October 16, 2025

Target Taiwan: Limits of allied support

This explainer is part of the series "Target Taiwan"

Key Points

- The United States is counting on its allies for assistance in defending Taiwan, but alliances are hardly a cure-all for Taiwan’s defense.

- Australia has fought alongside America in every war for the last century, but there is little reason to think Canberra’s participation in a Taiwan scenario would make a serious difference, even taking into account the much-heralded AUKUS deal of 2021.

- South Korea is a powerful U.S. ally, and India is a growing and important partner, but neither is likely to meaningfully participate in a prospective Taiwan war.

- While certain East Asian countries, such as the Philippines, can offer access to advantageous locations, they will add no genuine military capability. Nor will European forces be involved at any more than a symbolic level.

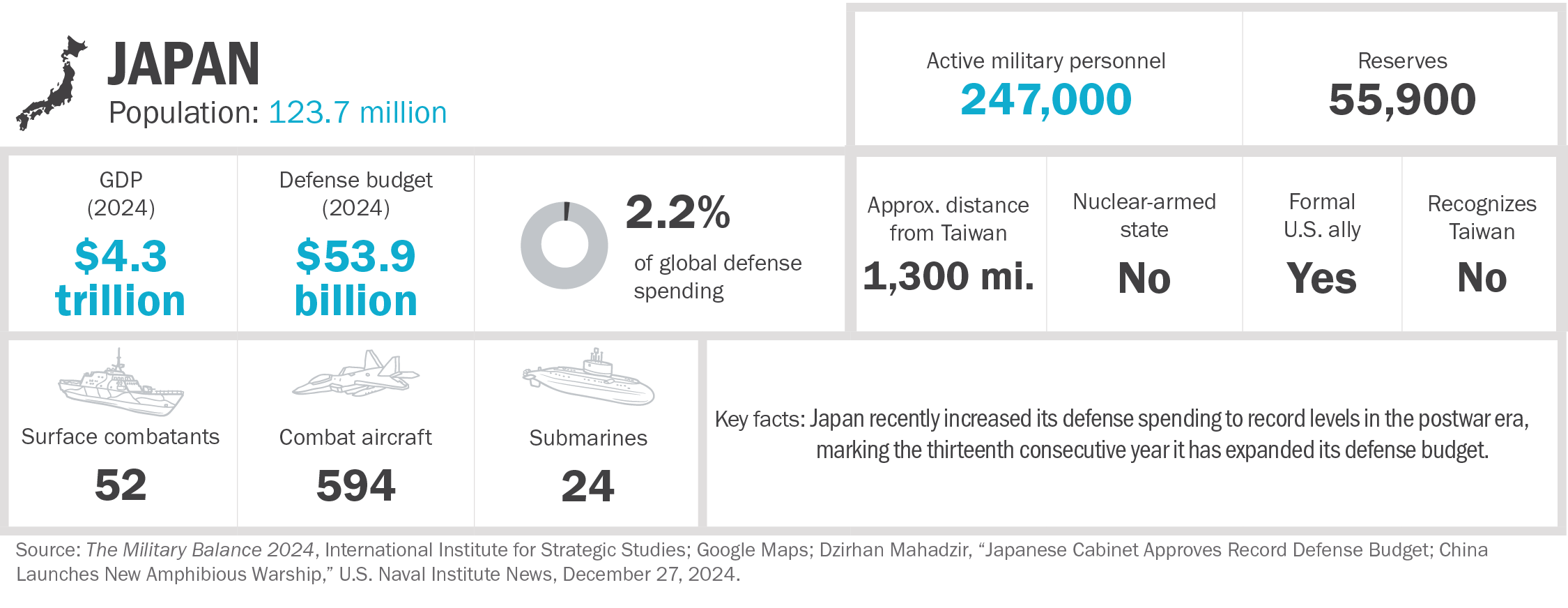

- Japan is far and away the most important of America’s allies with respect to Taiwan, and Tokyo has been pushing hard for Washington to more fully embrace Taiwan’s defense. However, it’s unlikely Tokyo is ready to pull its weight in a war with China over Taiwan. Instead, Japan would likely opt for a middle way, refraining from dispatching military forces while allowing U.S. forces to use its bases.

The United States has a plethora of alliance partners, including in the Asia-Pacific, and many strategists hold that they are key to addressing the Taiwan conundrum. According to the conventional wisdom, while it might be difficult for the U.S. on its own to defend Taiwan indefinitely, allied assistance would make the critical difference. But careful analysis of the allies’ political circumstances and capabilities casts serious doubt on this idea.

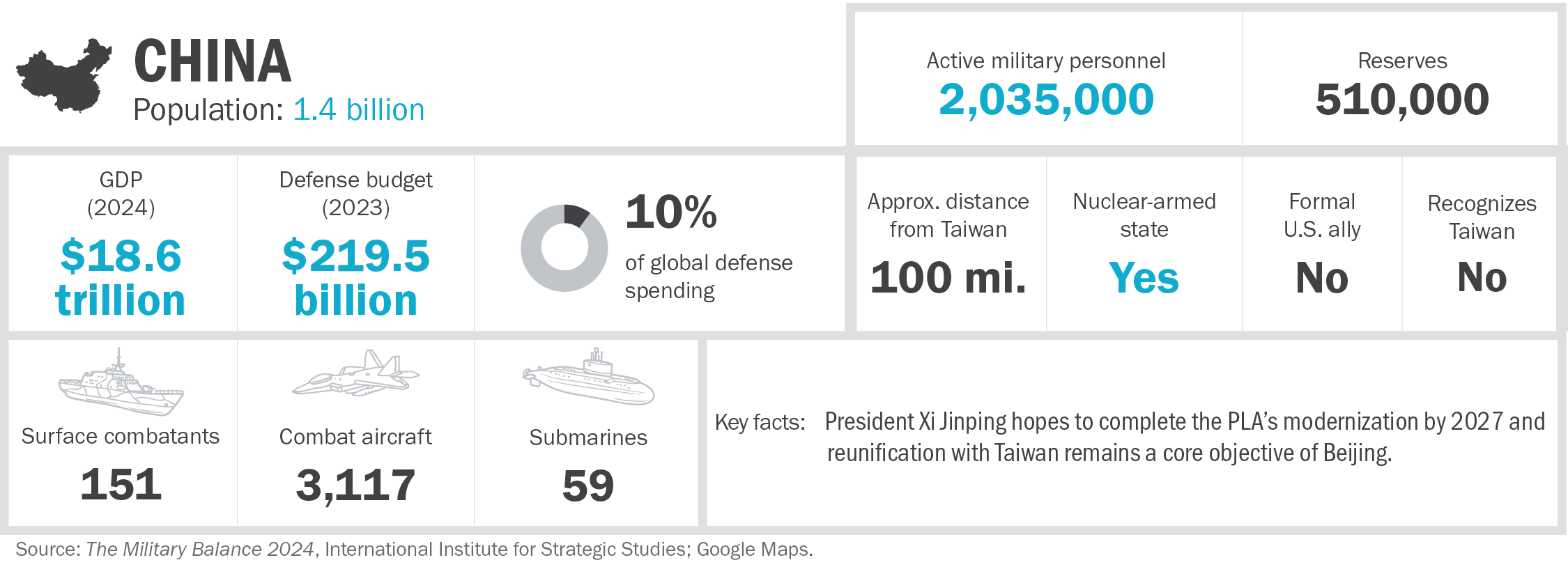

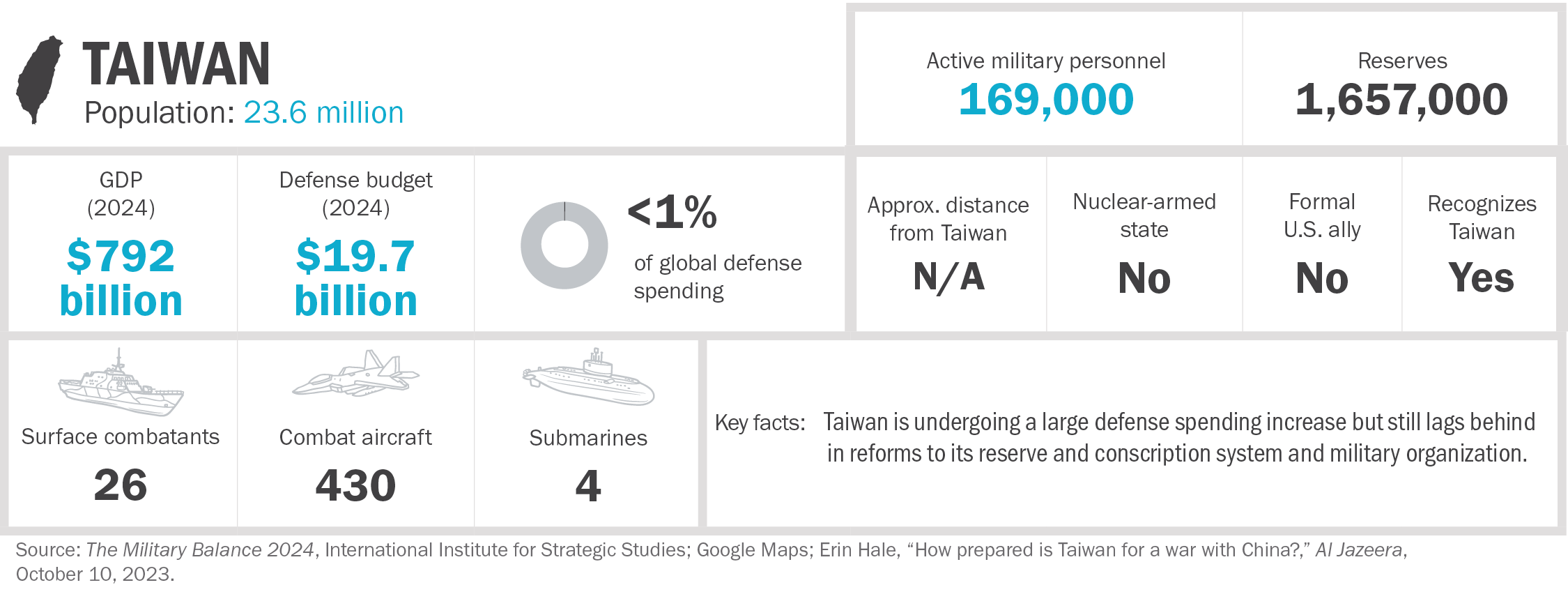

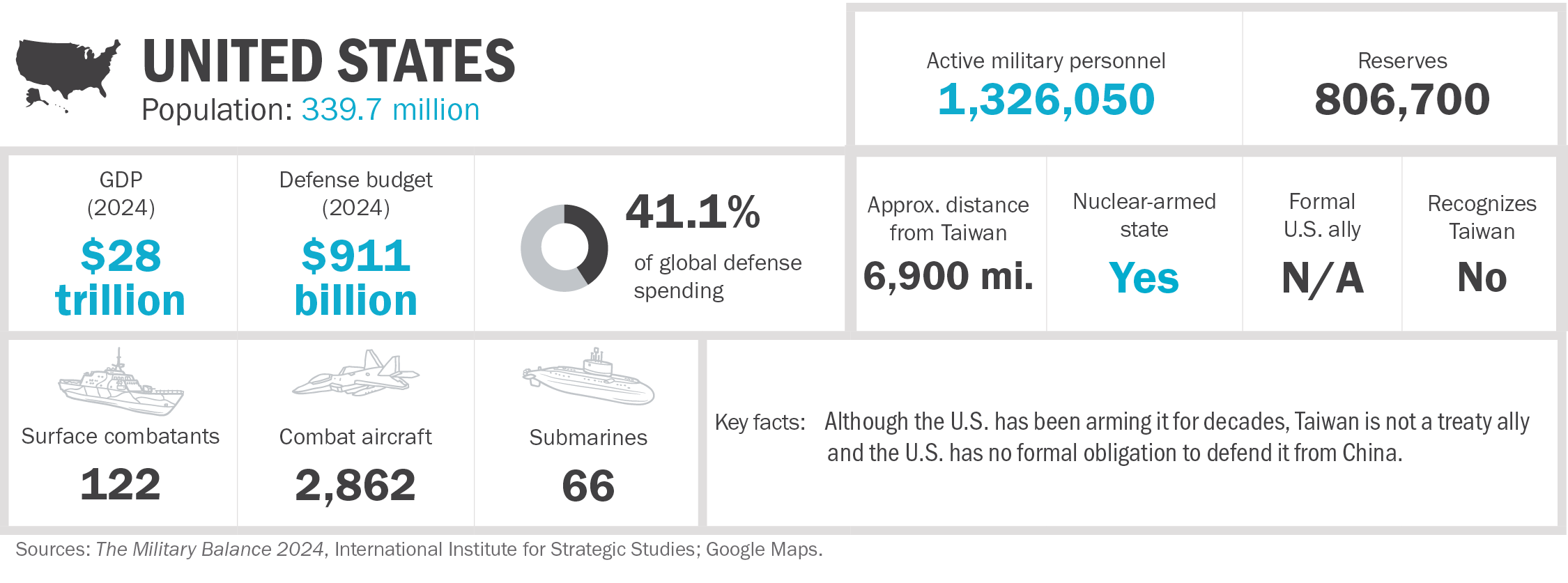

The first explainer in this series evaluated Taiwan’s prospects for holding off a Chinese invasion on its own. The second looked at the United States’ ability to help defend Taiwan. This one considers what U.S. allies might do.

Certainly U.S. allies have considerable capability to aid Taiwan. South Korea has more than half a million troops under arms, and almost a three million-strong reserve force. Japan’s self-defense force is significantly smaller but is known for its high proficiency and professionalism. Australia’s forces are smaller still, but this rather elite military has joined with American forces in almost every recent U.S. war. Beyond these stalwart allies is the allure of India, which has a strong martial tradition and the makings of a possible military superpower. Many sympathetic states, moreover, have further military potential, such as the Philippines and Indonesia. Then there is Europe, which, though distant from Taiwan, has nevertheless demonstrated an increasing ambition to become more involved in the security domain of the Asia-Pacific.1See, for example, Mirna Galic, “Amid Changing Global Order, NATO Looks East,” U.S. Institute for Peace, April 23, 2024, https://www.usip.org/publications/2024/04/amid-changing-global-order-nato-looks-east.

All this amounts to a house of cards when it comes to defending Taiwan. On paper, the amalgam of countries would seem to mitigate the vicious tyranny of distance disadvantaging the United States, along with an increasingly lopsided imbalance of forces favoring China. However, none of these allies has demonstrated both the will and the capability to make a meaningful difference in support of a U.S. military intervention to protect Taiwan from mainland China. Former U.S. intelligence official and Asia expert John Culver has said, “I think you’d get a chilling set of answers if you approached authoritative people in our treaty allies. …Will you assist in preventing Chinese conquest [of Taiwan]? With maybe one or two exceptions, I think the answer we would get is no.”2John Culver quoted in Mark F. Cancian, Matthew Cancian, and Eric Heginbotham, The First Battle of the Next War: Wargaming a Chinese Invasion of Taiwan (Washington DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, January 2023) 60.

Except for Japan and to a lesser extent South Korea, Asia does not see Taiwan as an existential or core national security interest and may even harbor significant sympathy for China’s claims to Taiwan. There’s also the matter of China’s nuclear weapons. While Beijing has a no first use (NFU) policy, and other Asian states have nuclear weapons as well, even the possibility of a nuclear war is likely to make America’s allies think twice about getting involved in a Taiwan scenario.

As demonstrated in the analysis that follows, “partners” currently in fashion—for example, India and Vietnam—are very unlikely to get involved. Logistics challenges would be daunting for any U.S. campaign to secure Taiwan, and many East Asian countries might well “passively” contribute to keeping U.S. forces provisioned. But when it comes to hard power, the situation is bleak: treaty ally Australia has the will but lacks the capacity, while South Korea has the capacity but lacks the will. Only Japan comes closest to meeting both requirements, but Tokyo is also quite unlikely to definitively resolve Washington’s Taiwan dilemma.

This explainer does not consider all aspects of alliance behavior, nor does it try to examine every possible variation of a Taiwan scenario. The focus is on the potential military contributions of allies and partners, rather than political support or economic issues, such as possible sanctions policies. Similarly, it is recognized that allied responses could vary significantly according to the degree of coercion that Beijing opts for, which could range from a symbolic show of force to a limited attack to a blockade to an all-out attack. In order not to over-complicate this analytical effort, this explainer, like the others in this series, is focused on the high-end scenario—namely an all-out Chinese attack on Taiwan. Moreover, this explainer does not speculate on the details of exactly how the fighting might begin, though it is recognized that more aggressive Chinese coercive actions could elicit more stout responses from U.S. allies and partners than if Beijing was reacting to a crisis it had not initiated.

Allies in vogue under Biden, in question under Trump

Allies have had a crucial place in U.S. strategic thinking towards China going back decades. This position was substantially elevated during the Biden administration, partly as a reaction to the perceived neglect of alliances during the first Trump administration.

In his first major foreign policy speech at the State Department in February 2021, Biden emphasized that “America’s alliances are our greatest asset and leading with diplomacy means standing shoulder-to-shoulder with our allies and key partners once again.” He identified China explicitly as “our most serious competitor,” and promised to “compete from a position of strength” and “catalyze global action” by reenergizing U.S. engagement and leadership.3This whole paragraph is drawn from President Joe Biden, “Remarks by President Biden on America’s Place in the World,” White House, February 4, 2021. For current access, see the U.S. Embassy in Estonia, https://ee.usembassy.gov/2021-02-04/.

Biden’s chief foreign policy advisors tried to realize this vision for the Asia-Pacific. U.S. national security adviser Jake Sullivan in November 2021 delivered a speech at a prominent Australian think tank, the Lowy Institute, and asserted that the U.S. seeks “to build a latticework of alliances and partnerships globally that are fit for purpose for the twenty-first century” that “are not just about refurbishing the old bilateral alliances, or refurbishing NATO… but modernizing those elements of the latticework and adding new components as we go.”4Jake Sullivan, “The 2021 Lowy Lecture,” Lowy Institute, November 11, 2021, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/publications/2021-lowy-lecture-jake-sullivan.

One month later, then-Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe suggested that Chinese coercion of Taiwan represented a major threat to Japan. Days later, then-U.S. secretary of defense Lloyd Austin spoke with his Japanese counterpart, Nobuo Kishi, and they reportedly agreed “to deepen defense cooperation to maintain regional deterrence.”5Jeff Seldin, “US Defense Secretary Talks Regional Stability with Japanese Counterpart,” VOA News, December 4, 2021, https://www.voanews.com/a/us-defense-secretary-talks-regional-stability-with-japanese-counterpart/6339578.html.

Speaking in Jakarta at about the same time, then-secretary of state Antony Blinken said the U.S. has “an abiding interest in peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait,” and asserted that “We’ll work with our allies and partners to defend the rules-based order that we’ve built together….”6“Blinken Slams ‘Aggressive’ China; Vows Stronger Indo-Pacific Ties,” Al Jazeera, December 14, 2021, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/12/14/blinken-vows-stronger-defence-economic-alliances-in-indo-pacific.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 understandably distracted top Biden administration officials from the Asia-Pacific region, but it also stoked their determination to rely ever more intensively on alliances, since further expanding and strengthening NATO has been a key Washington response to Russian aggression. Senior Biden administration officials explicitly linked their Ukraine strategy to the Taiwan issue, noting that China was watching “carefully.”7“Blinken warns that China is watching the world’s response to war in Ukraine,” posted March 22, 2023 by Reuters, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RBS98gjf2VY. This implied senior U.S. leaders were considering applying similar formulas if they were to confront a Taiwan scenario. Blinken explained, “I think if China’s looking at this [war in Ukraine]… they will draw lessons for how the world comes together, or doesn’t.”8“Ukraine War Has ‘Profound Impact’ on Asia, Blinken Says, with Eye on China’s Ambitions,” Guardian, March 22, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2023/mar/23/ukraine-war-has-profound-impact-on-asia-blinken-says-with-eye-on-chinas-ambitions.

Not surprisingly, under Biden, alliances and coalitions formed a major theme of the U.S. National Security Strategy. In the cover letter signed by Biden, he emphasized the roles played by both AUKUS and the Quad in the Asia-Pacific region, and asserted that “partnerships amplify our capacity to respond to shared challenges.”9“National Security Strategy,” White House, October 2022, https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/8-November-Combined-PDF-for-Upload.pdf, 2–3. One of the clearest manifestations of the invigorated alliance strategy for defense in the Asia-Pacific was the dynamic process of trilateral defense integration among Seoul, Tokyo, and the U.S. during 2023, under which defense coordination meetings were held at a frenetic pace.

President Trump takes a very different view of the U.S. system of alliances. At a minimum, he seems to believe that alliance partners have taken advantage of American largesse and wants to see redress through burden-sharing. Trump’s complaints against NATO members’ underspending on defense are well known, though in the first Trump administration there were major tensions with both Japan and South Korea as well. A late 2019 report declared that both of these relationships were on the verge of “rupture” because Trump was “trying to shake down Seoul and Tokyo.”10Bruce Klinger, Jung H, Pak, and Su Mi Terry, “Trump Shakedowns are Threatening Two Key US Alliances in Asia,” Brookings Institution, December 18, 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/trump-shakedowns-are-threatening-two-key-u-s-alliances-in-asia/.

On the other hand, there is no question that Secretary of State Marco Rubio believes that U.S. alliances, including in the Asia-Pacific, are “indispensable.”11See, for example, Senator Marco Rubio, “Rubio: U.S. Alliances With NATO, South Korea, Japan As Indispensable As Ever,” April 6, 2016, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yoCa-qCx4IE&t=2s. Despite tensions, it is likely that even under Trump, allies will play a key role in U.S. thinking about a Taiwan scenario.

With respect to Washington’s long-maintained affection for alliances, one may reasonably note that constant talk of alliances and partners may reflect political imperatives rather than military ones. In recent U.S. wars, such as in Iraq and Afghanistan, most allies gave only token forces, though those forces were touted in the U.S. with the goal of shoring up support both at home and abroad by increasing the wars’ legitimacy. These same political imperatives likely apply to East Asia too.

On the other hand, some allied nations have contributed significant fighting forces to U.S. efforts on a regular basis, such as Australia.12On Australia’s involvement in Afghanistan, see, for example, John Blaxland, “Twenty Years in Afghanistan – What Did Australia Achieve There, and What Did We Learn?” Wartime 96, accessed at Military History and Heritage Victoria Inc., October 18, 2021, https://www.mhhv.org.au/twenty-years-in-afghanistan-what-did-australia-achieve-there-and-what-did-we-learn/. In a Taiwan scenario, all possible contributions would likely be considered since the U.S. would be seeking a maximum coalition rather than a minimum one. Yet strategists should not be deceived by the alliance-focused rhetoric that is now so common in U.S. diplomacy but should rather focus narrowly and realistically on how such a scenario might play out if only a minimum of help is available.

Having established Washington’s inclination to rely heavily on alliances in the Asia-Pacific, let us examine both the capabilities and willpower of the various relevant U.S. allies. These allies have been selected on the basis of having some geographic proximity to Taiwan, and thus come from three regions: East Asia, Southeast Asia, and the South Pacific. A possible European role is also addressed. This analysis does not cover countries that support China (i.e. North Korea) or small islands that wouldn’t be able to contribute much to a defense of Taiwan (i.e. Brunei). Such islands—others include the Marshall Islands and East Timor—could become targets for potential airbases if a larger war were to break out, but beyond that they wouldn’t factor much into a Taiwan scenario, especially since many of them are quite distant from Taiwan itself.

The “bookends” of such an exploration are naturally Australia and Japan. Yet there are more than a few vital nuances concerning other allies, which inhabit a nebulous zone of inclining toward Washington’s position while likely being unable to commit significant forces for the foreseeable future.

Australia

Australia is a continent-sized nation and a member of the Quad, the Indo-Pacific-focused security group that also includes the U.S., Japan, and India. A close ally of the United States, Australia has supported the U.S. in nearly every military conflict of the last century. It’s a party to the so-called AUKUS submarine cooperation plan, which unites Australia with the United Kingdom and the United States. Australia’s relations with China have seen some improvement since mid-2022, but this comes after years of turbulence due to acute strains over trade, Chinese influence operations, and, perhaps most important, China’s new reef bases in the South China Sea.

Australia has a powerful military but is reliant on the United States for sealift, which, combined with its sheer distance from Taiwan, could diminish its effectiveness in any Taiwan scenario. Australia is unlikely to provide much help at any rate, given that its left-wing Labor Party is in government and its economic prosperity is dependent in part on access to Chinese markets.

Capacity

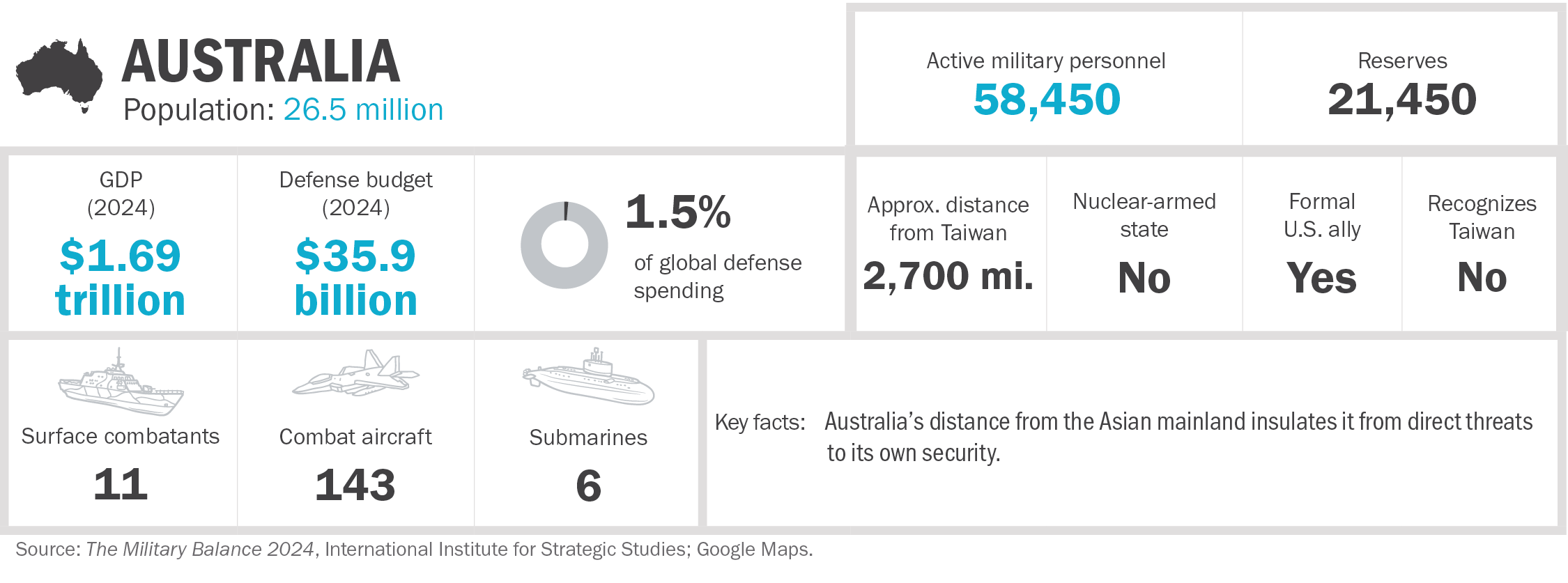

Australia has strong and battle-tested armed forces. The country wields over 100 combat aircraft, 11 surface combatants, and six diesel submarines.13Military Balance 2024, International Institute of Strategic Studies (Oxfordshire: Routledge, 2024) 247–48. Unlike India (see below), the military platforms in Australia are largely imported from the U.S., such as the F-18 Hornet fighter-attack aircraft, simplifying interoperability, logistics, and also maintenance. Canberra also possesses certain niche capabilities that could be especially useful in a Taiwan scenario, such as robust anti-submarine aircraft (both rotary-wing and fixed-wing) as well as special forces (e.g. diver units).14Military Balance 2024, 247.

Since late 2021, the U.S.-Australia relationship has been much in the news due to the announcement of the AUKUS deal. This agreement would allow Australia to access nuclear technology and build its own nuclear submarine force with combat-ready nuclear boats available sometime after 2040.15“AUKUS Nuclear-powered Submarine Pathway, House of Representatives, Parliament House, Canberra ACT,” Defense Ministry of the Australian Government, March 22, 2023, https://www.minister.defence.gov.au/statements/2023-03-22/aukus-nuclear-powered-submarine-pathway-house-representatives-parliament-house-canberra-act. To close this very substantial time-lag, the agreement also envisions a number of interim steps, including Australia’s acquisition of SSN-AUKUS submarines combining British and American technology by 2030, and the purchase of three to five American Virginia-class submarines in the early 2030s. The UK and U.S. will also start to “deploy their own nuclear-powered submarines in the region as part of ‘Submarine Rotational Force-West.’”16Lauren Kahn, “AUKUS Explained: How Will the Trilateral Pact Shape Indo-Pacific Security?” Council on Foreign Relations, June 12, 2023, https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/aukus-explained-how-will-trilateral-pact-shape-indo-pacific-security.

AUKUS’ sharing of naval nuclear propulsion technology began officially in February 2022,17“FACT SHEET: Implementation of the Australia – United Kingdom – United States Partnership (AUKUS),” White House, April 5, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/04/05/fact-sheet-implementation-of-the-australia-united-kingdom-united-states-partnership-aukus/. while the Australian government moved the next month to establish its first nuclear submarine base on the country’s eastern coast, along with a nuclear submarine fabrication facility.18“FACT SHEET: Implementation…” Australian civilian and military personnel began to embed in both the U.S. Navy and the Royal Navy during 2023.19“Joint Leaders Statement on AUKUS,” White House, March 13, 2023, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/03/13/joint-leaders-statement-on-aukus-2/. A new milestone was reached in the training of Australian nuclear submarine-qualified personnel with the announcement in late 2024 of a new training facility in southwestern Australia.20“Growing and Skilling Australia’s Submariner Workforce,” Defense Ministry of the Australian Government, December 9, 2024, https://www.minister.defence.gov.au/media-releases/2024-12-09/growing-skilling-australias-submariner-workforce.

The air component of the U.S.-Australia military alliance is similarly dynamic. In mid-2023, the United States and Australia agreed to partner with Japan in order to undertake joint F-35 strike fighter training in Australia.21“United States-Japan-Australia Trilateral Defense Ministers’ Meeting (TDMM) 2023 Joint Statement,” U.S. Department of Defense, June 3, 2023, https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3415881/united-states-japan-australia-trilateral-defense-ministers-meeting-tdmm-2023-jo/. U.S. nuclear-capable bombers have stepped up deployments to Australia and are likely to be based there semi-permanently.22Miranda Booth, “B-52 Bombers Only Part of a Very Long Australian Story,” Interpreter, Lowy Institute, November 2, 2022, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/b-52-bombers-only-part-very-long-australian-story. Airfield and logistical upgrades are underway “to support high-end warfighting.”23“Joint Statement on Australia-U.S. Ministerial Consultations (AUSMIN) 2021,” U.S. Department of Defense, September 16, 2021, https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/2780670/joint-statement-on-australia-us-ministerial-consultations-ausmin-2021/. Insofar as some U.S. strategists consider heavy bombers—with their large payloads and stand-off capabilities—to be crucial to a Taiwan campaign, Australia’s myriad, large, and high-quality airstrips could hypothetically represent Canberra’s most important contribution to a U.S. war in defense of Taiwan.24On the importance of bombers to a Taiwan scenario, see Cancian, Cancian, and Heginbotham, “The First Battle of the Next War,” 139.

Chinese military planners are watching these developments carefully. For example, a recent detailed article in PLA Daily observed that joint military exercises in July 2023 were unprecedented in scale and covered the entire territory of Australia. The article called them the most important U.S.-Australian logistical exercises since World War II. In addition, the article noted that many European nations, including France and Germany, sent troops to participate, which was said to reflect an intention to continue to promote the “Asia-Pacificization of NATO.”25The article noted various details, for example that “175,000 gallons of fuel and other equipment and materials were transported from pre-arranged ships at sea to predetermined areas on shore, in an attempt to test the capabilities of the US-Australian coalition forces for transoceanic transportation, pier unloading, and…equipment reception.” See Chen Hanghui and Zhang Chengbao [陈航辉, 张成堡], “The US and Australia Do the Sword Dance, But the Blade is Hard to Sharpen” [美澳舞’刀’, 其刃难利], PLA Daily [解放军报], August 3, 2023, http://www.81.cn/szb_223187/szbxq/index.html?paperName=jfjb&paperDate=2023-08-03&paperNumber=11&articleid=911844. The issue of NATO’s role in the Asia-Pacific is taken up in more detail below, but this article may demonstrate Chinese anxiety that Australia will be an important player in increasing Europe’s role in Asia-Pacific security.

One very serious issue overhangs any role for Australia in the Asia-Pacific: lift. Australia has very limited sealift capabilities, which could hamstring its ability to deploy ground forces in the event of a Taiwan scenario. Historically Australia has relied on the United States to provide the lift and logistical support for its forces to get to other places. For example, in the 2023 Indo-Pacific training exercise called Super Garuda Shield, the U.S. provided sealift for Australian armor to reach Indonesia.26Major Jonathon Daniell, “US Army sustainers provide sealift to Australian armor for Super Garuda Shield,” U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, September 19, 2023, https://www.pacom.mil/Media/News/News-Article-View/Article/3531301/us-army-sustainers-provide-sealift-to-australian-armor-for-super-garuda-shield/. This may not prove too dire a constraint in a Taiwan scenario given that it would likely be more of an air/sea battle than a ground forces battle. But it could still prove an impediment given that Australia is more than 3,500 miles from Taiwan, and the war could start quickly, leaving limited time to get forces to the theater.

Willingness

If Australia has capable armed forces, the question remains as to whether it has the will to use them in a Taiwan fight. Senior Australian decision-makers have addressed the Taiwan issue in a direct manner over the last few years, with then-defense minister Peter Dutton suggesting in early 2022 that if China invaded Taiwan it would not stop taking territory and could end up creating a new regional order.27Anthony Galloway, “Dutton Warns of ‘Next Step’ if China Invaded Taiwan,” Sydney Morning Herald, November 26, 2021, https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/dutton-warns-of-next-step-if-china-invaded-taiwan-20211126-p59ckg.html. Around that time, Australia moved to ink a defense agreement with Japan—a first between the two U.S. allies. They jointly agreed to opposition to “any destabilizing or coercive unilateral actions that seek to alter the status quo and increase tensions” in the East China Sea and stressed “the importance of peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait….”28Junnosuke Kobara, “Japan and Australia Strengthen Quasi-Alliance with Eye on China,” Nikkei Asia, January 7, 2022, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/Indo-Pacific/Japan-and-Australia-strengthen-quasi-alliance-with-eye-on-China.

However, Canberra transitioned from Liberal to Labor party rule in May 2022, and the new Australian government has sought to improve ties with China. Australia-based China expert Richard McGregor notes that a major objective of the government under Prime Minister Anthony Albanese is to lower the temperature of relations with Beijing. He cites evidence that they may have provided “guarantees [to Beijing] on limits of Australian interaction with Taiwan.”29Richard McGregor, “Australia’s Caution on Taiwan May Not Last,” Brookings Institution, March 29, 2023, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/australias-caution-on-taiwan-may-not-last/. Yet he asks whether Australia’s caution on the Taiwan issue is sustainable, noting that the AUKUS deal would appear to rest in the hands of the U.S. Congress: “Would they approve such transfers if they thought Australia was backsliding on Taiwan?”30McGregor, “Australia’s Caution on Taiwan May Not Last.”

On the economic side, Beijing will continue to hold leverage over Canberra insofar as China forms a major export market for Australian goods.31Beijing holds more leverage in this relationship since Australia’s main exports to China, consisting of coal, natural gas, and iron ore, are relatively easily replaced on the world market. Moreover, while China is Australia’s number one trading partner, Australia did not figure into China’s top 10 partners in 2023. See Daniel Workman, “China’s Top Trading Partners,” World’s Top Exports, https://www.worldstopexports.com/chinas-top-import-partners/. Australia’s prospering economy over the last few decades is partly attributable to China’s extraordinary growth and need for Australia’s natural resources. Thus it is not surprising that Canberra’s commercial elites are skittish about a direct confrontation with Beijing. Australian politics have long been riven between pro-China and anti-China factions, and there is no reason to believe this dispute has been resolved. Former prime minister Paul Keating vocally criticized Canberra’s increasing inclination to defend Taiwan in late 2021, and assessed the AUKUS deal as follows: “Eight submarines against China when we get the submarines in 20 years’ time—it’ll be like throwing a handful of toothpicks at the mountain.”32Betsy Reed, “Throwing Toothpicks at the Mountain’: Paul Keating Says AUKUS Submarines Plan Will Have No Impact on China,” Guardian, November 10, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/nov/10/throwing-toothpicks-at-the-mountain-paul-keating-says-aukus-submarines-plan-will-have-no-impact-on-china; see also Anthony Galloway, “Paul Keating Says Defending Taiwan is Not in Australia’s Interest,” Sydney Morning Herald, November 10, 2021, https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/paul-keating-says-defending-taiwan-is-not-in-australia-s-interest-20211110-p597qz.html. For other skeptical expert voices in Australia, see Zach Cooper and Sheena Chestnut Greitens, “Asian Allies and Partners in a Taiwan Contingency: What Should the United States Expect?” American Enterprise Institute, 2022, https://www.defendingtaiwan.com/asian-allies-and-partners-in-a-taiwan-contingency-what-should-the-united-states-expect/.

It could also prove difficult for Australians to link their own security to that of Taiwan. Thus, Keating argued, “Taiwan is not a vital Australian interest… We have no alliance with Taipei. There is no piece of paper sitting in Canberra which has an alliance with Taipei.”33Helen Davidson and Daniel Hurst, “Taiwan hits back after Paul Keating says its status ‘not a vital Australian interest,’” Guardian, November 10, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/nov/11/taiwan-hits-back-after-paul-keating-says-its-status-not-a-vital-australian-interest.

Analysis

Australia brings numerous advantages to the United States’ alliance system in Asia, beyond a common culture and heritage of close military cooperation. The country is distant enough from China that it is not immediately vulnerable to the full range of China’s strike systems.34One recent Australian assessment notes that nearly 40,000 Australian defense personnel served in Afghanistan and that Australia will suffer “long-lasting mental and physical scars.” Gareth Rice, “Learning from Our Mistakes: The Afghan Study,” Cove, December 5, 2022, https://cove.army.gov.au/article/learning-our-mistakes-afghan-study. That makes it quite different from other U.S. allies, which are more proximate and hence more vulnerable to China’s arsenal of A2/AD weaponry. Australia also has about a dozen surface combatants, as well as half a dozen diesel submarines that could marginally increase U.S. aggregate naval combat power in a Taiwan scenario.

Yet there are many reasons to believe that Australia does not offer a neat solution to Washington’s Taiwan dilemma. While the aggregate of Australia’s armed forces is decently impressive, it stands to reason that only a portion would be available to deploy in a Taiwan conflict. Since the AUKUS submarines are unlikely to arrive before the mid-2030s, it could be a decade or more before serious Australian submarine power could be brought to bear in a Taiwan scenario.35Betsy Reed, “Mind the Capability Gap: What Happens If Collins Class Submarines Retire before Nuclear Boats Are Ready?” Guardian, February 27, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2023/feb/28/mind-the-capability-gap-what-happens-if-collins-class-submarines-retire-before-nuclear-boats-are-ready. And even then it isn’t guaranteed. Raising more questions about the feasibility of AUKUS, a 2023 appraisal observes that “Australia has struggled to crew its current subs” and moreover “America’s navy is struggling to acquire enough Virginia-class subs for itself as it races to close the gap with China.”36“The Anglophone military alliance in Asia is seriously ambitious,” Economist, March 13, 2023, https://www.economist.com/asia/2023/03/13/the-anglophone-military-alliance-in-asia-is-seriously-ambitious. Tough issues related to the feasibility of AUKUS have not dissipated in 2024. One press report explains: “Fears that long-standing backlogs at U.S. shipyards and a shrinking submarine fleet could undercut willingness for the sales [of nuclear submarines to Australia] boiled over this week when the Biden administration cut its funding request for the Virginia class.”37Lewis Jackson, “Australia Confident about Receiving Nuclear Submarines even though US Funding Request Cut,” Reuters, March 13, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/australia-confident-about-receiving-nuclear-submarines-even-though-us-funding-2024-03-13/.

In addition, it’s worth noting that if Australia becomes a hub for U.S. submarines in the meantime, that means it will become a target for Chinese missile strikes. Nor is Australian geography ideal: Canberra is more distant from Beijing than is London. In a Taiwan scenario, submarines would have to transit the narrow passages through the Indonesian archipelago and could encounter straits blocked by sea mines and other threats. The 2023 CSIS “First Battle” war game showed that even nuclear submarines have limitations in a Taiwan scenario, first and foremost with respect to their small magazine size.38Cancian, Cancian and Heginbotham, “The First Battle of the Next War,” 111. CSIS’s report also said that China would target shore facilities related to submarine operations, including especially those related to torpedo storage and handling.39Cancian, Cancian and Heginbotham, “The First Battle of the Next War,” 136. CSIS notes that Australia would offer basing, access, and overflight, but cautions that Australian military forces would be “unavailable… for operations around Taiwan.”40Cancian, Cancian and Heginbotham, “The First Battle of the Next War,” 61. It seems safe to conclude that America’s alliance with Australia would not be a game-changer in a Taiwan scenario.

India

India is the most populous nation in the world (having taken that honor from China in 2023) and a rising economic power. It’s a member of the Quad and shares a border with China yet its relations with both Washington and Beijing are complicated. Like Australia, India has much to recommend it as an ally of the United States. It evinces a similar disposition to confront China and it possesses nuclear weaponry. Yet it would be unwise to count on any major support from India in a Taiwan contingency, since India lacks major capabilities, faces other threats, and has demonstrated little inclination to challenge China on the specific issue of Taiwan.

Capacity

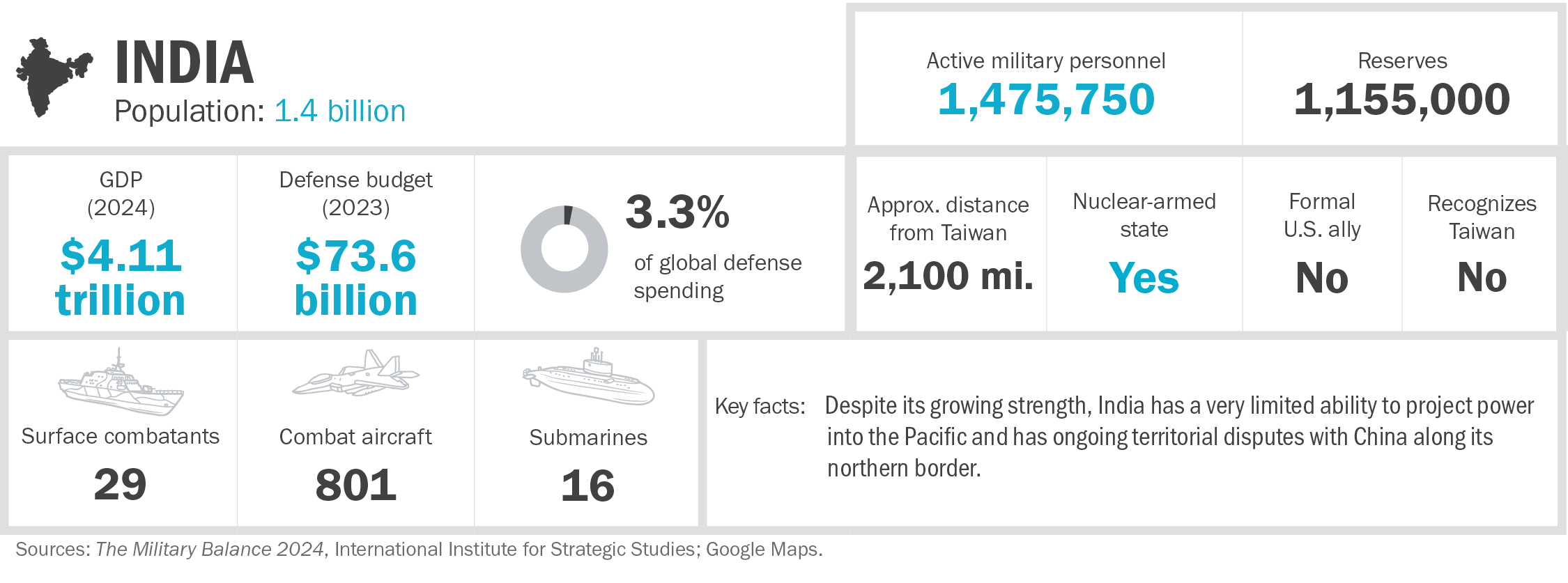

India has an enormous military with almost 1.5 million under arms and more than another million in its reserve forces. With 16 submarines, two aircraft carriers, 11 destroyers, and 16 frigates, New Delhi wields considerable naval capabilities.41Military Balance 2024, 267. India claims the world’s fourth largest air force, possessing nearly 1,000 combat aircraft. Yet such numbers can be deceiving.

Despite its vast size, India’s military is seriously constrained in its ability to project power far beyond the subcontinent. This begins with its defense spending: Prime Minister Modi’s government has embraced a renewed focus on domestic policy after 2024’s tighter-than-expected general election, leaving defense priorities languishing.42Megha Bahree, “India’s Modi urged to set ‘ambitious’ economic agenda after poll humbling,” Al Jazeera, June 9, 2024, https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2024/6/9/indias-modi-urged-to-set-ambitious-economic-agenda-after-poll-humbling. India’s defense spending for FY2025 at $74 billion sits at 1.9 percent of its GDP, the lowest it has been since the 1950s.43Ayush Arya, “India’s defence allocation for FY25 less than 2% of GDP,” Hindu, February 2, 2024, https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/data-stories/data-focus/indias-defence-allocation-for-fy25-less-than-2-of-gdp/article67804849.ece; K. Subrahmanyam, “Indian Defence Expenditure in Global Perspective,” Economic and Political Weekly 8, no. 26 (1973): http://www.jstor.org/stable/4362796, 1155.

Between India’s nearly 900 combat aircraft exist just six aerial refueling tankers, severely limiting the reach of New Delhi’s striking power.44Military Balance 2024, 269. Indian airpower has also long been dogged by force sustainment issues doubtlessly made worse by a shrinking defense budget. In 2021, it was reported that the Indian Air Force could count just 31 of its 42 squadrons as operational.45Alex Gatopoulos, “Project Force: Is India a military superpower or a Paper Tiger?” Al Jazeera, February 11, 2021, https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2021/2/11/india-military-superpower-or-paper-tiger. Tellingly, the Indian Air Force’s primary mission is offensive counterair operations, indicating an institutional assumption that it is meant to operate close to home in short-range strike packages mainly geared toward the Pakistani threat, rather than in any kind of Taiwan scenario.46Gary J. Schmidt, ed., A Hard Look at Hard Power: Assessing the Defense Capabilities of Key US Allies and Security Partners, Second Edition, U.S. Army War College Strategic Studies Institute, October 2020, https://carnegie-production-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/static/files/India_-_Capable_but_Constrained.pdf, 136.

India’s navy is also hamstrung by a lack of logistical reach. India’s lone naval base outside the subcontinent is located off Mauritius in the southern Indian Ocean nowhere near the Strait of Malacca, the gateway for Indian vessels looking to enter the Pacific.47Anjana Pasricha, “India Sets Up New Indian Ocean Naval Base,” Voice of America, March 6, 2024, https://www.voanews.com/a/india-sets-up-new-indian-ocean-naval-base-/7516163.html. By the numbers alone, India’s navy is unprepared to conduct significant operations far beyond the Indian Ocean. Despite the ambitions of some Indian navalists, India only fields 20 amphibious vessels and three fleet replenishment oilers. It does not operate a single hospital ship.48Military Balance 2024, 268; for Indian navalist perspectives on amphibious power projections, see Rear Admiral (ret.) Dr. Rakesh Chopra, “Strategic Capabilities for Power Projection: Indian Context,” United Service Institution of India, https://www.usiofindia.org/publication-journal/strategic-capabilities-for-power-projection-indian-context-2.html. India has only ever launched one military operation outside the subcontinent proper—a peacekeeping operation in Sri Lanka in 1987—further suggesting that its military’s institutional knowledge of operating far from home is extremely limited.49Xerxes Adrianwalla, “IPKF in Sri Lanka, 35 years later,” Gateway House, March 2, 2022, https://www.gatewayhouse.in/ipkf-in-sri-lanka-35-years-later/.

As with its air force, India’s navy is also overly dependent on foreign purchases of weapons and other military hardware.50Gatopolous, “Project Force.” Taking the Indian submarine force as but one example, it operates French, German, and Russian designs.51Military Balance 2024, 267. This may partly explain the record of deadly accidents that continues to plague India’s armed forces.52See, for example, “India Defence Chief Killed along with 12 Others in Military Helicopter Crash,” France 24, August 12, 2021, https://www.france24.com/en/asia-pacific/20211208-india-defence-chief-killed-along-with-12-others-in-military-helicopter-crash; Abhijit Singh, “Anatomy of an Accident: Why INS Betwa Tipped Over,” Diplomat, December 9, 2016, https://thediplomat.com/2016/12/anatomy-of-an-accident-why-ins-betwa-tipped-over/.

Willingness

One analysis recently noted of the prospect for a “Milk Tea Alliance” that would unite India and Taiwan, “As the border issue resurfaces, India is seeking opportunities to balance and challenge China, and so the ‘Taiwan card’ is once again emerging as a strategic bargaining chip.”53Jassie Hsi Cheng, “The Taiwan–India ‘Milk Tea Alliance,’” Diplomat, October 20, 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2020/10/the-taiwan-india-milk-tea-alliance. While the content of this discussion is generally political, diplomatic, and economic, it is relevant that Indian warships have been visiting the western Pacific since at least 2007 during the annual Malabar exercises.

On the other hand, India in August 2022 reaffirmed its commitment to a One China policy and to the “exercise of restraint.”54“India sticks to ‘one-China’ policy stance but seeks restraint on Taiwan,” Reuters, August 12, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/india-calls-de-escalation-taiwan-china-tensions-2022-08-12/. Like all Indian prime ministers before him, Narendra Modi has pursued a largely independent foreign policy. In 2023, Modi did respond to U.S. inquiries by commissioning a study examining possible Indian responses to a Taiwan invasion, including “a more extreme scenario… for India to get directly involved along their northern border, opening a new theater of war for China.”55Sudhi Ranjan Sen, “India’s Military Studying Options for Any China-Taiwan War,” Bloomberg, September 8, 2023, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-09-08/india-s-military-studying-options-for-any-china-war-on-taiwan?embedded-checkout=true. But this was not a statement of intent so much as an exploration of options. Analysts generally doubt India has the motivation to get involved in a Taiwan conflict.56Arzan Tarapore, “India has its own reasons for preventing a Taiwan war,” Strategist, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, March 28, 2024, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/india-has-its-own-reasons-for-preventing-a-taiwan-war/.

Recently, there has been quite a bit of excitement in American naval circles about the possibilities for repair and maintenance of U.S. warships in Indian ports.57See, for example, “Third Indian Shipyard Wins U.S. Navy Approval for Ship Repairs,” Maritime Executive, April 9, 2023, https://maritime-executive.com/article/third-indian-shipyard-wins-u-s-navy-approval-for-ship-repairs#:~:text=On%20April%206%2C%20the%20state,effective%20from%20April%205%2C%202024. But it seems prudent to ask if such yards could transition successfully to the complex wartime repairs needed by battle-damaged combatants.

Analysis

Even though China-India relations have been strained since a series of clashes on the two countries’ mountainous border starting in May 2020, New Delhi has nevertheless been relatively cautious, including in partnering with the United States. Strategist Ashley Tellis argues that the U.S. should not have illusions about India’s willingness to assist in a military crisis with China: “Washington’s current expectations of India are misplaced. India’s significant weaknesses compared with China, and its inescapable proximity to it, guarantee that New Delhi will never involve itself in any U.S. confrontation with Beijing that does not directly threaten its own security.”58Ashley Tellis, “America’s Bad Bet on India,” Foreign Affairs, May 1, 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/india/americas-bad-bet-india-modi.

One may speculate that if India is capable of intensifying its challenge to China across its land border, namely in and around Tibet, this may well cause Beijing to be more cautious with respect to Taiwan. However, this hypothesis has so far not been borne out, since China now appears to be simultaneously investing heavily in naval and aerospace power, while steadily upgrading its mountain warfare capabilities and infrastructure. It is quite plausible that, if New Delhi were to intervene in a Taiwan scenario, China could threaten action on the Himalayan border, where most analyses give China the military edge.59See, for example, Mujib Mashal and Hari Kumar, “For India’s Military, a Juggling Act on Two Hostile Fronts,” New York Times, September 24, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/24/world/asia/india-military-china-pakistan.html. Moreover, even Elbridge Colby, a major proponent of an anti-China coalition, concedes, “India… has very little ability to project substantial power into East Asia and the Western Pacific…”

Many in Washington place great faith in the future potential of the Quad, but New Delhi’s distance from Taipei—the two cities are more than 2,700 miles apart—as well as its focus on Pakistan and its solid ties to Russia all suggest that India will be a non-factor in any hypothetical Taiwan scenario.60See, for example, Sadanand Dhume, “Russia’s Influence on India Wanes Even as Affection Lingers,” Wall Street Journal, July 20, 2023, https://www.wsj.com/articles/russias-influence-on-india-wanes-even-as-affection-lingers-china-weapons-trade-putin-b4af1bc8. Quite shockingly, a survey of Indians reported in this article finds that 57 percent view President Vladimir Putin as “favorable” or even “highly favorable.” Even if India were to become far more willing to defend Taiwan, it would lack the ability to project power there for the foreseeable future.

South Korea

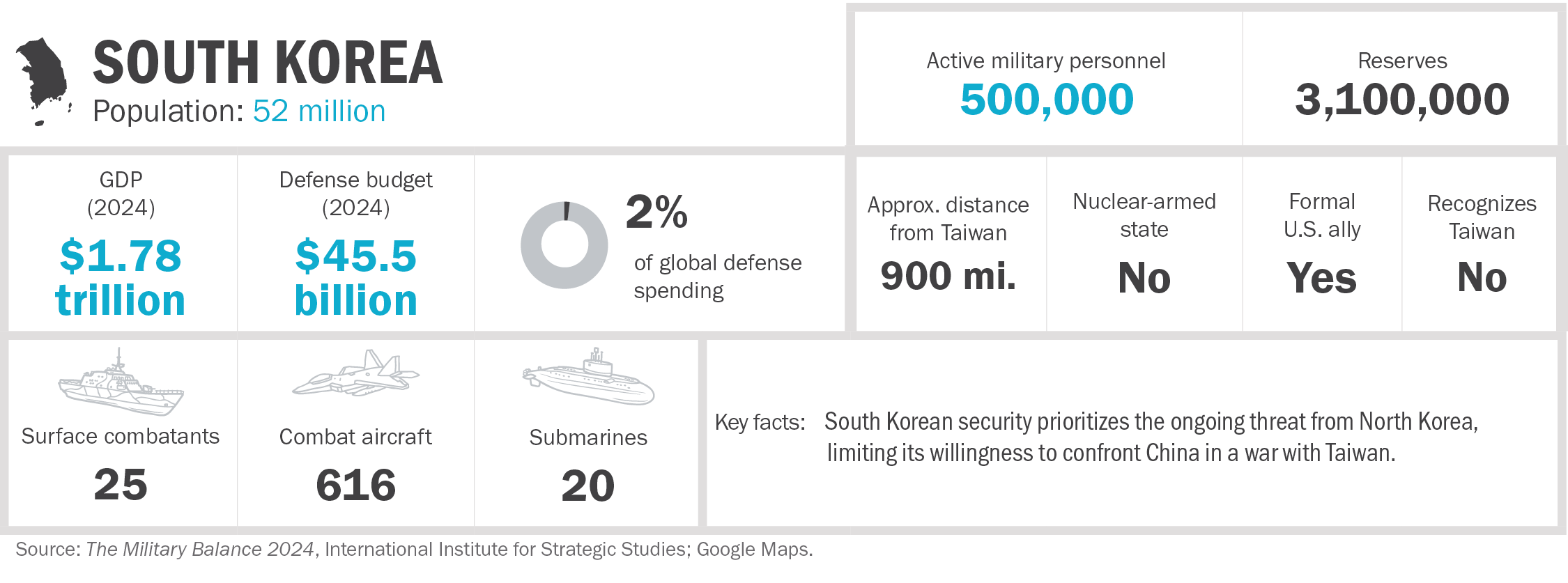

The Republic of Korea occupies the southern half of the Korean Peninsula in East Asia. Its capital Seoul is less than 1,000 miles from Taipei, which is significantly closer than the American military hub of Guam. South Korea is a longstanding ally of the United States, and a partnership between the two nations to stymie Chinese aggression against Taiwan would bring major advantages. South Korea’s armed forces, like India’s, are large, and unlike India’s they would be much more proximate to a Taiwan fight. Nevertheless, there are strong reasons to think that South Korea will abjure from any major participation in a Taiwan scenario, due to the straightforward reasons that it prioritizes the North Korean threat and that Seoul has strong economic ties to Beijing. Such tendencies, moreover, are only likely to be reinforced by the political turbulence that convulsed Seoul in December 2024.61Author’s interviews, Seoul, January 8, 2025.

Capacity

South Korea counts 3,600,000 personnel in its armed forces, with over half a million in the active force—more than double that of Japan, which has a larger economy and population. South Korea’s forces are not just large but maintain a high degree of professionalism, as well as relevant capabilities, including submarines, destroyers, and even ballistic missile forces. Seoul has incrementally increased its defense expenditures and has demonstrated that it will not be easily bullied by Beijing, for example on the issue of missile defense deployments.62Paula Hancocks and Joshua Berlinger, “Missile Defense System that China Opposes Arrives in South Korea,” CNN, March 7, 2017, https://www.cnn.com/2017/03/06/asia/thaad-arrival-south-korea/index.html. South Korea may even possess unique ISR capabilities for monitoring the Chinese armed forces, in part due to its proximity.

South Korea has strong ground forces, as well as substantial air and naval might that could be particularly relevant to a Taiwan scenario. In November 2024, South Korea is expected to receive its first KDX III, reputed to be the world’s most heavily armed destroyer, and this will be the first of six vessels of this class.63YoungHak Lee, “South Korea’s First KDX III Batch II Aegis Destroyer Started Sea Trials,” NavalNews, October 16, 2023, https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2023/10/south-koreas-first-kdx-iii-batch-ii-aegis-destroyer-started-sea-trials/. The South Korean Navy also opened a giant new base off the southern coast of South Korea on the island of Jeju back in 2016, which gets their forces closer to Taiwan than the mainland.64Euan Graham, “A Glimpse into South Korea’s New Naval Base on Jeju Island,” National Interest, June 1, 2016, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/glimpse-south-koreas-new-naval-base-jeju-island-16415. That facility has been described as a “strategic base capable of serving as a blue-water springboard” that can dock and maintain a flotilla of 30 warships.65Graham, “A Glimpse into South Korea’s…” In July 2023, the USS Annapolis docked at the Jeju base to take on supplies.66David Choi, “Another US Submarine Visits South Korea in wake of North Korean Launches, Threats,” Stars and Stripes, July 24, 2023, https://www.stripes.com/branches/navy/2023-07-24/navy-submarine-annapolis-south-korea-10836215.html.

Willingness

While Australia, as noted above, has a new government that is more cautious in dealing with China, the opposite had been true for South Korea. In May 2022, a conservative government led by Yoon Suk Yeol assumed the reins of power in Seoul, taking over from a much more progressive leadership under Moon Jae-in. Although South Korea has steadily increased its defense expenditures over the last decade, which are consistently over 2 percent of its GDP, President Yoon asked for a 4.6 percent increase in 2023.67John Grevatt and Andrew MacDonald, “South Korea Proposes 4.6% Increase in 2023 Defence Budget” Janes, September 2, 2022, https://www.janes.com/defence-news/news-detail/south-korea-proposes-46-increase-in-2023-defence-budget. South Korea’s impressive achievements in defense preparedness and armaments production have made it a major supplier for Europe’s process of rearmament in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.68Ellie Cook, “South Korea is Cashing in on NATO’s Standoff With Russia,” Newsweek, July 17, 2023, https://www.newsweek.com/south-korea-defense-exports-poland-nato-ukraine-war-russia-1813309.

A visit by a nuclear-armed U.S. submarine, an SSBN, to South Korea in mid-2023 marked an upgraded deterrent effort as part of the Washington Declaration that accompanied President Yoon’s state visit to the United States in April 2023. Not surprisingly, Beijing has expressed concern about the increasing U.S.-South Korean collaboration in the domain of nuclear strategy.69See, for example, Lyle Goldstein, “Chinese analysts discuss upcoming US deployment of an Ohio-class ‘boomer’ SSBN on a visit to South Korea,” Twitter, May 8, 2023, https://twitter.com/lylegoldstein/status/1655991208353595429?s=20.

Yoon’s declaration of martial law on December 3, 2024 failed to gain widespread support, as the legislature proved stalwart in defense of South Korea’s democratic institutions. These dramatic events led to Yoon’s downfall and placed his defense and foreign policy initiatives very much in doubt. The successor government to Yoon, under current South Korean president Lee Jae Myung, has been less supportive of higher defense expenditures and sought a rapprochement with Beijing.

These tumultuous developments in Seoul underline other obvious limitations to any South Korean participation in a Taiwan war. First and foremost, the country’s military remains focused on the threat from North Korea, a nation with well over a million in uniform, and so will be highly reluctant to shift forces far to the south. Second, South Korea has a reasonably good relationship with China, and recognizes the value of that relationship for stabilizing the delicate North-South issue. Seoul has opted to distance itself to some extent from U.S. policies with respect to China.

Undoubtedly, Beijing was perturbed by the tightening relationship between Washington and Seoul over the last few years, noting that Taiwan appeared on the agenda of the bilateral relationship for the first time.70See, for example, Lu Chunyan [吕春燕], “Biden’s Efforts to Strengthen the US-South Korean Alliance and Its Impact on China-South Korean Relations” [拜登强化美韩同盟及对中韩关系影响], Peace and Development [和平与发展] 2 (2023): 60–78. China’s leaders have been substantially relieved to see Yoon’s downfall and the consequent rise, once again, of South Korea’s progressives. Of course, the economic factor also looms very large, with China as South Korea’s top trading partner and $268 billion in trade turnover between them during 2023.71Scott Snyder and See-Yon Byun, “S Korean Trade, Diplomacy Trending away from China,” Asia Times, March 28, 2024, https://asiatimes.com/2024/03/s-korean-trade-diplomacy-trending-away-from-china/. While it’s true that Seoul’s exports to China have fallen recently, due largely to new technology restrictions, there is little doubt that South Korea’s economy remains somewhat dependent on good relations with China.

Analysis

Given South Korea’s proximity to China, and hence its vulnerability to coercion, especially in wartime, it is not surprising that Seoul is anxious to avoid being dragged into a U.S.-China war by its alliance with the United States. One could imagine, given how tight U.S.-South Korean cooperation is, that South Korea might offer enhanced ISR to support U.S. forces. Sensors in South Korea are capable of looking deeply into China and thus provide a valuable intelligence resource.72“US Granted Approval to Deploy THAAD in South Korea, Provoking ‘Concern, Displeasure’ from China,” Defense Security Asia, November 24, 2023, https://defencesecurityasia.com/en/thaad-us-china-provoking/. Likewise, South Korean naval and air forces regularly operate in close proximity to Chinese forces, for example around the Yellow Sea area.

Yet Seoul is so sensitive on this issue that it is quite conceivable that U.S. forces would not be permitted to operate out of South Korean bases in a Taiwan scenario. Indeed, the 2023 CSIS “First Battle” war game assumes no active South Korean participation in a Taiwan scenario. If this proves the case, the question is not whether Washington can actively use its bases in South Korea for the war effort, but whether U.S. forces in Korea can or cannot be withdrawn to join the war over Taiwan.73Cancian, Cancian, and Heginbotham, “The First Battle of the Next War,” 60–61. South Korea seems likely to contribute little to nothing if Taiwan is invaded and this inclination has only been strengthened by the recent political events in the South Korean capital.

Philippines

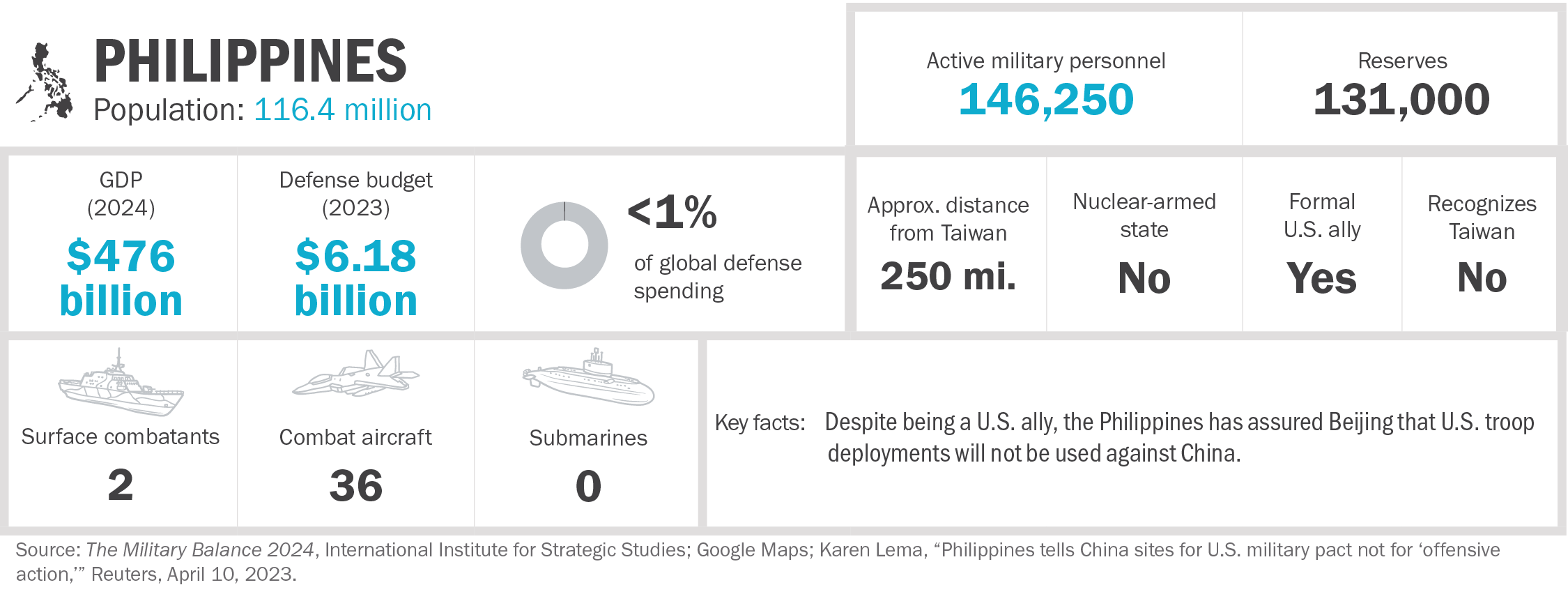

The Philippines is in a much different situation than the countries surveyed above. The archipelago of islands in Southeast Asia would have enormous importance to U.S. forces in any Taiwan scenario due to its proximity. The northern island of Luzon is about 250 miles from Taiwan, but some smaller Philippines islands are just 100 miles to the south. An ever-intensifying dispute between Manila and Beijing regarding maritime claims in the South China Sea, currently focused on Second Thomas Shoal but involving many other locations too, has caused the Philippines government to seek closer security ties with the United States. This builds upon the close cultural ties between the two countries, as the islands were once an American colony, and U.S. forces were key to liberating the Philippines from Japan during World War II.

Still, the Philippines’ proximity to China and weak armed forces make it unlikely Manila will play a meaningful role in a Taiwan scenario. The country’s president has assured Beijing that any U.S. deployments in his country will not be used against China. And the Philippines is simply too vulnerable to China, militarily and economically, to want to risk joining a conflict over Taiwan.

Capacity

One of the Philippines’ biggest assets in a Taiwan scenario would be its geography, which is quite conducive to supporting U.S. military operations. The Philippines would offer significant strategic depth, allowing the Pentagon to build up more forces closer to the fight. That would substantially increase the number of American aircraft sorties, raise the possibility of injecting ground troops into the fight, and enable the rearming and refueling of warships. A dramatic development in 2024 was the U.S. deployment of mobile medium-range Typhon missiles to the Philippines for the first time.74“Philippines Defends U.S. Missile System Deployment, Seeks to Acquire Its Own,” Reuters, December 24, 2024,

https://www.reuters.com/world/philippines-defends-us-missile-system-deployment-seeks-acquire-its-own-2024-12-24/. Chinese strategists registered disquiet about a new system that could range not only the Taiwan Strait but most of the Chinese mainland as well.75“The ‘Typhon’ Threat: The United States Accelerates the Deployment of Medium-range Missile Systems around China” [‘提丰’的威胁: 美国加速在中国周边部署中导系统], Weapon [兵器] No. 304 (September 2024) 40. Moreover, the Philippines’ many disparate islands could enable the creation of “turtle defenses” featuring advanced irregular ground forces and defending “complex” terrain.76Andrew F. Krepinevich, Jr., Archipelagic Defense 2.0 (Washington DC: Hudson Institute, 2023) 143. This report bases this notion on the historical case of the Japanese defense of Iwo Jima in the Pacific War. The idea may gain some support from observing the success of infantry in developing “resilient defense” for extended periods on the Ukraine battlefield, despite lacking air superiority and other firepower advantages. See, for example, Michael Anderson, “How Ukraine’s Roving Teams of Light Infantry Helped Win the Battle of Sumy: Lessons for the US Army,” West Point Modern War Institute, August 17, 2022, https://mwi.westpoint.edu/how-ukraines-roving-teams-of-light-infantry-helped-win-the-battle-of-sumy-lessons-for-the-us-army/. It’s worth pointing out, however, that the Philippines Constitution formally bans the creation of foreign bases on Philippines’ territory.

Even amid an upswing in U.S.-Philippines relations, as well as amenable geography and cultural compatibilities, there should be no illusions about Manila generating usable combat power for a Taiwan scenario. The Philippines has joined U.S. war efforts in East Asia twice before, in Korea and Vietnam, but always in a limited capacity and with vast U.S. support. At the height of its involvement in Vietnam, the Philippines had only 2,000 troops in the country.77Matthew Jagel, “Showing Its Flag: The United States, The

Philippines, and the Vietnam War,” Past Tense: Graduate Review of History 1.2, July 11, 2013, https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/91307/1/showing%20its%20flag_19836-Article%20Text-46661-1-10-20130711.pdf, 32. A conflict with China would require a much more robust effort, yet the Filipino armed forces are ill-equipped to project power without sizable American assistance.

The Philippines’ military is underfunded and almost completely lacking in sophisticated weaponry. It’s hardly considered capable of protecting the Philippines, let alone contributing to the defense of Taiwan. The bulk of the Filipino navy consists of patrol boats and its sealift capability is limited to just 21 amphibious vessels of various kinds.78Military Balance 2024, 307. Its airlift capacity is even more dire. While the Filipino military operates some 36 fixed-wing transport aircraft, the overwhelming majority are foreign-procured light transports like the Airbus C-295M with a carrying capacity of perhaps two infantry platoons. The air force operates just three larger Lockheed C-130s.79Military Balance 2024, 307–308. For an example of the Philippines’ light airlift capabilities in the C-295M, se Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft 2004–05, Paul Jackson ed., 95th edition, (London: Jane’s Publishing Group, 2004) 477–478. The Philippines thus has a glaringly limited ability to ferry forces and equipment through a contested theater to a war zone whether by sea or air.

With just one squadron of 12 Korean-made light combat aircraft, the Filipino Air Force could make little contribution to an air campaign around Taiwan.80Military Balance 2024, 308. The same is true for the Philippines’ paltry naval forces that consist now of just two South Korean-made frigates along with a handful of aging U.S.-made Hamilton-class cutters.81Military Balance 2024, 307. Although Manila has ambitious plans to orient its military away from internal security roles and toward external threats, these plans are very far from realization and may be detached from budgetary realities.82Military Balance 2024, 306.

Willingness

Manila has tended to bounce between extremes in its navigation of the evolving U.S.-China rivalry. A decade ago, the Philippines brazenly challenged China in the Court of Arbitration at the Hague on sovereignty issues in the South China Sea.83See, for example, Pratik Jahar, “Whatever Happened to the South China Sea Ruling?” Interpreter, Lowy Institute, July 12, 2021, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/whatever-happened-south-china-sea-ruling. But soon thereafter, their maverick president Rodrigo Duterte told the U.S. president to “go to hell” and threatened to end all military cooperation with Washington.84Holly Yan, “Philippines’ President Says He’ll ‘Break up’ with US, Tells Obama ‘Go to Hell,’” CNN, October 4, 2016, https://www.cnn.com/2016/10/04/asia/philippines-duterte-us-breakup/index.html. Now, the relationship appears to have come full circle with current President Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. tilting heavily toward the United States and allowing increased U.S. military access at four critical sites in the Philippines. According to one report, “The locations are significant, with [islands] Isabela and Cagayan facing north towards Taiwan….”85Karen Lema, “Philippines Reveals Locations of 4 New Strategic Sites for U.S. Military Pact,” Reuters, April 3, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/philippines-reveals-locations-4-new-strategic-sites-us-military-pact-2023-04-03/. During spring 2023, moreover, the U.S. and the Philippines launched their largest ever joint war games.86Camille Elemia and Alex Willemyns, “Philippines, US Launch Largest Ever Joint War Games,” Radio Free Asia, April 11, 2023, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/southchinasea/philippine-us-war-games-04112023050209.html.

China-Philippines relations were in almost constant crisis during 2024 with ships maneuvering in dangerous ways, including especially at the Second Thomas Shoal, but also near Scarborough Shoal and Sabina Shoal. Chinese bullying in these circumstances sparked the anger of Filipinos, who are seeking to defend their fishing rights in contested waters, along with possible future drilling for hydrocarbons.87Author’s interviews, Manila, January 5–6, 2025.

Nevertheless the Philippines is understandably keen to avoid a war over Taiwan, with its northernmost islands only 118 miles from Taiwan and more than 150,000 Filipinos working on the island.88Mara Cepeda, “Manila says 158,000 Filipinos working in Taiwan are safe amid backlash over Chinese envoy’s remarks,” Straits Times, November 22, 2024, https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/manila-says-158000-filipinos-working-in-taiwan-are-safe-amid-backlash-over-chinese-envoy-s-remarks. Despite its pivot toward the United States, the Philippines still hews closely to a letter-of-the-law reading of its One China policy.89Renato Cruz de Castro, “The Philippines’ evolving view on Taiwan: from passivity to active involvement,” Brookings Institution, March 9, 2023, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-philippines-evolving-view-on-taiwan-from-passivity-to-active-involvement/. Additionally a survey from May 2024 found that 86 percent of Filipinos wanted their country to remain neutral in the event of a Taiwan conflict.90Raissa Robles, “Most Filipinos say they support neutrality over Taiwan, want Manila to focus on home front,” South China Morning Post, May 29, 2024, https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/politics/article/3264470/most-filipinos-say-they-support-neutrality-over-taiwan-want-manila-focus-home-front.

Analysis

The Philippines is likely to stay neutral if China invades Taiwan.91Cancian, Cancian, and Heginbotham, “The First Battle of the Next War,” 61. President Marcos has assured Beijing that U.S. military deployments into his country would not be used against China.92Iain Marlow, “US Can’t Use Philippine Bases for China Offensive, Marcos Says,” Bloomberg, May 4, 2023, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-05-04/us-can-t-use-philippines-bases-for-china-offensive-marcos-says#xj4y7vzkg. Not surprisingly, Chinese strategists are extremely concerned with an enlarged U.S. military presence in the Philippines. Interviews with author in China, March–April 2023. See also a special issue of Naval & Merchant Ships [舰船知识], July 2023, 72–99 that contains five in-depth articles on the continuing evolution of the U.S.-Philippines alliance.

It remains uncertain whether the U.S. would gain access to Filipino military facilities in a Taiwan contingency, especially for use in operations in and around Taiwan (as opposed to in defense of the Philippines itself). ISR and logistics support could represent less risky approaches for the Philippines to back the U.S. in such dangerous circumstances. The Philippines might offer some support to the U.S. by allowing various sensors to be based in their territory. These sensors could be important to helping U.S. forces gain a complete picture of China’s attack in a Taiwan scenario. Likewise Manila might allow some limited help on logistics. A hint of how such support could play out in a Taiwan emergency came in 2024 when rumors suggested that large amounts of aviation fuel had been transferred by the U.S. from Hawaii to the Philippines. Yet that same mini-controversy also showed some of the major political and strategic obstacles to such cooperation in military logistics.93Duncan DeAeth, “U.S. Confirms Fuel Transfer from Hawaii Naval Base to the Philippines: Philippines Senator Suggests Fuel Delivery in Preparation for Possible Conflict over Taiwan,” Taiwan News, January 12, 2024, https://www.taiwannews.com.tw/news/5076880. The article reveals internal political discord in the Philippines and suggests that the oil supplies were to be held in commercial storage facilities rather than in hardened military depots. Overall the Philippines is unlikely to contribute anything decisive to a Taiwan scenario.

Indonesia, Malaysia, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam

Indonesia, Malaysia, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam are all in either East Asia or Oceania and have some proximity to China, but they are least likely to meaningfully contribute to any U.S. coalition to defend Taiwan. Some could plausibly offer base access or even token forces, but none are likely to be active and militarily decisive allies of the U.S. in a Taiwan scenario.

Capacity

These diverse states are generally lacking in strong, expeditionary-oriented armed forces and would likely be reticent to get involved in a high-intensity superpower military clash. Let’s discuss just a few examples.

Malaysia’s armed forces have been undergoing a modest modernization program with defense spending rising from $3.7 billion to $4 billion from 2022 to 2023. Still, the focus seems to be on technological renovations rather than building up power projection capabilities at scale.94“Military modernisation to drive Malaysia defence budget at 8.4% CAGR over 2024–28,” Asia-Pacific Defence Reporter, September 28, 2023, https://asiapacificdefencereporter.com/military-modernisation-to-drive-malaysia-defence-budget-at-8-4-cagr-over-2024-28/.

Thailand, a U.S. treaty ally, has a fairly small military—spending just over 1 percent of its GDP on defense—and is limited in its reach.95“Thailand Country Commercial Guide: Defense and Security,” U.S. International Trade Administration, updated January 8, 2024, https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/thailand-defense-and-security. The extent of its force projection capability is limited to small-scale peacekeeping efforts. Fresh fissures with its backers in Washington, which supply most of its aircraft, have opened over the latter’s refusal to supply Bangkok with F-35s.96Paul Chambers, “Creating Balance: The Evolution of Thailand’s Defense Diplomacy and Defense Relations,” Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs, January–February 2024, 58–60, https://media.defense.gov/2023/Dec/05/2003352244/-1/-1/1/JIPA%20-%20CHAMBERS.PDF/JIPA%20-%20CHAMBERS.PDF.

As far as the small states of Southeast Asia are concerned, Singapore is an unusual case. The small island city-state fields a disproportionately large military. It has a modest professional corps of some 50,000 personnel but an impressive quarter million in reserves. It boasts a large and sophisticated air force with 100 modern multirole fighters, equaling those of the Royal Thai Air Force, which defends a country 13 times more populous.

But it is doubtful that Singapore can project hard power into a Taiwan war zone without U.S. support. While it does have 11 aerial tankers, which would technically allow its aircraft to range to Taiwan, its sealift capabilities are extremely limited with just four amphibious vessels and a handful of logistical ships.97Military Balance 2024, 311. Singapore’s military is structured to defend Singapore proper and the surrounding airspace and seaways on which its commercial vitality depends.

Vietnam boasts a medium-sized air force and navy, including eight Kilo-class diesel submarines imported from Russia.98Military Balance 2024, 325. Such boats could, at least in theory, be relevant to the defense of Taiwan. Papua New Guinea has been leaning in to its defense relationship with Washington by making certain potentially valuable locations available to the U.S. armed forces, as discussed below. On the other hand, it has just a few hundred personnel in its armed forces and a handful of small boats and aircraft.99Military Balance 2024, 306.

There is some possibility that in a Taiwan scenario, the U.S. might opt to respond to Chinese aggression by counter-blockading China, especially with respect to its key maritime transport nodes through Southeast Asia. In that case, basing and ISR sensors in many of the above states could become more relevant.

Willingness

Indonesia might one day wield significant military power, but for now its armed forces are mostly focused on internal security. Moreover, this large island archipelago has a strong tradition of non-alignment. While there have been occasional flare-ups in the South China Sea, Indonesia-China relations are generally in good shape, as exemplified by President Joko Widodo’s mid-2023 visit to China.100“China Open to Deepen Partnership with Indonesia, Xi Says,” Reuters, July 27, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/china-open-deepen-partnership-with-indonesia-says-xi-state-media-2023-07-27/. China and Indonesia did $133 billion in trade with each other in 2022 and Beijing is by far Indonesia’s foremost trading partner.101“Indonesia, China Getting Closer as More Beneficial Commitments Built,” Antara, January 2, 2024, https://en.antaranews.com/news/302229/indonesia-china-getting-closer-as-more-beneficial-commitments-built. Taiwan is also Indonesia’s largest destination for migrant workers. But then this, in conjunction with Indonesia’s One China policy, points to a desire to deter a Taiwan conflict rather than side with the United States in one.

Malaysia saw tensions flare with Beijing in 2021 concerning a large sortie of Chinese aircraft into the South China Sea, as well as various maritime disputes.102“South China Sea Dispute: Malaysia Accuses China of Breaching Airspace,” BBC, June 2, 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-57328868. Still, there is no hint of any interest by Kuala Lumpur in consideration of a military role in a Taiwan scenario.103“Malaysia’s New Prime Minister Talks about China-Taiwan Relations,” Commonwealth Magazine, May 18, 2018, https://english.cw.com.tw/article/article.action?id=1949. Given that Malaysia is importing major Chinese military equipment, it is unlikely to be seriously contemplating aligning against China in a military context.104Ridzwan Ramat, “Royal Malaysian Navy Receives Final Keris-class Vessel from China,” Jane’s, December 20, 2021, https://www.janes.com/defence-news/news-detail/royal-malaysian-navy-receives-final-keris-class-vessel-from-china. A fall 2023 report by the U.S. Institute of Peace suggested that Malaysia “will not take sides” in the growing superpower rivalry.105Cheng-Chwee Kuik, “Active Neutrality: Malaysia in the Middle of U.S.-China Competition,” U.S. Institute of Peace, October 2023. To access, see https://www.apln.network/news/member_activities/active-neutrality-malaysia-in-the-middle-of-u-s-china-competition.Malaysia as recently as June 2024 vocally indicated its support for Chinese sovereignty over Taiwan, further indicating it’s unlikely to help the U.S. in a conflict.106Norman Goh and Hakimie Amrie, “Malaysia reaffirms One China policy, rejects Taiwan independence,” Nikkei, June 20, 2024, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/Malaysia-reaffirms-One-China-policy-rejects-Taiwan-independence.

New Zealand and Singapore seem to invite possibilities. Wellington, like Australia, has a long history of intervening alongside American troops, but its foreign policy on the whole is more complicated than might first appear, prizing independence and pursuing good relations with Beijing.

Unlike most of the states in Southeast Asia, Singapore has a long tradition of cooperative military training with Taiwan.107I-wei Jennifer Chang, “Taiwan’s Military Ties to Singapore Targeted by China,” Global Taiwan Institute, May 6, 2020, https://globaltaiwan.org/2020/05/taiwans-military-ties-to-singapore-targeted-by-china/. It has also often followed the lead of Washington and other Western capitals, setting it apart from its Asian neighbors, for example in the Ukraine war.108Amruta Karambelkar, “Has Singapore Changed Its Stance on Ukraine?” Vivekananda International Foundation, March 16, 2023, https://www.vifindia.org/2023/march/16/has-singapore-changed-its-stance-on-ukraine. But Singapore has pursued close relations with Beijing and is a rare country where public opinion towards China runs positive.109Charissa Yong, “Global views of China remain negative, but Singapore an exception,” Straits Times, July 1, 2021, https://www.straitstimes.com/world/united-states/global-views-of-china-remain-negative-but-singapore-an-exception. While both Singapore and New Zealand have close ties to Washington, neither is an official treaty ally of the U.S. bound by a mutual defense agreement.110New Zealand is part of the “Five Eyes” intelligence sharing pact with the U.S., but the American security guarantee for New Zealand was suspended in 1986. See Amy L. Catalinac, “Why New Zealand Took Itself out of ANZUS: Observing ‘Opposition for Autonomy’ in Asymmetric Alliances,” Foreign Policy Analysis 6 (2010) 317–338.

If Singapore and New Zealand offer at least possibilities for allied coordination, that seems far-fetched with respect to Thailand. Although the U.S. formally has an alliance relationship with Thailand, this has been in a state of decay since a military coup back in 2014. Thailand is still reliant on U.S. military aid but has been enhancing its military cooperation with China; it’s also joined the Belt and Road Initiative and unlike many other East Asian nations, it has no territorial disputes with Beijing.111Christopher S. Chivvis, Scot Marciel, and Beatrix Geaghan‑Breiner, “Thailand in the Emerging World Order,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, October 26, 2023, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2023/10/thailand-in-the-emerging-world-order?lang=en.

Finally, there is Vietnam, which has by far the most formidable military of all these Southeast Asian countries. Hanoi has occasionally made clear that it will not bend to Chinese threats, and its relations with the United States have improved in recent years. In mid-2023, the USS Ronald Reagan carrier strike group made a visit to Vietnam, the third American carrier to do so since 2018.112Askia Collins (USN), “Ronald Reagan Strike Group Visits Vietnam,” U.S. Pacific Fleet, June 25, 2023, https://www.c7f.navy.mil/Media/News/Display/Article/3438275/uss-ronald-reagan-carrier-strike-group-visits-vietnam/. Notably, at nearly the same time, the Vietnamese and Chinese navies conducted their thirty-fourth joint maritime patrol of the Gulf of Tonkin.113“The Chinese and Vietnamese militaries launched the 34th joint patrol in the Beibu Gulf” [中越两军开展第34次北部湾联合巡逻], PLA Daily [解放军报], June 28, 2023, http://www.81.cn/szb_223187/szbxq/index.html?paperName=jfjb&paperDate=2023-06-28&paperNumber=04&articleid=908998, 4.

Yet Hanoi is not eager to pick sides among the two superpowers.114On Vietnam’s Four No’s, see “‘Four No’s’ Principle of National Defense Policy,” Socialist Republic of Viet Nam News, January 26, 2020, https://en.baochinhphu.vn/four-nos-principle-of-national-defense-policy-11137244.htm. This reticence can be seen in its official policy called the “four no’s”: no military alliances; no siding with one country over another; no foreign military bases or use of Vietnamese territory to oppose other countries; and no use of force or threats to use force in international relations. Given this tradition, it is difficult to see Vietnam getting involved in a Taiwan scenario. Additionally, from a military standpoint, Vietnam is quite vulnerable to Chinese coercion, not least because its capital is only about 100 miles from the Chinese mainland. Hanoi may consequently focus on the sensitive South China Sea issue but will probably not align closely with Washington nor seek a role on Taiwan.

Analysis

The prospects for meaningful assistance from these countries are bleak. The two with the geopolitical heft to develop into genuine middle-rank military powers, Indonesia and Vietnam, show little disposition to get involved in a Taiwan scenario. It’s worth noting that nearly all states in the Asia-Pacific consistently affirm the One China policy as a precondition of stable relations with Beijing.115See, for example, “Việt Nam persistently follows ‘One China’ policy: Spokeswoman,” Vietnam News, January 15, 2024, https://vietnamnews.vn/politics-laws/1639231/viet-nam-persistently-follows-one-china-policy-spokeswoman.html; Norman Goh and Hakimie Amrie, “Malaysia Reaffirms One China Policy, Rejects Taiwan Independence,” Nikkei Asia, June 20, 2024, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/Malaysia-reaffirms-One-China-policy-rejects-Taiwan-independence; Kelvin Chen, “Taiwan Rejects Indonesia’s Acceptance of ‘One China’ Principle,” Taiwan News, November 11, 2024, https://taiwannews.com.tw/news/5968903.

It is true that among some of these countries are pockets of excellence that could prove useful in a Taiwan scenario, whether New Zealand’s new squadron of advanced P-8 anti-submarine aircraft or a couple dozen Singaporean F-15 fighters. Still, those numbers are quite small in the larger scope of this hypothetical war, and many of these countries simply have other priorities. For example, Singapore has the most technologically advanced, well-drilled, and expeditionary military on this list, but the main reason for this is that Singapore is surrounded by much bigger and sometimes unstable neighbors.116See, for example, Dan Slater, “The Ironies of Instability in Indonesia,” Social Analysis: The International Journal of Social and Cultural Practice 50, no. 1 (2006) http://www.jstor.org/stable/23181954, 208–13. This logical prioritization of homeland security could prevent Singapore from actively sending its forces into a Taiwan conflict.

That may partially explain why the U.S. is now working on developing six bases in Papua New Guinea. It seems the Pentagon views that country’s geography as favorable.117Zach Abdi, “U.S. Set to Expand Naval Base in Papua New Guinea,” USNI News, April 6, 2024, https://news.usni.org/2024/04/06/u-s-set-to-expand-naval-base-in-papua-new-guinea. Yet that seems a questionable assumption given that Papua New Guinea is well over 2,000 miles from Taiwan, even more distant than Guam. Moreover, it is less than 200 miles from Australia, raising a significant question of redundancy.

Nevertheless, the geographical value of many of these states, including Papua New Guinea, could increase in two variations of the Taiwan scenario. First, it is conceivable that a U.S. response to a Chinese invasion of Taiwan could involve attempting to blockade Chinese shipping, as mentioned above, especially in and around the Strait of Malacca. Second, as the AUKUS nuclear submarine deal develops further, one can anticipate both U.S. and Australian nuclear submarines surging north in a wartime scenario. In that case, the security of the maritime chokepoints north of Australia, as discussed above, could become more important. It is noteworthy that Jakarta has not embraced the AUKUS submarine deal with enthusiasm, to put it mildly, and some Western strategists are even worried Indonesia could pose problems for the agreement’s implementation.118Dita Liliansa, “Could Indonesia Legally Stop Transit by Nuclear-powered AUKUS Subs?” Interpreter, Lowy Institute, March 21, 2023, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/could-indonesia-legally-stop-transit-nuclear-powered-aukus-subs.

Europe