July 12, 2023

Neutrality not NATO: Assessing security options for Ukraine

Key points

- The United States should not guarantee Ukraine’s security, whether via the NATO alliance or some lesser means.

- Guaranteeing Ukraine’s security serves no major U.S. interest and would increase the risk of a U.S. or NATO war with Russia and nuclear escalation.

- Those dangers are why the United States refuses to fight directly for Ukraine against Russia today, and they would induce similar caution if the United States guaranteed Ukraine’s security. Lacking a major interest, U.S. promises to defend Ukraine will be unserious and unbelievable.

- Fake security guarantees for Ukraine might have some deterrent value, despite their lack of credibility, given the terrible risks involved for Russia in testing those promises. However, fake security guarantees would likely degrade Ukraine’s security on balance, both by preserving a cause of the war and by encouraging Ukrainian leaders to make dangerous choices based on the false prospect of U.S. protection.

- Announcing plans to guarantee Ukraine’s security once the war ends would encourage Russia to continue fighting. Guaranteeing Ukraine’s security now would demand a choice between ignoring the commitment and undermining other U.S. security guarantees or fighting for Ukraine and sparking an immediate nuclear crisis.

- What the United States can credibly offer Ukraine is armed neutrality, where the United States, ideally with European allies taking the lead, provides Ukraine with arms and training without security guarantees.

Security guarantees for Ukraine would create insecurity

The United States will not guarantee Ukraine’s security, but it might pretend to. The dangers of fighting Russia for Ukraine are so severe—entailing a real prospect of nuclear war—and the benefits so lacking, that commitments to defend Ukraine will be unserious and unbelievable. Paper pledges do not obviate interests and allow states to believably threaten suicidal mass destruction for no good reason. Whether they prefer putting Ukraine in NATO or some other sort of pledge, what advocates of guaranteeing Ukraine’s security suggest is an obvious bluff—a fraud.

These false promises for Ukraine might give Russia some pause if it considers invading Ukraine again. Even a very low chance of nuclear war induces caution. But U.S. security guarantees will likely damage Ukraine’s security overall by antagonizing Russia, preserving a cause of the war, and encouraging Ukraine to take risks in expectation of help that will not come. Additionally, false promises to defend Ukraine might merely remind everyone that other U.S. alliance commitments are similarly suspect.

Like most states, Ukraine must ultimately secure itself, as it has been impressively doing during the current war. The United States and especially its European allies should continue to fund, arm, and train Ukraine’s armed forces. Armed neutrality, not making Ukraine a permanent U.S. security dependent, should be the U.S. goal.1This paper is about U.S. foreign policy. So, while it makes arguments that tend to apply to other countries, such as about the challenges of credibility threatening to defend a country you have refused to defend, it does not explicitly prescribe policy for them.

Why offer Ukraine protection?

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 popularized the idea of putting Ukraine in NATO, or as an alternative option, protecting it through various bilateral arrangements. These proposals come from think tanks in Europe and the United States, former officials, and various European leaders, particularly in the Baltics, the United Kingdom, and Poland. Because most of these proposals entail “security guarantees,” it is useful to briefly explore what this means.

Here a security guarantee is defined as it is generally understood: one state’s formal agreement to use force to defend another if it is attacked. Merely promising arms or to sanction aggression does not qualify. That could be labelled as something less—such as a security assurance.

That said, there is no universally recognized definition of a security guarantee. Leaders sometimes use the term to mean acts short of war. Even NATO’s collective defense pledge, Article 5, which is widely discussed as a pledge to fight, in fact says only that each ally “will take the actions it deems necessary to assist the Ally attacked,” not that every ally will necessarily go to war to defend it.2“The North Atlantic Treaty,” April 4, 1949, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/official_texts_17120.htm. Despite this text, this paper treats NATO membership as entailing security guarantees because it is broadly interpreted as a pledge to make war.

The history of NATO suggests states nonetheless see the Article 5 pledge as something more: as a threat by the United States not just to make war, but to use nuclear weapons to defend allies. The alliance started at a time when the United States had recently used nuclear weapons against Japan and also perceived a conventional disadvantage in trying to defend NATO allies against the Soviet Union.3The balance of power was more favorable to the United States than it generally seemed then. Matthew A. Evangelista, “Stalin’s Postwar Army Reappraised” International Security 7, No. 3 (Winter 1982–1983): 110–38. The Eisenhower administration, wary of trying to match Soviet manpower in Europe, saw nuclear weapons as a relatively affordable way to address this problem.4David Alan Rosenberg, “The Origins of Overkill: Nuclear Weapons and American Strategy, 1945–1960,” International Security 7, no. 1 (Spring 1983): 3–71; Glenn H. Snyder, “The New Look of 1953,” in Strategy, Politics and Defense Budgets, eds. Warner R. Schilling, Paul Y. Hammond, and Glenn H. Snyder (New York: Columbia University Press, 1962), pp. 393–437. The “New Look” or “massive retaliation” strategy thus threatened to use nuclear weapons against attacking Soviet Forces—”first use” in nuclear vernacular.5The White House, “Basic National Security Policy,” October 30, 1953, https://irp.fas.org/offdocs/nsc-hst/nsc-162-2.pdf.

Despite the emergence of a Soviet arsenal sufficient to make mass destruction mutual if the United States used its nuclear weapons and major changes in U.S. nuclear weapons doctrine, the threat to use nuclear weapons first remains a key pillar of U.S. alliance commitments.6On the evolution of U.S. doctrine see Austin Long, Deterrence – From Cold War to Long War: Lessons from Six Decades of RAND Research (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2008), https://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG636.html; Fred Kaplan, Wizards of Armageddon (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1991). That U.S. threat underpins NATO—it is what members most value.7Henry D. Sokolski ed., Getting MAD: Nuclear Mutual Assured Destruction, Its Origins and Practice (Carlisle, PA: US Army War College Press, 2004), 107. U.S. tactical nuclear weapons remain in Europe to make that threat more credible.8Jonathan Masters and Will Merrow, “Nuclear Weapons in Europe: Mapping U.S. and Russian Deployments,” Council on Foreign Relations, March 30, 2023, https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/nuclear-weapons-europe-mapping-us-and-russian-deployments.

This history and the policies it informs mean that putting Ukraine in NATO entails a threat to start a nuclear war with Russia. Offering a non-NATO, bilateral U.S. security guarantee to Ukraine, that is, a promise to forcefully defend it, carries a similar threat—which is why it is so coveted by Kyiv. By design, U.S. pledges to defend allies threaten to resort to nuclear war.

There are various proposals for how the United States and its allies should protect Ukraine:

- The most aggressive option is to put Ukraine in NATO now, regardless of whether Ukraine remains partly occupied by Russia or at war. Ukrainian leaders, who seek maximum outside support, prefer this option, as it would seem to entail NATO countries directly joining them in combat with Russia.9Andriy Zagorodnyuk, “To Protect Europe, Let Ukraine Join NATO—Right Now,” Foreign Affairs, June 1, 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/ukraine/protect-europe-let-ukraine-join-nato-right-now; Paul Poast, “It’s Time to Bring Ukraine into NATO,” World Politics Review, June 9, 2023, https://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/nato-membership-ukraine-russia-war-putin-zelensky/.

- The most common proposal is to allow Ukraine to join NATO once the war ends, perhaps as part of a peace plan.10Ukraine has reportedly reconciled themselves this after long advocating for more immediate admission. Daniel Boffey, “Ukraine Defence Minister Expects NATO Guarantee After War,” Guardian, June 28, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/jun/28/ukraine-defence-minister-expects-nato-guarantee-after-war.

- A similar alternative favored by more avowedly progressive voices is to offer Ukraine a series of bilateral security guarantees as part of a brokered settlement.11Lise Morjé Howard and Michael O’Hanlon, “The Case for a Security Guarantee for Ukraine,” Foreign Affairs, March 20, 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/ukraine/nato-membership-case-security-guarantee-ukraine. Even the withdrawn Congressional Progressive Caucus Letter, controversial for being insufficiently pro-Ukraine, endorsed this option. Alexander Ward et al., “House Progressives Retract Russia-Diplomacy Letter Amid Dem Firestorm,” Politico, October 25, 2022, https://www.politico.com/news/2022/10/25/house-progressives-russia-diplomacy-00063338. These guarantees in theory could come from a variety of nations, but Ukraine is naturally most interested in U.S. promises.

- Those who want Ukraine in NATO but see it politically difficult at present advocate looser security guarantees of some sort now, with a transition to NATO membership at some future point.12Kitty Donaldson, “Sunak Says NATO Should Make Ukraine Security Pledge by July,” Bloomberg, February 18, 2023, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-02-18/sunak-nato-ukraine-security-guarantee-should-be-agreed-by-july; “Poland, Czech Republic and Slovakia Call for Security Guarantees for Ukraine Even Before NATO Membership,” Ukrainska Pravda, April 24, 2023, https://www.pravda.com.ua/eng/news/2023/04/24/7399224/; Judy Dempsey, “Why Ukraine Needs Security Guarantees,” Carnegie Europe, April 18, 2023, https://carnegieeurope.eu/strategiceurope/89557; Liana Fix, “The Future is Now: Security Guarantees for Ukraine,” Survival 65, no. 3 (June 2023): 67–72, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00396338.2023.2218697. Ukrainian officials have proposed a plan of this ilk, labelled the Kyiv Security Compact. President of Ukraine, “The Kyiv Security Compact,” September 13, 2023, https://www.president.gov.ua/storage/j-files-storage/01/15/89/41fd0ec2d72259a561313370cee1be6e_1663050954.pdf.

- Finally, there are proposals for security commitments that fall short of guarantees, typically meaning commitments to arm and train Ukraine; this is often called the “Israel Model.”13For a dissection of these proposals see Emma Ashford and Kelly A. Grieco, “The Promise and Pitfalls of an ‘Israel Model’ for Ukraine,” Stimson Center, July 5, 2023, https://www.stimson.org/2023/red-cell-the-promise-and-pitfalls-of-an-israel-model-for-ukraine/. A partial list of these proposals is found in Rajan Menon, “How to End the War in Ukraine,” Boston Review, April 26, 2023, https://www.bostonreview.net/forum/how-to-end-the-war-in-ukraine/; Eric Ciaramella, “Envisioning a Long-Term Security Guarantee for Ukraine, June 8, 2023 (Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2023), https://carnegieendowment.org/2023/06/08/envisioning-long-term-security-arrangement-for-ukraine-pub-89909. Some authors confusingly label this option as a security guarantee, but it does not meet the definition used here. Commitments to arm and train Ukraine are consistent with its neutrality.14To be sure, who is neutral is somewhat in the eye of the beholder, as there no common definition of what it means to be neutral between parties not at war, like NATO and Russia, as opposed to remaining neutral in relation to an ongoing conflict. On the meaning of neutrality in the latter context see Oona A. Hathaway and Scott Shapiro, “Supplying Arms to Ukraine is Not an Act of War,” Just Security, March 12, 2022, https://www.justsecurity.org/80661/supplying-arms-to-ukraine-is-not-an-act-of-war/. But it is reasonable to say you are neutral until you are part of a military alliance opposed to the state in question.

The safest, most credible option for Ukraine is the fifth. Several mistaken assumptions underlie the other four types of proposals. The first assumption, usually left implicit, is that the security of the United States and its allies depend on Ukraine’s.15For a good refutation of these arguments see Joshua Shifrinson, “American Interests in the Ukraine War,” Defense Priorities, September 14, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/american-interests-in-the-ukraine-war. Second, these proposals tend to assume U.S. credibility is created by treaties or promises—that deterrence is easy to extend—and Ukraine can easily enter the long list of nations for which the United States provides deterrence by threatening nuclear war with Russia. Third, it is often assumed the United States and its allies must induce Ukraine to make peace, especially if it is sacrificing some territory to de facto Russian control, and that Ukraine will never cut such a deal without security guarantees.16Steven Erlanger, “What Does It Mean to Provide ‘Security Guarantees’ to Ukraine?” New York Times, January 10, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/10/world/europe/ukraine-russia-security-guarantees.html.

As shown below, all these assumptions are wrong. U.S. security is almost entirely independent of Ukraine’s—unless it is degraded by promising to defend Ukraine. Credibility is difficult to extend, and in this case essentially impossible—as it would involve threatening nuclear war for a state whose safety does not benefit ours. Finally, it is neither clear why the United States should approach Ukraine as a supplicant to get it to make peace, nor why dubious promises, as opposed to the continued provision of arms, training, and funds, would be needed for that.

U.S. security does not depend on Ukraine’s

Western sympathy understandably lies with Ukraine in its defensive war with Russia. In 2014 and 2022, Russia attacked Ukraine, a smaller, weaker state that is somewhat democratic (certainly more so than Russia), and lawlessly seized its territory. Russia has fired missiles at civilian targets and committed additional war crimes.17“Ukraine: Apparent War Crimes in Russia-Controlled Areas,” Human Rights Watch, April 3, 2022, https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/04/03/ukraine-apparent-war-crimes-russia-controlled-areas. Law, morality, and ideological affinity drive U.S. support for Ukraine.

It makes sense for U.S. foreign policy and funds to follow U.S. popular sentiment, to a point. But this is a moral or charitable project, not a security one, which is a reason why U.S. support for Ukraine, while quite generous (more than $113 billion in 2022), is circumscribed to avoid direct U.S. combat with Russia.18“Congress Approved $113 Billion of Aid to Ukraine in 2022,” Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, January 5, 2023, https://www.crfb.org/blogs/congress-approved-113-billion-aid-ukraine-2022. U.S. foreign policy can be quite ideological and crusading, but risking a nuclear war for ideology, a sense of justice, or democratic solidarity is a bridge too far for just about everyone.

Of course, few advocates of supporting Ukraine admit they are doing charity.19Many advocates of extending security guarantees to Ukraine do not bother to justify their proposal in U.S. security terms beyond arguing that it will deter Russia and protect Ukraine. They assume that Ukrainian and U.S. interests are the same. On the differences between U.S. and Ukrainian interests sese Patrick Porter, Justin Logan, and Benjamin H. Friedman, “We’re Not All Ukrainians Now,” Politico Europe, May 17, 2022, https://www.politico.eu/article/ukraine-russia-war-nato-eu-us-alliance-solidarity/. It is typical in U.S. foreign policy for presidents and other national leaders to “oversell” their preferred foreign policy to appeal to audiences and constituencies with various rationales.20Theodore Lowi, “Making Democracy Safe for the World: Foreign Policy and National Politics,” in Domestic Sources of Foreign Policy, ed. James N. Rosenau (New York: Free Press, 1967), 295–331. Taxpayers are not eager to spend billions, let alone risk war without a security payoff. So, the more costly and risky an aspect of U.S. foreign policy is, the more it is sold as a vital security project.21Justin Logan and Benjamin H. Friedman, “The Case for Getting Rid of the National Security Strategy,” War on the Rocks, November 4, 2022, https://warontherocks.com/2022/11/the-case-for-getting-rid-of-the-national-security-strategy/; Ben Friedman, “Biden is Exaggerating the Stakes of Ukraine,” UnHerd, June 3, 2022, https://unherd.com/thepost/joe-biden-is-exaggerating-the-security-stakes-of-ukraine/.

There are two major arguments for the idea that U.S. security depends on Ukraine. One is that Russia will use Ukraine as a launching pad for further aggression. The second says the global norm of territorial integrity is important to U.S. security and dependent on Ukraine winning its war. Basically, one says Ukraine losing will lead to further Russian aggression, and the other says it will lead to aggression by other countries elsewhere. The failures of these arguments are laid out below.

Ukraine is not a launchpad for Russian empire

The major way analysts try to tie Ukraine’s security to the United States’ security is by arguing that Russian control of Ukraine would enable further aggression. This argument relies on a misreading of Russian intent and capability.

Russian leaders might well prefer to have the Soviet empire back, but seeing the war in Ukraine as a first step toward that mission is a mistake. Russian concern about Ukraine is unique, even among its neighbors. As a parade of U.S. diplomats and officials have noted, Russia has historically sought to keep Ukraine aligned with, or at least not hostile to, Moscow, not necessarily to rule it directly.22Christopher McCallion, “Assessing Liberal and Realist Explanations for the Russo-Ukrainian War” Defense Priorities, June 7, 2023, http://defensepriorities.org/explainers/assessing-realist-and-liberal-explanations-for-the-russo-ukrainian-war. That means preventing it from joining Western security institutions, particularly NATO.23Samir Puri, Russia’s Road to War with Ukraine: Invasion Amidst the Ashes of Empires (London: Biteback Publishing, 2022), 79–106. The same seems to go for Belarus, Georgia, and perhaps Kazakhstan, but Ukraine for historical and geographic reasons seems the “brightest of all redlines” for Moscow as William J. Burns, then U.S. ambassador to Russia and current CIA director, put it in 2008.24William J. Burns, The Back Channel: A Memoir of American Diplomacy and the Case for Its Renewal (New York, Random House, 2019), 233. Russia’s invasions in both 2014 and 2022 fit this reading. This is not to say Russia had legitimate security reasons to attack Ukraine, but that its longstanding concern made the attack predictable.25John J. Mearsheimer, “Why the Ukraine Crisis Is the West’s Fault: The Liberal Delusions That Provoked Putin” Foreign Affairs 93, no. 5 (September/October 2014): 77–89. Powerful states are reliably “neuralgic” about hostile alliances on their border. See Stephen Van Evera, “To Prevent War and Secure Ukraine, Make Ukraine Neutral,” Defense Priorities, February 19, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/to-prevent-war-and-secure-ukraine-make-ukraine-neutral.

As for capability, many analysts seem to believe Ukraine is a strategic prize that would empower Russia if fully conquered.26“Amb. Michael McFaul: U.S. Has ‘a Major Strategic Interest to Help the Ukrainians Win the Battle of Donbas’,” MSNBC, April 20, 2022, https://www.msnbc.com/andrea-mitchell-reports/watch/amb-michael-mcfaul-u-s-has-a-major-strategic-interest-to-help-the-ukrainians-win-the-battle-of-donbas-138149445774; Atlantic Council, “Why Ukraine’s Success is in the U.S. National Interest,” video, YouTube, February 4, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K6OUQe_Za18. See also “Russia’s War in Ukraine: How Does it End?” Council on Foreign Relations, May 31, 2022, https://www.cfr.org/event/russias-war-ukraine-how-does-it-end. See also Alina Polyakova and Daniel Fried, “Putin’s Long Game in Ukraine,” Foreign Affairs, February 23, 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/ukraine/2022-02-23/putins-long-game-ukraine. This analysis is often based on a shaky interpretation of the start of World War II—the notion that appeasing Nazi Germany merely fueled its further aggression. Besides misreading Britain’s rationale for appeasement at the Munich conference, this view misses the key differences between Nazi Germany then and Russia now. The former was a military juggernaut developing the capacity to conquer much of Europe, and Czechoslovakia was additive to their balance of power advantage.

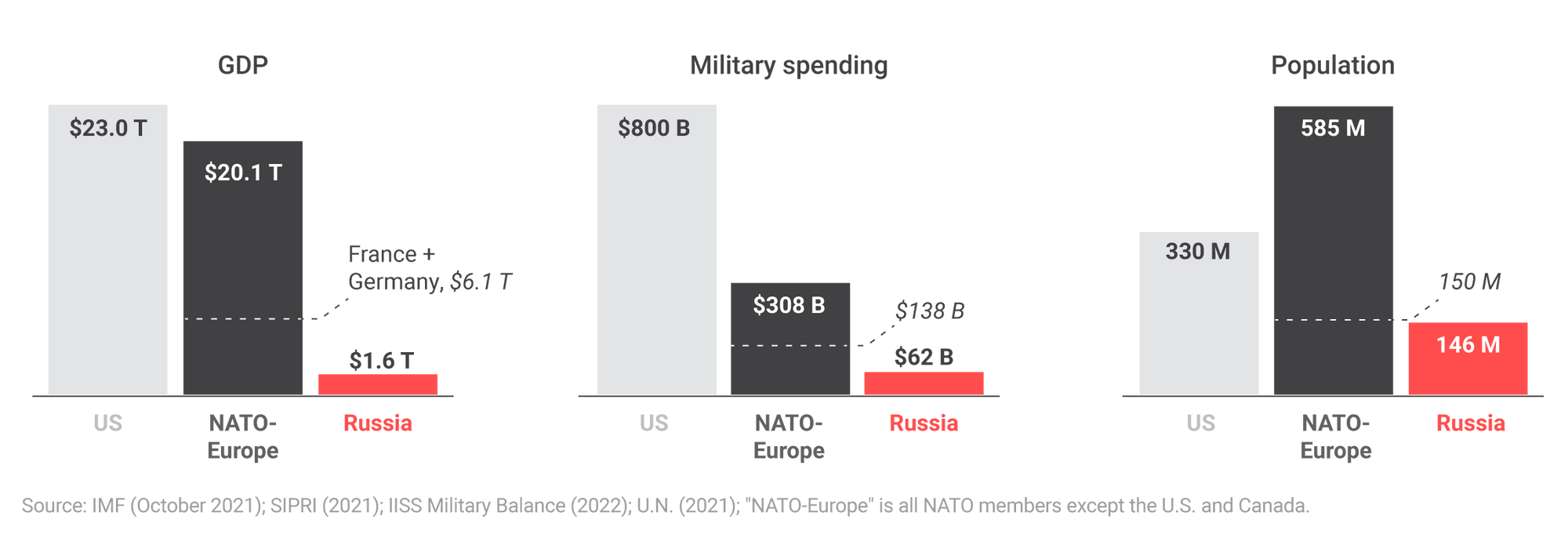

Taking Ukraine, by contrast, does little for Russia’s capability to further aggress. Of course, holding Ukraine would help geographically if the target were Poland or Moldova. But even that is far from a direct threat to the United States. In any case, there is no great store of latent power in Ukraine that Russia could harness to its war machine. Ukraine’s prewar gross domestic product (GDP) of $200 billion, even if could simply be added to Russia’s, would still leave it at less than $2 trillion, a far cry from the European Union’s $17 trillion.27“GDP (Current US$) – Ukraine, Russian Federation, European Union,” World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=UA-RU-EU. Charitably adding Russia’s informal ally of Belarus and adjusting for purchasing power, the triumvirate would still possess about one-third of the EU’s GDP.28“GDP, PPP (Current International $) – Russian Federation, Belarus, Ukraine, European Union,” World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.PP.CD?locations=RU-BY-UA-EU.

The U.S. vs. NATO-Europe vs. Russia along three common measures of power

As events demonstrate, for Russia, Ukraine is more of a strategic trap than a springboard to further conquest. With a pre-war population of 44 million, whose nationalism Russian aggression enflamed, the cost to Russia of conquering and pacifying Ukraine is far larger than any benefit it might gain by exploiting material riches.29Stephen Van Evera, “Hypotheses on Nationalism and War,” International Security 18, no. 4 (Spring 1994): 5–39. And now that Russia has run aground in Ukraine, displaying shocking military failures, there is even less reason to see Ukraine’s defense as necessary to protect Poland or other nearby NATO states.30Those states naturally want a U.S. ensured buffer, but the Russian weakness on display should lower fears of Russian, not raise them. Benjamin H. Friedman and Justin Logan, “Europe Can Stand on Its Own. The Ukraine Invasion Proves It.” Week, March 20, 2022, https://theweek.com/russo-ukrainian-war/1011475/europe-can-stand-on-its-own-the-ukraine-invasion-proves-it; Stephen Wertheim, “Europe is Showing That It Could Lead Its Own Defense,” Washington Post, March 3, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2022/03/03/europe-defense-nato-ukraine-war/. Furthermore, the defensive advantages Ukraine has exploited, albeit largely with the help of U.S. and Western European technology, seem to make conquest harder than it was in the early or mid-twentieth century, cutting against the case that more U.S. help is needed to hold off Russia.31Leonid Bershidsky, “War in Ukraine So Far Favors the Defense,” Japan Times, June 14, 2023, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2023/06/14/commentary/world-commentary/russia-ukraine-war-6/; Frank Hoffman, “American Defense Priorities after Ukraine,” War on the Rocks, January 2, 2023, https://warontherocks.com/2023/01/american-defense-priorities-after-ukraine/.

In this vein, it is notable how advocates of defending Ukraine compare it to postwar Germany, noting they were both divided and under occupation.32Steven Erlanger, “If a Divided Germany Could Enter NATO, Why Not Ukraine?” New York Times, May 26, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/26/world/europe/ukraine-nato-germany.html. “Why not then include Ukraine in NATO, as West Germany was?” this thinking goes. What is left out of this formulation is the security rationale for the United States: how West Germany’s independence was key to maintaining a balance of the power in the Cold War due to its central geography, its industrial might that would enrich the Soviet Union if conquered, and the likelihood it would develop nuclear weapons and trigger another world war if not defended.33Marc Trachtenberg, A Constructed Peace: The Making of the European Settlement, 1945-1963 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999), 95–145. By comparison, Ukraine is strategically unimportant.

Ukraine has already protected the norm of territorial integrity

The other argument pinning U.S. security to Ukraine’s says that allowing Ukraine to fall prey to Russia would show that states can violate sovereignty with impunity and create a wave of global aggression.34

Johan Hassel, Kate Donald, and Laura Kilbury, “Why the United States Must Stay the Course on Ukraine,” Center for American Progress, February 22, 2023, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/why-the-united-states-must-stay-the-course-on-ukraine/; Joseph R. Biden Jr., “President Biden: What America Will and Will Not Do in Ukraine,” New York Times, May 31, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/31/opinion/biden-ukraine-strategy.html; Quoted in Robin Wright, “Ukraine is Now America’s War, Too,” New Yorker, May 1, 2022, https://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/ukraine-is-now-americas-war-too. See also Marc A. Thiessen, “If Putin is Allowed to Invade Ukraine, America’s Credibility Would Lie in Tatters,” Washington Post, February 8, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2022/02/08/ukraine-russia-war-united-states-china/; Robert C. O’Brien, “How to Teach Beijing a Lesson in Ukraine,” Foreign Policy, September 1, 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/09/01/china-taiwan-ukraine-war-lessons/?tpcc=recirc_latest062921;

Antony J. Blinken, “Secretary Blinken’s Press Availability,” U.S. Department of State, March 4, 2022, https://www.state.gov/secretary-antony-j-blinken-at-a-press-availability-15/. The norm of territorial integrity, in other words, is a such a stabilizing (and fragile) force that the United States must forcibly defend it.35Mark W. Zacher, “The Territorial Integrity Norm: International Boundaries and the Use of Force,” International Organization 55, no. 2 (Spring 2001): 215–250.

This argument suffers from terrible flaws. For one, the United States, with nuclear weapons, docile neighbors, and ocean barriers, is so secure, as are its key allies, that it is not clear that a norm of territorial integrity matters much to U.S. security, even though it may be important globally. Further, it is doubtful states aggress due to the health of a global norm, rather than their peculiar local circumstances and perceived interests. China’s decision about whether to invade Taiwan, for example, will likely turn on China’s nationalistic feelings, the balance of capability, the politics of Taiwan, and probably the odds of U.S. intervention, far more than whether Russia gets away with taking a part of Ukraine or China’s overall assessment of the health of the territorial integrity norm.

To the extent the norm is important, what matters to its health is whether Russia’s example seems worth emulating, not whether Russia gains any Ukrainian territory or never attacks again.36Samuel Charap and Miranda Priebe, “Avoiding a Long War: U.S. Policy and the Trajectory of the Russia-Ukraine Conflict,” Rand Corporation January 2023, https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PEA2510-1.html. Even in the best-case scenario for Russia from here on out, Russia’s invasion will be perceived globally more as warning against the perils of aggression than a success worth imitating. Russia has suffered terribly for invading Ukraine, due to broad sanctions and especially the pain of the war. It has displayed why modern military technology and nationalism serve the territorial status quo. The norm of territorial integrity is in good shape due to the difficulties of conquest, whatever promises the United States makes to Ukraine.37On the decline of interstate war and reduced benefits of conquest see, John Mueller, “Retreat from Doomsday: The Obsolescence of Major War (New York: Basic Books, 1989); 321–328; Carl Kaysen, “Is War Obsolete? A Review Essay,” International Security 14, no. 4 (Spring 1990): 42–64; Stephen Van Evera, “Primed for Peace: Europe After the Cold War,” International Security 15, no. 3 (Winter 1990–91): 7–57.

How promising to defend Ukraine erodes U.S. security

Promising to fight for Ukraine would not enhance U.S. security. Such promises would instead undermine U.S. security for the obvious reason that they rely on threatening a war that could escalate to mass nuclear destruction.

True, as discussed below, U.S. threats to make war for Ukraine, and especially to escalate to nuclear war, would not be credible. But that does not mean they would be cost-free. Even if peace held, the United States would be promising to secure a 1,200-mile land border with Russia. That would be expensive and require substantial manpower to be stationed in Ukraine, if taken seriously. After all, for all its defensive success, Ukraine could not stop Russia’s seizure of Crimea in 2014 or broad advances in 2022. This manpower, like other U.S. capabilities dedicated to Ukraine, would not be available for other contingencies more important to U.S. security.

Ukraine’s land border with Russia

Security guarantees would increase the risk of war. There would always be those who would insist the United States take its promise to defend Ukraine seriously. After all, a small but prominent group of Americans wants the United States to be at war with Russia today.38“Open Letter Calling for Limited No Fly Zone,” Politico, March 8, 2022, https://www.politico.com/f/?id=0000017f-6668-ddc5-a17f-f66d48630000. Even a conventional war with Russia in Ukraine would be a nearly unprecedented security disaster for the United States. After all, Russia would have far more at stake, including perhaps its independence, and thus should be expected to fight hard despite its conventional deficiencies. Further, given the profound consequences, even a small chance of nuclear war should be given a wide berth. And in this case, the odds would hardly be small.

In sum, by guaranteeing Ukraine’s security, the United States would degrade its own. It would gain no tangible benefit and take a terrible risk. As much as the United States has unwisely expanded its alliances, extending them to Ukraine would be an act of unprecedented recklessness.

U.S. security guarantees to Ukraine will not be credible

Discussion about expanding NATO to Ukraine and other nations often takes U.S. credibility to go to war for the ally as a given. It is assumed that because the Article 5 pledges have never really been tested by state aggression that the deterrent threats underlying the alliance are inviolate.

But this idea, that extended deterrence comes easy, is at odds with history and the field of strategic studies, which matured in the early Cold War. Much important scholarship, including Thomas Schelling’s masterwork, Arms and Influence, was an effort to understand how one could credibly threaten to fight a war for an ally in a condition of mutually assured destruction.39Thomas Schelling, Arms and Influence (New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press, 2008). Scholars offered an array of answers to this question—tripwire forces, counterforce nuclear targeting, battlefield nuclear weapons, and “flexible response.”40On the continuation of plans to strike first in U.S. nuclear planning into the present see, Benjamin H. Friedman, Christopher A. Preble, and Matt Fay, “The End of Overkill? Reassessing U.S. Nuclear Weapons Policy, Cato Institute White Paper, September 24, 2013, https://www.cato.org/white-paper/end-overkill-reassessing-us-nuclear-weapons-policy. But they universally saw it as a difficult problem. And this concerned a time and place, Western Europe in the early Cold War, where the stakes seemed high. The European allies, despite their relatively high importance to the United States, required all manner of reassurance during the Cold War—U.S. bases, nominal control over locally-based nuclear weapons, or in the cases of France and the United Kingdom, their own nuclear weapons. In Ukraine, U.S. stakes are far lower.

Threats to fight wars, which alliance commitments entail, become credible when states have the capability to carry them out and demonstrable, strong interests in doing so.41Daryl Press, Calculating Credibility: How Leaders Assess Military Threats (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2007), 8–28. With respect to securing Ukraine, the United States has problems on both fronts. While U.S. military capability to help Ukraine is clearly impressive, Ukraine’s long border with Russia poses serious challenges. The U.S. has the capability to defend it, but it would be costly to do so, especially in terms of opportunity cost.

More importantly, the United States has no vital security interests in Ukraine, as discussed, whereas Russia has far stronger interests, demonstrated by its willingness to wage war. This asymmetry, combined with Russia’s nuclear weapons, makes it inherently not credible for the United States to commit to defend Ukraine.

Having refused to fight for Ukraine when its independence was at stake due to Russia’s invasion, the United States cannot easily convince observers that it will fight next time. Putting Ukraine in NATO or otherwise promising to defend it does not magically create a U.S. interest worth risking a nuclear war for.

Advocates of offering to protect Ukraine sometimes argue that U.S. credibility problems actually aid their case. Because the U.S. threats to defend the other 30 NATO members would suffer if it did not defend Ukraine, it must do so to preserve the whole alliance structure, this logic goes.42Benjamin Tallis, “Security Guarantees for Ukraine,” German Council on Foreign Relations June 30, 2023, https://dgap.org/en/research/publications/security-guarantees-ukraine-0. And Russia knows this, so it will be deterred.

The main problem with this thinking is its assumption the Kremlin buys into the same mythology about credibility domino theories. It seems more likely Russians think like leaders normally do and will focus on material U.S. interests that justify taking terrible risks for Ukraine, or the lack thereof.43Friedman, Preble, and Fay, The End of Overkill? It is difficult to convince people you will fight a war where you lack strong interests in order to show them you will do so when you have stronger interests. You are asking them to believe you are deranged.

Since U.S. promises to fight for Ukraine will not be credible, they will likely be irrelevant to preventing wars, like the 1994 Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances.44“Memorandum on Security Assurances,” December 5, 1994, https://policymemos.hks.harvard.edu/files/policymemos/files/2-23-22_ukraine-the_budapest_memo.pdf?m=1645824948. That agreement is often billed as a promise of U.S. (and other nations’) protection for Ukraine in exchange for its agreement to relinquish nuclear weapons. However, it only amounted to a promise to not invade Ukraine and complain at the United Nations if someone did. Like the Budapest Memorandum, a new promise to defend Ukraine could amount to great diplomatic sound and fury, signifying nothing.

That said, the credibility challenge undermining any U.S. commitment to defend Ukraine, phony though it may be, could create several new dangers. One is that a future leader might do something rash, like try to fix the problem by deploying tripwire U.S. forces to the Donbass, making war with Russia and nuclear escalation far more likely.

A second danger in attempting to extend deterrence to Ukraine is that the naked fraud will simply remind rivals that other U.S. commitments are similarly dubious.45On the idea that may U.S. security commitments during the Cold War were bluffs see Marc Trachtenberg, “Robert Jervis and the Nuclear Question,” University of California, Los Angeles, December 22, 2011, https://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/polisci/faculty/trachtenberg/cv/Jervis(34a).doc. After all, the U.S. commitment to defend the Baltic states is also unattached to any strong material interest. Although this is probably not news to the Russians, and their failure to invade the Baltics is likely due to other factors than NATO, the net result would be to make an attack testing a U.S. alliance a bit more likely.

A third danger of handing out a fake defensive promise is that the recipient alone might believe in them or believe in them enough to get into trouble. This possibility, which is not hypothetical, is discussed below.

Pretending to protect Ukraine is bad for Ukraine’s security

Extending security guarantees to Ukraine may prove counterproductive, heightening its troubles. One reason for this is a kind of moral hazard, where Ukraine takes risks because of protective promises it mistakenly takes as real.46This is sort of moral hazard, a concept from insurance where the beneficiary takes risks because the insurer bears the cost of the risk. On U.S. protection encouraging moral hazard, or “reckless driving” among allies and other potentially protected parties, see Barry R. Posen, Restraint: A New Foundation for U.S. Grand Strategy (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2014), 65–67; Alan J. Kuperman, “Mitigating the Moral Hazard of Humanitarian Intervention: Lessons from Economics,” Global Governance 14, no. 2 (Spring 2008): 219–224. Ukraine’s circumstance is somewhat different, because thinks it does not bear the risk when it actually does. It is like buying fake insurance. On this point see Benjamin H. Friedman, “Biden Doesn’t Like Russia’s Meddling in Ukraine. But He’s Not Prepared to Stop It.” NBC, May 6, 2021, https://www.nbcnews.com/think/opinion/biden-doesn-t-russia-s-meddling-ukraine-he-s-not-ncna1266535; Natalie Armbruster and Benjamin H. Friedman, “Who is an Ally, and Why Does it Matter?,” Defense Priorities, October 12, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/who-is-an-ally-and-why-does-it-matter. Another reason is that security guarantees may prolong the war or heighten the risk of its resumption.

Before elaborating on these points, it is worth replying to one likely objection: that Ukraine surely knows better than American analysts what is good for it. The response is simple: Ukraine is after real protection, not protection theater, which is what it is likely to get from the United States. Furthermore, we should not rule out the possibility that they are mistaken just because we sympathize with their plight.

Phony U.S. protection invites bad choices

Desperate circumstances and understandingly nationalistic politics make Ukraine’s leaders eager for any security solution that is not territorial compromise with Russia, and they might be willing to overlook their seeming protector’s limited commitment.47Robert Jervis, Perception and Misperception in International Politics: New Edition (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2017), 120–122. Thus, they might eschew a possible negotiated settlement that involves territorial sacrifice while the war continues based on the idea that an impending U.S. commitment will eventually improve their negotiating position. Or, if they receive NATO membership or a security guarantee after the war ends, they may suffer from a false sense of security, and misread the dangers of taking various risks vis-à-vis Russia.

Something similar occurred before the war, contributing to the conditions that caused it. U.S. leaders deliberately created the impression in Ukraine that it was a sort of quasi-ally subject to some military protection, at least in the future. As noted, with the Budapest Memorandum, U.S. leaders gave Ukraine the impression that it might be protected by the United States even though no real commitment had been made. At the Bucharest Summit in 2008, the Bush administration convinced the alliance to support Ukraine’s (and Georgia’s) eventual accession to NATO membership, though without offering a membership action plan.

Ever since, NATO’s position has been that it has an “open door” to Ukraine’s eventual membership. Ukraine became a NATO “Enhanced Opportunities Partner” in 2020, and in November 2021, just before Russia’s invasion, the United States and Ukraine signed a “Charter on Strategic Partnership” which gave U.S. backing to Ukraine’s war aims, including regaining Crimea.48U.S. Department of State, “U.S.-Ukraine Charter on Strategic Partnership,” November 10, 2021, https://www.state.gov/u-s-ukraine-charter-on-strategic-partnership/. When Russia began a buildup of troops on Ukraine’s border in 2021, the Biden administration repeatedly emphasized its “unwavering” and “ironclad” support for Ukraine’s sovereignty and refused to rule out its eventual NATO entry.49Michael Crowley, “Blinken Will Visit Ukraine in Show of Support Against Russia,” New York Times, April 30, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/30/us/politics/blinken-biden-ukraine-russia.html; Matthias Williams, “Ukraine’s Yermak Assured of “Ironclad” U.S. Support in Call With Sullivan—Tweet,” Reuters, November 26, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/ukraines-yermak-assured-ironclad-us-support-call-with-sullivan-tweet-2021-11-26/; Jim Garamone, “Defense Secretary Says U.S. Commitment to NATO Defense ‘Ironclad,’” U.S. Department of Defense, February 17, 2022, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/2938530/defense-secretary-says-us-commitment-to-nato-defense-ironclad/. U.S. aid and joint exercises, both of which increased after 2014, also likely enhanced Ukraine’s belief, or hope, that they enjoyed a degree of U.S. protection.50W.J. Hennigan, “Obama Approves $75 Million in Nonlethal Aid to Ukraine,” Los Angeles Times, March 11, 2015, https://www.latimes.com/world/europe/la-fg-us-ukraine-aid-20150311-story.html.

All this effort to imply a kind of commitment to Ukraine, a sort of strategic ambiguity, could have discouraged Ukraine to cut a deal with Russia to remain neutral before the war.51Mike Sweeney, “Saying ‘No’ to NATO: Options for Ukrainian Neutrality,” Defense Priorities, August 12, 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/saying-no-to-nato-options-for-ukrainian-neutrality; Van Evera, “To Prevent War and Secure Ukraine, Make Ukraine Neutral.” Similarly, a Ukraine more evidently on its own might have gone further to implement the Minsk II accords, a key Russian demand before the war.52Stephen Bryen, “War Looms as U.S. and Kiev Ignore Minsk II Protocols,” Asia Times, February 21, 2022, https://asiatimes.com/2022/02/war-looms-as-us-and-kiev-ignore-minsk-ii-protocols.

It is possible Ukraine would have done nothing differently absent all this theatrical support from Washington. Their nationalistic anger at Russia for attacking it in 2014 likely made compromise politically difficult, if not impossible. But the false promise of U.S. protection at least encouraged the uncompromising side of Ukrainian politics. Being unclear about how far it would go to defend Ukraine was irresponsible behavior by Washington, which courted moral hazard, if it did not cause it.

Some will object that this amounts to blaming the victim. But causal weight and blame are different things. A fixation with fairness is often inappropriate or unhelpful in international politics. Safety, not someone’s idea of fairness, is what states have good reason to seek.53Kenneth Waltz, Theory of International Politics (Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, Inc., 2010). Saying Ukraine is innocent of aggression and Russia is guilty is true but unhelpful to Ukraine’s security, let alone U.S. security. What matters is that Ukraine failed to secure itself which, given its geography, required compromising with Russia. And U.S. policy encouraged that failure.

Guaranteeing more war?

The more obvious reason security guarantees may ironically erode Ukraine’s security is that their prospect helped cause the war and therefore formally issuing them may also help prolong it. This is a controversial but fundamental point: if you believe the war was merely due to a failure to credibly promise to defend Ukraine and that such credibility is easily attained, you will take a different view. But the weight of the evidence says the prospect of Ukraine getting Western protection was an important cause of war, if not a sufficient one.54Puri, Russia’s Road to War with Ukraine.

This is not to justify the invasion or suggest it resulted due to legitimate security concerns. It is rather to note that Ukraine joining NATO, or getting NATO’s protection less formally, was a Russian “red line,” as so many officials and scholars warned.55Burns, The Back Channel, 233; Thomas L. Friedman, “Now a Word from X,” New York Times, May 2, 1998, https://www.nytimes.com/1998/05/02/opinion/foreign-affairs-now-a-word-from-x.html. It strengthened Russia’s desire to forcibly seek to control Ukraine, particularly Crimea, to keep it out of the Western sphere.56Puri, Russia’s Road to War with Ukraine, 255–256.

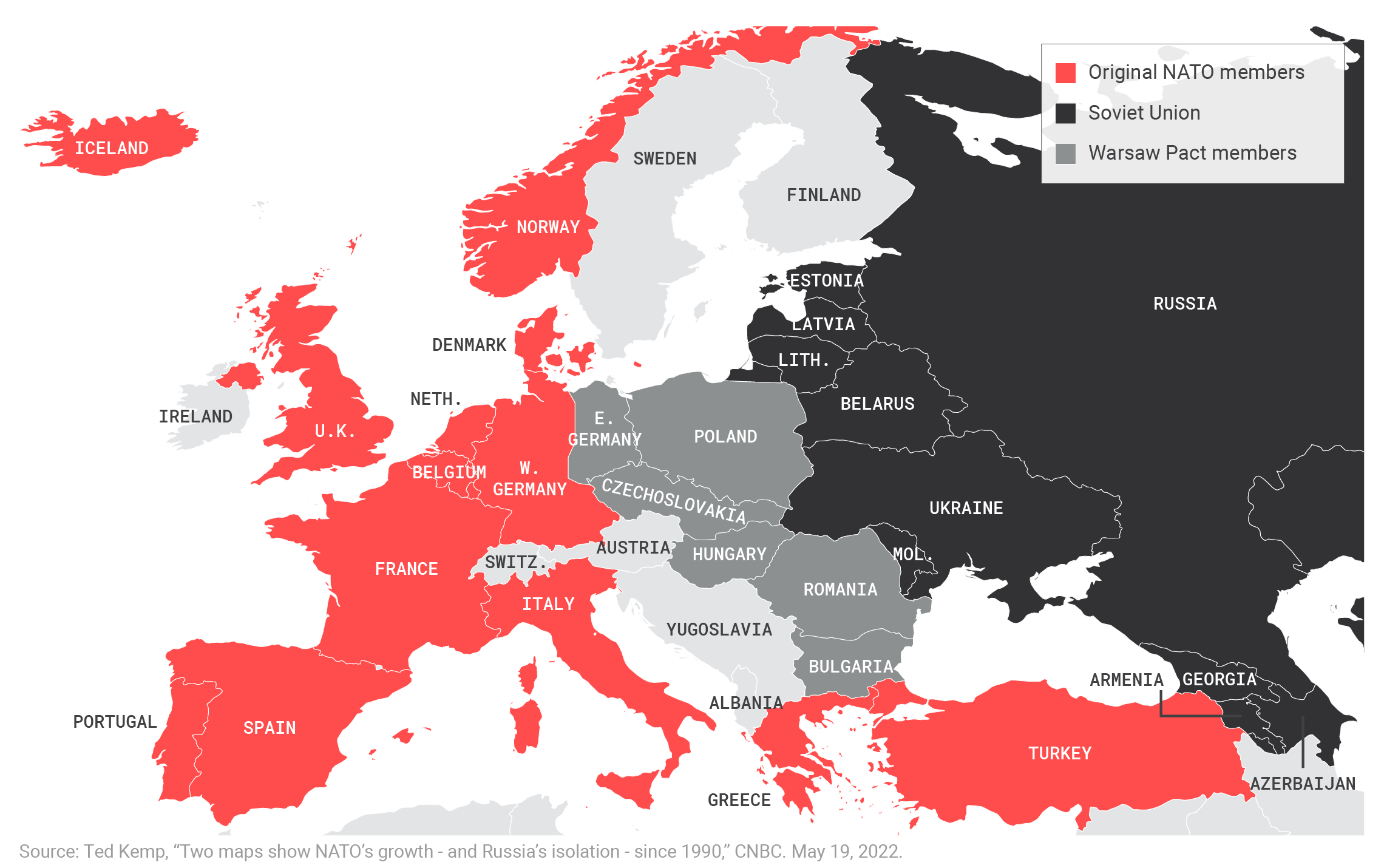

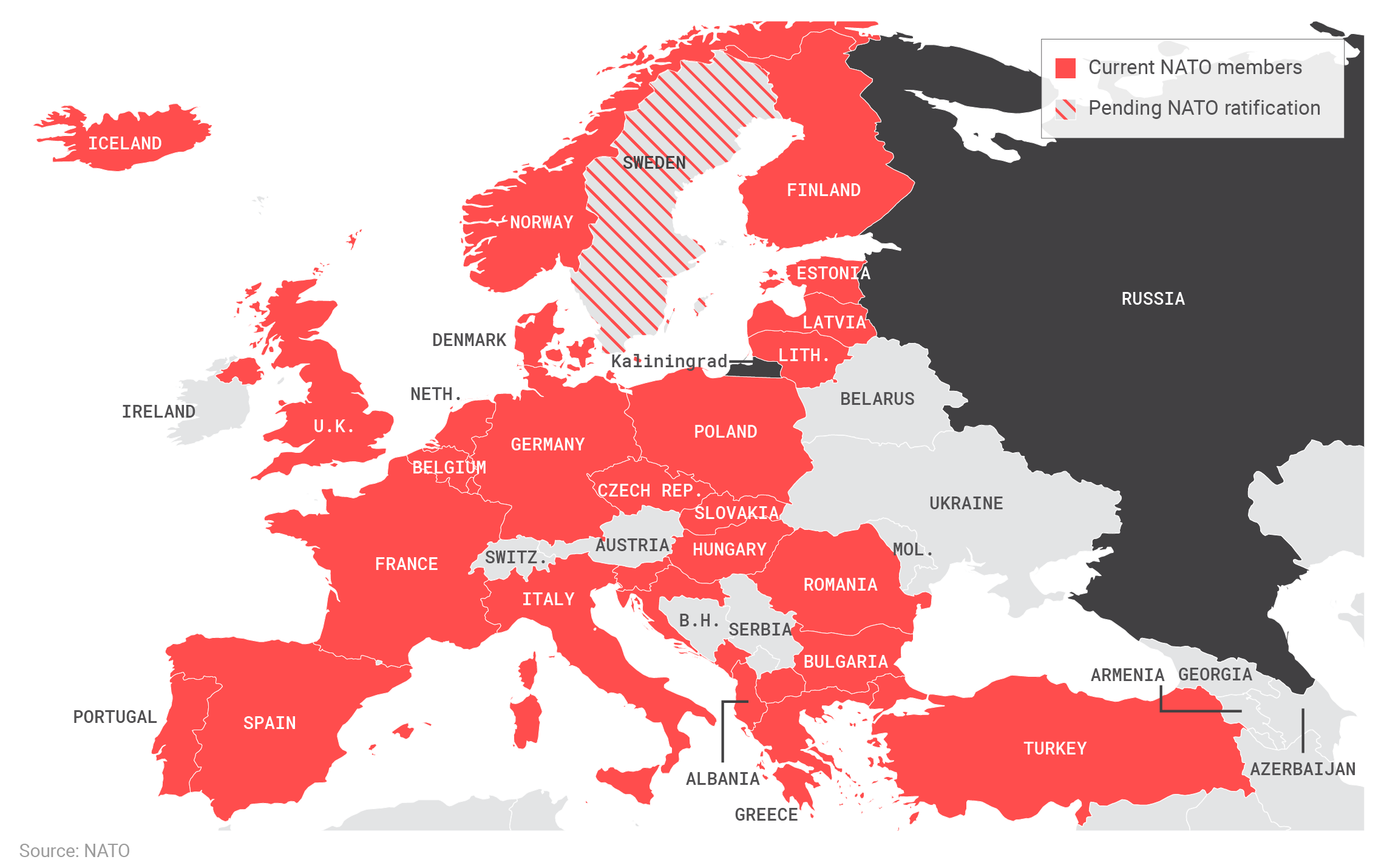

Europe’s major military alliances in 1990 (left) vs. 2023 (right)

Since 1990, even as the Soviet Union dissolved along with the Warsaw Pact, NATO (in red) has expanded and now includes several states that share borders with Russia.

The prospect of security guarantees for Ukraine seems to be a reason Russia invaded, though hardly the only one. Both Russian rhetoric and the timing of the attack suggest as much.57McCallion, “Assessing Liberal and Realist Explanations for the Russo-Ukrainian War.” U.S. policy toward Ukraine made the war predictable (and predicted)—not justified.58Van Evera, “To Prevent War and Secure Ukraine, Make Ukraine Neutral.” Here it is worth noting that if the United States and its allies want to end the war, even informally, they need both Russia and Ukraine. The insistence by advocates of security guarantees that the United States needs to offer them to placate Ukraine in a peace deal is odd, since that would make Russia likely to refuse any deal. U.S. sympathy with Ukraine and a desire for peace should not make Washington Ukraine’s supplicant in peace talks, sacrificing its own interest to win Kyiv’s assent.

By extending security guarantees to Ukraine, Washington would preserve a grievance that helped spark the war. And that would make the war harder to end. Or if the guarantees came after peace, they would make peace harder to maintain. Note that saying Ukraine can only join NATO once the war ends gives Russia a strong reason to continue the war. Putting it in NATO now, by contrast, would force the alliance to choose: do nothing despite its Article 5 commitment to Ukraine or act in Ukraine’s defense and spark an immediate nuclear crisis.

Armed neutrality: a safer and credible alternative

What the United States should offer Ukraine rather than security guarantees is armed neutrality—give Ukraine no promised protection but instead provide arms and training so Ukraine can defend itself. The idea is to drive up the already considerable cost to Russia of attacking Ukraine again in a credible and sustainable way, one that avoids unjustified risks.

The advantages of armed neutrality over security guarantees are several. First, while arming Ukraine has been expensive, doing so indefinitely should require considerably lower annual costs than the current rate, as Ukraine should be able to maintain the capability it has gained without an infusion of more than $100 billion annually. Nor would armed neutrality involve great security risk to Americans. Russia has shown it will not escalate against the United States for arming Ukraine—which makes sense, as that could be suicidal. The United States and Russia have achieved a rough modus vivendi that involves considerable acrimony over Ukraine but sharp limits on mutual danger. Armed neutrality might leave relations in a troubled state, but they would not make them worse.

Second, offering Ukraine armed neutrality, unlike security guarantees, is credible. Rather than promising something—fighting for Ukraine—the U.S. has failed to do for sensible fears of escalation, this option means continuing to do something that has already safely occurred. True, public support for Ukraine might ebb, and continuing the current annual support over $100 billion would be excessive and unlikely. But the U.S. desire to arm Ukraine will likely remain robust for some time.

Third, armed neutrality is unlikely to trigger further attacks from Russia. Russia would surely be angered by the provision of arms indefinitely and might see this as a soft extension of Western security institutions to Ukraine, which is dangerous in the same sense as security guarantees, only less so.59Andrew Cheatham, “Is ‘Neutralization’ Obsolete After the Ukraine War?” United States Institute of Peace, June 2, 2022, https://www.usip.org/publications/2022/06/neutralization-obsolete-after-ukraine-war. But the “neutrality” part of the equation should limit Russian angst and help keep the peace, along with deterrence.

Two caveats are in order. First, the tendency to try to placate Ukraine and domestic U.S. audiences by labelling arms transfer and training as a kind of security guarantee should be resisted. As noted, this prospect is dangerous and not credible. It could anger Russia, encourage Kyiv to believe it has more real protection than it does, and excite U.S. credibility hawks into pretending real U.S. promises were on the line, making actual steps toward war more likely. That said, dangers would be limited because Russia should recognize these are guarantees in name only, labelled that way for obvious political reasons.

Second, the United States should not make minimum pledge requirements individually, as recent reports suggest may occur.60Guy Chazan and Henry Foy, “Western Allies Plan to Provide Long-Term Security Assurance to Ukraine,” Financial Times, June 14, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/8f0528ba-45a4-42c0-b099-07a34e2ee9ff. With or without armed neutrality, the United States should shift the burdens of European security to European states, as it is their backyard and security more directly at stake, and they are more than capable of defending themselves against Russia with less U.S. help.61As noted, the Russia’s poor military performance in the war strengthens the case for European strategic autonomy and other terms for European states developing greater collective military capability without the United States. Mike Sweeney, “How Would Europe Defend Itself?,” Defense Priorities, April 11, 2023, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/how-would-europe-defend-itself. Overall pledges from NATO which allow the U.S. to reduce its share of Ukraine’s support costs over time are more sensible. The states now calling for NATO membership for Ukraine should be willing to bear a greater share of future military aid and, eventually, reconstruction.

Ukraine, like most states at most times, must protect itself. That is the reality events have revealed. Since Ukraine has the misfortune of sharing a border and much political history with Russia, its security inevitably depends on reaching some accommodation with Russia, using some mix of deterrence and diplomacy. Attempting to make Ukraine a U.S. protectorate will not change that.

Ukraine can succeed in securing itself; there is a reason Ukraine went a quarter of a century without being attacked by Russia after the Cold War. Russian weakness revealed by the war shows this task is easier than previously thought. Counting on the United States or other allies to fight is understandable but dangerously naive. Counting on their beneficence, while working to build long-term self-sufficiency and a diplomatic path to prolonged peace, is more sensible, credible, and much safer.

Endnotes

- 1This paper is about U.S. foreign policy. So, while it makes arguments that tend to apply to other countries, such as about the challenges of credibility threatening to defend a country you have refused to defend, it does not explicitly prescribe policy for them.

- 2“The North Atlantic Treaty,” April 4, 1949, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/official_texts_17120.htm. Despite this text, this paper treats NATO membership as entailing security guarantees because it is broadly interpreted as a pledge to make war.

- 3The balance of power was more favorable to the United States than it generally seemed then. Matthew A. Evangelista, “Stalin’s Postwar Army Reappraised” International Security 7, No. 3 (Winter 1982–1983): 110–38.

- 4David Alan Rosenberg, “The Origins of Overkill: Nuclear Weapons and American Strategy, 1945–1960,” International Security 7, no. 1 (Spring 1983): 3–71; Glenn H. Snyder, “The New Look of 1953,” in Strategy, Politics and Defense Budgets, eds. Warner R. Schilling, Paul Y. Hammond, and Glenn H. Snyder (New York: Columbia University Press, 1962), pp. 393–437.

- 5The White House, “Basic National Security Policy,” October 30, 1953, https://irp.fas.org/offdocs/nsc-hst/nsc-162-2.pdf.

- 6On the evolution of U.S. doctrine see Austin Long, Deterrence – From Cold War to Long War: Lessons from Six Decades of RAND Research (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2008), https://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG636.html; Fred Kaplan, Wizards of Armageddon (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1991).

- 7Henry D. Sokolski ed., Getting MAD: Nuclear Mutual Assured Destruction, Its Origins and Practice (Carlisle, PA: US Army War College Press, 2004), 107.

- 8Jonathan Masters and Will Merrow, “Nuclear Weapons in Europe: Mapping U.S. and Russian Deployments,” Council on Foreign Relations, March 30, 2023, https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/nuclear-weapons-europe-mapping-us-and-russian-deployments.

- 9Andriy Zagorodnyuk, “To Protect Europe, Let Ukraine Join NATO—Right Now,” Foreign Affairs, June 1, 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/ukraine/protect-europe-let-ukraine-join-nato-right-now; Paul Poast, “It’s Time to Bring Ukraine into NATO,” World Politics Review, June 9, 2023, https://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/nato-membership-ukraine-russia-war-putin-zelensky/.

- 10Ukraine has reportedly reconciled themselves this after long advocating for more immediate admission. Daniel Boffey, “Ukraine Defence Minister Expects NATO Guarantee After War,” Guardian, June 28, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/jun/28/ukraine-defence-minister-expects-nato-guarantee-after-war.

- 11Lise Morjé Howard and Michael O’Hanlon, “The Case for a Security Guarantee for Ukraine,” Foreign Affairs, March 20, 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/ukraine/nato-membership-case-security-guarantee-ukraine. Even the withdrawn Congressional Progressive Caucus Letter, controversial for being insufficiently pro-Ukraine, endorsed this option. Alexander Ward et al., “House Progressives Retract Russia-Diplomacy Letter Amid Dem Firestorm,” Politico, October 25, 2022, https://www.politico.com/news/2022/10/25/house-progressives-russia-diplomacy-00063338.

- 12Kitty Donaldson, “Sunak Says NATO Should Make Ukraine Security Pledge by July,” Bloomberg, February 18, 2023, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-02-18/sunak-nato-ukraine-security-guarantee-should-be-agreed-by-july; “Poland, Czech Republic and Slovakia Call for Security Guarantees for Ukraine Even Before NATO Membership,” Ukrainska Pravda, April 24, 2023, https://www.pravda.com.ua/eng/news/2023/04/24/7399224/; Judy Dempsey, “Why Ukraine Needs Security Guarantees,” Carnegie Europe, April 18, 2023, https://carnegieeurope.eu/strategiceurope/89557; Liana Fix, “The Future is Now: Security Guarantees for Ukraine,” Survival 65, no. 3 (June 2023): 67–72, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00396338.2023.2218697. Ukrainian officials have proposed a plan of this ilk, labelled the Kyiv Security Compact. President of Ukraine, “The Kyiv Security Compact,” September 13, 2023, https://www.president.gov.ua/storage/j-files-storage/01/15/89/41fd0ec2d72259a561313370cee1be6e_1663050954.pdf.

- 13For a dissection of these proposals see Emma Ashford and Kelly A. Grieco, “The Promise and Pitfalls of an ‘Israel Model’ for Ukraine,” Stimson Center, July 5, 2023, https://www.stimson.org/2023/red-cell-the-promise-and-pitfalls-of-an-israel-model-for-ukraine/. A partial list of these proposals is found in Rajan Menon, “How to End the War in Ukraine,” Boston Review, April 26, 2023, https://www.bostonreview.net/forum/how-to-end-the-war-in-ukraine/; Eric Ciaramella, “Envisioning a Long-Term Security Guarantee for Ukraine, June 8, 2023 (Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2023), https://carnegieendowment.org/2023/06/08/envisioning-long-term-security-arrangement-for-ukraine-pub-89909.

- 14To be sure, who is neutral is somewhat in the eye of the beholder, as there no common definition of what it means to be neutral between parties not at war, like NATO and Russia, as opposed to remaining neutral in relation to an ongoing conflict. On the meaning of neutrality in the latter context see Oona A. Hathaway and Scott Shapiro, “Supplying Arms to Ukraine is Not an Act of War,” Just Security, March 12, 2022, https://www.justsecurity.org/80661/supplying-arms-to-ukraine-is-not-an-act-of-war/. But it is reasonable to say you are neutral until you are part of a military alliance opposed to the state in question.

- 15For a good refutation of these arguments see Joshua Shifrinson, “American Interests in the Ukraine War,” Defense Priorities, September 14, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/american-interests-in-the-ukraine-war.

- 16Steven Erlanger, “What Does It Mean to Provide ‘Security Guarantees’ to Ukraine?” New York Times, January 10, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/10/world/europe/ukraine-russia-security-guarantees.html.

- 17“Ukraine: Apparent War Crimes in Russia-Controlled Areas,” Human Rights Watch, April 3, 2022, https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/04/03/ukraine-apparent-war-crimes-russia-controlled-areas.

- 18“Congress Approved $113 Billion of Aid to Ukraine in 2022,” Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, January 5, 2023, https://www.crfb.org/blogs/congress-approved-113-billion-aid-ukraine-2022.

- 19Many advocates of extending security guarantees to Ukraine do not bother to justify their proposal in U.S. security terms beyond arguing that it will deter Russia and protect Ukraine. They assume that Ukrainian and U.S. interests are the same. On the differences between U.S. and Ukrainian interests sese Patrick Porter, Justin Logan, and Benjamin H. Friedman, “We’re Not All Ukrainians Now,” Politico Europe, May 17, 2022, https://www.politico.eu/article/ukraine-russia-war-nato-eu-us-alliance-solidarity/.

- 20Theodore Lowi, “Making Democracy Safe for the World: Foreign Policy and National Politics,” in Domestic Sources of Foreign Policy, ed. James N. Rosenau (New York: Free Press, 1967), 295–331.

- 21Justin Logan and Benjamin H. Friedman, “The Case for Getting Rid of the National Security Strategy,” War on the Rocks, November 4, 2022, https://warontherocks.com/2022/11/the-case-for-getting-rid-of-the-national-security-strategy/; Ben Friedman, “Biden is Exaggerating the Stakes of Ukraine,” UnHerd, June 3, 2022, https://unherd.com/thepost/joe-biden-is-exaggerating-the-security-stakes-of-ukraine/.

- 22Christopher McCallion, “Assessing Liberal and Realist Explanations for the Russo-Ukrainian War” Defense Priorities, June 7, 2023, http://defensepriorities.org/explainers/assessing-realist-and-liberal-explanations-for-the-russo-ukrainian-war.

- 23Samir Puri, Russia’s Road to War with Ukraine: Invasion Amidst the Ashes of Empires (London: Biteback Publishing, 2022), 79–106.

- 24William J. Burns, The Back Channel: A Memoir of American Diplomacy and the Case for Its Renewal (New York, Random House, 2019), 233.

- 25John J. Mearsheimer, “Why the Ukraine Crisis Is the West’s Fault: The Liberal Delusions That Provoked Putin” Foreign Affairs 93, no. 5 (September/October 2014): 77–89. Powerful states are reliably “neuralgic” about hostile alliances on their border. See Stephen Van Evera, “To Prevent War and Secure Ukraine, Make Ukraine Neutral,” Defense Priorities, February 19, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/to-prevent-war-and-secure-ukraine-make-ukraine-neutral.

- 26“Amb. Michael McFaul: U.S. Has ‘a Major Strategic Interest to Help the Ukrainians Win the Battle of Donbas’,” MSNBC, April 20, 2022, https://www.msnbc.com/andrea-mitchell-reports/watch/amb-michael-mcfaul-u-s-has-a-major-strategic-interest-to-help-the-ukrainians-win-the-battle-of-donbas-138149445774; Atlantic Council, “Why Ukraine’s Success is in the U.S. National Interest,” video, YouTube, February 4, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K6OUQe_Za18. See also “Russia’s War in Ukraine: How Does it End?” Council on Foreign Relations, May 31, 2022, https://www.cfr.org/event/russias-war-ukraine-how-does-it-end. See also Alina Polyakova and Daniel Fried, “Putin’s Long Game in Ukraine,” Foreign Affairs, February 23, 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/ukraine/2022-02-23/putins-long-game-ukraine.

- 27“GDP (Current US$) – Ukraine, Russian Federation, European Union,” World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=UA-RU-EU.

- 28

- 29Stephen Van Evera, “Hypotheses on Nationalism and War,” International Security 18, no. 4 (Spring 1994): 5–39.

- 30Those states naturally want a U.S. ensured buffer, but the Russian weakness on display should lower fears of Russian, not raise them. Benjamin H. Friedman and Justin Logan, “Europe Can Stand on Its Own. The Ukraine Invasion Proves It.” Week, March 20, 2022, https://theweek.com/russo-ukrainian-war/1011475/europe-can-stand-on-its-own-the-ukraine-invasion-proves-it; Stephen Wertheim, “Europe is Showing That It Could Lead Its Own Defense,” Washington Post, March 3, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2022/03/03/europe-defense-nato-ukraine-war/.

- 31Leonid Bershidsky, “War in Ukraine So Far Favors the Defense,” Japan Times, June 14, 2023, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2023/06/14/commentary/world-commentary/russia-ukraine-war-6/; Frank Hoffman, “American Defense Priorities after Ukraine,” War on the Rocks, January 2, 2023, https://warontherocks.com/2023/01/american-defense-priorities-after-ukraine/.

- 32Steven Erlanger, “If a Divided Germany Could Enter NATO, Why Not Ukraine?” New York Times, May 26, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/26/world/europe/ukraine-nato-germany.html.

- 33Marc Trachtenberg, A Constructed Peace: The Making of the European Settlement, 1945-1963 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999), 95–145.

- 34

Johan Hassel, Kate Donald, and Laura Kilbury, “Why the United States Must Stay the Course on Ukraine,” Center for American Progress, February 22, 2023, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/why-the-united-states-must-stay-the-course-on-ukraine/; Joseph R. Biden Jr., “President Biden: What America Will and Will Not Do in Ukraine,” New York Times, May 31, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/31/opinion/biden-ukraine-strategy.html; Quoted in Robin Wright, “Ukraine is Now America’s War, Too,” New Yorker, May 1, 2022, https://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/ukraine-is-now-americas-war-too. See also Marc A. Thiessen, “If Putin is Allowed to Invade Ukraine, America’s Credibility Would Lie in Tatters,” Washington Post, February 8, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2022/02/08/ukraine-russia-war-united-states-china/; Robert C. O’Brien, “How to Teach Beijing a Lesson in Ukraine,” Foreign Policy, September 1, 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/09/01/china-taiwan-ukraine-war-lessons/?tpcc=recirc_latest062921;

Antony J. Blinken, “Secretary Blinken’s Press Availability,” U.S. Department of State, March 4, 2022, https://www.state.gov/secretary-antony-j-blinken-at-a-press-availability-15/. - 35Mark W. Zacher, “The Territorial Integrity Norm: International Boundaries and the Use of Force,” International Organization 55, no. 2 (Spring 2001): 215–250.

- 36Samuel Charap and Miranda Priebe, “Avoiding a Long War: U.S. Policy and the Trajectory of the Russia-Ukraine Conflict,” Rand Corporation January 2023, https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PEA2510-1.html.

- 37On the decline of interstate war and reduced benefits of conquest see, John Mueller, “Retreat from Doomsday: The Obsolescence of Major War (New York: Basic Books, 1989); 321–328; Carl Kaysen, “Is War Obsolete? A Review Essay,” International Security 14, no. 4 (Spring 1990): 42–64; Stephen Van Evera, “Primed for Peace: Europe After the Cold War,” International Security 15, no. 3 (Winter 1990–91): 7–57.

- 38“Open Letter Calling for Limited No Fly Zone,” Politico, March 8, 2022, https://www.politico.com/f/?id=0000017f-6668-ddc5-a17f-f66d48630000.

- 39Thomas Schelling, Arms and Influence (New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press, 2008).

- 40On the continuation of plans to strike first in U.S. nuclear planning into the present see, Benjamin H. Friedman, Christopher A. Preble, and Matt Fay, “The End of Overkill? Reassessing U.S. Nuclear Weapons Policy, Cato Institute White Paper, September 24, 2013, https://www.cato.org/white-paper/end-overkill-reassessing-us-nuclear-weapons-policy.

- 41Daryl Press, Calculating Credibility: How Leaders Assess Military Threats (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2007), 8–28.

- 42Benjamin Tallis, “Security Guarantees for Ukraine,” German Council on Foreign Relations June 30, 2023, https://dgap.org/en/research/publications/security-guarantees-ukraine-0.

- 43Friedman, Preble, and Fay, The End of Overkill?

- 44“Memorandum on Security Assurances,” December 5, 1994, https://policymemos.hks.harvard.edu/files/policymemos/files/2-23-22_ukraine-the_budapest_memo.pdf?m=1645824948.

- 45On the idea that may U.S. security commitments during the Cold War were bluffs see Marc Trachtenberg, “Robert Jervis and the Nuclear Question,” University of California, Los Angeles, December 22, 2011, https://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/polisci/faculty/trachtenberg/cv/Jervis(34a).doc.

- 46This is sort of moral hazard, a concept from insurance where the beneficiary takes risks because the insurer bears the cost of the risk. On U.S. protection encouraging moral hazard, or “reckless driving” among allies and other potentially protected parties, see Barry R. Posen, Restraint: A New Foundation for U.S. Grand Strategy (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2014), 65–67; Alan J. Kuperman, “Mitigating the Moral Hazard of Humanitarian Intervention: Lessons from Economics,” Global Governance 14, no. 2 (Spring 2008): 219–224. Ukraine’s circumstance is somewhat different, because thinks it does not bear the risk when it actually does. It is like buying fake insurance. On this point see Benjamin H. Friedman, “Biden Doesn’t Like Russia’s Meddling in Ukraine. But He’s Not Prepared to Stop It.” NBC, May 6, 2021, https://www.nbcnews.com/think/opinion/biden-doesn-t-russia-s-meddling-ukraine-he-s-not-ncna1266535; Natalie Armbruster and Benjamin H. Friedman, “Who is an Ally, and Why Does it Matter?,” Defense Priorities, October 12, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/who-is-an-ally-and-why-does-it-matter.

- 47Robert Jervis, Perception and Misperception in International Politics: New Edition (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2017), 120–122.

- 48U.S. Department of State, “U.S.-Ukraine Charter on Strategic Partnership,” November 10, 2021, https://www.state.gov/u-s-ukraine-charter-on-strategic-partnership/.

- 49Michael Crowley, “Blinken Will Visit Ukraine in Show of Support Against Russia,” New York Times, April 30, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/30/us/politics/blinken-biden-ukraine-russia.html; Matthias Williams, “Ukraine’s Yermak Assured of “Ironclad” U.S. Support in Call With Sullivan—Tweet,” Reuters, November 26, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/ukraines-yermak-assured-ironclad-us-support-call-with-sullivan-tweet-2021-11-26/; Jim Garamone, “Defense Secretary Says U.S. Commitment to NATO Defense ‘Ironclad,’” U.S. Department of Defense, February 17, 2022, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/2938530/defense-secretary-says-us-commitment-to-nato-defense-ironclad/.

- 50W.J. Hennigan, “Obama Approves $75 Million in Nonlethal Aid to Ukraine,” Los Angeles Times, March 11, 2015, https://www.latimes.com/world/europe/la-fg-us-ukraine-aid-20150311-story.html.

- 51Mike Sweeney, “Saying ‘No’ to NATO: Options for Ukrainian Neutrality,” Defense Priorities, August 12, 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/saying-no-to-nato-options-for-ukrainian-neutrality; Van Evera, “To Prevent War and Secure Ukraine, Make Ukraine Neutral.”

- 52Stephen Bryen, “War Looms as U.S. and Kiev Ignore Minsk II Protocols,” Asia Times, February 21, 2022, https://asiatimes.com/2022/02/war-looms-as-us-and-kiev-ignore-minsk-ii-protocols.

- 53Kenneth Waltz, Theory of International Politics (Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, Inc., 2010).

- 54Puri, Russia’s Road to War with Ukraine.

- 55Burns, The Back Channel, 233; Thomas L. Friedman, “Now a Word from X,” New York Times, May 2, 1998, https://www.nytimes.com/1998/05/02/opinion/foreign-affairs-now-a-word-from-x.html.

- 56Puri, Russia’s Road to War with Ukraine, 255–256.

- 57McCallion, “Assessing Liberal and Realist Explanations for the Russo-Ukrainian War.”

- 58Van Evera, “To Prevent War and Secure Ukraine, Make Ukraine Neutral.”

- 59Andrew Cheatham, “Is ‘Neutralization’ Obsolete After the Ukraine War?” United States Institute of Peace, June 2, 2022, https://www.usip.org/publications/2022/06/neutralization-obsolete-after-ukraine-war.

- 60Guy Chazan and Henry Foy, “Western Allies Plan to Provide Long-Term Security Assurance to Ukraine,” Financial Times, June 14, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/8f0528ba-45a4-42c0-b099-07a34e2ee9ff.

- 61As noted, the Russia’s poor military performance in the war strengthens the case for European strategic autonomy and other terms for European states developing greater collective military capability without the United States. Mike Sweeney, “How Would Europe Defend Itself?,” Defense Priorities, April 11, 2023, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/how-would-europe-defend-itself.

More on Europe

Trump’s ‘Donroe Doctrine’ flaunts U.S. expansionism and intervention. But will it pay off long-term?

Featuring Jennifer Kavanagh

January 25, 2026

January 23, 2026

January 20, 2026

Events on Ukraine