August 16, 2019

U.S. military withdrawal from Afghanistan—with or without an agreement

Key points

- Following 9/11, the United States was right to go to war in Afghanistan. Targeting Al-Qaeda and the Taliban government which harbored them following the 9/11 attacks was a sensible and achievable mission.

- After a swift victory and the establishment of a new, popular Afghan government, policymakers should have removed U.S. troops.

- Instead, Washington pursued a nation-building effort to establish a central authority to govern all of Afghanistan—a goal impossible to achieve at reasonable cost and unrelated to the core security interests that justified the initial campaign.

- After nearly 18 years of war and our key goals accomplished long ago, it is past time to withdraw all U.S. forces to focus on vital national security interests.

Current state of play

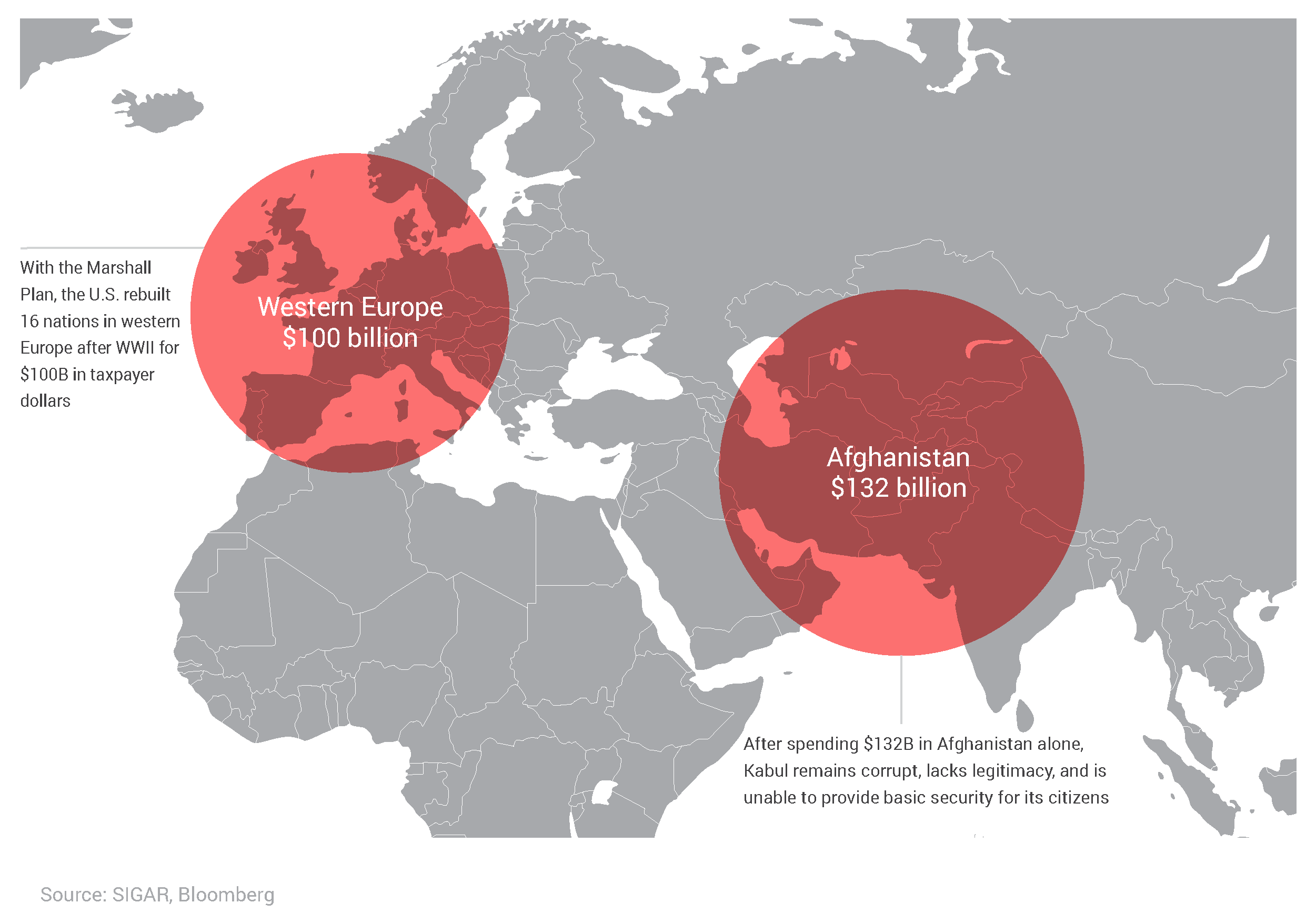

In August 2017, President Trump announced a small “Afghan surge” that increased the U.S. force in Afghanistan to 14,000 troops. Despite the reinforcement and the creation of dedicated U.S. Army advisor brigades, Afghan government forces continue to lose ground. The United States has spent more on Afghan reconstruction and security force assistance than it did on the Marshall Plan following WWII—but it has precious little to show for it.

The war against the Taliban is being lost by the U.S.-trained, -equipped, and (largely) -funded Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF). In January, Afghan President Ashraf Ghani said that ANSF units had lost more than 45,000 soldiers and policemen since late 2014. Even the new head of United States Central Command, Marine General Kenneth McKenzie Jr., conceded that ANSF casualty levels are unsustainable. There is scant evidence that the ANSF can win this war despite almost two decades of U.S. military and financial support. The Taliban now control more territory than at any point since 2001.

In September of 2018, the president appointed Zalmay Khalilzad as the U.S. Special Representative to negotiate the withdrawal of U.S. forces with the Taliban. As negotiations have progressed, the U.S. has gradually scaled down its deployed troops. The latest withdrawal, coming on the heels of apparent progress in negotiations, was announced on August 1, 2019, and would leave between 8,000 and 9,000 troops in country.

The agreement currently being negotiated, which both sides have agreed to in principle, rests on four pillars:

- The Taliban agree to renounce Al-Qaeda and all terrorists

- A cease-fire covering all parties

- The Taliban agree to negotiate with the Afghan government

- U.S. military withdrawal

While the ongoing negotiations have often been referred to as “peace talks”—and the agreement alludes to a draw down—complete U.S. military withdrawal should be the objective.

Peace is unlikely given the fragmented nature of Afghan society and the balance of power among rival factions, and more important, cannot be enforced by the U.S. either before or after its exit. A withdrawal of forces, however, is entirely within the power of the U.S. government, and in line with U.S. interests, which do not require a residual presence in Afghanistan.

If the final agreement makes withdrawal contingent on the other three conditions being met, it is a recipe for a permanent U.S. presence in Afghanistan. The Taliban are untrustworthy, and any agreement is non-enforceable after a U.S. exit anyway. What safeguards U.S. interests is deterrence by punishment: the ability to strike the Taliban should they facilitate harm to the United States, regardless of the state of the Afghan government and security forces post-withdrawal.

Assessing the four pillars of the agreement

1. The Taliban agree to renounce Al-Qaeda and all terrorists

The Taliban are a nationalist movement with local aims—they pose no threat beyond Afghanistan’s borders. The U.S. goal for negotiations with the Taliban is to extract a commitment to renounce Al-Qaeda and a pledge that Afghanistan will never host international terrorists of any stripe. However, a formal Taliban commitment is ultimately unnecessary because of deterrence. Therefore, a military withdrawal should not be conditioned on securing one.

The red line already established by the U.S. is crystal clear: Any attack on U.S. citizens planned or organized in Afghan territory will result in an immediate and overwhelming U.S. military response, up to and including another punitive expedition with a ground force element, if necessary.

It is this threat and its credibility—deterrence by punishment, not negotiated promises—that discourages the Taliban from ever again supporting transnational jihadist terrorism.

Despite Washington’s failed nation building (counterinsurgency) campaign, the Taliban are under no illusions about the ability of the United States to successfully project combat power—to “kill people and break things.” Even as early as October 2001, some elements of the Taliban were willing to discuss handing Osama bin Laden over to a third party in exchange for a cease fire. Having now endured 17 years on the run, perhaps 60,000 fighters killed, and the repeated attrition of its senior leaders, the Taliban understand just what the United States can and will do to any future Islamic Emirate that permits attacks on Americans. Though there are few outside some corners of Washington who think the United States, or any outside power, can build states, the conventional deterrent capability of the U.S. military remains unmatched.

The specter of the Islamic State’s Afghan offshoot, the Islamic State—Khorasan Province (ISIS-K), is erroneously being used by some as a pretext for indefinitely delaying U.S. withdrawal.

ISIS-K is a limited, regional actor in small pockets within Afghanistan. Though skilled at conducting horrific bombing attacks inside Kabul’s security “ring of steel,” ISIS-K is only able to take refuge in a limited amount of territory in Afghanistan’s remote Nangarhar and Kunar provinces. The U.S. military and intelligence communities remain divided over assessments of ISIS-K’s strength and international reach, with U.S. intelligence agencies less concerned about the group.

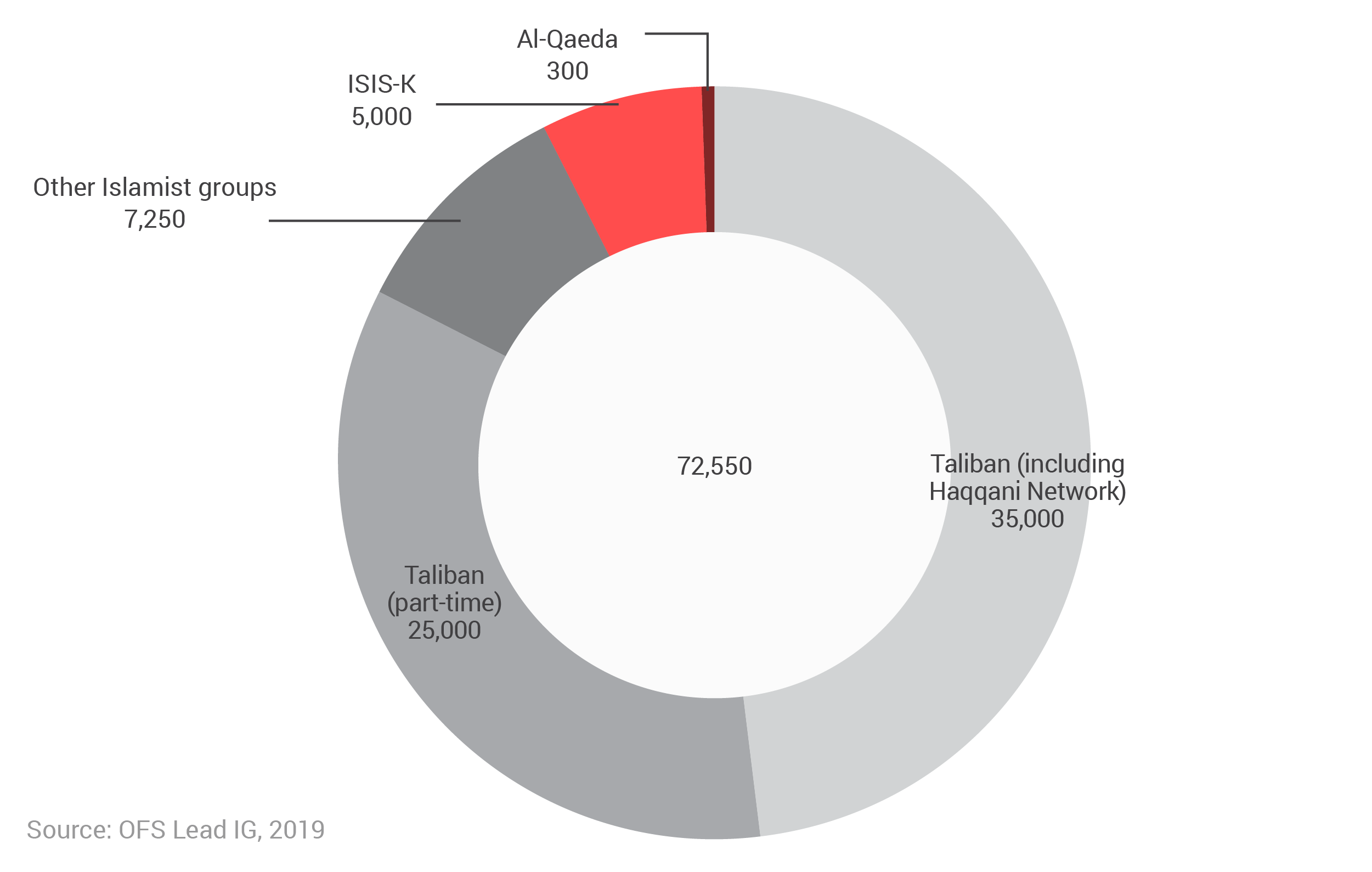

Highest estimates of insurgent forces in Afghanistan

Unlike Al-Qaeda and arguably ISIS-K, the Taliban have local aims. Once U.S. forces leave Afghanistan, the Taliban, deterred by U.S. power from harboring terrorists, will not provide safe haven to Al-Qaeda and are likely to turn their attention toward defeating ISIS-K.

ISIS-K fighters number at most 5,000—a fraction of the estimated size of the Taliban’s total force. The Taliban remain a dedicated enemy of ISIS-K and would extinguish this more fanatical offshoot once their forces are no longer tied down fighting the U.S.—but this will happen only once U.S. forces leave, and certainly not because of any piece of paper they agree to sign. A limited ISIS offensive into Jowzjan Province in 2018 was repelled by the Taliban, an example of the enmity between the two groups.

Furthermore, keeping U.S. troops in Afghanistan to combat ISIS-K is likely to backfire. The Taliban’s chief grievance and rallying cry is the presence of foreign troops on Afghan soil. Should the Taliban somehow be induced to accept a limited U.S. military presence in order to combat ISIS-K, they are likely to see fighters defect to their rivals as a result of Taliban hypocrisy. Thus, even a limited U.S. presence is likely to perpetuate, if not worsen, the problem.

2. A cease-fire covering all parties

Afghan security is not the same as U.S. security. An enduring cease-fire is a “nice-to-have,” not essential for a U.S. withdrawal.

Afghanistan has been in a state of civil war for decades—before and during the U.S. military presence—and will likely continue in a state of upheaval for some time. With many factions competing for influence locally and nationally, even a desire for peace among the key Taliban leadership cannot prevent continued hostilities.

The U.S. should expect—and accept—an uptick in violence upon withdrawal, as the different Afghan political factions struggle to settle the future of their country. The Taliban are in a strong position and are unlikely to permanently settle with a government they feel they can defeat on the battlefield. This is not a barrier to U.S. withdrawal, however. The U.S. and NATO successfully withdrew far larger forces throughout fighting from 2012–2014. The logistics of a withdrawal during ongoing operations now will be far simpler and should be carried out regardless of the state of in-country hostilities.

3. The Taliban agree to negotiate with the Afghan government

Taliban negotiations with the Afghan government could potentially result in an enduring power-sharing agreement, but expectations of a permanent political settlement between the two warring factions are unrealistic. The Taliban know they have a strong hand and are unlikely to grant legitimacy to what they view as a collaborationist government. However, ending an ongoing Afghan civil war is not a vital U.S. interest, and its resolution should not be a precondition of withdrawal.

The U.S. lacks the ability to end the Afghan civil war, having been unable to defeat the Taliban even when 100,000 U.S. troops were deployed to Afghanistan. The enduring fragmentation of Afghan society may affect its neighbors, but it will not affect Americans thousands of miles away.

4. U.S. military withdrawal

The agreement calls for a draw down in U.S. forces. However, the priority should be a complete U.S. military withdrawal within 12–18 months.

This timeframe is long enough to mitigate some of the inevitable negative consequences of a U.S. withdrawal while short enough to prevent further delays and attempts at bureaucratic log rolling. “Complete” means the withdrawal of all U.S. military personnel from the country, excepting the standard embassy complement. Exceptions for special operations personnel and military advisors should not be granted, as they would provide justification for a substantial perpetual presence.

Intelligence agents, Afghan commandos, and drones flown from neighboring countries will remain as important counterterrorism tools. The biggest counterterrorism stick, again, remains deterrence: the threat of renewed U.S. attack on the Taliban or other Afghan sponsors of terrorism.

U.S. military withdrawal is all that matters, and it doesn’t require any negotiations

The future of Afghanistan is unknowable. In the absence of U.S. forces, the Taliban are highly unlikely to be defeated, but the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) may hold together. Afghanistan’s neighbors, all of whom have a greater stake in the outcome there than the United States does, may individually or collectively ensure the Taliban do not substantially improve their position. And Afghans are sick of war: Both Taliban defections and grassroots peacemaking efforts indicate a bloody end to the Afghan civil war is not a forgone conclusion, even if chances of a peaceful future are slim.

In the worst-case scenario, the Taliban may triumph in the Afghan civil war, perhaps quickly. Such an outcome will have regional ramifications but does not jeopardize American security. We don’t need a pro-U.S. government in Afghanistan—just one that isn’t actively plotting against us. Indeed, a Taliban state may be more easily deterred by American power than a Taliban insurgency.

Should the civil war continue, or even end with a Taliban triumph, Americans will remain safe because of geography; U.S. global intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, and strike (ISR-Strike) capabilities; and the U.S. military’s unmatched conventional deterrent capabilities. Afghanistan’s internal political outcome is beyond the ability of the United States to direct.

As George F. Kennan, one of America’s greatest diplomats, noted, “There is more respect to be won in the opinion of this world by a resolute and courageous liquidation of unsound positions than by the most stubborn pursuit of extravagant or unpromising objectives.” Policymakers should heed his advice and implement a full withdrawal before the United States’ reputation and more American lives are sacrificed for Afghan politics rather than U.S. security.

More on Asia

By Jennifer Kavanagh and Dan Caldwell

July 9, 2025

Featuring Jennifer Kavanagh and Dan Caldwell

July 9, 2025

Featuring Lyle Goldstein

July 4, 2025