May 26, 2021

The inevitable rise of China: U.S. options with less Indo-Pacific influence

Key points

- China is destined to be the leading power in East Asia. Its economy will soon be at least one-and-a-half times that of the U.S. (measured by PPP), it is catching up to the U.S. in technological capabilities, and it has higher levels of human capital.

- Chinese advantages in East Asia are compounded by geographic proximity and hence deeper economic ties to the countries of the region compared to the U.S.

- The U.S. can still be more powerful if it acts in accordance with other countries, but most nations have shown a preference for accommodation over confrontation.

- Though the U.S. cannot prevent China from establishing itself as the dominant power in East Asia, it is not threatened by this and should focus on balancing in ways that bring it prosperity via trade and avoid catastrophic war.

Long-term implications of the rise of China

Shortly before his first address to Congress on April 28, President Biden told a group of reporters that “they’re going to write about this point in history … about whether or not democracy can function in the twenty-first century … can you get consensus in a timeframe that can compete with autocracy?”1Brian Stelter, (@brianstelter), Twitter, April 28, 2021, https://twitter.com/brianstelter/status/1387470612952752134. National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan informed CNN that the administration was “looking out at Xi Jinping’s China, Vladimir Putin’s Russia, and the pitch that they are making more overtly now than ever before … that the autocratic model, the non-democratic model is a better model for actually solving problems.” Sullivan then added, “Joe Biden in his bones believes they are wrong.”2Jeremy Diamond, “Joe Biden Can’t Stop Thinking About China and the Future of American Democracy,” CNN, April 29, 2021, https://www.cnn.com/2021/04/29/politics/president-joe-biden-china-democracy/index.html. Yet if the Biden administration wants to bet the future of democracy on the U.S. maintaining its edge over China, especially in its own backyard, democracy itself may be in trouble. It would be better to focus on strengthening American democracy while accepting the rise of China as a manageable concern for the United States, as long as Washington adopts a more restrained policy toward the Indo-Pacific.

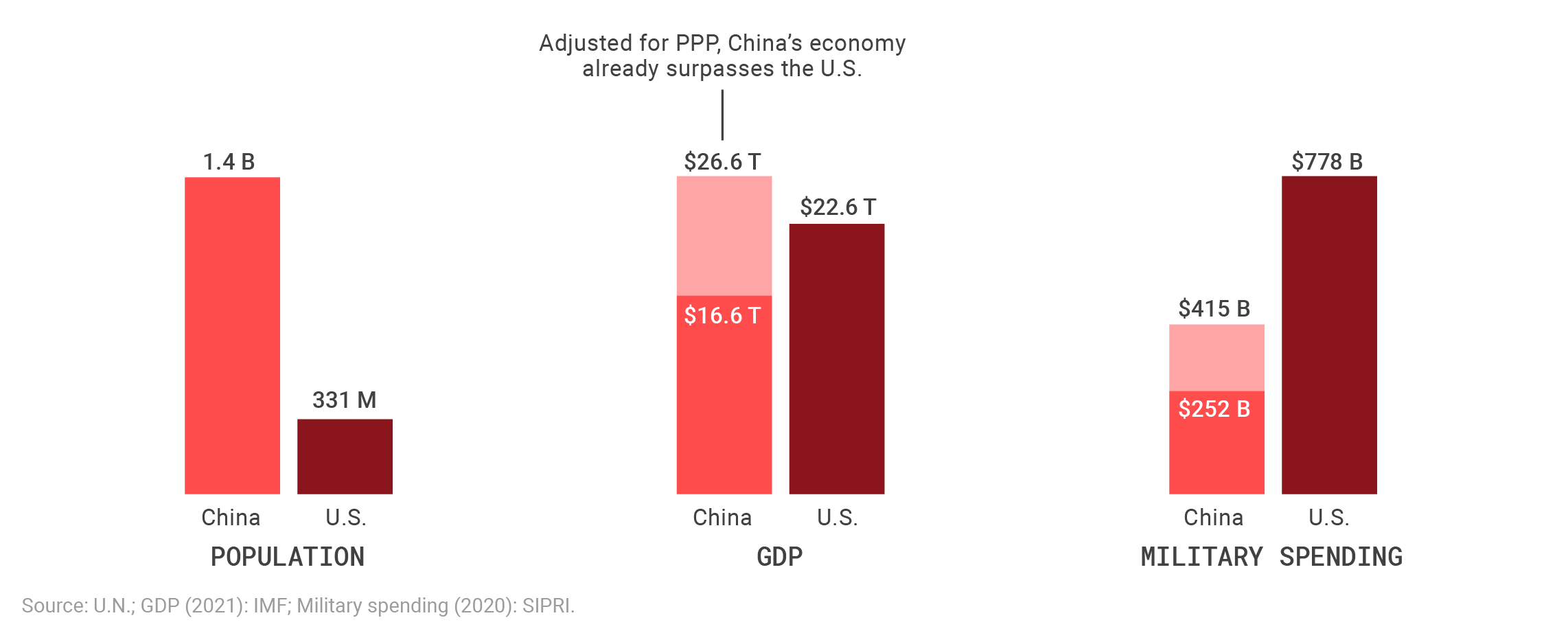

Population, GDP, and military spending of China and the U.S.

China’s population is about four times as large as the U.S.; its economy already surpasses the U.S. measured in PPP; and its military spending is concentrated regionally, whereas the U.S. has global commitments.

The U.S. and China are engaged in not only a rivalry, but a power transition. Only a generation ago, China was a poor nation of limited geopolitical significance after the collapse of the Soviet Union, and its relations with the U.S. were judged almost exclusively through an economic lens. Free-market reforms ushered in by Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s, and the integration of China into the world financial and economic system, resulted in a sustained period of economic growth that has few parallels. According to David Mann, the global chief economist at Standard Chartered, “From the end of the 1970s onwards we have seen what is easily the most impressive economic miracle of any economy in history.”3Virginia Harrison and Daniele Palumbo, “China Anniversary: How the Country Became the World’s ‘Economic Miracle,’” BBC, October 1, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/business-49806247. Despite predictions made by many analysts, China neither democratized nor collapsed.4Gordon G. Chang, The Coming Collapse of China (New York: Random House, 2001); Jack A. Goldstone, “The Coming Chinese Collapse,” Foreign Policy 99 (1995): 35–53. Instead, it rapidly grew, developing an urbanized middle class and a technologically sophisticated private sector while maintaining strict top-down political control, violating western ideals of democracy and infringing on the civil liberties of its citizens, a combination many American observers assumed was all but impossible. In fact, an argument was made that as China developed economically, the country would also liberalize politically, a prediction that could not have been more wrong.5“Full Text of Clinton’s Speech on China Trade Bill,” New York Times, March 9, 2000, https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/library/world/asia/030900clinton-china-text.html.

It is not simply that China is now a “peer competitor,” as many admit.6James Dobbins, Howard J. Shatz, and Ali Wyne, “Russia Is a Rogue, Not a Peer; China Is a Peer, Not a Rogue: Different Challenges, Different Responses,” RAND Corporation, 2019, https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PE310.html; John J. Tkacik Jr., “Hedging Against China.” Heritage Foundation, April 17, 2006, https://www.heritage.org/asia/report/hedging-against-china. In terms of absolute power as measured by purchasing power parity (PPP), China will be, even by conservative estimates, economically one-and-a-half times larger than the U.S. within the next few decades. Even using GDP as measured by market exchange rates (MER), which may exaggerate relative American wealth, China will pass the U.S. within the next decade and increase the gap between the two powers into the foreseeable future. It is approaching or has surpassed the U.S. in many important metrics for measuring human capital and scientific and technological innovation, though this has been aided and accompanied by massive amounts of IP theft and a surveillance state that represses individual rights and makes mass opposition to the government unlikely. While the U.S. and China are close to peer competitors now, the factors that have propelled the faster growth of the latter remain.

Middle-income countries grow faster than the wealthiest nations. Because Chinese per capita GDP is still low compared to the U.S., economic models predict it will continue to rise in terms of relative power. While it is true Chinese growth has slowed relative to what it was at its peak, this should not be taken to imply that the two powers are now growing at anywhere near the same rate. China is not in the process of simply catching the U.S., but rather surpassing it by a considerable measure, in a power shift that has been accelerated by how the two nations have responded to the coronavirus pandemic.7Jonathan Cheng, “China Is First Major Economy to Return to Growth Since Coronavirus Pandemic,” Wall Street Journal, July 15, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-is-first-major-economy-to-return-to-growth-since-coronavirus-pandemic-11594865317. The advantages that Beijing has in East Asia are compounded by geography and, relative to the U.S., its narrow international focus.

The challenge this power shift poses to the U.S. depends on what it wants in East Asia. If American leaders stick to realistic and achievable goals relevant to U.S. security and prosperity, they can be accomplished through a focus on domestic growth and relying on the countries of the region to potentially check any Chinese threat. If, in contrast, the U.S. seeks to assume the responsibility of defending virtually every country in the Indo-Pacific and maintain the same balance of power that existed three decades ago when China was a third-world country, it will fail and increase the possibility of a cataclysmic war.

This report investigates the long-term implications of Chinese regional hegemony. In a world in which the two powers are peer competitors, the future is uncertain, and leaders are free to make decisions across a wide range of possibilities likely to fundamentally change facts on the ground. When, in a certain region, one nation has an overwhelming preponderance of power, we can be more confident it will dominate that area as long as it desires to do so. While we cannot predict much about what China will use its power for, at the very least we should expect it to seek to gain more influence in its region at the expense of the U.S. and become more likely to succeed in disputes between the two nations in which each side seeks out the cooperation of others. China will be able to assert economic and diplomatic dominance over its own region even if the U.S. maintains or increases its military presence in nations like Japan and South Korea.

Checking the rise of China through alliances is unlikely, as the countries of East Asia generally do not see it as a threat to the same extent the U.S. does; nor do they share concerns about the internal human rights situation of that country or other issues, like autonomy for Hong Kong, that American policymakers have prioritized. Moreover, contemporary military alliances in East Asia actually give the U.S. little in terms of diplomatic advantage, as disputes over Huawei and other issues reveal. Even if other countries become more willing to let the U.S. defend them militarily, American influence can still decline. Given these facts, and the greater ability of China to bring about economic and diplomatic pressure on the region due to geography, East Asian countries are more likely to accommodate it than the U.S. while avoiding decisively aligning with either power.

While American leaders talk about ways to “confront China”—which usually involves some combination of stressing human rights, economic decoupling, and expanding military commitments in the Indo-Pacific—none of their suggestions will fundamentally alter the power shift currently underway. Given this reality, the U.S. should pursue two goals in the coming decades: (1) increase its prosperity through trade and (2) avoid crises and war. On this last point, that can be done by reducing its military footprint; limiting provocative actions, like unnecessary freedom of navigation operations in the South China Sea or declaring that U.S. forces will defend Taiwan; and halting even implicit calls for regime change. This would not only decrease tensions, but also potentially help the human rights situation in China by reducing perceptions of threat. Effectively pursuing long-term American interests in the region must begin with clarity about what the U.S. can realistically accomplish given its distance from East Asia and weakening position over time. Those hoping democracy will win out in the global marketplace of ideas should focus less of their energy on foreign confrontation and more on reforming domestic institutions.

The triumph of economic and geopolitical reality in the Indo-Pacific

International relations theorists often think of power in terms of actual or potential.8Jeffrey Hart, “Three Approaches to the Measurement of Power in International Relations,” International Organization (1976): 289–305. A country like Japan might have little actual military strength due to domestic political choices, but it may be called a powerful state because its status as a wealthy economy with advanced technology gives it the potential to assert itself more forcefully if it chooses. At the opposite end of the spectrum is a nation like North Korea, which is extremely poor but can menace its neighbors due to its heavy military investment.9Chung-in Moon and Sangkeun Lee, “Military Spending and the Arms Race on the Korean Peninsula,” Asian Perspective (2009): 69–99. Despite such real-world anomalies in which there is a wide gap between economic and military power, the two usually go together. In the words of Robert Gilpin, to many scholars “the pursuit of wealth and pursuit of power are indistinguishable.”10Robert Gilpin, War and Change in World Politics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1981): 68.

Regardless, a country like North Korea, because it is poor, has no economic leverage it can use against other states. For great powers like China and the U.S., whose military capabilities are supported by successful economies and large populations, rather than lopsided investment in that sector, economic and military power will tend to converge, especially when they are threatened.11William D. Baker and John R. Oneal, “Patriotism or Opinion Leadership? The Nature and Origins of the ‘Rally ‘round the Flag’ Effect,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 45, no. 5 (2001): 661–687; John R. Oneal and Anna Lillian Bryan, “The Rally ‘Round the Flag Effect in U.S. Foreign Policy Crises, 1950–1985,” Political Behavior 17, no. 4 (1995): 379–401. Through economic forecasting, we can understand how much pressure each state will be able to apply in the coming decades and, if necessary, which country will be better positioned to achieve victory in the event of armed conflict. Even if the U.S. is militarily stronger today, the extent to which China can hope to pose a challenge to U.S. hegemony depends on the future economic prosperity and scientific capabilities of China, both of which will be assessed below.12Mike Sweeney, “Assessing Chinese Maritime Power,” Defense Priorities, October 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/assessing-chinese-maritime-power; Stephen G. Brooks and William C. Wohlforth, “The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers in the Twenty-First Century: China’s Rise and the Fate of America’s Global Position,” International Security 40, no. 3 (2016): 7–53. Countries with more economic power can leverage that through carrots and sticks in their trade relationships and invest and develop capabilities in both soft power and various forms of data gathering, including espionage.

Analysts often call China a “peer competitor” or a “near-peer competitor” to the U.S.13Thomas J. Christensen, “Posing Problems Without Catching Up: China’s Rise and Challenges for U.S. Security Policy,” International Security 25, no. 4 (2001): 5–40. This phrase conjures up an image of two countries that are and will remain at a level of parity. Yet calling the U.S. and China peer competitors today is like saying the same about Germany and France in 1880. While this was technically true, the former was in the process of surpassing the latter and becoming much more economically and militarily formidable.14John F. V. Keiger, France and the World Since 1870 (London: Hodder Arnold Publications, 2001): 112–117. Such are the relative positions of the U.S. and China today; the countries are peer competitors now, but one is likely to gain a clear advantage over the other in the coming decades, at least in its own region.

How can we be confident that China will surpass the U.S. in terms of economic power? The neoclassical growth model is one of the most fundamental ideas in economics.15Robert M. Solow, “A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 70, no. 1 (February 1956): 65–94. Technological innovation combined with level of investment help determine the rate of growth in a particular country. Poorer countries will save more since they are technologically underdeveloped and can expect to see greater return to their investment. As countries get wealthier, however, they are on the technological frontier and the marginal return to capital is lower. Thus, rich countries consume more, save less, and ultimately experience lower rates of economic growth.

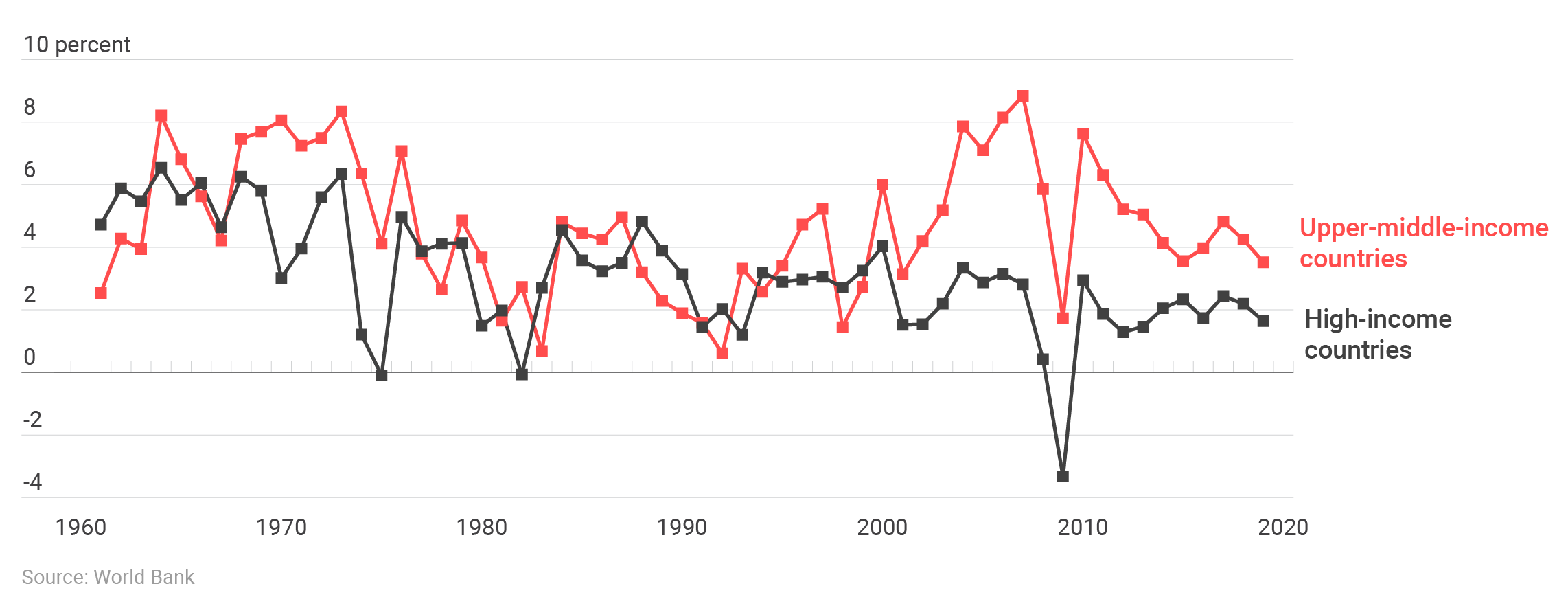

This model has received a high level of empirical support. The figures below show the average GDP growth for high-income and upper-middle-income countries for each year between 1961 and 2019, aggregated and relative to the U.S. dollar, and the growth rates for China and the U.S. between 1962 and 2020, based on the local currency of each nation.16Upper-middle-income countries are those for which the Gross National Income per capita in 2019 was between $4,046 and $12,535. See metadata at https://data.worldbank.org/income-level/upper-middle-income. High-income countries are any of those nations which had an average GNI of $12,536 or higher in 2019, https://data.worldbank.org/country/XD. The numbers for these categories must be used with some caution, as the World Bank does not consider the fact that nations move between income categories. Nonetheless, to move from one category to another is generally a very slow process, and the countries that were higher income in 2019 have in most cases been consistently wealthier than what the dataset calls upper-middle-income countries, thus making the chart useful, especially in later years.

From 1961 to 2019, in 49 out of 59 years, the upper-middle-income countries on average outgrew the high-income countries. The picture is more lopsided over the last 20 years, with the upper-middle-income countries outgrowing the high-income countries in every year since 2000. This is in part because central planning has fallen out of favor with elites in the developing world, removing the main obstacle to the growth of poor countries.17James Gwartney and Robert Lawson, “Economic Freedom of the World: 2008,” Fraser Institute, September 15, 2008, https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/economic-freedom-of-the-world-2008-annual-report.

Average GDP growth for high-income and upper-middle-income countries

The economies of upper-middle-income countries have historically grown at a higher rate than those of high-income countries.

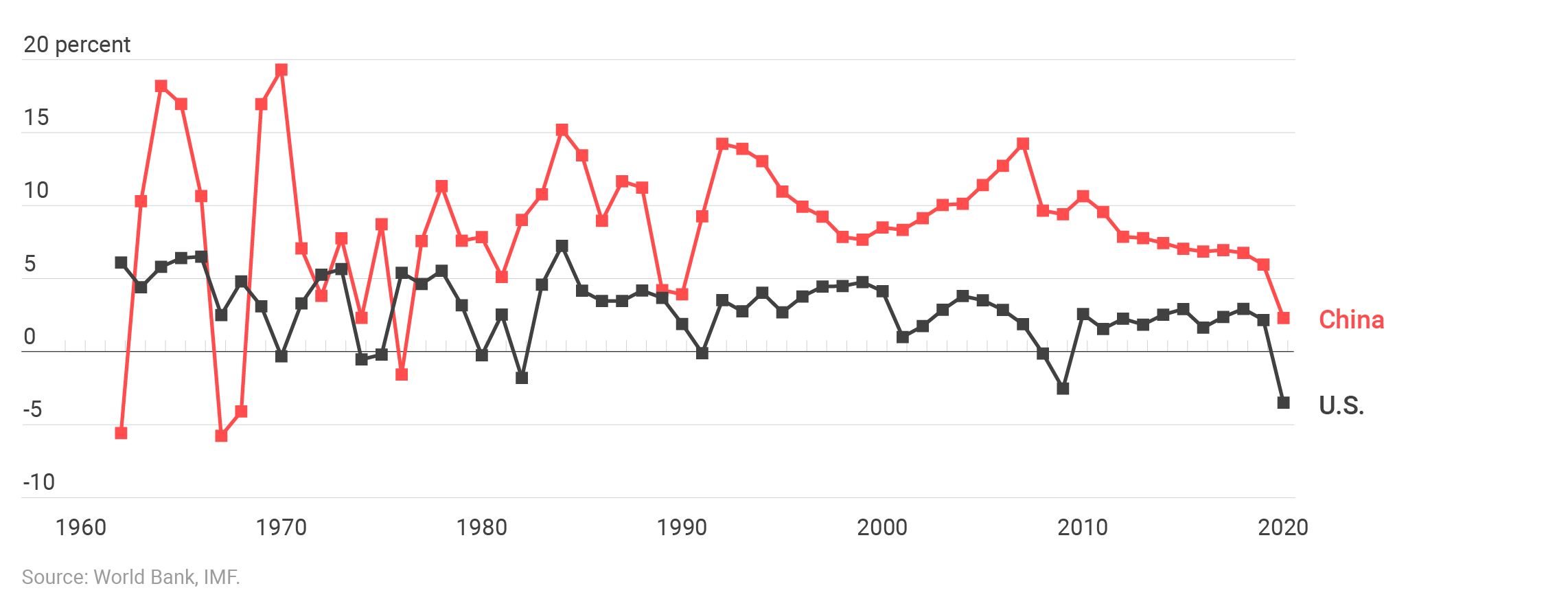

GDP growth rates for China and U.S.

China’s economy has grown at a higher rate than the U.S. economy for decades, especially after Beijing instituted economic reforms beginning in the 1980s.

The probability of China moving back toward a Soviet-style command economy is extremely low, despite the prominent role state-owned enterprises still play in its system today.18Max Büge, Matias Egeland, Przemyslaw Kowalski, and Monika Sztajerowska, “State-Owned Enterprises in the Global Economy,” VoxEU, May 2, 2013, https://voxeu.org/article/state-owned-enterprises-global-economy-reason-concern. And while the U.S. has in recent decades grown at about the same rate as other high-income countries, China has been growing much faster than even the middle-income average. This suggests China will become richer than the U.S. in the coming decades, as measured by GDP. While some American pundits have been predicting that the Chinese system would liberalize, see its growth rate crater, or even collapse, recent history indicates that authoritarian capitalism is stable, and today, such predictions are more fanciful than ever.19For prominent arguments about Chinese collapse, see Chang, The Coming Collapse of China; Goldstone, “The Coming Chinese Collapse.” For a list from 1998 to 2019 of extremely pessimistic accounts of the economic decline of China in the western press, with links, see Emil O. W. Kirkegaard, “China economy predictions: 1990–2020,” Clear Language, Clear Mind, November 24, 202, https://emilkirkegaard.dk/en/2020/11/china-economy-predictions-1990-2020/. For a recent more pessimistic take on the future of China that does not predict a collapse, see John Mueller, “China: Rise or Demise,” Cato Institute, May 18, 2021, https://www.cato.org/policy-analysis/china-rise-or-demise. Even if there were widespread opposition to the Chinese system of government, it is difficult to imagine how a powerful country with high levels of state capacity and control can be overthrown from below.20Edward Cunningham, Tony Saich, and Jesse Turiel, “Understanding CCP Resilience: Surveying Chinese Public Opinion Through Time,” Ash Center for Democratic Governance, July 2020, https://ash.harvard.edu/files/ash/files/final_policy_brief_7.6.2020.pdf. The only example of a great power collapsing over the last two centuries, outside of wartime, has been the Soviet Union, and even in this case it was not the result of protests from below or even mutinies within the security establishment, but decisions made by elites who believed the system needed to change.21Stephen Kotkin, Armageddon Averted: The Soviet Collapse, 1970–2000 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008). By all accounts, Chinese elites are growing more confident in their ability to rule as their nation rises.

In 2015, Jingyi Jiang and Kei-Mu Yi published a report for the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis calculating what Chinese GDP as measured by PPP will be relative to the U.S. in the coming decades.22Jingyi Jiang and Kei-Mu Yi, “How Rich Will China Become?” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, June 15, 2015, https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/2015/how-rich-will-china-become. Their estimate takes into account the fact that, as an upper-middle-income country, China should continue growing faster than the U.S., while also understanding that its growth will slow as time goes on. By 2036, they estimate Chinese per capita GDP will be 40 percent that of the U.S. Considering population projections, this means China would have an overall GDP that is 1.6 times larger than its main rival. By 2050, it could reach half the GDP per capita of the U.S., giving it 1.8 times the economy.23Population projections are taken from https://www.populationpyramid.net/. Using MER does not change the aggregate picture much, as China will pass the U.S. on this measure sometime in the next decade.24“The World in 2050: Will the Shift in Global Economic Power Continue?” PricewaterhouseCoopers, February 2015, https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/the-economy/assets/world-in-2050-february-2015.pdf. Such older estimates likely underestimate the extent and rapidity of the power shift, as 2020 saw China as the only major economy to report growth, meaning it made up more ground relative to the U.S. in GDP (MER) than in any other year on record, mainly due to differences in how the two countries responded to COIVD-19.25Jonathan Cheng, “China’s Economy Is Bouncing Back—And Gaining Ground on the U.S.,” Wall Street Journal, August 24, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/chinas-economy-is-bouncing-backand-gaining-ground-on-the-u-s-11598280917; Jonathan Cheng, “China Is the Only Major Economy to Report Economic Growth for 2020,” Wall Street Journal, January 18, 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-is-the-only-major-economy-to-report-economic-growth-for-2020-11610936187. While those who are more skeptical of the rise of China point to a population that will eventually decline and economic growth that is slower than what it was a decade ago, current projections take such factors into account, and China’s “slow” growth rate of the last few years before 2020 has still hovered around 6 percent, compared to around 2 percent for the U.S.26James T. Areddy and Chao Deng, “China’s Slowing Growth Underlines Stress Facing Its Economy in 2020,” Wall Street Journal, January 17, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/chinas-economic-growth-slows-to-6-1-as-trade-and-business-confidence-suffer-11579236022. While PPP is most useful for understanding military power, even looking at MER, China will be able to exercise more economic coercion than the U.S. within a decade, at least in theory, and also spend more on its military.27Whether to use PPP or MER as a measure of power depends on the purposes of the researcher. For measuring economic power as a proxy for realized or potential military power, PPP is superior. Less wealthy countries have lower labor costs, meaning China’s military spending can be more efficient per dollar spent. Also, MER is all but irrelevant for products built domestically, and China’s military expenditures rely on practically nothing that is imported from abroad. See Richard Connolly, “Russian Military Expenditure in Comparative Perspective: A Purchasing Power Parity Estimate,” CNA, October 2019, 20, https://www.cna.org/CNA_files/PDF/IOP-2019-U-021955-Final.pdf; Peter E. Robertson and Adrian Sin, “Measuring Hard Power: China’s Economic Growth and Military Capacity,” Defence and Peace Economics 28, no. 1 (2017): 91–111. Given that China’s military relies on domestic manpower and equipment built at home, PPP most accurately captures actual and potential Chinese military power. Using real GDP to compare military strength leads to absurd conclusions, like Russia being equal to the United Kingdom or France in military capabilities, despite the former being clearly superior in terms of manpower and access to advanced weapons systems. At the same time, MER is useful for understanding the potential for economic coercion abroad, as all international trade must go through international exchange markets. Countries through many parts of the world, but especially East Asia, will come to value economic ties with China more than those with the U.S. and therefore be more subject to leverage placed on them by the former.

While even a decade ago American analysts could claim China was, despite its economic accomplishments, well behind the U.S. in scientific development, the gaps they used to highlight have quickly closed.28Michael Beckley, “China’s Century? Why America’s Edge Will Endure,” International Security 36, no. 3 (2012): 41–78. For example, as of 2008, the U.S. registered 13,800 patents, compared to 828 for China. As of 2019, the Chinese number had risen to around 5,300, while the American number dropped below 13,000.29“Triadic Patent Families,” OECD, 2021, https://data.oecd.org/rd/triadic-patent-families.htm. In 2008, the U.S. had a level of R&D spending three times that of China, as computed by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). As of 2018, American total spending was only 20 percent higher. Between 2008 and 2018, American R&D spending increased by 21 percent compared to 217 percent for China.30“Gross Domestic Spending on R&D,” OECD, 2021, https://data.oecd.org/rd/gross-domestic-spending-on-r-d.htm. In 2020, China passed the U.S. in number of academic papers published in the natural sciences.31Noriaki Koshikawa, “China Passes U.S. as World’s Top Researcher, Showing Its R&D Might,” Nikkei Asia, August 8, 2020, https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Science/China-passes-US-as-world-s-top-researcher-showing-its-R-D-might. According to the National Science Foundation, since 2014, China has been spending more than the U.S. on experimental development, defined as work “directed toward producing new or improving existing products or processes.”32“The United States Invests More in Applied and Basic Research than Any Other Country but Invests Less in Experimental Development than China,” National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, December 2019, https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/2020/nsf20304/nsf20304.pdf.

Achievement scores for young people today are useful predictors of future scientific, economic, and technological accomplishment.33Eric A. Hanushek, “Economic Growth in Developing Countries: The Role of Human Capital,” Economics of Education Review 37 (2013): 204—212; Garett Jones, Hive Mind: How Your Nation’s IQ Matters so Much More than Your Own (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2015). Luckily, the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) gives similar standardized tests to 15-year-olds in countries across the world and allows for “apples-to-apples” comparisons. As of 2018, China had the highest reading, math, and science scores in the world, while the U.S. was in 13th place.34“PISA 2018 Results,” OECD, accessed May 5, 2021, https://www.oecd.org/pisa/publications/pisa-2018-results.htm. Chinese scores only came from the four major cities of Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang, so they are not representative of the country. Nonetheless, in 2015, the Chinese score in mathematics was higher than that of Massachusetts, which has been shown by domestic assessments to be the top performing American state, while science scores were about equal.35“State Results: Massachusetts Science Scores,” NCES, accessed May 5, 2021, https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/pisa/pisa2015/pisa2015highlights_7.asp; Hayley Glatter, “Massachusetts Test Scores Top Nation’s School Districts Again,” Boston Magazine, https://www.bostonmagazine.com/education/2018/04/10/massachusetts-best-schools-naep. The four Chinese cities represented in PISA have a total population of 180 million, compared to fewer than 7 million for Massachusetts, implying that the numbers from that state may represent more of an elite fraction of the national population than the Chinese sample. As one analyst put it, the math difference between Shanghai and Massachusetts in 2012 was similar to that between Massachusetts and Mexico.36Marc Tucker, “Are China’s PISA Scores Believable? A Different View,” NCEE, January 30, 2020, https://ncee.org/2020/01/are-chinas-pisa-scores-believable-a-different-view.

So, while 10 years ago, those who thought American hegemony would last indefinitely into the future could rest easy by ignoring GDP trends and looking at scientific innovation or human capital, these same metrics look different today. Of course, nothing is set in stone. The analysis above describes the most likely scenario: China will continue to grow like a middle-income country and the U.S. will continue to grow like a high-income country. This does not rule out the possibility of discontinuities or one or more “Black Swan” events.37Nassim Nicholas Taleb, The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. (New York: Random House, 2007). Analysts who predict the collapse of the current system or massive unrest within China in effect stake their analysis on the claim that the future will not closely resemble the past.

The problem with this view is those predicting a hard economic fall, or even collapse of China, have been consistently wrong for 30 years, as have even the more sober pessimists.38See endnote 4 and endnote 19. Moreover, analysts err in assuming that the only possible Black Swans are those that benefit the U.S. One can easily imagine scenarios in which the U.S. suffers a cataclysmic event that decreases its power, such as a move away from the dollar as the reserve currency of the world—a possibility that would have dire economic consequences in the U.S.39Enea Gjoza, “Counting the Cost of Financial Warfare,” Defense Priorities, November 2019, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/counting-the-cost-of-financial-warfare. The privilege the dollar enjoys means the U.S. could have more to lose from unforeseen events.

Differences in how the U.S. and China have handled the COVID-19 pandemic, which has already helped close the GDP gap, indicate the latter may have more state capacity to address novel challenges that arise in the future. As of May 2021, China had reported fewer than 5,000 deaths from the disease, with a flat curve, compared to at least 580,000 in the U.S., although new cases are now plummeting thanks to a successful vaccination effort.40The total American excess death toll in 2020 was around 522,000, though we cannot know for certain how many of those are due directly to the virus and how many are due to its indirect effects or other factors. See Steven H. Woolf, et al. “Excess Deaths from COVID-19 and Other Causes in the U.S., March 1, 2020, to January 2, 2021.” JAMA 2021, 325 (17): 1786–1789. While one may cast doubt on Chinese numbers, Western journalists visiting the country have long reported on life being largely back to normal, with Western businesses telling the same story, and nations having lifted travel restrictions on those coming from China, indicating that the statistics showing that Beijing got the virus under control early reflect reality.41“Council Agrees to Start Lifting Travel Restrictions for Residents of Some Third Countries,” European Council, June 30, 2020, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2020/06/30/council-agrees-to-start-lifting-travel-restrictions-for-residents-of-some-third-countries. In 2020, the Chinese economy grew 2.3 percent despite the pandemic, while the U.S. economy shrunk by 3.5 percent.42“World Economic Outlook: Managing Divergent Recoveries,” International Monetary Fund, April 2021, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2021/03/23/world-economic-outlook-april-2021. Recent history indicates that, if we take into account the possibility of Black Swans, we have reason to believe the analysis above underestimates the likelihood of China coming to economically dominate East Asia.

Other sources of Chinese power: proximity and priorities

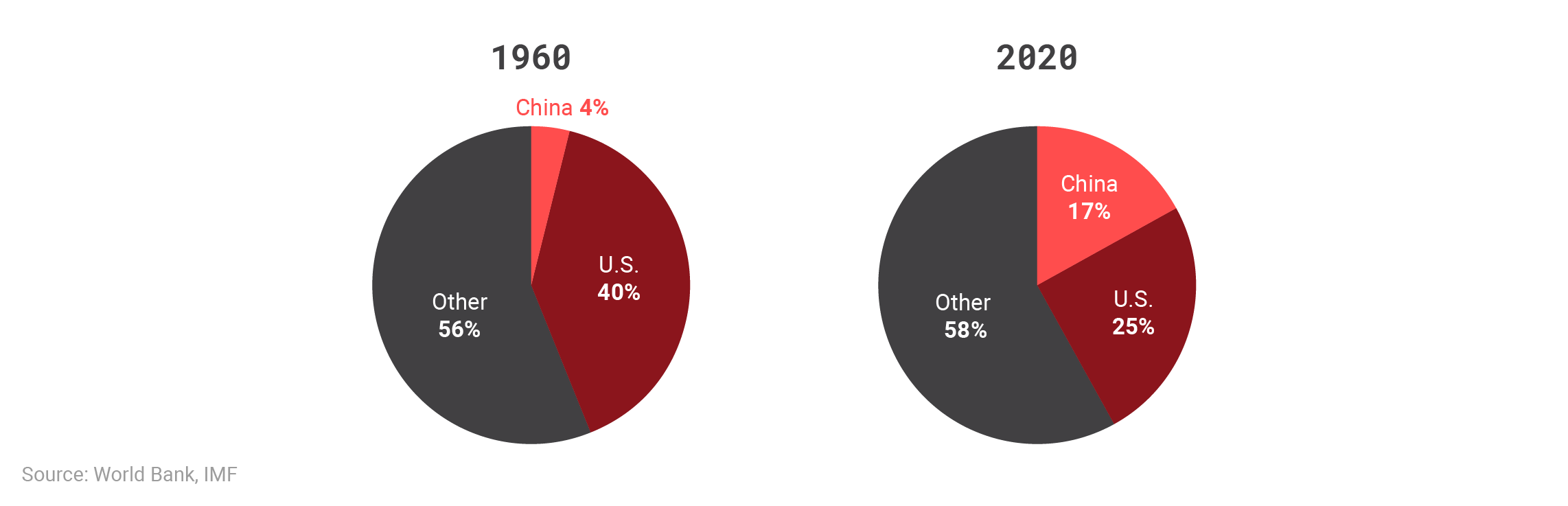

The figure below shows the percentage of global GDP represented by the U.S. and China in 1960 compared to 2020. In 1960, the U.S. contribution to global GDP was 40 percent and the Chinese equivalent 4 percent. Since then, the U.S. share has shrunk to 25 percent, and China’s has grown to 17 percent.

Share of global GDP (MER)

The U.S. commanded an outsized share of the global economy after World War II, but in recent years, China’s rise has moved its economy closer to parity.

China is in the process of economically surpassing the U.S. by all measures. To have as much say in East Asian affairs in the coming decades, the U.S. would have to care more about the region than China does. This is completely unrealistic and unwise, and contrary to the logic of post-World War II American hegemony, which relies on overwhelming American economic and military power to be a major player throughout the world. If Beijing decides to mount a challenge in the South China Sea or over Taiwan, it will do so knowing that it is in its own backyard and can bring more resources to bear in the case of conflict.

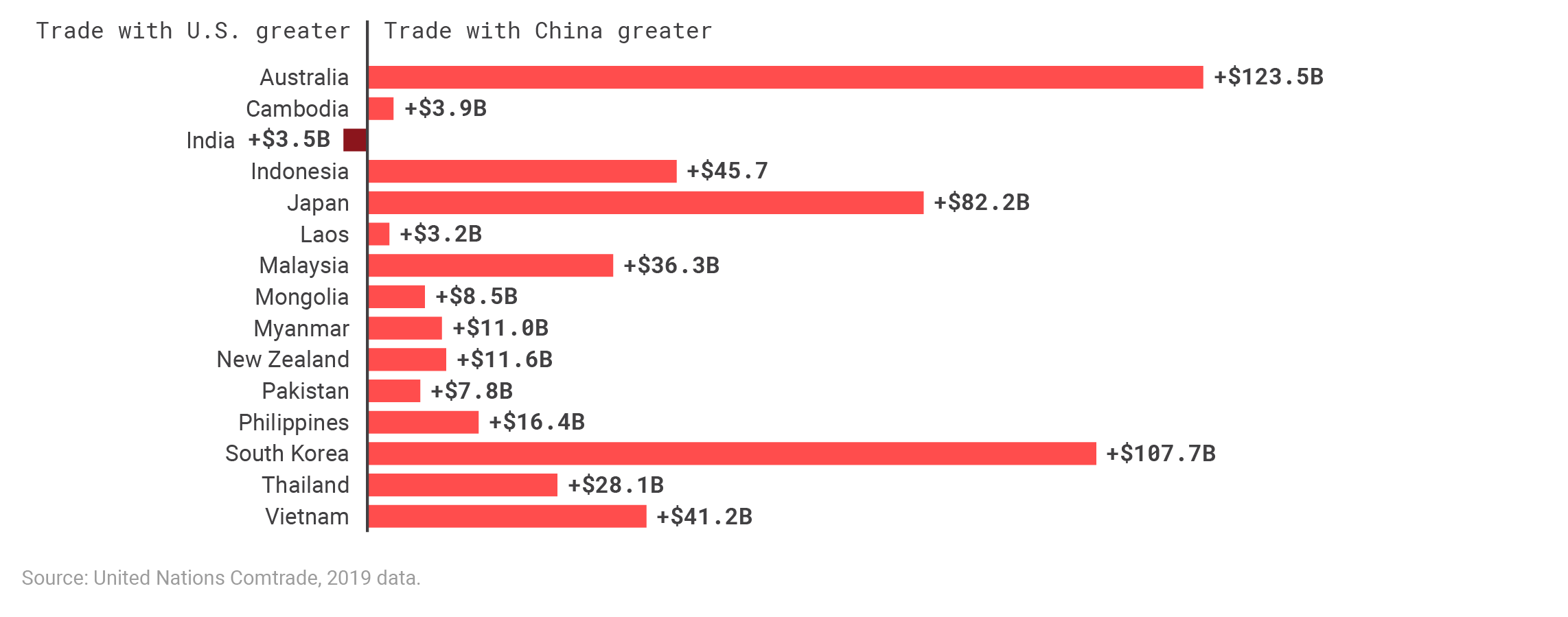

Of course, wars and power projection are not simply about absolute capabilities. They are also about geography and other commitments a state may have.43Mike Sweeney, “Assessing Chinese Maritime Power.” Both of these considerations further indicate that China will be the dominant power in East Asia, even if the U.S. continues to be stronger militarily over the decades.44Brooks and Wohlforth, “The Rise and Fall.” Geographic proximity is an advantage militarily because, in any potential conflict, a state has to worry less about the costs and risks of equipping and supplying personnel and weaponry far from home.45Colin Elman, “Extending Offensive Realism: The Louisiana Purchase and America’s Rise to Regional Hegemony,” American Political Science Review 98, no. 4 (2004): 563–576. Countries have greater economic ties with their neighbors than distant countries for similar reasons.46Henri L. F. De Groot, et al., “The Institutional Determinants of Bilateral Trade Patterns,” Kyklos 57, no. 1 (2004): 103–123. China has deeper trade relations than the U.S. with nearly every country in the Indo-Pacific.

These findings are independent of the strength of bilateral ties or cultural similarity between the U.S. and each individual nation. Even for New Zealand and Australia, bilateral trade with China is greater than with the U.S. The same is true for other U.S. allies that host large numbers of American personnel, like Japan and South Korea. GDP comparisons alone thus underestimate the advantage that China has over the U.S. in exerting economic pressure in East Asia.

Net difference in total trade in goods with U.S. vs. China in the Indo-Pacific (2019)

In 2019, India was the only country listed above to trade more in goods with the U.S. than with China.

The other advantage China has over the U.S. is its narrow focus on its own backyard. American commitments are global, while those of China are regional, an advantage it will lose only if it follows the U.S. model and overextends itself. The U.S. overseas footprint includes hundreds of foreign bases in dozens of countries, and it is obliged to defend countries that collectively represent around 25 percent of humanity and 75 percent of global GDP.47Michael Beckley, “The Myth of Entangling Alliances: Reassessing the Security Risks of U.S. Defense Pacts,” International Security 39, no. 4 (2015): 7–48. The U.S. is committed to not only balancing against China in East Asia, but also deterring Russia in Eastern Europe and defending its unofficial allies in the Middle East. These commitments have in recent years led to bloody, multi-decade wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, in addition to more limited interventions in countries such as Libya, Syria, Somalia, and Yemen, which have weakened the U.S.

China, in contrast, has shown no interest in establishing a substantial military presence far from its borders. It has small bases in Djibouti, Myanmar, and Tajikistan, but none of them include the capacity for a substantial permanent troop presence, and each is connected to a narrow mission.48Gerry Shih, “In Central Asia’s Forbidding Highlands, a Quiet Newcomer: Chinese Troops,” Washington Post, February 28, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/in-central-asias-forbidding-highlands-a-quiet-newcomer-chinese-troops/2019/02/18/78d4a8d0-1e62-11e9-a759-2b8541bbbe20_story.html. Over the next several decades, absent a shift toward a more restrained posture, the U.S. will be expected to spend diplomatic and political capital, and perhaps commit troops, to deal with major conflicts that might emerge throughout Latin America, Europe, the Middle East, and Africa. China will not and thus be able to narrowly focus on its regional goals.

The likely future

Given that, for the foreseeable future, China will be the most powerful country in the Indo-Pacific and have closer economic ties to its neighbors than the U.S., what can we forecast about the future of the region? The most obvious point of disagreement between the two nations is the status of Taiwan. The U.S. may continue to support Taipei while raising the costs of China starting a war. Yet even without an invasion, China will be able to bring economic pressure on other nations to take its side in disputes over the status of the island. Combined with economic pressure it can exert on Taiwan itself, one can imagine a scenario in which the island nation experiences “Finlandization.” Such a state of affairs can coexist with the U.S. continuing to provide military aid to that country.

While no one can predict what disputes the U.S. and China will have in the future on issues other than Taiwan, we can be relatively certain Beijing will become more likely to get its way as time goes on due to its greater ability to exercise economic and, in extreme cases, military coercion. Dartmouth College professors Stephen Brooks and William Wohlforth argue that countries cannot easily translate higher GDP into equivalently high levels of military capabilities, and the U.S. has the advantage of decades of investment in its defense sector.49Brooks and Wohlforth, “The Rise and Fall.” Even if true, such disadvantages may be overcome with time by a country that is wealthy and technologically advanced. Regardless, American deterrence capabilities may simply work to raise the costs of Chinese territorial aggression, while otherwise doing little to maintain American influence in the region. Recent decades have shown that there are limits on the ability of the U.S. to achieve foreign policy goals when they conflict with Chinese interests. Consider the dispute over the telecom giant Huawei and whether it should have a role to play in building the 5G infrastructures of various nations. Perhaps in response to a strong American pressure campaign, Australia, Japan, and Taiwan have enacted Huawei 5G bans. At the same time, countries like South Korea, Cambodia, and the Philippines make use of the technology.50Shaun Turton, “Cambodia 5G Set to Leapfrog ASEAN Rivals with Huawei and ZTE,” Nikkei Asia, September 5, 2019, https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/5G-networks/Cambodia-5G-set-to-leapfrog-ASEAN-rivals-with-Huawei-and-ZTE; “Huawei: Which Countries Are Blocking Its 5G Technology?” BBC, May 18, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-48309132. Note that the American troop presence in East Asia has not been decisive in how nations have thought about whether to welcome Huawei. Japan and South Korea, the two countries of the region that host the largest number of American troops, came down on opposite sides of the issue.

Also consider the situation in Hong Kong. In response to protests, China introduced a new National Security Law in the summer of 2020, clamping down on pro-democracy activism and other forms of dissent.51Laignee Barron, “‘It’s So Much Worse Than Anyone Expected.’ Why Hong Kong’s National Security Law Is Having Such a Chilling Effect,” Time, July 23, 2020, https://time.com/5867000/hong-kong-china-national-security-law-effect. The U.S. has been unable to form a united front against China, even rhetorically. Japan, which is more hawkish toward Beijing, would not join an American statement condemning the new law, although it did later join a G7 statement.52“Japan Declines to Join U.S., Others in Condemning China for Hong Kong Law: Kyodo,” Reuters, June 7, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-hongkong-protests-japan/japan-declines-to-join-us-others-in-condemning-china-for-hong-kong-law-kyodo-idUSKBN23E0DE; “G7 Statement on Hong Kong Electoral Changes,” U.S. Department of State, March 12, 2021, https://www.state.gov/g7-statement-on-hong-kong-electoral-changes/. India only condemned Chinese actions after a border clash that left dozens dead, indicating little actual interest in the underlying issue.53Sachin Parashar, “India Uses Hong Kong to Land Diplomatic Punch on China,” Times of India, July 2, 2020, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/in-a-first-india-speaks-up-on-hong-kong/articleshow/76737816.cms; Paul D. Shinkman, “India, China Face Off in First Deadly Clash in Decades,” U.S. News, June 16, 2020, https://www.usnews.com/news/world-report/articles/2020-06-16/dozens-killed-as-india-china-face-off-in-first-deadly-clash-in-decades. South Korea and the nations of Southeast Asia have not taken a strong position on Hong Kong.54Truston Yu, “Why is Southeast Asia Silent on Hong Kong?” Jakarta Post, June 9, 2020, https://www.thejakartapost.com/academia/2020/06/09/why-is-southeast-asia-silent-on-hong-kong.html. Only Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and most European countries have joined the U.S. in consistently condemning Beijing.55Adam Forrest, “European Leaders Condemn China’s ‘Deplorable’ New Hong Kong Security Law,” Independent, July 1, 2020, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/hong-kong-security-law-china-eu-ursula-von-der-leyen-a9595731.html. Whatever differences they have with China, there is clearly no appetite for most of the nations of the Indo-Pacific to challenge it over democracy or human rights issues. As American influence in East Asia recedes, we will see even fewer efforts from countries in the region toward confronting China over issues peripheral to their core interests.

Countries not only do not view China as a major threat in the way that the U.S. does, but they also continue to pursue economic integration. In the future, it is possible the continued rise of China will result in it becoming more of a potential threat. In response, its neighbors may take a different perspective. Yet while an even stronger China is more threatening, it is also a more powerful nation and one that will have more leverage over other states. Thus, although the pressures to balance against China may grow for security reasons, so can the pressures for accommodation for economic reasons. The rise of China has been foreseeable for at least two decades now and over the whole course of its growth, we have seen more accommodation than confrontation. It is difficult to see what threshold China would have to cross for this trend to be reversed, short of territorial aggression that it shows little sign of undertaking (excluding perhaps the notable exception of Taiwan). Countries of the region have either not seen China as a threat, or, if they do, the threat has been insufficient to compel them to sacrifice economic growth or other political objectives to do much about it.

In the future, new points of disagreement between the U.S. and China will emerge. Some of them will resemble the Huawei issue and relate to technologies that potentially have national security significance. Others will involve human rights, like the situations in Xinjiang and Hong Kong, or will be new issues. What is clear, however, is that the American ability to use its diplomatic and military power to get its way is limited and diminishing. While today, when the U.S. makes convincing other countries to ban Huawei a priority, it is met with mixed results, a similar situation in 20 years may see nearly all countries of the region take the side of Beijing if the U.S. even tries such a diplomatic initiative in the first place.

The current situation in the South China Sea shows how the future course of events may unfold. The U.S. rejects expansive Chinese claims in the region and occasionally sends ships through the area in freedom of navigation operations (FONOPs) to demonstrate that it considers it part of international waters.56Kyle Mizokami, “U.S. Sends Major Military Muscle to the South China Sea,” Popular Mechanics, July 6, 2020, https://www.popularmechanics.com/military/navy-ships/a33218348/us-military-south-china-sea. Yet occasional shows of force do not change the facts on the ground. China continues to build up its military capabilities in the area, including seven artificial islands that serve as bases.57Ankit Panda, “Are China’s South China Sea Artificial Islands Militarily Significant and Useful?” Diplomat, January 15, 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2020/01/are-chinas-south-china-sea-artificial-islands-militarily-significant-and-useful. In the coming decades, the U.S. will have to escalate its dispute with China to have any hope of reversing its control over the disputed waters by finding a way to hinder or roll back infrastructure gains. Simply sending naval ships through the area will not prevent Beijing from building up its military capabilities or exploiting contested resources. Just as American troops in South Korea did not prevent that nation from welcoming Huawei and accepting economic integration with China, U.S. willingness to commit military resources far from home may come to matter less and less for its ability to exercise power in the Far East.

Acknowledging the inevitable and avoiding catastrophe

The U.S. will not be able to contain China on its own. The only possible way to balance China is by working with allies. If the U.S. combined its power with that of countries like India and Japan, in addition to other states in the region, it may be able to surpass China in both military and economic resources. Since these other countries have more to fear from China than the U.S.—given the greater proximity and, potentially, wealth of the former—an argument can be made they may come together with the U.S. to form a balancing coalition against the potential regional hegemon.58Stephen M. Walt, The Hell of Good Intentions: America’s Foreign Policy Elite and the Decline of U.S. Primacy (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2018), 269. In recent years, American leaders have therefore called for an “alliance of democracies” to counter the rise of China.59David Brunnstrom and Daphne Psaledakis, “Pompeo Urges More Assertive Approach to ‘Frankenstein’ China,” Reuters, July 23, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-china-pompeo-idCAKCN24O310.

What would such an alliance look like? It would at the very least call for countries in the region to take a more assertive security posture. This would likely include more military investments and deepening security ties with the U.S. It would also require an economic component, with the countries of the region becoming less integrated with and economically dependent on China, thereby checking its rise and decreasing the potential for Beijing to exert diplomatic and financial pressure. This was the justification used to argue for the Trans-Pacific Partnership put forth during the Obama administration.60Kevin Granville, “The Trans-Pacific Partnership Trade Deal Explained,” New York Times, May 11, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/12/business/unpacking-the-trans-pacific-partnership-trade-deal.html.

The type of balancing coalition desired by many in Washington requires other countries to perceive Beijing in the same way that America does, as an aggressive power whose rise is itself a major problem worth sacrificing trade relationships and risking war to confront.61On the accommodationist stance most East Asian countries have taken towards Beijing, see David Chan-oong Kang, China Rising: Peace, Power, and Order in East Asia (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007). Yet there is little evidence that this is the case. To understand how we know this, it is important to distinguish between stated preferences, what people say they want, and revealed preferences, what they actually do.62Kenneth Train and Wesley W. Wilson, “Estimation on Stated-Preference Experiments Constructed from Revealed-Preference Choices,” Transportation Research Part B: Methodological 42, no. 3 (2008): 191–203. In this case in particular, stated preferences are particularly unreliable since countries have an incentive to free-ride off of American defense commitments. Even if countries feel no threat at all from China, an American troop presence can be a boon for the economy of the host nation, or for at least some narrow constituency.63Uk Heo and Min Ye, “U.S. Military Deployment and Host-Nation Economic Growth,” Armed Forces & Society 45, no. 2 (2019): 234–267. Moreover, it is possible some leaders speak out strongly against China for reasons of domestic politics, while taking no hostile action toward it, or actually seeking further integration.

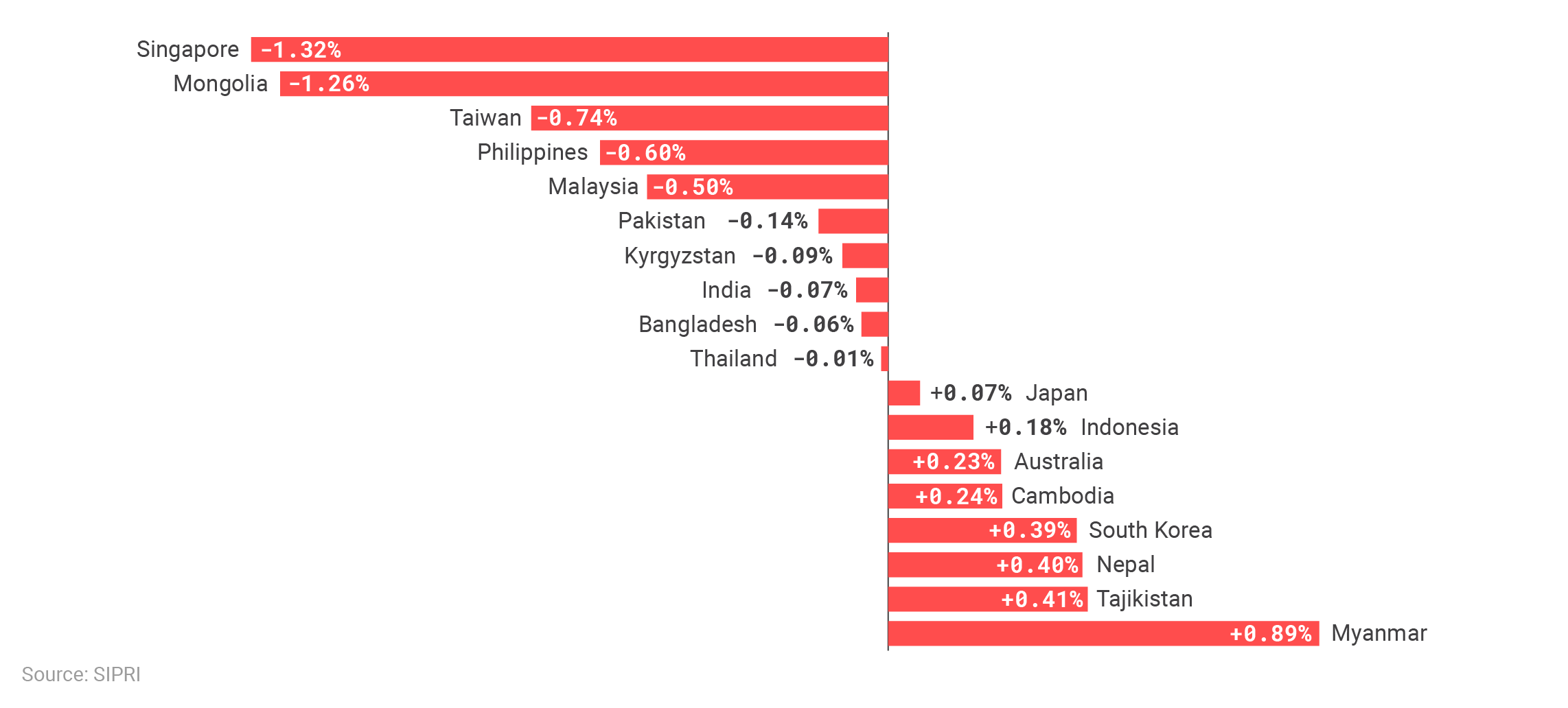

Revealed preferences indicate most of the countries of East Asia are not inclined to join the U.S. in a balancing coalition that involves either decoupling or large military investments. Examining trends in military spending and international trade demonstrates this fact. On the first of these, most countries in the region are not significantly increasing their military budgets as a percentage of GDP. Some have declined.

Change in military spending as a percentage of GDP (2000–2020)

As a share of each country’s GDP, annual defense spending has decreased for several Asian countries in the last two decades, including Taiwan and India.

One may object that countries like Japan and South Korea are happy to free-ride off of American defense commitments, so have no incentive to spend their own money. Yet there is little indication most countries that do not have defense treaties with the U.S. or host American personnel are taking the “threat” from China any more seriously than those that do. India, for example, has seen a decrease in its military spending as a percentage of GDP over the last two decades.

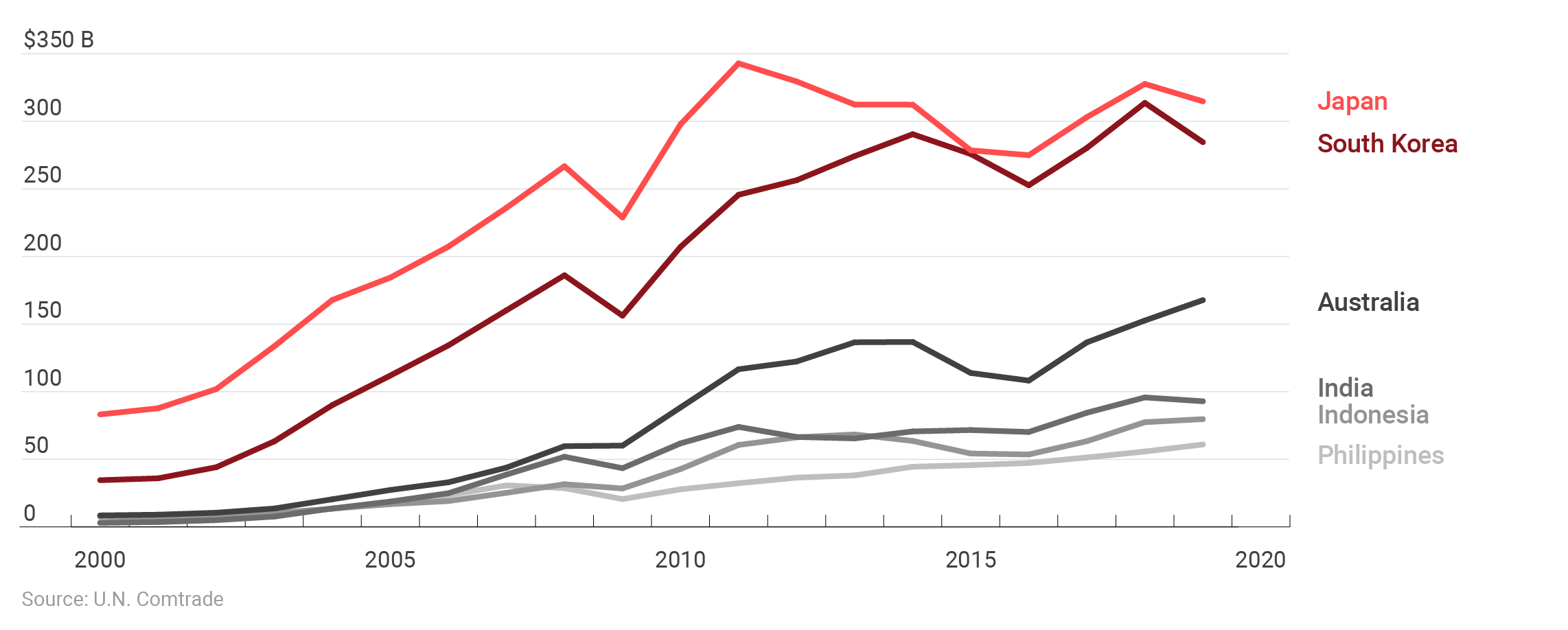

The second set of revealed preferences we can examine is trade relations with China. For a country that truly fears the rise of China, there are two disadvantages to increasing trade relations. First, it makes China wealthier, and thus potentially more powerful. Second, and more importantly, it gives China more leverage over the country with which it trades. Despite these facts, all countries in the region have seen their total trade with China increase significantly over the past two decades.

Total annual trade in goods with China

Each major economy in the Indo-Pacific region has seen its trade with China increase substantially.

If Indo-Pacific countries saw China as a threat, they would be calling for more of an American defense commitment. In 2019, reporting on Secretary of Defense Mark Esper’s trip to East Asia, The Wall Street Journal published the headline “The U.S.’s Quest for Military Unity on China Comes Up Short in Asia”64Nancy A. Youssef and Andrew Jeong, “The U.S.’s Quest for Military Unity on China Comes Up Short in Asia,” Wall Street Journal, November 21, 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-u-s-s-quest-for-military-unity-on-china-comes-up-short-in-asia-11574327273. with a story about how the countries of the region were uninterested in joining Washington in staking out a confrontational approach. The rise of China is foreseeable, and if countries are not willing to confront Beijing today, there is reason to doubt they will begin to do so once they are more economically integrated with an even more powerful neighbor.65Of course, one may object to the framing of this discussion as an issue of stated versus revealed preferences. One possibility is that leaders actually do fear China, but either have a high time preference, or care about their own personal interests more than those of their countries. The benefits of trade and lower military spending are achieved today, while the costs of making China more powerful and giving it leverage over one’s nation are likely to be felt many years down the line, when a different leader might be in charge. Shortsighted leaders, caring more about their political fortunes than the ultimate destiny of their nations, may be saying nothing at all about their forecasts regarding the future course of events when they allow trade with China to grow and military spending to stagnate. Whether we see the issue through the lens of national preferences or the self-interest of politicians, the implications are the same. Either countries in the Indo-Pacific do not fear China, or they have leaders who act in their short-term individual interests only and are unlikely to act strategically, and will be easily influenced by Beijing, along with domestic business interests and consumers that profit from trade.

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a global infrastructure investment strategy announced by the Chinese government in 2013, can be seen from this perspective. In 2015, the Chinese Development Bank announced it had built a database of $800 billion worth of projects in 64 countries related to the BRI, with $168 billion in infrastructure projects already in planning or under construction.66Ming Wan, The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank: The Construction of Power and the Struggle for the East Asian International Order (New York: Springer, 2016): 52. Morgan Stanley in 2018 forecasted that total Chinese spending on its BRI would reach as much as $1.3 trillion by 2027.67“Inside China’s Plan to Create a Modern Silk Road,” Morgan Stanley, March 14, 2018, https://www.morganstanley.com/ideas/china-belt-and-road. This may have been an overestimate, as spending has declined precipitously over the last few years.68James Kynge and Jonathan Wheatley, “China Pulls Back from the World: Rethinking Xi’s ‘Project of The Century,’” Financial Times, December 11, 2020, https://www.ft.com/content/d9bd8059-d05c-4e6f-968b-1672241ec1f6. Nonetheless, some Americans claim that accepting aid and loans from China can lead to it exerting undue influence on its partners, even trapping them in “debt slavery.”69H. R. McMaster, “How China Sees the World,” Atlantic, May 2020, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/05/mcmaster-china-strategy/609088/; Hal Brands, “What Does China Really Want? To Dominate the World,” Japan Times, May 22, 2020, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2020/05/22/commentary/world-commentary/china-really-want-dominate-world. Yet many of the countries involved do not see it this way, accepting BRI investments as in their interest.70Lee Jones, “China’s Belt and Road Initiative Is a Mess, Not a Master Plan,” Foreign Policy, October 9, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/10/09/china-belt-and-road-initiative-mess-not-master-plan. They may be mistaken, and American critics warning about the long-term impact of the BRI may be correct, but the countries accepting BRI funding disagree. History provides many examples of states “under balancing” in the face of a rising threat due to domestic political reasons; that may be happening here.71Randall L. Schweller, Unanswered Threats: Political Constraints on the Balance of Power (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006). It is easier to believe, however, that the U.S. does not better understand what is in the long-term interest of these countries than they themselves do, and that Washington is therefore engaging in threat inflation. Regardless, we should not expect nations to adopt a different perspective once they are more economically linked with a China that has only grown in stature.

Of course, all this can change if China becomes aggressive and shows an inclination to conquer other nations or threaten their sovereignty. Balancing coalitions are common in international politics, but they require perceptions of aggressive intent; as the modern Indo-Pacific shows, a potential threat is not enough.72For the alternative view, at least regarding great powers, see John J. Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (New York: Norton, 2001): 29–43. China is bordered by four nuclear powers—India, Pakistan, Russia, and North Korea—and next to Japan, a country with the third largest economy in the world and the potential to go nuclear on short notice. It is wrong to make policy based on the belief that a U.S. role is indispensable for there to be a check on potential Chinese aggression.

No one can be sure of Chinese intentions decades from now. Thus, even if there may be little evidence of aggressive plans being made today, there is no guarantee the government will not eventually seek to economically dominate or even conquer its neighbors.73Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics: 29–54. Nonetheless, nuclear weapons will remain a dominant factor in international politics, and China’s neighbors have the wealth to deter and defend themselves from potential aggression.

Economic coercion in the region by China is more likely, but given its rise, there is little the U.S. would be able to do to stop it. There is nothing the U.S.—from across the ocean—can offer the countries of the Indo-Pacific to stop them from trading with a country of 1.4 billion people and the largest economy in the world, located in their backyard. Any form of economic decoupling for these states would be extremely painful and therefore require a compelling reason.

The main point is that geopolitical and economic realities, not American grand strategy, will determine the future of East Asia. It is the height of hubris for Washington to believe it has more at stake or is better equipped than the countries of the region to deal with any challenges resulting from the rise of China. Thus far, accommodation has been the preferred response to new realities. If, at some indefinite point in the future, that changes, it will not be because Washington “showed leadership” or rallied the nations of the region, but because of Chinese behavior.

A better way forward

Today—after its “century of humiliation” (1839–1949) and the disaster of Maoism—China is emerging to reclaim its historical role as the dominant power in East Asia. While complaints are made about how the U.S. abetted this rise through welcoming it into the WTO, this likely only accelerated the process. The most important factor in the rise of China has been the move away from economic central planning in a politically stable environment. Given its effective governance, high human capital, and large population, once Beijing decided to liberalize its economy, the rise of China was all but inevitable.74On the deep roots of Chinese success, in terms of human capital and state capacity, see Diego Comin, William Easterly, and Erick Gong, “Was the Wealth of Nations Determined in 1000 BC?” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 2, no. 3 (2010): 65–97; Noel D. Johnson and Mark Koyama, “States and Economic Growth: Capacity and Constraints,” Explorations in Economic History 64 (2017): 1–20. Luckily, the nuclear status of its neighbors, and the potential to go nuclear in the case of Japan, make it unlikely Chinese growth will lead to war in East Asia, much less Beijing conquering its neighbors.

There is little the U.S. can do to stop the rise of China, and more ambitious balancing coalitions will emerge only in response to aggressive acts. Washington cannot keep China poor, nor force states in the region to form a balancing coalition they would otherwise avoid. What it can do, unfortunately, is make major mistakes in the hopes of thwarting the inevitable or going beyond what American security interests require in ways that lead to strained relations or even war. Understanding this leads to the following three policy suggestions.

1. Avoid war, which could go nuclear

The balance of power in East Asia is ultimately mostly not under the control of the U.S., so what can and should American leaders do about the coming state of affairs? First, the U.S. should forego provocative policies or military actions that may make war more likely for no discernable gain. As mentioned above, sending ships through the South China Sea will not do anything to prevent Beijing from dominating the region militarily or exploiting its resources. American FONOPs have not prevented China from building artificial islands in the South China Sea, and its military continues to work on building the infrastructure necessary to militarily dominate the area. If the U.S. deemed it vital to conquer Cuba, there would be nothing a superpower on the other side of the world could do to stop it short of going to war. This should be our understanding with regard to China and Taiwan.

By militarily investing in the Indo-Pacific region and taking provocative actions, like sending ships through the Taiwan Strait, the U.S. increases the probability of a great power war at great cost and for little benefit. The worst-case scenario in the case of America pulling back from the region in the short term would be a takeover of Taiwan. Yet even if China does take that step, this would likely not be seen as evidence of future aggressive intentions by the countries of the region, as they do not even recognize the independent status of the island. If China goes beyond Taiwan and seeks territory elsewhere, it risks provoking the balancing coalition among its neighbors that the U.S. has thus far been unable to build. Given the accommodationist strategy most Asian nations have adopted, it would not be in the interest of Beijing to make new claims on its neighbors beyond what it seeks to control in the South China Sea. Encouraging American allies to build up their own defensive capabilities can increase the costs of Chinese aggression in the region and effectively deter potential territorial threats.75Eugene Gholz, Benjamin H. Friedman, and Enea Gjoza, “Defensive Defense: A Better Way to Protect U.S. Allies in Asia,” Washington Quarterly 42, no. 4 (2019): 171–189.

American policy has been moving in the opposite direction. After much lobbying by the Department of Defense, its next budget is poised to increase funding for the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command.76Robbie Gramer and Jack Detsch, “The Pentagon’s Budget Wish List,” Foreign Policy, May 13, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/05/13/biden-security-pentagon-defense-budget-plans/. The U.S. conducted more FONOPs in the South China Sea in 2019 than in any other year.77David B. Larter, “In Challenging China’s Claims in the South China Sea, the U.S. Navy Is Getting More Assertive,” Defense News, February 5, 2020, https://www.defensenews.com/naval/2020/02/05/in-challenging-chinas-claims-in-the-south-china-sea-the-us-navy-is-getting-more-assertive/. The total number was nine, which risks escalation but does nothing to change the balance of power in the region. Should war actually break out between China and the Philippines, for example, the closest land-based U.S. forces are 1,000 miles away.78Zack Cooper and Gregory Poling, “America’s Freedom of Navigation Operations Are Lost at Sea,” Foreign Policy, January 8, 2019, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/01/08/americas-freedom-of-navigation-operations-are-lost-at-sea/. This fact is understood by everyone in the region, and American attempts to assert credibility by sailing through contested waters do not change the facts on the ground.

2. More forward-looking balancing

Collectively, the countries of the Indo-Pacific have enough resources and power to defend against China. Rather than expecting the U.S. to use its military as the primary force defending East Asia, American leaders should pull back and thus encourage states in the region to protect their own territory. This would involve encouraging them to invest in A2/AD technology and training, which seeks to prevent a foreign country from being able to conquer and occupy territory rather than pursuing a more offensive strategy. Unfortunately, American policy in East Asia has often taken a different approach, adopting an “offensive defense” strategy that seeks complete military supremacy over China and hold its entire territory at risk.79Gholz, Friedman, and Gjoza. “Defensive Defense.” As argued above, this is unsustainable under the likely GDP trajectories. Defense is cheaper and less risky than offense, even without thousands of miles of ocean between nations. American leaders should accept there will be less balancing against China if it is not seen as aggressive by its neighbors. The fact that the U.S. provides defense in the region encourages other countries to underinvest in their own militaries or, it may be more accurate to say, they would not invest more than they do already even if the U.S. left because the military threat is not what Washington perceives.

Regardless of which is true, balancing must be based on realistic assessments of the power of China, the ability of the U.S. to operate thousands of miles away from home, and the perceptions and interests of other nations in the Indo-Pacific. The perspectives of these nations—shaped by Chinese behavior, not the prerogatives of Washington—will largely dictate the extent to which any balancing coalition forms. A blue water navy, not committed to defending any particular nation but sufficient to defend the global commons, is enough to guarantee American safety and prosperity in the case of Chinese aggression.

3. Focus on U.S. prosperity, not Chinese internal politics

The final thing the U.S. should do is stop signaling its hopes of fundamentally changing who holds power in Beijing and instead focus on its own affairs. In July 2020, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo gave a speech on China that some hawks interpreted as calling for a policy of regime change.80Gordon G. Chang, “Mike Pompeo Just Declared America’s New China Policy: Regime Change,” National Interest, July 25, 2020, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/mike-pompeo-just-declared-america%E2%80%99s-new-china-policy-regime-change-165639. Critics of Beijing regularly argue that the Chinese take too dogmatic an approach to issues of national sovereignty, all but admitting that mutual hostility between the powers is rooted in the desire of many in the U.S. to overthrow the government of Xi Jinping and end CCP rule, if not militarily than by encouraging internal discord.81Hal Brands, “Democracy vs. Authoritarianism: How Ideology Shapes Great Power Conflict,” Survival 60, no. 5 (2018): 61–114; Daniel Tobin, “How Xi Jinping’s ‘New Era’ Should Have Ended U.S. Debate on Beijing’s Ambitions,” Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, March 13, 2020, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/testimonies/SFR%20for%20USCC%20TobinD%2020200313.pdf. Of course, the U.S. has no ability to overthrow, at acceptable cost, the Chinese government or fundamentally change its political culture. Setting such goals makes cooperation in areas like disease prevention and climate change more difficult.

Throughout history, countries have exercised power abroad due to economic success, the factor on which great power influence rests. For the U.S. to compete with China, it should invest internally: infrastructure improvements, GDP growth, improved educational outcomes, and other measures to increase innovation and wealth creation. While such goals are difficult to achieve, it is easy to see that increasing spending on a military competition with China in its own backyard is not helpful.

U.S. influence in East Asia is destined to diminish, but that does not make America less safe. Those most fearful of China who call for more military spending, overextension, and a commitment to marshalling allies do not present any policy ideas that can reverse underlying trends, even if adopted. Throughout the Indo-Pacific, China has the advantages of geography and a relatively passive attitude toward the affairs of the rest of the world. While those advantages will continue, it is in the process of approaching and surpassing the U.S. in all measures of economic power, and to a great extent in technological and scientific achievement, all of which can be converted into superior military strength if there is a will to do so. That reality is an argument to strengthen the U.S. internally to prepare for long-term competition, if necessary. Old habits of thinking, overly optimistic analyses assuming Chinese decline or collapse, and ignoring the basic principle of compound growth have prevented the U.S. from grappling with the speed and magnitude of the shifting balance of power we are experiencing. Washington is left with the choice of either adjusting to the new reality or risking catastrophe to try and stop what is inevitable.

President Biden’s vision of competition with China requires the U.S. to look inward. As he correctly recognizes, a country that cannot solve problems at home will be in no position to preserve its influence abroad. However, if the U.S. is to ensure democracy wins the war of ideas, the world’s most important democracy cannot set standards that are impossible to meet. Making America a model for the rest of the world is achievable, while maintaining itself as the dominant power in East Asia in the face of a rising China is not. All policies related to great power competition should proceed with that understanding in mind.

Endnotes

- 1Brian Stelter, (@brianstelter), Twitter, April 28, 2021, https://twitter.com/brianstelter/status/1387470612952752134.

- 2Jeremy Diamond, “Joe Biden Can’t Stop Thinking About China and the Future of American Democracy,” CNN, April 29, 2021, https://www.cnn.com/2021/04/29/politics/president-joe-biden-china-democracy/index.html.

- 3Virginia Harrison and Daniele Palumbo, “China Anniversary: How the Country Became the World’s ‘Economic Miracle,’” BBC, October 1, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/business-49806247.

- 4Gordon G. Chang, The Coming Collapse of China (New York: Random House, 2001); Jack A. Goldstone, “The Coming Chinese Collapse,” Foreign Policy 99 (1995): 35–53.

- 5“Full Text of Clinton’s Speech on China Trade Bill,” New York Times, March 9, 2000, https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/library/world/asia/030900clinton-china-text.html.

- 6James Dobbins, Howard J. Shatz, and Ali Wyne, “Russia Is a Rogue, Not a Peer; China Is a Peer, Not a Rogue: Different Challenges, Different Responses,” RAND Corporation, 2019, https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PE310.html; John J. Tkacik Jr., “Hedging Against China.” Heritage Foundation, April 17, 2006, https://www.heritage.org/asia/report/hedging-against-china.

- 7Jonathan Cheng, “China Is First Major Economy to Return to Growth Since Coronavirus Pandemic,” Wall Street Journal, July 15, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-is-first-major-economy-to-return-to-growth-since-coronavirus-pandemic-11594865317.

- 8Jeffrey Hart, “Three Approaches to the Measurement of Power in International Relations,” International Organization (1976): 289–305.

- 9Chung-in Moon and Sangkeun Lee, “Military Spending and the Arms Race on the Korean Peninsula,” Asian Perspective (2009): 69–99.

- 10Robert Gilpin, War and Change in World Politics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1981): 68.

- 11William D. Baker and John R. Oneal, “Patriotism or Opinion Leadership? The Nature and Origins of the ‘Rally ‘round the Flag’ Effect,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 45, no. 5 (2001): 661–687; John R. Oneal and Anna Lillian Bryan, “The Rally ‘Round the Flag Effect in U.S. Foreign Policy Crises, 1950–1985,” Political Behavior 17, no. 4 (1995): 379–401.

- 12Mike Sweeney, “Assessing Chinese Maritime Power,” Defense Priorities, October 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/assessing-chinese-maritime-power; Stephen G. Brooks and William C. Wohlforth, “The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers in the Twenty-First Century: China’s Rise and the Fate of America’s Global Position,” International Security 40, no. 3 (2016): 7–53.

- 13Thomas J. Christensen, “Posing Problems Without Catching Up: China’s Rise and Challenges for U.S. Security Policy,” International Security 25, no. 4 (2001): 5–40.

- 14John F. V. Keiger, France and the World Since 1870 (London: Hodder Arnold Publications, 2001): 112–117.

- 15Robert M. Solow, “A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 70, no. 1 (February 1956): 65–94.

- 16Upper-middle-income countries are those for which the Gross National Income per capita in 2019 was between $4,046 and $12,535. See metadata at https://data.worldbank.org/income-level/upper-middle-income. High-income countries are any of those nations which had an average GNI of $12,536 or higher in 2019, https://data.worldbank.org/country/XD. The numbers for these categories must be used with some caution, as the World Bank does not consider the fact that nations move between income categories. Nonetheless, to move from one category to another is generally a very slow process, and the countries that were higher income in 2019 have in most cases been consistently wealthier than what the dataset calls upper-middle-income countries, thus making the chart useful, especially in later years.

- 17James Gwartney and Robert Lawson, “Economic Freedom of the World: 2008,” Fraser Institute, September 15, 2008, https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/economic-freedom-of-the-world-2008-annual-report.

- 18Max Büge, Matias Egeland, Przemyslaw Kowalski, and Monika Sztajerowska, “State-Owned Enterprises in the Global Economy,” VoxEU, May 2, 2013, https://voxeu.org/article/state-owned-enterprises-global-economy-reason-concern.

- 19For prominent arguments about Chinese collapse, see Chang, The Coming Collapse of China; Goldstone, “The Coming Chinese Collapse.” For a list from 1998 to 2019 of extremely pessimistic accounts of the economic decline of China in the western press, with links, see Emil O. W. Kirkegaard, “China economy predictions: 1990–2020,” Clear Language, Clear Mind, November 24, 202, https://emilkirkegaard.dk/en/2020/11/china-economy-predictions-1990-2020/. For a recent more pessimistic take on the future of China that does not predict a collapse, see John Mueller, “China: Rise or Demise,” Cato Institute, May 18, 2021, https://www.cato.org/policy-analysis/china-rise-or-demise.

- 20Edward Cunningham, Tony Saich, and Jesse Turiel, “Understanding CCP Resilience: Surveying Chinese Public Opinion Through Time,” Ash Center for Democratic Governance, July 2020, https://ash.harvard.edu/files/ash/files/final_policy_brief_7.6.2020.pdf.

- 21Stephen Kotkin, Armageddon Averted: The Soviet Collapse, 1970–2000 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).

- 22Jingyi Jiang and Kei-Mu Yi, “How Rich Will China Become?” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, June 15, 2015, https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/2015/how-rich-will-china-become.

- 23Population projections are taken from https://www.populationpyramid.net/.

- 24“The World in 2050: Will the Shift in Global Economic Power Continue?” PricewaterhouseCoopers, February 2015, https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/the-economy/assets/world-in-2050-february-2015.pdf.

- 25Jonathan Cheng, “China’s Economy Is Bouncing Back—And Gaining Ground on the U.S.,” Wall Street Journal, August 24, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/chinas-economy-is-bouncing-backand-gaining-ground-on-the-u-s-11598280917; Jonathan Cheng, “China Is the Only Major Economy to Report Economic Growth for 2020,” Wall Street Journal, January 18, 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-is-the-only-major-economy-to-report-economic-growth-for-2020-11610936187.

- 26James T. Areddy and Chao Deng, “China’s Slowing Growth Underlines Stress Facing Its Economy in 2020,” Wall Street Journal, January 17, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/chinas-economic-growth-slows-to-6-1-as-trade-and-business-confidence-suffer-11579236022.

- 27Whether to use PPP or MER as a measure of power depends on the purposes of the researcher. For measuring economic power as a proxy for realized or potential military power, PPP is superior. Less wealthy countries have lower labor costs, meaning China’s military spending can be more efficient per dollar spent. Also, MER is all but irrelevant for products built domestically, and China’s military expenditures rely on practically nothing that is imported from abroad. See Richard Connolly, “Russian Military Expenditure in Comparative Perspective: A Purchasing Power Parity Estimate,” CNA, October 2019, 20, https://www.cna.org/CNA_files/PDF/IOP-2019-U-021955-Final.pdf; Peter E. Robertson and Adrian Sin, “Measuring Hard Power: China’s Economic Growth and Military Capacity,” Defence and Peace Economics 28, no. 1 (2017): 91–111. Given that China’s military relies on domestic manpower and equipment built at home, PPP most accurately captures actual and potential Chinese military power. Using real GDP to compare military strength leads to absurd conclusions, like Russia being equal to the United Kingdom or France in military capabilities, despite the former being clearly superior in terms of manpower and access to advanced weapons systems. At the same time, MER is useful for understanding the potential for economic coercion abroad, as all international trade must go through international exchange markets.

- 28Michael Beckley, “China’s Century? Why America’s Edge Will Endure,” International Security 36, no. 3 (2012): 41–78.

- 29“Triadic Patent Families,” OECD, 2021, https://data.oecd.org/rd/triadic-patent-families.htm.

- 30“Gross Domestic Spending on R&D,” OECD, 2021, https://data.oecd.org/rd/gross-domestic-spending-on-r-d.htm.

- 31Noriaki Koshikawa, “China Passes U.S. as World’s Top Researcher, Showing Its R&D Might,” Nikkei Asia, August 8, 2020, https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Science/China-passes-US-as-world-s-top-researcher-showing-its-R-D-might.

- 32“The United States Invests More in Applied and Basic Research than Any Other Country but Invests Less in Experimental Development than China,” National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, December 2019, https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/2020/nsf20304/nsf20304.pdf.

- 33Eric A. Hanushek, “Economic Growth in Developing Countries: The Role of Human Capital,” Economics of Education Review 37 (2013): 204—212; Garett Jones, Hive Mind: How Your Nation’s IQ Matters so Much More than Your Own (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2015).

- 34“PISA 2018 Results,” OECD, accessed May 5, 2021, https://www.oecd.org/pisa/publications/pisa-2018-results.htm.

- 35“State Results: Massachusetts Science Scores,” NCES, accessed May 5, 2021, https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/pisa/pisa2015/pisa2015highlights_7.asp; Hayley Glatter, “Massachusetts Test Scores Top Nation’s School Districts Again,” Boston Magazine, https://www.bostonmagazine.com/education/2018/04/10/massachusetts-best-schools-naep.