Key points

- Afghanistan was not Korea. False analogies to peacetime military garrisons cheapen war and conflate wildly different forms of “support” to U.S. allies.

- War in Afghanistan was costly—to taxpayers, to civilians, to American soft power, to democratic legitimacy, and to the West’s strategic attention. Thus, withdrawal saved a fortune, saved lives, aided America’s reputation, honored democratic and constitutional principles, and focused Western strategists.

- War was not protecting Americans from terrorism. Keeping troops in but one of many places terrorists may operate did not meaningfully reduce Americans’ microscopic risk of being harmed in a terrorist attack.

- War was not helping Afghanistan. Democracy is a strong word for what U.S. forces propped up. Far from maintaining stability, the continued presence of those forces only prolonged armed struggle against a corrupt rentier state, impeding organic or sustainable long-term development.

- Credibility is highly contextual and unaffected by admitting defeat after 20 years of futile effort. If anything, the resources freed up by withdrawal make the United States better able to honor other commitments.

Afghanistan was not Korea

The defining decision of President Joe Biden’s first year of foreign policy was the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan, where America fought its longest war from 2001 to 2021.

By the end of this time, the costs of continued war outweighed any strategic or humanitarian interest the United States had left in the country. This explainer accounts for these costs then compares them to the war’s alleged benefits to show why withdrawing from Afghanistan was necessary, beneficial, and overdue.

Amid heartbreaking scenes at Kabul airport, several prominent critics argued the United States should have sustained a “light footprint” to “support American allies,” just as it does all over the world.1Rory Stewart, “America Was Finally Using Biden’s Afghanistan Strategy. Then He Pulled the Plug,” Washington Post, August 16, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2021/08/16/afghanistan-biden-withdrawal-military/. After all, U.S. forces have been in Germany, Japan, and South Korea for more than 70 years.2Rory Stewart, “Failure, and the Villains of the Western Campaign in Afghanistan,” August 19, 2021, in Western Way of War, produced by RUSI, podcast, 22:30, https://rusi.org/podcasts/western-way-of-war/episode-60-rory-stewart-failure-and-villains-western-campaign-afghanistan. Should the United States have been equally patient in Afghanistan?3Max Boot, “Twenty Years of Afghanistan Mistakes, but This Preventable Disaster Is on Biden,” Washington Post, August 15, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2021/08/15/twenty-years-afghanistan-mistakes-this-preventable-disaster-is-biden/.

No. The United States was fighting a war in Afghanistan, one utterly incomparable to its peacetime presence elsewhere. No other allies receive America’s direct participation in a civil war of such scale, duration, and intensity, and for good reason: war costs more than peace in ways that affect the wisdom and ethics of indefinitely waging it.

Euphemisms like “presence” or “support” omit description of just what the United States was doing in Afghanistan. In recent years, it was predominantly air support—which is military-speak for dropping bombs and firing missiles to kill people and blow up stuff. In 2018 and 2019, U.S. forces dropped 7,362 and 7,423 munitions a year, respectively—about 20 per day—compared to just 957 bombs in 2015. Fighting from the air instead of the ground reduced risk to U.S. servicemembers, but it did not make U.S. involvement any less warlike.4Neta C. Crawford, “Afghanistan’s Rising Civilian Death Toll Due to Airstrikes, 2017–2020,” Brown University Costs of War Project, December 7, 2020, https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/files/cow/imce/papers/2020/Rising%20Civilian%20Death%20Toll%20in%20Afghanistan_Costs%20of%20War_Dec%207%202020.pdf.

Moreover, the speed of the Taliban victory after U.S. withdrawal demonstrates the United States was not merely fighting a war but preserving a state of war that would not have otherwise persisted. That’s a fundamentally different model than postwar Germany, Japan, or South Korea, in which the U.S. achieved victory, then stayed to deter external threats, quickly enabling decades of peace. Conflating these missions trivializes the substantial costs of indefinite meddling in intractable foreign conflicts.

The costs of war were many—so withdrawal saved a lot

Withdrawal saved a fortune

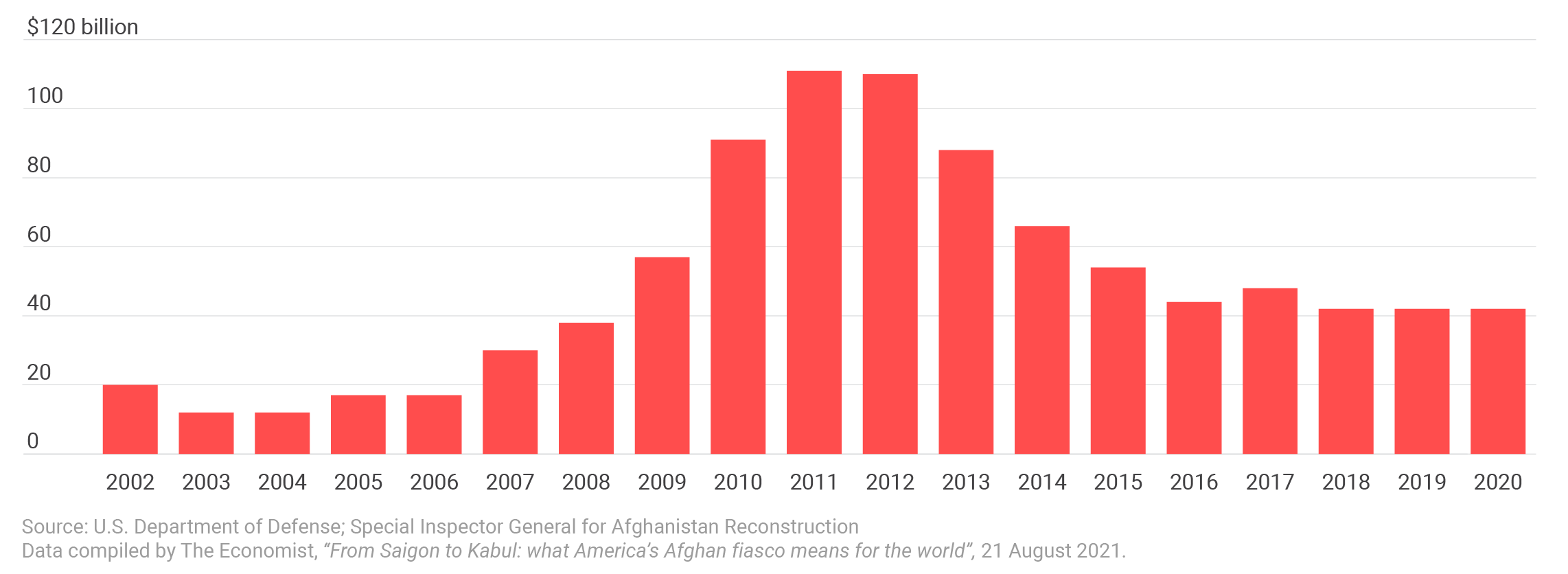

From 2016 to 2019, the war in Afghanistan cost some $40 billion a year to support between 9,000 and 13,000 troops in the country. By comparison, maintaining U.S. troops in South Korea and Japan cost just $3 billion and $5 billion a year over this same period—even though these countries housed 28,500 and 55,000 troops, respectively.5Hyonhee Shin and Joyce Lee, “Factbox: U.S. and South Korea’s Security Arrangement, Cost of Troops,” Reuters, March 7, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-southkorea-usa-alliance/factbox-u-s-and-south-koreas-security-arrangement-cost-of-troops-idUSKBN2AZ0S0.

Any presence in Afghanistan beyond 2021 would again have cost taxpayers much more than peacetime garrisons elsewhere. Although President Trump reduced troop levels to 2,500 following the 2020 Doha agreement, this lighter footprint was only possible because of the agreement to withdraw. Had President Biden chosen to stay, such levels would not have sufficed moving forward. A United States Institute of Peace Afghanistan study group concluded in February 2021 that “around 4,500 troops are required to secure U.S. interests under current conditions”—and conditions were likely to change for the worse once the Taliban launched their summer offensive.6Afghanistan Study Group, “Afghanistan Study Group Final Report,” U.S. Institute of Peace, February 3, 2021, https://www.usip.org/publications/2021/02/afghanistan-study-group-final-report-pathway-peace-afghanistan. Besides, the number of troops in the country was not the primary driver of increased costs, as the East Asian comparisons show.

U.S. spending on the war in Afghanistan

Fighting the war in Afghanistan was significantly more costly than maintaining permanent peacetime garrisons in either Japan or South Korea.

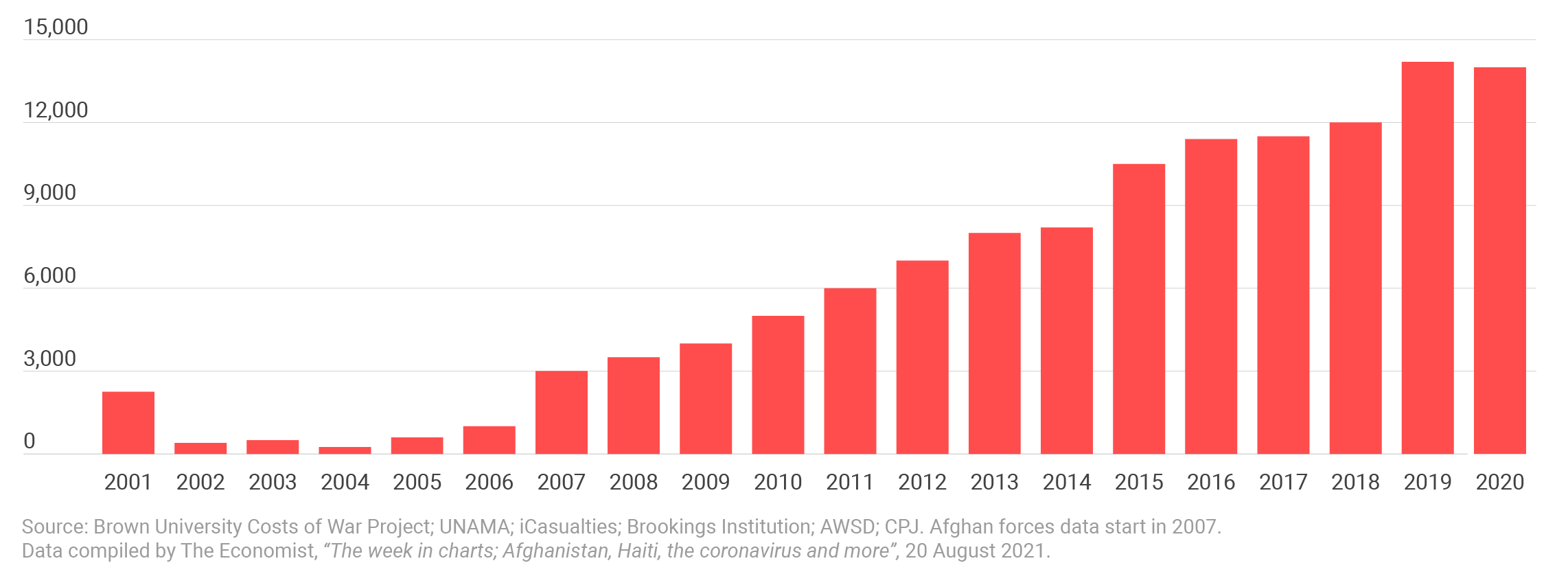

Withdrawal saved lives

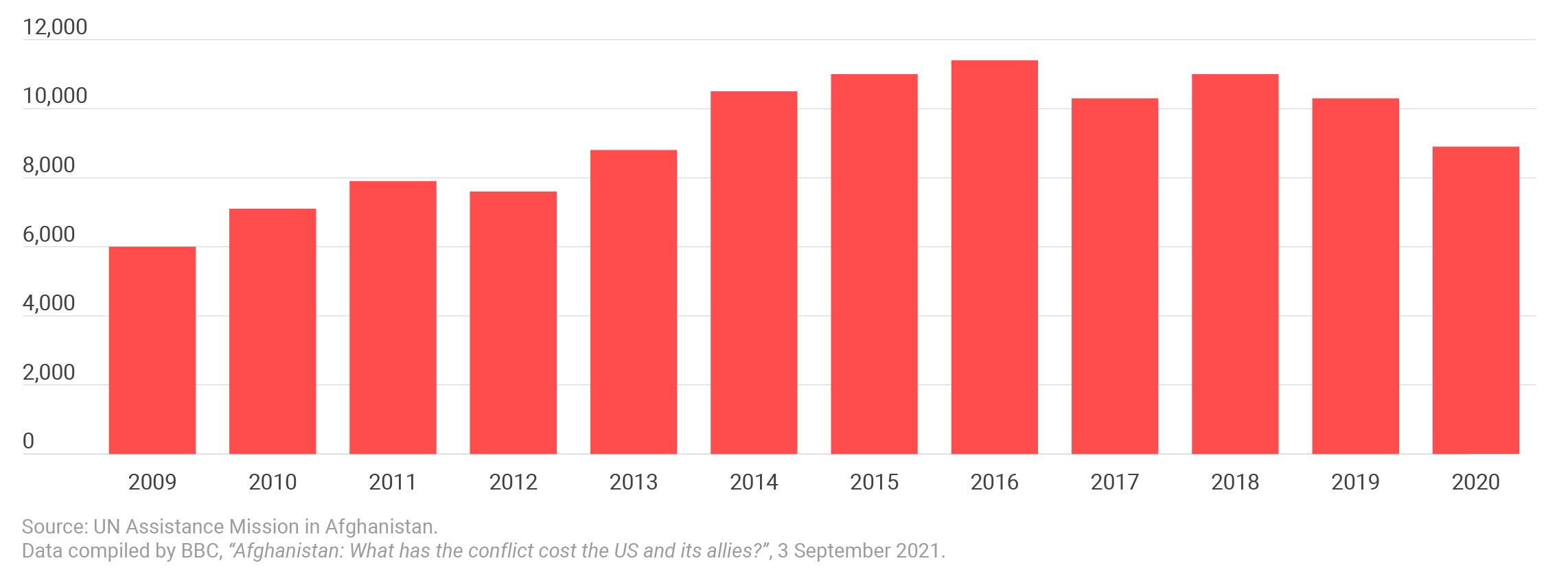

From 2001 to 2021, the war in Afghanistan killed roughly 240,000 people, and more than 71,000 civilians.7“Afghan Civilians,” Brown University Costs of War Project, accessed October 8th, 2021, page updated as of April 2021, https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/costs/human/civilians/afghan. And unlike American fatalities, overall fatalities had markedly increased since 2015, approaching 15,000 Afghan soldiers and civilians each year.8“The Week in Charts: Afghanistan, Haiti, the Coronavirus and More,” August 20, 2021, The Economist, https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2021/08/20/the-week-in-charts-afghanistan-haiti-the-coronavirus-and-more. Focusing only on American casualties inverted the reality on ground, which was trending towards more death rather than less.

For perspective, more civilians were dying from combat each year than Americans who perished on 9/11. This made continued U.S. presence difficult to justify on counterterrorism grounds. Likewise, any humanitarian case for remaining in Afghanistan had to overcome terrible loss of life among those it intended to help.

Civilian casualties in Afghanistan

The war in Afghanistan injured or killed thousands of civilians each year, meaning any humanitarian case for staying in Afghanistan cannot overlook how deadly the war was to civilians on the ground.

Withdrawal safeguarded America’s reputation and ended a cycle of violence

However noble America’s intentions, most of the world did not see U.S. bombing as benevolent. The Eurasia Group Foundation’s annual survey of how foreign publics perceive the United States found “[d]isapproval of America’s continuation of the war in Afghanistan was a significant driver of anti-American sentiment” in early 2021.9Mark Hannah and Caroline Gray, “Democracy in Disarray: How the World Sees the U.S. and Its Example,” Eurasia Group Foundation, May 2021, https://egfound.org/2021/05/modeling-democracy-democracy-in-disarray/#full-report. This was especially so in Muslim-majority nations, which largely perceived the United States as an imperialist aggressor.10Global Indicators Database, “Opinion of the U.S.,” Pew Research Center, updated March 2020, https://www.pewresearch.org/global/database/indicator/1/; Luke Baker, “Research Explores What 1.3 Billion Muslims Think,” Reuters, April 7, 2008, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-religion-islam-book/research-explores-what-1-3-billion-muslims-think-idUSL0768852020080407. Airstrikes do not seem a “light footprint” to those living beneath their predation.11Anand Gopal, “The Other Afghan Women,” New Yorker, September 6, 2021, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/09/13/the-other-afghan-women; International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clinic at Stanford Law School and Global Justice Clinic at NYU School of Law, “Living Under Drones: Death, Injury and Trauma to Civilians from US Drone Practices in Pakistan,” 2012, https://www-cdn.law.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Stanford-NYU-Living-Under-Drones.pdf; Christopher J. Coyne and Abigail R. Hall, “The Drone Paradox: Fighting Terrorism with Mechanized Terror,” The Independent Review 23, no. 1 (2018): 51–67. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26591799.

This negative perception hampered American efforts in the broader war on terror, where anecdotes abound of airstrikes driving terrorist recruitment.12Audrey Kurth Cronin, “Why Drones Fail,” Foreign Affairs, July/August 2013, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/somalia/2013-06-11/why-drones-fail. Retired Gen. Stanley McChrystal once warned drones were “hated on a visceral level,” and worried this hatred exacerbates a “perception of American arrogance.”13David Alexander, “Retired General Cautions Against Overuse of ‘Hated’ Drones,” Reuters, January 7, 2013, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-afghanistan-mcchrystal-idUSBRE90608O20130107. Hatred and resentment fueled enemy propaganda and undercut America’s ability to call out rival regimes for their own human rights abuses. At a minimum, prolonging war in Afghanistan would have deepened a widespread belief that the United States meddles too much and kills too many policing faraway conflicts.14“Future Foreign Policy: Global perceptions of the U.S.,” Webinar from Atlantic Council with Caroline Gray, Washington, DC, June 16, 2021, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/event/future-foreign-policy-global-perceptions-of-the-united-states/. Over time, withdrawal will lessen this perception and slow the creation of enemies.

U.S., allied, and civilian combat deaths in Afghanistan

Despite misconceptions to the contrary, the war in Afghanistan actually grew more deadly over time.

Withdrawal honored democratic and constitutional principles

War creates acute legal and ethical needs for public approval at home. Yet war in Afghanistan became less popular the longer it dragged on, which strained the legitimacy of plans to fight indefinitely. The further the mission drifted from what Congress initially intended, the thinner its legitimacy became, subverting the ideals America hoped to proliferate. Withdrawal honored these ideals and brought U.S. foreign policy closer in line with healthy legal limits.

The U.S. Constitution was designed on the intuitive principle that ordinary Americans deserve a say in where, why, and whether their government kills in their name. The president commands the armed forces, but only Congress—the people’s more direct representatives—can take the weightier step of declaring war. In such a system, leaders cannot strategize as if their constituents’ will to fight were inexhaustible. Resolve is a scarce resource, and one long since expended in Afghanistan.

Even 12 years before the withdrawal, President Obama’s surge was only politically feasible when paired with a withdrawal timeline. He explicitly rejected calls for “open-ended escalation” that “would commit us to a nation building project of up to a decade.”15Barack Obama, “Transcript of Obama Speech on Afghanistan,” December 2, 2009, https://www.cnn.com/2009/POLITICS/12/01/obama.afghanistan.speech.transcript/index.html. More than a decade later, Americans were even less enthused about fighting indefinitely. Over 70 percent supported withdrawal at the time of President Biden’s decision, and strong majorities continued to support it even during the unsightly evacuation.16Dina Smeltz and Emily Sullivan, “US Public Supports Withdrawal from Afghanistan,” Chicago Council on Global Affairs, August 9, 2021, https://www.thechicagocouncil.org/commentary-and-analysis/blogs/us-public-supports-withdrawal-afghanistan; Dan Balz, Scott Clement, and Emily Guskin, “Americans Support Afghanistan Pullout—but Not the Way It Was Done, a Post-ABC Poll Finds,” Washington Post, September 3, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/post-abc-poll-biden-afghanistan/2021/09/02/5520cd3e-0c16-11ec-9781-07796ffb56fe_story.html; Ted Van Green and Carroll Doherty, “Majority of U.S. Public Favors Afghanistan Troop Withdrawal; Biden Criticized For His Handling of Situation,” Pew Research Center, August 31, 2021, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/08/31/majority-of-u-s-public-favors-afghanistan-troop-withdrawal-biden-criticized-for-his-handling-of-situation/.

Critics argued these views were weakly held and unlikely to swing election outcomes. This may be true, but it does not matter.17Madiha Afzal and Israa Saber, “Americans Are Not Unanimously War-weary on Afghanistan,” Brookings Institute, March 19, 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2021/03/19/americans-are-not-unanimously-war-weary-on-afghanistan/; Paul Miller, “Afghanistan Didn’t Have to End This Way,” The Dispatch, August 13, 2021, https://thedispatch.com/p/afghanistan-didnt-have-to-end-this; Kevin Baron, “Petraeus Trashes Biden Decision to Quit Afghanistan,” Defense One, April 14, 2021, https://www.defenseone.com/threats/2021/04/petraeus-trashes-biden-decision-quit-afghanistan/173359/. Americans’ understandable fatigue at two decades of Afghanistan updates should not be used to marginalize their objections, nor normalize war waged quietly by technocrats hiding from public referendum. A wary and divided home front is ill-positioned to prevail in sustained conflicts abroad, as the Vietnam War illustrated. And warring by the passive indifference of the governed perversely inverts our constitutional default from peace until Congress clamors for war, to war until voters are impacted enough to care.18Daniel DePetris, “Checks and Balances on War Powers,” Defense Priorities, April 2, 2021, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/checks-and-balances-on-war-powers.

That the United States remained in Afghanistan as long as it did shows how warped its constitutional balance has become. The invasion was originally authorized to target those responsible for 9/11, just three days after the attacks. More than 20 years later, almost all responsible are long dead—yet the 2001 authorization continues to be abused for purposes far beyond the intent or imagination of its rattled and grieving authors. It has led to military operations in 85 nations, with combat troops in 15 and airstrikes in seven—very few of which could be named by your average American. It’s led to the Patriot Act, no-fly lists, NSA spying, and a secret drone program used to kill U.S. citizens without trial, each curtailing Americans’ freedom more sharply than terrorists ever could. Withdrawal was only a first step to curtailing these abuses—but it was a needed first step.19Stephanie Savell et al., “U.S. Counterterrorism Operations 2018–2020”, Brown University Costs of War Project, December 7, 2020, https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/files/cow/imce/papers/2021/US%20Counterterrorism%20Operations%202018-2020%2C%20Costs%20of%20War.pdf.

Withdrawal focused the West’s strategic attention

Before invading Afghanistan, the United States was a global hegemon enjoying unrivaled military, economic, and technological primacy. Military debacles in the greater Middle East are a significant reason why each of these advantages have significantly degraded 20 years later.

First, war in Afghanistan distracted American strategists from graver threats that grew quietly over time. While the United States was mired in asymmetric warfare, both Russia and China invested in conventional warfighting capabilities. Even as the United States gradually became attuned to the growing possibility of conflict in Taiwan or Ukraine, the need to protect U.S. servicemembers from actual and ongoing conflict in Afghanistan prompted overinvestment in counterinsurgency platforms. It also impeded a necessary shift away from land power into the naval and air power decisive in an Asian conflict.

Deployments to Afghanistan also overstretched military resources at the tactical and operational level. As any soldier will tell you, training requirements already far outpace the number of training hours available. Time spent preparing for one mission necessarily reduces readiness in another. Emphasizing COIN doctrine and nation-building to a generation of warfighters degraded readiness on the core competencies of near-peer conflict and prompted disproportionate investment in jobs better left to civilian agencies. This is the danger of a “Swiss Army knife” military. Withdrawing from Afghanistan let the U.S. military refocus on developing comparative advantages where they’re needed most.

Finally, war in Afghanistan diverted Europe’s attention from its own security at home. After 9/11, NATO invoked Article V for the first time in its history, eager to show that collective defense was not one-directional. Although NATO allies were certainly following the United States’ lead, their combined 7,000 troops in country actually exceeded America’s military footprint at the start of 2021.20Geir Moulson and Kathy Gannon, “Most European Troops Exit Afghanistan Quietly After 20 Years,” Associated Press, June 30, 2021, https://apnews.com/article/europe-afghanistan-health-coronavirus-pandemic-9c1c4f5732c032ba85865aab0338a7a3. Allied help was appreciated, but it would have been better cashed-in elsewhere. For example, several of these same NATO allies still lag the organization’s target of spending 2 percent of GDP on defense, enabling continued overreliance on the United States even as U.S. power and interests in Europe waned. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine illustrates this problem. The heavier NATO’s military burden, the less far “burden sharing” went towards actual defense against Russia. Withdrawal refocused the alliance on defending Europe: the original function for which it’s best suited.

In these ways, withdrawal critics undersold the costs of continued war in Afghanistan. War is more than just presence or support. It is more dangerous to civilians, to our soldiers, to our reputation, and to our strategic attention. It costs more money and has more stringent constitutional requirements. Naturally, it gets a shorter leash than mere deterrence, or a Marshall Plan, or anything we do in Japan. Peace can last for 70 years; war should not.

War was not protecting Americans from terrorism

The counterterrorism argument for remaining in Afghanistan failed on many levels. First, terrorists do not need a “safe haven” in order to plan and conduct attacks.21Michael Innes, “The Safe Haven Myth,” Foreign Policy, October 12, 2009, https://foreignpolicy.com/2009/10/12/the-safe-haven-myth/; Daniel L. Davis, “Debunking the Safe Haven Myth,” Defense Priorities, May 6, 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/debunking-the-safe-haven-myth. Even if they did, Afghanistan is unlikely to become a safe haven for terrorists, since the Taliban have strong incentive to dissuade the United States from returning. Even if those threatening the West did return to Afghanistan in force, the United States could combat them with advanced over-the-horizon capabilities. These capabilities are deemed sufficient in dozens of other poorly governed spaces from which terrorists currently operate, including some assessed to pose greater threats than Afghanistan. Besides, the litany of costs described above were vastly disproportionate to the scale of overall terror risk.

After 9/11, the United States adopted a series of internal reforms—like fortifying cockpit doors and sharing intelligence between foreign and domestic investigations—intended to better defend Americans from terrorist attacks. This “domestic hardening,” combined with more vigilant policing, has successfully thwarted subsequent attacks on U.S. soil. A Brown University report found that the “vast majority of these unsuccessful attacks had been prevented through the use of traditional law enforcement tools.”22Savell, “U.S. Counterterrorism Operations.”

By contrast, the extensive overseas war on terror has woefully failed to reduce the number or gravity of terrorist threats abroad.23Savell, “U.S. Counterterrorism Operations.” The U.S. invasion did weaken Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan, and it has not mounted a major attack since. But the war also dispersed Al-Qaeda affiliates to Pakistan and other places, then led to their replacement by ISIS-K. And overall, the State Department’s list of Foreign Terrorist Organizations has more than doubled since 2001, while total terrorist recruitment, attacks, and fatalities have also increased. “Our defenses are far stronger,” The Atlantic summarized, “but what we have to defend against has outpaced our progress.” 24Steven Brill, “Is America Any Safer?” Atlantic, September 2016, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/09/are-we-any-safer/492761/.To go backwards after so much cost in blood and treasure was a tragic error.

Despite this lack of progress, terrorism poses very little danger to Americans and is given vastly disproportionate attention by media and military alike.25Jeffrey Rogg and Andrew Stigler, “Full of Sound and Fury: Afghanistan’s Tragedy Becomes America’s Drama,” Just Security, November 17, 2021, https://www.justsecurity.org/79250/full-of-sound-and-fury-afghanistans-tragedy-becomes-americas-drama/. Including 9/11, Americans’ annual risk of dying in a terrorist attack from 1975 to 2017 was roughly 1 in 4.4 million—some eight times lower than one’s annual risk of being struck by lightning. Further reducing these tiny risks—even if it were effective—is not worth very much money. Offensive counterterror operations are only worthwhile if they’re virtually free, which the war in Afghanistan was not. A defensive, nonmilitary strategy would be perfectly sufficient moving forward, with over-the-horizon strikes available for emergencies.

War was not helping Afghanistan

Upheaval in Afghanistan has unwound economic and political progress, and the United States should immediately loosen or remove sanctions that cruelly exacerbate the crisis. But to cite these tragic circumstances as an argument against withdrawal assumes such tragedies were preventable, as opposed to merely postponable. Truly preventing them would have required either staying forever or staying for long enough to make progress “stick” without Americans holding it up. The first 20 years did not make progress much stickier; there is no reason to suspect 20 more years would have, either.

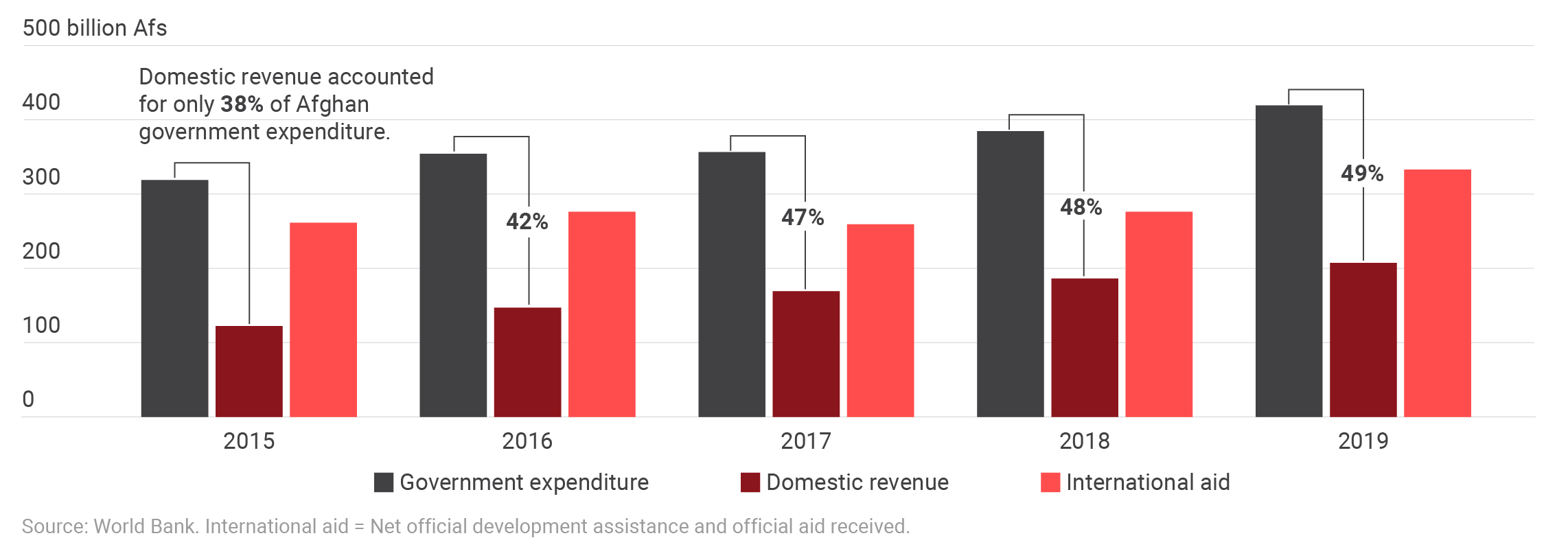

Military spending made Afghan democracy less responsive to its citizens than it was to foreign funders. A 2020 report from the Afghanistan Analysts Network detailed how the predictable incentives of a “rentier state”—a state with a budget and GDP dominated by outside income—conspired to stagnate progress in Afghanistan, entrenching inequality and corruption while weakening accountability.26Kate Clark, “The Cost of Support to Afghanistan: New Special Report Considers the Reasons for Inequality, Poverty and a Failing Democracy,” Afghanistan Analysts Network, May 29, 2020, https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/en/special-reports/the-cost-of-support-to-afghanistan-new-special-report-considers-the-reasons-for-inequality-poverty-and-a-failing-democracy/. As Farah Stockman described in The New York Times:

[War] became the Afghan economy…[dwarfing] every other economic activity, apart from the opium trade…Over two decades, the U.S. government spent $145 billion on reconstruction and aid and an additional $837 billion on war fighting, in a country where the G.D.P. hovered between $4 billion and $20 billion per year. Economic growth has risen and fallen with the number of foreign troops in the country.…

[Such] surreal amounts of cash poisoned the country…embittering those who didn’t have access to it and setting off rivalries among those who did… Why build a factory or plant crops when you can get fabulously wealthy selling whatever the Americans want to buy? Why fight the Taliban when you could just pay them not to attack?27Farah Stockman, “The War on Terror Was Corrupt From the Start,” New York Times, September 13, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/13/opinion/afghanistan-war-economy.html.

Afghanistan as a rentier state

International aid accounted for much of Afghanistan’s overall government expenditures, making it more responsive to outside funders than its own citizens.

Such rampant corruption made the Afghan Republic dysfunctional. Public services were provided inconsistently, if at all, and very often required bribes. Public officials were often ghosts, collecting salaries for positions that existed on paper only. Hundreds of schoolrooms were likewise imaginary, sitting empty and unused (if they were even built).28Sarah Chayes, “Afghanistan’s Corruption Was Made in America,” Foreign Affairs, September 3, 2021, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2021-09-03/afghanistans-corruption-was-made-in-america. Policemen extorted drivers at “informal” highway checkpoints. Provincial governors framed rival tribes as Taliban so U.S. forces would fight on their behalf. Courts collected lawyers’ fees, then failed to resolve disputes anyway. Some estimates put bribes at 13 percent of Afghanistan’s GDP. In the eyes of many Afghans, such outrages were worse than the Taliban, whose religious piety at least motivated integrity (corruption was rare under Taliban rule).29Chayes, “Afghanistan’s Corruption.”

Disillusionment with this corruption undercut the legitimacy of the Afghan Republic. In a country of 40 million people, only 1.8 million voted in the most recent presidential election in 2019. Of these, Ashraf Ghani was said to have won 50.64 percent—but few can know if that’s true, since allegations of ballot-stuffing were rampant. Both leading candidates declared victory and held separate inauguration ceremonies on the same day, casting the entire nation into a months-long political crisis. Negotiations subsequently produced a power-sharing deal—just as they had five years prior, when the same two candidates squared off in another election marked by fraud. Democracy is a strong word for such a system. It is not one the United States had a duty to defend.

U.S. presence also poisoned progress by framing it as foreign. The irony of external efforts to inspire national identity is that nothing so animates Afghan nationalism as deeply ingrained resistance to foreign domination. Lingering U.S. forces tarred democracy with the smudge of occupation, whereas fighting un-Islamic invaders and their perceived puppet state only legitimized the Taliban. Over time, the United States may have built a nation after all, of exactly the opposite sort it intended.

No wonder, then, that the war was going poorly long before the withdrawal. By 2019, the Taliban held more territory than at any point since 2001. A Brookings Institute report from this January concluded “the Taliban is ascendant in Afghanistan and…the United States does not have the capacity, at any reasonable cost, to reverse that trend, even with a sustained military presence.”30Vanda Felbab-Brown, “In Afghanistan, Different Priorities Means Vastly Different policies,” Brookings Institute, January 15, 2001, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2021/01/15/in-afghanistan-different-priorities-means-vastly-different-policies/. The speed of Afghanistan’s collapse last summer proved such warnings prescient. Many Afghans were willing to fight for a salary, but relatively few were willing to die for what they saw as a doomed a puppet government.

Finally, Afghanistan’s development was hampered by growing recognition that the order upheld by U.S. support was necessarily impermanent. U.S. leaders could not convince Afghans that American troops would remain for decades if they could not even say so to Americans without inciting public outcry. This not only undercut negotiating leverage, but inclined Afghans to short-term thinking, which was unhelpful to building enduring institutions. Far from laying conditions for peace, U.S. presence kept the country in limbo, obscuring pathways to organic growth that could only emerge in its absence.31Carter Malkasian, The American War in Afghanistan: A History (New York: Oxford Scholarship Online. 2021).

Nothing President Biden decided could change this reality. If he did not withdraw, the next president might. In fact, his likely 2024 opponent already tried to do so. Polls showed Americans in both parties wanted out, and the enemy knew this. Time was necessarily on their side.

Given these obstacles, U.S. presence could only plausibly be called “sustainable” (as it was time and again by withdrawal critics) in terms of what intervention cost—never in terms of what it bought. This weakened the case for buying Afghan rights one year at a time, even if the costs were as low as advertised.

U.S. credibility is enhanced by dissolving peripheral commitments

International commitments are bound by what is possible and cost-effective. Despite overblown but predictable hand-wringing that “abandoning” Afghans would make other allies doubt the reliability of U.S. commitments abroad, rational allies understand the United States cannot offer them a blank check. In fact, blank-check commitments are themselves uncredible, and abandoning them enhances credibility elsewhere.32Daryl Grayson Press, Calculating Credibility: How Leaders Assess Military Threats (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005), https://books.google.com/books?id=jecGSD9PSh0C&lpg=PP1&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false; Stephen M. Walt, “Afghanistan Hasn’t Damaged U.S. Credibility,” Foreign Policy, August 21, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/08/21/afghanistan-hasnt-damaged-u-s-credibility/.

The United States fought for the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan for 20 years, at a price exceeding $2 trillion. It continued to fight long after its core self-interest of decimating Al-Qaeda and punishing the Taliban were achieved and long after it became clear to most observers that the nation-building enterprise was doomed. If this sends our allies any message at all, it’s that the United States will stubbornly err on the side of overcommitment to them from jingoistic pride. If the withdrawal sends a message, it’s that the United States is increasingly able to distinguish core from peripheral interests and invest in them proportionally—which motivates allies to become more vital to, and less dependent on, the United States.

Hopefully, this will eventually enable the United States to rebalance its commitments in line with its actual interests. Until then, the resources freed up by withdrawal make the United States better able to honor other commitments. The beneficiaries of these commitments should feel reassured that their partner is no longer so overextended.

Withdrawing from Afghanistan was long overdue

By the time President Biden acknowledged these realities, withdrawal from Afghanistan was long overdue. The United States had little to gain from postponing it any further. Risk from terror attacks was small, manageable, and not meaningfully reduced by continued presence overseas. A self-sufficient Afghan Republic was not on the horizon. U.S. credibility was not on the line. To remain in Afghanistan was to prolong a conflict killing dozens of innocents per day, without serving any strategic or humanitarian purpose.

Withdrawal, by contrast, achieved significant moral, financial, and strategic gains. It relieved an overextended military; conveyed firm national priorities; saved tens of billions of dollars per year; and honored the obvious wishes of the American people. It freed up mental and material resources to focus on more important challenges. It gave much of the world one less reason to hate or attack the United States. And it ended a war once called endless, closing the book on a painful chapter in two countries’ histories. Restoring a proper balance to American foreign policy will require President Biden and his successors to make more brave choices moving forward, but he deserves real credit for getting started.

Portions of this explainer originally appeared in the Yale Journal of International Affairs.

Endnotes

- 1Rory Stewart, “America Was Finally Using Biden’s Afghanistan Strategy. Then He Pulled the Plug,” Washington Post, August 16, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2021/08/16/afghanistan-biden-withdrawal-military/.

- 2Rory Stewart, “Failure, and the Villains of the Western Campaign in Afghanistan,” August 19, 2021, in Western Way of War, produced by RUSI, podcast, 22:30, https://rusi.org/podcasts/western-way-of-war/episode-60-rory-stewart-failure-and-villains-western-campaign-afghanistan.

- 3Max Boot, “Twenty Years of Afghanistan Mistakes, but This Preventable Disaster Is on Biden,” Washington Post, August 15, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2021/08/15/twenty-years-afghanistan-mistakes-this-preventable-disaster-is-biden/.

- 4Neta C. Crawford, “Afghanistan’s Rising Civilian Death Toll Due to Airstrikes, 2017–2020,” Brown University Costs of War Project, December 7, 2020, https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/files/cow/imce/papers/2020/Rising%20Civilian%20Death%20Toll%20in%20Afghanistan_Costs%20of%20War_Dec%207%202020.pdf.

- 5Hyonhee Shin and Joyce Lee, “Factbox: U.S. and South Korea’s Security Arrangement, Cost of Troops,” Reuters, March 7, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-southkorea-usa-alliance/factbox-u-s-and-south-koreas-security-arrangement-cost-of-troops-idUSKBN2AZ0S0.

- 6Afghanistan Study Group, “Afghanistan Study Group Final Report,” U.S. Institute of Peace, February 3, 2021, https://www.usip.org/publications/2021/02/afghanistan-study-group-final-report-pathway-peace-afghanistan.

- 7“Afghan Civilians,” Brown University Costs of War Project, accessed October 8th, 2021, page updated as of April 2021, https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/costs/human/civilians/afghan.

- 8“The Week in Charts: Afghanistan, Haiti, the Coronavirus and More,” August 20, 2021, The Economist, https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2021/08/20/the-week-in-charts-afghanistan-haiti-the-coronavirus-and-more.

- 9Mark Hannah and Caroline Gray, “Democracy in Disarray: How the World Sees the U.S. and Its Example,” Eurasia Group Foundation, May 2021, https://egfound.org/2021/05/modeling-democracy-democracy-in-disarray/#full-report.

- 10Global Indicators Database, “Opinion of the U.S.,” Pew Research Center, updated March 2020, https://www.pewresearch.org/global/database/indicator/1/; Luke Baker, “Research Explores What 1.3 Billion Muslims Think,” Reuters, April 7, 2008, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-religion-islam-book/research-explores-what-1-3-billion-muslims-think-idUSL0768852020080407.

- 11Anand Gopal, “The Other Afghan Women,” New Yorker, September 6, 2021, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/09/13/the-other-afghan-women; International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clinic at Stanford Law School and Global Justice Clinic at NYU School of Law, “Living Under Drones: Death, Injury and Trauma to Civilians from US Drone Practices in Pakistan,” 2012, https://www-cdn.law.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Stanford-NYU-Living-Under-Drones.pdf; Christopher J. Coyne and Abigail R. Hall, “The Drone Paradox: Fighting Terrorism with Mechanized Terror,” The Independent Review 23, no. 1 (2018): 51–67. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26591799.

- 12Audrey Kurth Cronin, “Why Drones Fail,” Foreign Affairs, July/August 2013, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/somalia/2013-06-11/why-drones-fail.

- 13David Alexander, “Retired General Cautions Against Overuse of ‘Hated’ Drones,” Reuters, January 7, 2013, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-afghanistan-mcchrystal-idUSBRE90608O20130107.

- 14“Future Foreign Policy: Global perceptions of the U.S.,” Webinar from Atlantic Council with Caroline Gray, Washington, DC, June 16, 2021, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/event/future-foreign-policy-global-perceptions-of-the-united-states/.

- 15Barack Obama, “Transcript of Obama Speech on Afghanistan,” December 2, 2009, https://www.cnn.com/2009/POLITICS/12/01/obama.afghanistan.speech.transcript/index.html.

- 16Dina Smeltz and Emily Sullivan, “US Public Supports Withdrawal from Afghanistan,” Chicago Council on Global Affairs, August 9, 2021, https://www.thechicagocouncil.org/commentary-and-analysis/blogs/us-public-supports-withdrawal-afghanistan; Dan Balz, Scott Clement, and Emily Guskin, “Americans Support Afghanistan Pullout—but Not the Way It Was Done, a Post-ABC Poll Finds,” Washington Post, September 3, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/post-abc-poll-biden-afghanistan/2021/09/02/5520cd3e-0c16-11ec-9781-07796ffb56fe_story.html; Ted Van Green and Carroll Doherty, “Majority of U.S. Public Favors Afghanistan Troop Withdrawal; Biden Criticized For His Handling of Situation,” Pew Research Center, August 31, 2021, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/08/31/majority-of-u-s-public-favors-afghanistan-troop-withdrawal-biden-criticized-for-his-handling-of-situation/.

- 17Madiha Afzal and Israa Saber, “Americans Are Not Unanimously War-weary on Afghanistan,” Brookings Institute, March 19, 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2021/03/19/americans-are-not-unanimously-war-weary-on-afghanistan/; Paul Miller, “Afghanistan Didn’t Have to End This Way,” The Dispatch, August 13, 2021, https://thedispatch.com/p/afghanistan-didnt-have-to-end-this; Kevin Baron, “Petraeus Trashes Biden Decision to Quit Afghanistan,” Defense One, April 14, 2021, https://www.defenseone.com/threats/2021/04/petraeus-trashes-biden-decision-quit-afghanistan/173359/.

- 18Daniel DePetris, “Checks and Balances on War Powers,” Defense Priorities, April 2, 2021, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/checks-and-balances-on-war-powers.

- 19Stephanie Savell et al., “U.S. Counterterrorism Operations 2018–2020”, Brown University Costs of War Project, December 7, 2020, https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/files/cow/imce/papers/2021/US%20Counterterrorism%20Operations%202018-2020%2C%20Costs%20of%20War.pdf.

- 20Geir Moulson and Kathy Gannon, “Most European Troops Exit Afghanistan Quietly After 20 Years,” Associated Press, June 30, 2021, https://apnews.com/article/europe-afghanistan-health-coronavirus-pandemic-9c1c4f5732c032ba85865aab0338a7a3.

- 21Michael Innes, “The Safe Haven Myth,” Foreign Policy, October 12, 2009, https://foreignpolicy.com/2009/10/12/the-safe-haven-myth/; Daniel L. Davis, “Debunking the Safe Haven Myth,” Defense Priorities, May 6, 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/debunking-the-safe-haven-myth.

- 22Savell, “U.S. Counterterrorism Operations.”

- 23Savell, “U.S. Counterterrorism Operations.”

- 24Steven Brill, “Is America Any Safer?” Atlantic, September 2016, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/09/are-we-any-safer/492761/.

- 25Jeffrey Rogg and Andrew Stigler, “Full of Sound and Fury: Afghanistan’s Tragedy Becomes America’s Drama,” Just Security, November 17, 2021, https://www.justsecurity.org/79250/full-of-sound-and-fury-afghanistans-tragedy-becomes-americas-drama/.

- 26Kate Clark, “The Cost of Support to Afghanistan: New Special Report Considers the Reasons for Inequality, Poverty and a Failing Democracy,” Afghanistan Analysts Network, May 29, 2020, https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/en/special-reports/the-cost-of-support-to-afghanistan-new-special-report-considers-the-reasons-for-inequality-poverty-and-a-failing-democracy/.

- 27Farah Stockman, “The War on Terror Was Corrupt From the Start,” New York Times, September 13, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/13/opinion/afghanistan-war-economy.html.

- 28Sarah Chayes, “Afghanistan’s Corruption Was Made in America,” Foreign Affairs, September 3, 2021, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2021-09-03/afghanistans-corruption-was-made-in-america.

- 29Chayes, “Afghanistan’s Corruption.”

- 30Vanda Felbab-Brown, “In Afghanistan, Different Priorities Means Vastly Different policies,” Brookings Institute, January 15, 2001, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2021/01/15/in-afghanistan-different-priorities-means-vastly-different-policies/.

- 31Carter Malkasian, The American War in Afghanistan: A History (New York: Oxford Scholarship Online. 2021).

- 32Daryl Grayson Press, Calculating Credibility: How Leaders Assess Military Threats (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005), https://books.google.com/books?id=jecGSD9PSh0C&lpg=PP1&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false; Stephen M. Walt, “Afghanistan Hasn’t Damaged U.S. Credibility,” Foreign Policy, August 21, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/08/21/afghanistan-hasnt-damaged-u-s-credibility/.

More on Middle East

November 19, 2025

November 19, 2025

November 18, 2025