January 23, 2026

Move on from Washington’s outdated Cuba policy

Key points

- U.S. policy on Cuba remains defined by a Cold War-era paradigm centered on a six-decade-old economic embargo that’s still in effect despite its failure to pressure Cuba into enacting political reforms.

- Cuba’s strengthening of relations with China and Russia, along with its crackdowns on dissent, has spurred the Trump administration to increase pressure on the island. This pressure campaign has failed to produce political change in Cuba while encouraging its closer relations with China and Russia the U.S. seeks to prevent.

- U.S nuclear deterrence and vast U.S. power advantages meant Cuba presented no real threat to the United States during the Cold War, even as it cooperated with the Soviet Union. Cuba poses even less of a threat today, and U.S. policy should reflect this reality.

- A détente with Cuba could hold numerous economic, diplomatic, and security benefits for the United States. Even if Congress will not lift the embargo, the U.S. can take steps that would make normalization more likely while giving up nothing in return.

The Western Hemisphere is often an afterthought in discussions about U.S. grand strategy, but this is changing. The Trump administration continues to elevate the importance of Latin America and the Caribbean in U.S. foreign policy. President Trump has deployed approximately 10 percent of the U.S. Navy fleet there since September, is conducting strikes against boats allegedly carrying drugs to the United States, and is pressuring states in the region, especially Venezuela, to cater to U.S. policy demands. The 2025 National Security Strategy elevates the Western Hemisphere to a top U.S. priority.1“National Security Strategy of the United States,” White House, November 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/2025-National-Security-Strategy.pdf. And in early 2026, U.S. forces raided Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro’s compound in Caracas, captured him, and flew him back to New York to stand trial on drug trafficking charges.

However, not everything has changed. If there was ever a U.S. policy in Latin America that could be described as archaic, it’s Washington’s approach to Cuba. The island nation, located 90 miles off of Florida’s southern coast, remains a boogeyman for key constituencies, notwithstanding the massive power disparity in Washington’s favor. To the extent Cuba poses problems for the United States, it is due less to Havana’s ability to threaten U.S. interests than its internal woes—a currency crisis, high inflation, a state-dominated economy, and closed political system—that add to the region’s migration problems. Of course, these are problems that the U.S. embargo exacerbates by design. In the grand scheme, Cuba is a marginal player led by a regime whose only impressive quality is its longevity.

Yet with the exception of a two-year rapprochement during President Barack Obama’s second term and modest policy reforms during Joe Biden’s administration, the United States continues to treat Cuba as a threat. A U.S. policy originally formulated during the early days of the Cold War thus lingers well into the twenty-first century. Influenced by a Cuban-American diaspora that maintains significant political power in Florida, successive U.S. administrations across party lines have leaned on the six-decade-old embargo, financial sanctions, and diplomatic isolation to pressure the Cuban government to reform.2Susan Eckstein, “How Cubans Transformed Florida Politics and Gained National Influence,” in Viviana Díaz Balsera and Rachel A. May, La Florida: Five Hundred Years of Hispanic Presence (Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida, 2014): 263–284.

The Trump administration is no exception. Immediately after assuming office, President Trump rescinded a Biden-era executive order that dropped Cuba from the U.S. State Department’s list of state sponsors of terrorism.3“Initial Rescissions of Harmful Executive Orders and Actions,” White House, January 20, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/initial-rescissions-of-harmful-executive-orders-and-actions/. In June 2025, Trump upped the pressure by sanctioning any third-country entity engaging in transactions with the Grupo de Administracion Empresarial S.A., a Cuban military-run conglomerate estimated to control approximately 60 percent of the Cuban economy.4“National Security Presidential Memorandum/NSPM-5,” White House, June 30, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/06/national-security-presidential-memorandum-nspm-5/. Cuban President Miguel Diaz-Canel was sanctioned by the Trump administration in July for “gross violations of human rights.”5Nora Gámez Torres, “In a first, U.S. sanctions Cuba leader Miguel Díaz Canel for human rights violations,” Miami Herald, July 11, 2025, https://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/cuba/article310412200.html. The United States has suspended working-level discussions with Cuba on migration despite the fact that U.S. immigration authorities encountered around 600,000 Cubans at the U.S. southern border between 2022–2024.6Carmen Sesin and Orlando Matos, “Trump admin says it won’t hold migration talks with Cuba,” NBC News, April 25, 2025, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/trump-admin-wont-hold-migration-talks-cuba-rcna203035. The successful extraction of Maduro from Venezuela, Cuba’s closest regional partner, has also emboldened the Trump administration to take an even tougher position on Cuba, with Secretary of State Marco Rubio saying mere hours after Maduro’s capture, ‘If I lived in Havana and I was in the government, I’d be concerned at least a little bit.’7Ryan Mancini, “Rubio sends warning to Cuba’s leaders after Maduro’s removal: ‘I’d be concerned,’” The Hill, January 3, 2026, [https://thehill.com/homenews/administration/5671259-rubio-warns-cuba-maduro-capture/](https://thehill.com/homenews/administration/5671259-rubio-warns-cuba-maduro-capture/).

The United States justifies these measures largely on human rights grounds, but geopolitics is part of its calculations as well. In recent years, Cuba has extended its outreach to China and Russia, Washington’s two biggest competitors, by increasing diplomatic ties and signing infrastructure deals to compensate for the U.S. embargo. Predictably, at a time when U.S. officials view great power competition with China and Russia as the north star of U.S. foreign policy, the Trump administration treats such Cuban entreaties as a threat to U.S. dominance in its near-abroad.8“Statement of Admiral Alvin Holsey, Commander, United States Southern Command,” Senate Armed Services Committee, February 13, 2025, https://www.southcom.mil/Portals/7/Documents/Posture%20Statements/2025_SOUTHCOM_Posture_Statement_FINAL.pdf?ver=5L0oh0wyNgJ2_qzelc6wKQ%3d%3d, 14. This is not exclusive to Trump’s second term: the first Trump administration also imposed harsher measures on the island, citing Cuba’s “destabilizing role in the Western Hemisphere.”9“Treasury and Commerce Implement Changes to Cuba Sanctions Rules,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, June 4, 2019, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm700.

The reality is less dramatic. Cuba is at best an annoyance to the U.S., and its ability to directly threaten U.S. security interests is highly limited. The United States can afford to be bold in pursuing an alternative policy that has a chance of achieving real political reform on the island. More importantly, treating Cuba as a normal state rather than a Cold War-era anachronism will help alleviate the minor problems it poses for the United States.

This paper presents a case for why ditching six decades of U.S. Cuba policy failure is the best path forward. The first section explores widespread U.S. misconceptions about Cuban power during the Cold War and shows how those errors continue today. The next section explains why breaking from the status quo is not only morally correct but practically advantageous for U.S. foreign policy interests. The third section demonstrates how the current U.S. approach is driving Havana closer to Russia and China. The final section offers recommendations, all of which come at virtually no cost to the United States.

Cuba’s ‘threat’ to the United States

The U.S. approach to Cuba during the Cold War reflected a consensus that Fidel Castro posed a major national security problem. This was certainly the assessment of multiple U.S. presidents who embarked on a policy of economic pressure, diplomatic isolation, and covert operations to undermine Castro’s regime. The United States hoped to distance Cuba from the Soviet Union and weaken the Cuban state’s ability to function.

But Cuba’s threat to the United States during this time was minimal and driven more by U.S. concerns over having a hostile neighbor—however small—in its own neighborhood than an accurate assessment of Cuba’s power. This threat inflation continues today, even though Cuba is weaker.

Cuban behavior during the Cold War

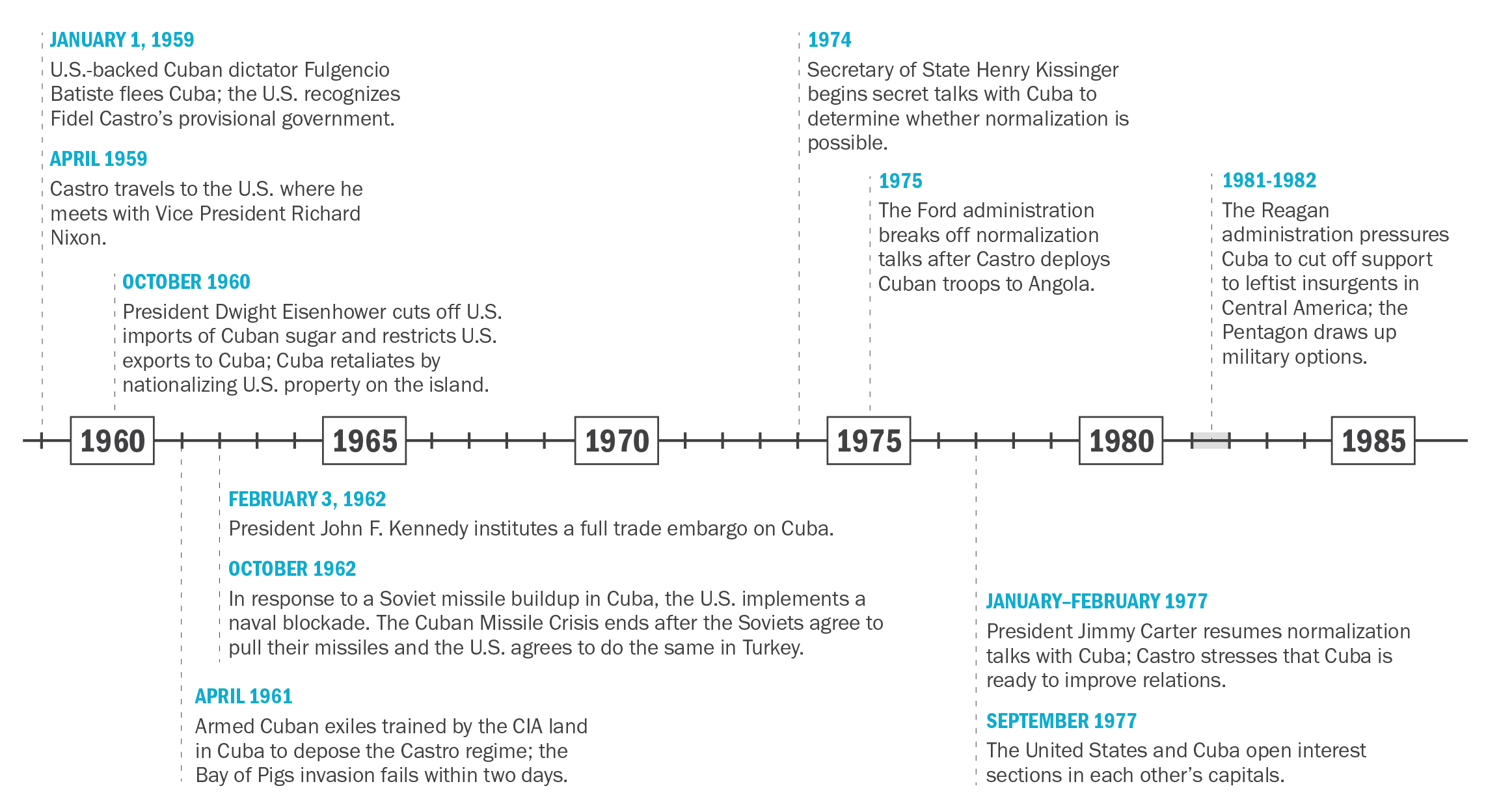

The U.S. perception of Cuba as an enemy state began almost immediately after Fidel Castro’s revolution overturned Fulgencio Batista’s regime in January 1959. At first, the Eisenhower administration was unsure about the young Castro’s ideological leanings, and in the months after the Cuban Revolution, the United States was open to establishing a working relationship with him. On January 7, 1959, seven days after Batista fled the island, the United States officially recognized the new government in Havana. In April 1959, Castro traveled to the United States and met with select U.S. officials, most notably Vice President Richard Nixon.10Alan McPherson, “The Limits of Populist Diplomacy: Fidel Castro’s April 1959 Trip to North America,” Diplomacy & Statecraft 18, no. 1 (2007): 237–268. Nixon’s assessment of Castro was mixed but pragmatic.11“Editorial Note,” Foreign Relations of the United States, 1958–1960, Cuba, Volume VI, State Department Office of the Historian, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1958-60v06/d287.

The relationship soon soured. Castro increasingly viewed the United States as an interloper in Cuban affairs; the United States, in turn, saw Castro as advancing communist influence.12Tad Szulc, “Cuba Exploiting Discord with U.S.; Relations at Low Point and Seem Due to Remain So — Washington Called Foe,” New York Times, December 20, 1959, https://www.nytimes.com/1959/12/20/archives/cuba-exploiting-discord-with-us-relations-at-low-point-and-seem-due.html. Castro’s nationalization of U.S. property on the island, in tandem with his overtures to the Soviet Union and his attempt to break from the U.S. sphere of influence, prompted Eisenhower to squeeze Cuba economically.13In November 1960, a month before Eisenhower instituted a ban on Cuban sugar imports, he wrote a letter to UK Prime Minister Harold Macmillan explaining why those measures were needed to expel Soviet influence from the island. As Eisenhower wrote, “the Castro Government is now fully committed to the Bloc. We cannot prudently follow policies looking to a reform of Castro’s attitude and we must rely, frankly, on creating conditions in which democratically minded and Western-oriented Cubans can assert themselves and regain control of the island’s policies and destinies.” See “Letter From President Eisenhower to Prime Minister Macmillan,” Foreign Relations of the United States, 1958–1960, Cuba, Volume VI, State Department Office of the Historian, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1958-60v06/d551; Michael Grow, U.S. Presidents and Latin American Interventions (Lawrence, Kansas: University of Kansas Press 2008): 41–45. Less than two years later, President John F. Kennedy established an economic embargo, which prohibited all trade with Cuba and subjected offenders to criminal penalties. Kennedy also approved the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion and authorized a series of covert operations to oust Castro—all of which failed.14“Proclamation 3447—Embargo on All Trade with Cuba,” White House, February 3, 1962, accessed at https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/proclamation-3447-embargo-all-trade-with-cuba; “Memorandum for the Special Group from Brigadier General Landsale,” Central Intelligence Agency, August 6, 1962, accessed at https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/operation%20mongoose%20-%20futu%5B15436924%5D.pdf.

U.S.-Cuba relations throughout the Cold War were largely characterized by mutual contempt. Castro’s Cuba was depicted by the U.S. as a troublemaker trying to spread its revolution across Latin America. Presidents Ford and Carter, who engaged in back-channel negotiations with Havana, abandoned the effort after Cuban forces were dispatched to Cold War-era hotspots in Africa. Cuban foreign policy became synonymous with Soviet expansionism in the minds of U.S. officials, and Castro was depicted as doing the Soviet Union’s dirty work in Africa and Latin America.15Duccio Basosi, “‘Something that apparently troubles the Cubans significantly’: Jimmy Carter’s attempt to pressure Cuba ‘out of Africa’ through the Non-Aligned Movement, 1977–78,” Cold War History 24, no. 3 (2004): 359–377. President Ronald Reagan in particular tried to convince the American public that Cuba and the Soviet Union had established an aggressive communist beachhead in the Western Hemisphere.16“Address Before a Joint Session of the Congress on Central America,” Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, April 27, 1983, https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/speech/address-joint-session-congress-central-america.

Despite the sensationalism, U.S. assessments of Cuba during the Cold War were a classic case of leaders exaggerating dangers to justify decisions they have already made.17Benjamin H. Friedman, “The Terrible ‘Ifs’,” Regulation (Winter 2008): 32–40, https://object.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/serials/files/regulation/2007/12/v30n4-1 .pdf. This is not to suggest that U.S. officials at the time were entirely wrong to worry about Cuban foreign policy. But U.S. security, power, and prestige in the Western Hemisphere were more secure than the conventional wisdom allowed.

Cuba never possessed the military capability to directly threaten the United States. Despite the conventional Soviet systems in its arsenal, the Cuban military lacked the ability to bring force to bear across the sea. Even if it did have such a capability, any Cuban attack on the United States would have prompted massive U.S. retaliation, meaning Cuba was deterred from taking such action in the first place.

The only way Cuba was going to pose a threat to the United States was by serving as a staging point for foreign forces or operating as a Soviet proxy to support communist insurgencies elsewhere. Yet the dawn of the “nuclear revolution” meant the idea of Cuba becoming a Soviet base to attack Americans was hard to imagine. Even before the United States deployed thousands of nuclear weapons with intercontinental range, U.S. conventional capabilities assured that any such attack would have been the end of the Castro regime and the Soviet personnel stationed on the island.18Robert Jervis, “The Nuclear Revolution and the Common Defense,” Political Science Quarterly 101, no. 5 (1986): 689–703. The overwhelming destructive power of nuclear weapons, combined with their deployment in numbers no rival could preemptively destroy, made a direct strike on the United States suicidal.19William D’Ambruoso, “The Restraining Effect of Nuclear Deterrence,” Defense Priorities, June 16, 2023, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/the-restraining-effect-of-nuclear-deterrence/#continuity-in-the-new-nuclear-age.

Key Cold War events in U.S.-Cuba relations

This stabilizing effect of mutual terror was tested during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. After a Soviet nuclear missile buildup in Cuba and a U.S.-enforced blockade of the island, President John F. Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev de-escalated by negotiating an accord that traded a U.S. promise not to invade Cuba for a withdrawal of Soviet missiles.20According to the U.S. Department of Energy, the United States possessed more than 25,000 nuclear weapons at the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis. For more, see “Transparency in the U.S. Nuclear Weapons Stockpile,” U.S. Department of Energy, https://www.energy.gov/nnsa/transparency-us-nuclear-weapons-stockpile. Kennedy also secretly agreed to withdraw U.S. intermediate-range ballistic missiles from Turkey in a bid to make the Soviet Union’s own missile withdrawal from Cuba more palpable.21“The Jupiter Missiles and the Endgame of the Cuban Missile Crisis, 60 Years Ago,” National Security Archive, February 16, 2023, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/briefing-book/cuban-missile-crisis-nuclear-vault/2023-02-16/jupiter-missiles-and-endgame-cuban. In the end, the Soviets were not willing to fight a war with the United States on Cuba’s behalf.

U.S. concerns over Cuba had more to do with political considerations like prestige and credibility, not military considerations like the balance of power. While U.S. leaders were unnerved by Soviet missiles in their backyard, they understood that this “did not at all” change the strategic balance at the time, as Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara admitted.22Raymond Garthoff, Reflections on the Cuban Missile Crisis (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 1989): 207. And as declassified documents attest, the Soviets did not see the missiles as useful for attacking the United States so much as deterring it at a time when Moscow was losing the superpower missile race.23Serhii Plotkhy, Nuclear Folly: A History of the Cuban Missile Crisis (New York: W.W Norton & Company, 2021): 52–53, 56. In other words, the gambit was precipitated by Soviet weakness, not strength.

Of course, even after the Cuban Missile Crisis was resolved, U.S. officials remained wary of Cuba‘s relationship with the Soviet Union. This is not surprising: great powers are notoriously paranoid about peer rivals encroaching on their spheres of influence.24Evan N. Resnick, “Interests, ideologies, and great power spheres of influence,” European Journal of International Relations 29, no. 3 (2022): 563–588. Still, a Soviet-aligned Cuba did not really affect the balance of power between the superpowers. The United States held tangible military and economic advantages over the Soviet Union—even in Latin America, Cuban-inspired communism did little to upset U.S. moves against leftish regimes and actually compelled U.S.-supported governments in the region to adopt stronger balancing behavior. As Stephen Van Evera observed, large stretches of Africa and Latin America were strategically insignificant in terms of raw industrial power—taking control of them would not have added to Soviet (or U.S.) wealth or military capability.25Stephen Van Evera, “Why Europe matters, why the third world doesn’t: American grand strategy after the cold war,” Journal of Strategic Studies 13, no. 2 (1990): 1–51. In fact, trying to do so might have proved to be a drag on national power; nationalism would provoke costly resistance to outside rule.26Van Evera, “Why Europe matters,” 17.

Cuba’s interventions in the third world, meanwhile, proved much less destabilizing than U.S. officials had assessed. When Castro decided in 1975–1976 to deploy tens of thousands of Cuban troops into Angola to prop up a Marxist-leaning government, U.S. officials warned of a potential resurgence of Soviet-aligned states in Southern Africa.27“Letter to the Speaker of the House of Representatives on the Situation in Angola,” White House, January 27, 1976, accessed at https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/letter-the-speaker-the-house-representatives-the-situation-angola; “Washington Special Actions Group Meeting,” White House, March 24, 1976, accessed at https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB487/docs/03%20-%20Washington%20Special%20Actions%20Group%20Meeting,%20Cuba,%20March%2024,%201976.pdf. The Reagan administration made similar arguments about Cuban machinations in Central America.28Kissinger was a central player in these arguments as well. See “Report of the National Bipartisan Commission on Central America,” January 10, 1984, accessed at https://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/federal_documents/8/. None of these predictions came to pass. While the Cuban intervention helped save the Marxist government in Angola, the endeavor proved costly and time-consuming, and when Cuba finally withdrew its troops in 1989, no dominoes fell in Africa. With the exception of Nicaragua, Cuban-supported insurgencies in the Western Hemisphere failed to capture a single state.

Finally, for as much as the United States categorized Cuba as a loyal Soviet proxy during the Cold War, the reality was more complicated. While Cuban foreign policy often aligned with Soviet preferences, it was not subservient to them. In 1977, Cuba intervened to support a Marxist government in Ethiopia not because the Soviet Union requested it but because the Cuban government believed Ethiopia’s Marxist system was worth preserving.29Piero Gleijeses, “Moscow’s Proxy? Cuba and Africa 1975–1988,” Journal of Cold War Studies 8, no. 4 (2006): 98–146. Cuba and the Soviet Union clashed on military strategy in Angola and disagreed on policy in El Salvador.30William M. LeoGrande, Our Own Backyard (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000) 88. Toward the end of the Cold War, Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev failed to convince Castro to cut relations with Nicaragua’s Sandinista government, demonstrating Havana’s independent streak.31While Cuba delivered a diplomatic proposal to the Soviets in a bid to advance diplomacy in Central America, Havana’s roadmap was rendered irrelevant after the Sandinistas lost the 1990 presidential election in Nicaragua and handed over power. See, William M. LeoGrande and Peter Kornbluh, Back Channel to Cuba: The Hidden History of Negotiations Between Washington and Havana (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014): 259–261.

Cuba is even weaker today

Allegations of Cuba’s supposed danger persist even as the international environment has changed to Cuba’s disadvantage. The collapse of the Soviet Union, Cuba’s major foreign benefactor, ushered in a period of severe hardship for Havana, culminating in Fidel Castro’s declaration of a “special period” of strict rationing to manage the economic fallout. Cuban economist Carmelo Mesa-Lago estimates that successive Soviet governments provided Cuba with approximately $65 billion in aid between 1960–1990.32Carla Gloria Colomé, “Carmelo Mesa-Lago: ‘Today’s Cuba is a catastrophe,’” El Pais, June 16, 2024, https://english.elpais.com/international/2024-06-16/carmelo-mesa-lago-todays-cuba-is-a-catastrophe.html?outputType=amp; for more, see “Carmelo Mesa-Lago, “The Economic Effects on Cuba of the Downfall of Socialism in the USSR and in Eastern Europe” in Carmelo Mesa-Lago, Cuba After the Cold War (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1993): 133–196. By 1991, all of the aid programs were gone.

Cuba’s situation is arguably even more dire today than during the 1990s. The COVID-19 pandemic, economic mismanagement, and U.S. sanctions have hindered Cuba’s economic growth. Energy blackouts are the new normal and tourism to the island has dried up; there were only 2.2 million visitors to Cuba in 2024, less than half of pre-pandemic levels.33David Sherwood, “Cuba tourism struggles as blackouts and shortages deter visitors,” Reuters, December 19, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/cuba-tourism-struggles-blackouts-shortages-deter-visitors-2024-12-19/. The Cuban economy has contracted by more than 10 percent over the last five years.34Nora Gámez Torres, “Minister ignites uproar saying Cuba has no beggars, only people ‘disguised as beggars,’” Miami Herald, July 16, 2025, https://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/cuba/article310724920.html. Cuba has also lost around 10 percent of its population since the pandemic, with more than 675,000 Cubans migrating to the United States alone.35Frances Robles et al, “10 Years Ago, a U.S. Thaw Fueled Cuban Dreams. Now Hope Is Lost,” New York Times, December 27, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/12/27/world/americas/obama-us-thaw-cuba-crisis.html.

Cuba’s military power has withered as well, a consequence of its declining economic fortunes and the absence of a great power patron that can match the former Soviet Union’s largesse. In 1982, U.S. intelligence agencies described Cuba as “by far the most formidable and largest military force in the Caribbean Basin with the exception of the United States.”36“Cuban Armed Forces and the Soviet Military Presence,” United States Department of State, August 1982, accessed at https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP85M00363R001403210041-0.pdf. This is hardly the case today. Cuba’s military was not immune from the painful austerity measures enacted during the 1990s and saw its budget slashed by 60 percent. The Cuban armed forces’ end-strength declined from 300,000 personnel to 60,000 during this period and regular training was indefinitely postponed.37Hal Klepak, ”Reflections on U.S.-Cuba Military-to-Military Contacts,” Strategic Forums 95 (2016), accessed at https://digitalcommons.ndu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1017&context=strategic-forums. By 1997, the Central Intelligence Agency reported that Cuba’s air force no longer had the capacity to defend Cuban airspace against modern-day jet fighters.38“The Cuban Threat to U.S. National Security,” U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency, November 19, 1997, accessed at https://irp.fas.org/dia/product/980507-dia-cubarpt.htm.

Diplomatically, Cuba has lost influence as well. Although it’s no longer treated by fellow Latin American states as a renegade power, Cuba’s ability to impact regional events is limited. The one major diplomatic initiative the Cubans undertook in recent years, mediating a peace agreement between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), actually aligned with U.S. security interests.

Perspective on Cuba’s relations with China and Russia

So while Cuba’s supposed threat to the United States is largely fictitious, U.S. policy has not caught up to this reality. As great power competition has emerged as a top U.S. foreign policy priority, U.S. officials have become alarmed over Cuba’s attempts to strengthen relations with China as well as China’s attempts to increase its own influence in Latin America.

This is not exclusive to the Trump administration. The 2022 National Security Strategy under President Joe Biden warned about China’s efforts to destabilize the Western Hemisphere.39As the 2022 NSS states, the United States “will support effective democratic governance responsible to citizen needs, defend human rights and combat gender-based balance, tackle corruption, and protect against external interference or coercion, including from the PRC [China], Russia, or Iran.” See “National Security Strategy,” White House, October 2022, https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Biden-Harris-Administrations-National-Security-Strategy-10.2022.pdf, 41. The U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, a congressionally appointed panel analyzing all aspects of Chinese power, wrote in its 2024 annual report that Beijing’s frequent forays into Latin American diplomacy was cause for concern.40“2024 Report to Congress of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission,” U.S. Congress, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2024-11/2024_Annual_Report_to_Congress.pdf, 138–139. With respect to Cuba specifically, the 2025 SOUTHCOM Posture Statement stated that the island “serves as a proximate location for intelligence gathering and force projection by our adversaries.”41“Statement of Admiral Alvin Holsey, Commander, United States Southern Command,” Senate Armed Services Committee, February 13, 2025, https://www.southcom.mil/Portals/7/Documents/Posture%20Statements/2025_SOUTHCOM_Posture_Statement_FINAL.pdf?ver=5L0oh0wyNgJ2_qzelc6wKQ%3d%3d, 14. This assessment came amid public reports that China was building four eavesdropping stations in Cuba to intercept U.S. military communications.42Matthew P. Funaiole et al., “China’s Intelligence Footprint in Cuba: New Evidence and Implications for U.S. Security,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, December 6, 2024, https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinas-intelligence-footprint-cuba-new-evidence-and-implications-us-security.

U.S. officials are likewise concerned about Russia’s activities in the Western Hemisphere. In 2024, General Laura Richardson, the commander of U.S. Southern Command, testified that Russia was “leveraging its diplomats and periodic military force projection to maintain and gain influence” in the region.43“Statement of General Laura J. Richardson, Commander, United States Southern Command,” Senate Armed Services Committee, March 14, 2024, https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/hearings/to-receive-testimony-on-posture-of-united-states-northern-command-and-united-states-southern-command-in-review-of-the-defense-authorization-request-for-fiscal-year-2025-and-the-future-years-defense-program, 10. Recent developments have inflamed this sentiment. In June 2024, four Russian warships docked in Cuba for planned naval exercises.44Samantha Schmidt et al., “What are Russian warships doing in the Caribbean?” Washington Post, June 12, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2024/06/12/russia-navy-ships-florida-cuba-caribbean/.

But Cuba is doing little to help China or Russia pose a threat to the United States. Cuba’s relationship with Russia is more symbolic than substantive. Economic agreements between the two sides have floundered due to financing problems and a lack of implementation.45Dave Sherwood, “China is quietly supplanting Russia as Cuba’s main benefactor,” Reuters, June 30, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/china-is-quietly-supplanting-russia-cubas-main-benefactor-2025-06-30/. Russian oil exports to Cuba have been insufficient to alleviate the island’s frequent power shortages.46Orlando Matos and Carmen Sesin, “Power goes out on entire island of Cuba, leaving 10 million people without electricity,” NBC News, October 18, 2024, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/power-goes-entire-island-cuba-leaving-10-million-people-dark-rcna176169. Despite significant press coverage at the time, Russia’s June 2024 naval port visit to Cuba lasted only a few days and was motivated more by Vladimir Putin’s desire to send the United States a message over its ongoing support for Ukraine than a concerted bid to establish a Russian military presence in the Caribbean.47Ariel González Levaggi and Vladimir Rouvinski, “The Kremlin’s Caribbean Gambit: A Great Power Competition,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 24, 2024, https://www.csis.org/analysis/kremlins-caribbean-gambit-great-power-competition-spillover. Even if Russia was less tied down in Ukraine and could address the military and logistical difficulties of such a deployment, it could backfire on Moscow by pushing Latin American states closer to Washington just as it did during the Cold War.

Cuba-China ties are no more impressive. Yes, Cuba is a signatory to China’s Belt and Road Initiative, has signed infrastructure and energy deals with Beijing, and gave China’s National Petroleum Corporation a stake in the drilling of Cuban oil.48“China-Cuba: Bilateral Trade and Investment Prospects,” China Briefing, November 25, 2022, https://www.china-briefing.com/news/china-cuba-bilateral-trade-and-investment-prospects/. Yet compared to larger, more promising markets in Latin America, Cuba is a minor blip on China’s economic radar. At approximately $862 million in 2023, China’s bilateral trade with the island is only a third of its commerce with El Salvador, whose population is 60 percent that of Cuba’s.49“El Salvador-China trade relations,” Observatory of Economic Complexity, https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-country/chn/partner/cub. Cuban exports to China of raw materials such as nickel and cobalt will only go so far given the presence of alternative sources in the supply chain as well as the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) long-standing policy of diversifying suppliers. The Chinese companies that are running projects in Cuba have been frustrated by Havana’s inability to pay its debts.50Ed Augustin, “’China is not Cuba’s sugar daddy’: ties between communist nations weaken,” Financial Times, October 13, 2024, https://www.ft.com/content/9ca0a495-d5d9-4cc5-acf5-43f42a9128b4.

Cuba’s military ties with China are piecemeal and center on meetings between their respective military bureaucracies. Joint training exercises are hard to come by and no Chinese military bases exist on the island. Nor does China appear particularly interested in a formal alliance with Cuba that would limit its freedom of movement and force it to play the role of Cuba’s security provider.51Evan N. Resnick and Hannah Elyse Sworn, “China and the Alliance Allergy of Rising Powers,” War on the Rocks, May 30, 2023, https://warontherocks.com/2023/05/china-and-the-alliance-allergy-of-rising-powers/. Such an out-of-area mission would distract the CCP from its core priority of becoming the dominant power in East Asia.

Reports in 2024 about Chinese surveillance stations in Cuba raised concerns in U.S. national security circles, but this can hardly be called a dire situation for the United States.52Matthew P. Funaiole, Brian Hart, Aidan Powers-Riggs, and Joseph S. Bermudez, Jr., “At the Doorstep: A Snapshot of New Activity at Cuban Spy Sites,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, May 6, 2025, https://features.csis.org/hiddenreach/snapshots/cuba-china-cdaa-base/. Listening posts on the island are not new: the Soviet Union (and then Russia) operated its largest surveillance facility in the Western Hemisphere at Lourdes, Cuba, for decades.53Michael Wines, “Russia Closing 2 Major Posts for Snooping, One in Cuba,” New York Times, October 18, 2001, https://www.nytimes.com/2001/10/18/world/russia-closing-2-major-posts-for-snooping-one-in-cuba.html. Granted, if China is operating a radar facility there, it might gain greater insight into the movement of U.S. aircraft and ships in the region. Still, such information has limited import since any U.S.-China war would be fought near China, not the Caribbean. U.S. intelligence operations in East Asia are therefore far more concerning for Beijing than any challenges the United States would face from Chinese surveillance activities in Cuba.

Moreover, it isn’t clear why the United States should worry even if China or Russia established a military base in Cuba. The same rules of mutually assured destruction that prevailed during the Cold War would continue to apply today. Just as the balance of power was stable after Soviet troops and missiles landed in Cuba, the United States’ superior power position in the Western Hemisphere will remain intact regardless of foreign military deployments to the island.

The benefits of a U.S. opening to Cuba

Given Cuba’s marginal importance to U.S. grand strategy in the Western Hemisphere, one might argue that the United States can keep the status quo indefinitely with few costs. This is true in a strictly security sense, but staying the course would perpetuate failed policies that are a net loser for the United States. Because Cuba’s position is so weak, the Trump administration can reform its policy without worrying about risks to U.S. national security. While the benefits of a U.S.-Cuba rapprochement might not be groundbreaking, such a course is still in the U.S. national interest for several reasons.

First, the U.S. embargo, in addition to the economic restrictions enacted by the Trump administration, ties the hands of U.S. businesses. One study by Johns Hopkins University finds that U.S. companies lose approximately $2 billion in sales every year courtesy of the U.S. sanctions regime. This is a relatively paltry sum compared to other markets but still an unnecessary loss that gives competitors, particularly in Europe and China, an advantage.54“Blockade on Cuba Costs US Economy More,” Council on Hemispheric Affairs, January 12, 2009, https://coha.org/blockade-on-cuba-costs-us-economy-more/. The lost revenue is especially galling for the U.S. agricultural and tourism industries: Cuba imports approximately 80 percent of its food products, a need U.S. farmers could easily fill.55“Factsheet: Why engagement with Cuba benefits the United States,” Washington Office on Latin America, November 30, 2016, https://www.wola.org/analysis/factsheet-engagement-cuba-benefits-united-states/; https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46791. It is no wonder that the U.S. business community has led the charge for a removal of the Cuba embargo—the island is an untapped market close to U.S. shores.

Cuba is also a source of rare earth metals, in particular cobalt and zinc, which the United States increasingly views as critical for future economic development. China has used its dominance in rare earth mining to pressure the United States in trade talks.56China controls approximately 70 percent of the world’s rare earths mining. See “2023 Minerals Yearbook,” U.S. Geological Survey, June 2025, https://pubs.usgs.gov/myb/vol3/2023/myb3-2023-cuba.pdf. Like other rare earths, the United States considers the global cobalt supply chain to be at risk. Cuba’s sizable reserves of the mineral would alleviate some of these shortages, but the embargo has placed them off-limits to the United States.57H. Michael Erisman, “Cuban Cobalt: A Gateway to Strategic Minerals Politics?” International Journal of Cuban Studies 14, no. 2 (2022): 347–348.

Beyond economic returns, reforming U.S. policy on Cuba would help the Trump administration better manage two issues it cares about: drug trafficking and irregular migration. On the former, Cuba has traditionally been an effective partner, with the Cuban government viewing drugs as detrimental to an orderly society.58In October 2025, Cuban authorities arrested Zhi Dong Zhang, a Chinese drug trafficker who smuggled fentanyl precursors into Mexico on behalf of the Sinaloa and Jalisco New Generation Cartels. Zhang was extradited to Mexico, which in turn extradited him to the United States. His case is pending. Thomas Graham, “Brother Wang, a global manhunt and the Chinese-Mexican drug nexus,” Guardian, November 20, 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/nov/20/zhi-dong-zhang-mexico-drugs-china. The State Department’s 2024 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report states that the Cuban Coast Guard regularly cooperates with the U.S. Coast Guard on drug interdictions.59“2024 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report,” U.S. Department of State, March 2024, https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/2024-INCSR-Vol-1-Drug-and-Chemical-Control-Accessible-Version.pdf, 170. The Trump administration removed Cuba in the 2025 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report, although the reasoning behind this was not disclosed. Whether this trend continues today is unclear, but logic dictates that collaboration on counter-narcotics missions and intelligence sharing is more likely if the overall U.S.-Cuba relationship improves.

The same can be said about migration. During the Obama administration’s U.S.-Cuba rapprochement, a special working group on migration was established between U.S. and Cuban officials to determine annual quotas for the number of Cuban immigrants allowed to emigrate to the United States, exchange information on people smuggling routes, and establish procedures when Cuban migrants are intercepted at sea. But this engagement weakened after the Obama-era reconciliation was reversed during Trump’s first term. Talks on migration have since stalled, and the problem has only worsened with time. About 425,000 Cuban migrants appeared at U.S. ports of entry in 2022–2023, a number larger than during the 1980 Mariel boatlift and the 1994 Balsero crisis combined.60Eric Bazail-Eimil, “Record-breaking numbers of Cuban migrants entered the U.S. in 2022-23,” Politico, October 24, 2023, https://www.politico.com/news/2023/10/24/record-breaking-numbers-of-cuban-migrants-entered-the-u-s-in-2022-23-00123346; for more on past Cuban migration crises, see LeoGrande and Kornbluh’s Back Channel to Cuba. The migration wave is only aggravated by tightening U.S. sanctions, which have further contracted the Cuban economy and spurred working-age Cubans to depart the island. In other words, U.S. policies are intensifying the very migration the United States wants to curtail.

Opening up to Cuba would hold diplomatic dividends for the United States as well. The 60-year-old embargo has been a consistent thorn in the side of Washington’s broader policy in Latin America. The vast majority of the region’s governments view U.S. economic restrictions on Cuba as a policy whose time has long since passed. The United States finds itself isolated in international forums when the topic of Cuba is on the agenda.61In 2023, 12 Latin American states, including traditional U.S. security partners like Mexico, Colombia, Ecuador, and Panama, gathered for a summit in part to denounce U.S. sanctions on Cuba (as well as Venezuela) as unjust. Zedryk Raziel, “Latin American countries urge US to lift sanctions on Cuba and Venezuela to curb migration,” El Pais, October 23, 2023, https://english.elpais.com/international/2023-10-23/latin-american-countries-urge-us-to-lift-sanctions-on-cuba-and-venezuela-to-curb-migration.html. In October 2025, the UN General Assembly voted 165–7 (with 12 abstentions) to call for an end to the U.S. embargo. “Necessity of ending the economic, commercial and financial embargo imposed by the United States of America against Cuba,” UN General Assembly Resolution, October 7, 2025, https://docs.un.org/A/80/L.6.

Finally, as a matter of policy, comprehensive sanctions regimes have historically failed to achieve U.S. foreign policy goals—and do little to promote the internal democratic reforms they’re supposed to foster. In fact, research suggests the opposite: economic sanctions worsen the prospects of democracy in a targeted country and mobilize the regime’s core supporters against a foreign interloper.62Dursun Peksen and Cooper Drury, “Coercive or Corrosive: The Negative Impact of Economic Sanctions on Democracy,” International Interactions 36, no. 3 (2010): 240–264; Sabastian Hellmeier, “How foreign pressure affects mass mobilization in favor of authoritarian regimes,” European Journal of International Relations 27, no. 2 (2021): 450–477. In addition, sanctions frequently fail to extract major concessions or changes in behavior from the targeted state.63Gary Clyde Hufbauer, Jeffrey J. Schott, Kimberly Ann Elliott, and Barbara Oegg, Economic Sanctions Reconsidered: Third Edition (Washington, D.C.: Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2009). The UN-enforced sanctions regime against Saddam Hussein’s government in Iraq, for instance, did not compel Iraq to cooperate with UN inspectors seeking to verify Iraq’s disarmament. U.S. and UN sanctions were unable to convince the Iranian government to abandon its uranium enrichment program. And North Korea remains a de facto nuclear weapons state despite enduring one of the strongest UN sanctions efforts in history. Similar failures can be seen in Cuba where doubling down on the same policy will only produce the same results.

Exploring a diplomatic rapprochement with Cuba would begin removing the moral stain associated with the current policy, which in essence immiserates an entire country for the sins of its leaders. Despite U.S. officials justifying the embargo as a way to extract political concessions from the Cuban leadership, the embargo collectively punishes a population that has very little impact on what Cuban policymakers do. Punitive U.S. measures are actually useful for the Cuban government, which can conveniently point to them as the root cause of Cuba’s economic misery. This isn’t the first time an authoritarian state has used this strategy: Iran, North Korea, Russia, Venezuela, and Syria under the Assad regime have to various degrees blamed the United States to distract from their own mistakes.

Move Cuba away from China and Russia

As mentioned in the preceding section, U.S. defense officials are increasingly alarmed at the prospect of China and Russia bolstering their presence in the Western Hemisphere. To date, Cuba’s relations with both powers are concentrated on sporadic military-to-military exchanges, high-profile visits, and largely symbolic agreements that aim to boost cooperation. Still, U.S. policy documents, including numerous U.S. military posture reviews, continue to harp on the theme. The U.S. National Security Strategy’s prioritization of the Western Hemisphere suggests that great power competition in the U.S. sphere of influence will remain at the forefront of the Trump administration’s foreign policy plans.64Carla Babb, “New Pentagon strategy to focus on homeland, Western Hemisphere,” Defense News, September 25, 2025, https://www.defensenews.com/pentagon/2025/09/25/new-pentagon-strategy-to-focus-on-homeland-western-hemisphere/.

Yet if the U.S. objective is to limit Chinese and Russian influence in the United States’ own backyard, then continuing to treat Cuba as an adversary instead of a normal state only complicates the job. By trying to isolate Cuba, the U.S. encourages it to partner with other great powers to defend its security interests. This is precisely what Cuba did during the Cold War: President John F. Kennedy’s economic embargo solidified rather than weakened the Cuban government’s strategic relationship with the Soviet Union.

It should not come as a surprise that small states searching for security in the face of a stronger adversary will court allies.65See Morgenthau, “Alliances in Theory and Practice,” in Arnold Wolters, Alliance Policy in the Cold War (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1959): 184–212; Stephen Walt, The Origins of Alliances (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1987). Although it’s a stretch to say Cuba has an alliance with either China or Russia, the principle still applies. Cuba’s threat perception with respect to the United States has led it to strengthen ties with states that share a negative view of U.S. power.

This development has been confirmed on both sides of the U.S.-Cuba divide. In a 2024 interview, Cuban Foreign Minister Bruno Rodríguez Parrilla pegged Havana’s growing engagement with China and Russia to its depreciating relationship with the United States.66Tom O’Connor, “Exclusive: Cuba Warns US Pressure Drives Closer Ties With China and Russia,” Newsweek, September 27, 2024, https://www.newsweek.com/exclusive-cuba-warns-us-pressure-drives-closer-ties-china-russia-1959936. Retired Ambassador Jeffrey DeLaurentis, who served as charge d’affaires at the U.S. Embassy in Havana during the Obama administration, stated that the U.S. decision to move away from the rapprochement implemented in 2015–2016 enabled China and Russia to strengthen their influence on the island to Washington’s detriment.67“The Opening of Cuba with Ambassador Jeffrey DeLaurentis,” Stimson Center, March 18, 2025, https://www.stimson.org/2025/the-opening-of-cuba-with-ambassador-jeffrey-delaurentis/.

None of this is to say that strengthening U.S. relations with Cuba will magically result in the Cuban government cutting relations with U.S. adversaries. From Cuba’s perspective, this would be ill-advised given the foreign policy changes that can occur upon the entrance of a new U.S. administration.68In June 2017, five months after assuming office, Trump reversed Obama’s Cuba policy via executive order. “Strengthening the Policy of the United States Toward Cuba,” White House, June 16, 2017, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2017/10/20/2017-22928/strengthening-the-policy-of-the-united-states-toward-cuba. As a small state with resource constraints in desperate need of foreign investment, Cuba is more likely to try to sustain positive ties with Beijing and Moscow even if a diplomatic opening with the United States is possible.

Even so, reconciling with Cuba will at least begin the process of reducing the Cuban government’s high threat assessment vis-à-vis the United States, offer the island another option as it navigates relations with the great powers, and give Cuba a reason to reassess its current foreign policy. For a neighbor only 90 miles off the coast of Florida, this is an opportunity worth taking.

Recommendations

Although foreign policy is frequently treated as the president’s prerogative, U.S. policy with Cuba is unique. Congress codified the U.S. embargo on the island in the 1992 Cuban Democracy Act, limiting the executive branch’s ability to lift it unilaterally.69National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1993, 102nd Congress, October 23, 1992, https://1997-2001.state.gov/www/regions/wha/cuba/democ_act_1992.html, 2575–2581. In 1996, Congress passed another law establishing a list of requirements the Cuban government must meet—including the legalization of all political activity in Cuba, free and fair elections, the establishment of an independent judiciary, and market-style economic reforms—before any U.S. president can suspend the embargo.70No U.S. president to date has been able to certify those conditions, and even if one did, Congress would have an opportunity to override the president’s determination. Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act of 1996, 104th Congress, March 12, 1996, https://www.congress.gov/104/statute/STATUTE-110/STATUTE-110-Pg785.pdf.

Despite these statutory limitations, U.S. presidents retain the power to chip away at the embargo if they believe it is in the U.S. national security interest. The executive branch retains some discretion within the law, and presidents in the past have carved out exemptions to the embargo to extract human rights concessions from the Cuban government or open opportunities for the Cuban private sector.71President Bill Clinton loosened U.S. travel restrictions and remittance caps to Cuba during his second term less than two years after he signed the 1996 Helms-Burton Act. President Barack Obama embarked upon diplomatic normalization in 2015 and 2016 despite considerable opposition in Congress. And in 2024, President Joe Biden permitted Cuban entrepreneurs in the private sector to open a U.S. bank account. See, “Treasury Amends Regulations to Increase Support for the Cuban People and Independent Private Sector Entrepreneurs,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, May 28, 2024, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy2374.

In an ideal world, Congress would overturn the embargo statutorily. In reality, this is unlikely due in part to the persistence of a strong Cuban-American lobby in a key U.S. swing state. Nevertheless, the Trump administration can pursue reform if so chooses, and the same goes for any future U.S. administration. There are some commonsense steps the United States can take to begin the process of rebuilding bilateral relations with Cuba, none of which are high-risk to the U.S. position in the Western Hemisphere.

First, the United States should lift caps and banking limitations on remittances to Cuba. Prohibiting such activity hurts the Cuban population far more than the Cuban government. With the Cuban economy contracting, poverty rates rising, and the cost of basic necessities increasing, many ordinary Cubans rely on remittances from relatives in the United States to survive. These remittances declined by almost 70 percent between 2018–2020 after the Trump administration imposed a cap on the amount of money Cuban Americans can send their relatives on the island.72Manuel Orozco, “Remittances to Cuba and the Marketplace in 2024,” Inter-American Dialogue, March 2024, https://thedialogue.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Remittances-to-Cuba-and-the-Marketplace-in-2024-1.pdf, 7. Although remittances rose after the Biden administration reformed the rules, the restrictions currently in place have deterred further transactions.73Jim Wyss, “Western Union Halts Money Transfers to Cuba Citing New Sanctions,” Bloomberg, February 10, 2025, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-02-10/western-union-halts-money-transfers-to-cuba-citing-new-sanctions.

Second, in the event U.S. policymakers decide to improve relations with Havana, the Treasury Department should issue concrete, clear guidelines on what economic activity in Cuba is and is not permissible for U.S. businesses. The long list of Cuban government- and military-linked subsidiaries, financial institutions, and associated entities that are targeted for U.S. sanctions is unwieldy and compels U.S. businesses to forgo Cuba as an export market for fear of running afoul of U.S. law. As a first step, the United States can return to its earlier policy of allowing small-scale, independent Cuban business owners to access the U.S. financial system for loans and to process payments. This would not only help grow the Cuban private sector but also give the United States greater visibility into transactions.74John McIntire and Ricardo Herrero, “The Truth About Cuba’s Private Sector,” Americas Quarterly, July 12, 2024, https://americasquarterly.org/article/the-truth-about-cubas-private-sector/.

Third, the U.S. embassy in Havana should be adequately staffed and resourced. A U.S. ambassador should represent U.S. interests in Cuba, not just a charge d’affaires, as is presently the case. This can occur without a full normalization of relations and will send a message to Cuba that the United States is at least interested in exploring high-level engagement on issues of mutual concern. The Cuban government is likely to ask for an increase in Cuban representation at its own embassy in Washington in return. But this would be less a U.S. concession than an opportunity to regularize engagement between the two countries.

Fourth, the working groups established between the United States and Cuba during the Obama-era normalization period should be resurrected to manage issues that have made a productive working relationship difficult to sustain. As noted above, the two states have a mutual interest in sharing intelligence on migration smuggling and drug trafficking, which should be institutionalized as much as possible. Critically, progress in these areas should not be held hostage to other areas of dispute, such as the extent of political reform inside Cuba or U.S. foreign policy in Latin America, that are irreconcilable for the time being. Linkage has spoiled agreements and understandings on migration in the past.

Finally, the United States should officially drop regime change as the overall objective of its Cuba policy. Predictably, this will be categorized by Cuba hardliners as appeasement. But the United States engages with plenty of unsavory states whose democratic standards are just as offensive as Cuba’s. U.S. policymakers do this not as a favor to these states but rather as a necessary step to meet U.S. security interests and preserve geopolitical flexibility. U.S. relations with Cuba should be no special exception.

An irritant, not a threat

The United States maintains the paramount position in the Western Hemisphere. Hyperbolic commentary about Chinese or Russian encroachment in partnership with a hostile Cuba does not change this reality. Cuba is at worst an irritant to the United States, and a weak one at that. Paradoxically, it is because Cuba is so weak that the United States can run the low risk of replacing its policy with one that has a greater chance of accomplishing the three objectives U.S. officials claim to want: stability in the Caribbean, more markets for U.S. businesses, and preserving the U.S. sphere of influence. While the benefits of reform are limited, they still exceed whatever deliverables the United States is receiving with today’s outdated policy.

Endnotes

- 1“National Security Strategy of the United States,” White House, November 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/2025-National-Security-Strategy.pdf.

- 2Susan Eckstein, “How Cubans Transformed Florida Politics and Gained National Influence,” in Viviana Díaz Balsera and Rachel A. May, La Florida: Five Hundred Years of Hispanic Presence (Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida, 2014): 263–284.

- 3“Initial Rescissions of Harmful Executive Orders and Actions,” White House, January 20, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/initial-rescissions-of-harmful-executive-orders-and-actions/.

- 4“National Security Presidential Memorandum/NSPM-5,” White House, June 30, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/06/national-security-presidential-memorandum-nspm-5/.

- 5Nora Gámez Torres, “In a first, U.S. sanctions Cuba leader Miguel Díaz Canel for human rights violations,” Miami Herald, July 11, 2025, https://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/cuba/article310412200.html.

- 6Carmen Sesin and Orlando Matos, “Trump admin says it won’t hold migration talks with Cuba,” NBC News, April 25, 2025, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/trump-admin-wont-hold-migration-talks-cuba-rcna203035.

- 7Ryan Mancini, “Rubio sends warning to Cuba’s leaders after Maduro’s removal: ‘I’d be concerned,’” The Hill, January 3, 2026, [https://thehill.com/homenews/administration/5671259-rubio-warns-cuba-maduro-capture/](https://thehill.com/homenews/administration/5671259-rubio-warns-cuba-maduro-capture/).

- 8“Statement of Admiral Alvin Holsey, Commander, United States Southern Command,” Senate Armed Services Committee, February 13, 2025, https://www.southcom.mil/Portals/7/Documents/Posture%20Statements/2025_SOUTHCOM_Posture_Statement_FINAL.pdf?ver=5L0oh0wyNgJ2_qzelc6wKQ%3d%3d, 14.

- 9“Treasury and Commerce Implement Changes to Cuba Sanctions Rules,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, June 4, 2019, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm700.

- 10Alan McPherson, “The Limits of Populist Diplomacy: Fidel Castro’s April 1959 Trip to North America,” Diplomacy & Statecraft 18, no. 1 (2007): 237–268.

- 11“Editorial Note,” Foreign Relations of the United States, 1958–1960, Cuba, Volume VI, State Department Office of the Historian, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1958-60v06/d287.

- 12Tad Szulc, “Cuba Exploiting Discord with U.S.; Relations at Low Point and Seem Due to Remain So — Washington Called Foe,” New York Times, December 20, 1959, https://www.nytimes.com/1959/12/20/archives/cuba-exploiting-discord-with-us-relations-at-low-point-and-seem-due.html.

- 13In November 1960, a month before Eisenhower instituted a ban on Cuban sugar imports, he wrote a letter to UK Prime Minister Harold Macmillan explaining why those measures were needed to expel Soviet influence from the island. As Eisenhower wrote, “the Castro Government is now fully committed to the Bloc. We cannot prudently follow policies looking to a reform of Castro’s attitude and we must rely, frankly, on creating conditions in which democratically minded and Western-oriented Cubans can assert themselves and regain control of the island’s policies and destinies.” See “Letter From President Eisenhower to Prime Minister Macmillan,” Foreign Relations of the United States, 1958–1960, Cuba, Volume VI, State Department Office of the Historian, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1958-60v06/d551; Michael Grow, U.S. Presidents and Latin American Interventions (Lawrence, Kansas: University of Kansas Press 2008): 41–45.

- 14“Proclamation 3447—Embargo on All Trade with Cuba,” White House, February 3, 1962, accessed at https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/proclamation-3447-embargo-all-trade-with-cuba; “Memorandum for the Special Group from Brigadier General Landsale,” Central Intelligence Agency, August 6, 1962, accessed at https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/operation%20mongoose%20-%20futu%5B15436924%5D.pdf.

- 15Duccio Basosi, “‘Something that apparently troubles the Cubans significantly’: Jimmy Carter’s attempt to pressure Cuba ‘out of Africa’ through the Non-Aligned Movement, 1977–78,” Cold War History 24, no. 3 (2004): 359–377.

- 16“Address Before a Joint Session of the Congress on Central America,” Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, April 27, 1983, https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/speech/address-joint-session-congress-central-america.

- 17Benjamin H. Friedman, “The Terrible ‘Ifs’,” Regulation (Winter 2008): 32–40, https://object.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/serials/files/regulation/2007/12/v30n4-1 .pdf.

- 18Robert Jervis, “The Nuclear Revolution and the Common Defense,” Political Science Quarterly 101, no. 5 (1986): 689–703.

- 19William D’Ambruoso, “The Restraining Effect of Nuclear Deterrence,” Defense Priorities, June 16, 2023, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/the-restraining-effect-of-nuclear-deterrence/#continuity-in-the-new-nuclear-age.

- 20According to the U.S. Department of Energy, the United States possessed more than 25,000 nuclear weapons at the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis. For more, see “Transparency in the U.S. Nuclear Weapons Stockpile,” U.S. Department of Energy, https://www.energy.gov/nnsa/transparency-us-nuclear-weapons-stockpile.

- 21“The Jupiter Missiles and the Endgame of the Cuban Missile Crisis, 60 Years Ago,” National Security Archive, February 16, 2023, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/briefing-book/cuban-missile-crisis-nuclear-vault/2023-02-16/jupiter-missiles-and-endgame-cuban.

- 22Raymond Garthoff, Reflections on the Cuban Missile Crisis (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 1989): 207.

- 23Serhii Plotkhy, Nuclear Folly: A History of the Cuban Missile Crisis (New York: W.W Norton & Company, 2021): 52–53, 56.

- 24Evan N. Resnick, “Interests, ideologies, and great power spheres of influence,” European Journal of International Relations 29, no. 3 (2022): 563–588.

- 25Stephen Van Evera, “Why Europe matters, why the third world doesn’t: American grand strategy after the cold war,” Journal of Strategic Studies 13, no. 2 (1990): 1–51.

- 26Van Evera, “Why Europe matters,” 17.

- 27“Letter to the Speaker of the House of Representatives on the Situation in Angola,” White House, January 27, 1976, accessed at https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/letter-the-speaker-the-house-representatives-the-situation-angola; “Washington Special Actions Group Meeting,” White House, March 24, 1976, accessed at https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB487/docs/03%20-%20Washington%20Special%20Actions%20Group%20Meeting,%20Cuba,%20March%2024,%201976.pdf.

- 28Kissinger was a central player in these arguments as well. See “Report of the National Bipartisan Commission on Central America,” January 10, 1984, accessed at https://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/federal_documents/8/.

- 29Piero Gleijeses, “Moscow’s Proxy? Cuba and Africa 1975–1988,” Journal of Cold War Studies 8, no. 4 (2006): 98–146.

- 30William M. LeoGrande, Our Own Backyard (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000) 88.

- 31While Cuba delivered a diplomatic proposal to the Soviets in a bid to advance diplomacy in Central America, Havana’s roadmap was rendered irrelevant after the Sandinistas lost the 1990 presidential election in Nicaragua and handed over power. See, William M. LeoGrande and Peter Kornbluh, Back Channel to Cuba: The Hidden History of Negotiations Between Washington and Havana (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014): 259–261.

- 32Carla Gloria Colomé, “Carmelo Mesa-Lago: ‘Today’s Cuba is a catastrophe,’” El Pais, June 16, 2024, https://english.elpais.com/international/2024-06-16/carmelo-mesa-lago-todays-cuba-is-a-catastrophe.html?outputType=amp; for more, see “Carmelo Mesa-Lago, “The Economic Effects on Cuba of the Downfall of Socialism in the USSR and in Eastern Europe” in Carmelo Mesa-Lago, Cuba After the Cold War (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1993): 133–196.

- 33David Sherwood, “Cuba tourism struggles as blackouts and shortages deter visitors,” Reuters, December 19, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/cuba-tourism-struggles-blackouts-shortages-deter-visitors-2024-12-19/.

- 34Nora Gámez Torres, “Minister ignites uproar saying Cuba has no beggars, only people ‘disguised as beggars,’” Miami Herald, July 16, 2025, https://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/cuba/article310724920.html.

- 35Frances Robles et al, “10 Years Ago, a U.S. Thaw Fueled Cuban Dreams. Now Hope Is Lost,” New York Times, December 27, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/12/27/world/americas/obama-us-thaw-cuba-crisis.html.

- 36“Cuban Armed Forces and the Soviet Military Presence,” United States Department of State, August 1982, accessed at https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP85M00363R001403210041-0.pdf.

- 37Hal Klepak, ”Reflections on U.S.-Cuba Military-to-Military Contacts,” Strategic Forums 95 (2016), accessed at https://digitalcommons.ndu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1017&context=strategic-forums.

- 38“The Cuban Threat to U.S. National Security,” U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency, November 19, 1997, accessed at https://irp.fas.org/dia/product/980507-dia-cubarpt.htm.

- 39As the 2022 NSS states, the United States “will support effective democratic governance responsible to citizen needs, defend human rights and combat gender-based balance, tackle corruption, and protect against external interference or coercion, including from the PRC [China], Russia, or Iran.” See “National Security Strategy,” White House, October 2022, https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Biden-Harris-Administrations-National-Security-Strategy-10.2022.pdf, 41.

- 40“2024 Report to Congress of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission,” U.S. Congress, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2024-11/2024_Annual_Report_to_Congress.pdf, 138–139.

- 41“Statement of Admiral Alvin Holsey, Commander, United States Southern Command,” Senate Armed Services Committee, February 13, 2025, https://www.southcom.mil/Portals/7/Documents/Posture%20Statements/2025_SOUTHCOM_Posture_Statement_FINAL.pdf?ver=5L0oh0wyNgJ2_qzelc6wKQ%3d%3d, 14.

- 42Matthew P. Funaiole et al., “China’s Intelligence Footprint in Cuba: New Evidence and Implications for U.S. Security,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, December 6, 2024, https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinas-intelligence-footprint-cuba-new-evidence-and-implications-us-security.

- 43“Statement of General Laura J. Richardson, Commander, United States Southern Command,” Senate Armed Services Committee, March 14, 2024, https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/hearings/to-receive-testimony-on-posture-of-united-states-northern-command-and-united-states-southern-command-in-review-of-the-defense-authorization-request-for-fiscal-year-2025-and-the-future-years-defense-program, 10.

- 44Samantha Schmidt et al., “What are Russian warships doing in the Caribbean?” Washington Post, June 12, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2024/06/12/russia-navy-ships-florida-cuba-caribbean/.

- 45Dave Sherwood, “China is quietly supplanting Russia as Cuba’s main benefactor,” Reuters, June 30, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/china-is-quietly-supplanting-russia-cubas-main-benefactor-2025-06-30/.

- 46Orlando Matos and Carmen Sesin, “Power goes out on entire island of Cuba, leaving 10 million people without electricity,” NBC News, October 18, 2024, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/power-goes-entire-island-cuba-leaving-10-million-people-dark-rcna176169.

- 47Ariel González Levaggi and Vladimir Rouvinski, “The Kremlin’s Caribbean Gambit: A Great Power Competition,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 24, 2024, https://www.csis.org/analysis/kremlins-caribbean-gambit-great-power-competition-spillover.

- 48“China-Cuba: Bilateral Trade and Investment Prospects,” China Briefing, November 25, 2022, https://www.china-briefing.com/news/china-cuba-bilateral-trade-and-investment-prospects/.

- 49“El Salvador-China trade relations,” Observatory of Economic Complexity, https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-country/chn/partner/cub.

- 50Ed Augustin, “’China is not Cuba’s sugar daddy’: ties between communist nations weaken,” Financial Times, October 13, 2024, https://www.ft.com/content/9ca0a495-d5d9-4cc5-acf5-43f42a9128b4.

- 51Evan N. Resnick and Hannah Elyse Sworn, “China and the Alliance Allergy of Rising Powers,” War on the Rocks, May 30, 2023, https://warontherocks.com/2023/05/china-and-the-alliance-allergy-of-rising-powers/.

- 52Matthew P. Funaiole, Brian Hart, Aidan Powers-Riggs, and Joseph S. Bermudez, Jr., “At the Doorstep: A Snapshot of New Activity at Cuban Spy Sites,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, May 6, 2025, https://features.csis.org/hiddenreach/snapshots/cuba-china-cdaa-base/.

- 53Michael Wines, “Russia Closing 2 Major Posts for Snooping, One in Cuba,” New York Times, October 18, 2001, https://www.nytimes.com/2001/10/18/world/russia-closing-2-major-posts-for-snooping-one-in-cuba.html.

- 54“Blockade on Cuba Costs US Economy More,” Council on Hemispheric Affairs, January 12, 2009, https://coha.org/blockade-on-cuba-costs-us-economy-more/.

- 55“Factsheet: Why engagement with Cuba benefits the United States,” Washington Office on Latin America, November 30, 2016, https://www.wola.org/analysis/factsheet-engagement-cuba-benefits-united-states/; https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46791.

- 56China controls approximately 70 percent of the world’s rare earths mining. See “2023 Minerals Yearbook,” U.S. Geological Survey, June 2025, https://pubs.usgs.gov/myb/vol3/2023/myb3-2023-cuba.pdf.

- 57H. Michael Erisman, “Cuban Cobalt: A Gateway to Strategic Minerals Politics?” International Journal of Cuban Studies 14, no. 2 (2022): 347–348.

- 58In October 2025, Cuban authorities arrested Zhi Dong Zhang, a Chinese drug trafficker who smuggled fentanyl precursors into Mexico on behalf of the Sinaloa and Jalisco New Generation Cartels. Zhang was extradited to Mexico, which in turn extradited him to the United States. His case is pending. Thomas Graham, “Brother Wang, a global manhunt and the Chinese-Mexican drug nexus,” Guardian, November 20, 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/nov/20/zhi-dong-zhang-mexico-drugs-china.

- 59“2024 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report,” U.S. Department of State, March 2024, https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/2024-INCSR-Vol-1-Drug-and-Chemical-Control-Accessible-Version.pdf, 170. The Trump administration removed Cuba in the 2025 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report, although the reasoning behind this was not disclosed.

- 60Eric Bazail-Eimil, “Record-breaking numbers of Cuban migrants entered the U.S. in 2022-23,” Politico, October 24, 2023, https://www.politico.com/news/2023/10/24/record-breaking-numbers-of-cuban-migrants-entered-the-u-s-in-2022-23-00123346; for more on past Cuban migration crises, see LeoGrande and Kornbluh’s Back Channel to Cuba.

- 61In 2023, 12 Latin American states, including traditional U.S. security partners like Mexico, Colombia, Ecuador, and Panama, gathered for a summit in part to denounce U.S. sanctions on Cuba (as well as Venezuela) as unjust. Zedryk Raziel, “Latin American countries urge US to lift sanctions on Cuba and Venezuela to curb migration,” El Pais, October 23, 2023, https://english.elpais.com/international/2023-10-23/latin-american-countries-urge-us-to-lift-sanctions-on-cuba-and-venezuela-to-curb-migration.html. In October 2025, the UN General Assembly voted 165–7 (with 12 abstentions) to call for an end to the U.S. embargo. “Necessity of ending the economic, commercial and financial embargo imposed by the United States of America against Cuba,” UN General Assembly Resolution, October 7, 2025, https://docs.un.org/A/80/L.6.

- 62Dursun Peksen and Cooper Drury, “Coercive or Corrosive: The Negative Impact of Economic Sanctions on Democracy,” International Interactions 36, no. 3 (2010): 240–264; Sabastian Hellmeier, “How foreign pressure affects mass mobilization in favor of authoritarian regimes,” European Journal of International Relations 27, no. 2 (2021): 450–477.

- 63Gary Clyde Hufbauer, Jeffrey J. Schott, Kimberly Ann Elliott, and Barbara Oegg, Economic Sanctions Reconsidered: Third Edition (Washington, D.C.: Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2009).

- 64Carla Babb, “New Pentagon strategy to focus on homeland, Western Hemisphere,” Defense News, September 25, 2025, https://www.defensenews.com/pentagon/2025/09/25/new-pentagon-strategy-to-focus-on-homeland-western-hemisphere/.

- 65See Morgenthau, “Alliances in Theory and Practice,” in Arnold Wolters, Alliance Policy in the Cold War (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1959): 184–212; Stephen Walt, The Origins of Alliances (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1987).

- 66Tom O’Connor, “Exclusive: Cuba Warns US Pressure Drives Closer Ties With China and Russia,” Newsweek, September 27, 2024, https://www.newsweek.com/exclusive-cuba-warns-us-pressure-drives-closer-ties-china-russia-1959936.

- 67“The Opening of Cuba with Ambassador Jeffrey DeLaurentis,” Stimson Center, March 18, 2025, https://www.stimson.org/2025/the-opening-of-cuba-with-ambassador-jeffrey-delaurentis/.

- 68In June 2017, five months after assuming office, Trump reversed Obama’s Cuba policy via executive order. “Strengthening the Policy of the United States Toward Cuba,” White House, June 16, 2017, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2017/10/20/2017-22928/strengthening-the-policy-of-the-united-states-toward-cuba.

- 69National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1993, 102nd Congress, October 23, 1992, https://1997-2001.state.gov/www/regions/wha/cuba/democ_act_1992.html, 2575–2581.

- 70No U.S. president to date has been able to certify those conditions, and even if one did, Congress would have an opportunity to override the president’s determination. Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act of 1996, 104th Congress, March 12, 1996, https://www.congress.gov/104/statute/STATUTE-110/STATUTE-110-Pg785.pdf.

- 71President Bill Clinton loosened U.S. travel restrictions and remittance caps to Cuba during his second term less than two years after he signed the 1996 Helms-Burton Act. President Barack Obama embarked upon diplomatic normalization in 2015 and 2016 despite considerable opposition in Congress. And in 2024, President Joe Biden permitted Cuban entrepreneurs in the private sector to open a U.S. bank account. See, “Treasury Amends Regulations to Increase Support for the Cuban People and Independent Private Sector Entrepreneurs,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, May 28, 2024, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy2374.

- 72Manuel Orozco, “Remittances to Cuba and the Marketplace in 2024,” Inter-American Dialogue, March 2024, https://thedialogue.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Remittances-to-Cuba-and-the-Marketplace-in-2024-1.pdf, 7.

- 73Jim Wyss, “Western Union Halts Money Transfers to Cuba Citing New Sanctions,” Bloomberg, February 10, 2025, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-02-10/western-union-halts-money-transfers-to-cuba-citing-new-sanctions.

- 74John McIntire and Ricardo Herrero, “The Truth About Cuba’s Private Sector,” Americas Quarterly, July 12, 2024, https://americasquarterly.org/article/the-truth-about-cubas-private-sector/.

More on Western Hemisphere

February 3, 2026

By Peter Harris

January 30, 2026

By Peter Harris

January 28, 2026

Events on Western Hemisphere