December 1, 2021

Phantom empire: The illusionary nature of U.S. military power

Key points

- The U.S. has become a “Phantom Empire,” a country that appears to be powerful because it has a robust military presence abroad but cannot use garrisoned forces to achieve geopolitical objectives.

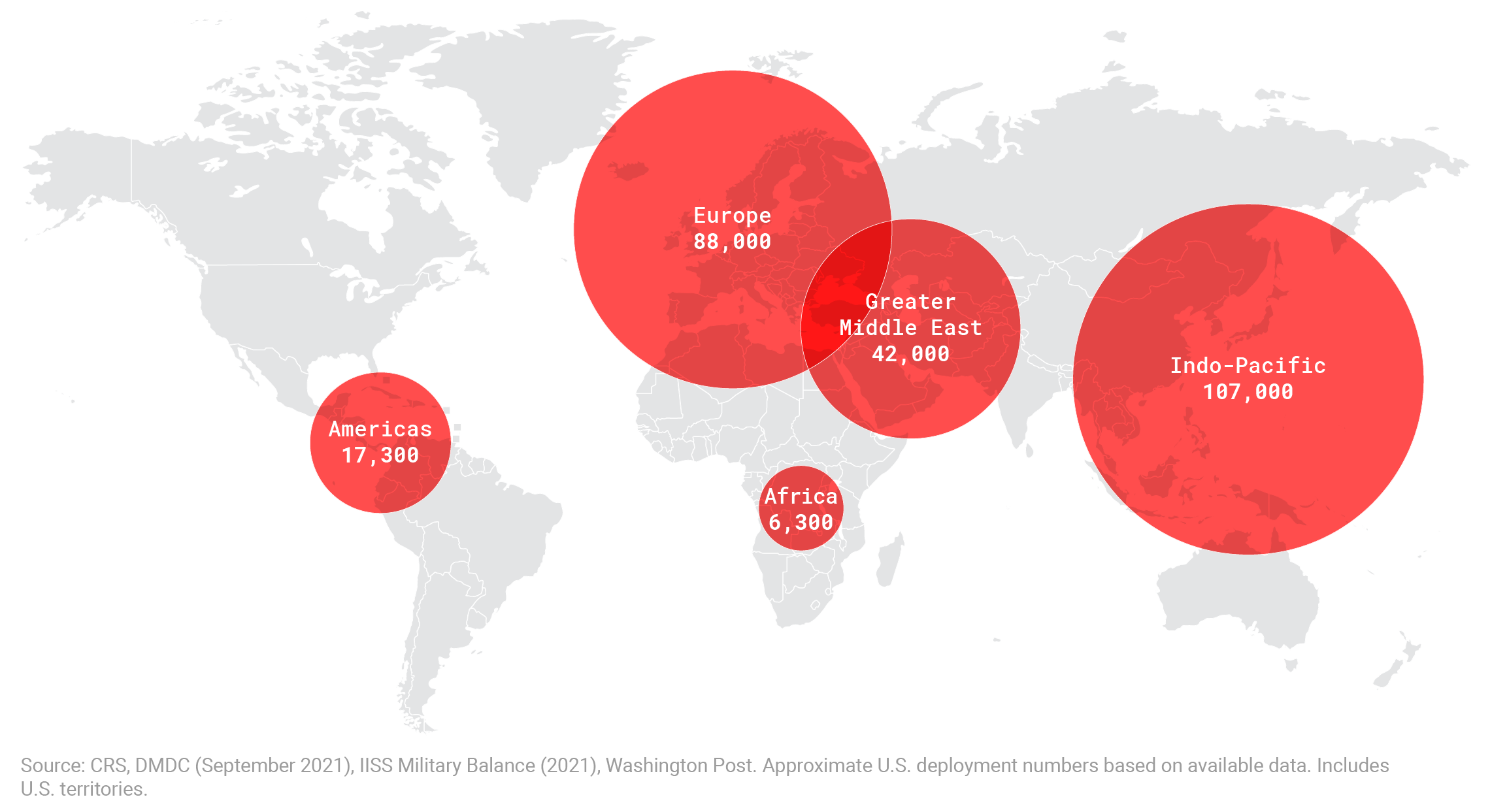

- More than 225,000 U.S. troops and DoD personnel are stationed abroad in more than 150 countries. The largest deployments are to wealthy U.S. allies (Japan, Germany, and South Korea) capable of defending themselves.

- U.S. leaders often justify military commitments by arguing they preserve “influence.” But because American leaders are committed, in most cases, to maintaining troops abroad as a good in and of itself, the U.S. squanders most of its leverage to influence hosts. Threats to withdraw troops are not credible, making them irrelevant for most U.S. geopolitical goals.

- The sources of U.S. power and influence are ultimately rooted in economic prosperity and soft power. A foreign policy that cultivates these sources of strength over maintaining military commitments would better achieve U.S. geopolitical goals.

The limits of leverage over allies and partners

The United States is a “Phantom Empire.” Its array of military deployments and alliances does not much affect its ability to influence the countries it is occupying or defending, or does so only rarely. Most American leaders argue troop deployments are a benefit, not a cost, and say so frequently. Because they clearly want to keep troops in foreign countries, they have little leverage over partners and allies.

Historically, military occupation has been an exercise in raw power. Nations have sought to place their troops on foreign soil, and potential hosts have resisted, based on the idea that armed forces on the ground help the occupying country achieve its foreign policy goals. The most straightforward way to accomplish this is through displacing an existing regime by force or maintaining the ability to do so. This has been part of the logic of empire throughout history, from the ancient world to the colonial powers of recent centuries.

Something appears to have changed in modern international politics. Consider that the United States today has approximately 28,000 troops in South Korea.1Gordon Lubold, Michael R. Gordon, and Andrew Jeong, “U.S., South Korea Near a Deal Over Cost of U.S. Forces on Peninsula,” Wall Street Journal, February 26, 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-south-korea-near-a-deal-over-cost-of-u-s-forces-on-peninsula-11614345296. American forces are there to defend against a potential attack from North Korea, a nuclear-armed nation with an army larger than that of its neighbor.2“Chapter Six: Asia,” The Military Balance Volume 121, Issue 1 (2021), International Institute for Strategic Studies (London, IISS): 218–313. Yet on issue after issue, the South Korean government has butted heads with Washington. Despite the United States making it a top priority to limit Chinese influence in recent years, South Korea has welcomed Huawei as a 5G provider and protested American efforts to hinder the growth of the company.3David P. Goldman, “South Korea Is the Pivot in the Huawei Wars,” Asia Times, May 30, 2020, https://asiatimes.com/2020/05/south-korea-is-the-pivot-in-the-huawei-wars/. South Korea has also refused even to provide rhetorical condemnation of China’s actions in Hong Kong and Xinjiang, and it has disagreed with Washington’s approach to North Korea.4Christian Davies, “South Korea Longs for Trump’s Focus as Efforts to Engage Pyongyang Stall,” Financial Times, November 21, 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/07ae391a-b48b-40c9-ad20-66488a7876d1. Despite the United States permanently garrisoning troops on South Korean territory, Washington has shown little ability to rely on its ally to help it achieve foreign policy goals.

The situation in South Korea is not unique. From Europe to the Middle East to East Asia, the United States has found the process of translating military presence into influence far from straightforward. Some argue the United States must maintain its military commitments to preserve American political influence abroad.5“Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy,” U.S. Department of Defense, accessed November 9, 2021, https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2018-National-Defense-Strategy-Summary.pdf. Yet such arguments misunderstand modern geopolitics and what makes the United States different from great powers of the past. The United States, thankfully, does not use its military to overthrow allied governments it disagrees with. This leaves the threat of withdrawing military support the only potential source of leverage that troops abroad could bring. Yet foreign policy elites almost universally oppose bringing military personnel home or rethinking, let alone reducing, security guarantees. According to Hillary Clinton, speaking as secretary of state in 2010, commitments like NATO should be “embedded in the DNA of American foreign policy.”6Hillary Clinton, “Remarks on the Obama Administration’s National Security Strategy,” U.S. Department of State, May 27, 2010, https://2009-2017.state.gov/secretary/20092013clinton/rm/2010/05/142312.htm.

This report begins by discussing the implicit theory behind keeping military personnel abroad. Intellectuals and government officials regularly argue that bases and troops help accomplish U.S. policy objectives. A review of U.S. foreign policy in Europe, the Middle East, and East Asia yields several examples of countries with close defense relationships with the United States that have gone their own way geopolitically.

U.S. military and DoD personnel deployed overseas

Unlike any other nation, the U.S. permanently stations hundreds of thousands of personnel, and hundreds of bases to house them, far beyond its borders.

Why troops abroad do not increase American influence

The concept of power is central to the study of international relations, and most definitions center around the ability of an actor to get others to do what they otherwise would not.7Jeffrey Hart, “Three Approaches to the Measurement of Power in International Relations,” International Organization Volume 30, Issue 2 (April 1976): 289–305. In this formulation, a military presence abroad can be translated into influence, or the ability of the U.S. government to get other countries to follow its lead on important issues. Much of Washington has embraced the idea that military commitments translate easily into power. This includes the Department of Defense (DoD), which changed its explicit mission in early 2018. Before, the goal of the DoD was to “deter war and to protect the security of our country.” Now, it is “to defend the security of our country and sustain American influence abroad,” thus implying that influence is a matter of military capabilities.8Paul Szoldra, “Trump’s Pentagon Quietly Made a Change to the Stated Mission It’s Had for Two Decades,” Task and Purpose, June 29, 2018, https://taskandpurpose.com/code-red-news/pentagon-mission. The National Security Strategy of the United States released that same year uses similar language.9“Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy,” U.S. Department of Defense.

Pundits and officials treat nearly every attempt to scale back military commitments as hindering U.S. objectives. A headline in Foreign Policy during the 2016 presidential campaign argued that “Donald Trump Doesn’t Understand the Value of U.S. Bases Overseas.”10Kathleen H. Hicks, Michael J. Green, and Heather A. Conley, “Donald Trump Doesn’t Understand the Value of U.S. Bases Overseas,” Foreign Policy, April 7, 2016, https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/04/07/donald-trump-doesnt-understand-the-value-of-u-s-bases-overseas/. To illustrate the advantages that stem from commitments abroad, the authors point to Japanese investment in the U.S. economy and economic growth in East Asia without explaining why one can credit these things to foreign bases. U.S. Representative Liz Cheney of Wyoming, among others, has argued that pulling troops out of Germany would decrease American influence in Europe to the benefit of Russia.11Glenn Greenwald, “House Democrats, Working With Liz Cheney, Restrict Trump’s Planned Withdrawal of Troops from Afghanistan and Germany,” Intercept, July 2, 2020, https://theintercept.com/2020/07/02/house-democrats-working-with-liz-cheney-restrict-trumps-planned-withdrawal-of-troops-from-afghanistan-and-germany/; Keir Gils, “Real or Not, Trump’s Germany Withdrawal Helps Putin,” Chatham House, June 8, 2020, https://www.chathamhouse.org/expert/comment/real-or-not-trump-s-germany-withdrawal-helps-putin; Nic Robertson, “Trump’s Germany Troops Pullout May Be His Last Gift to Putin before the Election,” CNN, August 2, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/08/02/politics/trump-germany-troops-russia-intl/index.html. The military presence in Afghanistan was similarly justified as necessary to counter China.12Joseph E. Fallon, “U.S. Geopolitics: Afghanistan and the Containment of China,” Small Wars Journal, July 12, 2013, https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/us-geopolitics-afghanistan-and-the-containment-of-china.

Academic and think tank proponents of the current alliance structure likewise see it as a rich source of influence for the United States. Lindsey W. Ford and James Goldgeier offer a recent example:

The benefits the U.S. accrues from its alliances stretch far beyond the military domain. America’s allies provide support for U.S. political priorities—such as sanctioning Iran and North Korea’s illicit weapons programs and providing financial support for reconstruction efforts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Allies such as Japan are working together with the U.S. to advance fair and transparent international standards on issues such as digital governance and cyber security. And within the G-7, U.S. allies have coordinated to address issues ranging from the global refugee crises, to international health standards, and education for women and children.13Lindsey W. Ford and James Goldgeier, “Who Are America’s Allies and Are They Paying Their Fair Share of Defense?” Brookings Institution, December 17, 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/policy2020/votervital/who-are-americas-allies-and-are-they-paying-their-fair-share-of-defense/.

In this view, the United States can get what it wants—whether in the realm of economics, security, or human rights—from its alliances. Others have gone so far as to argue that U.S. military commitments abroad are inextricably connected to maintaining the dollar as the world’s reserve currency.14Stephen G. Brooks, G. John Ikenberry, and William C. Wohlforth, “Don’t Come Home, America: The Case against Retrenchment,” International Security Volume 37, Issue 3 (2013): 7–51, 44–46.

There have also been quantitative attempts to make a connection between American troops abroad and favorable policy outcomes. According to a 2016 RAND Corporation study, a military presence in a foreign country increases bilateral trade between the United States and that nation.15Daniel Egel, Adam R. Grissom, John P. Godges, Jennifer Kavanagh, and Howard J. Shatz, “Estimating the Value of Overseas Security Commitments,” RAND Corporation (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2016): 36. Such an analysis may be biased by one or more lurking variables; having a substantial troop presence in a country is usually the result of a nation’s leaders having good relations with the United States and being ideologically closer to the Washington consensus in favor of open markets, and such factors can increase economic cooperation.16Brian L. Joiner, “Lurking Variables: Some Examples,” American Statistician Volume 35, Issue 4 (1981): 227–233. There is no attempt in the report to account for such possibilities. Moreover, the statistical relationships found are weak, significant at the p < .05 threshold for the presence of Army or Air Force personnel, but not the Navy, Marine Corps, or all troops, raising concerns of a “forking paths” analysis in which data are analyzed or interpreted in a way to extract a result that fits a preconceived theory.17Andrew Gelman and Eric Loken, “The Statistical Crisis in Science: Data-Dependent Analysis—a ‘Garden of Forking Paths’—Explains Why Many Statistically Significant Comparisons Don’t Hold Up,” American Scientist Volume 102, Issue 6 (2014): 460–466. The findings cannot be taken as strong evidence of the effect of military personnel abroad, given the inconsistency of the results, the weakness of the relationships found, and the lack of adequate control variables.18Other studies suffer from similar problems, as positive relationships between troop presence and favorable outcomes are always subject to the lurking variable problem. The problem with seeing troops as translating into influence and relying on such studies is that the proposed mechanism is very indirect and therefore uncertain. There is proposed a chain of causation in which there is some relationship between foreign bases and trade, and then trade leads to influence. For the argument to make sense, the effect in the first step of the chain, from troops to trade, would have to be large enough to influence the second step. In other words, the question is not whether more soldiers lead to greater trade, but whether that increase in trade is substantial enough to affect American influence, given all the other factors that influence how much trade flows from one country to another. After all, if the goal is to increase trade, then it could be more efficiently done through policies seeking that end, rather than having it be a byproduct of a policy built around deterrence and influence. Finding weak effects on trade or investment, even setting aside the lurking variable issue, is not enough to show a relationship between an American presence and an increase in U.S. power. The studies showing an impact of U.S. military presence on factors like trade and foreign direct investment do not even attempt to meet this standard. See Glen Biglaiser and Karl DeRouen Jr., “Following the Flag: Troop Deployment and U.S. Foreign Direct Investment,” International Studies Quarterly Volume 51, Issue 4 (2007): 835–854.

If we are to expect American troops to increase U.S. influence, there are two potential mechanisms one might imagine. Most directly, the United States can use force, or the threat thereof, to make a country do what it wants. Generally, this does not happen against allies, and defenders of a robust military presence abroad would disclaim such a right on behalf of U.S. forces in most situations. The other way is to threaten to remove U.S. forces or otherwise scale back commitments—leaving host countries lacking military protection—as leverage to get governments to pursue a different policy. Since the United States is committed to defending allies such as Germany and Japan, presumably, it can threaten to reduce or terminate its obligations to win concessions in negotiations over other issues.

For the theory of leverage to work, American leaders must see the U.S. presence abroad as a cost, not a benefit, or at least credibly pretend to think this way. In any negotiation, the two sides must want different things. If the United States and the countries hosting its forces both want American personnel to stay where they are, then it is difficult to see on what basis negotiations proceed. It is also possible that Washington may have leverage if foreign leaders want American forces to stay more strongly than the United States does.19Nicholas Bardsley, “Dictator Game Giving: Altruism or Artefact?” Experimental Economics Volume 11, Issue 2 (2008): 122–133. In practice, however, it is difficult to negotiate around such preferences, and the United States is very often more committed to alliances than the countries it defends.

Ironically, then, former President Donald Trump’s indifference or hostility toward American commitments abroad put the United States in a better position to achieve foreign policy objectives. The more passionate leaders are about keeping personnel where they are, the less influence they can exercise, since one must convince others to accept American help, rather than holding it out as a carrot to induce cooperation on other issues. President Trump bragged about using his skepticism over the military commitment to South Korea to renegotiate a trade deal.20Veronica Stracqualursi, “Trump Apparently Threatens to Withdraw U.S. Troops from South Korea over Trade,” CNN, March 16, 2018, https://www.cnn.com/2018/03/15/politics/trump-us-troops-south-korea/index.html; Josh Dawsey, Damian Paletta, and Erica Werner, “In Fundraising Speech, Trump Says He Made up Trade Claim in Meeting with Justin Trudeau,” Washington Post, March 15, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-politics/wp/2018/03/14/in-fundraising-speech-trump-says-he-made-up-facts-in-meeting-with-justin-trudeau/. He also sought to increase the funding allies provided toward the cost of stationing U.S. forces, achieving only moderate success. While the South Korean government agreed to cover a larger share of the American presence, the U.S. mission itself was left unchanged, which means that it is still a net cost for the United States.21Choe Sang-Hun, “U.S. and South Korea Sign Deal on Shared Defense Costs,” New York Times, February 10, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/10/world/asia/us-south-korea-military-costs.html. Nonetheless, the experience with South Korea demonstrates that President Trump, by being more skeptical of American commitments, may have been better able to use U.S. bases abroad to apply pressure on an ally.

Part of the reason President Trump was not better able to use his leverage was domestic hostility to any attempts to reduce American commitments abroad, including from his appointees. Throughout his administration, top officials such as National Security Advisor John Bolton, Secretary of Defense James Mattis, and National Security Advisor H.R. McMaster tried to thwart moves toward a more restrained foreign policy consistent with some of President Trump’s instincts.22Bob Woodward, Fear: Trump in the White House (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2018); John Bolton, The Room Where It Happened (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2020). In 2018, Congress expressed support for Article V of the NATO treaty by a unanimous vote in the House and a vote of 97-2 in the Senate.23Brett Samuels, “House Passes Resolution in Support of NATO by Unanimous Voice Vote,” Hill, July 11, 2018, https://thehill.com/homenews/house/396536-house-passes-resolution-in-support-of-nato-by-unanimous-voice-vote. Two years later, the vast majority of Republicans in both houses of Congress voted with Democrats to rebuke President Trump over his stated goal of pulling out of Syria.24Karoun Demirjian, “Senate Rebukes Trump’s Plan to Withdraw U.S. Forces from Syria, Afghanistan,” Washington Post, January 31, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/powerpost/senate-backs-mcconnells-rebuke-of-trumps-military-drawdown-plans-in-syria-afghanistan/2019/01/31/5812d058-2584-11e9-90cd-dedb0c92dc17_story.html; Catie Edmondson, “In Bipartisan Rebuke, House Majority Condemns Trump for Syria Withdrawal,” New York Times, October 16, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/16/us/politics/house-vote-trump-syria.html. Officials in President Trump’s own administration reportedly deceived the White House about the number of U.S. troops stationed in Syria.25Katie Bo Williams, “Outgoing Syria Envoy Admits Hiding US Troop Numbers; Praises Trump’s Mideast Record,” Defense One, November 12, 2020, https://www.defenseone.com/threats/2020/11/outgoing-syria-envoy-admits-hiding-us-troop-numbers-praises-trumps-mideast-record/170012/. The administration had trouble confirming presidential appointees who favored a less robust military presence abroad, and therefore relied on hawks to fill top positions, even when they had views that conflicted with those of the president.26Akbar Shahid Ahmed, “Mitch McConnell Is about to Doom One of Trump’s Attempts to ‘End Endless War,’” Huffington Post, September 18, 2020, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/trump-endless-wars-afghanistan_n_5f64e5b7c5b6b9795b1000bb.

In an era in which partisanship dominates nearly all aspects of American politics, foreign policy remains an area where both sides of the aisle find a great deal to agree on and where Republicans during the last administration pushed back seriously against President Trump.27Jordan Tama, Joshua Busby, Craig Kafura, Joshua D. Kertzer, and Jonathan Monten, “Congress has NATO’s Back, Despite Trump’s Unilateralism,” Washington Post, April 3, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/04/03/congress-has-natos-back-despite-trumps-unilateralism/. This matched broad trends observed during the Obama administration, when the president felt boxed into surging an additional 30,000 U.S. troops into Afghanistan by Congress and the Pentagon.28Ben Rhodes, The World as It Is: A Memoir of the Obama White House (New York, NY: Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2019): 62–72. President Joe Biden has talked of alliances as “sacred commitments,” taking the debate out of the realm of any kind of serious cost-benefit analysis.29Joseph Simonson, “‘Our Alliances Will Be Completely Fractured’: Biden Claims ‘There Will Be No NATO’ If Trump Wins Second Term,” Washington Examiner, November 24, 2019, https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/news/our-alliances-will-be-completely-fractured-biden-claims-there-will-be-no-nato-if-trump-wins-second-term.

Given the deep commitment among Washington elites to maintaining a robust military presence across the globe, we should not expect U.S. forces to provide leverage in foreign negotiations. Leaders cannot credibly threaten to scale back American commitments in an effort to get concessions in other policy areas, such as those related to economics or human rights, since all parties to any potential negotiation know what the U.S. position is. In fact, there is little indication that they try, although that could change with an administration more disciplined and focused on exerting its leverage to advance U.S. security and prosperity. This would require a fundamental shift from how Washington has viewed alliances over the last several decades. Across Europe, the Middle East, and East Asia, military commitments are all but irrelevant in determining whether the United States can achieve major diplomatic goals that require cooperation with allies.

NATO after the collapse of the Soviet Union

The United States maintains more than 47,400 permanent military personnel in Germany, 15,000 in Italy, and 10,800 in the United Kingdom.30“Military and Civilian Personnel by Service/Agency by State/Country, June 2021,” Defense Manpower Data Center, U.S. Department of Defense, accessed October 25, 2021, https://dwp.dmdc.osd.mil/dwp/api/download?fileName=DMDC_Website_Location_Report_2106.xlsx&groupName=milRegionCountry. Smaller contingents of troops are stationed elsewhere across the continent, with the largest deployments in Spain, Belgium, and Poland. Originally placed in Western Europe during World War II, and left there to deter the Soviet Union, American soldiers are still said to be on the continent today to “stand up to Russia.” Yet there is little evidence the U.S. military presence matters much in disputes between Washington and Moscow.

European nations occasionally push back against Russia, but when they have it has mostly been due to Russia’s actions, not U.S. pressure. Moscow has faced sanctions over its seizure of Crimea and support for separatists in Ukraine.31“E.U. Restrictive Measures in Response to the Crisis in Ukraine,” European Council, Council of the European Union, accessed November 9, 2021, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/sanctions/ukraine-crisis/. Yet countries in central and eastern Europe that are part of NATO each take their own path in their dealings with Russia. Poland has taken a hard line in recent years, while Hungary has been an ally, criticizing sanctions.32Valerie Hopkins, Michael Peel, and Henry Fox, “Orban-Putin Talks Compound Disquiet over Hungary’s Russia Ties,” Financial Times, August 13, 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/9a1988e4-f8ff-11e9-a354-36acbbb0d9b6. In countries like Italy and France, whether the government favors a tougher or weaker line on Russia has depended on electoral outcomes, not U.S. pressure. For years, Washington tried to prevent the building of Nord Stream 2, a pipeline to bring Russian gas into Germany. Despite this considerable pressure, which included warnings from the State Department that any entity connected to the pipeline could be exposed to U.S. sanctions, Germany remained broadly supportive of the Nord Stream 2 project, and in May, the Biden administration finally dropped opposition to it.

In addition to having little impact on issues pertaining to Russia, the NATO alliance has not prevented countries that rely on the United States for defense from pursuing policies Washington opposes. Commentators have worried that Hungary and Poland have moved in an “illiberal” direction in recent years, and nothing about their membership in NATO has prevented this supposed shift, despite concerns shown by officials during the Obama administration.33Patrick Kingsley, “Hungary’s Leader Was Shunned by Obama, but Has a Friend in Trump,” New York Times, August 15, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/15/world/europe/hungary-us-orban-trump.html. The United States has found itself on the opposite side of Turkey on a wide range of issues, including the civil wars in Syria and Libya, and has watched as President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has consolidated power and jailed critics of his government. The split between some members of NATO is such that countries like Hungary, Poland, and Turkey have been referred to as “obstacles to liberal internationalism” in a way that makes their current direction antithetical to the founding principles of the alliance.34Alexandra Gheciu, “NATO, Liberal Internationalism, and the Politics of Imagining the Western Security Community,” International Journal Volume 74, Issue 1 (2019): 32–46.

The dispute over Turkey’s purchase of an S-400 Russian air defense system highlights the failure of U.S. forces there to provide diplomatic leverage. Turkey originally moved into the western camp over its tensions with the Soviet Union, which began when the latter sought control over the Black Sea and a base in the Dardanelles in the post-World War II settlement.35Deborah Welch Larson, Origins of Containment: A Psychological Explanation (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1985). Almost three-quarters of a century later, the Soviet Union has collapsed, and there is little military threat to Turkey from its successor. In 2019, the United States threatened to impose sanctions on Turkey for buying Russian military technology.36Humeyra Pamuk, “Turkey Should Scrap Russian Missile System or Face U.S. Sanctions: White House Official,” Reuters, November 10, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-turkey-security-usa/turkey-should-scrap-russian-missile-system-or-face-u-s-sanctions-white-house-official-idUSKBN1XK0JS. The next year, another contract was signed between Russia and Turkey, this one allowing for a second batch of the system to be sent, after which the proposed sanctions were implemented.37“Russia, Turkey Sign Deal for Supply of S-400 Missile Systems to Ankara,” Middle East Monitor, August 24, 2020, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20200824-russia-turkey-sign-deal-for-supply-of-s-400-missile-systems-to-ankara/; Amanda Macias, “U.S. Sanctions Turkey Over Purchase of Russian S-400 Missile System,” CNBC, December 15, 2020, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/12/14/us-sanctions-turkey-over-russian-s400.html. While NATO is still presented as necessary to stand up to Russia, the United States feels the need to economically punish one of its allies for building military links with the same country. Some recognize the absurdity of this situation. Though there are scattered calls from prominent observers for U.S. forces to leave Turkey, and to remove U.S. nuclear weapons there, there is little evident support for such ideas among officials.38Mike Sweeney, “Reconsidering U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe,” Defense Priorities, September 14, 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/reconsidering-us-nuclear-weapons-in-europe; Charles Wald, “Pull U.S. Troops Out of Turkey: Former EUROCOM Deputy,” Breaking Defense, December 4, 2019, https://breakingdefense.com/2019/12/pull-us-troops-out-of-turkey-former-eucom-deputy/. It seems American officials want to be in Turkey, probably more than the Turks want them there.

Permanently assigned U.S. military personnel in Europe

The U.S. military presence in Europe includes tens of thousands of troops and DoD personnel permanently assigned to the continent, and many additional forces on rotational deployments.

After helping rid Europe of Nazism, the United States never left. Its postwar practice of keeping troops in conquered nations, justified as a check on potential Soviet expansion, was a break from historical practice but widely accepted within the democratic systems of the nations of the continent.39Sebastian Schmidt, “Foreign Military Presence and the Changing Practice of Sovereignty: A Pragmatist Explanation of Norm Change,” American Political Science Review Volume 108, Issue 4 (2014): 817–829. As international relations scholar G. John Ikenberry argues, the liberal nature of the United States, and its relative non-involvement in the domestic politics of the countries it occupied, may have made its presence more acceptable in Europe and elsewhere.40G. John Ikenberry, After Victory: Institutions, Strategic Restraint, and the Rebuilding of Order after Major Wars (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2019). Yet this is another way of saying that a foreign military presence forgoes one potential source of leverage for exercising U.S. power abroad. The U.S. commitment to maintain the NATO alliance and keep a large military presence in foreign countries may not only be irrelevant to accomplishing its geopolitical goals, but actually a hinderance, as it is more difficult to place sanctions on allies than friends.

The irrelevance of troops in the Middle East

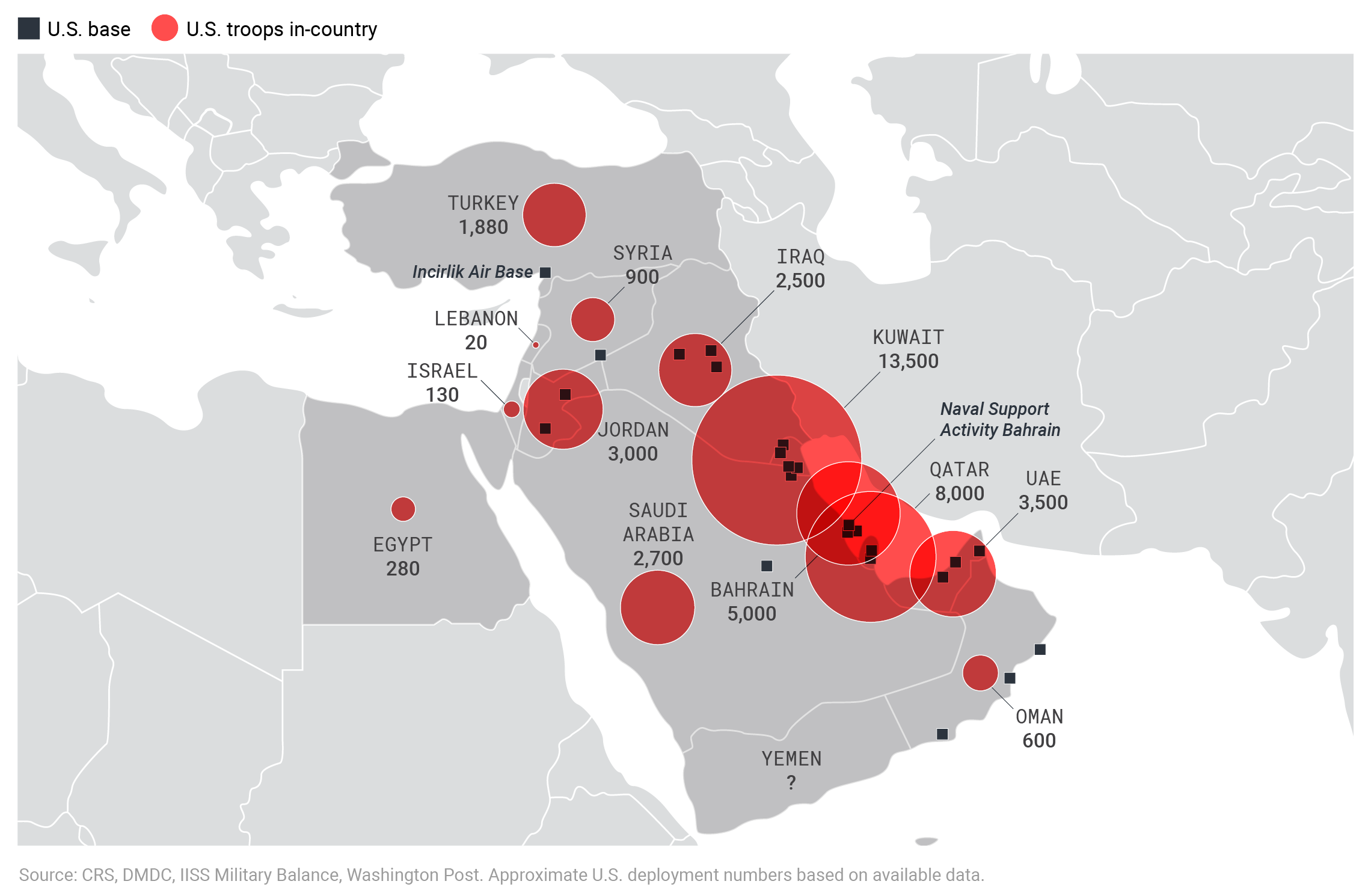

In no region has the United States in recent years invested more blood and treasure than the greater Middle East. Between the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, it has spent trillions of dollars and lost more than 6,500 soldiers. If military commitment and sacrifice led to the accomplishment of U.S. foreign policy objectives, the connection should be most obvious in this region. American Middle East bases, which have proliferated since the end of the Cold War, do provide convenient access to recent warzones.41Mike Sweeney, “A Plan for U.S. Withdrawal from the Middle East,” Defense Priorities, December 21, 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/a-plan-for-us-withdrawal-from-the-middle-east. Yet one cannot credibly argue military bases give the United States significant influence over its partners there, who have increasingly gone their own ways.

U.S. deployments in the Middle East

The U.S. military maintains an outsized basing presence for ground troops in the Middle East, despite the region’s limited and diminishing strategic importance.

Saudi Arabia, hosting 2,700 U.S. personnel as of summer 2021, has been a close partner.42Christopher M. Blanchard, “Saudi Arabia: Background and U.S. Relations (RL33533),” Congressional Research Service, October 5, 2021, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL33533. The Obama administration felt pressured to support the Saudi War in Yemen, a conflict that undermines U.S. interests and values.43Daniel DePetris, “End U.S. Support for War in Yemen,” Defense Priorities, December 8, 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/end-us-support-for-war-in-yemen; Mark Mazzetti and Eric Schmitt, “Quiet Support for Saudis Entangles U.S. in Yemen,” New York Times, March 13, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/14/world/middleeast/yemen-saudi-us.html. The American defense commitment to Saudi Arabia provides little leverage in trying to change its disturbing behavior abroad, which has in recent years included, in addition to the war in Yemen, support for jihadi groups in Syria, a clampdown on internal dissent, and the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi. The point was moot during the Trump administration, which gave the Saudis a blank check on human rights and other issues, but it is noteworthy that even under President Barack Obama, American defense commitments did not help the U.S. position. If anything, they provided cover for reckless Saudi policies abroad since that country could always rely on American help in the case of a wider war. The potential for the United States to use its leverage to change Saudi behavior for the better has been recognized by analysts but never realized by policymakers committed to the status quo.44Ariane M. Tabatabai and Becca Wasser, “Could America Use Its Leverage to Alter the Saudis’ Behavior?” RAND Corporation, November 15, 2018, https://www.rand.org/blog/2018/11/could-america-use-its-leverage-to-alter-the-saudis.html. Qatar likewise has supported jihadis in the Syrian civil war, frustrating American efforts to stand up more “moderate” rebels.45Amena Bakr, “Defying Allies, Qatar, Unlikely to Abandon Favor Syrian Rebels,” Reuters, March 20, 2014, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-syria-crisis-qatar/defying-allies-qatar-unlikely-to-abandon-favored-syria-rebels-idUSBREA2J0WM20140320. Nonetheless, the Trump administration saw in that country the beginning of the expansion of al-Udeid, the largest U.S. airbase in the Middle East.46Adam Taylor, “As Trump Tries to End ‘Endless Wars,’ America’s Biggest Mideast Base Is Getting Bigger,” Washington Post, August 21, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/as-trump-tries-to-end-endless-wars-americas-biggest-mideast-base-is-getting-bigger/2019/08/20/47ac5854-bab4-11e9-8e83-4e6687e99814_story.html.

During the Trump administration, the United States actually sided with Saudi Arabia and other Gulf nations in their dispute with Qatar.47Felicia Schwartz, “Trump Sides With Saudis, Other Gulf States in Rift With Qatar,” Wall Street Journal, June 6, 2017, https://www.wsj.com/articles/trump-says-in-tweet-he-discussed-qatar-with-arab-leaders-1496758326. This crisis lasted from mid-2017 to January 2021 and included a blockade against the latter. Highlighting the strangeness of the entire episode, in the early days of the crisis, as Qatar was worrying about food insecurity, Iran began delivering cargo planes filled with fruits and vegetables.48“Iran Flies Food to Qatar amid Concerns of Shortages,” Reuters, June 11, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-gulf-qatar-iran-idUSKBN1920EG?il=0. By late June 2017, an Iranian official claimed that his government was providing more than 1,000 tons of food a day to Qatar.49“Iran Sends 1,100 Tonnes of Food to Qatar Daily: Report,” Gulf Times, June 23, 2017, https://www.gulf-times.com/story/554288/Iran-sends-1-100-tonnes-of-food-to-Qatar-daily-rep. The United States therefore found itself in an absurd situation in which it was being hosted by a country it opposed, as it was being blockaded by other allies and bailed out by America’s greatest nemesis in the region. As American leaders refuse to see troop deployments as a cost, countries of the Middle East treat their presence as all but irrelevant.

Oil has always been an important consideration in American strategy in the Middle East. Traditionally, the United States was said to need to dominate the region in order to continue to have access to cheap energy.50Andrew Scott Cooper, The Oil Kings: How the U.S., Iran, and Saudi Arabia Changed the Balance of Power in the Middle East (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2012): 20, 202. As the United States developed into a net exporter of oil, the stated policy during the Trump administration actually became to keep the price of that commodity high, or at least high enough to not significantly harm the domestic industry.51Gregory Meyer, “U.S. Is Net Exporter of Oil for First Time in Decades,” Financial Times, November 29, 2019, https://www.ft.com/content/9cbba7b0-12dd-11ea-a7e6-62bf4f9e548a. Military commitments in the Middle East did not prevent the Saudis from last year initiating a “price war” with Russia that some thought was also taking aim at American shale producers.52Sam Meredith, “Who Will Blink First? What an All-Out Price War Means for the U.S., Saudi Arabia and Russia,” CNBC, March 9, 2020, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/03/09/oil-prices-what-a-price-war-means-for-the-us-saudi-arabia-and-russia.html. The motivations of various actors are murky. According to at least one report, it was Russia that initiated the production increases with the aim of harming U.S. oil producers. See Illya Arkhipov, Will Kennedy, Olga Tanas, and Grant Smith, “Putin Dumps MBS to Start a War on America’s Shale Industry,” Bloomberg Quint, March 9, 2020, https://www.bloombergquint.com/business/putin-dumps-mbs-to-start-a-war-on-america-s-shale-oil-industry. Yet it was Saudi Arabia that initiated the “price war” in response. See Anjli Raval, David Sheppard, and Derek Brower, “Saudi Arabia Launches Oil Price War after Russia Deal Collapse,” Financial Times, March 8, 2020, https://www.ft.com/content/d700b71a-6122-11ea-b3f3-fe4680ea68b5. The extent to which either country was motivated by a desire to harm the U.S. oil industry is therefore unclear. In April 2020, President Trump reportedly told Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman that Congress would withdraw U.S. troops from his country if they did not start cutting oil production.53Timothy Gardner, Steve Holland, Dmitry Zhdannikov, and Rania El Gamal, “Special Report: Trump Told Saudi: Cut Oil Supply or Lose U.S. Military Support–Sources,” Reuters, April 30, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-global-oil-trump-saudi-specialreport/special-report-trump-told-saudi-cut-oil-supply-or-lose-u-s-military-support-sources-idUSKBN22C1V4. Less than two months later, Saudi Arabia and Russia agreed to do just that.54Rania El Gamal, Olesya Astakhova, and Alex Lawler, “Saudi, Russia Agree Oil Cuts Extension, Raise Pressure for Compliance,” Reuters, June 3, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-oil-opec/saudi-russia-agree-oil-cuts-extension-raise-pressure-for-compliance-idUSKBN23A1OU. While we do not know whether President Trump’s threat had its intended effect, it may well have, and this would therefore serve as a counterexample to the general rule that the United States does not leverage its military commitments abroad in order to achieve geopolitical ends. Nonetheless, it is important to note how irrelevant American security guarantees were to Saudi decision-making up to that point. Moreover, the threat to scale back the American commitment could only be credibly made when congressional support for Saudi Arabia was already at its nadir due to factors including the war in Yemen and the Khashoggi killing. In other times and places in which there is more domestic support for the U.S. ally or partner, the norm is for such leverage to be much weaker.

Finally, it must be noted that, for all the American military commitments in the Middle East, they have not prevented countries in the region from making common cause with states the United States wants to keep out. Two decades of an American presence in Afghanistan coincided with that country growing closer to China, which was responsible for 79 percent of all foreign direct investment in Afghanistan between 2005 and 2013.55Gregor Aisch, Josh Keller, and K.K. Rebecca Lai, “The World According to China,” New York Times, July 24, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/07/24/business/international/the-world-according-to-china-investment-maps.html. In the other major post-9/11 war, it is well known that removing Saddam Hussein from Iraq strengthened Iran, both weakening a regional rival and allowing it to play a dominant role in Iraqi politics.56For a report on this, based on leaked cables from the Iranian government, see Tim Arango, James Risen, Farnaz Fassihi, Ronen Bergman, and Murtaza Hussain, “The Iran Cables: Secret Documents Show How Tehran Wields Power in Iraq,” New York Times, November 19, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/11/18/world/middleeast/iran-iraq-spy-cables.html. It is questionable whether nations in the greater Middle East achieving economic integration with China or other American rivals actually threatens U.S. interests. Regardless, an American presence in the Middle East is often justified on the grounds that it limits the influence of actors from outside the region, and this is evidently not true.57Michael Doran and Peter Rough, “China’s Emerging Middle Eastern Kingdom,” Tablet, August 2, 2020, https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/israel-middle-east/articles/china-middle-eastern-kingdom; Robert D. Kaplan, “Beijing Fills the Mideast Vacuum,” Wall Street Journal, January 20, 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/beijing-fills-the-mideast-vacuum-11611183756.

East Asia: U.S. military presence, regional drifts toward China

The United States has more than 62,000 troops stationed in Japan, and 28,000 in South Korea. It also has defense partnerships with the Philippines, Australia, and New Zealand. The rise of China has been the fundamental geopolitical story of the last three decades in the Asia-Pacific, if not the entire world. Worried about this reality, the Obama administration in its “pivot to Asia,” which was largely aspirational, sought to shore up alliances and deepen economic ties to preserve American influence in the Far East.58For a skeptical take on the idea of whether the U.S. actually implemented this strategy, see Michal Kolmaš and Šárka Kolmašová, “A ‘Pivot’ That Never Existed: America’s Asian Strategy under Obama and Trump,” Cambridge Review of International Affairs Volume 32, Issue 1 (2019): 61–79. Given economic and geographical realities, the United States may lose its place as the dominant military power in the region.59Richard Hanania, “The Inevitable Rise of China: U.S. Options With Less Indo-Pacific Influence,” Defense Priorities, May 26, 2021, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/the-inevitable-rise-of-china. China is now the largest economy in the world as measured by purchasing power parity, and it will likely soon pass the United States in terms of market exchange rates. Through working with allies, American leaders aspire to get their way on important issues pertaining to economics or human rights. Whether or not this is possible, there is little to indicate the substantial U.S. military presence in the region contributes to achieving such goals.

Perhaps nowhere is this clearer than in the case of South Korea. John Hemmings of the Center for Strategic and International Studies talks of a “security-trade dilemma” facing that nation, which finds itself in the middle of a dispute between China, its main trading partner, and the United States, which provides its security.60John Hemmings and Sunghim Cho, “South Korea’s Growing 5G Dilemma,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, July 7, 2020, https://www.csis.org/analysis/south-koreas-growing-5g-dilemma. This position assumes American leverage over South Korea resulting from the U.S. military presence. But this leverage is extremely limited or non-existent; President Trump’s suggestions about withdrawing from the Korean Peninsula were regularly met with resistance, even from his own cabinet. Although President Trump was able to get South Korea to cover more of the costs of the occupation, which, as mentioned above, still left it as a net cost to the United States, domestic pressure ensured a significant scaling back of commitments in South Korea may have never been a real possibility. Bob Woodward famously wrote that when the president questioned why the United States was even in South Korea, Secretary Mattis replied that it was in the region to “prevent World War III.”61Bob Woodward, Fear: 305. The quote was widely reported as a way of showing how little President Trump understood about the need to maintain military alliances.62Alexandra Hutzler, “Learning Donald Trump Needed to Be Reminded of World War 3 Threat Was Most ‘Illuminating’ Part of Book: Woodward,” Newsweek, September 11, 2018, https://www.newsweek.com/donald-trump-world-war-3-woodward-1115426.

Regardless of whether this view accurately represents reality, as long as U.S. decisionmakers believe the future of humanity depends on keeping troops in East Asia, that presence provides no leverage. It is understandable then why the United States has been frustrated with South Korea on everything from its acceptance of Huawei to its indifference to pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong and participation in a new Chinese bank seeking to finance projects in the developing world.63Song Su-Hyun, “Korean Tech Industry Braces for New U.S. Sanction on Huawei,” Korea Herald, September 10, 2020, http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20200910000782; Tae-jun Kang, “On Hong Kong, South Korea Is Caught between China and U.S.,” Diplomat, May 29, 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2020/05/on-hong-kong-south-korea-is-caught-between-china-and-us/; Jane Perlez, “China Creates a World Bank of Its Own and the U.S. Balks,” New York Times, December 4, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/05/business/international/china-creates-an-asian-bank-as-the-us-stands-aloof.html. In 2017, the world witnessed the strange spectacle of an American administration trying to place the THAAD missile system in South Korea to defend its forces, over the objections of the government it was there to defend.64Uri Friedman, “How to Choose Between the U.S. and China? It’s Not That Easy,” Atlantic, July 26, 2019, https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2019/07/south-korea-china-united-states-dilemma/594850/.

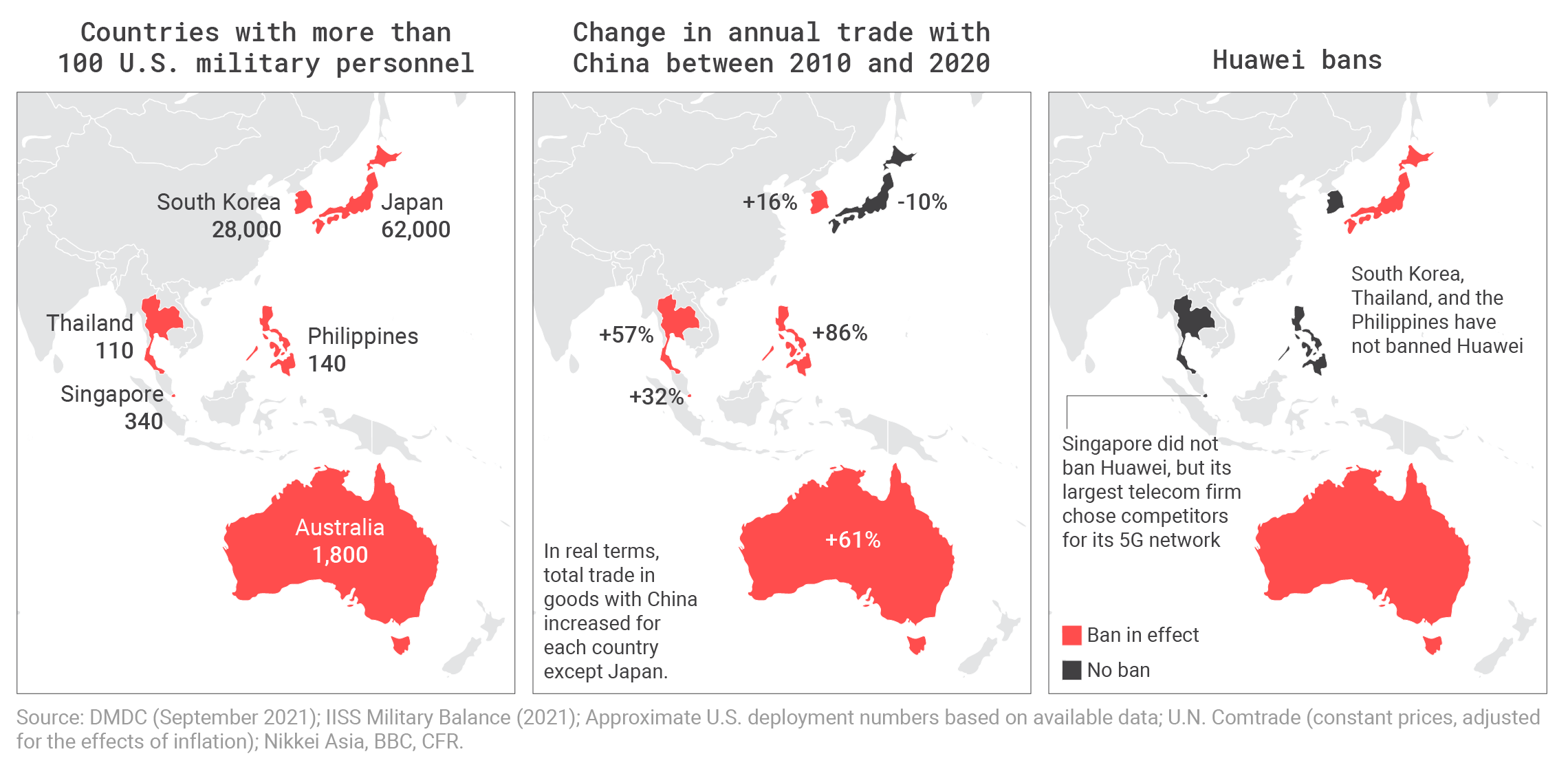

The figure below shows three maps of East Asia. The first highlights the countries that host more than 100 U.S. military personnel. The second shows changes in trade between China and the countries in question from 2010 to 2020, and the third shows which states have enacted Huawei bans. As can be seen, the presence of American troops in various countries does not appear to be doing anything to prevent increasing interdependence with China, nor does it seem conducive to achieving American geopolitical goals like a Huawei ban.

U.S. military presence, regional trade with China, and Huawei bans

The presence of U.S. troops in a country (left) does not stop countries increasing trade with China (middle) or rejecting U.S. requests (right).

In addition to South Korea, one can see similar frustrations in the Philippines. In 2016, President Rodrigo Duterte declared his country was aligning with China over the United States.65Ben Blanchard, “Duterte Aligns Philippines With China, Says U.S. Has Lost,” Reuters, October 20, 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-philippines/duterte-aligns-philippines-with-china-says-u-s-has-lost-idUSKCN12K0AS. Under his government, the Philippines has welcomed Chinese investment and become an enthusiastic partner in the Belt and Road Initiative.66Jason Gutierrez, “As Duterte Courts China, U.S. Says Don’t Forget Your Old Friend,” New York Times, July 16, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/16/world/asia/philippines-united-states-duterte.html; “Philippine Finance Chief Lauds China’s Belt and Road Initiative,” Xinhua Net, September 16, 2019, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-09/16/c_138396164.htm. A mere five years later, the nation was tilting back toward the United States, as Secretary of State Antony Blinken affirmed, as Secretary of State Mike Pompeo had before him, that Washington would come to the defense of the Philippines in the South China Sea if it were attacked.67Antony J. Blinken, “Fifth Anniversary of the Arbitral Tribunal Ruling on the South China Sea,” U.S. Department of State, July 11, 2021, https://www.state.gov/fifth-anniversary-of-the-arbitral-tribunal-ruling-on-the-south-china-sea/; Seth Robson, “Duterte Turns Philippines toward U.S. Again as His Term Ends and China Policy Sours,” Stars and Stripes, November 4, 2021, https://www.military.com/daily-news/2021/11/04/duterte-turns-philippines-toward-us-again-his-term-ends-and-china-policy-sours.html. Just like in the case of South Korea, we observe a situation in which the United States is arguably more eager to defend a country than that nation is to accept American help.

In 1992, U.S. personnel were expelled from the Philippines, after treaty negotiations in which the Americans offered $2 billion in aid broke down; the fact that the United States was the one offering to pay shows that it valued its military presence more than the Philippines did.68William Branigin, “U.S. Military Ends Role in Philippines,’ Washington Post, November 24, 1992, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1992/11/24/us-military-ends-role-in-philippines/a1be8c14-0681-44ab-b869-a6ee439727b7/. Compared to that nation, other American allies and partners in the region have been more hostile to China, particularly Japan and Taiwan. This does not appear to be the result of leverage that the United States has gained due to its military commitments, but because these states perceive more of a threat from China than do other countries in the Asia-Pacific. In fact, one of the East Asian countries most antagonistic to China has been Vietnam, a nation with which the United States has less friendly ties.69Sophia Yan, “Vietnam’s Defense Spending Is $5 Billion and Rising Fast,” CNN, May 23, 2016, https://money.cnn.com/2016/05/23/news/vietnam-military-spending/index.html. Vietnam has been hostile to Huawei and increased its military spending in recent years.70Raymond Zhong, “Is Huawei a Security Threat? Vietnam Isn’t Taking Any Chances,” New York Times, July 18, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/18/technology/huawei-ban-vietnam.html. Comparing its behavior with that of nations like South Korea and the Philippines highlights how irrelevant, or perhaps even counterproductive, U.S. military commitments have been to achieving geopolitical goals.

If countries know they can rely on the United States for defense, they have less reason than they otherwise would to worry about growing Chinese power and influence.

Why the U.S. military presence abroad does not translate into favorable political outcomes

It is easy to believe that the more military personnel and equipment a country has in a foreign nation, the more influence it has over that state; presence should translate into power. For most of history, this was true. Relying on this belief, American leaders justify the U.S. presence abroad by arguing that it helps achieve political and economic objectives. Their logic does not stand up to scrutiny.

The U.S. military presence in foreign countries does provide the ability to project military power—making it easier to fight wars and defend allies abroad. But that does not translate into political outcomes favorable to the United States when it seeks to influence allies and partners. Advocates of a strong American footprint overseas make broad claims, arguing that it contributes to U.S. power in a very general sense, including the ability to achieve goals related to economics or human rights. Yet America can better be described as a “Phantom Empire,” with the trappings and superficial signifiers of power rather than the actual ability to accomplish objectives.

The theory on which U.S. influence depends fails precisely because American elites are committed to maintaining a presence abroad. In order to exert leverage over the countries it has military alliances with, Washington must see its commitments as they really are—as costs, not benefits it should seek to maintain no matter what. Indeed, to the extent that American commitments allow nations to free-ride and underprovide for their own defense, they hinder the ability of the United States to accomplish geopolitical goals.71Baizhu Chen, Yi Feng, and Cyrus Masroori, “Collective Action in the Middle East? A Study of Free-Ride in Defense Spending,” Journal of Peace Research Volume 33, Issue 3 (1996): 323–339; William R. Gates and Katsuaki L. Terasawa, “Commitment, Threat Perceptions, and Expenditures in a Defense Alliance,” International Studies Quarterly Volume 36, Issue 1 (1992): 101–118. While many countries are willing to accept military support from the United States, in some cases American officials are more invested in an alliance than are the nations they are supposedly protecting. This indicates that ideology and domestic politics, more than vital interests or any sort of objective threat assessment, determine U.S. posture abroad.

Partners like Qatar and Saudi Arabia continue to frustrate American policymakers, with the U.S. presence in the Middle East giving leaders few levers to pull when seeking to change undesirable behavior. The same conceptual mistakes are being repeated in discussions about the rise of China, with many arguing for doubling down on military commitments in East Asia to preserve American influence. Yet if the past and present are any guide to the future, a strong U.S. military commitment is consistent with growing Chinese influence at American expense. Perhaps no country relies on the United States as much for defense as South Korea, yet it takes the side of Beijing on a wide variety of disputes. While an American military presence can potentially deter an invasion, countries decide the extent to which they want to accommodate growing Chinese power and influence based on their own perceived interests.

The existence of the American “Phantom Empire” provides an illusion of control and influence that does not exist, or exists for other reasons, like the ability to apply financial pressure. Except in the most extreme cases in which the United States threatens war, American influence is ultimately rooted in economic leverage, cultural affinity, and what has been called “soft power.”72Joseph S. Nye Jr., “Public Diplomacy and Soft Power,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science Volume 616, Issue 1 (2008): 94–109. Scholars write about the “Anglosphere,” a collection of nations tied to the United States and one another due to a shared heritage as members of the English-speaking community.73Srdjan Vucetic, The Anglosphere: A Genealogy of a Racialized Identity in International Relations (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2011). Where cultural affinity does not exist, American leaders can apply financial carrots and sticks, as during the Obama administration when the United States brought Myanmar out of its isolation and helped move it toward democracy, albeit temporarily.74Samuel Rubenfeld, “U.S. Formally Ends Sanctions on Myanmar,” Wall Street Journal, October 7, 2016, https://www.wsj.com/articles/BL-252B-11308. Seeking out trade agreements with nations as a way to preserve American influence, as was the intention behind the Trans-Pacific Partnership, is therefore a sound strategy, while a more militarized foreign policy is not. American ideals can spread through simply showing what works, the most important and clearest case of this being the series of events that eventually led to the collapse of the Soviet Union.75Stephen Kotkin, Armageddon Averted: The Soviet Collapse, 1970–2000 (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2008).

Military force can also be used to spread American influence when it can be threatened to be used against adversaries or when its protection is threatened to be withdrawn from friends or allies. The latter mechanism is theoretically possible, but rarely used by American policymakers, with President Trump’s threats against the Saudis and South Koreans being possible exceptions in recent years. Those who argue for any particular military presence abroad should explicitly articulate what they hope to achieve, not simply claim that troops translate into broad influence that can be put toward accomplishing American goals. Aside from maintaining the alliance or American presence itself, advocates of a more militarily assertive posture abroad must be asked, in each case, about their ultimate ends. Scaling back U.S. military commitments, investing in diplomacy, and putting resources toward domestic reform, particularly enacting policies related to improving technological innovation and economic growth, are the best ways to foster American influence across the world and ultimately yield favorable political outcomes.

On the current course, the coming decades will see increasing Chinese power and influence in East Asia.76Richard Hanania, “The Inevitable Rise of China: U.S. Options With Less Indo-Pacific Influence.” Given little indication that the United States is going to give up on its military commitments, one could imagine a world in the near future in which more countries behave like South Korea, free-riding off the U.S. military while tilting toward China on most economic and political matters. In extreme cases, countries may become “Finlandized” by China while nonetheless maintaining an American military presence. While such a situation may seem bizarre, all that it requires is a continuation of current trends, and Beijing’s influence should only grow in the coming decades. If that happens, it will be in part because U.S. policymakers, in their commitment to maintain current arrangements, mistook the illusion of power for the real thing.

Endnotes

- 1Gordon Lubold, Michael R. Gordon, and Andrew Jeong, “U.S., South Korea Near a Deal Over Cost of U.S. Forces on Peninsula,” Wall Street Journal, February 26, 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-south-korea-near-a-deal-over-cost-of-u-s-forces-on-peninsula-11614345296.

- 2“Chapter Six: Asia,” The Military Balance Volume 121, Issue 1 (2021), International Institute for Strategic Studies (London, IISS): 218–313.

- 3David P. Goldman, “South Korea Is the Pivot in the Huawei Wars,” Asia Times, May 30, 2020, https://asiatimes.com/2020/05/south-korea-is-the-pivot-in-the-huawei-wars/.

- 4Christian Davies, “South Korea Longs for Trump’s Focus as Efforts to Engage Pyongyang Stall,” Financial Times, November 21, 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/07ae391a-b48b-40c9-ad20-66488a7876d1.

- 5“Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy,” U.S. Department of Defense, accessed November 9, 2021, https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2018-National-Defense-Strategy-Summary.pdf.

- 6Hillary Clinton, “Remarks on the Obama Administration’s National Security Strategy,” U.S. Department of State, May 27, 2010, https://2009-2017.state.gov/secretary/20092013clinton/rm/2010/05/142312.htm.

- 7Jeffrey Hart, “Three Approaches to the Measurement of Power in International Relations,” International Organization Volume 30, Issue 2 (April 1976): 289–305.

- 8Paul Szoldra, “Trump’s Pentagon Quietly Made a Change to the Stated Mission It’s Had for Two Decades,” Task and Purpose, June 29, 2018, https://taskandpurpose.com/code-red-news/pentagon-mission.

- 9“Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy,” U.S. Department of Defense.

- 10Kathleen H. Hicks, Michael J. Green, and Heather A. Conley, “Donald Trump Doesn’t Understand the Value of U.S. Bases Overseas,” Foreign Policy, April 7, 2016, https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/04/07/donald-trump-doesnt-understand-the-value-of-u-s-bases-overseas/.

- 11Glenn Greenwald, “House Democrats, Working With Liz Cheney, Restrict Trump’s Planned Withdrawal of Troops from Afghanistan and Germany,” Intercept, July 2, 2020, https://theintercept.com/2020/07/02/house-democrats-working-with-liz-cheney-restrict-trumps-planned-withdrawal-of-troops-from-afghanistan-and-germany/; Keir Gils, “Real or Not, Trump’s Germany Withdrawal Helps Putin,” Chatham House, June 8, 2020, https://www.chathamhouse.org/expert/comment/real-or-not-trump-s-germany-withdrawal-helps-putin; Nic Robertson, “Trump’s Germany Troops Pullout May Be His Last Gift to Putin before the Election,” CNN, August 2, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/08/02/politics/trump-germany-troops-russia-intl/index.html.

- 12Joseph E. Fallon, “U.S. Geopolitics: Afghanistan and the Containment of China,” Small Wars Journal, July 12, 2013, https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/us-geopolitics-afghanistan-and-the-containment-of-china.

- 13Lindsey W. Ford and James Goldgeier, “Who Are America’s Allies and Are They Paying Their Fair Share of Defense?” Brookings Institution, December 17, 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/policy2020/votervital/who-are-americas-allies-and-are-they-paying-their-fair-share-of-defense/.

- 14Stephen G. Brooks, G. John Ikenberry, and William C. Wohlforth, “Don’t Come Home, America: The Case against Retrenchment,” International Security Volume 37, Issue 3 (2013): 7–51, 44–46.

- 15Daniel Egel, Adam R. Grissom, John P. Godges, Jennifer Kavanagh, and Howard J. Shatz, “Estimating the Value of Overseas Security Commitments,” RAND Corporation (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2016): 36.

- 16Brian L. Joiner, “Lurking Variables: Some Examples,” American Statistician Volume 35, Issue 4 (1981): 227–233.

- 17Andrew Gelman and Eric Loken, “The Statistical Crisis in Science: Data-Dependent Analysis—a ‘Garden of Forking Paths’—Explains Why Many Statistically Significant Comparisons Don’t Hold Up,” American Scientist Volume 102, Issue 6 (2014): 460–466.

- 18Other studies suffer from similar problems, as positive relationships between troop presence and favorable outcomes are always subject to the lurking variable problem. The problem with seeing troops as translating into influence and relying on such studies is that the proposed mechanism is very indirect and therefore uncertain. There is proposed a chain of causation in which there is some relationship between foreign bases and trade, and then trade leads to influence. For the argument to make sense, the effect in the first step of the chain, from troops to trade, would have to be large enough to influence the second step. In other words, the question is not whether more soldiers lead to greater trade, but whether that increase in trade is substantial enough to affect American influence, given all the other factors that influence how much trade flows from one country to another. After all, if the goal is to increase trade, then it could be more efficiently done through policies seeking that end, rather than having it be a byproduct of a policy built around deterrence and influence. Finding weak effects on trade or investment, even setting aside the lurking variable issue, is not enough to show a relationship between an American presence and an increase in U.S. power. The studies showing an impact of U.S. military presence on factors like trade and foreign direct investment do not even attempt to meet this standard. See Glen Biglaiser and Karl DeRouen Jr., “Following the Flag: Troop Deployment and U.S. Foreign Direct Investment,” International Studies Quarterly Volume 51, Issue 4 (2007): 835–854.

- 19Nicholas Bardsley, “Dictator Game Giving: Altruism or Artefact?” Experimental Economics Volume 11, Issue 2 (2008): 122–133.

- 20Veronica Stracqualursi, “Trump Apparently Threatens to Withdraw U.S. Troops from South Korea over Trade,” CNN, March 16, 2018, https://www.cnn.com/2018/03/15/politics/trump-us-troops-south-korea/index.html; Josh Dawsey, Damian Paletta, and Erica Werner, “In Fundraising Speech, Trump Says He Made up Trade Claim in Meeting with Justin Trudeau,” Washington Post, March 15, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-politics/wp/2018/03/14/in-fundraising-speech-trump-says-he-made-up-facts-in-meeting-with-justin-trudeau/.

- 21Choe Sang-Hun, “U.S. and South Korea Sign Deal on Shared Defense Costs,” New York Times, February 10, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/10/world/asia/us-south-korea-military-costs.html.

- 22Bob Woodward, Fear: Trump in the White House (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2018); John Bolton, The Room Where It Happened (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2020).

- 23Brett Samuels, “House Passes Resolution in Support of NATO by Unanimous Voice Vote,” Hill, July 11, 2018, https://thehill.com/homenews/house/396536-house-passes-resolution-in-support-of-nato-by-unanimous-voice-vote.

- 24Karoun Demirjian, “Senate Rebukes Trump’s Plan to Withdraw U.S. Forces from Syria, Afghanistan,” Washington Post, January 31, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/powerpost/senate-backs-mcconnells-rebuke-of-trumps-military-drawdown-plans-in-syria-afghanistan/2019/01/31/5812d058-2584-11e9-90cd-dedb0c92dc17_story.html; Catie Edmondson, “In Bipartisan Rebuke, House Majority Condemns Trump for Syria Withdrawal,” New York Times, October 16, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/16/us/politics/house-vote-trump-syria.html.

- 25Katie Bo Williams, “Outgoing Syria Envoy Admits Hiding US Troop Numbers; Praises Trump’s Mideast Record,” Defense One, November 12, 2020, https://www.defenseone.com/threats/2020/11/outgoing-syria-envoy-admits-hiding-us-troop-numbers-praises-trumps-mideast-record/170012/.

- 26Akbar Shahid Ahmed, “Mitch McConnell Is about to Doom One of Trump’s Attempts to ‘End Endless War,’” Huffington Post, September 18, 2020, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/trump-endless-wars-afghanistan_n_5f64e5b7c5b6b9795b1000bb.

- 27Jordan Tama, Joshua Busby, Craig Kafura, Joshua D. Kertzer, and Jonathan Monten, “Congress has NATO’s Back, Despite Trump’s Unilateralism,” Washington Post, April 3, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/04/03/congress-has-natos-back-despite-trumps-unilateralism/.

- 28Ben Rhodes, The World as It Is: A Memoir of the Obama White House (New York, NY: Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2019): 62–72.

- 29Joseph Simonson, “‘Our Alliances Will Be Completely Fractured’: Biden Claims ‘There Will Be No NATO’ If Trump Wins Second Term,” Washington Examiner, November 24, 2019, https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/news/our-alliances-will-be-completely-fractured-biden-claims-there-will-be-no-nato-if-trump-wins-second-term.

- 30“Military and Civilian Personnel by Service/Agency by State/Country, June 2021,” Defense Manpower Data Center, U.S. Department of Defense, accessed October 25, 2021, https://dwp.dmdc.osd.mil/dwp/api/download?fileName=DMDC_Website_Location_Report_2106.xlsx&groupName=milRegionCountry.

- 31“E.U. Restrictive Measures in Response to the Crisis in Ukraine,” European Council, Council of the European Union, accessed November 9, 2021, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/sanctions/ukraine-crisis/.

- 32Valerie Hopkins, Michael Peel, and Henry Fox, “Orban-Putin Talks Compound Disquiet over Hungary’s Russia Ties,” Financial Times, August 13, 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/9a1988e4-f8ff-11e9-a354-36acbbb0d9b6.

- 33Patrick Kingsley, “Hungary’s Leader Was Shunned by Obama, but Has a Friend in Trump,” New York Times, August 15, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/15/world/europe/hungary-us-orban-trump.html.

- 34Alexandra Gheciu, “NATO, Liberal Internationalism, and the Politics of Imagining the Western Security Community,” International Journal Volume 74, Issue 1 (2019): 32–46.

- 35Deborah Welch Larson, Origins of Containment: A Psychological Explanation (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1985).

- 36Humeyra Pamuk, “Turkey Should Scrap Russian Missile System or Face U.S. Sanctions: White House Official,” Reuters, November 10, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-turkey-security-usa/turkey-should-scrap-russian-missile-system-or-face-u-s-sanctions-white-house-official-idUSKBN1XK0JS.

- 37“Russia, Turkey Sign Deal for Supply of S-400 Missile Systems to Ankara,” Middle East Monitor, August 24, 2020, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20200824-russia-turkey-sign-deal-for-supply-of-s-400-missile-systems-to-ankara/; Amanda Macias, “U.S. Sanctions Turkey Over Purchase of Russian S-400 Missile System,” CNBC, December 15, 2020, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/12/14/us-sanctions-turkey-over-russian-s400.html.

- 38Mike Sweeney, “Reconsidering U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe,” Defense Priorities, September 14, 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/reconsidering-us-nuclear-weapons-in-europe; Charles Wald, “Pull U.S. Troops Out of Turkey: Former EUROCOM Deputy,” Breaking Defense, December 4, 2019, https://breakingdefense.com/2019/12/pull-us-troops-out-of-turkey-former-eucom-deputy/.

- 39Sebastian Schmidt, “Foreign Military Presence and the Changing Practice of Sovereignty: A Pragmatist Explanation of Norm Change,” American Political Science Review Volume 108, Issue 4 (2014): 817–829.

- 40G. John Ikenberry, After Victory: Institutions, Strategic Restraint, and the Rebuilding of Order after Major Wars (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2019).

- 41Mike Sweeney, “A Plan for U.S. Withdrawal from the Middle East,” Defense Priorities, December 21, 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/a-plan-for-us-withdrawal-from-the-middle-east.

- 42Christopher M. Blanchard, “Saudi Arabia: Background and U.S. Relations (RL33533),” Congressional Research Service, October 5, 2021, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL33533.

- 43Daniel DePetris, “End U.S. Support for War in Yemen,” Defense Priorities, December 8, 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/end-us-support-for-war-in-yemen; Mark Mazzetti and Eric Schmitt, “Quiet Support for Saudis Entangles U.S. in Yemen,” New York Times, March 13, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/14/world/middleeast/yemen-saudi-us.html.

- 44Ariane M. Tabatabai and Becca Wasser, “Could America Use Its Leverage to Alter the Saudis’ Behavior?” RAND Corporation, November 15, 2018, https://www.rand.org/blog/2018/11/could-america-use-its-leverage-to-alter-the-saudis.html.

- 45Amena Bakr, “Defying Allies, Qatar, Unlikely to Abandon Favor Syrian Rebels,” Reuters, March 20, 2014, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-syria-crisis-qatar/defying-allies-qatar-unlikely-to-abandon-favored-syria-rebels-idUSBREA2J0WM20140320.

- 46Adam Taylor, “As Trump Tries to End ‘Endless Wars,’ America’s Biggest Mideast Base Is Getting Bigger,” Washington Post, August 21, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/as-trump-tries-to-end-endless-wars-americas-biggest-mideast-base-is-getting-bigger/2019/08/20/47ac5854-bab4-11e9-8e83-4e6687e99814_story.html.

- 47Felicia Schwartz, “Trump Sides With Saudis, Other Gulf States in Rift With Qatar,” Wall Street Journal, June 6, 2017, https://www.wsj.com/articles/trump-says-in-tweet-he-discussed-qatar-with-arab-leaders-1496758326.

- 48“Iran Flies Food to Qatar amid Concerns of Shortages,” Reuters, June 11, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-gulf-qatar-iran-idUSKBN1920EG?il=0.

- 49“Iran Sends 1,100 Tonnes of Food to Qatar Daily: Report,” Gulf Times, June 23, 2017, https://www.gulf-times.com/story/554288/Iran-sends-1-100-tonnes-of-food-to-Qatar-daily-rep.

- 50Andrew Scott Cooper, The Oil Kings: How the U.S., Iran, and Saudi Arabia Changed the Balance of Power in the Middle East (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2012): 20, 202.

- 51Gregory Meyer, “U.S. Is Net Exporter of Oil for First Time in Decades,” Financial Times, November 29, 2019, https://www.ft.com/content/9cbba7b0-12dd-11ea-a7e6-62bf4f9e548a.

- 52Sam Meredith, “Who Will Blink First? What an All-Out Price War Means for the U.S., Saudi Arabia and Russia,” CNBC, March 9, 2020, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/03/09/oil-prices-what-a-price-war-means-for-the-us-saudi-arabia-and-russia.html. The motivations of various actors are murky. According to at least one report, it was Russia that initiated the production increases with the aim of harming U.S. oil producers. See Illya Arkhipov, Will Kennedy, Olga Tanas, and Grant Smith, “Putin Dumps MBS to Start a War on America’s Shale Industry,” Bloomberg Quint, March 9, 2020, https://www.bloombergquint.com/business/putin-dumps-mbs-to-start-a-war-on-america-s-shale-oil-industry. Yet it was Saudi Arabia that initiated the “price war” in response. See Anjli Raval, David Sheppard, and Derek Brower, “Saudi Arabia Launches Oil Price War after Russia Deal Collapse,” Financial Times, March 8, 2020, https://www.ft.com/content/d700b71a-6122-11ea-b3f3-fe4680ea68b5. The extent to which either country was motivated by a desire to harm the U.S. oil industry is therefore unclear.

- 53Timothy Gardner, Steve Holland, Dmitry Zhdannikov, and Rania El Gamal, “Special Report: Trump Told Saudi: Cut Oil Supply or Lose U.S. Military Support–Sources,” Reuters, April 30, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-global-oil-trump-saudi-specialreport/special-report-trump-told-saudi-cut-oil-supply-or-lose-u-s-military-support-sources-idUSKBN22C1V4.

- 54Rania El Gamal, Olesya Astakhova, and Alex Lawler, “Saudi, Russia Agree Oil Cuts Extension, Raise Pressure for Compliance,” Reuters, June 3, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-oil-opec/saudi-russia-agree-oil-cuts-extension-raise-pressure-for-compliance-idUSKBN23A1OU.

- 55Gregor Aisch, Josh Keller, and K.K. Rebecca Lai, “The World According to China,” New York Times, July 24, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/07/24/business/international/the-world-according-to-china-investment-maps.html.

- 56For a report on this, based on leaked cables from the Iranian government, see Tim Arango, James Risen, Farnaz Fassihi, Ronen Bergman, and Murtaza Hussain, “The Iran Cables: Secret Documents Show How Tehran Wields Power in Iraq,” New York Times, November 19, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/11/18/world/middleeast/iran-iraq-spy-cables.html.

- 57Michael Doran and Peter Rough, “China’s Emerging Middle Eastern Kingdom,” Tablet, August 2, 2020, https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/israel-middle-east/articles/china-middle-eastern-kingdom; Robert D. Kaplan, “Beijing Fills the Mideast Vacuum,” Wall Street Journal, January 20, 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/beijing-fills-the-mideast-vacuum-11611183756.

- 58For a skeptical take on the idea of whether the U.S. actually implemented this strategy, see Michal Kolmaš and Šárka Kolmašová, “A ‘Pivot’ That Never Existed: America’s Asian Strategy under Obama and Trump,” Cambridge Review of International Affairs Volume 32, Issue 1 (2019): 61–79.

- 59Richard Hanania, “The Inevitable Rise of China: U.S. Options With Less Indo-Pacific Influence,” Defense Priorities, May 26, 2021, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/the-inevitable-rise-of-china.

- 60John Hemmings and Sunghim Cho, “South Korea’s Growing 5G Dilemma,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, July 7, 2020, https://www.csis.org/analysis/south-koreas-growing-5g-dilemma.

- 61Bob Woodward, Fear: 305.

- 62Alexandra Hutzler, “Learning Donald Trump Needed to Be Reminded of World War 3 Threat Was Most ‘Illuminating’ Part of Book: Woodward,” Newsweek, September 11, 2018, https://www.newsweek.com/donald-trump-world-war-3-woodward-1115426.

- 63Song Su-Hyun, “Korean Tech Industry Braces for New U.S. Sanction on Huawei,” Korea Herald, September 10, 2020, http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20200910000782; Tae-jun Kang, “On Hong Kong, South Korea Is Caught between China and U.S.,” Diplomat, May 29, 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2020/05/on-hong-kong-south-korea-is-caught-between-china-and-us/; Jane Perlez, “China Creates a World Bank of Its Own and the U.S. Balks,” New York Times, December 4, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/05/business/international/china-creates-an-asian-bank-as-the-us-stands-aloof.html.

- 64Uri Friedman, “How to Choose Between the U.S. and China? It’s Not That Easy,” Atlantic, July 26, 2019, https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2019/07/south-korea-china-united-states-dilemma/594850/.

- 65Ben Blanchard, “Duterte Aligns Philippines With China, Says U.S. Has Lost,” Reuters, October 20, 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-philippines/duterte-aligns-philippines-with-china-says-u-s-has-lost-idUSKCN12K0AS.

- 66Jason Gutierrez, “As Duterte Courts China, U.S. Says Don’t Forget Your Old Friend,” New York Times, July 16, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/16/world/asia/philippines-united-states-duterte.html; “Philippine Finance Chief Lauds China’s Belt and Road Initiative,” Xinhua Net, September 16, 2019, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-09/16/c_138396164.htm.

- 67Antony J. Blinken, “Fifth Anniversary of the Arbitral Tribunal Ruling on the South China Sea,” U.S. Department of State, July 11, 2021, https://www.state.gov/fifth-anniversary-of-the-arbitral-tribunal-ruling-on-the-south-china-sea/; Seth Robson, “Duterte Turns Philippines toward U.S. Again as His Term Ends and China Policy Sours,” Stars and Stripes, November 4, 2021, https://www.military.com/daily-news/2021/11/04/duterte-turns-philippines-toward-us-again-his-term-ends-and-china-policy-sours.html.

- 68William Branigin, “U.S. Military Ends Role in Philippines,’ Washington Post, November 24, 1992, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1992/11/24/us-military-ends-role-in-philippines/a1be8c14-0681-44ab-b869-a6ee439727b7/.

- 69Sophia Yan, “Vietnam’s Defense Spending Is $5 Billion and Rising Fast,” CNN, May 23, 2016, https://money.cnn.com/2016/05/23/news/vietnam-military-spending/index.html.

- 70Raymond Zhong, “Is Huawei a Security Threat? Vietnam Isn’t Taking Any Chances,” New York Times, July 18, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/18/technology/huawei-ban-vietnam.html.

- 71Baizhu Chen, Yi Feng, and Cyrus Masroori, “Collective Action in the Middle East? A Study of Free-Ride in Defense Spending,” Journal of Peace Research Volume 33, Issue 3 (1996): 323–339; William R. Gates and Katsuaki L. Terasawa, “Commitment, Threat Perceptions, and Expenditures in a Defense Alliance,” International Studies Quarterly Volume 36, Issue 1 (1992): 101–118.

- 72Joseph S. Nye Jr., “Public Diplomacy and Soft Power,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science Volume 616, Issue 1 (2008): 94–109.

- 73Srdjan Vucetic, The Anglosphere: A Genealogy of a Racialized Identity in International Relations (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2011).

- 74Samuel Rubenfeld, “U.S. Formally Ends Sanctions on Myanmar,” Wall Street Journal, October 7, 2016, https://www.wsj.com/articles/BL-252B-11308.

- 75Stephen Kotkin, Armageddon Averted: The Soviet Collapse, 1970–2000 (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2008).

- 76Richard Hanania, “The Inevitable Rise of China: U.S. Options With Less Indo-Pacific Influence.”

More on Middle East

Featuring Jennifer Kavanagh

August 28, 2025

Featuring Jennifer Kavanagh

July 30, 2025

Featuring Rosemary Kelanic

July 30, 2025

By Dan Caldwell

July 28, 2025

Events on Grand strategy