How the U.S. should view NATO in 2021

As the NATO summit in Brussels begins, Defense Priorities fellow Daniel DePetris outlines the best approach to the alliance going forward—in particular how the U.S. role should change.

Read the backgrounder below.

NATO is a military alliance, where countries pledge to fight—and die—for one another

- NATO is a Cold War-era military alliance created for a specific purpose: to deny the USSR from dominating and organizing Europe, becoming a Eurasian hegemon, which could directly threaten the U.S.

- That logic—a U.S. security guarantee backed by large numbers of U.S. forces in Western Europe—made sense during intense competition between two nuclear superpowers. However, the strategic landscape has changed drastically since the Cold War ended 30 years ago.

- Russia is a limited threat to Europe, not a candidate, as the Soviet Union once was, to dominate the continent militarily. European NATO members are wealthy and capable enough to shoulder more of the burden for the continent’s defense than the U.S.

- Europeans should be encouraged to decide how much they want to defend themselves. But while the U.S. spends heavily to protect them, they can simply pass the buck to American taxpayers.

- Successive U.S. administrations have fostered European dependence on the U.S. They have pursued a strategy of suppressing joint European capability, lest it detract from the U.S. ability to call the shots in Europe via NATO. This strategy helps to deprive the U.S. of a strong partner that can act independently.

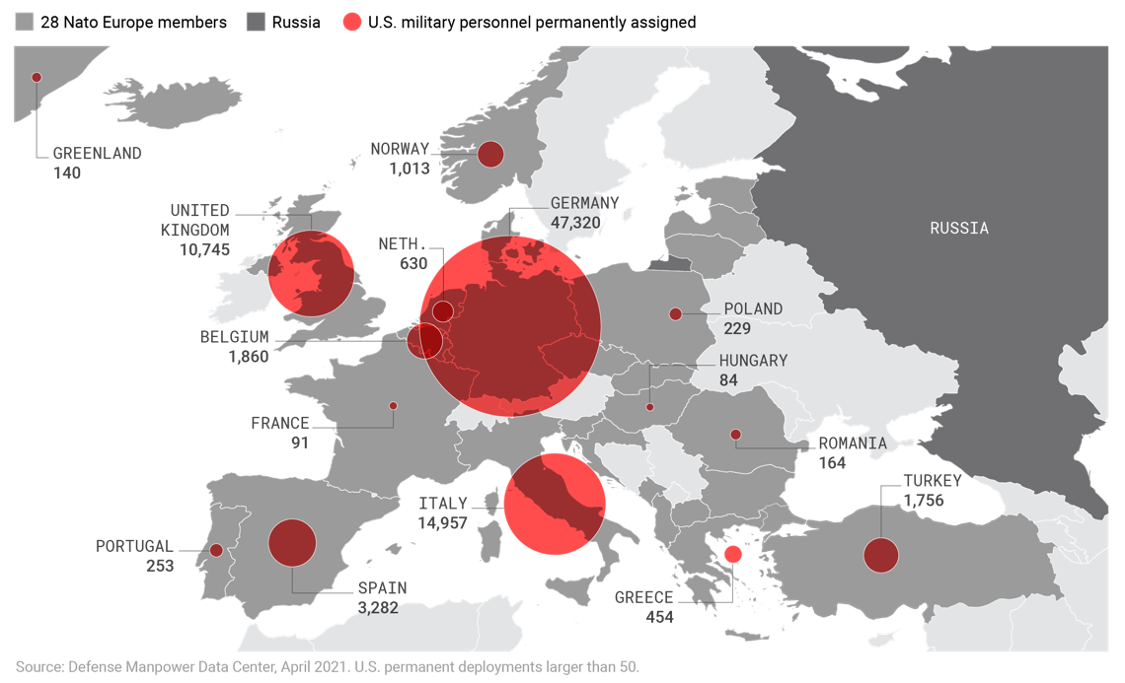

Permanent U.S. Military and DoD Personnel in Europe

\

Close the “open door”—end NATO enlargement

- Since 1999, NATO membership has nearly doubled to 30 members. Most recent additions are security dependents, rather than countries with capable, formidable militaries that can contribute to NATO’s military power.

- Montenegro and North Macedonia, NATO’s 29th and 30th members, with a combined force of some 9,000 active-duty troops, contribute nothing militarily substantive to the alliance. Montenegro has about half as many military service members as Washington D.C. has police officers.

- Adding more members has meant more territory for the alliance—especially the U.S.—to defend. And because NATO operates by consensus, expansion makes alliance decision-making harder.

- Expansion to Russia’s borders exacerbates Russian belligerence and damages U.S-Russia diplomacy. NATO expansion does not excuse Russian actions against NATO states, like cyber espionage and election meddling, but it does help explain them.

- Despite Ukraine and Georgia’s desire to enter NATO, the U.S. should refuse their membership. Ukraine and Georgia have territorial conflicts with Russia and Russian forces within their borders—allowing them into NATO would place the U.S. on a collision course with nuclear superpower Russia.

- The U.S. should dispel any notion Ukraine or Georgia could ever join. Even suggesting possible NATO membership provides aspiring members with a false sense of hope and distorts decisions required to bring policies in line with their circumstances as relatively weak states bordering Russia.

Europe should take primary responsibility for checking Russia

- European states can bear the main burden of maintaining a stable balance of power, the primary U.S. national security objective in Europe.

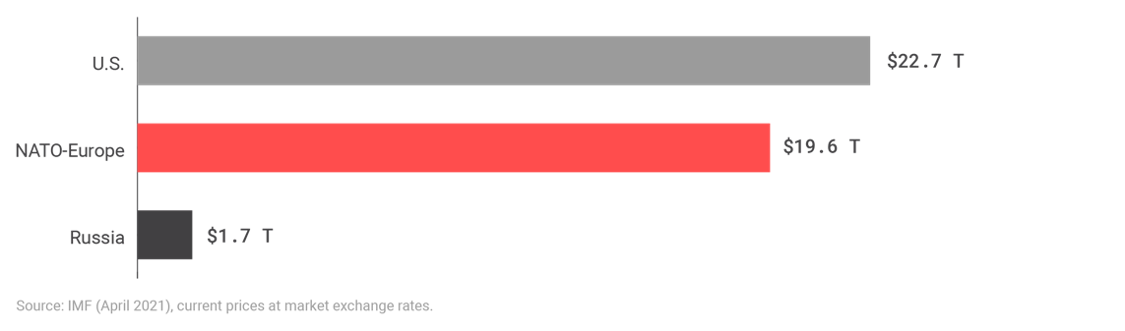

- Europe’s GDP is comparable to the U.S., yet the U.S. alone accounts for nearly 70 percent of NATO’s total military spending—more than twice what the other 29 members spend combined.

- The outsized U.S. commitment to Europe produces “free-riding,” where European states are disincentivized from making the investments necessary to field modern, functional militaries.

- U.S. overcommitment also encourages “reckless driving,” where states assured of superpower backing act more aggressively than they otherwise would. This means allied behavior can drag the U.S. into conflict where it has no vital interests at stake.

- Continuing to draw down U.S. troops in Europe could encourage European governments to invest more in their militaries to deter Russia and decrease incentives for reckless driving.

- Because Europe is so safe, even a substantially reduced U.S. presence might not prompt greater European military investments. Even such a scenario benefits the U.S., which will have saved money, reduced risks, and created space for better relations with European nations and Russia.

- A much smaller U.S. presence in Europe is not just about cutting costs for the U.S.—although that is important—but also about husbanding limited U.S. resources.

- Fewer land forces in Europe could lead to a shift of defense spending, at least in a relative sense, toward more naval and air forces. Or savings could simply be diverted to more pressing priorities at home.

NATO-Europe’s Economic Power is Near that of the U.S. and dwarfs Russia’s

European strategic autonomy should be encouraged

- Europe is moving haltingly toward “strategic autonomy.” France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the Netherlands have each supported the concept of European countries coordinating more to facilitate their defense without U.S. oversight.

- Support is being followed by tentative action. Germany and France have begun collaborating on joint weapons projects, including a next-generation fighter jet.

- NATO has kept Europe beholden to U.S. oversight, which some incorrectly view as beneficial. Opposing European autonomy in defense leaves the U.S. without powerful allies to reduce its own burdens. This matters more as power shifts to Asia.

- Although the limits of the Russian threat and operational shortcomings, like poor interoperability, challenge European strategic autonomy, the U.S. should aid it by giving it a fulsome endorsement and reducing its forces on the continent.

Out-of-area operations distract from NATO’s core mission

- Pressing NATO allies to focus on China would be a mistake, distracting the alliance from its core purpose: defending Europe.

- The U.S. is best positioned to compete with China by a Europe that defends itself, freeing up U.S. resources for higher priorities.

- The U.S. and Europe have different threat perceptions vis-à-vis China. Europe itself is divided on managing China’s rise, which poses a direct challenge to countries in Asia more than Europe.

- Even countries increasingly wary of China’s actions, like Germany, are disinclined to follow the U.S. into a cold war against China.

- China is the European Union’s second largest trading partner, with trade in goods alone worth more than $700 billion annually. Europe will be reluctant to jeopardize this relationship by antagonizing China, unless its core interests are in conflict.

- Pushing European allies to send a frigate or two to East Asia, as Germany recently has, or drafting strategies for dealing with China, like the U.K., is more about making NATO relevant to the U.S. than meaningfully challenging China.

- European states should focus their limited defense spending on Europe—on maintaining the ability to defeat Russia in a conventional war.

- A Europe that can effectively defend itself decreases U.S. security burdens and frees up limited resources for higher priorities at home and in East Asia.

More on Europe

op-edNATO, Alliances, Europe and Eurasia

July 2, 2025

Featuring Jennifer Kavanagh

June 24, 2025

op-edGrand strategy, Diplomacy, Europe and Eurasia

June 16, 2025

Events on NATO

virtualNATO, Alliances, Deterrence, Europe and Eurasia, Nuclear weapons

July 2, 2024