Presidents Trump and Biden share the same regime change strategy

- After Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez’s death in 2013, then-Vice President Nicolás Maduro succeeded the late socialist leader, consolidating power amid rampant economic mismanagement and increasing violence and deprivation.

- Venezuela’s authoritarian slide accelerated under Maduro’s rule. Electoral fraud, crackdowns on opposition figures, and human rights abuses hardened U.S. resolve to apply pressure to change Caracas’ policies.

- President Trump reportedly discussed using U.S. military force to oust Maduro in 2019 but pursued non-military regime change instead, increasing economic and diplomatic pressure in the false hope the Venezuelan leader would vacate his office.

- President Biden has continued this policy. The U.S. objective remains: (1) to delegitimize and push out Maduro as the country’s leader and (2) put pressure on Venezuela’s economy to force Caracas into reinstituting democracy.

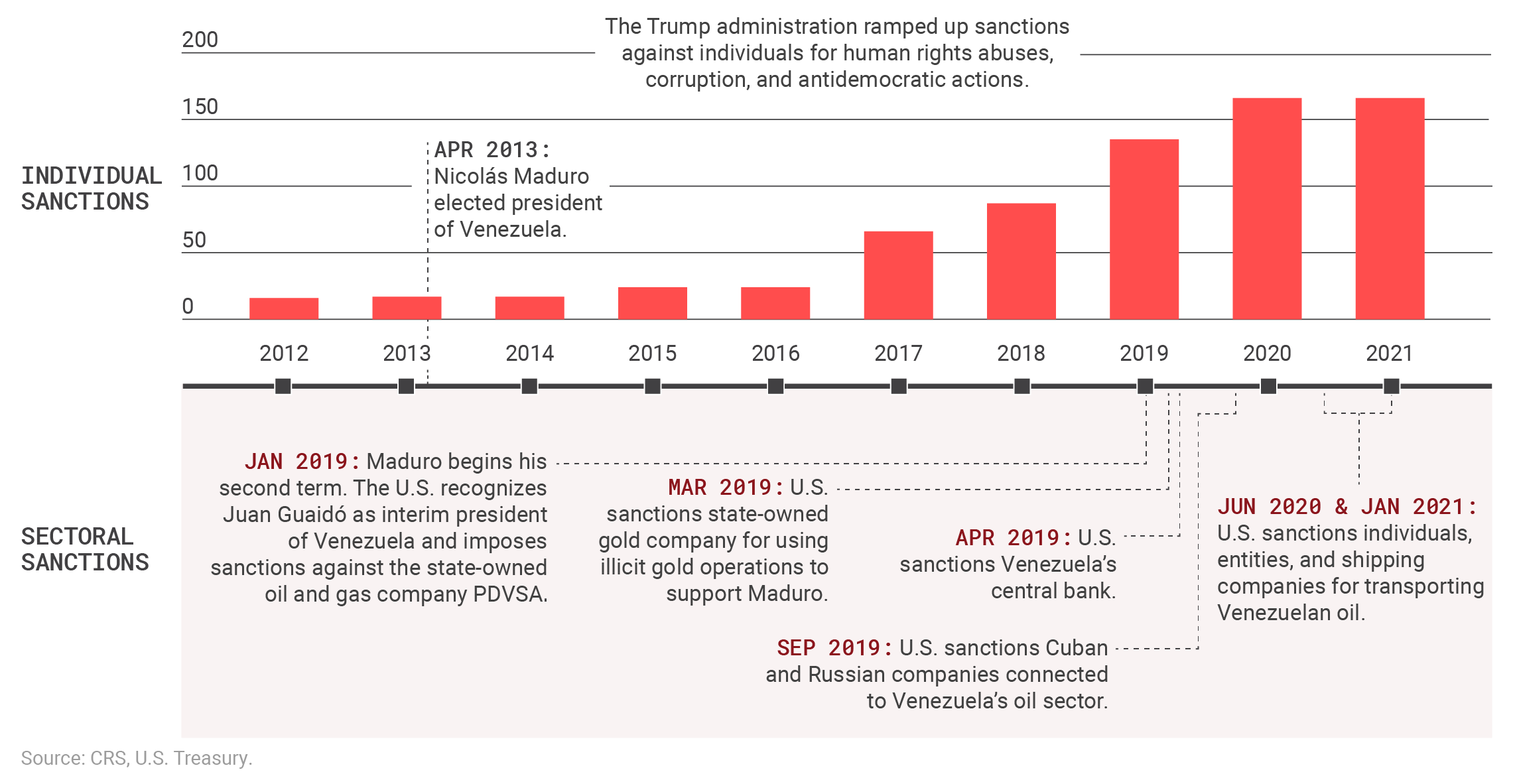

Timeline of recent U.S. sanctions on Venezuela

In recent years, the U.S. added both individual sanctions against Venezuelans and Venezuelan-connected individuals and broader sectoral sanctions on key industries in Venezuela’s economy.

Regime change via “maximum pressure” sanctions has failed

- Robust economic sanctions against Venezuela’s oil and gold industries remain in place, and the U.S. denies Maduro’s political legitimacy.

- This strategy has failed: Maduro’s political position has withstood U.S. pressure. Russia, China, Cuba, and, most important, the Venezuelan military maintain their support for Maduro. The anti-Maduro opposition is weak and divided.

- Venezuela’s political stalemate is a humanitarian concern unrelated to U.S. security. While Maduro is a brutal dictator, regime change is unlikely to work, exacerbates humanitarian suffering, and assumes Venezuela’s problems are America’s.

- U.S. policy sabotaged intra-Venezuelan negotiations.[1On the same day the U.S. froze Venezuelan government assets in U.S. jurisdiction in 2019, national security adviser John Bolton declared to the Lima Group that the time for diplomacy with the Maduro government had run out. Two days later, Maduro suspended negotiations with the opposition. See Anatoly Kurmanaev, “Venezuela’s Leader Suspends Talks With Opposition,” New York Times, August, 8, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/08/world/americas/venezuela-maduro-opposition-talks-barbados.html. Thwarting diplomacy between the Maduro government and the opposition needlessly prolongs a humanitarian crisis for no conceivable gain. The U.S. should abandon regime change and unwind sanctions related to that goal.

The pitfalls of U.S. “maximum pressure” on Venezuela

- Sanctions worsened Venezuela’s humanitarian disaster, depriving Caracas of revenue to finance basic imports. Venezuelan government property under U.S. jurisdiction is blocked, and entities that buy or transport Venezuelan oil (the country’s main source of revenue) are vulnerable to U.S. sanctions.

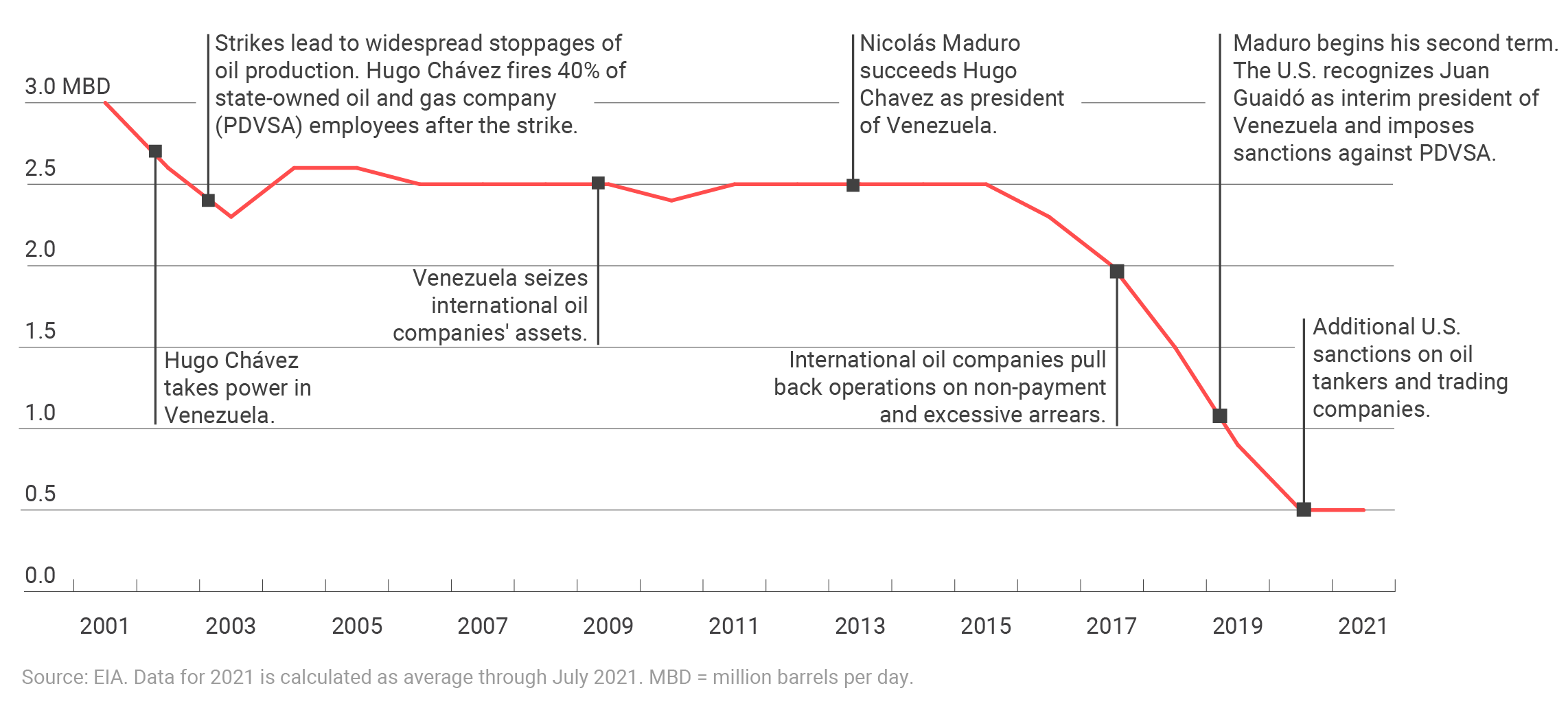

- The U.S. imposed sanctions after Maduro’s 2013 election victory and secondary sanctions on Venezuelan oil by early 2019. Crude oil production plummeted from 2 million BPD in 2017 to 630,000 BPD in 2020. Crude oil exports, 99 percent of Venezuela’s export earnings, plunged to a 77-year low last year.

- The U.S. designated more than 400 Venezuelan entities for sanctions since 2009, contributing to decreased output and revenue from Venezuela’s oil industry and hampering access to loans from international financial institutions (e.g., World Bank and IMF).

- U.S. sanctions hit Venezuelans hardest, exacerbating shortages of scarce items: medicine, fuel, Covid-19 vaccines, and other humanitarian goods. Fearful of large fines, financial institutions hesitate to process lawful humanitarian transactions.

- U.S. prohibitions on diesel swaps (in which oil is bartered for gasoline) compound dire gas shortages in Venezuela. Lack of fuel cripples the transportation of food supplies when 96 percent of the population already lives in poverty.

- U.S. policies immiserate Venezuelans by design but have not translated into Maduro’s overthrow or hastened a return to democracy. Maduro firmly holds power with no sign of relinquishing control.

Venezuela’s oil production

Reasons for the sharp fall in Venezuela’s oil production include corruption and mismanagement in the nationalized industry, the poor states of PDVSA’s finances and infrastructure, and U.S. sanctions.

Do not treat Venezuela’s problems as U.S. problems

- Minimizing Venezuela’s humanitarian crisis—or at least not making it worse—reduces migration flows from there to the U.S.

- The U.S. cannot solve Venezuela’s domestic problems. Even if it could, because the U.S. no longer recognizes Maduro’s government and devoted years to seeking its ouster, Caracas views U.S. proposals skeptically.

- Rather than try to change Venezuela’s government, the U.S. should allow those with a greater stake in the outcome—the OAS, Mexico, and neighboring Colombia—to facilitate intra-Venezuelan talks.

- The U.S. should support ongoing intra-Venezuelan talks in Mexico (currently suspended over the extradition of Alex Saab, a Colombian businessman and Maduro associate), using its influence over the Venezuelan opposition to increase the chances of a compromise.

- If talks resume, then the U.S. should encourage the opposition to drop the removal of Maduro or the dissolution of his government as a precondition to signing an agreement, which is unrealistic given the strength of Maduro’s position.

- Like the E.U., the U.S. should stop recognizing Juan Guaidó as the legitimate representative of the Venezuelan people. Guaidó was not elected president, controls no state apparatus in Venezuela, depends on foreign support (limiting his effectiveness), and lacks popular support among Venezuelans.

- The U.S. should relax most sectoral sanctions implemented since early 2019, in particular those on oil and natural gas production and export, which have failed at regime change and hurt many Venezuelans.

- The U.S. could permit Venezuela to access limited financial reserves locked in U.S. accounts for the purpose of financing imports of medicine, food, and other humanitarian items that alleviate Venezuelan suffering.

- To prevent a scenario in which financial institutions avoid permitted transactions for fear of violating U.S. sanctions—known as “overcompliance”—the U.S. Treasury Department should publish unequivocal guidance that allows Venezuela-related payments tied to humanitarian and medical items.

Endnotes

- 1On the same day the U.S. froze Venezuelan government assets in U.S. jurisdiction in 2019, national security adviser John Bolton declared to the Lima Group that the time for diplomacy with the Maduro government had run out. Two days later, Maduro suspended negotiations with the opposition. See Anatoly Kurmanaev, “Venezuela’s Leader Suspends Talks With Opposition,” New York Times, August, 8, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/08/world/americas/venezuela-maduro-opposition-talks-barbados.html.

More on Western Hemisphere

In the mediaGlobal posture, Europe and Eurasia, Grand strategy

Featuring Jennifer Kavanagh

January 20, 2026

op-edEurope and Eurasia, NATO

January 20, 2026

Events on Venezuela

virtualVenezuela, Western Hemisphere

October 28, 2025