December 15, 2025

An armed nonalignment model for Ukraine’s postwar security

Summary

Determining arrangements for Ukraine’s postwar security will be a critically important element of a negotiated end to the Russia-Ukraine war. A lasting peace will require an agreement that addresses both Kyiv’s fears about future Russian aggression and Moscow’s security concerns, including those focused specifically on Ukraine and those related to Europe’s security architecture more broadly.

The prewar status quo will not be acceptable to either combatant. In talks that have occurred since 2022, Moscow has consistently demanded that, in any war settlement, Kyiv accept territorial concessions and commit to permanent neutrality that would end Ukraine’s bid for membership in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), limit its security ties with the alliance, and eliminate the prospect of NATO forces being based inside Ukraine.1Charap and Radchenko, “The Talks That Could Have Ended the War in Ukraine.” Moscow has also indicated that an acceptable deal would impose restrictions on Ukraine’s military capabilities to forestall the emergence of Ukrainian armed forces that are able to threaten Russian territory or Russian-occupied territory in Ukraine with long-range missiles and other capabilities. Ukraine has suggested that it will not accept a settlement that leaves it both without security guarantees or military partnerships and demilitarized so that it is unable to defend itself. To last, any agreement to end the war will need to leave Ukraine confident that it can, at the very least, deter aggression and defend itself if attacked.

In this report, I explore a possible model for Ukraine’s postwar security arrangements that might satisfy these competing security concerns and demands—a version of armed nonalignment that excludes membership in military alliances, such as NATO, but would provide Ukraine the military capabilities it needs to deter future attacks and defend itself if deterrence fails, without direct Western military intervention. Such a Ukrainian military force would serve as Kyiv’s primary assurance against future war, but it would lack capabilities to pose a real threat to Russia, thus addressing Moscow’s most serious concerns. For peace to take hold and endure, both sides will need to feel that a settlement sufficiently addresses their security concerns; Ukraine’s armed nonalignment offers a way to do so.

The purpose of this report is to examine how armed nonalignment could work in Ukraine, first by comparing it with potential alternative arrangements for Ukraine’s postwar security and then looking at the mechanics of such a model, including how Ukraine could establish its nonalignment and what would be required to defend the country sufficiently. With Western assistance focused on artillery ammunition, artillery rockets, and air defense, along with investments in Ukraine’s own defense production, Kyiv would need about five years after the settlement of the war to establish a strong and credible defensive posture that is sufficient to protect the territory under its control and hold off any future aggression.

Scope

In this report, I focus on one possible model for Ukraine’s postwar security arrangements, which will be one of several key elements of a negotiated end to the war. Any negotiated settlement will have to address a range of other issues, including territorial control, sanctions, humanitarian issues, and commitments from Russia to address insecurity created by its invasion of Ukraine. All of these issues will be as essential to a final settlement as Ukraine’s postwar security arrangements, but are beyond the scope of this report.

Security arrangements for Ukraine

Conversations about Ukraine’s future security tend to revolve around three dimensions: security guarantees, military alignment, and the size and capabilities of Ukraine’s military force.

Security guarantees and commitments are arrangements in which one country or group of countries promises another country military protection or assistance to support its national defense during peacetime or in the event of external aggression. The term security guarantee is sometimes used broadly to cover a variety of different types of support, but its literal definition is much narrower. In the context of U.S. military and diplomatic parlance and documents, a security guarantee is a binding commitment to support another country’s self-defense in the event of an attack, implicitly suggesting direct involvement of U.S. military forces in that contingency. NATO’s Article 5 and similar provisions in U.S. security agreements with Japan and South Korea are security guarantees under this definition, but other commitments (for example, providing military aid) are not.

Ukraine has long sought security guarantees that would ensure direct Western military intervention if it were attacked again in the future, such as the commitment in Article 5. Such aspirations are understandable but not realistic and could prove a challenge for negotiating a lasting settlement. The United States proved unwilling to offer such a commitment to Ukraine in the past, and the same is true of most of Europe. Russia has suggested that it will continue fighting rather than accept such an outcome as part of a settlement. Security commitments that fall short of Article 5 are more likely. These could include promises of peacetime military support to build Ukraine’s defensive capabilities or additional U.S. or European military aid, intelligence-sharing, and sanctions and economic pressure should Russia invade Ukraine in the future.

A country’s military alignment primarily consists of its membership in military alliances. Countries that choose to be neutral commit to avoiding alliances and other security partnerships that would force them to take sides should hostilities commence. For Ukraine, formal alignment with the United States or Europe would most likely occur through NATO membership or some other bilateral or multilateral military alliance. Such an outcome may be out of reach for Ukraine, given limited willingness of the United States and most key states in Europe to enter a formal alliance with Ukraine. Furthermore, Russia has long rejected the possibility of U.S. or European military forces in Ukraine.

Under neutrality, Ukraine would give up the possibility of NATO membership and eschew participation in other mutual defense treaties and organizations while agreeing to bar foreign forces from Ukrainian territory and limit military cooperation with foreign partners that might force Ukraine to take sides in a future conflict. Nonalignment does not have a formal legal definition and so is a flexible concept. Nonaligned states do not join formal military alliances, but they often have a range of different types of security partnerships that fall below that level. In practice, nonaligned states also aim to maintain a degree of military independence, which can mean limiting the basing of foreign forces or avoiding arrangements that include deep military integration with a partner.

The final area for consideration is the size and capabilities of Ukraine’s military. Ukraine’s military has grown in size, skill, and capabilities since Russia’s full-scale invasion began in February 2022. On the one hand, Russia has demanded Ukraine’s demilitarization as a condition for a settlement, calling for the country’s military to be capped in size and capabilities. On the other hand, Ukraine would like a large military force that is capable of maintaining a forward defense posture and is armed with extensive offensive and defensive capabilities, including long-range strike. There are, of course, a variety of options between these two stances, some of which involve voluntary limits on Ukraine’s military force and others that impose mutual restrictions on both Ukraine and Russia (for example, geographic commitments regarding the basing of forces or capabilities). As with Ukraine’s alignment, these options will ultimately be negotiated between the war’s stakeholders.

Ukraine’s postwar security arrangements will likely be the outcome of the negotiations that end the war. As argued in this report, arrangements that include military alignment with the United States or security guarantees that promise intervention by U.S. and other NATO military forces lack credibility; Western countries have refused to make these commitments in the past. These arrangements also face political challenges in the United States, Russia, and Ukraine. Therefore, the most likely outcome seems to be one in which Ukraine would be either neutral or nonaligned, with the exact parameters to be decided on during negotiations, and armed through a mix of indigenous production and Western security assistance that gives Ukraine capabilities to secure its territory.

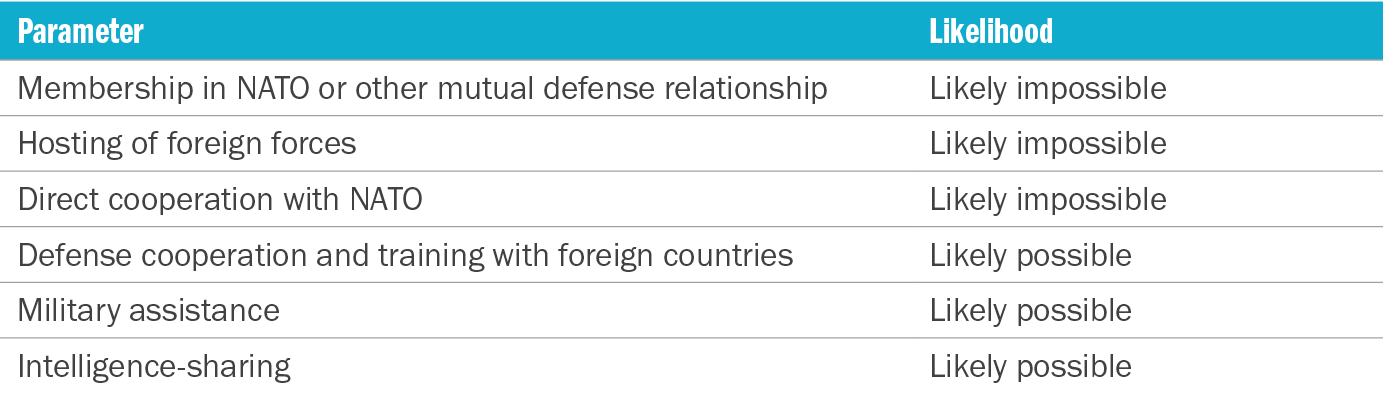

Parameters of Ukraine’s nonalignment

Ukraine’s postwar security arrangement is likely to be bespoke, designed to bridge its security concerns, as well as those of Russia, as best possible. Although the terms of Ukraine’s nonalignment will be subject to negotiation, it is possible to sketch out a set of conditions that might satisfy (at least minimally) both sides and key third parties.

Some of the likely parameters are obvious. For example, under any interpretation of nonalignment, Ukraine will have to agree to forgo NATO membership and membership in other mutual defense organizations and military alliances, including with the United States and European countries. Russia could also insist that Ukraine further agree to limit direct forms of military cooperation with NATO. Moscow will probably push for restrictions on foreign forces located inside Ukraine, including on a permanent or rotational basis.

Nonalignment should not preclude all defense cooperation between Ukraine and European states or the United States, however, nor would it leave Ukraine unprepared for its own defense. Training activities conducted outside Ukraine, including in Europe and the United States, on a bilateral or multilateral basis (outside of NATO), would likely continue. Ukraine’s nonalignment need not exclude all military assistance either. For example, defense-oriented military aid from the United States and other NATO allies and economic investment in Ukraine’s defense industrial base should proceed. Ukraine’s nonalignment would also not preclude European Union (EU) membership. Ukraine might adopt a protocol limiting its involvement in some of the EU’s defense and security mechanisms, as other neutral EU states have done.

In peacetime, under nonalignment, intelligence-sharing arrangements between Ukraine and Western partners would differ from the wartime status quo. Intelligence and warning intended to allow Ukraine to protect its civilians and critical infrastructure from external aggression or internal terrorism should continue. However, the targeting data and the satellite imagery mapping Russian military movements and activities that Ukraine has relied on during the war to launch offensives and conduct strikes would not be necessary and could be curtailed during peacetime. These mechanisms could be renewed if Russia seemed ready to invade Ukraine again.

Beyond defining the terms of a peace deal, Ukraine, its Western partners, and Russia will need to find a credible and enduring way to establish Ukraine’s nonalignment that is also feasible given Ukraine’s domestic political constraints. Russia will likely demand formal and binding commitments from Ukraine and its Western partners to implement and guarantee Ukraine’s nonalignment. Verbal promises or informal commitments will likely not be credible or sufficient for Russia because Ukraine’s NATO aspirations are codified in its constitution and affirmed in NATO policy.

Ukraine’s nonalignment—at least as it pertains to NATO—could be established by the United States and its NATO allies agreeing to formally close NATO’s open door, committing not to add any new alliance members beyond the current 32 members, or at least close membership to Ukraine. NATO members are unlikely to agree to such a step, given that they have long refused to allow outside powers—namely Russia—to have a veto over alliance membership. Similar resistance would likely impede efforts to revise NATO’s 2024 commitment on Ukraine’s “irreversible” path to joining the alliance or revoke the 2008 promise that Ukraine would become a NATO member.2NATO, “Statement of the NATO-Ukraine Council.”

An alternative would be for Ukraine to formally adopt nonalignment, either for an indefinite period or permanently. This could be accomplished in two main ways—constitutional change or United Nations (UN) Security Council resolution. First, Ukraine could amend its constitution to formally adopt nonaligned status and rule out NATO membership or military alliances of any kind. Ukraine has maintained a version of nonalignment in the past, but the experience of the war with Russia since 2022 would likely make a constitutional change prohibitively difficult.

A different and, perhaps more feasible, approach would be for Ukraine’s nonalignment to be established in a binding UN Security Council resolution, as was outlined in the draft of the Istanbul Communiqué negotiated in 2022. A UN Security Council (UNSC) resolution supported by its members and possibly affirmed by other states (such as the those in NATO) would give Ukraine’s neutral status an international imprimatur and some longevity because any change would have to be approved by all UNSC members, including Russia. It would also give the rest of NATO a way to affirm their own commitment to honoring Ukraine’s nonaligned status.

One challenge to this approach is that a UNSC resolution on Ukraine’s nonalignment would conflict with the country’s constitution. This might not be a deal-breaker, especially if used as an interim solution. The language in Ukraine’s constitution on the country’s commitment to pursue NATO membership is broad and does not include a timeline or specific commitments by the president. If nonalignment leads to a durable peace and an end to Russian aggression, a change to Ukraine’s constitution may be more possible.

Arming a nonaligned Ukraine

A nonaligned Ukraine would be responsible for its own defense. Ukraine’s best strategy would be a defensive one focused on territorial denial, sometimes called a porcupine defense. The approach would aim to deter Russia by giving Kyiv the defensive capabilities needed to make any future attempt by Russia to take additional slices of Ukraine’s territory prohibitively costly. In case of deterrence failure, Ukraine would have the capabilities to deny an aggressor its objectives through attrition.

This rule of thumb, used widely in campaign analyses such as this one, suggests that for every one defender, the aggressor needs three soldiers to mount a successful offensive (a 3:1 offense-to-defense ratio).3O’Hanlon, The Future of Land Warfare; Posen, “Europe Can Defend Itself”; Davis, Aggregation, Disaggregation, and the 3:1 Rule in Ground Combat; Zumbrun, “How a Simple Ratio Came to Influence Military Strategy.” Applying this to the Ukraine case would suggest that if Russia attacks with around 500,000 troops along the country’s 1,000-km eastern front line—the typical size of the Russian force on Ukraine’s eastern front over the course of the war—Ukraine would need about 170,000 troops on defense. A more conservative ratio of 2:1 would put that requirement at 250,000. This would allow for about 250 personnel per kilometer, which would match recommendations from U.S. military doctrine which continue to be used by U.S. military planners.4Department of the Army, Commander and Staff Organization and Operations. Ukraine can likely get by with a smaller total number of frontline forces if needed because of the role of drones and passive defenses in the war, which have replaced personnel to some extent.

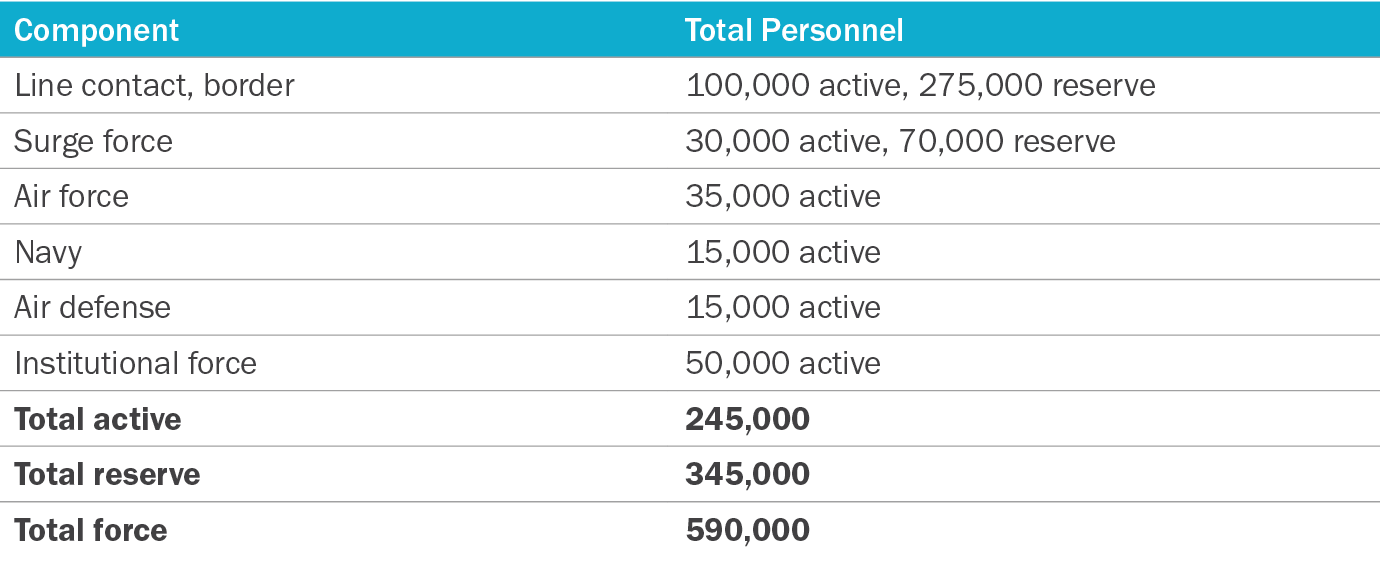

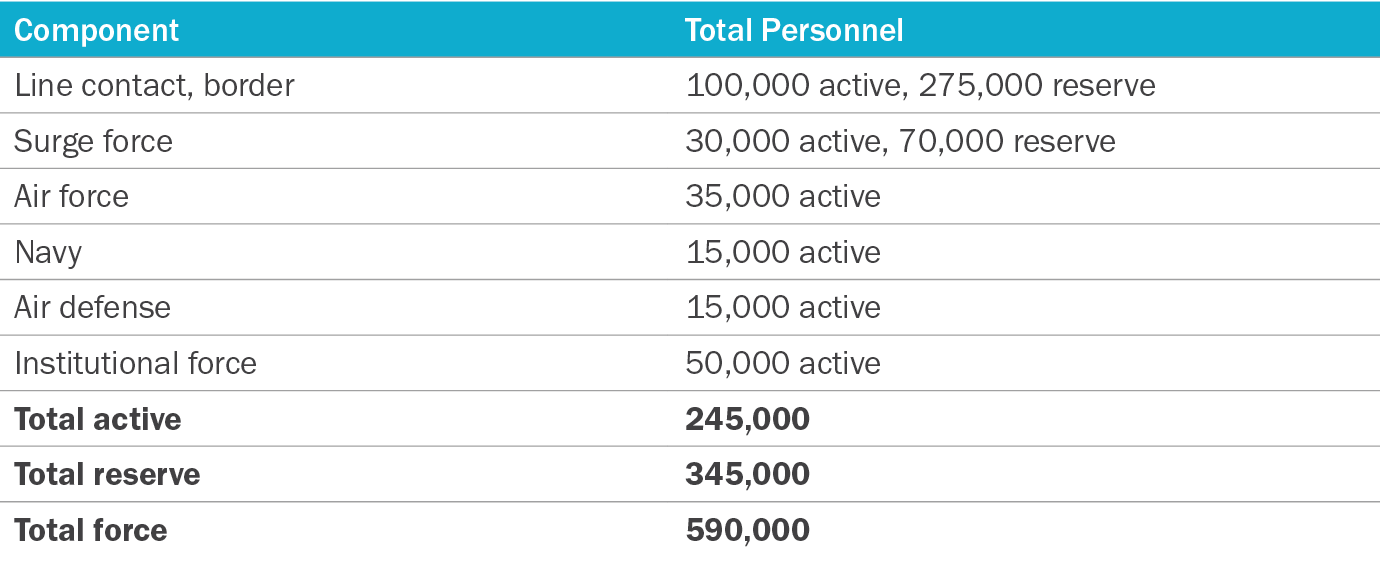

Along the rest of Ukraine’s line of contact (an additional 1,000 km), Kyiv can likely rely on half this number of forces, given the more-limited fighting in this zone. The border with Belarus can likely be protected during peacetime with border guards—Russia has not attacked through this region since the very beginning of the war, and the terrain is inhospitable to invaders—and with surge forces during wartime. Ukraine will also need about 100,000 personnel to man this surge force and, based on its anticipated holdings of air defense systems, about 15,000 personnel dedicated to air and missile defense. Its current 50,000 personnel devoted to air and naval operations are likely sufficient. Finally, it will need an institutional component to deal with training, acquisition, recruiting, and other similar tasks. These personnel would be divided into active-duty forces and a high-readiness reserve that could be called up in 24 to 48 hours, as shown in Table S.1.

Table S.1: Total forces required for Ukraine’s self-defense

A military of this size would not pose a threat to Russia, which has been able to maintain over 500,000 personnel in Ukraine since the early months of the war. Moscow should, therefore, be willing to accept a Ukrainian military with these general dimensions. Given demographic and resource constraints, a military of this size would be on the upper edge of what Ukraine can sustain and afford, so it should not be necessary to negotiate caps as part of the settlement, which would be politically difficult in Kyiv.

Turning to military capabilities, a defensive denial strategy would rely on a narrow set of military weapons and systems, including anti-tank and anti-personnel mines, cheap attritable drones, short-range artillery and ammunition of many kinds, and the construction equipment, cement, and other materials needed to build barricades, fortifications, and trenches. Ukraine should not need more tanks, however, as they have served limited purpose in the current war. Along its coasts, Ukraine would need naval mines, antiship missiles, and surface and subsurface sea drones. To protect its skies, Ukraine would rely on air defense of many types and ranges, as well as counterdrone and electronic jamming supplemented by aircraft, including the F-16s that it has already received and its remaining Soviet-era fleet.

Ukraine would benefit from a small stockpile of precision missiles—mostly short-range (less than 80 km) rockets and some extended range systems. Long-range missiles with a reach of 500 km or more can support Ukraine’s defense of its civilian infrastructure and strategic targets by giving Kyiv the capability to strike and destroy (also known as the ability to hold at risk) a larger number of Russia’s drone and missile launch platforms. However, the benefits of a long-range strike capability should not be overestimated. Russia will always have the ability to reposition its launch platforms farther away and continue attacks. It also has a larger number of missiles and launchers that give significant resilience to Ukrainian deep strikes. Relying on long-range missiles is also costly and inefficient as a means of defense and deterrence, given Ukraine’s limited resources. Ukraine may derive some deterrent value and some tactical gains from a small stockpile of indigenously produced long-range missiles, but these missiles need not be a centerpiece of Ukraine’s porcupine strategy.

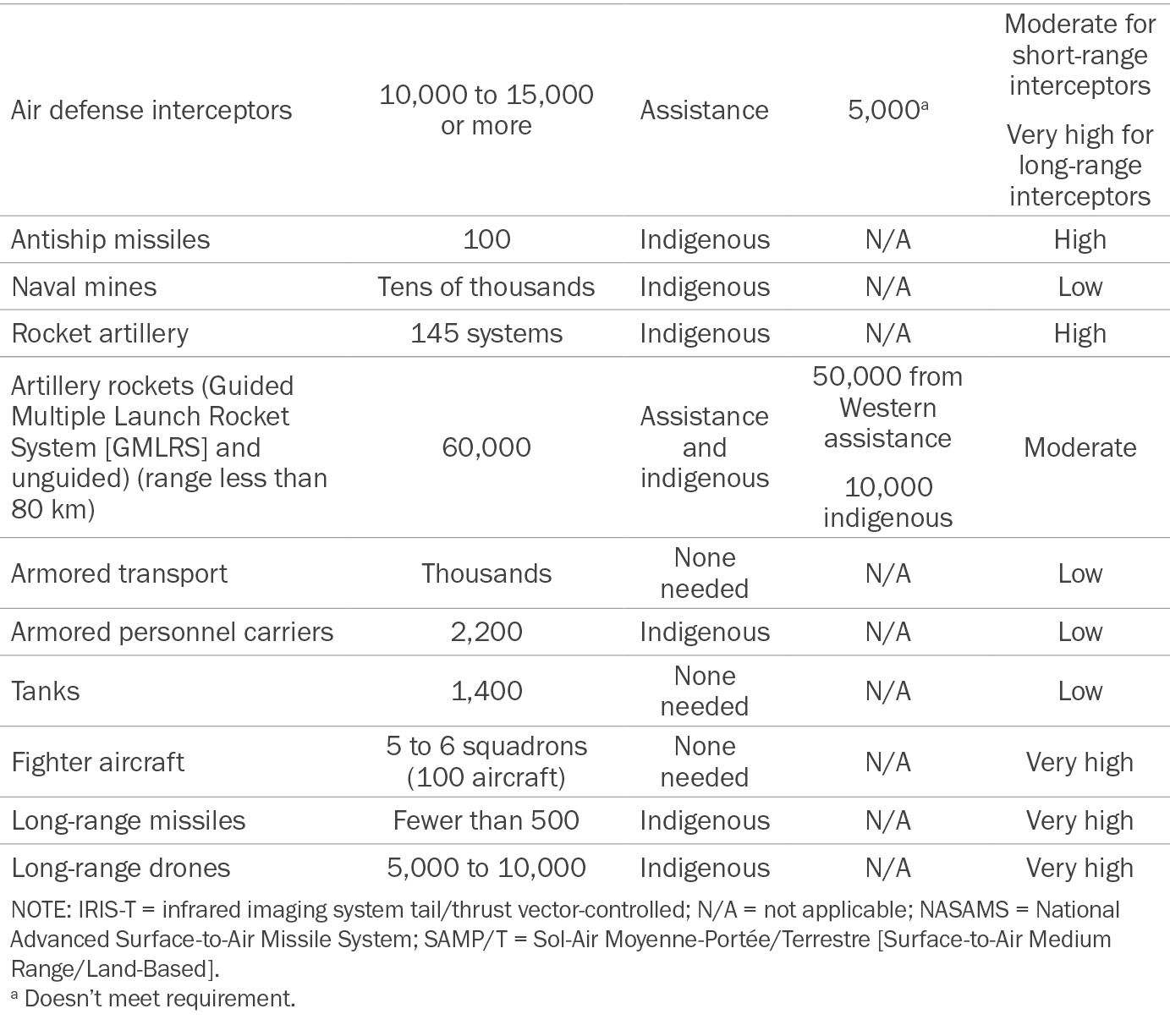

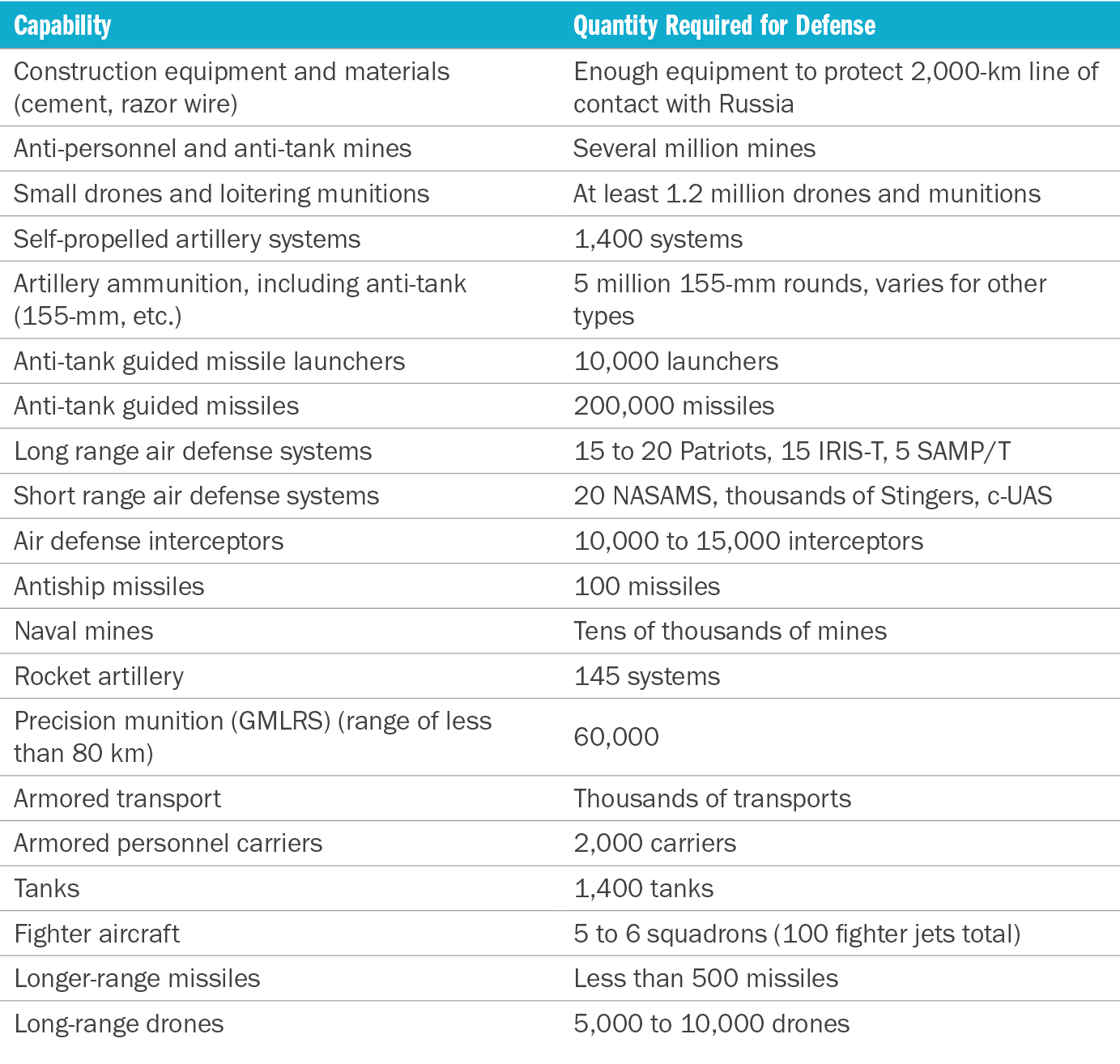

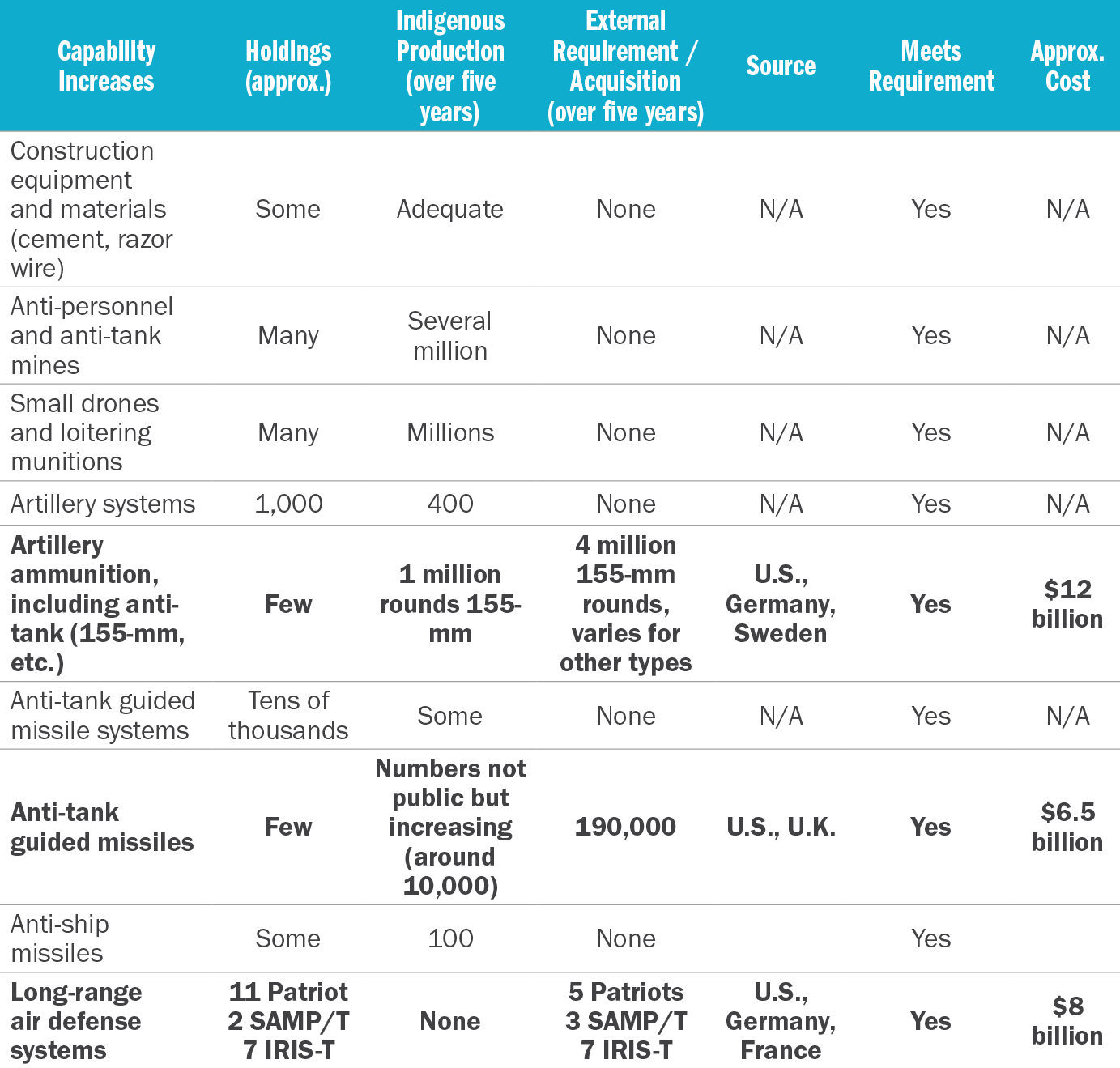

Experience from the Russia-Ukraine war since 2022 can offer guidelines for determining what and how much Ukraine will need to stockpile. It seems reasonable that Ukraine would want to stockpile about a year’s worth of munitions and drones. Doing so would give Kyiv and its partners (if needed and available) time to ramp up production of key systems to supply Ukraine’s military for a longer war. Other metrics may offer better benchmarks for other capabilities. For artillery systems, infantry fighting vehicles, and tanks, for example, it makes more sense to figure out how many of these would be needed to equip a force of the size required for a defensive denial strategy (Table S.2). For air defense, the relevant metric is the number of missiles and drones fired by Russia at Ukrainian cities over the course of the war. Some systems, such as long-range strike, are not strictly required for a defensive strategy. Ukraine’s requirements are listed in Table S.2.

Although many have expressed doubts that Ukraine can build a military capable of deterring Russia over the long term, Ukraine can indeed meet the requirements for a robust defensive military capability in a period of about five years. It can meet these targets largely by relying on indigenous production and Western assistance for only munitions, air defense systems, and interceptor missiles. The hardest area to meet Ukraine’s likely requirements is air defense; Kyiv will need to rely on a mix of systems and likely continue to invest in interceptor missiles beyond the five-year timeline considered here. The required Western assistance is also summarized in Table S.2 and comes with a price tag of $41.5 billion over five years.

Table S.2: Capabilities required for Ukraine’s self-defense

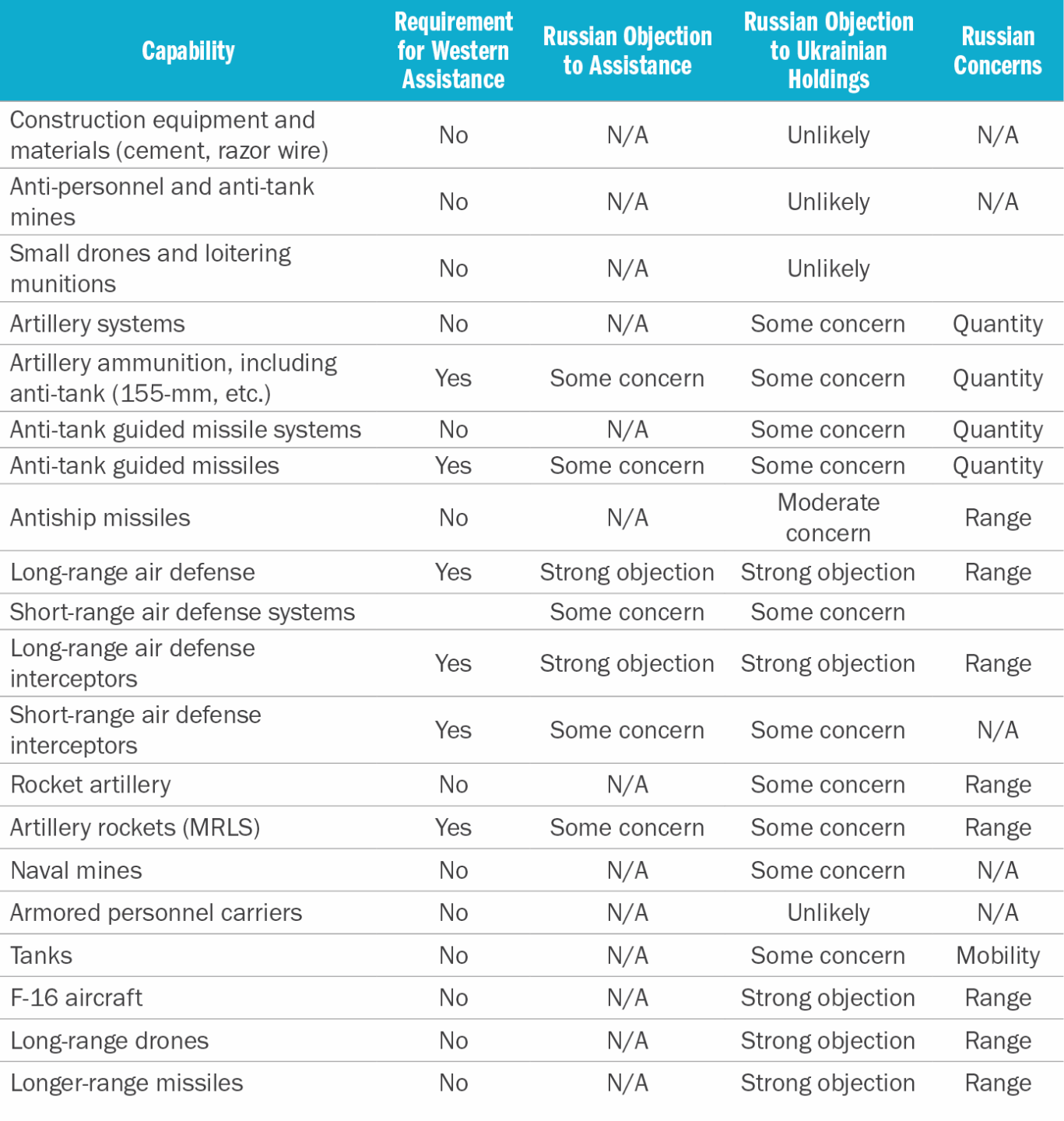

For the most part, the armed Ukraine envisioned in this analysis should not elicit Russian concerns. Of the Western assistance recommended by this analysis, the only sensitive area would be long-range air defense and interceptor missiles, especially longer-range PAC-2 missiles, which Ukraine has used for offensive strikes. Such systems as combat and early warning aircraft and long-range missiles would likely be concerns for Russia if they were included in Western assistance.

Russia’s possible objections to Ukraine’s military holdings will likely be similar. Long-range missiles, long-range air defense, and combat and early warning aircraft will be of primary concern because of their ability to collect data on and strike targets deep inside Russian territory. U.S. High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems (HIMARS) could trigger Russian objections because they can fire much longer-range missiles than the ATACMS that Ukraine has a small stockpile of, including the Precision Strike Missile (PrSM). Russian sensitivities about Ukraine’s indigenous rocket artillery and most types of ammunition are also likely to be on the low side, with the possible exception of Ukraine’s antiship missiles because of the threat that they could pose to Russia’s Black Sea fleet.

Russia has expressed more concerns about Ukraine’s indigenous production of long-range missiles, of which it now has several variants with ranges longer than 500 km and up to 3,000 km. Ukraine should be allowed to continue this domestic production. Rates of production of these missiles are too low to contribute to large stockpiles, but Ukraine’s ability to produce these missiles in large numbers could grow. This is one of several areas in which negotiators might be able to orchestrate trades, extracting Russian concessions for compromises from Ukraine on areas of concern for Moscow. One approach for long-range missiles might be to allow Ukraine to stockpile some number of cruise and ballistic missiles domestically, maybe in the low hundreds, and then store anything beyond this outside the country, in strategic stockpiles that would be released if Ukraine were attacked again.

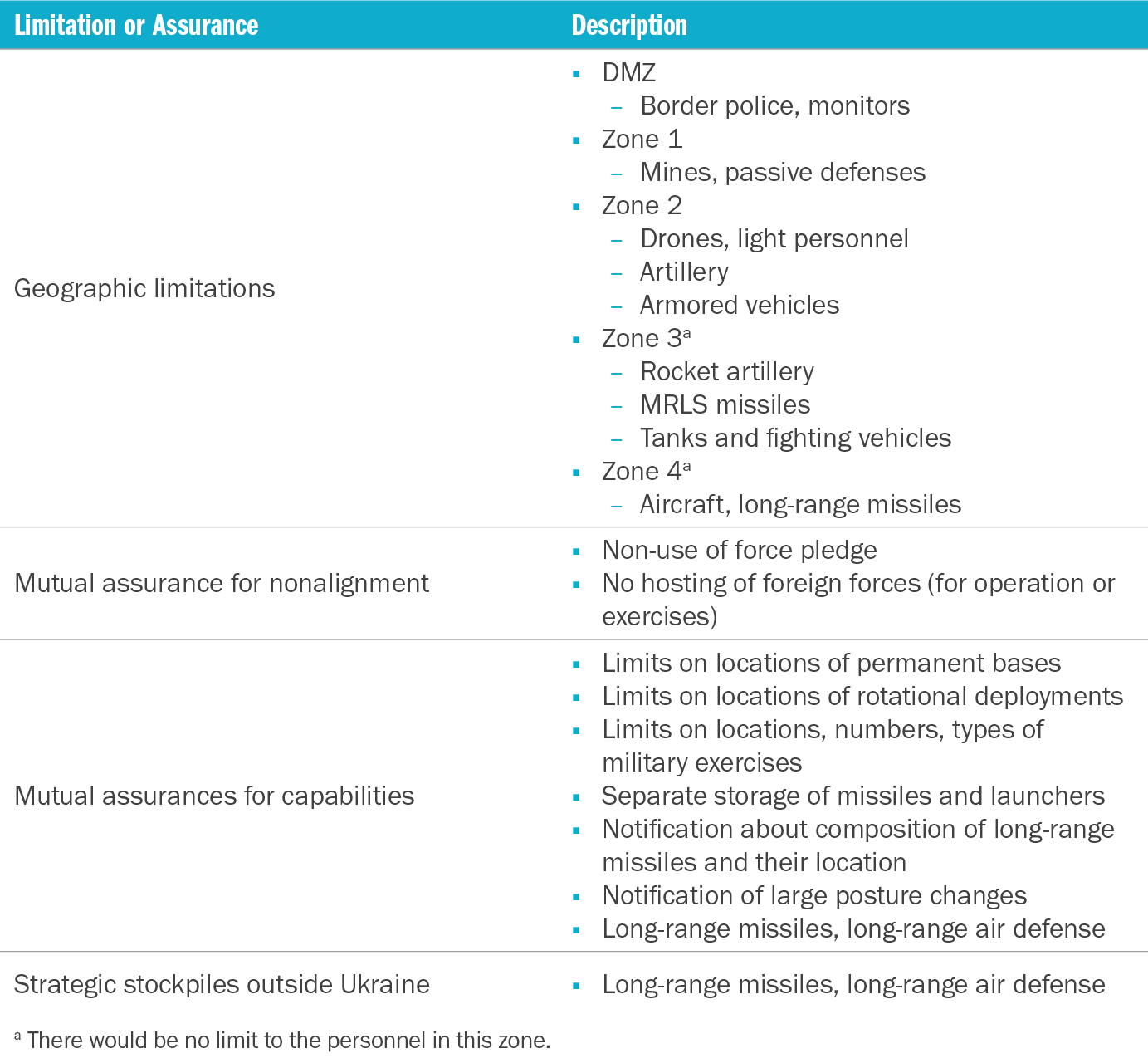

Geographic limitations and mutual assurances

Ensuring that any settlement endures will require arrangements to further reduce both sides’ threat perceptions. This might be accomplished by instituting a set of self-imposed geographic restrictions on the deployment of certain military capabilities and forces equipped with certain types of weapons. Such geographic limitations would be adopted on a mutual basis: Russia and Ukraine would agree to reciprocal conditions even if they are not symmetrical in nature. For Ukraine, such measures would reduce the threat of a surprise attack. Given the reduced threat that Ukraine would pose as a nonaligned, defensively postured state, Russia should be willing to take steps to reassure Kyiv that it would not take action if Ukraine does not continue to push for NATO membership. Indeed, such Russian concessions would be another advantage of armed nonalignment for Ukraine.

As a starting point, a settlement should establish a demilitarized zone (DMZ), in which all military personnel and equipment would be prohibited. Ideally this DMZ would be quite wide, up to 10 or 15 km, and stretch across both sides of the line of contact between the two parties. The DMZ would not be the same width across the 2,000-km border, nor would it be symmetrical on the two sides, as it would need to account for the geography, demography, and other features that will vary on the Ukrainian and Russian sides.

Beyond the DMZ, a settlement between Russia and Ukraine could benefit from a series of additional geographic restrictions aimed at creating a larger buffer between the two sides. Verification and monitoring will be difficult and require buy-in from both combatants, as well as an enforcement mechanism. In the current context, one approach might be to establish four security zones on each side of any DMZ. In the first, passive defenses, drones, and light ground personnel (perhaps up to 50,000 troops) would be allowed to operate. At a distance of around 50 km would be a second zone, with short-range artillery, anti-tank guns, and armored vehicles with some heavy forces. The third zone would include Multiple Launch Rocket Systems (MLRS) and rocket artillery at a distance of 100 km, as well as tanks and fighting vehicles. The final zone would apply to long-range missiles and aircraft and might start at a distance of 200 km from the line of contact. As a secondary safeguard, missiles and launchers could be stored separately.

Finally, there is the question of air defense. Limits on short-range air defense and interceptors should not be needed, but some accommodation might be required for longer-range air defense and interceptors. At the very least, more-advanced air defense systems, such Patriots and their Russian equivalents, could be placed at least 50 km from the line of contact with exceptions negotiated for major cities. Other assurances might include transparency between the two sides when it comes to the locations of long-range air defense radars or arrangements that store interceptor missiles and air defense systems separately.

Key findings

The following key findings arise from this research:

- Armed nonalignment is the most feasible approach to Ukraine’s postwar security because it can ensure Ukraine’s ability to defend itself and deter aggression while addressing Russia’s security concerns and accounting for political and resource constraints in the United States and Europe.

- Comparisons to other countries’ security models are instructive, but Ukraine’s nonaligned status will be bespoke. Ukraine will need to formalize this status in some way to make the commitment credible.

- Russia will likely insist on no North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) membership and no hosting of foreign forces. However, Ukraine would continue military exercises with Western partners outside of Ukraine and defense industrial integration with those partners, outside of a formal alliance structure.

- Ukraine will need about 245,000 active-duty forces and a reserve force of at least 345,000 to meet its security and deterrence needs. This will be close to the maximum force size that Ukraine can feasibly recruit and fiscally sustain.

- Using a combination of indigenous production and Western assistance, Ukraine can build a robust military deterrent, including a year’s supply of all types of ammunition and a six-months supply of air defense interceptors, in about five years after the end of the war.

- Ukraine can rely on its own defense production to meets its postwar needs for drones, artillery systems, and armored vehicles. It should not require more tanks and aircraft and can rely on limited domestic production for long-range missiles.

- Ukraine will need Western-provided short-range munitions, air defense systems, and interceptors. This aid could be structured as formal security assurances to Ukraine.

Next steps for implementation

Although it would not be Kyiv’s ideal outcome, armed nonalignment offers Ukraine the surest path to a secure future. It is Ukraine’s most credible security arrangement because it leaves the country’s future defenses in the hands of its own military. It is also the most likely scenario to support an enduring settlement that avoids a return to war, and it is the most feasible outcome, given the constraints on each relevant stakeholder.

Still, implementing Ukraine’s armed nonalignment will come with challenges. There are sure to be disagreements between Ukraine and Russia over some of the details of commitments on each side and what the postwar Ukrainian military will look like. Whatever the final terms, the commitments and requirements of every party (i.e., Russia and Ukraine, but also the United States and European states) should be clearly and transparently defined. Working-level dialogues in the United States, Ukraine, and Russia can begin to sketch out these conditions even as fighting continues in anticipation of an end in the medium term.

Chapter 1: Introduction

Determining arrangements for Ukraine’s postwar security will be a critically important element of a negotiated end to the Russia-Ukraine war. A lasting peace will require an agreement that addresses both Kyiv’s fears about future Russian aggression and Moscow’s security concerns, including those focused specifically on Ukraine and those related to Europe’s security architecture more broadly. The prewar status quo will not be acceptable to either combatant.

In the talks that have occurred since 2022, Moscow has consistently demanded that, in any war settlement, Ukraine commit to permanent neutrality that would prevent Ukraine’s membership in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), limit its security ties with the alliance, and rule out the presence of foreign forces inside Ukraine.5Charap and Radchenko, “The Talks That Could Have Ended the War in Ukraine.” Moscow has also insisted on limits to Ukraine’s military capabilities, presumably to minimize threats to Russian territory or Russian-occupied territory in Ukraine.6Faulconbridge, “Putin, Ascendant in Ukraine, Eyes Contours of a Trump Peace Deal”; Soldatkin and Antonov, “Putin Says Any Ukraine Peace Deal Must Ensure Russia’s Security, Vows No Retreat.” Because, at the time of this writing, Russia has the advantage on the battlefield and can afford to keep fighting, Moscow has considerable leverage to push for terms that meet these requirements.

Ukraine will not agree to a war settlement that leaves it both without external security guarantees and demilitarized so that it is unable to defend itself.7Government of Ukraine, “What Is Zelenskyy’s 10-Point Peace Plan?” Kyiv could probably be forced into an unfavorable settlement if conditions on the battlefield worsen or the United States cuts off military aid, but an imposed surrender of this kind is unlikely to last. Instead, an insecure Ukraine that fears renewed Russian aggression would have the incentive (and probably the will and capabilities) to undermine a ceasefire on these terms, either by resuming hostilities outright or by using irregular warfare to impose costs on Russia. To last, a war settlement will need to leave Ukraine confident that it can, at the very least, deter future aggression and defend itself if attacked.

Given these daunting requirements, the most feasible option for Ukraine’s postwar security—and likely the only one able to minimally satisfy requirements for both sides—is a version of armed nonalignment.8For more on the concept of nonalignment, see Rothstein, “Alignment, Nonalignment, and Small Powers: 1945–1965”; Vital, The Survival of Small States; Radoman, Military Neutrality and Nonalignment as Security Strategies of Small States; Ørvik, The Decline of Neutrality 1914–1941; and Flanagan and Osler Hampson, Securing Europe’s Future; and Ørvik, Semi-Aligned Security. Under armed nonalignment, Ukraine would be outside the NATO and other collective defense organizations, but it would not be left defenseless. Instead, it would be armed with defensive military weapons—provided through agreements with the United States and European states—sufficient to deter a renewed Russian invasion and to defend the territory under its control in case deterrence fails. To reduce both sides’ concerns about the risk of new attacks, negotiations could dictate geographic constraints on the deployment of long-range missiles and drones, tanks, and other offensive capabilities. Such provisions should not be unilateral. Instead, if Ukraine agrees to self-limitations on the geographic locations of certain military capabilities or military forces and exercises, Russia should adopt a similar set of self-imposed restrictions.

Ukraine’s armed nonalignment would thus have benefits for both combatants and give them assurances to address their mutual distrust.9Kavanagh, Safeguarding U.S. Interests in a Ukraine War Settlement; Kavanagh and McCallion, “Armed Neutrality for Ukraine Is NATO’s Least Poor Option.” Relying on its own military forces for security will ensure that Ukraine is not left relying on foreign promises that could turn out to be hollow. It is also a means by which Ukraine can get Russia to accept some constraints on its own military capabilities, effectively providing another layer of security for Ukraine. At the same time, armed nonalignment goes the furthest of any settlement options toward addressing Russia’s security concerns with respect to Ukraine’s NATO membership, Western alignment, and military capabilities.

Despite these benefits, however, armed nonalignment has its critics. There are those who argue that armed nonalignment will not work to make or keep peace. These skeptics expect that such an arrangement would leave Ukraine with military capabilities too weak to defend its territory and do little more than set the stage for another Russian invasion.10Ash et al., How To End Russia’s War on Ukraine. If armed nonalignment were to come with onerous caps on Ukraine’s offensive and defensive military capabilities, this might be true. But such caps are not a required component of the armed nonalignment model. Even a final arrangement that limited certain offensive capabilities would still leave the country with the capabilities to protect the territory under its control as long as sufficient defensive weapons and systems were permitted.11Kavanagh and McCallion, “Armed Neutrality for Ukraine Is NATO’s Least Poor Option.” Ukrainian decisionmakers, including President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, increasingly acknowledge that Ukraine’s own military force will act as the central guarantee of the country’s security. After a March 2025 meeting of Europe’s leaders, Zelenskyy said, “[i]t’s obvious that the strength and size of the Ukrainian army will always be a key guarantee of our security.”12As quoted in Irish and Pineau, “Europeans Back Strong Ukraine Army, Differ on Future ‘Reassurance Force.’” This is the essence of armed nonalignment.

Voices on the Russian side criticize armed nonalignment for the opposite reason. Although they welcome that the approach would prevent Ukraine from entering NATO or other military alliances with the West, these critics are concerned that armed nonalignment will allow for a Ukrainian army that is large and well equipped enough to launch successful offensive operations against Russian territory or Russian-occupied territory in Ukraine.13Dickinson, “Putin’s Dream of Demilitarizing Ukraine Has Turned into His Worst Nightmare”; Posen, “Putin’s Preventive War.” This group of critics warns that Moscow will continue to fight (or resume fighting) rather than accept the risk of one of these undesirable outcomes.14Mefford, “The Finlandization Fallacy.”

No postwar arrangement will leave either Ukraine or Russia feeling totally secure.15I thank Eric Ciaramella for his comments on this point. Ukraine will always fear that Russia will resume its aggression. Russia will have to accept that Ukraine is likely to be better prepared militarily than it was before the war and a determined enemy to Russia for decades to come. Still, armed nonalignment is the most plausible model for Ukraine’s postwar security and the one that meets both sides’ minimum requirements for national security. It can also provide a stable equilibrium of capabilities and mutual deterrence after the war that will be conducive to a lasting settlement.

Agreeing on the details of such an arrangement will be difficult. Several sets of issues will need to be addressed. For example, Ukraine will need a way to establish its nonaligned status that is credible to Russia but also feasible, given its legal and constitutional requirements. Even trickier, there will need to be at least a tacit mutual understanding on what a future armed Ukraine might look like, including the size and capabilities of Ukraine’s military.

Beyond agreement between Ukraine and Russia, a plan for Ukraine’s armed nonalignment will need to determine which types of Western military assistance will be used to arm Ukraine and where this assistance will come from. These are not insignificant questions, given constraints on available defense production in the United States and Europe. In fact, the success of armed nonalignment will depend heavily on the ability of the United States, Europe, and Ukraine to build up Ukraine’s defensive military capabilities so that the country can preserve its remaining territory and deter future Russian aggression. Doing so will take time, but Ukraine’s military need not be built in a month or even a year. Russia will need time to rest its soldiers and refit its military forces, affording Kyiv and its Western partners five to ten years after a settlement to strengthen Ukraine’s defenses.16Grisé et al., Russia’s Military After Ukraine. Timing will be important; Ukraine will want to build the core of its defensive barriers quickly and work to fill in other capabilities over time, but U.S. and European defense production constraints may limit the speed of any buildup.

Scope

Ukraine’s postwar security arrangements will be one of several key elements of a negotiated end to the war. This negotiated outcome will also address a variety of other issues, including control of territory, phased relief of sanctions, humanitarian issues, and, importantly, commitments from Russia to address the insecurity its aggression has created in Ukraine and Europe. These issues will be essential to a lasting settlement and are no less important than the specific arrangements required for Ukraine’s postwar security, but they are beyond the scope of this report.

Methodology and structure

In this report, I consider the feasibility of implementing armed nonalignment as Ukraine’s postwar security model. I will first consider the full variety of security arrangements that might be available to Ukraine and their advantages and disadvantages, including the extent to which these arrangements can support a lasting settlement and which are most politically feasible, given considerations of credibility and the concerns of key stakeholders. I will then examine the different ways that armed nonalignment could be implemented, including legal mechanisms to establish Ukraine’s nonaligned status, what an armed Ukraine might look like, and how Ukraine would get access to necessary weapons to support its self-defense in the short or long term. To do so, I combine a variety of methodologies, including a historical review of similar cases, extensive analysis of Ukrainian military campaign analysis to evaluate requirements, and an assessment of the defense production capacities of Ukraine, European states, and the United States. These methodologies are supplemented with findings from unstructured discussions conducted with Russian and Ukrainian military experts over the course of 2025.

The key takeaway is that it appears possible to build an armed and nonaligned Ukraine capable of defending itself within about five years after the war, given some limited U.S. and European support, while still addressing Russia’s security concerns. Should this approach be adopted as part of a future settlement, this report can offer a roadmap for policymakers to move toward implementation.

Chapter 2: Alternative security arrangements for Ukraine

The following are likely to be the three dimensions of Ukraine’s postwar security model:

- Security guarantees and commitments are arrangements in which one country or a group of countries promises another country military protection or assistance to support its national defense during peacetime or in the event of external aggression.17Walter, “The Critical Barrier to Civil War Settlement”; Fortna, Peace Time. The term security guarantee is sometimes used broadly to cover a wide variety of different types of support, but in the context of U.S. military and diplomatic parlance and documents, a security guarantee typically refers only to binding commitments to support another country’s self-defense in the event of an attack, including by sending U.S. military forces. NATO’s Article 5 and similar provisions in U.S. security agreements with Japan and South Korea are security guarantees under this definition. Other commitments—for example, the promise of military aid—are not.18Bilefsky, “Ukraine Has Asked for ‘Security Guarantees’ to Make Peace with Russia. What Does That Mean?”; Charap and Shapiro, “Elements of an Eventual Russia-Ukraine Armistice and the Prospect for Regional Stability in Europe.” Israel does not have a formal security guarantee from the United States, for instance, but does have a codified security commitment that includes military aid and promises from Washington to take remedial action if Israel is attacked (by Egypt).19Charap and Shapiro, “Elements of an Eventual Russia-Ukraine Armistice and the Prospect for Regional Stability in Europe.” For Ukraine, postwar arrangements could vary and include binding guarantees of direct military support in the event of a future attack or more-limited commitments of peacetime or wartime military aid. It is also possible, however, that Ukraine would be without security guarantees and commitments of any kind.

- Military alignment is determined primarily by a country’s alliances and formal security partnerships, especially those that determine which side it might take in a conflict.20Charap and Shapiro, “Elements of an Eventual Russia-Ukraine Armistice and the Prospect for Regional Stability in Europe”; Soldatenko, “Exploring Ukraine’s Armed Neutrality or Nonalignment”; Ørvik, Semi-Aligned Security; Mueller, “Alignment Balancing and Stability in Eastern Europe.” For Ukraine, formal alignment with the United States or Europe would occur most likely through NATO membership or some other bi- or multilateral military alliance. Under neutrality, Ukraine would give up seeking NATO membership and eschew participation in other mutual defense treaties and organizations; it would also agree to bar foreign forces from Ukrainian territory and limit military cooperation with foreign partners that might force Ukraine to take sides in a future conflict.21Soldatenko, “Exploring Ukraine’s Armed Neutrality or Nonalignment.” Nonalignment does not have a formal legal definition and is a more flexible concept. Nonaligned states do not join formal military alliances but often have a variety of different types of security partnerships that fall below that level. In practice, nonaligned states also aim to maintain military independence, which can mean limiting the basing of foreign forces or arrangements that include deep military integration with a partner. Ukraine’s postwar security arrangement will be bespoke and could include some mix of these formal and informal categories.

- The size and capabilities of Ukraine’s military have grown since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.22Kuzan, “Ukraine’s Growing Military Strength Is an Underrated Factor in Peace Talks”; Sanders, “Ukraine’s Third Wave of Military Reform 2016–2022.” On the one hand, Russia has demanded Ukraine’s “demilitarization” as a condition for a settlement, hoping to see the country’s military capped in size and capabilities.23Graham, “Russia’s Peace Demands on Ukraine Have Not Budged.” On the other hand, Ukraine would like a large military force that can maintain a forward defense posture armed with extensive offensive and defensive capabilities, including long-range strike.24Irish and Pineau, “Europeans Back Strong Ukraine Army, Differ on Future ‘Reassurance Force.’” There are, of course, a variety of options in between, some involving voluntary limits on Ukraine’s military force and others using mutual restrictions on Ukraine and Russia (e.g., geographic commitments regarding the basing of forces or capabilities). As with Ukraine’s alignment, this will ultimately be negotiated between the war’s stakeholders.

Choices made across these three dimensions could result in a variety of different security models for Ukraine, some of which have historical precedents or present-day manifestations, which will be discussed in this chapter. Ukraine’s final security arrangement will not look exactly like any of those examples; it will be unique based on Ukraine’s specific circumstances, how the war ends, and what happens at the negotiating table. But these cases, their advantages and disadvantages, and the conditions under which they endured or collapsed can help map out the option space for Ukraine. Likewise, an examination of the feasibility of these historical models, focused on credibility and political concerns, can identify which security parameters may be most within reach for Ukraine.

Exploring alternative security arrangements

Table 2.1 shows a variety of models that vary based on the security guarantees and commitments, military alignment, and military capabilities. Ukraine’s ultimate postwar security arrangement will not be an exact replica of any one of the cases presented here but may be some mix of parameters taken from these examples and designed specifically for Ukraine.

Table 2.1: Security models

Alliances and quasi-alliances

NATO and other U.S. mutual defense relationships

The most desirable approach from Ukraine’s perspective would be one that combines credible security guarantees with clear Western alignment and no caps on its military forces. The best multilateral example of this security arrangement is NATO. Members of NATO receive binding security guarantees under Article 5, which states that an attack on one member state will be viewed as an attack on all member states. NATO member states also have their own militaries of varying sizes and capabilities.25NATO, Handbook, 2006. Some NATO members have modified arrangements to fit their specific needs or to address sensitivities and geographic considerations. Norway is a member of NATO but does not permit the permanent deployment of allied forces on its territory or host U.S. nuclear weapons. Denmark has a similar set of limitations on foreign deployments during peacetime, including a stipulation that foreign forces cannot deploy on Danish territory unless invited.26Ørvik, Semi-Alignment and Western Security. These countries are still integrated into NATO institutions, however, and are covered by the Article 5 guarantee.27Westfall and Ilyushina, “Here’s What Russia and Ukraine Have Demanded to End the War.”

At the bilateral level, the United States has similar mutual defense relationships with such countries as Japan and South Korea. These countries enjoy U.S. security guarantees that promise American military support in the event of external aggression, including, if necessary, direct participation by U.S. military forces. As a part of both the NATO alliance and these bilateral mutual defense commitments, the United States has historically based large numbers of U.S. military personnel in Europe, Japan, and South Korea.28Japan-U.S. Security Treaty; Mutual Defense Treaty Between the United States and the Republic of Korea.

Feasibility for Ukraine

These models are likely not feasible for Ukraine. The most significant reason for this lack of feasibility has to do with credibility. The United States and other NATO allies have twice in the recent past (2014 and 2022) refused to send military forces to directly support Ukraine following Russian invasion and continue to refuse to send military personnel to Ukraine. Having already revealed their lack of political will to fight for Ukraine, and in the absence of some major political or strategic shift, offering Ukraine an alliance commitment or NATO membership that would entail a binding promise to do what has already been refused would seem hollow.29Goldberg, “The Obama Doctrine”; Wolf, “Here’s What Biden Has Said About Sending US Troops to Ukraine.” Notably, the NATO-lite options adopted by Norway and Denmark would suffer from these same basic limitations.

Critics of this line of reasoning could argue that it is Ukraine’s lack of alliance membership that explains why NATO members stayed on the sidelines in 2014 and 2022.30Centre for Eastern Studies “If Ukraine Was in NATO, Would Russia Have Attacked?” It is impossible to evaluate this counterfactual with any certainty, but the history of U.S. military operations makes clear that the United States does not need a formal treaty commitment to send military forces to intervene in conflicts in which Washington sees U.S. interests at stake.31Kavanagh et al., Characteristics of Successful U.S. Military Interventions. The decisions made by U.S. Presidents Barack Obama, Joseph Biden, and Donald Trump not to intervene offer strong evidence that U.S. policymakers do not see vital U.S. interests on the line in Ukraine.32Kavanagh and McCallion, “Armed Neutrality for Ukraine Is NATO’s Least Poor Option.”

Accepting Ukraine as a NATO member would create new political pressures for U.S. military action if Ukraine were attacked again and raise the stakes for U.S. credibility, but these pressures and stakes are still no guarantee that the United States or other NATO members would respond by sending military forces into Ukraine.33Kavanagh and McCallion, “Armed Neutrality for Ukraine Is NATO’s Least Poor Option”; Friedman, “Neutrality not NATO: Assessing security options for Ukraine”; Logan and Shifrinson, “Don’t Let Ukraine Join NATO.” Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty specifies that, in the event of an attack on a member state, other members “will assist the Party or Parties so attacked by taking forthwith, individually and in concert with the other Parties, such action as it deems necessary.”34NATO, “Collective Defence and Article 5.” Military action is one possible response, but it is by no means promised or required.35Rumer, “Neutrality.” But there is no assurance that the politics would work in Ukraine’s favor, and much would depend on the United States’ decision, because the rest of Europe has shown limited ability or appetite for military action in Ukraine without U.S. backing.36Fornusek, “‘Coalition of the Willing’ for Ukraine Stalls over Lack of US Backstop, Bloomberg Reports.”

There are other reasons why Ukraine is unlikely to receive NATO membership or a bilateral alliance with the United States. First, especially under the Trump administration, Washington has made clear that Ukraine will not receive NATO membership as an outcome of this war, in part because there is a growing reluctance in Washington to take on additional security responsibilities in Europe and especially in Ukraine. This position is not unique to Trump, however. Presidents Biden and Obama also assessed that Ukraine’s strategic importance to the United States did not warrant NATO membership or direct U.S. military intervention against Russia’s invasions.37Bose and Singh, “Trump: Not Practical for Ukraine to Join NATO, Get Back All Land.”

Even if the United States was willing to offer Kyiv this type of deal, Russia is almost certain to reject a settlement that leaves Ukraine allied with the United States inside or outside NATO. Moscow has made its insistence on Ukraine’s nonalignment a core demand; Russia will likely prefer continued war over such an outcome.38Menkiszak and Rodkiewicz, “Meeting in Istanbul.” Ukraine’s NATO membership is thus not a realistic condition for an armistice.

Israel model

Beyond the formal alliance model, the United States has several quasi-allies with which it does not have treaty commitments but does have unique military relationships and semi-alignment. As one example, the United States first extended a limited security commitment to Israel in the 1973 treaty that ended the war with Egypt. As a part of this settlement, the United States promised to take “remedial action” if Egypt were to violate the ceasefire, though what this entailed was never specified.39Charap and Shapiro, “Elements of an Eventual Russia-Ukraine Armistice and the Prospect for Regional Stability in Europe”; Ciarmella, Envisioning a Long-Term Security Arrangement for Ukraine; Lewis, “The United States and Israel.” The relationship was further formalized in a 1975 memorandum of agreement between Israel and the United States that committed Washington “to be fully responsive, within the limits of its resources and Congressional authorization and appropriation, on an on-going and long-term basis to Israel’s military equipment and other defense requirements, to its energy requirements and to its economic needs.”40Memorandum of Agreement Between the Governments of Israel and the United States. The United States committed to providing Israel military aid each year, including money that could be invested in Israel’s defense industrial base. Since 1981, this aid has been guided by the concept of the qualitative military edge that the United States aims to provide Israel in terms of its military technology compared with its regional neighbors. The concept has no formal definition but often includes access to the most-advanced U.S. systems and intelligence before other countries in the region.41Haig, statement for the record submitted in response to question from Clarence Long.

Israel enjoys wide latitude when it comes to the types of military assistance it can receive from the United States—very little is off-limits—and it has built a large and capable military. The original memorandum of agreement has been extended in ten-year increments since 1975; Israel now receives close to $4 billion in military assistance per year.42“Rubio Signs Declaration to Expedite Delivery of $4 Billion in Military Aid to Israel”; U.S. Department of State, “U.S. Cooperation with Israel”; Masters and Merrow, “U.S. Aid to Israel in Four Charts.” Israel also benefits from other types of U.S. military support that fall just short of a full security guarantee. The United States frequently surges military power into the Middle East whenever Israel seems to face a heightened threat from abroad and has even acted as a backstop of sorts, offering air defense support when Israel has faced kinetic attacks. In 2024 and 2025, for instance, the United States supported Israel’s efforts to shoot down Iranian drones and missiles aimed at Israeli targets and eventually joined Israel’s war against Iran, conducting airstrikes on Iranian nuclear targets.43Clayton and Zanotti, “Israel-Iran Conflict, U.S. Strikes, and Ceasefire.”

Feasibility for Ukraine

Many have suggested that the Israel model would be a good one for Ukraine—including Kyiv itself. However, this model is most likely not replicable, at least not as a package. As with the alliance models described above, there are credibility considerations. The United States provides Israel a level of support that it is has not been willing to provide Ukraine in terms of types of direct military aid and security assistance (e.g., weapons). Although the United States assisted Israel in shooting down missiles launched toward its territory by Iran, Washington has explicitly refused to do the same for Ukraine.44Melkozerova, Gramer, and McLeary, “Ukraine Bridles at No-Holds-Barred US Support for Israel.” The United States also sells Israel advanced missiles, aircraft, and other defense systems that it has not been willing to send to Ukraine. An offer to Ukraine of an Israel-style commitment in the future, when the United States has demonstrated a willingness to do so thus far, would not be credible.

There are also political limitations and constraints that Ukraine would face that Israel does not. Military support to Israel is bolstered by historically bipartisan U.S. political support that Ukraine does not enjoy. In fact, there is political resistance to long-term commitments of military aid to Ukraine, especially from some in the U.S. Republican Party.45Riccardi, “How Stalled U.S. Aid for Ukraine Exemplifies GOP’s Softening Stance on Russia.” This resistance would be a possible barrier to any potential application of the Israel model to Ukraine.

Although the Israel model is unlikely to work for Ukraine in full, some aspects of this model could be useful (for example, the remedial action commitment made by the United States in 1973). In Ukraine’s case, the United States or other NATO allies might promise to provide additional military assistance, expand intelligence-sharing, or impose new economic costs on Russia if Moscow were to invade Ukraine again.

Taiwan model

Taiwan also has a special security relationship with the United States.46Ciarmella, Envisioning a Long-Term Security Arrangement for Ukraine. The United States had a mutual defense agreement with Taiwan up until 1979, when the United States shifted its diplomatic recognition to China. In response to this move, the U.S. Congress then passed the Taiwan Relations Act. This act commits the United States to continue to augment Taiwan’s defenses with defensive military assistance and “to maintain the capacity of the United States to resist any resort to force or other forms of coercion that would jeopardize the security, or the social or economic system, of the people on Taiwan.”47Public Law 96-8, Taiwan Relations Act. The legislation does not specify which types of aid or measures would be required, which gives the U.S. President some discretion. Taiwan is therefore not formally a U.S. ally, nor does it have a U.S. security guarantee. But, in practice, its relationship with the United States is deeper than the average security partner, in a sort of semi-alignment.

U.S. policy toward Taiwan has long been one of strategic ambiguity, in which Washington neither commits to defend Taiwan nor definitively declines to do so, in hopes of simultaneously deterring China from using coercion against the island and Taiwan from declaring independence.48Glaser, Bush, and Green, Toward a Stronger U.S. Taiwan Relationship. The United States continues to send weapons to Taiwan and reportedly has military trainers on the island, despite Beijing’s protestations.49Ciaramella, Envisioning a Long-Term Security Arrangement for Ukraine; Green and Glaser, “What Is the One China Policy and Why Does It Matter?” The U.S.-China bargain over Taiwan has worked so far, preventing a war in the Taiwan Strait. But the equilibrium is under threat, and Taiwan remains the flashpoint that is most likely to drag the United States and China into a war.

Feasibility for Ukraine

As with the Israel model, some parts of the Taiwan model are replicable for Ukraine, but others are very clearly not. The United States could make a formal, codified commitment to supply Ukraine arms to support its defense, as it did for Taiwan.50Public Law 96-8, Taiwan Relations Act; Gordon, “A Security Guarantee for Ukraine?” In fact, something similar already exists, signed under President Biden as an executive agreement.51Bilateral Security Agreement Between the United States of America and Ukraine, June 13, 2024. The U.S.-Ukraine bilateral security agreement was signed in 2024 as a ten-year arrangement that committed the United States to “build and maintain Ukraine’s credible defense and deterrence capability.”52Soldatenko, “The U.S.-Ukraine Security Agreement Is What the Parties Will Make of It.” As with the Israel model, it is not clear that there is the same political appetite for an indefinite and open-ended commitment to Ukraine as there is for Taiwan, but some form and duration of U.S. military assistance after a settlement seems within reach.

It would be much harder, however, for the United States to credibly promise to “maintain the capacity of the United States to resist any resort to force or other forms of coercion that would jeopardize the security, or social or economic system, of the people” of Ukraine, when it has very clearly not done so in the past.53Public Law 96-8, Taiwan Relations Act. Moreover, the United States has long defined Taiwan as a crucial linchpin of American power. Ukraine has never held this level of importance for the United States, and it is unrealistic to assume that it would do so in the future.54Sentner, “Trump Gives His ‘Assurance’ for No US Boots on the Ground in Ukraine.” It is unlikely, then, that the United States would ever make such an expansive commitment to Ukraine as it did to Taiwan in 1979.

Neutral states

The models considered so far include only aligned states or states with de facto U.S. military alignments. There are also models for fully neutral and nonaligned states. As noted previously, neutral states stay outside military alliances and commit to avoid partnerships and commitments that would make it hard to avoid taking sides in a future conflict. Neutral states can have their own militaries and security guarantees, so long as those guarantees are not mutual defense commitments of any kind. There are several examples of this type of arrangement.

Belgium, Malta, and the Istanbul communiqué

Belgium from 1839 to 1914 is an example of a state that combined neutrality with binding multilateral security guarantees. By the terms of the Treaty of London of 1839, Belgium was made an independent state but accepted neutrality. This neutrality was guaranteed by the United Kingdom, Austria, Russia, France, and Prussia.55Treaty of London of 1839. Belgium had its own military force under this model, though it was small. This arrangement endured successfully for 75 years but collapsed in 1914 when German forces invaded Belgium on the way to France. In accordance with its obligations, the United Kingdom entered the war.56Treaty of London of 1839; Charap, “Ukraine’s Best Chance for Peace.” That the United Kingdom felt compelled to enter the war is evidence that its guarantees were quite credible.

A more recent but similar example is the case of Malta. After British forces left Malta in 1979, the country declared its neutrality and positioned itself with the Cold War nonaligned movement. Given Malta’s strategic location, however, NATO member states were concerned that they would lose their foothold on the island and the Soviet Union would seize the opportunity to expand its footprint. In 1980, Italy agreed to offer a security guarantee of Malta’s neutrality in case it faced external aggression.57Galea, “Malta and Neutrality”; U.S. Department of State, “U.S. Policy Toward Malta.” In 1981, Malta signed a parallel agreement with the Soviet Union under which Moscow agreed to support the island’s neutrality as well.58Galea, “Malta and Neutrality”; U.S. Department of State, “U.S. Policy Toward Malta.” Technically, as a successor to the Soviet Union, Russia has a commitment to recognize Malta’s neutrality. Malta is not without its own military, though it is small. It is also a member of the European Union (EU). If the Malta model were applied to Ukraine, a neutral Ukraine could receive a guarantee of its neutrality from the United States and sign an agreement with Russia to support this neutral status.59Soldatenko, “Exploring Ukraine’s Armed Neutrality or Nonalignment.”

A third variant of this model was included in the Istanbul communiqué, a draft proposal developed by Russia and Ukraine early in the war that set out the terms of a possible deal between the two countries. Although negotiations collapsed and the agreement was never signed, the framework is still referenced as a possible starting point for resumed settlement talks. Under the terms proposed in the communiqué, Ukraine would accept permanent neutrality, and, if the country were attacked again, the guarantors would be treaty bound to hold urgent and immediate consultations (which shall be held within no more than three days) among them, in the exercise of the right to individual or collective self-defense… will provide (in response to and on the basis of an official request from Ukraine) assistance to Ukraine, as a permanently neutral state under attack, by immediately taking such individual or joint action as may be necessary… using armed force in order to restore and subsequently maintain the security of Ukraine as a permanently neutral state.60As quoted in Soldatenko, “Exploring Ukraine’s Armed Neutrality or Nonalignment.”

The wording of the proposed guarantees was even more far-reaching than Article 5 in the demands it placed on guarantors. Russia later attempted to include a stipulation that would require any intervention to be agreed to by all guarantor states, giving Russia a veto over any military assistance offered to Ukraine. Ukraine objected to this provision, but it is unclear whether some agreement might have been reached if negotiations had endured.61Troianovski, Entous and Schwirtz, “Ukraine-Russia Peace Is as Elusive as Ever”; Soldatenko, “Exploring Ukraine’s Armed Neutrality or Nonalignment.”

Feasibility for Ukraine

Although the arrangement proposed in the Istanbul communiqué might have been acceptable to both Russia and Ukraine in 2022, implementing this model, the one used by Belgium in 1939, or the one used in Malta in 1981 would face challenges, in terms of both credibility and political will. Most importantly, any model that requires the United States or European countries to commit to send military forces to defend Ukraine (or, more precisely, its neutrality) in case of external aggression would not be credible because these countries have refused to do so in the past. The United States specifically could not credibly commit to offer Ukraine a guarantee like the one that Italy has provided Malta, because it has already proven that it is not willing to directly intervene to defend Ukraine. The Trump administration in particular has rejected any commitment that would include the possibility of U.S. forces on the ground participating in Ukraine’s defense.62Hegseth, “Opening Remarks by Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth at Ukraine Defense Contact Group (As Delivered).”

Beyond credibility, there are other political considerations that would interfere with the adoption of a model similar to that proposed in the Istanbul communiqué or used for Belgium in 1939. Russia has indicated that it is still open to an arrangement like the one outlined in Istanbul. However, for Ukraine, after four years of war, having Russia as one of its security guarantors is a nonstarter.63“Russia’s Lavrov Outlines Terms for Ukraine Peace: Big Power Security Guarantee.” Russia, meanwhile, has indicated that it will not accept an arrangement that includes security guarantees in which Moscow is not included as one of the guarantors. Combined with credibility concerns, political constraints seem to rule out the Istanbul or Belgium approach for Ukraine.

Finland during the Cold War

Neutrality does not always come with security guarantees, however. Finland’s situation during the Cold War is a case of a country that was forced to accept neutrality, had no security guarantees, and had caps placed on its military forces as a condition of the Treaty of Peace with the Soviet Union that was signed in 1947.64Treaty of Peace with Finland; Aunesluoma and Rainio-Niemi, “Neutrality as Identity?” In subsequent agreements with Moscow, Helsinki also accepted constraints on its foreign and defense policy and agreed to orient its military force away from its eastern border with Russia.65Agreement of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance between the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and the Republic of Finland.

Known as Finlandization, Finland’s Cold War model for foreign policy is generally described in negative terms and as an undesirable outcome for Ukraine or any other state, largely because of Finland’s forfeited control over its own military and defense decisions and the caps placed on its military development. But critics of Finlandization tend to ignore the successes of Finland’s Cold War approach to self-defense. Although its active-duty force was capped in size, no limits were placed on its reserve force, which Finland grew to consist of several hundred thousand high-readiness forces that could be mobilized and deployed quickly.66Arter, “From Finlandisation and Post-Finlandisation to the End of Finlandisation?”; Häkkinen and Kaarkoski, “Willingness to Defend and Foreign Policy in Sweden and Finland from the Early Cold War Period to the 2010s.” In addition, Finland’s total defense concept ensured that, beyond the active duty and reserve force, the country’s population was both resilient and ready to serve in civil defense roles as necessary.67Visuri, “Evolution of the Finnish Military Doctrine, 1945–1985.” Defense functions were localized, to an extent, and arms depots and command structures were decentralized to encourage rapid response and flexibility.68Visuri, “Evolution of the Finnish Military Doctrine, 1945–1985.”

Finland faced restrictions on military capabilities, including on air-to-air missiles (which it did not have until 1980) and modernized fighter aircraft (which it received in 1962). It was not until the late 1950s that Finland was even able to update its artillery systems. (Each of these changes was negotiated with the Soviet Union.69Visuri, “Evolution of the Finnish Military Doctrine, 1945–1985.”) To ensure its self-defense despite these constraints, Finland adopted a territorial defense strategy and invested heavily in its production of defensive military equipment not limited under the Paris Treaty, turning itself into a hard-to-attack porcupine.70Vital, The Survival of Small States; Tomas Ries, Cold Will. This territorial defense strategy relied on a variety of more-defensive capabilities—artillery and anti-tank mines, for instance—and exploited passive defenses, including physical barriers, hardening of infrastructure, and border surveillance, to respond quickly to border violations. The strategy also exploited Finland’s geography to support its self-defense, making use of its forests, rivers, and vast territory to create obstacles that would impede, entrap, and wear out any attackers.71Ålander, “Defense Capability—the Secret of Finnish Happiness?”; Wither, “Back to the Future?”; Ries, Cold Will. In terms of procurement, Finland focused on mobility and firepower to maximize the combat capability of its lean fighting force.72Visuri, “Evolution of the Finnish Military Doctrine, 1945–1985.”

It’s true that Finland’s post–World War II defense strategy was never tested by Moscow, but military analysts generally offer favorable assessments of Finland’s defensive strengths. Most importantly, the approach allowed Finland to preserve its sovereignty and maintain a stable relationship with its much bigger and better-armed neighbor.73Ries, Cold Will; Vital, The Survival of Small States. Moscow was satisfied with the arrangement. It did not control Finland, but it still benefited from a stable border on its northwestern flank.74Ålander, “Defense Capability—the Secret of Finnish Happiness?”; Ries, Cold Will; Vital, The Survival of Small States.

Feasibility for Ukraine

The Finlandization model is not one Ukraine will find ideal, but it is not necessarily a bad one, and it is more feasible and realistic than many of the other models discussed in this chapter.75Sweeney, “Saying ‘no’ to NATO—options for Ukrainian neutrality”; Van Evera, “To prevent war and secure Ukraine, make Ukraine neutral”; Friedman, “Neutrality not NATO: Assessing security options for Ukraine”; Kavanagh, “Safeguarding U.S. interests in a Ukraine war settlement.” Neutrality, or some form of nonalignment, would keep Ukraine out of NATO, addressing a core Russian redline. Meanwhile, Ukraine could replicate the defense strategy and procurement approach used by Finland to build strong defenses that are capable of deterring future aggression. On this score, Ukraine already has some advantages: Its military balance is more favorable compared with Russia than was true with Finland and the Soviet Union, and its defense industrial base is much stronger than Finland’s was.

There are some differences between Finland’s World War II experience and Ukraine, however. First, Russia does not have the same historical relationship with Finland that it does with Ukraine, and therefore lacks the same imperial ambitions toward Finland as it has in Ukraine. As a result, it might have been more lenient with Finland than it wants to be with Ukraine when it comes to imposing caps on military capabilities. However, Ukraine also has more leverage than Finland did at the end of World War II and can likely avoid the most-severe restrictions that Russia might try to impose. Second, Russia benefited from Finland’s militarization to a degree, because it formed a physical buffer between Russia and the rest of Europe that offered it protection.76Vital, The Survival of Small States; Menon and Snyder, “Buffer Zones”; Lieven, “Restraining NATO.” This also may have worked in Finland’s favor in a way that is unlikely to help Ukraine. Ukraine can only serve a buffer for Russia if Moscow controls Kyiv’s political leadership, which is not the case as of this writing.

Overall, Finland’s Cold War experience offers Ukraine a model that is feasible and would ensure its long-term security, even if it would require that Kyiv accepts a neutral status.

Nonaligned states

As with neutral states, nonaligned states remain outside of formal alliances. But because nonalignment is a policy concept and not a legal status, they have more flexibility in their choices about which types of military activities to pursue. In this sense, it is best to think of nonalignment as operating on a spectrum. States can be nonaligned and have very few security partnerships, or they can be nonaligned and have many types of partnerships and relationships that vary from limited in nature to extensive, including hosting of military forces and participation in military exercises.77Soldatenko, “Exploring Ukraine’s Armed Neutrality or Nonalignment”; Ørvik, Semi-Aligned Security; Mueller, “Alignment Balancing and Stability in Eastern Europe.” If Ukraine adopts a form of nonalignment, its terms are likely to be specific to its circumstance and negotiated jointly with Moscow and U.S. and European partners, so it may not follow any of these models exactly. Still, it is useful to consider what lessons might be offered form the experiences of nonaligned countries.

Vietnam and post-Cold War Finland and Sweden

Some nonaligned states are without alliances or security guarantees. Vietnam, for instance, adopted its nonaligned status willingly, seeing it as the best way to avoid being dragged unwilling into major power wars, especially after the Vietnam War involving the United States and its 1979 war with China.78Yaacob, “Vietnam’s Flexible Nonalignment.” The country’s “four no’s” policy prevents it from taking sides in international conflicts, joining military alliances, hosting foreign forces, or establishing foreign military bases inside Vietnam, and it urges against the use or even threat of force in dealing with other countries.79Shidore, “What the US Can Learn from Vietnam’s Four No’s”; Tuan, “Vietnam Continues ‘Four Nos’ Defense Policy.” Vietnam’s policy does not prohibit military relationships for training or intelligence-sharing with other countries, which Vietnam engages in quite extensively.80Shidore, “What the US Can Learn from Vietnam’s Four No’s”; International Trade Administration, “Vietnam Country Commercial Guide: Defense and Security Sector.” Vietnam has pursued balance, however, forging partnerships with many nations. In 2024, it was the only country to host visits from Chinese President Xi Jinping, Russian President Vladimir Putin, and President Biden.81Le Thu, “Hanoi’s American Hedge”; Schaufelbuehl et al., “Non-Alignment, the Third Force, or Fence-Sitting.” At the same time, without security guarantees or any assistance, Vietnam has built a strong military force and an effective maritime militia to defend its coastal territories from Chinese encroachment.82Parameswaran, “What’s Next for Vietnam’s Maritime Militia?”

Between the end of the Cold War and their entrance into NATO in 2023 and 2024, Finland and Sweden were also formally nonaligned countries: They avoided binding military alliances but they still established a deep connection with NATO and other NATO member states while Vietnam has not aligned with any one security bloc.83Chatterjee, “How Sweden and Finland Went from Neutral to NATO”; Kjellström Elgin and Lanoszka, “Sweden, Finland, and the Meaning of Alliance Membership.” For example, both countries became NATO partners, participated in NATO missions abroad (including Sweden’s participation in NATO operations in Libya), and Sweden agreed to host NATO training exercises.84Chatterjee, “How Sweden and Finland Went from Neutral to NATO”; Kjellström, Elgin, and Lanoszka, “Sweden, Finland, and the Meaning of Alliance Membership”; Egnell, “The Swedish Experience.” As a result, even before NATO membership, these countries had deeply integrated their militaries with NATO. They remained formally nonaligned but benefited in many ways from their position just on the edge of the NATO alliance. Neither Finland nor Sweden would have benefited automatically from Article 5 protection or the assured provision of military or economic assistance had these countries been attacked prior to 2023, but both had at least some expectation of NATO protection because their close integration with NATO members. They would, however, have been covered by the EU’s mutual assistance provision—Article 42.7 of the Lisbon treaty.

Feasibility for Ukraine

A security arrangement similar those that Finland and Sweden had after the Cold War or Vietnam had after 1976 is a model that Ukraine might strive for and one that is likely feasible, to an extent. The approach would leave Ukraine outside major alliances, but allow it to develop the military capabilities needed to defend itself and build significant military partnerships and cooperation with U.S. and European partners.