566–567.

- 28Consider that the U.S. accounted for 18% of total oil production in 2018, compared to 12% for Saudi Arabia, while Russia produced 11%. See “What Countries Are the Top Producers and Consumers of Oil?” U.S. Energy Information Administration, November 6, 2019, https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=709&t=6.

- 29Riedel, Kings and Presidents, 103–106.

- 30Anthony H. Cordesman and Abdullah Toukan, “Iran and the Gulf Military Balance (Working Draft),” Center for Strategic and International Studies, October 3, 2016, https://csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/161004_Iran_Gulf_Military_Balance.pdf.

- 31Cordesman and Toukan, “Iran and the Gulf” 24, 36–38.

- 32Cordesman and Toukan, “Iran and the Gulf,” 79.

- 33On the state of the Iranian economy, see Keith Johnson, “Iran’s Ecoomy Is Crumbling but Collapse Is a Long Way Off,” Foreign Policy, February 13, 2019, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/02/13/irans-economy-is-crumbling-but-collapse-is-a-long-way-off-jcpoa-waivers-sanctions/.

- 34Michael Young, “How Deep Is Anti-Iranian Sentiment in Iraq?” Carnegie Middle East Center, November 14, 2019, https://carnegie-mec.org/diwan/80313.

- 35As an example, see Ben Hubbard, Anton Troianovski, Carlotta Gall, and Patrick Kingsley, “In Syria, Russia Is Pleased to Fill an American Void,” New York Times, October 15, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/15/world/middleeast/kurds-syria-turkey.html.

- 36Declan Walsh, “The Tragedy of Saudi Arabia’s War,” New York Times, October 26, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/10/26/world/middleeast/saudi-arabia-war-yemen.html.

- 37Marwan Muasher, “The Next Arab Uprising,” Foreign Affairs 97, no. 6 (2018): 113–24.

- 38See Richard McDaniel, “No ‘Plan B’: U.S. Strategic Access in the Middle East and the Question of Bahrain,” Policy Paper, Brookings Institution, 2013, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/24-us-strategic-access-middle-east-bahrain-mcdaniel.pdf.

- 39This is even more so the case when one factors in the overall questionable record of defeating jihadist elements through force alone over the long term. See, for example, the conclusions of the congressionally mandated study undertaken by the Center for Naval Analyses: Julia McQuaid, Jonathan Schroden, Pamela G. Faber, P. Kathleen Hammerberg, Alexander Powell, Zack Gold, David Knoll, and William Rosenau, Independent Assessment of U.S. Government Efforts against Al-Qaeda (Arlington, VA: Center for Naval Analyses, 2017).

- 40Melissa G. Dalton and Mara E. Karlin, “Toward A Smaller, Smarter Force Posture in the Middle East.” Defense One, August 26, 2018, https://www.defenseone.com/ideas/2018/08/toward-smaller-smarter-force-posture-middle-east/150817/.

- 41McFarlane, Said, and Amon, “Oil-Rich Saudi Arabia.”

- 42There may be some indication that this is already happening as doubts have arisen about the fidelity of U.S. commitments to the region under the Trump administration. Ostensibly put forward as a criticism, David Ignatius has argued that questions over U.S. willingness to act militarily in the defense of the GCC may be driving increased diplomatic efforts to resolve the conflict in Yemen and to otherwise reduce tensions with Iran. See David Ignatius, “Belligerents in the Persian Gulf Are Trying Something New: Diplomacy,” Washington Post, November 26, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/belligerents-in-the-persian-gulf-are-trying-something-new-diplomacy/2019/11/26/2f7cd13e-1093-11ea-b0fc-62cc38411ebb_story.html.

- 43See Simon C. Smith, “Britain’s Decision to Withdraw from the Persian Gulf: A Pattern Not a Puzzle.” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 44, no. 2 (December 8, 2015): 328–51.

Events on Middle East