Key points

- It is often argued that the policies of containment and military deterrence worked against the Soviet threat during the Cold War, and many have urged applying these same policies to China today. However, it is not clear that containment was all that successful during the Cold War nor is it clear that it should now be applied to China.

- Should it pursue the “hegemonic” ambitions often attributed to it, China, like the USSR, may prove its own worst enemy by overstretching its resources and provoking its neighbors.

- In any case, China does not seem to harbor hegemonic ambitions. Its existing gestures at global influence, like the Belt and Road Initiative, are in disarray and unlikely to work.

- Rather than rushing to more forcefully contain or balance China, the United States should let China make its own mistakes. Doing nothing or next to nothing against a perceived threat isn’t always wise or politically popular but in this case it’s the most rational choice.

- The U.S. can wait for China to mellow while warily profiting from China’s economic size and problems to the degree possible and expanding mutually beneficial exchange. The U.S. can also help Taiwan prepare to defend itself while maintaining that the island is independent so long as it doesn’t say so.

Introduction

It is often argued that the policy of containment and the related policy of military deterrence worked against the Soviet threat during the Cold War. Diplomat Chas Freeman declares that containment “brought us a bloodless victory in the Cold War,” while Daniel Drezner characterizes it as “persistently effective” and Scott Sagan substantially agrees.1Chas W. Freeman Jr., “The United States and China: Game of Superpowers,” Middle East Policy Council, February 8, 2018, mepc.org/speeches/united-states-and-china-gamesuperpowers. Daniel W. Drezner, “This Time is Different: Why U.S. Foreign Policy Will Never Recover,” Foreign Affairs, May/June 2019, 11. Scott D. Sagan, “The Korean Missile Crisis,” Foreign Affairs, November/December 2017, 82.

Many want to apply these same policies to China today. For example, Hal Brands urges that this “elegant” and “winning” Cold War strategy can work against China too: “to succeed against a rising China, the U.S. must relearn the lessons of containment,”2Hal Brands, “Containment Can Work Against China, Too,” Wall Street Journal, December 3, 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/containment-can-work-against-china-too-11638547169. or in Aaron Friedberg’s words, “relearn the lessons of the 1940s and 1950s.”3Aaron L. Friedberg, Getting China Wrong (Medford, MA: Polity Press, 2022), 195. Michael Mandelbaum deems containment to have been a “success” during the Cold War and argues that it should be applied “once again, now to Russia, China, and Iran,” although “modified and updated.”4Michael Mandelbaum, “The New Containment: Handling Russia, China, and Iran,” Foreign Affairs, March/April 2019, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2019-02-12/new-containment.

However, it is not clear that containment was all that successful during the Cold War. Nor is it clear that a similar policy should be applied to China today. In fact, containment is given too much credit for winning the Cold War: the errors and weaknesses of the USSR largely caused its downfall. U.S. foreign policy during the Cold War did too much, not too little. And like the USSR, China today could be its own worst enemy. The key is to let China, which is perhaps stagnating and even declining, make its own mistakes. Military policies seeking to “balance” against the rise of China scarcely seem necessary given the present circumstances.

Containment in the Cold War

The quintessential intellectual presentation of containment policy remains George Kennan’s article “The Sources of Soviet Conduct,” published in Foreign Affairs in July 1947.5George F. Kennan, “The Sources of Soviet Conduct,” Foreign Affairs, July 1947, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/russian-federation/george-kennan-sources-soviet-conduct, 566–82. While concerned about Soviet military strength, it argued that what made that strength threatening was an ideology that was fundamentally expansionist.

Accordingly, Kennan contended that the “main element” of U.S. policy “must be that of a long-term, patient but firm and vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies,” particularly by preventing other countries from joining the communist camp. Kennan concluded that, in time, this might work because there was a “strong” possibility that Soviet power “bears within it the seeds of its own decay, and that the sprouting of these seeds is well advanced.” These “seeds” included the exhaustion and disillusionment of the Soviet population, “spotty” economic development, the difficulty of maintaining control over the peoples of Eastern Europe, and the looming uncertainties in the impeding transfer of power that would follow the death of Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin—something, suggested Kennan, that might “shake Soviet power to its foundations.”

Eventually, Kennan hoped, the Soviets, frustrated in their drive for expansion, which he deemed to be primarily ideological, would become less hostile and more accommodating.

How long it might take for this to happen was not predictable, of course, but Kennan opined that it might take 10 to 15 years. He strongly suggested that he was putting his primary emphasis on the transfer of power issue: Stalin was nearing 70 at the time.

As it turned out, the Soviet regime managed to survive Stalin’s death (which took place in 1953), and for decades was able to maintain its control at home and over the countries it occupied.

The limited success of containment in the Cold War

The policy of containment as articulated by Kennan seems to have prevented few countries from embracing communism during the Cold War. It may have made some difference here and there, but determining whether some of containment’s perceived successes—as with Marshall Plan aid, which was supposed to keep countries in Western Europe from embracing communism, or with U.S.-backed coups in Guatemala and Iran in 1954—prevented left-leaning countries from tipping into the communist camp would be difficult. The record of success at covert or overt regime change is very limited.6Lindsey A, O’Rourke, Covert Regime Change: America’s Secret Cold War (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018). Philip H. Gordon, Losing the Game: The False Promise of Regime Change in the Middle East (New York: St. Martin’s, 2020).

The clearest case of the policy’s success was military: turning back the invasion of South Korea by communist North Korea in 1950 in a war that then became much more costly and ended in stalemate. At the time, the invasion, as defense analyst Bernard Brodie notes, was almost universally held to be part of a grand Soviet scheme to dominate the world and an invasion of Western Europe was seen as imminent.7Bernard Brodie, War and Politics (New York: Macmillan, 1973), 63–64. Instead it was simply an opportunistic foray in a then-remote part of the globe.8William Stueck, Rethinking the Korean War: A New Diplomatic and Strategic History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002), 70–75. Nikita Khrushchev, Khrushchev Remembers, ed. Edward Crankshaw and Strobe Talbott (Boston: Little, Brown, 1970), 367–68.

With the Korea venture, however, containment policy became much more military, a development that Kennan viewed with dismay. Central to this was military deterrence, even though there seems to be no evidence that the Soviets needed to be deterred. Although they did seek to aid and inspire revolutionary movements around the world,9Historicus [George Allen Morgan], “Stalin on Revolution,” Foreign Affairs, January 1949, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russian-federation/1949-01-01/stalin-revolution, 198. they never had an interest in waging anything like a repeat of World War II.10For an extended discussion of this point, see John Mueller, The Stupidity of War (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2021), chs. 1 and 2, and especially 34–41.

Thus in 1977 Kennan argued that the Soviet Union “has no desire for any major war, least of all for a nuclear one. …Plotting an attack on Western Europe would be… the last thing that would come into its head.” Later in the Cold War, he wrote, “I have never believed that they have seen it as in their interests to overrun Western Europe militarily, or that they would have launched an attack on that region generally even if the so-called nuclear deterrent had not existed.”11George F. Kennan, The Cloud of Danger: Current Realities of American Foreign Policy (Boston: Little, Brown, 1977), 200; “Containment Then and Now,” Foreign Affairs, Spring 1987, 888–87. In contrast, Matt Pottinger holds that “what kept the Cold War cold in the last century” was “unmistakable strength in the form of military hard power.” “‘The Stormy Seas of a Major Test’,” in Matt Pottinger ed., Boiling Moat: Urgent Steps to Defend Taiwan (Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 2024), 18.

After researching the Soviet archives after the Cold War, historian Vojtech Mastny concluded that “All Warsaw Pact scenarios presumed a war started by NATO” and that “The strategy of nuclear deterrence [was] irrelevant to deterring a major war that the enemy did not wish to launch in the first place.”12Vojtech Mastny, “Introduction” and “Imagining War in Europe” in Vojtech Mastny, Sven G. Holtsmark, and Andreas Wenger, eds., War Plans and Alliances in the Cold War: Threat Perceptions in the East and West (London and New York: Routledge, 2006), 3, 27.

Kennan had few allies in his views (though President Dwight Eisenhower seems privately to have reached much the same position).13John Mueller, The Stupidity of War (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 35–38; on Eisenhower, 39–40. Instead, as with China today, there was a determined focus on the “arms race” in which any seeming or real Soviet arms gains were seen as alarmingly threatening. The ultimate development of this was the “missile gap” frenzy of the late 1950s in which the Soviets were deemed likely to soon have hundreds of intercontinental ballistic missiles. The actual number proved to be four.

It is worth noting that containment policy played little role in three of international communism’s major setbacks during the Cold War: each was substantially self-inflicted. In 1948, Stalin sought and failed to bring Yugoslavia, led by a loyal but independent communist party, under tighter control. In 1965, there was a violent crackdown against China-linked communists who were attempting a coup in Indonesia, an important potential domino at the time, undercutting a key justification for the earlier entry of the United States into Vietnam.14John Mueller, “Reassessment of American Policy, 1965–1968,” in Harrison E. Salisbury (ed.), Vietnam Reconsidered: Lessons from a War (New York: Harper & Row, 1984), 48–52. And erupting in the 1960s, the communist movement was damagingly split by a self-induced and self-destructive theological dispute between China and the Soviet Union that effectively drove China out of the Cold War and into the embrace of the United States.15John Mueller, Overblown: How Politicians and the Terrorism Industry Inflate National Security Threats, and Why We Believe Them (New York: Free Press, 2006), 100. John Mueller, Retreat from Doomsday: The Obsolescence of Major War (New York: Basic Books, 1989), ch. 8.

In the end, any mellowing of Soviet expansionism was due not so much to containment’s success as to its failure. In fact, if the Soviet system was as rotten to the core as Kennan argued, logic might have dictated not containing it but letting it expand so that it might more readily self-destruct. To a degree, that actually happened. In 1975, Cambodia, South Vietnam, and Laos abruptly fell into the communist camp. Partly out of fear of repeating the Vietnam experience, the United States went into a sort of containment funk, so-called “Vietnam syndrome.” The Soviet Union, in what seems in retrospect to have been like a fit of absentmindedness, gathered willing third-world countries into its embrace: Angola in 1976, Mozambique and Ethiopia in 1977, South Yemen and Afghanistan in 1978, Grenada and Nicaragua in 1979.

At first, the Soviets were quite gleeful about these acquisitions—the “correlation of forces,” as they called it, had agreeably shifted in their direction.16George W. Breslauer, “Ideology and Learning in Soviet Third World Policy,” World Politics 39 (3) April 1987, 436–37. Robert Jervis, “Was the Cold War a Security Dilemma?” Journal of Cold War Studies 3 (1) Winter 2001, 50. However, almost all the new acquisitions soon became economic and political basket cases, fraught with dissension, financial mismanagement, and civil warfare, and turned expectantly to the Soviet Union for maternal warmth and sustenance. Most disastrous for the Soviets was the experience in Afghanistan. In December 1979, they sent a large contingent of troops there to establish order and quash an anti-communist rebellion and soon found themselves bogged down in a protracted war.

The Soviets would come to realize they would have been better off contained.

Containment and the breakup of the Soviet Union

Containment policy hardly caused the breakup of the Soviet Union in late 1991. Indeed, by that time, the United States had long deemed the Cold War to be over and had officially deserted containment.

It took 40 years for the Soviets, plagued by economic, social, and military disasters, to abandon their ideology as Kennan had hoped. The process culminated in a speech made by Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev at the United Nations in late 1988 in which he called for “de-ideologizing relations among states.” As George Shultz, the secretary of state at the time, recollected a few years later, “If anybody declared the end of the Cold War, he did in that speech.”17William C. Wohlforth, ed., Witnesses to the End of the Cold War (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), 91.

By the spring of 1989, at a time when the USSR was still fully communist, possessed a large military, and still controlled most of Eastern Europe, that conclusion had been accepted by the new George H. W. Bush administration. In a series of speeches about going “beyond containment,” Bush announced that the goal was now to integrate “the Soviet Union into the community of nations” and to welcome it “back into the world order.”18John Mueller, “What Was the Cold War About? Evidence from Its Ending,” Political Science Quarterly 119 (4) Winter 2004–05, 609-31. John Mueller, War and Ideas (New York: Routledge, 2011), ch. 5.

In 1989 and 1990, Eastern European states left the military alliance that had been forced on them by the Soviets (thereby reducing Soviet costs) and worked their way toward democracy, capitalism, and Europe.19On this remarkable development, see John Mueller, Capitalism, Democracy, and Ralph’s Pretty Good Grocery (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999), 103–04, 219–22. The U.S. welcomed this change, but it also made considerable effort to keep the Soviet Union itself from collapsing. Most notably, concerned in 1991 about the armed disintegration of another communist federation, Yugoslavia, Bush gave a speech in Ukraine in which he essentially urged the various Soviet Republics to work it out and remain within the country.20Michael R. Beschloss and Strobe Talbott, At the Highest Levels: The Inside Story of the End of the Cold War (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1993), 417–18. If there was a Cold War raging at that time, Bush’s United States and Gorbachev’s Soviet Union were on the same side.

Shortly after Bush’s speech, however, communist hardliners, intent on keeping the Soviet Union from falling apart, attempted a coup against Gorbachev. It failed miserably, but it shifted sentiment (particularly in Ukraine) and resulted in exactly the kind of breakup the conspirators were seeking to prevent.21Andrew Wilson, Ukrainians: Unexpected Nation (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009), 165–69. Mark Kramer, “The Dissolution of the Soviet Union,” Journal of Cold War Studies 24 (1) Winter 2022, 201–04. Without that development, it is possible that, with some economic reform, including defense spending cuts, the Soviet Union might have been able to survive more or less intact.22Myron Rush, “Fortune and Fate,” National Interest, Spring 1993, 19–25. Mark Kramer, “The Dissolution of the Soviet Union,” Journal of Cold War Studies 24 (1) Winter 2022, 207–11. Max Boot, “Reagan Didn’t Win the Cold War: How a Myth About the Collapse of the Soviet Union Leads Republicans Astray on China,” Foreign Affairs, September 6, 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/reagan-didnt-win-cold-war.

As analyst Strobe Talbott put it at the time, the Soviet system went “into meltdown because of inadequacies and defects at its core, not because of anything the outside world had done or threatened to do.” Historian Odd Arne Westad agrees: the USSR collapsed primarily “because of weaknesses and contradictions in the Soviet system itself.”23Strobe Talbott, “Remaking the Red Menace,” Time, January 1, 1990, https://time.com/archive/6713848/rethinking-the-red-menace/. Odd Arne Westad, “The Sources of Chinese Conduct: Are Washington and Beijing Fighting a New Cold War?” Foreign Affairs, September/October 2019, 86. See also Boot, “Reagan Didn’t Win the Cold War.”

The American military threat may have partly impelled the Soviets to overbuild in defense, but they might well have done that anyway given Soviet—or even historically Russian—suspicion of the outside world. And, of course, containment did not cause the Soviets to adopt their stifling economic and bureaucratic system, to get involved in a costly and demoralizing war in Afghanistan, or to take on their array of dependencies in Africa, Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Eastern Europe. But containment did assume that the threatening Soviet dynamic would eventually self-destruct in one way or another, and to a considerable degree the essential contradictions of the Soviet system and ideology finally did catch up with it.

Containment and China

It appears, then, that it was largely unnecessary to do much of anything—especially militarily— to deal with the threat or challenge once deemed to be presented by the Soviet Union. And perhaps something like that holds true today for policy toward China. In particular, military policies seeking to “balance” against the rise of China scarcely seem more necessary than they were for the Soviet challenge during the Cold War.

China doesn’t present the same kind of ideological challenge as the Soviet Union. It has sought to aid other authoritarian kleptocracies to better maintain their hold on power, but that is hardly an expansion of ideology. Moreover, it does not seem to have much in the way of territorial ambitions beyond reincorporating Taiwan at some point and settling disputes over parts of its border and over issues concerning the South China Sea.24Kishore Mahbubani, Has China Won? The Chinese Challenge to American Primacy (New York: PublicAffairs, 2020). For the argument that much of the conflict in the South China Sea is over fish, see John Mueller, “China: Rise or Demise?” Policy Analysis no. 917, Cato Institute, May 18, 2021, https://www.cato.org/policy-analysis/china-rise-or-demise, 8.

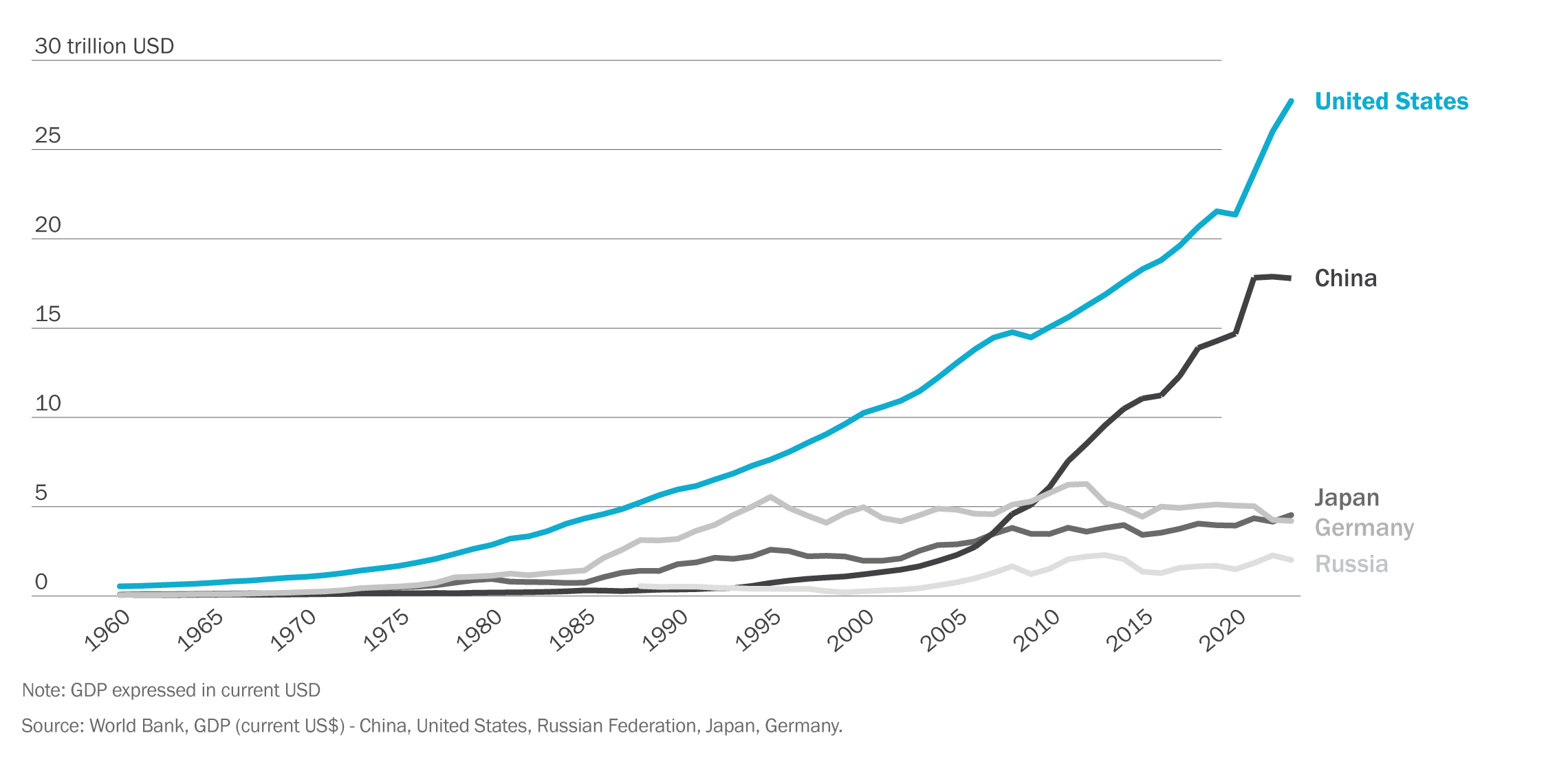

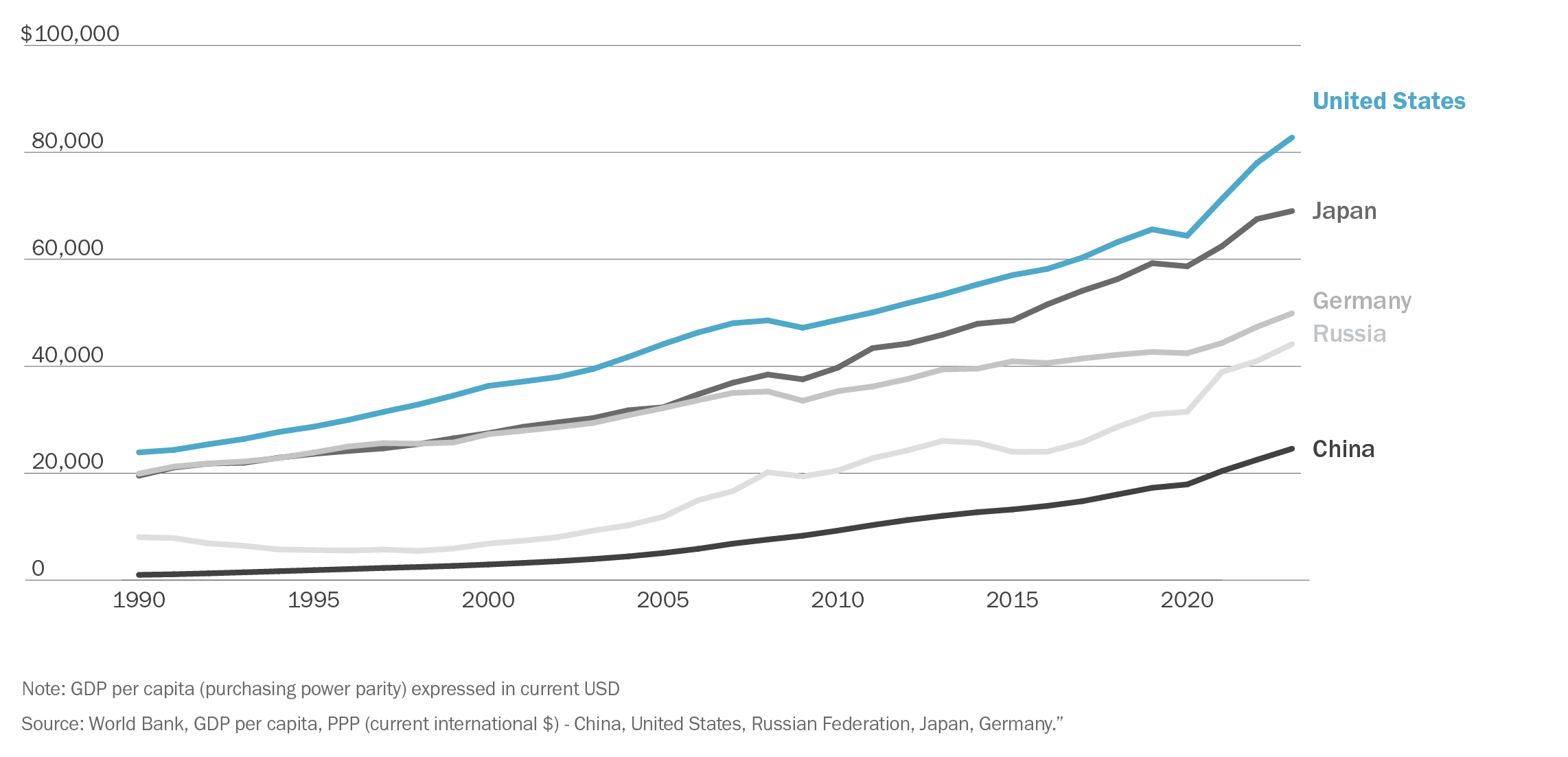

However, because of its size and economic growth, China is now in second place in total GDP (though seventy-eighth in per capita GDP), a position it has occupied for most of the last two millennia.25For data, see Mueller, “China: Rise or Demise?” 3. Partly impelled by that development, it does seem to be seeking a more central spot in global politics and wants to be taken seriously as a “great power.” In 2012, as he was becoming the paramount leader in China—a position he still holds—Xi Jinping proclaimed that “We must achieve the great revival of the Chinese nation, and we must ensure there is unison between a prosperous nation and a strong military.”26Orville Schell and John Delury, Wealth and Power: China’s Long March to the Twentieth Century (New York: Random House, 2013), 403.

GDPs of top economies since 1960

China has the second largest GDP of any nation, though not per capita.

John Mearsheimer of the University of Chicago is among those who, alarmed at China’s rise, have deemed it important that the United States keep China in check. Mearsheimer considers this one of a very few core strategic interests for which the United States should use force.27John J. Mearsheimer, “America Unhinged,” National Interest, January/February 2014, 12, 26, 30. As he puts it bluntly, the U.S. “must prevent China from becoming a hegemon in Asia.”28John J. Mearsheimer, The Great Delusion: Liberal Dreams and International Realities (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018), 228.

In a globalized economy, it is, of course, better for the United States and just about everyone if China (or Japan or Brazil or India or any other country) becomes more prosperous.29On this issue, see Charles Kenny, The Upside of Down: Why the Rise of the Rest is Good for the West (New York: Basic Books, 2013). For one thing, a wealthier China means the Chinese can buy more foreign goods and services—and debt. However, eschewing such economic logic, observers often perceive a threat in China’s rapidly increasing wealth and military buildup.

There is considerable literature arguing that by a string of measures the United States will remain by far the strongest country in the world for decades to come.30Stephen G. Brooks and William G. Wohlforth, World Out of Balance: International Relations and the Challenge of American Primacy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008). Michael Beckley, Unrivaled: Why America Will Remain the World’s Sole Superpower (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018). Nonetheless, writing with Harvard University’s Stephen Walt, Mearsheimer argues that the chief concern is the rise of a “hegemon” that would “dominate” its region, much as the United States is said to dominate the Western Hemisphere. Such a state would have abundant economic clout, the ability to develop sophisticated weaponry, the potential to project power around the globe, and perhaps the wherewithal to outspend the United States in an arms race. It might even ally with countries in the Western Hemisphere and interfere close to U.S. soil.31John J. Mearsheimer and Stephen M. Walt, “The Case for Offshore Balancing: A Superior U.S. Grand Strategy,” Foreign Affairs, July/August 2016, 70–83.

The United States as ‘hegemon’

“Hegemony” is an extreme word suggesting supremacy, mastery, and full control. Hegemons force others to bend to their will whether they like it or not.32See also Simon F. Reich and Richard Ned Lebow, Good-Bye Hegemony! Power and Influence in the Global System (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014).

Overall, however, there’s little in the record to inspire would-be “hegemons.” For an apt comparison, it may be useful to assess a quintessential case: the American experience with hegemony in its hemisphere from 1860 to 1945. Sean Mirski has done so.33Sean Mirski, We May Dominate the World: Ambition, Anxiety, and the Rise of the American Colossus (New York: PublicAffairs, 2023). For a more extended discussion of this book, see John Mueller, “The Perils of the Hegemon,” Cato at Liberty blog, Cato Institute, November 10, 2023, www.cato.org/blog/perils-hegemon. His assessment can be taken to suggest that “domination” is filled with peril, resistance, and disappointment; is something of a fantasy; and is scarcely worth the effort. Prospective hegemons like China might best be advised to avoid this course altogether.

By the early twentieth century, notes Mirski, the U.S. “hegemon” found itself “battling monsters, real and imagined” throughout the hemisphere in a series of misadventures primarily designed to get and keep the unruly Latin Americans under control. These included “occupying two entire nations, garrisoning parts of three more, running half a dozen protectorates and customs receiverships, prosecuting several bloody counterinsurgencies, and deposing regimes with a frequency that bordered on the gratuitous.”34For example, in 1915, a mission was sent to Haiti after what Mirski calls its “tinpot dictator” was killed by an angry mob. This led to a costly and chaotic occupation that lasted until 1934, after which the country devolved back to what seems more or less like what had existed before. An earlier enterprise in 1903 was more successful. In the 60 years prior, revolutionists in the province of Panama had sought at least 50 times to secede from Colombia, and the United States had often helped Colombia put those rebellions down. By 1903, however, the U.S. had become anxious to get a canal built there after a French effort had gone bankrupt, and was frustrated with negotiations with Colombia. Accordingly, the United States switched sides. An amazingly inept expeditionary force sent by Colombia to counter the secessionist effort was readily bribed into submission. In the end, however, Mirski deems the American caper to have been unnecessary and a “blunder.” Mirski, We May Dominate the World, 156. Occupying American soldiers were mainly despised (except by artful local opportunists seeking to manipulate the interventions to their own advantage) and learned to walk down the middle of streets to better dodge the garbage hurled at them by undominated locals.35Mirski, We May Dominate the World, 2, 285, 290.

But Mirski also argues that U.S. interventions did manage to succeed at one hegemonic task: keeping other great or potentially great powers out of the hemisphere. Most notably, the U.S. helped to further derail bungled probes by the French before and during the American Civil War and by Germany in the run-up to America’s entry into World War I, and it annexed the Hawaiian Islands in 1898 to counter Japan’s influence there. Acting mostly out of humanitarian motives, the hegemon also ousted colonial Spain from Cuba in a war in 1898.36Actually many Spaniards welcomed the war because a defeat would have allowed them to withdraw honorably from their highly troublesome colony. Melvin Small, Was War Necessary? National Security and U.S. Entry into War (Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE Publications, 1980). Robert Jervis, Richard Ned Lebow, and Janice Gross Stein, Psychology and Deterrence (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985). In the process, the U.S. also snapped up the Philippines.

However, for the most part, foreign powers sought to intervene in Latin America not to undermine American “hegemony” but to collect debts and to protect their nationals residing there. Indeed, the wily Europeans were sometimes able to snooker the alarmed Americans into doing this work for them.37Mirski, We May Dominate the World, 174¬–175.

Nonetheless, the Americans found (or imagined) any European efforts to be threatening, and became obsessed with Latin American corruption and disorderliness, weaknesses that might allow for the reentry of one European rival or another. Yet Mirski finds that “time and again” intervention by the great northern dominator “would miscarry, leading to greater instability” and presumably leaving Latin America more vulnerable to intervention by the dreaded Europeans.38Mirski, We May Dominate the World, 12. Actually it seems likely that the European rivals never got around to reinserting themselves not so much because of American “hegemony” but because they were fully consumed with other tasks: colonizing Africa and Asia, and misdealing with each other in a manner that led to two massive wars on their continent.

Eventually, the U.S. substantially abandoned this policy and came to rely instead on soft power to deal with the unruly Latins, an approach labeled the “Good Neighbor Policy.” There were occasional reversions to earlier methods, but these generally failed. Thus, the hegemon used force in Cuba where it tried and failed to topple a communist regime that emerged there in 1959. Efforts at subversion have also failed, and the Cuban government has been thumbing its nose at the hegemon for 65 years.39As the Cato Institute’s Doug Bandow notes, “the world’s greatest power has proven incapable even of replacing the hostile government of a small island almost within sight of its coast.” Doug Bandow, “Blame America Too for Our Ruptured Relations with the Chinese,” American Conservative, July 4, 2019, emphasis in the original. The United States also applied sanctions with, as usual, no positive policy result (the same would later hold true with Venezuela).40On the futility of economic sanctions to change policy, see Richard Hanania, “Ineffective, Immoral, Politically Convenient: America’s Overreliance on Economic Sanctions and What to Do About It,” Policy Analysis no. 884, Cato Institute, February 18, 2020, https://www.cato.org/policy-analysis/ineffective-immoral-politically-convenient-americas-overreliance-economic-sanctions; Murat Sofuoglu and Melis Alemdar, “Have US-Imposed Sanctions Ever Worked?” interview with Gary Hufbauer, trtworld.com, September 24, 2018, https://www.trtworld.com/magazine/have-us-imposed-sanctions-ever-worked-20428. The hegemon also can’t seem to stop the inflow of drugs from its south or of guns going the other way.41The chief hegemonic success story of late (besides, perhaps, keeping Soviet weapons that are potentially offensive out of Cuba), was the use of military force that successfully reimposed democracy when it lapsed in tiny Panama in 1989 and even tinier Grenada in 1983. Military interventions had routinely failed earlier in the century. This time, however, they worked: democracy resumed after the Americans left.

Although the United States sometimes got its way in Latin America, it is absurd to think that, even under ideal “hegemonic” conditions, it “dominated” by any reasonable definition of that extreme word.

China as ‘hegemon’

If the United States could not really dominate the insecure countries in its neighborhood during its hegemonic century, it seems unlikely that a hegemonic China could do much better in its area. As Mirski notes, many of the countries in China’s neighborhood are far more secure and better equipped than the Latins of yore, particularly Japan, South Korea, India, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Australia.42Mirski, We May Dominate the World, 347. In addition, unlike their Latin American counterparts, they would probably seek to coordinate with each other and with the ever-lurking United States against a China threat—some of this has already happened.43See also Stephen M. Walt, “Stop Worrying About Chinese Hegemony in Asia,” Foreign Policy, May 31, 2023, https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/05/31/stop-worrying-about-chinese-hegemony-in-asia/; Michael Schuman, Superpower Interrupted: The Chinese History of the World (New York: PublicAffairs, 2020), 316–17. Like the Latins, they would evade diktats issued by their large and increasingly despised neighbor.

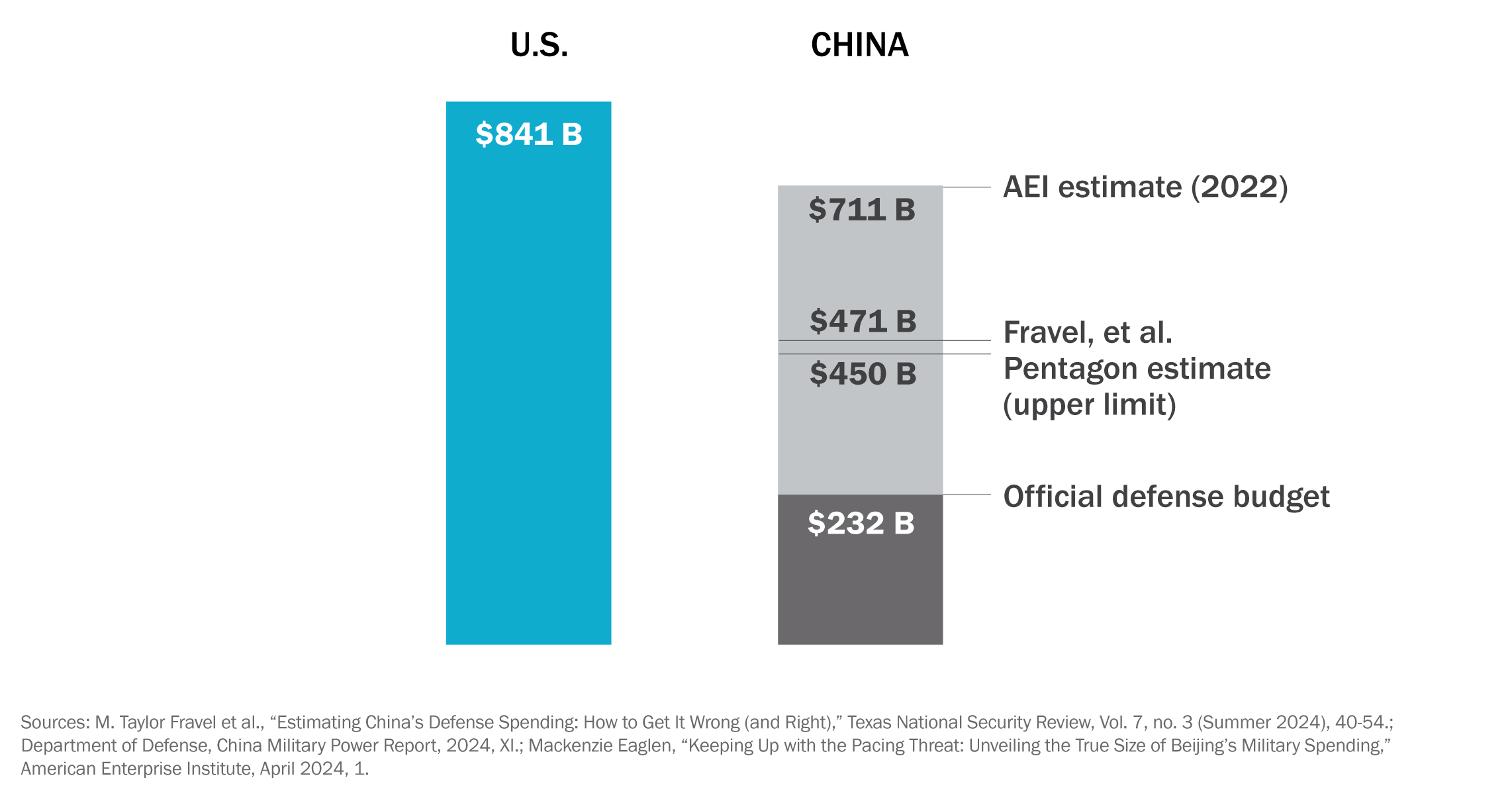

United States vs. China defense spending

A recent report by the bipartisan Commission on the National Defense Strategy deems the “most formidable military threat” today to be the one presented by China.44Jane Harman et al, “Commission on the National Defense Strategy,” July 2024, https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/nds_commission_final_report.pdf, 5. There are great concerns about its defense buildup, and the report cites estimates that China’s defense budget is now comparable to that of the U.S., although it does acknowledge in a footnote that other estimates are far lower.45For that estimate, see M. Taylor Fravel, George J. Gilboy, and Eric Heginbotham, “Estimating China’s Defense Spending: How to Get It Wrong (and Right),” Texas National Security Review 7 (3) Summer 2024. It should be added that, although China’s military buildup has included its gaining of a few bases in the Middle East, these seem designed to help maintain the sea lanes so vital to China’s development.46Nathan Beauchamp-Mustafaga and Howard Wan, “The Threat From Overseas Chinese Military Bases Is Overblown,” Diplomat, July 30, 3024, https://thediplomat.com/2024/07/the-threat-from-overseas-chinese-military-bases-is-overblown/; Mike Sweeney, “Challenges to China’s Blue Water Operations,” Defense Priorities, April 30, 2024, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/challenges-to-chinese-blue-water-operations/. As in the Cold War, arms race alarm seems unjustified.

While any Chinese quest for full-blown “hegemony” may be ill-advised and perhaps doomed, China is also seeking to gain “influence” in somewhat more subtle ways by lending money via its Belt and Road Initiative to a vast array of other countries and by engaging from time to time in “wolf warrior diplomacy,” using economic and military muscle to badger and to bully. However, these efforts have been remarkably futile and counterproductive.

Rather than inspiring admiration or obedience, resentment at China’s “wolf warrior” antics has soared not only in the West but also in important neighbors like Japan, South Korea, India, Vietnam, Indonesia, Australia, and, most significantly, Taiwan. Some of these countries have even been pushed further into the embrace of the United States.47Hal Brands and Michael Beckley, Danger Zone: The Coming Conflict with China (New York: Norton, 2002), 12, 68–73, 125–26. Some elements of China’s counterproductive “wolf warrior” diplomacy have since been relaxed.48Fareed Zakaria, “In 2024, U.S. domestic politics will cast a dark shadow across the world,” Washington Post, December 15, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2023/12/15/us-dysfunction-chaos-china-russia-hamas/. Shaoyu Yuan, “Goodbye, Wolf Warrior: Charting China’s transition to a more accommodating diplomacy,” International Affairs 100 (5) 2024, 2217–32.

China’s much-touted Belt and Road Initiative is awash in unpaid debt and loan outlays were cut from $75 billion in 2016 to $4 billion in 2019.49James Kynge and Jonathan Wheatley, “China pulls back from the world: rethinking Xi’s ‘project of the century’,” Financial Times, December 11, 2020, https://www.ft.com/content/d9bd8059-d05c-4e6f-968b-1672241ec1f6. Michael Bennon and Francis Fukuyama, “China’s Road to Ruin: The Real Toll of Beijing’s Belt and Road,” Foreign Affairs, September/October 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/belt-road-initiative-xi-imf. See also Dmitri Alperovitch with Garrett M. Graff, World on the Brink: How America Can Beat China in the Race for the Twenty-First Century (New York: PublicAffairs, 2024), 163–67. As former national security advisor Condoleezza Rice recently observed, “The BRI is often depicted as helping China win hearts and minds, but in reality it is not winning anything” as recipients grow “frustrated with the corruption, poor safety and labor standards, and fiscal unsustainability associated with its projects.”50Condoleezza Rice, “The Perils of Isolationism: The World Still Needs America—and America Still Needs the World,” Foreign Affairs, September/October 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/perils-isolationism-condoleezza-rice.

The Chinese desire to be treated with respect and deference hardly seems to present a threat. Moreover, if the United States can continually declare itself to be the one indispensable nation (suggesting that other nations are, well, dispensable), why should other countries be denied the opportunity to wallow in such self-important, childish, inconsequential, essentially meaningless, and fatuous proclamations?

Taiwan

Many are particularly exercised by the “critical” threat presented by China’s potential future invasion of Taiwan. They see an invasion as China’s first salvo to “assert dominance” in East Asia51Harman et al, “Commission on the National Defense Strategy,” 5, 7. or as an effort to “grab regional primacy as a springboard to global power” and to “project power into the Pacific, blockade Japan and the Philippines, and fracture U.S. alliances in East Asia.”52Hal Brands and Michael Beckley, Danger Zone: The Coming Conflict with China (New York: Norton, 2002), 125, 129. How this process would be carried out is not made clear, and the idea that seizing Taiwan might well make it more, not less, difficult for further expansion is not addressed.53For skeptical commentary on this issue, see Nick Sweeney, “How Militarily Useful Would Taiwan be to China?” Defense Priorities, April 12, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/how-militarily-useful-would-taiwan-be-to-china/. It might also be pointed out that, in the contingency considered by some analysts to be “most likely,” the military conquest of Taiwan would require China to outdo Pearl Harbor by raining thousands of missiles not only on Taiwan but American military bases and ships in Japan and Guam. Hal Brands and Michael Beckley, Danger Zone: The Coming Conflict with China (New York: Norton, 2002), 135. This would scarcely ease China’s problems in expanding beyond Taiwan.

Xi has given his military the goal of being able to successfully invade Taiwan by 2027, which has been taken by many in the West to be ominously threatening.54Noah Robertson, “How DC became obsessed with a potential 2027 Chinese invasion of Taiwan,” Defense News, May 7, 2024, https://www.defensenews.com/pentagon/2024/05/07/how-dc-became-obsessed-with-a-potential-2027-chinese-invasion-of-taiwan/. However, Timothy Heath of RAND points out that Xi was seeking primarily “to keep the military focused on its goal of becoming more professional and resist tendencies of slipping into corruption and lethargy.” Heath says there appears to be no evidence of an intent to invade in anything like the immediate or not-so-immediate future.55Timothy R. Heath, “Is China Planning to Attack Taiwan? A Careful Consideration of Available Evidence Says No,” War on the Rocks, December 14, 2022, https://warontherocks.com/2022/12/is-china-planning-to-attack-taiwan-a-careful-consideration-of-available-evidence-says-no/. See also Timothy R. Heath, “Is China Prepared for War?” testimony presented to the U.S.-China Economic and Security Committee, June 13, 2024, www.rand.org/pubs/testimonies/CTA3381-1.html; Jessica Chen Weiss, “Don’t Panic About Taiwan: Alarm Over a Chinese Invasion Could Become a Self-Fulfilling Prophecy,” Foreign Affairs, March 21, 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/taiwan-chinese-invasion-dont-panic. Xi himself is reported to be exasperated at the claim and insists that plans to invade in 2027 (or for that matter in 2035) simply do not exist.56Noah Robertson, “How DC became obsessed…”

The problems attendant on a massive amphibious attack from a tempestuous sea are likely to be sobering to Chinese military planners. Not only is such a venture likely to be as “economically devastating” to China as the bipartisan Commission on the National Defense Strategy acknowledges, but there is great difficulty, emphasized by many in the military, in a massive amphibious landing that would require thousands of drone-vulnerable ships. In addition, stormy seas and weather rule out landings much of the year, and major landing beaches are few and well-fortified. In addition, resistance in the form of guerrilla and urban warfare by some of the 20 million intensely hostile residents could prove to be extensive: the island’s interior is mountainous with many tunnels and narrow passes that could be mined or closed by bombs or snipers.57William Spaniel, “What Everyone Gets Wrong about China Invading Taiwan,” YouTube, August 3, 2024, www.youtube.com/watch?v=8eO4zQew4CA. Mueller, “China: Rise or Demise?” 9. Matt Pottinger, “‘The Stormy Seas of a Major Test’,” in Matt Pottinger (ed.), Boiling Moat: Urgent Steps to Defend Taiwan (Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 2024), 10–11. David Sacks, “Why China Would Struggle to Invade Taiwan,” Council on Foreign Relations, New York, June 12, 2024, www.cfr.org/article/why-china-would-struggle-invade-taiwan. Lonnie Henley, “Many Ways to Fail: The Costs to China of an Unsuccessful Invasion,” U.S. Institute of Peace, November 5, 2024, www.usip.org/publications/2024/11/many-ways-fail-costs-china-unsuccessful-taiwan-invasion.

The judgment of the CIA in 2023, according to its director William Burns, is that “President Xi and his military leaders have doubts today about whether they could accomplish that invasion” and that “if they look at Putin’s experience in Ukraine, that’s probably reinforced some of those doubts.”58Face the Nation, “CIA Director William Burns on “Face the Nation with Margaret Brennan” | full interview,” YouTube, February 16, 2023, at 17 minutes, www.youtube.com/watch?v=HN4bgqKq2MU. On Putin’s folly in Ukraine, see John Mueller “The Upside of Putin’s Delusions,” Foreign Affairs, August 2, 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/russian-federation/upside-putins-delusions; Rajan Menon, “Putin Has Already Lost,” New York Times, February 22, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/02/22/opinion/russia-ukraine-invasion-putin.html; Rajan Menon, “Putin’s Victory Will Be a Hollow One,” Foreign Policy, January 13, 2025, https://foreignpolicy.com/2025/01/13/russia-ukraine-war-putin-military-strategy-victory-settlement-territory/. Indeed, impelled by such considerations, longtime diplomat and China-watcher Ambassador Winston Lord has concluded that the chances of an invasion of Taiwan in the next decade or two are “somewhere between one and two percent.”59Asia Society, “China and Taiwan: Will it Come to Conflict?” YouTube, July 1, 2024, at 39 minutes, www.youtube.com/watch?v=v5CH4mFGNXk.

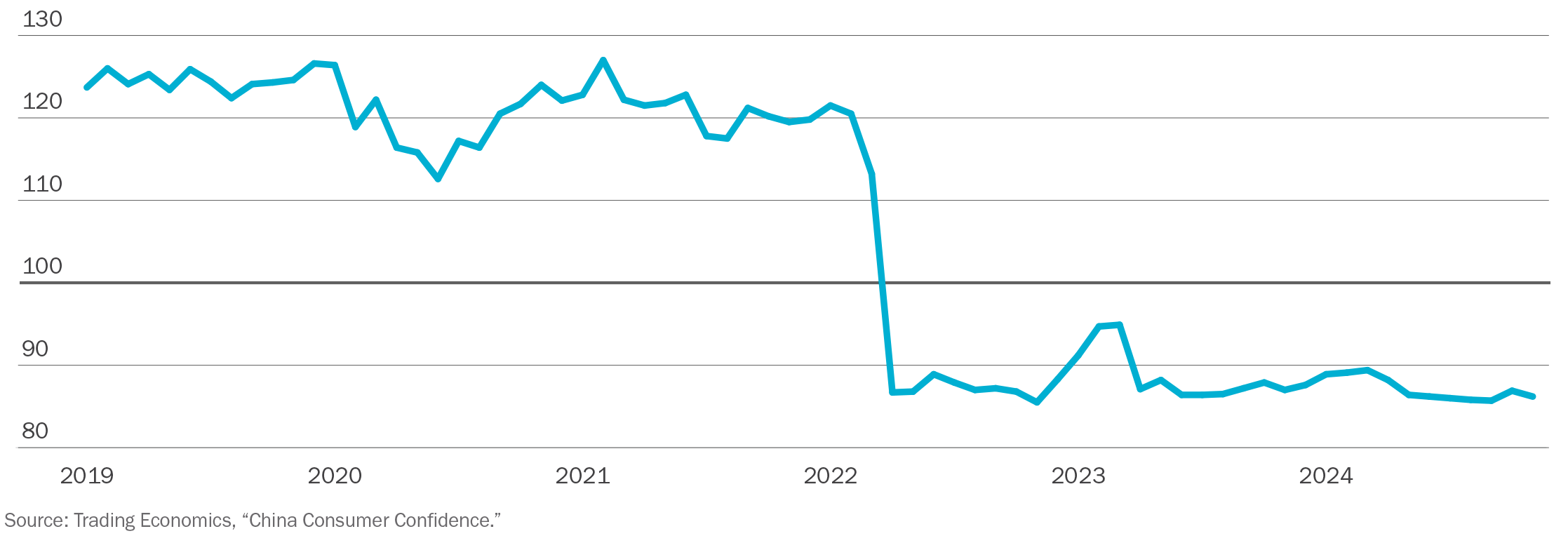

The potential for, and relevance of, Chinese decline or stagnation

Rather than achieving anything that could be conceived to be “dominance,” China could decline into substantial economic stagnation. Indeed, some analysts worry that it might lash out militarily in the next few years before that condition fully takes hold.60Michael Beckley and Hal Brands, “The End of China’s Rise,” Foreign Affairs, October 1, 2021, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2021-10-01/end-chinas-rise; Hal Brands and Michael Beckley, Danger Zone: The Coming Conflict with China (New York: Norton, 2002). See also Dmitri Alperovitch with Garrett M. Graff, World on the Brink: How America Can Beat China in the Race for the Twenty-First Century (New York: PublicAffairs, 2024), 19–20, 354. Lashing out seems increasingly unlikely, however, because, to apply Kennan’s dictum about the Soviet Union to the China case, there is a “strong” possibility that Chinese power “bears within it the seeds of its own decay, and that the sprouting of these seeds is well advanced.”

Xi Jinping has been adept at working his way into unchallenged one-man rule in China and at embedding himself at the center of a compliant echo chamber. Central to his rise has been his once-popular campaign to root out corruption. As it happens, pretty much everyone in the Chinese administration is, or has been, corrupt.61Cai Xia, “The Weakness of Xi Jinping,” Foreign Affairs, September/October 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/xi-jinping-china-weakness-hubris-paranoia-threaten-future. This gave Xi the opportunity to weaponize his anti-corruption campaign to remove real or prospective opponents. However, Xi gave a speech in early 2024 in which he declared corruption to still be the greatest threat, and a rising one, to the Chinese Communist Party.62“Xi Jinping urges party to ‘turn knife inward’ to tackle corruption,” Guardian, December 16, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/dec/16/xi-jinping-communist-party-corruption-crackdown. This could be taken, of course, to suggest that his vigorous efforts to counter corruption over the last dozen years have failed. But he forays on, most notably of late by cashiering some of China’s top military leaders.

Collapse may not be in the cards, but Xi is preoccupied with a growing set of domestic problems, most of them deriving from his determination to privilege control by the antiquated and kleptocratic Communist Party over economic development.63As one analyst has recently put, “Chinese President Xi Jinping does not seem to have new ideas, returning to old worries about Western infiltration, corruption, and austerity. His answer to every problem is the same: more power centralized in the Chinese Communist Party.” James Palmer, “China’s Year in Review,” Foreign Policy, December 24, 2024, https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/12/24/china-year-review-2024-economy-price-wars-evs-military-purges-diplomacy/. Among the problems beyond endemic corruption (including in the military) are massive environmental degradation, slowing economic growth, capricious and often incoherent shifts in government policies, recovering from a costly and abruptly canceled “zero COVID” policy, favoring inefficient enterprises, fraudulent statistical reporting, a rapidly aging population (accompanied by a strong and fearful aversion to immigration), enormous overproduction, huge youth unemployment, increasing debt, a housing bubble, restive minorities, protectionist policies, hostility to the private sector, alienation of Western investors, and a clamp-down on civil liberties (one can be imprisoned for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble”) that includes massive policing of the internet.64John Mueller, China: Rise or Demise? 9–19. Adam S. Posen, “The End of China’s Economic Miracle,” Foreign Affairs, September/October 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/end-china-economic-miracle-beijing-washington. Hal Brands and Michael Beckley, Danger Zone: The Coming Conflict with China (New York: Norton, 2002). Scott Lincicome, “Washington Has Lost the (Updated) Script on China,” Cato Institute, December 13, 2023, cato.org/commentary/washington-has-lost-updated-script-china. Zongyuan Zoe Liu, “China’s Real Economic Crisis,” Foreign Affairs, September/October 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/chinas-real-economic-crisis-zongyuan-liu. Carl Minzner, “Xi Jinping Can’t Handle an Aging China,” Foreign Affairs, May 2, 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/xi-jinping-cant-handle-aging-china. Dmitri Alperovitch with Garrett M. Graff, World on the Brink: How America Can Beat China in the Race for the Twenty-First Century (New York: PublicAffairs, 2024), 157–63. Nicholas Eberstadt, “East Asia’s Coming Population Collapse,” Foreign Affairs, May 8, 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/east-asias-coming-population-collapse. Jude Blanchette and Ryan Hass, “Know Your Rival, Know Yourself,” Foreign Affairs, January/February 2025, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/know-your-rival-know-yourself-china.

Business start-ups in China have declined by some 98 percent from 51,302 in 2018 to 1,202 in 2023 and were on track to fall even further in 2024.65Eleanor Olcott and Wang Xueqiao, “How China has ‘throttled’ its private sector,” Financial Times, September 12, 2024, https://www.ft.com/content/1e9e7544-974c-4662-a901-d30c4ab56eb7. In the last few years, there has also been a very considerable decrease in consumer confidence.66The patterns in the graphic are quite interesting. There was some decline in consumer confidence in early 2020 as COVID emerged, but this was reversed by the end of the year as the government took apparent charge. However, a sharp drop was recorded in 2022 in frustration with the increasingly draconian measures designed to contain COVID (particularly in Shanghai). After the government responded in late 2022 by abruptly canceling the containment measures, confidence began something of a comeback until the spring of 2023 when it retreated again to low levels. This might also suggest a decline of confidence in, and in the credibility of, Communist Party dictates, a change in trust that could have unpleasant long-term consequences for the regime.67Adam S. Posen, “The End of China’s Economic Miracle,” Foreign Affairs, September/October 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/end-china-economic-miracle-beijing-washington. See also Barry Naughton lecture at SOAS University of London, “Leverage to Steer the Chinese economy: Xi Jinping as System Builder,” YouTube, July 20, 2023, www.youtube.com/watch?v=GXLRWYCzolE. Zongyuan Zoe Liu, “China’s Real Economic Crisis,” Foreign Affairs, September/October 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/chinas-real-economic-crisis-zongyuan-liu.

Chinese consumer confidence index

A policy of military “containment,” therefore, is scarcely called for. Indeed, it is likely to fuel, not allay, the common motivating belief in China that the Americans are primarily out to stop its growth. Moreover, as Freeman puts it, “There is no military answer to a grand strategy built on a non-violent expansion of commerce and navigation.”68Chas W. Freeman Jr., “The United States and China: Game of Superpowers,” remarks to the National War College Student Body, Middle East Policy Council, February 8, 2018, mepc.org/speeches/united-states-and-china-gamesuperpowers. As Andrew Byers and Randall Schweller have recently argued, “China’s internal weaknesses will eventually be its downfall; we don’t need to engage in Cold War-esque confrontations with China or a severe trade war that will harm American prosperity and risk military conflict with it over Taiwan.”69Andrew Byers and Randall L Schweller, “A Cold Peace with China,” American Conservative, September/October 2024, 24.

The alternative is to wait (perhaps for a rather long time) for China to mellow—although currently in eclipse, there is a substantial liberal element in China.70Michael Pillsbury, The Hundred Year Marathon: China’s Secret Strategy to Replace America as the Global Superpower (New York: Holt, 2015), 15. Zhao Ziyang, Prisoner of the State: The Secret Journal of Premier Zhao Ziyang (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2009). Cai Xia, “The Weakness of Xi Jinping,” Foreign Affairs, September/October 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/xi-jinping-china-weakness-hubris-paranoia-threaten-future. See also Max Boot, “Reagan Didn’t Win the Cold War.” This cautious approach could be pursued while warily profiting from China’s economic size and problems to the degree possible71Adam S. Posen, “The End of China’s Economic Miracle,” Foreign Affairs, September/October 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/end-china-economic-miracle-beijing-washington. and while expanding mutually beneficial exchange.72Jessica Chen Weiss, “The Case Against the China Consensus,” Foreign Affairs, September 16, 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/case-against-china-consensus. The U.S. could also help Taiwan prepare to defend itself while maintaining the decades-long comic opera charade in which Taiwan is independent as long as it doesn’t say so—a position that continues to enjoy majority support in Taiwan.73“Taiwan Independence vs. Unification with the Mainland (1994/12~2024/06),” Election Study Center, National Chengchi University, July 8, 2024, esc.nccu.edu.tw/PageDoc/Detail?fid=7801&id=6963. See also LastWeekTonight, “Taiwan: Last Week Tonight with John Oliver,” YouTube, October 25, 2021, www.youtube.com/watch?v=9Y18-07g39g. That policy could also seek to humor China by welcoming it into the “leadership” club as if that had some tangible meaning, perhaps while issuing periodic if unproductive complaints about civil liberties in China.

In a book published in 2013 as Xi was beginning his rise, China watchers Orville Schell and John Delury concluded that if China’s leaders used their country’s gathering wealth and power to become “more assertive, even aggressive,” they would likely find that “the kind of soft power they so eagerly sought would remain elusive” and that “the kind of global respect” they yearned for “would likely evanesce before their eyes.” However, “should China’s leaders succeed in resisting such a siren song, and instead seek accommodation in disputes with its neighbors, as well as evolving a domestic political system based increasingly on the rule of law, transparency, and accountability of rulers to the ruled,” China “stands a good chance of finally winning the long-dreamed-of title of a truly modern and great country, not just a great power.”74Orville Schell and John Delury, Wealth and Power: China’s Long March to the Twenty-First Century (New York: Random House, 2013), 406. See also Susan L. Shirk, Overreach: How China Derailed Its Peaceful Rise (New York: Oxford University Press, 2022). To Schell’s dismay, China’s leadership has, for the most part, taken the former course and listened to the “siren song.” But in time that could change.

Assessing the political appeal of China-bashing

If the perceived threat from China is primarily economic, and if China’s economy is going into something of a decline, it follows that the political value of China-bashing is also likely to decline. In dealing with China policy today, then, it might be useful to take as a parallel not only the Cold War rivalry with the USSR but the one that smoked throughout the 1980s and early 1990s when Japan was rising as a leading economic power.75On this phenomenon in more detail, see John Mueller, “Remember when Japan was going to take over the world?” Responsible Statecraft, December 30, 2023, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/us-china-relations-2666818984/.

As with China today, concerns about Japanese economic growth and business practices were intense and widespread. For example, Harvard’s Samuel Huntington assured us in phrases that sound much like what we are hearing about China today, a need had suddenly arisen to fear not “missile vulnerability” but “semiconductor vulnerability” and “economics is the continuation of war by other means.”76Samuel P, Huntington, “Why International Primacy Matters,” International Security 17 (4) Spring 1993, 77, 80. Huntington also espied danger in the fact that Japan had become the largest provider of foreign aid and had endowed professorships at Harvard and MIT. “America’s Changing Strategic Interests,” Survival, January/February 1991, 8, 10. Some analysts even saw a military edge.77George Friedman and Meredith LeBard, The Coming War with Japan (New York: St. Martin’s, 1991); Christopher Layne, “The Unipolar Illusion: Why New Great Powers Will Rise,” International Security 17 (4) Spring 1993, 37. Fareed Zakaria, managing editor of Foreign Affairs at the time, recalls “sorting through manuscript after manuscript arguing that Japan was going to take over the world.” Fareed Zakaria, “China is weaker than we thought. Will we change our policies accordingly?” Washington Post, October 20, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2022/10/20/china-weaker-west-policies-must-adapt/. The public responded to these warnings and politicians were predictably quick to get onboard, finding that Japan-bashing sold well. Something of a low point was reached when several members of Congress publicly sledgehammered Toshiba products on the front steps of the Capitol.78Andrew C. McKevitt, Consuming Japan: Popular Culture and the Globalizing of 1980s (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2017).

Per capita GDP of major economies

Despite having stagnated during the 1990s, Japan’s economy still has a much higher per capita GDP than China’s.

These concerns evaporated in the early 1990s when Japan’s “threatening” economy stagnated on its own—as with the end of the Cold War, not thanks to anything the United States did—and as the American economy surged.

This rather benign ending may have something to say about what will happen as China slides into what many suggest will be a lengthy period of slow growth or even stagnation. In fact, the political appeal of China-bashing already seems to be in a degree of remission. China played little role in the presidential campaign of 2024.

When the Japanese firm Toyota became the number one carmaker in the U.S. in recent years, scarcely anyone noticed and fewer cared. One day, it may be that China becomes the number one electric carmaker in the U.S. If the Japan analogy holds, the reaction will be much the same.79These results suggest that the basic momentum may be more nearly bottom-up than top-down. That is, the public may be manipulating the would-be manipulators more than the other way around, and, after the public has clearly embraced a fear, leaders, elites, and the media will often find more purchase in servicing the fear than in seeking to allay it. In his heyday, Donald Trump was an agile Japan-basher, and when he began his quest for the presidency in 2016, he tried it again. Jonathan Soble and Keith Bradsher, “Donald Trump Laces Into Japan With a Trade Tirade From the ’80s,” New York Times, March 7, 2016, www.nytimes.com/2016/03/08/business/international/unease-after-trump-depicts-tokyo-as-an-economic-rival.html. However, by that time Japan-bashing no longer sold while China-bashing did. So inspired, Trump spent the rest of the 2016 campaign building on that theme and repeated much of it in his 2020 campaign as did many other candidates. Ryan Hass, Stronger: Adapting America’s China Strategy in an Age of Competitive Interdependence (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2021), 14. On this phenomenon more generally, see John Mueller, Public Opinion on War and Terror: Manipulated or Manipulating? White Paper, Cato Institute, August 10, 2021, www.cato.org/white-paper/public-opinion-war-terror.

Conclusion

There is a more general lesson that arises from these considerations: although the option of doing nothing or next to nothing in response to a perceived threat might not always be wise, it is one that should at least be on the table for consideration in any rational decision-making process.80Sometimes overreaction has been avoided. India did not overreact when 10 gunmen sent from Pakistan shot up Mumbai in 2008, killing 175 people. Nor did the U.S. overreact when terrorists blew up an airliner filled with Americans over Lockerbie, Scotland, in 1988. It may be relevant to note that, although both attacks generated tremendous publicity for the perpetrators and for their cause, neither was attempted again.

Thus, as discussed earlier, the costly policies of containment and deterrence applied for decades against the Soviet Union were scarcely necessary because they did not substantially impede Soviet ideological expansion and because the Soviets never really saw direct aggression against the West as sensible or productive. At their worst, the policies led to, and justified, participation by the United States in such debacles as the Vietnam War.

In the end, the Cold War was resolved not by crafty U.S. policies and actions, but by the self-destruction of the Soviet Union and of international communism. The United States was strongly inclined to massively inflate the threat it imagined its communist adversary to present, particularly militarily. The current “new cold war” with China is thus in an important respect quite a bit like the old one: an expensive, substantially militarized, and often hysterical campaign to deal with threats that do not exist and may in the long term even lead to self-decline.81John Mueller, China: Rise or Demise? 24.

Something roughly similar happened with a rising Japan, a threat once fashionably and passionately embraced in the United States. Both experiences suggest that, for China policy today, it is both wise and possible to follow a version of Napoleon’s dictum: never interrupt an adversary when it is making a mistake.

Endnotes

- 1Chas W. Freeman Jr., “The United States and China: Game of Superpowers,” Middle East Policy Council, February 8, 2018, mepc.org/speeches/united-states-and-china-gamesuperpowers. Daniel W. Drezner, “This Time is Different: Why U.S. Foreign Policy Will Never Recover,” Foreign Affairs, May/June 2019, 11. Scott D. Sagan, “The Korean Missile Crisis,” Foreign Affairs, November/December 2017, 82.

- 2Hal Brands, “Containment Can Work Against China, Too,” Wall Street Journal, December 3, 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/containment-can-work-against-china-too-11638547169.

- 3Aaron L. Friedberg, Getting China Wrong (Medford, MA: Polity Press, 2022), 195.

- 4Michael Mandelbaum, “The New Containment: Handling Russia, China, and Iran,” Foreign Affairs, March/April 2019, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2019-02-12/new-containment.

- 5George F. Kennan, “The Sources of Soviet Conduct,” Foreign Affairs, July 1947, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/russian-federation/george-kennan-sources-soviet-conduct, 566–82.

- 6Lindsey A, O’Rourke, Covert Regime Change: America’s Secret Cold War (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018). Philip H. Gordon, Losing the Game: The False Promise of Regime Change in the Middle East (New York: St. Martin’s, 2020).

- 7Bernard Brodie, War and Politics (New York: Macmillan, 1973), 63–64.

- 8William Stueck, Rethinking the Korean War: A New Diplomatic and Strategic History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002), 70–75. Nikita Khrushchev, Khrushchev Remembers, ed. Edward Crankshaw and Strobe Talbott (Boston: Little, Brown, 1970), 367–68.

- 9Historicus [George Allen Morgan], “Stalin on Revolution,” Foreign Affairs, January 1949, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russian-federation/1949-01-01/stalin-revolution, 198.

- 10For an extended discussion of this point, see John Mueller, The Stupidity of War (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2021), chs. 1 and 2, and especially 34–41.

- 11George F. Kennan, The Cloud of Danger: Current Realities of American Foreign Policy (Boston: Little, Brown, 1977), 200; “Containment Then and Now,” Foreign Affairs, Spring 1987, 888–87. In contrast, Matt Pottinger holds that “what kept the Cold War cold in the last century” was “unmistakable strength in the form of military hard power.” “‘The Stormy Seas of a Major Test’,” in Matt Pottinger ed., Boiling Moat: Urgent Steps to Defend Taiwan (Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 2024), 18.

- 12Vojtech Mastny, “Introduction” and “Imagining War in Europe” in Vojtech Mastny, Sven G. Holtsmark, and Andreas Wenger, eds., War Plans and Alliances in the Cold War: Threat Perceptions in the East and West (London and New York: Routledge, 2006), 3, 27.

- 13John Mueller, The Stupidity of War (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 35–38; on Eisenhower, 39–40.

- 14John Mueller, “Reassessment of American Policy, 1965–1968,” in Harrison E. Salisbury (ed.), Vietnam Reconsidered: Lessons from a War (New York: Harper & Row, 1984), 48–52.

- 15John Mueller, Overblown: How Politicians and the Terrorism Industry Inflate National Security Threats, and Why We Believe Them (New York: Free Press, 2006), 100. John Mueller, Retreat from Doomsday: The Obsolescence of Major War (New York: Basic Books, 1989), ch. 8.

- 16George W. Breslauer, “Ideology and Learning in Soviet Third World Policy,” World Politics 39 (3) April 1987, 436–37. Robert Jervis, “Was the Cold War a Security Dilemma?” Journal of Cold War Studies 3 (1) Winter 2001, 50.

- 17William C. Wohlforth, ed., Witnesses to the End of the Cold War (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), 91.

- 18John Mueller, “What Was the Cold War About? Evidence from Its Ending,” Political Science Quarterly 119 (4) Winter 2004–05, 609-31. John Mueller, War and Ideas (New York: Routledge, 2011), ch. 5.

- 19On this remarkable development, see John Mueller, Capitalism, Democracy, and Ralph’s Pretty Good Grocery (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999), 103–04, 219–22.

- 20Michael R. Beschloss and Strobe Talbott, At the Highest Levels: The Inside Story of the End of the Cold War (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1993), 417–18.

- 21Andrew Wilson, Ukrainians: Unexpected Nation (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009), 165–69. Mark Kramer, “The Dissolution of the Soviet Union,” Journal of Cold War Studies 24 (1) Winter 2022, 201–04.

- 22Myron Rush, “Fortune and Fate,” National Interest, Spring 1993, 19–25. Mark Kramer, “The Dissolution of the Soviet Union,” Journal of Cold War Studies 24 (1) Winter 2022, 207–11. Max Boot, “Reagan Didn’t Win the Cold War: How a Myth About the Collapse of the Soviet Union Leads Republicans Astray on China,” Foreign Affairs, September 6, 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/reagan-didnt-win-cold-war.

- 23Strobe Talbott, “Remaking the Red Menace,” Time, January 1, 1990, https://time.com/archive/6713848/rethinking-the-red-menace/. Odd Arne Westad, “The Sources of Chinese Conduct: Are Washington and Beijing Fighting a New Cold War?” Foreign Affairs, September/October 2019, 86. See also Boot, “Reagan Didn’t Win the Cold War.”

- 24Kishore Mahbubani, Has China Won? The Chinese Challenge to American Primacy (New York: PublicAffairs, 2020). For the argument that much of the conflict in the South China Sea is over fish, see John Mueller, “China: Rise or Demise?” Policy Analysis no. 917, Cato Institute, May 18, 2021, https://www.cato.org/policy-analysis/china-rise-or-demise, 8.

- 25For data, see Mueller, “China: Rise or Demise?” 3.

- 26Orville Schell and John Delury, Wealth and Power: China’s Long March to the Twentieth Century (New York: Random House, 2013), 403.

- 27John J. Mearsheimer, “America Unhinged,” National Interest, January/February 2014, 12, 26, 30.

- 28John J. Mearsheimer, The Great Delusion: Liberal Dreams and International Realities (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018), 228.

- 29On this issue, see Charles Kenny, The Upside of Down: Why the Rise of the Rest is Good for the West (New York: Basic Books, 2013).

- 30Stephen G. Brooks and William G. Wohlforth, World Out of Balance: International Relations and the Challenge of American Primacy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008). Michael Beckley, Unrivaled: Why America Will Remain the World’s Sole Superpower (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018).

- 31John J. Mearsheimer and Stephen M. Walt, “The Case for Offshore Balancing: A Superior U.S. Grand Strategy,” Foreign Affairs, July/August 2016, 70–83.

- 32See also Simon F. Reich and Richard Ned Lebow, Good-Bye Hegemony! Power and Influence in the Global System (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014).

- 33Sean Mirski, We May Dominate the World: Ambition, Anxiety, and the Rise of the American Colossus (New York: PublicAffairs, 2023). For a more extended discussion of this book, see John Mueller, “The Perils of the Hegemon,” Cato at Liberty blog, Cato Institute, November 10, 2023, www.cato.org/blog/perils-hegemon.

- 34For example, in 1915, a mission was sent to Haiti after what Mirski calls its “tinpot dictator” was killed by an angry mob. This led to a costly and chaotic occupation that lasted until 1934, after which the country devolved back to what seems more or less like what had existed before. An earlier enterprise in 1903 was more successful. In the 60 years prior, revolutionists in the province of Panama had sought at least 50 times to secede from Colombia, and the United States had often helped Colombia put those rebellions down. By 1903, however, the U.S. had become anxious to get a canal built there after a French effort had gone bankrupt, and was frustrated with negotiations with Colombia. Accordingly, the United States switched sides. An amazingly inept expeditionary force sent by Colombia to counter the secessionist effort was readily bribed into submission. In the end, however, Mirski deems the American caper to have been unnecessary and a “blunder.” Mirski, We May Dominate the World, 156.

- 35Mirski, We May Dominate the World, 2, 285, 290.

- 36Actually many Spaniards welcomed the war because a defeat would have allowed them to withdraw honorably from their highly troublesome colony. Melvin Small, Was War Necessary? National Security and U.S. Entry into War (Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE Publications, 1980). Robert Jervis, Richard Ned Lebow, and Janice Gross Stein, Psychology and Deterrence (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985).

- 37Mirski, We May Dominate the World, 174¬–175.

- 38Mirski, We May Dominate the World, 12. Actually it seems likely that the European rivals never got around to reinserting themselves not so much because of American “hegemony” but because they were fully consumed with other tasks: colonizing Africa and Asia, and misdealing with each other in a manner that led to two massive wars on their continent.

- 39As the Cato Institute’s Doug Bandow notes, “the world’s greatest power has proven incapable even of replacing the hostile government of a small island almost within sight of its coast.” Doug Bandow, “Blame America Too for Our Ruptured Relations with the Chinese,” American Conservative, July 4, 2019, emphasis in the original.

- 40On the futility of economic sanctions to change policy, see Richard Hanania, “Ineffective, Immoral, Politically Convenient: America’s Overreliance on Economic Sanctions and What to Do About It,” Policy Analysis no. 884, Cato Institute, February 18, 2020, https://www.cato.org/policy-analysis/ineffective-immoral-politically-convenient-americas-overreliance-economic-sanctions; Murat Sofuoglu and Melis Alemdar, “Have US-Imposed Sanctions Ever Worked?” interview with Gary Hufbauer, trtworld.com, September 24, 2018, https://www.trtworld.com/magazine/have-us-imposed-sanctions-ever-worked-20428.

- 41The chief hegemonic success story of late (besides, perhaps, keeping Soviet weapons that are potentially offensive out of Cuba), was the use of military force that successfully reimposed democracy when it lapsed in tiny Panama in 1989 and even tinier Grenada in 1983. Military interventions had routinely failed earlier in the century. This time, however, they worked: democracy resumed after the Americans left.

- 42Mirski, We May Dominate the World, 347.

- 43See also Stephen M. Walt, “Stop Worrying About Chinese Hegemony in Asia,” Foreign Policy, May 31, 2023, https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/05/31/stop-worrying-about-chinese-hegemony-in-asia/; Michael Schuman, Superpower Interrupted: The Chinese History of the World (New York: PublicAffairs, 2020), 316–17.

- 44Jane Harman et al, “Commission on the National Defense Strategy,” July 2024, https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/nds_commission_final_report.pdf, 5.

- 45For that estimate, see M. Taylor Fravel, George J. Gilboy, and Eric Heginbotham, “Estimating China’s Defense Spending: How to Get It Wrong (and Right),” Texas National Security Review 7 (3) Summer 2024.

- 46Nathan Beauchamp-Mustafaga and Howard Wan, “The Threat From Overseas Chinese Military Bases Is Overblown,” Diplomat, July 30, 3024, https://thediplomat.com/2024/07/the-threat-from-overseas-chinese-military-bases-is-overblown/; Mike Sweeney, “Challenges to China’s Blue Water Operations,” Defense Priorities, April 30, 2024, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/challenges-to-chinese-blue-water-operations/.

- 47Hal Brands and Michael Beckley, Danger Zone: The Coming Conflict with China (New York: Norton, 2002), 12, 68–73, 125–26.

- 48Fareed Zakaria, “In 2024, U.S. domestic politics will cast a dark shadow across the world,” Washington Post, December 15, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2023/12/15/us-dysfunction-chaos-china-russia-hamas/. Shaoyu Yuan, “Goodbye, Wolf Warrior: Charting China’s transition to a more accommodating diplomacy,” International Affairs 100 (5) 2024, 2217–32.

- 49James Kynge and Jonathan Wheatley, “China pulls back from the world: rethinking Xi’s ‘project of the century’,” Financial Times, December 11, 2020, https://www.ft.com/content/d9bd8059-d05c-4e6f-968b-1672241ec1f6. Michael Bennon and Francis Fukuyama, “China’s Road to Ruin: The Real Toll of Beijing’s Belt and Road,” Foreign Affairs, September/October 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/belt-road-initiative-xi-imf. See also Dmitri Alperovitch with Garrett M. Graff, World on the Brink: How America Can Beat China in the Race for the Twenty-First Century (New York: PublicAffairs, 2024), 163–67.

- 50Condoleezza Rice, “The Perils of Isolationism: The World Still Needs America—and America Still Needs the World,” Foreign Affairs, September/October 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/perils-isolationism-condoleezza-rice.

- 51Harman et al, “Commission on the National Defense Strategy,” 5, 7.

- 52Hal Brands and Michael Beckley, Danger Zone: The Coming Conflict with China (New York: Norton, 2002), 125, 129.

- 53For skeptical commentary on this issue, see Nick Sweeney, “How Militarily Useful Would Taiwan be to China?” Defense Priorities, April 12, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/how-militarily-useful-would-taiwan-be-to-china/. It might also be pointed out that, in the contingency considered by some analysts to be “most likely,” the military conquest of Taiwan would require China to outdo Pearl Harbor by raining thousands of missiles not only on Taiwan but American military bases and ships in Japan and Guam. Hal Brands and Michael Beckley, Danger Zone: The Coming Conflict with China (New York: Norton, 2002), 135. This would scarcely ease China’s problems in expanding beyond Taiwan.

- 54Noah Robertson, “How DC became obsessed with a potential 2027 Chinese invasion of Taiwan,” Defense News, May 7, 2024, https://www.defensenews.com/pentagon/2024/05/07/how-dc-became-obsessed-with-a-potential-2027-chinese-invasion-of-taiwan/.

- 55Timothy R. Heath, “Is China Planning to Attack Taiwan? A Careful Consideration of Available Evidence Says No,” War on the Rocks, December 14, 2022, https://warontherocks.com/2022/12/is-china-planning-to-attack-taiwan-a-careful-consideration-of-available-evidence-says-no/. See also Timothy R. Heath, “Is China Prepared for War?” testimony presented to the U.S.-China Economic and Security Committee, June 13, 2024, www.rand.org/pubs/testimonies/CTA3381-1.html; Jessica Chen Weiss, “Don’t Panic About Taiwan: Alarm Over a Chinese Invasion Could Become a Self-Fulfilling Prophecy,” Foreign Affairs, March 21, 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/taiwan-chinese-invasion-dont-panic.

- 56Noah Robertson, “How DC became obsessed…”

- 57William Spaniel, “What Everyone Gets Wrong about China Invading Taiwan,” YouTube, August 3, 2024, www.youtube.com/watch?v=8eO4zQew4CA. Mueller, “China: Rise or Demise?” 9. Matt Pottinger, “‘The Stormy Seas of a Major Test’,” in Matt Pottinger (ed.), Boiling Moat: Urgent Steps to Defend Taiwan (Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 2024), 10–11. David Sacks, “Why China Would Struggle to Invade Taiwan,” Council on Foreign Relations, New York, June 12, 2024, www.cfr.org/article/why-china-would-struggle-invade-taiwan. Lonnie Henley, “Many Ways to Fail: The Costs to China of an Unsuccessful Invasion,” U.S. Institute of Peace, November 5, 2024, www.usip.org/publications/2024/11/many-ways-fail-costs-china-unsuccessful-taiwan-invasion.

- 58Face the Nation, “CIA Director William Burns on “Face the Nation with Margaret Brennan” | full interview,” YouTube, February 16, 2023, at 17 minutes, www.youtube.com/watch?v=HN4bgqKq2MU. On Putin’s folly in Ukraine, see John Mueller “The Upside of Putin’s Delusions,” Foreign Affairs, August 2, 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/russian-federation/upside-putins-delusions; Rajan Menon, “Putin Has Already Lost,” New York Times, February 22, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/02/22/opinion/russia-ukraine-invasion-putin.html; Rajan Menon, “Putin’s Victory Will Be a Hollow One,” Foreign Policy, January 13, 2025, https://foreignpolicy.com/2025/01/13/russia-ukraine-war-putin-military-strategy-victory-settlement-territory/.

- 59Asia Society, “China and Taiwan: Will it Come to Conflict?” YouTube, July 1, 2024, at 39 minutes, www.youtube.com/watch?v=v5CH4mFGNXk.

- 60Michael Beckley and Hal Brands, “The End of China’s Rise,” Foreign Affairs, October 1, 2021, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2021-10-01/end-chinas-rise; Hal Brands and Michael Beckley, Danger Zone: The Coming Conflict with China (New York: Norton, 2002). See also Dmitri Alperovitch with Garrett M. Graff, World on the Brink: How America Can Beat China in the Race for the Twenty-First Century (New York: PublicAffairs, 2024), 19–20, 354.

- 61Cai Xia, “The Weakness of Xi Jinping,” Foreign Affairs, September/October 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/xi-jinping-china-weakness-hubris-paranoia-threaten-future.

- 62“Xi Jinping urges party to ‘turn knife inward’ to tackle corruption,” Guardian, December 16, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/dec/16/xi-jinping-communist-party-corruption-crackdown.

- 63As one analyst has recently put, “Chinese President Xi Jinping does not seem to have new ideas, returning to old worries about Western infiltration, corruption, and austerity. His answer to every problem is the same: more power centralized in the Chinese Communist Party.” James Palmer, “China’s Year in Review,” Foreign Policy, December 24, 2024, https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/12/24/china-year-review-2024-economy-price-wars-evs-military-purges-diplomacy/.

- 64John Mueller, China: Rise or Demise? 9–19. Adam S. Posen, “The End of China’s Economic Miracle,” Foreign Affairs, September/October 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/end-china-economic-miracle-beijing-washington. Hal Brands and Michael Beckley, Danger Zone: The Coming Conflict with China (New York: Norton, 2002). Scott Lincicome, “Washington Has Lost the (Updated) Script on China,” Cato Institute, December 13, 2023, cato.org/commentary/washington-has-lost-updated-script-china. Zongyuan Zoe Liu, “China’s Real Economic Crisis,” Foreign Affairs, September/October 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/chinas-real-economic-crisis-zongyuan-liu. Carl Minzner, “Xi Jinping Can’t Handle an Aging China,” Foreign Affairs, May 2, 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/xi-jinping-cant-handle-aging-china. Dmitri Alperovitch with Garrett M. Graff, World on the Brink: How America Can Beat China in the Race for the Twenty-First Century (New York: PublicAffairs, 2024), 157–63. Nicholas Eberstadt, “East Asia’s Coming Population Collapse,” Foreign Affairs, May 8, 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/east-asias-coming-population-collapse. Jude Blanchette and Ryan Hass, “Know Your Rival, Know Yourself,” Foreign Affairs, January/February 2025, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/know-your-rival-know-yourself-china.

- 65Eleanor Olcott and Wang Xueqiao, “How China has ‘throttled’ its private sector,” Financial Times, September 12, 2024, https://www.ft.com/content/1e9e7544-974c-4662-a901-d30c4ab56eb7.