October 16, 2025

Target Taiwan: One China and cross-strait stability

This explainer is part of the series "Target Taiwan"

Key points

- Washington should not move away from the One China policy, as doing so would increase the risk of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan.

- The U.S. policy of “strategic ambiguity” remains appropriate to the volatile cross-strait situation, but some policymakers overestimate the U.S. defense commitment to Taiwan.

- Recent administrations have taken steps to undermine the One China policy as part of an American strategy to counter China across the board, but this has had the deleterious effect of causing the U.S. and China to come to the brink of war over Taiwan.

- A realist approach to the Taiwan issue accepts and even seeks to strengthen both strategic ambiguity and the One China policy. In doing so, it increases the odds of negotiated solutions to disagreements while ensuring U.S. military forces are in a less vulnerable and volatile defense posture in the Asia-Pacific region.

The One China policy: a status quo that works

Previous papers in this series have explained why China could likely mount a successful invasion of Taiwan and why America and her allies couldn’t and/or wouldn’t do much to help. This paper will examine the One China policy, which has shaped the U.S. stance towards China for half a century and is now eroding. U.S. actions risk making a dangerous situation in East Asia worse—or even provoking the very war U.S. policies aim to deter.

The traditional U.S. approach is far from perfect, and a Chinese invasion could occur no matter how wise American policies are. But the status quo has succeeded for decades at achieving a delicate balance, providing Taiwan with arms while accepting mainland China’s goal of peaceful reunification with Taiwan and preventing moves toward independence that could spark a war.

U.S. presidents from Harry Truman onward have struggled with the issue, hoping to avoid war with Beijing, stabilize U.S.-China relations, and preserve Taiwan’s autonomy. To say this has been a difficult juggling act would be a vast understatement. It is likely that more than one U.S. president has contemplated nuclear use in a Taiwan scenario, and U.S. nuclear weapons were deployed to the island from the late 1950s until 1974 when they were removed as part of the warming trend in U.S.-China relations.1Details of these deployments are at Hans Kristenson, “Nukes in the Taiwan Crisis,” Federation of American Scientists, May 13, 2008, https://fas.org/publication/nukes-in-the-taiwan-crisis/.

During the rapprochement between Beijing and Washington in the 1970s, the issue of Taiwan formed the crucible upon which the new relationship was forged. Resolving the issues around Taiwan formed the foundation of U.S.-China relations, and this required significant compromises. Today, in a very different era, the volatile nature of Taiwan’s status once again threatens to pull China and the United States into the vortex of a catastrophic war. Americans must grapple fundamentally with both the history of the Taiwan issue and the concurrent evolution of Washington’s troubled One China policy.

A single explainer cannot hope to undo the entire Gordian Knot that Taiwan presents. Other Taiwan explainers in this series cover the changing military balance, both across the Strait and between U.S. and Chinese military forces. They also investigate the prospective roles of U.S. allies in a Taiwan scenario, as well as alternative defense strategies that Washington should adopt. Here, the focus of the discussion is on the diplomatic fine points of Taiwan’s past and future status. Such a focus shows that a U.S. move toward “strategic clarity”—that is, a formal, public commitment by the United States to defend Taiwan—would be a catastrophic mistake. To the contrary, U.S. adherence to the One China policy should actually be strengthened.

Why the One China policy is pivotal

The One China policy and strategic ambiguity are a policy framework developed half a century ago to achieve a pragmatic relationship between the United States and China. Before that, the relationship between Washington and Beijing was characterized by militarized rivalry, near-constant crises, and bloody warfare. However, in the half century since, U.S.-China relations have stabilized and both countries have benefited enormously. Yet today, some seek to overturn these foundations of the contemporary U.S.-China relationship, making the risk of superpower war much more likely.

The One China policy involves most fundamentally the recognition of the PRC as the sole representative government of China, while simultaneously de-recognizing the Republic of China (ROC), commonly known as Taiwan, and breaking almost all official ties with the government on Taiwan.2For more debate on the precise meaning of the One China policy, see Chong Ja Ian, “The Many ‘One Chinas’: Multiple Approaches to Taiwan and China,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, February 9, 2023, https://carnegieendowment.org/2023/02/09/many-one-chinas-multiple-approaches-to-taiwan-and-china-pub-89003. An important point raised in this piece is the idea that Washington’s One China policy is not the same as Beijing’s “One China Principle.” Washington agreed in the 1972 Shanghai Communique that “all Chinese on either side of the Taiwan Strait maintain there is but one China and that Taiwan is a part of China. The United States Government does not challenge that position.”3See the text of the “Shanghai Communique” at “Joint Statement Following Discussions With Leaders of the People’s Republic of China,” Office of the Historian, U.S. Department of State, February 27, 1972, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76v17/d203. That major change in policy—a master stroke in the annals of diplomacy—involved many difficult changes, not least the removal of substantial U.S. military bases on the island of Taiwan, as well as the abrogation of a defense treaty with Taiwan.

There were also numerous, smaller but still symbolic steps taken with the One China policy, including the downgrading of U.S. relations with the island to a non-official status. In order to cushion the geopolitical shock of these reforms, not least on the island itself, the U.S. government adopted a policy of strategic ambiguity with regard to the cross-strait relationship that both urged a peaceful solution to the Taiwan issue while also refusing to clarify whether or not the U.S. would deploy military power to defend Taiwan in case of a Chinese attack.4See, for example, Mark Episkopos, “New Taiwan Aid Signals Death Knell of ‘Strategic Ambiguity,’” Responsible Statecraft, September 7, 2023, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/china-taiwan-strategic-ambiguity/. These policies were an effort towards a more stable global balance of power, but were additionally meant to address key historical issues related to Asian nationalism that were simply too volatile to ignore. They also, crucially, allowed the U.S. to mend relations with the Chinese, splitting them away from the Soviet Union and providing them with incentives not to work with the Kremlin.

The One China policy represented an enormous success for U.S. foreign policy in the decades following the rapprochement with Beijing. Washington was able to conclude the Vietnam War and eventually to stabilize the volatile situations in both East Asia and South Asia, ushering in an era of unprecedented peace and prosperity. At the heart of the new prosperity was the dynamic engine of U.S.-China commercial growth that remains today one of the most important trading relationships in the world.

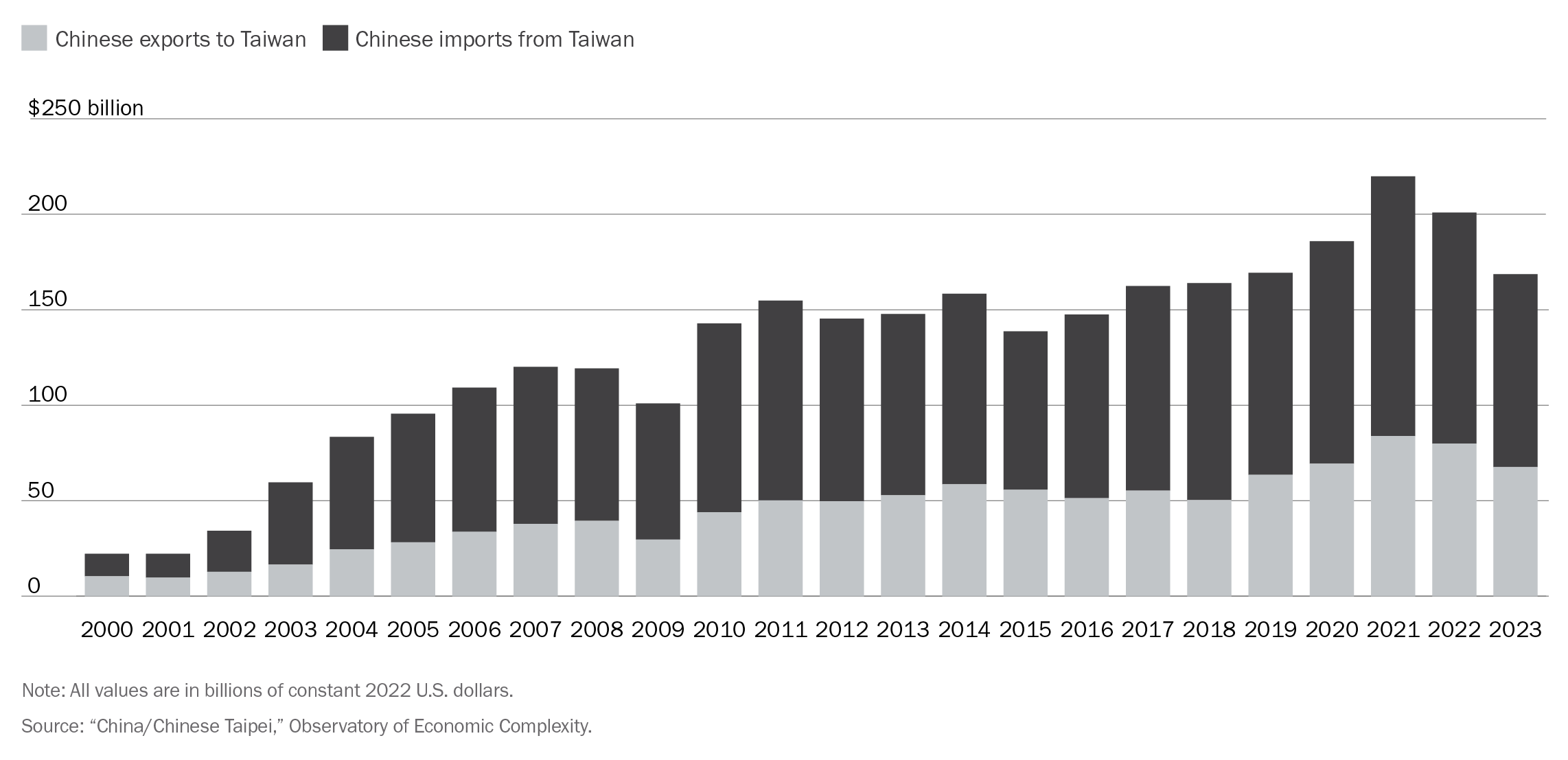

Notably, Taiwan businesses have been at the forefront of modernizing China’s economy over the last four decades. Considering the economic benefits of cross-strait trade, it’s also crucial to emphasize how devastating the losses would be for the U.S. and the entire world if a war occurred over the status of Taiwan. These losses could end up “dwarfing the blow from the war in Ukraine, Covid pandemic and Global Financial Crisis,” according to one analysis.5Jennifer Welch, Jenny Leonard, Maeva Cousin, Gerard DiPippo, and Tom Orlik, “Xi, Biden and the $10 Trillion Cost of War Over Taiwan,” Bloomberg, January 2024, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2024-01-09/if-china-invades-taiwan-it-would-cost-world-economy-10-trillion.

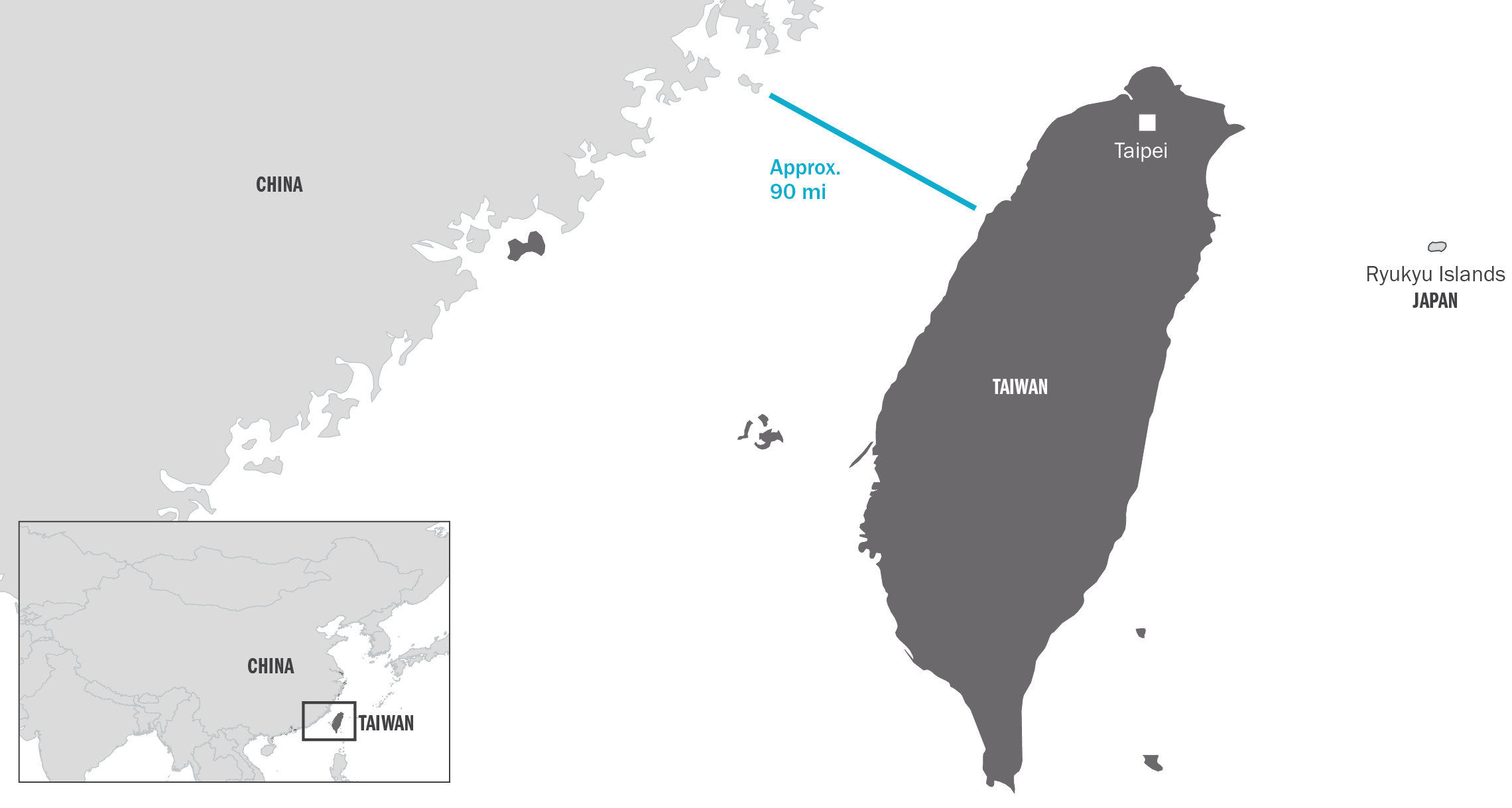

Proximity of Taiwan to China

On the diplomatic side, looking forward, U.S.-China cooperation will be critical to addressing key challenges in the twenty-first century, including dealing with regional conflicts, limiting nuclear proliferation, harnessing and controlling artificial intelligence, and addressing health, development, and climate change issues. Such cooperation would be impossible without the One China policy. The simple fact is that China matters much more across a wide spectrum of U.S. interests than Taiwan does.

All of these domains requiring a pragmatic relationship between Washington and Beijing have been put at risk by the militarized rivalry that has been developing as the One China policy and strategic ambiguity are undermined, whether by presidential rhetoric or congressional visits to Taiwan or new U.S. military deployments. Continuing and new U.S. military deployments proximate to China, whether in Okinawa, the Ryukyu Islands, or close to the Luzon Strait, are viewed as threatening to Beijing. China’s most basic problem with America’s Taiwan policy is that it amounts to maintaining a substantial base—for example, for intelligence collection—a mere 100 miles off of China’s shores (and much closer in the case of the offshore islands).

If it actually comes to a U.S.-China war, the conflict would likely entail major losses. Recent wargames project the probable sinking of multiple U.S. aircraft carriers, and it could get far worse, as revealed in DEFP’s in-depth examination of a U.S.-China war over Taiwan in the second paper in the “Target Taiwan” series.6See, for example, Cancian, Cancian, and Heginbotham, The First Battle of the Next War: Wargaming a Chinese Invasion of Taiwan, Center for Strategic and International Studies, January 9, 2023, 88, https://www.csis.org/analysis/first-battle-next-war-wargaming-chinese-invasion-taiwan; and Richard Bernstein, “The Scary War Game over Taiwan That the U.S. Loses Again and Again,” Real Clear Investigations, August 17, 2020, https://www.realclearinvestigations.com/articles/2020/08/17/the_scary_war_game_over_taiwan_that_the_us_loses_again_and_again_124836.html; Lyle Goldstein, “Target Taiwan: Challenges for a U.S. Intervention,” Defense Priorities, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/target-taiwan-challenges-for-a-us-intervention/. Moreover, there is a real risk of nuclear escalation even though Taiwan is not a U.S. ally. The U.S.-China nuclear rivalry is, first and foremost, driven by an erosion of the U.S. commitment to the One China policy and strategic ambiguity.

Abandoning the One China policy and adopting “strategic clarity” could lead to war in a number of ways. First, it could prompt leaders in Taipei to promote independence in a more brazen fashion, even causing them to declare independence, which would most certainly spark a war. Second, Washington would quite likely attempt to give the new policy teeth by deploying U.S. forces directly into Taiwan on a larger scale, prompting a Chinese attack. Finally, Beijing could simply conclude that the U.S. is foreclosing all possibilities for peaceful unification.

Rather than break the commitment that has maintained peace for so long, it should be the United States’ continued goal to discourage forceful reunification. A more aggressively anti-China policy fails to see that breaking with the United States’ past promises—namely the One China policy—actually constitutes a “bad friend policy,” placing the island in much greater danger. Fortunately, realistic policy alternatives do exist that can preserve Taiwan’s autonomy for the foreseeable future while simultaneously safeguarding U.S. national security and prosperity. This entails re-embracing the One China policy and strategic ambiguity while also relying on diplomatic tools to encourage cross-strait engagement.

The origin of the Taiwan issue in U.S.-China relations

Taiwan became a focal point for U.S.-Chinese tensions in the late 1940s as the Cold War with the Soviet Union and the Chinese Civil War both dramatically escalated in unison. The Chinese Civil War had actually begun two decades earlier in 1927, following the death of Sun Yatsen, a U.S.-educated leader revered by both the Chinese Nationalists and the Communists. The two sides battled intensively during the 1930s and then were reconciled for nearly a decade (1936–1945) during the common struggle against the invading Japanese. Yet that truce quickly fell apart after Japan’s surrender.

Washington made several attempts to get the Nationalists and the Communists to reconcile, including by sending General George Marshall to try to broker a settlement. U.S. President Harry Truman also authorized massive military and economic aid to the Nationalists to try to forestall a Communist victory.

Yet these efforts were to no avail and Communist victories in northern China in 1948 built momentum. According to a recent history of the Chinese Civil War, “Mao’s forces… had ‘completely wiped out’ seven divisions of Chiang [Kai-shek’s] men on Christmas Eve [1948]. …Above the Nationalist capital of Nanjing, the Communists had encircled Chiang’s frozen and starving recruits. …Chiang [gave] the order to withdraw his troops” to Taiwan.7Kevin Paraino, A Force So Swift: Mao, Truman, and the Birth of Modern China, 1949 (New York: Crown, 2017), 31–32. In dispatching his defeated forces to Taiwan, the Nationalist leader was echoing history. Three centuries earlier, during another period of civil war in China, remnants of the Ming Dynasty had retreated to the island in a beleaguered attempt to stave off defeat by the Manchus.8On this important chapter in Chinese history, see Tonio Andrade, Lost Colony: The Untold Story of China’s First Great Victory Over the West (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011).

However, the Nationalists were not popular on Taiwan, which had been colonized by Japan since the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95. Chinese rule of the island prior to Japanese annexation in 1895 goes back hundreds of years.9“U.S. Taiwan Relations in a New Era,” Council on Foreign Relations, Independent Task Force Report no. 81 (June 2023) 11, https://live-tfr-cdn.cfr.org/sites/default/files/2023-06/TFR81_U.S.-TaiwanRelationsNewEra_SinglePages_2023-06-05_Online.pdf. A bloody uprising against the Chinese Nationalists on Taiwan occurred in February 1947. It was brutally suppressed, leaving a scar on the island’s politics that persists to the present day.10Paul Mozur, “Taiwan Families Receive Goodbye Letters Decades After Executions,” New York Times, February 3, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/04/world/asia/taiwan-white-terror-executions.html.

Notably, President Truman made a speech in January 1950 stating that the United States recognized Taiwan as part of China after an apparent decision not to use American forces to defend the island against the planned Communist invasion.11“Harry S. Truman, ‘Statement on Formosa,’ January 5, 1950,” USC U.S.-China Institute, February 25, 2014, https://china.usc.edu/harry-s-truman-%E2%80%9Cstatement-formosa%E2%80%9D-january-5-1950; “U.S. Taiwan Relations…” Council on Foreign Relations, 13. That decision, which seems to have resulted mainly from disillusionment with the Chinese Nationalists, also affirmed President Franklin Roosevelt’s agreement in 1943 at the Cairo Conference of Allied leaders that Taiwan, after being occupied by Japan, should be returned to China.12“The Cairo Conference, 1943,” U.S. Department of State, accessed February 27, 2022, https://2001-2009.state.gov/r/pa/ho/time/wwii/107184.htm. The actions of these two American presidents—the first to consider the Taiwan issue—are vitally important because they signal that, in the absence of global political rivalry (i.e. the intensifying Cold War), American leaders appraising the historical record accepted that Taiwan was part of China. This acceptance undergirds the One China policy.

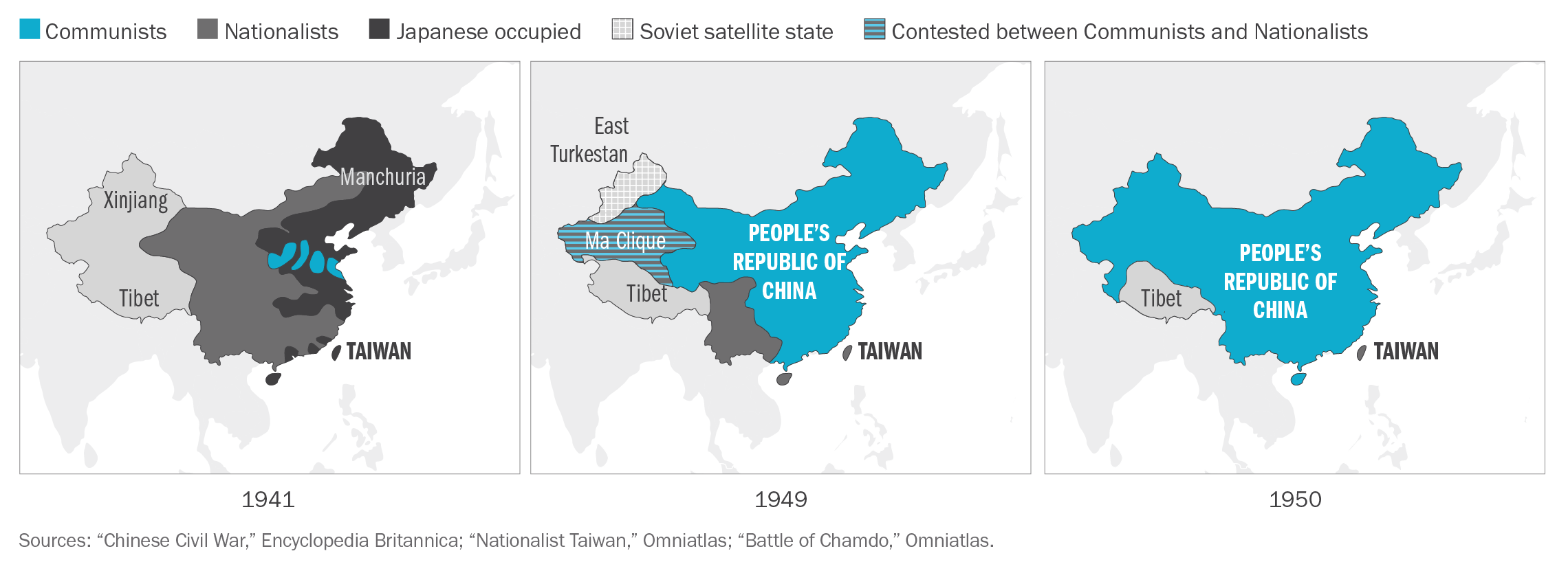

Political control of China (1941-1950)

Before the CCP consolidated control, mainland China was a patchwork of political entities. The CCP eventually defeated the Nationalists, who were exiled to Taiwan, and established the People’s Republic of China.

To be sure, Truman dramatically reversed the decision on Taiwan after the outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950 when he ordered the Seventh Fleet into the Taiwan Strait. He did this because the new and daunting circumstances of the Korean War required energizing the U.S. struggle in East Asia against communism and even preparing for global war. Two decades of intensive, militarized rivalry between Washington and Beijing followed: massive combat in Korea, covert aid to anti-communist insurgents in Tibet, and efforts to halt Chinese Communist infiltration into Southeast Asia, including in Vietnam.

For Taiwan, two major crises concerning offshore islands held by the Nationalists brought the United States and China to the brink of war in both 1954 and 1958, resulting in both a defense treaty between the Republic of China (ROC), as Taiwan is still officially known, and the United States, as well as the introduction of nuclear weapons for the island’s defense.13Hans Kristensen, “Nukes in the Taiwan Crisis,” Federation of American Scientists, May 13, 2008, https://fas.org/publication/nukes-in-the-taiwan-crisis/. During the early 1960s, U.S. President John Kennedy viewed China as a serious threat. He and his successor both considered employing Taiwan forces to strike at China’s nascent nuclear arsenal.14William Burr and Jeffrey T. Richelson, “Whether to ‘Strangle the Baby in the Cradle’: The United States and the Chinese Nuclear Program, 1960–64,” International Security 2001, 25 (3): 54–99. In effect, these decisions were taken in extremis—at a time when Washington was haunted by the prospect of global war and a potentially surging worldwide communist movement.

The Nixon breakthrough and the One China paradigm

National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger sat down with Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai in Beijing in 1971 to chart out a U.S.-China rapprochement that fundamentally altered the course of world politics, with no small impact on America’s Taiwan policy as well. Following President Richard Nixon’s public suggestion in October 1967 that the U.S. had to “come urgently to grips with the reality of China,” two significant peace overtures were made by Washington thereafter.15Chas W. Freeman, Jr., Interesting Times: China, America, and Shifting Balance of Prestige (Charlottesville, VA: Just World Books, 2012), 55. In November 1969, the United States quietly ended the Taiwan Strait patrol of the Seventh Fleet, while in February 1970 U.S. diplomats indicated during ongoing bilateral talks with the Chinese in Warsaw that it was the U.S. government’s “intention to reduce those military facilities which we now have on Taiwan as tensions in the area diminish.”16Freeman, 57–58.

Cornerstones of the One China policy

This was the bedrock of the U.S.-China compromise and the tradeoff that resulted in the One China policy: the United States would curtail its military presence on Taiwan while reserving the right to support the island so it could defend itself. The United States knew from the start this entailed reducing its commitments to Taiwan but it did so because it was a good deal and served vital interests of peace and stability in East Asia.

Two larger events were driving the U.S.-China rapprochement: the escalating Sino-Soviet conflict and the Vietnam War. In short, China sought peace and even reassurance from the U.S. so it could focus on the more immediate Soviet threat. Meanwhile, the U.S. badly needed help to extricate itself from the Vietnam quagmire.

As Kissinger explained, “My very presence in Beijing was a grievous blow to Hanoi.”17Henry Kissinger, On China (New York: Penguin, 2011), 248. But beyond symbolic gestures, it would become apparent that Beijing would not and probably could not deliver peace in Vietnam. Yet on Taiwan policy, there was a breakthrough. Kissinger himself concludes, “The secret trip [of July 1971] began the delicate process by which the United States has step by step accepted a one China concept, and China has been extremely flexible about the timing of its implementation.”18Kissinger, 250. Hinting at the difficulties ahead, Kissinger told President Nixon in October 1971 that “Zhou Enlai ‘has made it clear that there will be no normal relations until [the Taiwan] problem is resolved.’”19Rosemary Foot, “Prizes Won, Opportunities Lost: The U.S. Normalization of Relations with China, 1972-1979,” in William Kirby, Robert S Ross, and Gong Li (eds.), Normalization of U.S.-China Relations (London: Harvard University Press, 2005), 91. During that crucial month, the UN General Assembly voted to officially seat the Beijing representative, while the Taipei representative stormed out.20James Carter, “When the PRC Won the ‘China’ Seat at the UN,” SupChina, October 21, 2021, https://supchina.com/2020/10/21/when-the-prc-won-the-china-seat-at-the-un/.

The Shanghai Communique that resulted from President Nixon’s February 1972 visit is a comprehensive document that codifies the primary basis for America’s One China policy to the present day. It addresses a diversity of issues, including Vietnam, the Korean Peninsula, and Japan. However, the most memorable two paragraphs concern the fate of Taiwan and are divided between a Chinese and an American perspective. Beijing’s view outlined in the document is that “The Taiwan question is the crucial question obstructing the normalization [between the two countries]” and that China “firmly opposes any activities… [to] advocate that ‘the status of Taiwan remains to be determined.’”21“Joint Statement Following Discussions…”

The U.S. perspective offered in the document is reasonably clear: “The United States acknowledges that all Chinese on either side of the Taiwan Strait maintain there is but one China and that Taiwan is a part of China. The United States Government does not challenge that position.”22“Joint Statement Following Discussions…” Some Americans have subsequently tried to argue that “acknowledgement” is different than “acceptance.” Yet historian Rosemary Foot concludes that American “verbal acrobatics succeeded only in dizzying the spectators,” and further observes, “Taiwan’s status had indeed been tacitly decided in the PRC’s favor. As [Nixon] put it in his handwritten notes for his first private meeting with Zhou Enlai, the ‘status of Taiwan is determined.’”23Foot, 100.

By taking on the bureaucratically complex and ideologically fraught issue of Taiwan’s status in U.S. diplomacy, Kissinger and Nixon dramatically strengthened the U.S. position vis-à-vis the USSR. They placed the U.S.-China relationship on a positive trajectory with a workable framework within which future conflict could be avoided so long as the U.S. adhered to the One China policy.

Unfortunately, the “verbal gymnastics” continue to the present day, as some in Washington try to whittle away at the not-inconsiderable achievement of 1972.

Formal U.S.-China relations and the Taiwan relations act

After the Nixon visit, the difficulty of realizing a genuine improvement in the U.S.-China relationship proved no easy feat. Diplomatic and governmental contacts began in earnest, as liaison offices were established and trade flourished.24Freeman, 63. All U.S. combat forces and most U.S. military personnel had left Taiwan by the end of 1976, and by the end of 1978 most key members of Congress had visited Beijing.25Freeman, 63–64. Nevertheless, a major sticking point concerned the U.S. intention to keep selling arms to Taiwan. As Foot explains, “The argument ran that continuation of sales would help Taiwan continue to feel secure in an era when the Mutual Security Treaty had lapsed and would also help to dampen U.S. domestic criticism….”26Foot, 104. The issue of arms sales remained in bitter dispute all the way to the end of the negotiations in December 1978, with Deng Xiaoping offering no guarantee that the Taiwan issue could be resolved peacefully.27Foot, 113.

President Jimmy Carter’s determination to finish the process of normalization between Washington and Beijing was met with stalwart resistance at home. Senator Barry Goldwater took the administration to the Supreme Court over whether it had the power to abrogate the 1954 Mutual Defense Treaty between the United States and the Republic of China. The case was eventually dismissed, but Congress did pass the Taiwan Relations Act (TRA) in April 1979 to govern the new set of relationships. That act is mainly concerned with stabilizing the relationship with Taiwan and ensuring that the removal of diplomatic recognition would not upset U.S.-Taiwan relations, especially in the commercial sector.

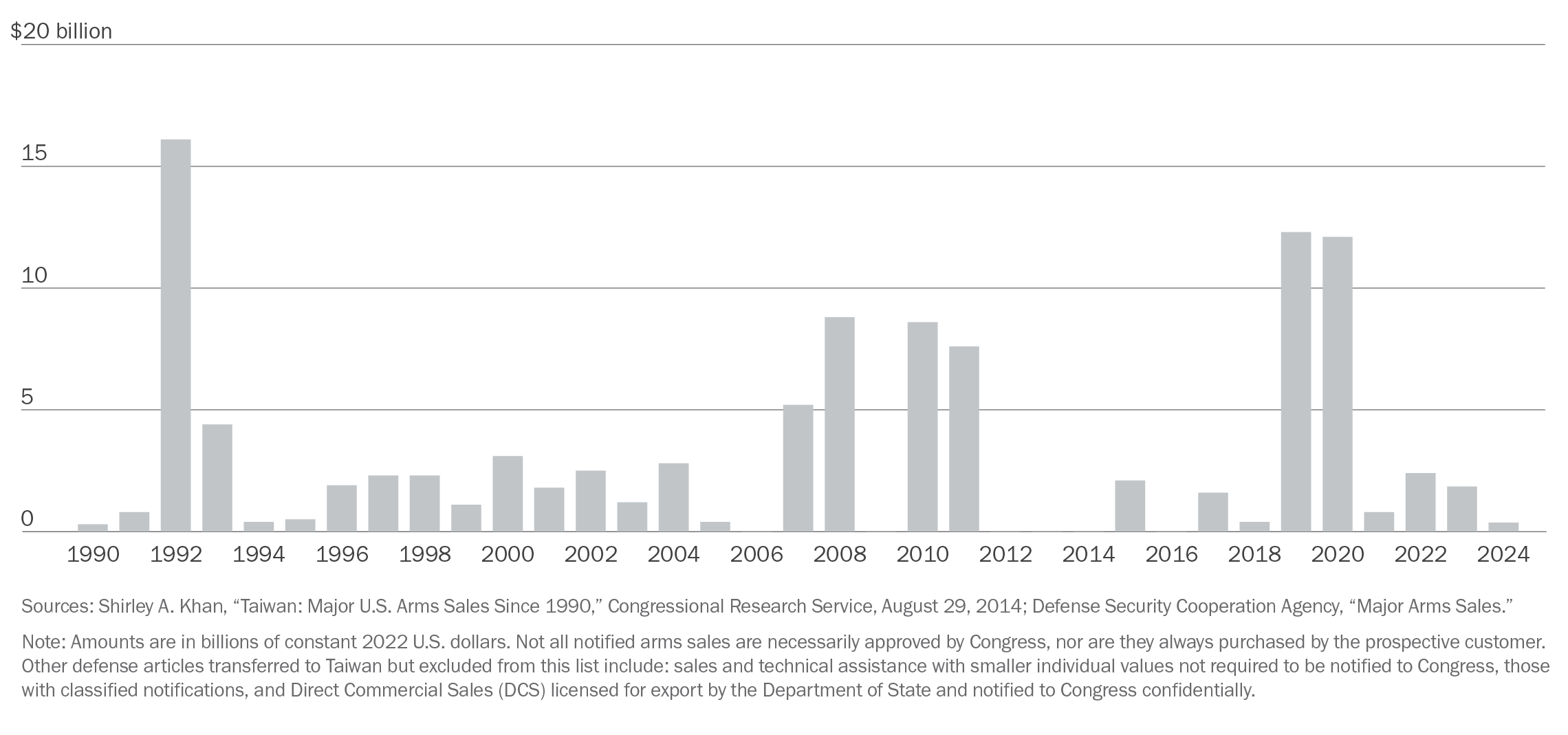

Major U.S. arms sales to Taiwan as notified to congress (1990-2024)

Despite a 1982 commitment by the U.S. to draw down arms sales to Taiwan, those sales have continued. Beijing has protested, viewing U.S. arms sales as facilitating Taiwan’s permanent separation from the mainland.

The TRA also set out two guiding principles for cross-strait relations, as least from the U.S. perspective. First, it set forth the expectation that the “the future of Taiwan will be determined by peaceful means” and that “any effort to determine the future of Taiwan by other than peaceful means” is considered “a threat to the peace and security of the Western Pacific area and of grave concern to the United States.” It goes on to state the United States “shall provide Taiwan with arms of a defensive character” and shall “maintain the capacity of the United States to resist any resort to force or other forms of coercion that would jeopardize the security, or social or economic system, of the people of Taiwan.”28“Taiwan Relations Act,” Public Law 96-8, April 10, 1979, https://www.congress.gov/96/statute/STATUTE-93/STATUTE-93-Pg14.pdf.

These are strong words, and they give ample fodder to those arguing that Taiwan is part of the American network of partners and allies in the Asia-Pacific. Obviously much hinges on a president’s interpretation of the words “grave concern” in such a hypothetical situation. However, it is worth underlining here that the TRA does not guarantee the U.S. will come to the defense of Taiwan. Even the Council on Foreign Relations, which seems to support U.S. defense of Taiwan, concedes that “the TRA does not commit the United States to come to Taiwan’s defense….”29“U.S. Taiwan Relations…” 17. The actual mutual defense treaty did formerly exist between the U.S. and Taiwan, but this was abrogated.

In hindsight, the TRA played a positive role in cushioning the impact of Washington’s abrupt switching of diplomatic recognition from Taipei to Beijing. In effect, it gave Taiwan and the world time to readjust to the new geopolitical realities. The TRA does not detract from the principles enshrined in creating a firm One China structure for stable U.S.-China peace, especially given the cultural and geographical proximity of Taiwan to the mainland, as well as the imperative to prevent great power conflict in the era of nuclear weapons.

The TRA also shows stark disagreement within the U.S. about how to proceed on the Taiwan issue. The executive branch and the legislative have gone in quite different directions. While it is common to interpret this as a kind of balance or dichotomy at the heart of America’s Taiwan policy, there has also been a steady and consistent erosion of the One China policy that has predictably created tensions between the United States and China where none need exist.

Growing discord with the One China policy

During the 1980s, the One China policy triggered significant discord, as America’s approach to Taiwan was pulled in different directions. In the so-called Third Joint Communique made with China in August 1982, the U.S. pledged that “it intends gradually to reduce its sale of arms to Taiwan, leading, over a period of time, to a final resolution.”30“Joint Communique of the United States of America and the People’s Republic of China,” Taiwan Documents Project, August 17, 1982, http://www.taiwandocuments.org/communique03.htm. However, it is now known that Washington simultaneously proffered the-then classified Six Assurances to Taipei in order to reassure authorities on Taiwan that no date had been reached on ending arms sales and that the U.S. would not mediate across the Strait or apply pressure to Taipei to enter negotiations with Beijing.31“U.S. Taiwan Relations…” 18. These promises were likely classified because, overall, cooperation between Beijing and Washington proved robust in this period, reaching into such areas as intelligence gathering and even military-technical cooperation.

By the end of the Cold War, however, the glue that had kept China and the U.S. together seemed weak. In particular, the Tiananmen Square Massacre in 1989 colored America’s relations with China. While Chinese and Taiwan representatives did meet in Singapore in November 1992 to reach some common understandings, cross-strait tensions rose once again. Two major causes of the new inflammation were, on the one hand, Taiwan’s evolution away from Chinese culture and its government’s growing distance from mainland China—reflecting generational change on the island—and, on the other hand, Beijing beginning to rapidly modernize its previously backward armed forces by taking advantage of fire-sale prices for weapons and related expertise in the former USSR.32See, for example, Sergei Nikolaevich Goncharov [谢尔盖 尼科拉耶维奇 冈恰罗夫], “The Su-27 and the Beginnings of China-Russia Military Technical Cooperation” [苏27-中俄军事技术合作的开端], Modern Ships [现代舰船], March 2017, 77; and also Alexander Korolev, China-Russia Strategic Alignment in International Politics (Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam Press, 2022), 73–75.

Washington responded with major arms sales to Taiwan. These tensions culminated in the 1995–96 Taiwan Strait Crisis that involved the PLA firing ballistic missiles near Taiwan’s ports in a demonstration of force, while the U.S. deployed multiple aircraft carrier groups to the proximate waters of Taiwan for deterrence purposes. The crisis, while not especially dangerous in terms of brinkmanship since Washington seemed to decisively hold the military advantage, did prove eye-opening for both sides. For the U.S., there was a growing recognition that China might one day emerge as a military rival. For China, triggered by U.S. arms sales and deployments near Taiwan, there arose a new imperative to match U.S. military might, at least with respect to a Taiwan scenario, which became embedded in Beijing’s national security planning apparatus.33Richard Bush, Untying the Knot: Marking Peace in the Taiwan Strait (Washington, DC: Brookings, 2005), 116. It is not a coincidence that the PLA Navy’s striking power increased substantially in the decade following the crisis, making U.S. naval operations in and around the Strait far more perilous.34See, for example, Michael A. McDevitt, China as a Twenty-First Century Naval Power (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2020), 22–27.

The once-steady One China policy had begun to erode and tensions over Taiwan only continued to grow. In February 2000, according to Taiwan expert Richard Bush, Beijing issued a new white paper on Taiwan that elaborated on three “ifs,” any of which would trigger Beijing’s resort to force across the Strait. The first condition concerned if Taipei were to change its name from “Republic of China,” presumably to “Republic of Taiwan.” The second condition concerned a foreign “invasion or occupation,” which would cover the presence of foreign soldiers on the island. The third condition was perhaps most disturbing due to its ambiguity, as Beijing noted it might resort to force if Taiwan refused to negotiate with China concerning the island’s status.35This whole paragraph draws from Bush, Untying the Knot, 120. For the original Chinese document, see “White Paper—The One-China Principle and the Taiwan Issue,” Taiwan Affairs Office of the China State Council, accessed via Taiwan Documents Project, February 21, 2000, http://www.taiwandocuments.org/white.htm.

The 9/11 attacks, however, quite suddenly convinced Washington, for a time at least, that the really important national security issues lay in the Greater Middle East. U.S.-China relations briefly improved and President George W. Bush openly criticized Taipei in December 2003 for trying “unilaterally to change the status quo, which we oppose.”36Bush, 251. While this was a commendable defense of the One China policy, it may also be viewed cynically as Washington elevating the War on Terror, wherein it required Beijing’s support, including at the United Nations.37On the Bush administration’s warming of relations with Beijing after the 9/11 attacks, see Pak K. Lee, “George W. Bush’s post-9/11 East Asia policy: enabling China’s contemporary assertiveness,” International Politics 61 (2024), https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-023-00486-0, 587–611. Yet it showed the United States still understood what it was doing—it knew it could pacify Beijing when necessary and provoke Beijing if it so chose.

Taiwan’s leader at the time, Chen Shuibian, known as something of a provocateur, responded caustically a few days later: “The U.S. waged a war in Iraq in order to give the Iraqi people democracy. …Why does the U.S. restrict our rights to pursue democracy?”38Bush, 252. Chen’s comment illustrated how U.S. policy on Taiwan sometimes contradicted the overall preference to promote democracy. Confronting Chen’s brazen support for independence, Beijing increased pressure by passing an “Anti-Secession Law” in March 2005, which, among other measures, stated that China would resort to “non-peaceful” means if “incidents entailing Taiwan’s secession from China should occur” or the “possibilities for a peaceful reunification should be completely exhausted.”39“Anti-Secession Law,” Interpret China, Center for Strategic and International Studies, March 14, 2005, https://interpret.csis.org/translations/anti-secession-law/. Underlying the seriousness of the matter, the law stated that if China resorted to force, it would endeavor not to harm Taiwanese civilians and their property.

During the decade before the passage of the “Anti-Secession Law,” it is noteworthy that Washington had taken several steps to undermine its previously strict interpretation of the One China policy, including policies related to the American Institute in Taiwan (AIT)—a non-governmental organization formed to handle the unofficial relations between Washington and Taipei.40The home website of the AIT is https://www.ait.org.tw/. It is noteworthy that this website contains no background or summary explanations for how the institute functions, suggesting its enigmatic status. Thus, in 1994, AIT personnel first began to attend meetings in Taiwan’s government buildings.41“U.S. Taiwan Relations…” 19. Also at that time, it was decided that U.S. cabinet-level officials could once again visit the island. A decade later, U.S. officials began to serve at AIT without resigning from the Foreign Service.42“U.S. Taiwan Relations…” 22. In addition, the first American uniformed armed forces personnel returned to Taiwan for posting at AIT in 2005.43“U.S. Confirms Active Military Personnel Posted at AIT since 2005,” Taipei Trade Office in the Federal Republic of Nigeria, April 4, 2019, https://www.roctaiwan.org/ng_en/post/2656.html#:~:text=Taipei%2C%20April%203%20(CNA),in%20Neihu%20on%20May%206. Unfortunately, this steady watering down of the One China policy—a form of “salami-slicing”—predictably planted the seeds for tensions that are now fully emergent in our own time.

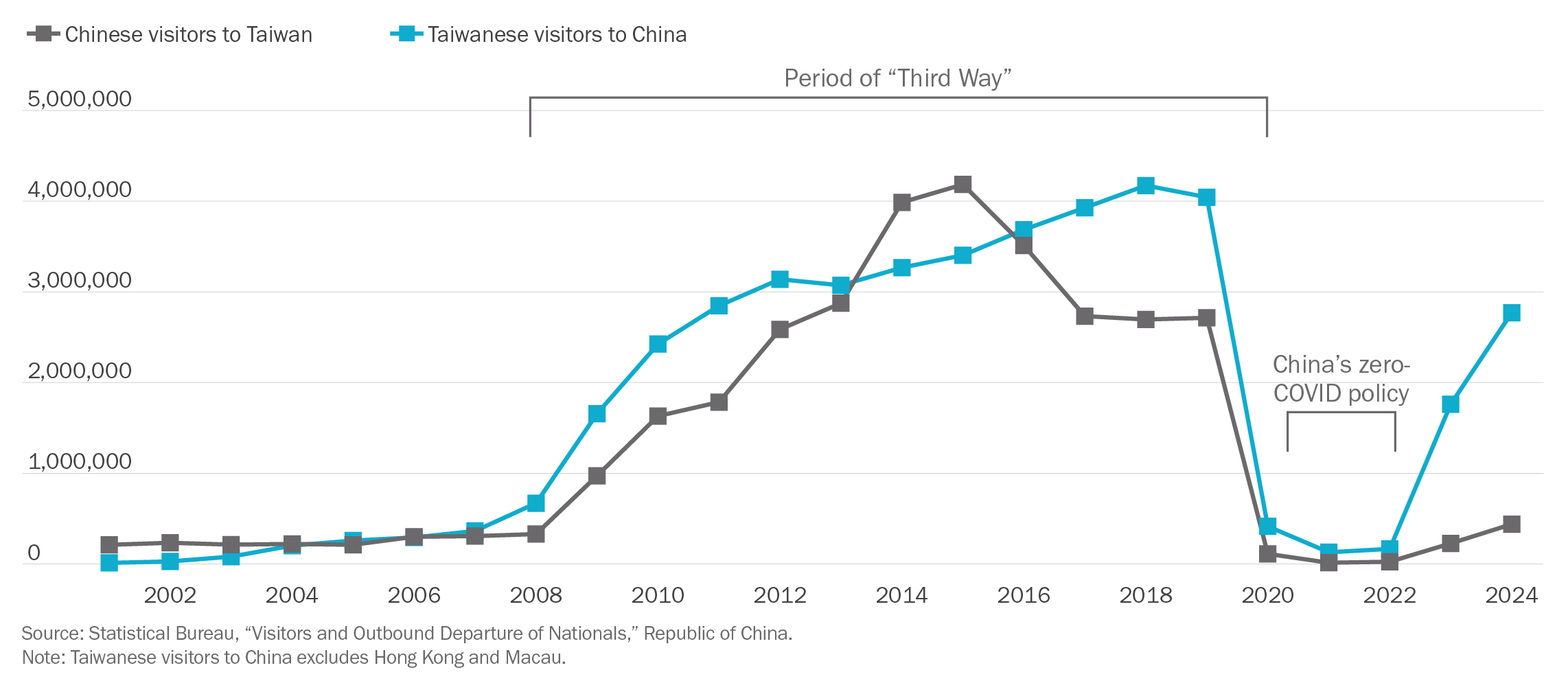

Nonetheless, the late aughts brought an almost unprecedented calm to cross-strait relations. That development can be put down chiefly to the new approach adopted by Chen’s successor, Ma Ying-jeou, who was elected president of Taiwan in 2008 and immediately set about transforming the cross-strait relationship by creating direct postal, transport, and trade linkages between Taiwan and the mainland. While Washington was largely distracted by other issues, most stemming from intractable situations in the Middle East, cross-strait relations enjoyed a period of renaissance, which is worth briefly exploring.

High watermark in cross-strait relations: Xi-Ma meeting in 2015

The period of calm in the China-Taiwan relationship reached its culmination in November 2015, when the two respective leaderships held a historic first face-to-face meeting in Singapore.

Even though no major agreements were reached, the two leaders could be said to have achieved some breakthroughs, since they had already set in motion economic and social linkages in the form of the “three links” that opened up direct travel for the first time, as well as a major cross-strait trade and investment agreement.44See, for example, Yasuhiro Matsuda, “Cross-strait Relations under the Ma Ying-jeou administration: From Economic to Political Dependence?” Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies no. 2 (2015), 3–35. A flood of Chinese tourists visiting Taiwan boosted the island’s economy.45“Chinese Tourists Boost Taiwan’s Economy,” Washington Post, August 30, 2012, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/chinese-tourists-boost-taiwan-economy/2012/08/30/99d36e98-f2ba-11e1-a612-3cfc842a6d89_story.html. The meeting not only illustrated the wide scope for cross-strait cooperative endeavors, but also the tantalizing possibility that Taiwan could be both part of China and retain a high degree of autonomy. Moreover, this period powerfully demonstrated how positive cross-strait relations could support U.S. national interests.

Mainland China and Taiwan bilateral trade volume (2000-2023)

Trade between China and Taiwan has grown significantly since 2000. Despite an increase in geopolitical tensions, China has become one of the top importers of Taiwanese goods while Taiwan remains economically reliant on exports to China.

Ma Ying-jeou had been elected Taiwan’s president promising to reduce tensions with China, and he proved good to his word.46John Franklin Copper, Taiwan: Nation-state or Province? (New York: Routledge, 2020), 266. He achieved this largely by avoiding moves toward independence, or those Beijing might perceive that way, and aggressively pursuing diplomatic progress with Beijing. Despite these considerable achievements, his KMT party lost the subsequent election, effectively reversing the positive trend in cross-strait relations. As Taiwan expert John Copper explains, “Some U.S. officials felt that Ma was too pro-China. Arguably, the United States did not want Taiwan’s unification with China – not withstanding America’s one-China policy.”47Copper, 267. In fact, the lowering of tensions across the Taiwan Strait that occurred during this period benefited U.S. national interests, since Washington was able to focus on other, more pressing matters.

A new paradigm under the first Trump administration

After more than a decade of calm due in no small part to the policies of Ma, the years since 2016 have seen a move toward the opposite extreme. The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) of Taiwan has generally been more hostile to Beijing, so the trend is not surprising, but Tsai Ying-wen proved to be relatively moderate. Nevertheless, China showed its displeasure with the direction of Tsai’s government by suspending all official ties with Taiwan in June 2016 because “the island’s new leader would not endorse the idea of a single Chinese nation.”48Javier Hernandez, “China Suspends Diplomatic Contact with Taiwan,” New York Times, June 25, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/26/world/asia/china-suspends-diplomatic-contact-with-taiwan.html.

Escalating tensions over Taiwan have come about for two main reasons. First, China’s power has been increasing rapidly, including its military capabilities, raising the dark prospect of a military solution to the Taiwan issue. To be sure, having the capabilities to invade does not necessarily mean Beijing has the intent. Myriad political factors could impact Chinese intentions, and some of these are discussed toward the end of this paper. But growing power does seem to have brought growing expectations among China’s ruling elites for eventual unification prompted by the improving cross-strait ties under Ma.

U.S. policy is also an important factor in current tensions. In particular, the first Trump administration moved over time toward a position at odds with the One China policy that had underpinned the calm of the prior era, prompting a series of warnings and Chinese military exercises in and around Chinese waters that have grown in frequency and scale.

The Trump administration’s approach to the Taiwan issue was unorthodox from the start. Even before taking office, the new president-elect accepted a phone call from Tsai Ying-wen, prompting a series of harsh rebukes from Beijing, since this was viewed as a major breach of the traditional One China policy, which abjures nearly all official contacts between Washington and Taipei, especially at the most senior level.49This is why the U.S. does not maintain an “embassy” in Taipei, but rather has the AIT—an unofficial channel. Similarly, Taiwan military officers attend U.S. military schools regularly, but they are forbidden from donning uniforms since they are not official representatives. The Taiwan Strait Crisis of 1995–1996 occurred, in large measure, as a result of disputed interpretations between Beijing and Washington about what constituted an acceptable level of contact between Taiwan officials and the United States. For another example of common disputes about these ties, see “Chinese Embassy Spokesman: China Opposed to Official Contacts or Exchanges between U.S. and Taiwan in Any Form,” Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the United States of America, October 23, 2003, http://us.china-embassy.gov.cn/eng./zt/twwt/200310/t20031023_4912227.htm. China issued numerous warnings, even parading its new mobile ICBMs on television. In the rather unmistakable tone of a nuclear threat, a piece in the Chinese official military press warned, “China’s nuclear capability should be so strong that no country would dare launch a military showdown with China under any circumstance.”50Lyle Goldstein, “China Rattles the Nuclear Saber,” National Interest, February 22, 2017, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/china-rattles-the-nuclear-saber-19536. The piece further notes, “The US has not paid enough respect to China’s military. Senior US officials of the Asia-Pacific command frequently show their intention to flex their muscles with arrogance. The Trump team also took a flippant attitude toward China’s core interests after Trump’s election win.”

Also in December 2016, the Chinese Navy seized a U.S. Navy drone, which some analysts saw as a direct reaction to Trump’s call with Tsai.51“China Seizes an Underwater Drone and Makes a Point to Donald Trump,” Economist, December 24, 2016, https://www.economist.com/china/2016/12/24/china-seizes-an-underwater-drone-and-sends-a-signal-to-donald-trump. With the kind of whiplash that would characterize much of the first Trump administration’s policy toward China, President Trump made a phone call to Xi in early February 2017 in which he endorsed the One China policy.52Mark Landler and Michael Forsyth, “Trump Tells Xi Jinping U.S. Will Honor ‘One China’ Policy,’” New York Times, February 9, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/09/world/asia/donald-trump-china-xi-jinping-letter.html.

Yet the cordial relationship was not to last. A speech given by Vice President Mike Pence during October of that year signaled an across-the-board assault on the U.S.-China relationship. Pence accused China of “meddling in America’s democracy” and promised responses such as “modernizing our nuclear arsenal.”53“Remarks by Vice President Pence on the Administration’s Policy Toward China,” White House, October 4, 2018, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-vice-president-pence-administrations-policy-toward-china/. Pence said that “while our administration will continue to respect our One China Policy, as reflected in the three joint communiqués and the Taiwan Relations Act, America will always believe that Taiwan’s embrace of democracy shows a better path for all the Chinese people.”54“Remarks by Vice President Pence…” He also fixated on the Beijing-Taipei rivalry for diplomatic recognition, noting, “And since last year alone, the Chinese Communist Party has convinced three Latin American nations to sever ties with Taipei and recognize Beijing. These actions threaten the stability of the Taiwan Strait, and the United States of America condemns these actions.”55“Remarks by Vice President Pence…”

Other Trump administration steps away from the One China policy included an expensive upgrade of the U.S. diplomatic facility (or de facto embassy) in Taipei and more aggressive steps to counter China’s diplomatic attempts to woo countries away from recognizing Beijing (versus Taipei) as the only representative of China. Thus, when the then-president of El Salvador switched diplomatic recognition to Beijing, following almost all other countries in the world including the U.S., the Trump administration responded with harsh words, saying Salvador Sánchez Cerén had affected “the economic health and security of the entire Americas region.”56Gardiner Harris, “U.S. Weighed Penalizing El Salvador Over Support for China, Then Backed Off,” New York Times, September 29, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/29/world/americas/trump-china-taiwan-el-salvador.html. The Trump administration additionally augmented the number of Taiwan Strait transits made by U.S. Navy warships.57Caitlin Doornbos, “Navy Ties Record with its 12th Transit through the Taiwan Strait This Year,” Stars and Stripes, December 19, 2020, https://www.stripes.com/theaters/asia_pacific/navy-ties-record-with-its-12th-transit-through-the-taiwan-strait-this-year-1.655831. It also increased the number of senior U.S. officials visiting the island and sold Taiwan a huge quantity of weaponry, setting a record in 2019 of $10.72 billion in sales.58“Factbox: Recent Taiwan Visits by Top U.S. Officials,” Reuters, January 7, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-taiwan-usa-diplomacy-factbox/factbox-recent-taiwan-visits-by-top-u-s-officials-idUSKBN29C16B; “Notified Taiwan Arms Sales, 1990-2020,” Taiwan Defense & National Security, December 7, 2020, https://www.ustaiwandefense.com/taiwan-arms-sales-notified-to-congress-1990-2020/.

Over the last several years, it has become routine for Chinese leaders and commentators to threaten Taiwan’s existence. In 2019, for example, Xi Jinping said unification was “an inevitable requirement for the great rejuvenation of the Chinese people.” He also said Beijing “reserves the option of taking all necessary measures” against external forces that interfere with Chinese reunification.59“Xi Jinping says Taiwan ‘must and will be’ reunited with China,” BBC News, January 2, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-46733174. Additionally, in May 2020, a mainland specialist on Taiwan noted, “In fact, with the rapid growth of the mainland’s comprehensive strength, [China] has the conditions and ability to solve the Taiwan issue in a physical way.”60Liu Guoshen [刘国深], “‘Republic of China on Taiwan’ Is a Trick for ‘Seeking Independence’ that Challenges the Bottom Line” [‘中华民国台湾’是挑战底线的’谋独’把戏], Global Times [环球时报], May 26, 2020, https://opinion.huanqiu.com/article/3yPDMr46bll. Likewise, the PLA has been exercising with the intent to “hone and enhance the ability to safeguard national sovereignty, security and territorial integrity.”61“The Eastern Theater Command Organized a Joint Naval and Air Force Exercise in the Southeastern Waters of Taiwan Island” [东部战区在台岛东南部海域组织海空兵力联合演练], PLA Daily [解放军报], February 11, 2022, http://www.81.cn/jfjbmap/content/2020-02/11/content_253811.htm. The message should be clear: whittle away at the One China policy and China will respond in kind.

The Hong Kong crisis and its meaning for Taiwan

Another major aggravating factor feeding cross-strait tensions during the first Trump administration was the Hong Kong Crisis of 2019–2020. This was a very important event for Taiwan because it might have hinted at the island’s future if either Washington or Taipei were to push too hard to break with the compromises set in place in the 1970s.

The Hong Kong Crisis erupted in early 2019 over extradition laws, which could have allowed Hong Kong citizens to be sent to the mainland for trial. Massive protests rocked the city for more than a year, causing some violence, but also substantial property damage and disruptions. A May 2020 national security law enacted by Beijing pushed the Hong Kong government to take much more aggressive steps to curtail the protests and democracy activists in the city. Since that time, major publications in Hong Kong have been shut down and hundreds of protesters have been jailed.

The protests roiling Hong Kong, followed by the crackdown, had a major impact on both Taiwan and China’s calculations with respect to the cross-strait relationship. In Taiwan, the population reacted with sympathy for Hong Kong and revulsion at the changes. They saw Hong Kong as having substantial autonomy since its reunification with the mainland in 1997, but that autonomy seemed to dissipate quickly when Beijing lost patience with the unrest. It is worth noting that arrested protesters convicted under the new law have, so far, not been given extreme sentences.62“Hong Kong: First Person Jailed under Security Law Given Nine Years,” BBC News, July 30, 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-58022072. Nor does the city seem to have suffered serious economic damage.63“Hong Kong Economy Grows 5.4% Year on Year in Third Quarter,” Reuters, November 21, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/hongkong-economy-gdp/update-1-hong-kong-economy-grows-5-4-year-on-year-in-third-quarter-idUSL1N2S30IK.

Yet the impact on Taiwan’s political scene was clear. An analysis by the National Bureau of Asia Research (NBR) explains, “As the pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong evolved into violent confrontations, President Tsai [of Taiwan] began to rise in the polls.”64Rachel Bernstein interview of Christina Lai, “The Impact of the Hong Kong Protests on the Election in Taiwan,” National Bureau of Asian Research, January 23, 2020, https://www.nbr.org/publication/the-impact-of-the-hong-kong-protests-on-the-election-in-taiwan/. This turnaround was remarkable since Tsai’s party was in bad shape in early 2019.65David G. Brown and Kyle Churchman, “DPP Suffers Defeat,” Comparative Connections 20, no. 3 (January 2019), https://cc.pacforum.org/2019/01/dpp-suffers-defeat/. Given Tsai’s fraught relationship with Beijing, her strong electoral victory in early 2020 was bound to increase tensions across the Strait.

But the even more important impact of the crisis may have been on the Chinese leadership. Beijing had long assumed that the “one country, two systems” formula developed by Deng Xiaoping could apply equally to both Hong Kong and Taiwan. If the Hong Kong crisis showed that the compromise was unworkable, it portended a very dark future for Taiwan. In other words, Chinese leadership after 2020 may be less interested in compromising with Taipei and more inclined toward the use of force.

Despite troubling developments in Hong Kong, it is nevertheless vital to step back and consider the impact of the crisis on U.S. national security. While both the U.S. Congress and the first Trump administration indicated major frustration with these developments, there has been no suggestion that the U.S. and its allies would or could intervene militarily to try to protect Hong Kong’s autonomy. Nor has it been suggested that China’s approach to Hong Kong represents a direct threat to U.S. national security.66Admiral John Aquilino, commander of INDO-PACOM, did mention Hong Kong as an indication that China might be more aggressive toward Taiwan, but he did not say that actions in Hong Kong directly threaten U.S. national security. Brad Lendon, “Chinese Threat to Taiwan ‘Closer to Us Than Most Think,’ Top US Admiral Says,” CNN, March 24, 2021, https://www.cnn.com/2021/03/24/asia/indo-pacific-commander-aquilino-hearing-taiwan-intl-hnk-ml/index.html. Washington has reacted to developments in Hong Kong by using economic instruments only and by avoiding military threats and escalation—a prudent decision.

A similar approach is advisable if Beijing opts to use force in a Taiwan scenario, because the military situation is increasingly unfavorable, as discussed in detail in explainers 1 and 2 of this series. Yet the main lesson of the Hong Kong protests for Taiwan is that Taiwanese leaders should not push too far in the direction of independence. Western leaders may have played a deleterious role in this process by raising expectations that they might have substantial leverage against Beijing with respect to Hong Kong. Such hopes proved illusory in the final analysis. Similarly, Taiwan and her advocates should choose the wiser course of moderation that will likely go much further in protecting the island’s autonomy.

The Biden administration hardline approach to Taiwan

To avoid the fate of Hong Kong’s curtailed autonomy, and particularly a catastrophic war between two nuclear-armed superpowers, it is imperative for Washington to adhere to the One China policy and maintain strategic ambiguity.

Unfortunately, the Biden administration seems to have moved in the opposite direction. The administration’s relations with China got off to a rocky start with the very tense bilateral meeting that took place in Anchorage in March 2021.67Barbara Plett-Usher, “US and China Trade Angry Words at High-Level Alaska Talks,” BBC News, March 19, 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-56452471. Later, in August of that year, President Joe Biden seemed to mistakenly blur U.S. defense commitments with a surprising statement: “We made a sacred commitment to Article 5 that if in fact anyone were to invade or take action against our NATO allies, we would respond. Same with Japan, same with South Korea, same with—Taiwan.”68David Brumstrom, “U.S. position on Taiwan unchanged despite Biden comment – official,” Reuters, August 20, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/us-position-taiwan-unchanged-despite-biden-comment-official-2021-08-19/.

This would not be the last time this American president, whether purposefully or in a state of confusion, explored the maximalist boundaries of America’s security commitments concerning Taiwan. On the other hand, it’s worth noting that similar comments from Biden have repeatedly been “walked back” by administration officials, suggesting ample support for more cautious approaches within the administration’s inner circle of national security experts.69See, for example, Ashley Parker and Tyler Pager, “The White House Keeps Walking Back Biden’s Remarks,” Washington Post, May 24, 2002, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/05/24/biden-walk-back-remarks/.

Nevertheless, one of the Biden administration’s top China experts, Dr. Ely Ratner, assistant secretary of defense for Indo-Pacific affairs, seemed at the end of 2021 to take another risk-laden step toward ratcheting up tensions in the Taiwan Strait by officially outlining a strategic rationale, seemingly for the first time since 1972, for American defense of Taiwan. Ratner stated, “Taiwan is located at a critical node within the first island chain, anchoring a network of U.S. allies and partners… [and thus] is critical to the region’s security and critical to the defense of vital U.S. interests in the Indo-Pacific.”70“Statement By Dr. Ely Ratner, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Indo-Pacific Security Affairs, Office of the Secretary of Defense Before the 117th Congress Committee on Foreign Relations United States Senate,” December 8, 2021, https://www.foreign.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/120821_Ratner_Testimony1.pdf.

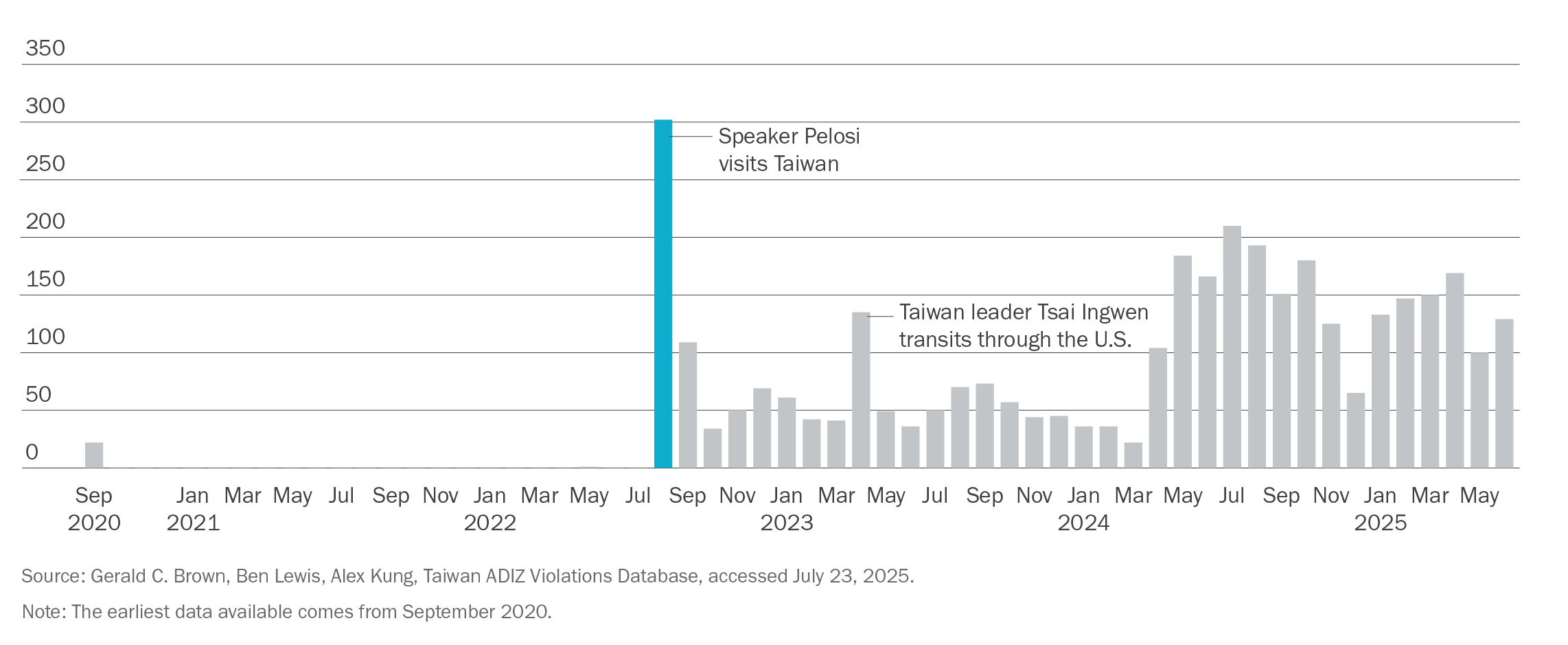

Taiwan Strait median line crossings by Chinese military aircraft (September 2020-June 2025)

Since the August 2022 visit by Nancy Pelosi, China has sought to create a new normal in which they don’t recognize the median line in the Taiwan Strait and claim Taiwan’s airspace as their own.

Tensions in U.S.-China relations flared up in August 2022 when U.S. House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi made a visit to Taiwan. During Beijing’s robust show of force on that occasion, Chinese missiles actually arced directly over the island, while PLA air and naval forces made dramatic demonstrations, including initiating operations to the east of the island that seemed to simulate a blockade. A record number of Chinese aircraft flew proximate to Taiwan in December 2022.71Amy Chang Chien and Chang Che, “With Record Military Incursions, China Warns Taiwan and the U.S.,” New York Times, December 26, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/26/world/asia/china-taiwan-jets.html. The increased tensions demonstrated a dangerous new normal in which PLA units seemed to regularly ignore the mid-line across the Taiwan Strait that had previously served as a kind of boundary line.

Speaker Pelosi’s visit seems to have made Taiwan’s security situation even more precarious. One reason is that with PLA aircraft now regularly crossing the mid-line of the Strait and PLA units operating on all sides of Taiwan, it is easier for China to mask an attack and achieve surprise. Such regular operations not only more fully reveal Taiwan’s defenses, but also lead to fatigue and readiness issues for Taiwanese forces.72Meera Suresh, “’Fatigue Problem’: China Is Winning Its Attrition Tactics as Taiwan’s Most Advanced Fighter Jet Crashes,” International Business Times, January 13, 2022, https://www.ibtimes.com/fatigue-problem-china-winning-its-attrition-tactics-taiwans-most-advanced-fighter-jet-3374828. Moreover, when U.S. officials go to Taiwan, it antagonizes and provokes China, making the situation worse. These visits discourage Taiwan from taking responsibility for and control of its own defense. They believe they can rely on the U.S., discouraging them from taking ownership of their situation and doing more on their own to either prepare adequate defenses or make political compromises to ease tensions with Beijing.

During 2021–2022, Biden made several troubling statements that strongly hinted that the U.S. was prepared to go to war over Taiwan.73Zack Cooper, “The Fourth Taiwan Strait Slip-up,” American Enterprise Institute, September 19, 2022, https://www.aei.org/foreign-and-defense-policy/the-fourth-taiwan-strait-slip-up/. These statements most certainly contravene America’s traditional policy of strategic ambiguity, and they also violate the One China policy since—unlike with many other U.S. allies—there is no defense treaty between the U.S. and Taiwan. Again, the essence of that policy, developed in the 1970s, involved the recognition of Taiwan as part of China and the abrogation of the defense pact between Washington and Taipei in return for the normalization of U.S.-China bilateral ties. Another round of large-scale PLA exercises around the island followed when Taiwan leader Tsai Ying-wen visited the U.S. during March and April 2023.

Fortunately, a slightly more cautious set of policies seemed to emerge in June 2023 with Secretary of State Antony Blinken stating emphatically during his visit to Beijing, “We do not support Taiwan independence.”74Andrew Mark Miller, “Blinken Says US ‘Does Not Support Taiwan Independence’ during China Visit,” Fox News, June 19, 2023, https://www.foxnews.com/politics/blinken-us-does-not-support-taiwan-independence-china-visit. Likewise, the Biden administration seemed anxious to play down the visit of then-Taiwan vice president Lai Ching-te, with no official meetings or major speeches as he transited through to Latin America.75Amy Chang Chien and Chris Buckley, “As a Taiwanese Presidential Contender Visits U.S., He Tries to Walk a Fine Line,” New York Times, August 12, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/12/world/asia/taiwan-us-china-lai-ching-te.html. Nevertheless, there continued to be signs of potential war preparations, including large-scale military exercises and the deployment of new weapons systems, as well as related diplomatic efforts on both sides.76Jen Judson, “US Army Deploys Mid-Range Missiles for First Time in Philippines,” Defense News, April 16, 2024, https://www.defensenews.com/land/2024/04/16/us-army-deploys-midrange-missile-for-first-time-in-philippines/.

A mid-2023 Council on Foreign Relations report on Taiwan attempts to build a consensus among foreign policy and regional experts around a new approach to the island. Although no consensus was apparently reached on shifting from strategic ambiguity to so-called strategic clarity, the report leans quite heavily in that dangerous direction. It explains, “Some experts… believe… a U.S. shift to strategic clarity can and should be made in a way that is consistent with the United States’ One China policy.”77“U.S. Taiwan Relations…” 54. That conclusion seems to contradict the admission in the same report that Washington “has no intention of… pursuing a policy of ‘two Chinas’ or ‘one China, one Taiwan.’”78“U.S. Taiwan Relations…” 17. Not surprisingly, the same report advocates that the four statements made by Biden that the U.S. would defend Taiwan should become the “new baseline” for American policy toward Taiwan.79“U.S. Taiwan Relations…” 55.

Arguing in a similar vein, Taiwan expert Steven Goldstein suggests that the One China policy is a “misnomer that obscures its full content even as it diminishes its scope and significance.”80Steven Goldstein, “Understanding the One China Policy,” Brookings Institution, August 31, 2023, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/understanding-the-one-china-policy/. He contends that U.S. leaders should instead refer to a “cross-strait policy,” which would encompass all aspects of U.S. policy toward the island and not give the false impression that Washington might “abandon ‘an old friend.’” Ultimately, Goldstein, as well as the CFR report, argue that the One China policy is continually evolving and was “conceived within an environment characterized by Sino-American engagement. Today’s environment is different.”81Goldstein, “Understanding the One China Policy.”

This line of reasoning treats the One China policy as endlessly malleable. It’s an attempt to extirpate “One China” from the One China policy and undo the original compromise made by Nixon and Kissinger. As amply discussed in this paper, that approach is not only dubious from a historical point of view (going back to commitments under the Roosevelt and Truman administrations) but could ruin prospects for U.S.-China relations. By far the biggest consequences of this modification would be the increased risk of superpower war and—barring that catastrophic outcome—the intensification of militarized rivalry that is likely to bankrupt both sides.

That is, U.S. policy, in its eagerness to assure Taiwan and deter China, might actually cause a Chinese invasion. China might see a need to preempt what it views as U.S.-backed moves in Taiwan toward independence. Or it might move to prevent Taiwan from becoming a de facto U.S. ally, exploiting a window of opportunity to settle the Taiwan issue forcibly before the cost of doing so rises even more. Of course, an invasion might come for other reasons—due to the Chinese government’s struggle for legitimacy, especially amid an economic downturn, or a tipping of internal power toward more hawkish elements of the PLA. But those pathways to war are mostly outside U.S. control.

By returning to a traditional understanding of the One China policy, the United States can help preserve peace in the Taiwan Strait. China, in common with both the U.S. and Taiwan, has benefited substantially from the status quo and is not eager to launch a war of reunification that would entail massive risks. Beijing continually insists that it favors “peaceful unification.”82Jiang Chenglong, “China Seeks Peaceful Reunification with Taiwan, But Force Still an Option,” China Daily, June 2, 2023, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202306/02/WS6479743da3107584c3ac38fe.html. Moreover, the period of calm from 2008–16, discussed at length above, demonstrates that cross-strait rapprochement is not out of reach. Even if a military operation to conquer Taiwan proved successful, China would likely suffer a major economic blow from the myriad sanctions that would follow a conflict.

Persons traveling between Taiwan and mainland China (2001-2024)

China-Taiwan tourism and trade flourished after 2008 and Taiwan’s economy benefited from increased people-to-people ties. However, the COVID-19 pandemic reduced tourism to a trickle.

In Ukraine, Beijing’s leaders have once again seen a powerful illustration of the time-worn principle that wars frequently do not go as planned. Whether or not the U.S. and its allies decide to become directly involved in a hypothetical Chinese military operation to subdue the island, the risks would still be very substantial, and Beijing has many times demonstrated significant risk aversion, including with respect to the use of force.83As an example, 13 Chinese sailors were killed in 2011 in Northern Thailand, but Beijing did not consider the use of military force. “13 Chinese Sailors Killed on Mekong River,” Guardian, October 10, 2011, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/oct/10/chinese-sailors-killed-mekong-river. As another example, a hotel in Kabul popular with Chinese nationals was attacked in December 2022, but again there was no consideration of Chinese military action. “Deadly Attack on Kabul Hotel Popular with Chinese Nationals,” Al Jazeera, December 12, 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/12/12/deadly-attack-on-kabul-hotel-popular-with-chinese-nationals. It is worth underlining that China has not resorted to the large-scale use of force since 1979. That is a very hopeful sign and suggests that diplomacy, if given a chance, can substantially resolve, or at least dampen, related tensions. Beijing’s cautious disposition is reason to think that a mix of skillful diplomacy and restraint by Washington can lower the likelihood of a cross-strait war.

Yet it’s worth dwelling on the question of how specifically this war might come about. What would be the precise causal mechanism behind a Chinese decision to use force against Taiwan?

The war could start due to China’s domestic politics, the role of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the role of China’s military, or the health of the Chinese economy. Not long ago, for example, the CCP appears to have encountered a major challenge in the domain of COVID restrictions. Extremely draconian regulations, enforced by party cadres, brought many Chinese cities to the point of major anti-regime protests.84Jennifer Jett and Mithil Aggarwal, “Protests Against Covid Lockdowns Sweep China, Challenging Xi Jinping,” NBC News, November 28, 2022, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/china-protests-lockdowns-xi-jinping-covid-zero-rcna58909. This period of instability seems to have passed quite quickly after the dropping of the pandemic-related restrictions, but it is reasonable to suppose the CCP might significantly harden its Taiwan policies if a crisis of legitimacy were to reemerge in different circumstances.85See Shoon Murray, “The ‘Rally-‘Round-the-Flag’ Phenomenon and the Diversionary Use of Force,” Oxford Research Encyclopedia, June 28, 2017, https://oxfordre.com/politics/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-518. Many observers of China’s cultural scene have suggested that jingoism may be on the rise, particularly among the country’s youth.86Anthony Kuhn, “Chinese Blockbuster ‘Wolf Warrior II’ Mixes Jingoism With Hollywood Heroism,” NPR, August 10, 2017, https://www.npr.org/2017/08/10/542663769/chinese-blockbuster-wolf-warrior-ii-mixes-jingoism-with-hollywood-heroism.

Given the extraordinary stakes and associated costs of great power armed conflict, it makes sense to take with utmost seriousness Beijing’s frequent admonishments that the U.S. is “playing with fire.” The immense costs of a U.S.-China war would involve enormous military and economic losses. Even if war does not result, militarized rivalry will cost the U.S. trillions of dollars that could have been spent improving living standards at home, not to mention the opportunity costs in other domains. The realistic, restraint-oriented response will be to engage with energetic diplomacy, decrease military tensions where possible, and strengthen the One China policy as the best possible defense of the status quo to prolong Taiwan’s autonomy.

In fact, as the danger of a U.S.-China war over Taiwan comes more and more into focus, some reasonable observers, including in Taiwan, appear to recognize that a diplomatic compromise is required to prevent a conflict that would almost certainly bring devastation to the island and perhaps the end of its autonomous status.

Thus a former senior minister in Taiwan recently called for “down-to-earth realism” from her fellow islanders and suggested, “It’s not that the common folk believe resisting China is futile but that Taiwan will always be within China’s immense gravitational pull and that pragmatism, even accommodation with China, might be preferable to war.” She also noted that several dozen Taiwan scholars had recently signed an open letter calling for “Taipei to chart a middle path between China and the United States.”87Yingtai Lung, “In Taiwan, Friends Are Starting to Turn Against Each Other,” New York Times, April 13, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/18/opinion/taiwan-china-war-us.html. Such sentiments illustrate why having Washington pursue “strategic clarity” is myopic and undermines the potential for a negotiated solution to the estrangement.

Annette Lu, a former vice-president of Taiwan, also spoke out publicly in favor of a “commonwealth” or confederation-type solution to the Taiwan issue that would link Taiwan and the mainland in some respects, even as they maintained separate governments—a concept akin to the European Union. While chided as a “fantasy” in the New York Times, this leading American newspaper also admitted that “The notion of a commonwealth or federation of independent Chinese states has been touted as a solution to Taiwan’s dilemma for decades by academics, editorials and minor officials on both sides of the strait.” The article also points out that nearly 10 percent of Taiwan’s population already lives and works on the mainland, suggesting that day-to-day practicalities of closer ties may transcend ideology and illustrate a deeper reality in the cross-strait relationship.88This paragraph is drawn from Farah Stockman, “A Chinese Commonwealth? An Unpopular Idea Resurfaces in Taiwan,” New York Times, March 12, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/12/opinion/international-world/taiwan-china.html.

In the spring of 2023, the former president of Taiwan, Ma Ying-jeou, made a historic first visit to mainland China.89Nicoco Chan, “‘We Are All Chinese’ Former Taiwan President Says While Visiting China,” Reuters, March 28, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/we-are-all-chinese-former-taiwan-president-says-while-visiting-china-2023-03-28/. He was thronged by well-wishers and the mainland news services provided wide coverage of the returned native son. Reflecting on this trip, it seems ever more evident that what Taiwan needs is not militarized political theatrics, but rather diplomatic creativity, conflict management, people-to-people engagement, and pragmatic compromise.

U.S. policy can help preserve Taiwan’s autonomy, but it needs to be much more cautious, nuanced, and creative to do so. A viable peace process would support the fundamental U.S. national interest in avoiding a great power war and bringing peace to the Taiwan Strait. A consistent and close adherence to Washington’s One China policy will lower temperatures and enable such a process of national reconciliation.

Americans need to return common sense to their East Asia policy, especially with respect to Taiwan. A commonsense glance at the map and appreciation of economics yields that there is no longer any “military balance” across the Strait and this has been true for decades. A commonsense read of history, culture, and identity politics suggests that the emergent superpower that is contemporary China will not give up on its dream of unification with an island bearing the constitutional title “Republic of China.” A commonsense appreciation of the history of American foreign policy suggests that the deal was done with Beijing when the U.S. withdrew its military forces from the island (including nuclear weapons) long ago. American leaders need to shift away from putting all their chips in the deterrence basket—an increasingly risky gambit—and reach for restraint and diplomatic alternatives, which really do exist.

Preserving strategic ambiguity and the One China policy

Farsighted diplomacy and reconciliation as described above are needed to avoid war. Fortunately, the possibility of a negotiated solution does exist, as demonstrated by the Xi-Ma meeting in December 2015 and the many agreements that Taipei and Beijing reached in the years prior to that historic summit. Moreover, it is essential to develop a viable diplomatic strategy in the present time, before the onset of a war-threatening crisis. During crises, leaders and whole societies are prone to emotional decision-making and the scope for rational compromise narrows considerably.90See, for example, Institute of Medicine (US) Steering Committee for the Symposium on the Medical Implications of Nuclear War, The Medical Implications of Nuclear War, Solomon F, Marston RQ, ed. (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 1986), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK219168/.

A major pillar of current U.S. policy on Taiwan is “strategic ambiguity” and this must be preserved for the foreseeable future. While the policy has some obvious drawbacks—not least allowing for the churning of crisis circumstances to play into decision-making—such costs are still outweighed by considerable benefits. The policy has been adopted to enable “dual deterrence.” This means Beijing cannot be sure the U.S. will stand aside in a Taiwan conflict. Such a deterrence posture has likely been a factor in maintaining peace across the Taiwan Strait since 1949, a considerable achievement.

At least as important, however, is the other deterrence component of strategic ambiguity, and this is intended to impact Taipei’s calculations. Nationalism and identity politics are well-understood causes of conflict and it is quite clear that identities have been shifting in Taiwan. Younger generations appear to feel much more separated from Chinese identity. Thus there is a significant danger Taiwan’s leaders will increasingly push the envelope with respect to the One China policy, adopting policies that look ever more like full separation and even independence. Even Taiwan supporters seem to accept that Taipei should respect certain limits, suggesting Taiwanese leaders have sometimes overreached, as in the case of Chen Shuibian in 2003, which elicited a public rebuke from the American president as a unilateral attempt to change the status quo.91Goldstein, “Understanding the One China Policy.”

In maintaining strategic ambiguity, moreover, some additional drawbacks of the alternative “strategic clarity” deserve further explanation. These arguments have been cogently made by DEFP fellow Peter Harris in a recent paper. He observes, first of all, that a strengthened U.S. defense commitment to Taiwan is not likely to be credible given the island’s proximity to China, but also because it is a “core interest” for Beijing and not for Washington. As a second reason, Harris notes that credibility cannot be strengthened with the usual tools, such as tripwire forces, due to the fact that any deployment of significant U.S. forces to the island would likely initiate the conflict as a casus belli. A third problem with clarity is that it would likely enhance Taiwan’s dependency and promote “free-riding”—an enduring problem in U.S. defense policy over the last few decades. Finally, a move to strategic clarity would no doubt fully ruin both the China-Taiwan bilateral relationship and the U.S.-China bilateral relationship with massive deleterious consequences across all domains of global governance, not least on the vital issue of climate change.92This whole paragraph is drawn from Peter Harris and Jared M. McKinney, “Strategic Clarity or Calamity: Competing Logics of Deterrence in the Taiwan Strait,” International Affairs 100, no. 3 (2024), 1171–87.

Beyond maintaining strategic ambiguity, it is imperative to re-energize the One China policy. Paul Heer, a China specialist and former U.S. intelligence officer, has wise recommendations on this crucial matter. Heer urges the U.S. to stop thinking of the Taiwan issue in exclusively military terms, a tendency that “evades the central problem.” He explains, moreover, that Beijing is not eager to use force, but it will also not renounce the use of force so “we need to give [China] a reason not to.” That should include a diplomatic process in which the U.S. is directly involved, but also one that offers reassurance to Beijing. Most importantly, Heer emphasizes that Washington must “review our one China policy with an eye toward making it substantive, credible, and persuasive, which it increasingly is not.” He notes that this will also require counseling Taipei to act in accordance with a One China policy. Finally, he observes that “upgrading U.S. interactions with Taiwan” are often “not consistent with the one China policy….”93This whole paragraph is taken from personal communications with Paul Heer, March 2022, used with permission.