Key points

- NATO membership for Ukraine is infeasible for a number of reasons, not least questions of defensibility. The alliance and the United States should therefore abandon their public position supporting Ukraine’s eventual membership.

- Removing NATO membership from the discussion would force Ukraine to focus on more realistic options such as neutrality. In addition to helping decrease tensions with Russia, formal non-alignment would also allow Ukraine to focus on internal challenges, like corruption and economic reform.

- Ukraine’s ability to manage its external affairs is dictated by its physical location. The challenge for Kyiv is to craft an approach that acknowledges these limits and finds a balance between the contending pulls of east (Russia) and west (Europe).

- U.S. policy should prioritize the minimization of direct conflict with Russia over Ukraine. The United States has no vital interest in Ukraine that would warrant war with a nuclear power.

Defining interests

The wounds from the crisis that beset Ukraine in early 2014 remain fresh. Russia has consolidated its hold over Crimea. Meanwhile the Donbas insurgency continues to simmer, having claimed more than 14,000 lives over the past six years.1Robyn Dixon and Natalie Gryvnyak, “Ukraine’s Zelensky Wants to End a War in the East. His Problem: No One Agrees How to Do It,” The Washington Post, March 19, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/ukraines-zelensky-wants-to-end-a-war-in-the-east-his-problem-no-one-agrees-how-to-do-it/2020/03/19/ae653cbc-6399-11ea-8a8e-5c5336b32760_story.html. At the root of Ukraine’s recent troubles are moments when the country was perceived as facing a civilizational choice between east and west.2John Lloyd, “In Ukraine, a Choice of Civilizations,” Reuters, October 17, 2013. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-lloyd-ukraine/column-in-ukraine-a-choice-of-civilizations-idUSBRE99G0RE20131017.

Geography is destiny for Ukraine

Ukraine must live within the politics of its geography. Kyiv’s ability to manage its foreign affairs is largely dictated by the country’s location.

The prospect of a definitive move one way or the other—toward NATO and the European Union (EU) or firmly back into Russia’s orbit—has stressed Ukraine’s internal stability. This was the case when pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovych voided an economic association agreement with the EU in favor of Russia’s Eurasian Economic Union. The result was the Euromaidan protests and the ensuing violence and lawlessness that engulfed parts of Ukraine, leading to Yanukovych’s ouster and Russian aggression.3Gerard Toal, Near Abroad, New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2017, 211–212, 288.

There remains significant—though not universal—sentiment among the Ukrainian population for greater ties to Europe and the United States. There are also equally strong elements within Ukraine that seek closer relations with Russia.4Gerard Toal, John O’Loughlin, and Kristen M. Bakke, “Is Ukraine Caught between Europe and Russia? We Asked Ukrainians This Important Question,” The Washington Post, February 26, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/02/26/is-ukraine-caught-between-europe-russia-we-asked-ukrainians-this-important-question/. Even as Ukraine tries to master this delicate internal balance, it must also accept that its unique geographic position will define the limits of its external relationships. For Kyiv, there is no escaping Moscow’s strategic gaze and influence. Ukraine must live within the politics of its geography.

For the United States, the challenge is determining what its interests in Ukraine are and how far it is willing to go to pursue them. As political scientist Barry Posen argues, the United States does not have a vital interest in Ukraine, i.e., one worth sending its troops to kill and die for.5Barry R. Posen, “Ukraine: Part of America’s ‘Vital Interests’?” The National Interest, May 12, 2014. https://nationalinterest.org/feature/ukraine-part-americas-vital-interests-10443. Even those most empathetic to Ukraine’s trans-Atlantic ambitions would balk at the prospect of fighting a war with Russia over them. Indeed, if the United States does have a vital interest here, it is precisely that: to avoid differences over Ukraine resulting in open conflict with Russia. Danger mitigation should be America’s guiding principle.

But the United States also has a general (if secondary) interest in stability in Eastern Europe writ large. A stable Ukraine at peace—internally and with its neighbors—is essential to attaining that. To the extent it reasonably can, the United States should use its influence to help Ukraine tread the path between the contending pulls on its society in order to maintain that stability. In terms of external security relationships, this ultimately should lead to Ukraine adopting some form of non-alignment or neutrality as the basis for its foreign and defense policies.

An essential step in this process is for the United States to formally put an end to the prospect of NATO membership for Ukraine. As will be discussed below, while numerous factors preclude Ukraine from realistically being incorporated into the alliance, the sustained false hope of NATO membership discourages Ukraine from examining more pragmatic and necessary options.

A compelling case

It is easy to be sympathetic to Ukraine’s plight. Few areas of the world suffered more in the twentieth century than the territory of modern Ukraine. From the Holodomor to some of the fiercest battles of World War II to the Chernobyl nuclear accident, the Ukrainian people have repeatedly endured terrible hardship.

Over the past 30 years, Ukraine has also had at least two major, positive impacts on U.S. security. Most Americans today might not know the name “Rukh,” but that Ukrainian independence movement—along with its counterparts in the Baltic states—was a catalyst for the final collapse of the Soviet Union.6For a thorough discussion on Ukraine’s path to independence and Rukh’s role, see Bohdan Nahaylo, The Ukrainian Resurgence, Toronto and Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1999. For an excellent account of the Baltic independence movements see Anatol Lieven, The Baltic Revolution: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and the Path to Independence, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1993. Then after the Cold War’s end, Ukraine voluntarily relinquished more than 4,000 tactical and strategic nuclear warheads it had inherited from the USSR in the single greatest instance of denuclearization since the dawn of the atomic era.7Steven Pifer, The Trilateral Process: The United States, Ukraine, Russia and Nuclear Weapons, Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, May 2011, 4.

Ukraine surrendered its nuclear weapons in part because it received assurances from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Russia that its territorial integrity would be respected. This pledge was encoded in the Budapest Memorandum, a diplomatic agreement signed by all four states in 1994.8For full text, see “Annex I: Memorandum on Security Assurances in Connection with Ukraine’s Accession to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons,” contained in “Letter dated 7 December 1994 from the Permanent Representatives of the Russian Federation, Ukraine, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the United States of America to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General,” http://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/s_1994_1399.pdf. However, the document is not a formal treaty, with no provisions compelling any outside state to protect Ukraine from attack (similar, for example, to NATO’s Article 5 commitment).9See Cody M. Poplin and Benjamin Bissell, “Throwback Thursday: The 1994 Budapest Memorandum,” Lawfare, November 20, 2014, https://www.lawfareblog.com/throwback-thursday-1994-budapest-memorandum, and Ron Synovitz, “Explainer: The Budapest Memorandum and Its Relevance to Crimea,” Radio Free Europe, February 28, 2014, https://www.rferl.org/a/ukraine-explainer-budapest-memorandum/25280502.html. Still, the absence of action by the United States in the face of Russia’s aggression has added sympathy to the Ukrainian cause among those who believe Washington essentially abandoned Kyiv in its hour of need.

Well before 2014, compassion for the Ukrainian cause led some in the United States to advocate for its eventual entry into NATO. President George W. Bush, for example, saw offers of NATO membership to Ukraine and Georgia as keeping with broader support to emerging democracies under his “Freedom Agenda.”10The Freedom Agenda was the name given to the Bush administration’s post-9/11 strategic vision, which linked American security with the promotion of liberty abroad. Bush’s second inaugural address is considered to be the clearest enunciation of this approach to world affairs. For a transcript, see National Public Radio, “President Bush’s Second Inaugural Address,” January 20, 2005. https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=4460172. To this end, he lobbied hard for Membership Action Plans (MAPs)—i.e., specific military-technical roadmaps for admission into the alliance—to be extended to both states at the 2008 NATO Summit in Bucharest.11Toal, Near Abroad, 94–95. Resistance from European allies—most prominently France and Germany—led to NATO demurring on the issue of MAPs.12Steven Erlanger and Steven Lee Myers, “NATO Allies Oppose Bush on Georgia and Ukraine,” The New York Times, April 3, 2008. https://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/03/world/europe/03nato.html. But the summit’s communique did include an unambiguous statement that Ukraine and Georgia would become NATO members, albeit without specifying a timetable for this to occur.13Section 23 of the Bucharest Summit Declaration states, “NATO welcomes Ukraine’s and Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic aspirations for membership in NATO. We agreed today that these countries will become members of NATO.” See North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “Bucharest Summit Declaration,” Issued by the Heads of State and Government participating in the meeting of the North Atlantic Council in Bucharest on 3 April 2008.https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/official_texts_8443.htm.

Russia’s annexation of Crimea added a new dimension to calls of support for Ukrainian sovereignty and independence. At the time, Russia’s actions were routinely compared by many commentators to Nazi Germany’s seizure of the Sudetenland in 1938.14See, for example, the comments by Canadian Foreign Minister John Baird in Simona Kralova, “Crimea Seen as ‘Hitler-style’ Land Grab,” BBC News, March 14, 2014, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-26488652; remarks by the German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble in “German Minister Compares Putin’s Ukraine Moves to Hitler in 1938,” Reuters, March 31, 2014, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-ukraine-russia-germany/german-minister-compares-putins-ukraine-moves-to-hitler-in-1938-idUSBREA2U0S420140331; the editorial by Estonian President Toomas Hendrik Ilves, “The United States and Europe Need a New Rulebook for Russia,” Washington Post, March 27, 2014, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/toomas-hendrik-ilves-the-united-states-and-europe-need-a-new-rulebook-for-russia/2014/03/27/e15dad62-b5bb-11e3-8020-b2d790b3c9e1_story.html; and the op-ed by former Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvilli, “The West Must Not Appease Putin,” Washington Post, March 6, 2014, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/mikheil-saakashvili-the-west-must-not-appease-putin/2014/03/06/db9e0c82-a4a9-11e3-8466-d34c451760b9_story.html. The implications of the analogy were clear: this was the first step of many if Russia was left unchecked—if the West, essentially, “appeased” the government of Vladimir Putin in a “second Munich.” This argument grew to even greater intensity as military aid to Ukraine became entangled with the impeachment proceedings against President Trump, with one former member of the National Security Council arguing that such aid was needed to effectively help the Ukrainians “fight Russia over there, so we don’t have to fight Russia here.”15Timothy Morrison, former Senior Director for Europe and Russia, National Security Council, as quoted in House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, The Trump-Ukraine Impeachment Inquiry Report, December 2019, 18. https://intelligence.house.gov/uploadedfiles/the_trump-ukraine_impeachment_inquiry_report.pdf. More serious questions about whether Russia actually had the means or intentions for such action were left unexamined.

Ukraine conflict zones

The conflict in Ukraine that started in early 2014 remains unresolved today. Russia still controls Crimea, and hostilities continue in the Donbas.

Whether the impetus has been democratic empathy or fevered concerns about Russian aggression, the result of thirty years of U.S. policy debate is an official commitment to Ukraine’s eventual entry into NATO. Admittedly, both the Obama and Trump administrations have been less ardent in their direct support of this goal than Bush, but neither did they ever formally reverse the stance. As recently as January 2020, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo publicly averred continued U.S. support for Ukraine joining the alliance on a visit to Kyiv.16“Secretary Michael R. Pompeo and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy at a Press Availability,” U.S. Embassy in Ukraine, January 31, 2020. https://ua.usembassy.gov/secretary-michael-r-pompeo-and-ukrainian-president-volodymyr-zelenskyy/.

From NATO’s perspective, there likewise has never been an official reversal of the Bucharest Declaration. Despite lukewarm sentiments among some European allies, NATO’s public position remains that Ukraine and Georgia will eventually be in the alliance. In April 2020, NATO foreign ministers approved a package of measures to further enhance cooperation between the alliance and both states, including the sharing of radar data.17“Press Conference by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg Following the Meeting of NATO Ministers of Foreign Affairs,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, April 2, 2020. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/opinions_174772.htm.

NATO’s new reality

Despite the persistence of U.S. and NATO policy in support of Ukrainian membership, legitimate doubts should be raised about its wisdom. At least four factors make this so.

Lack of true consensus among the Ukrainian people about joining NATO

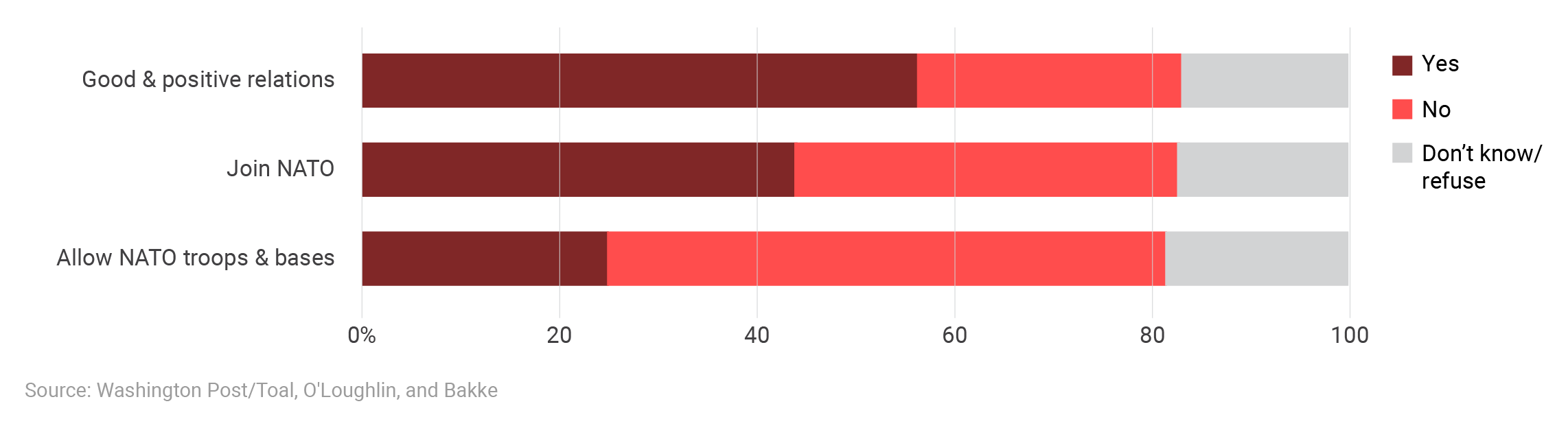

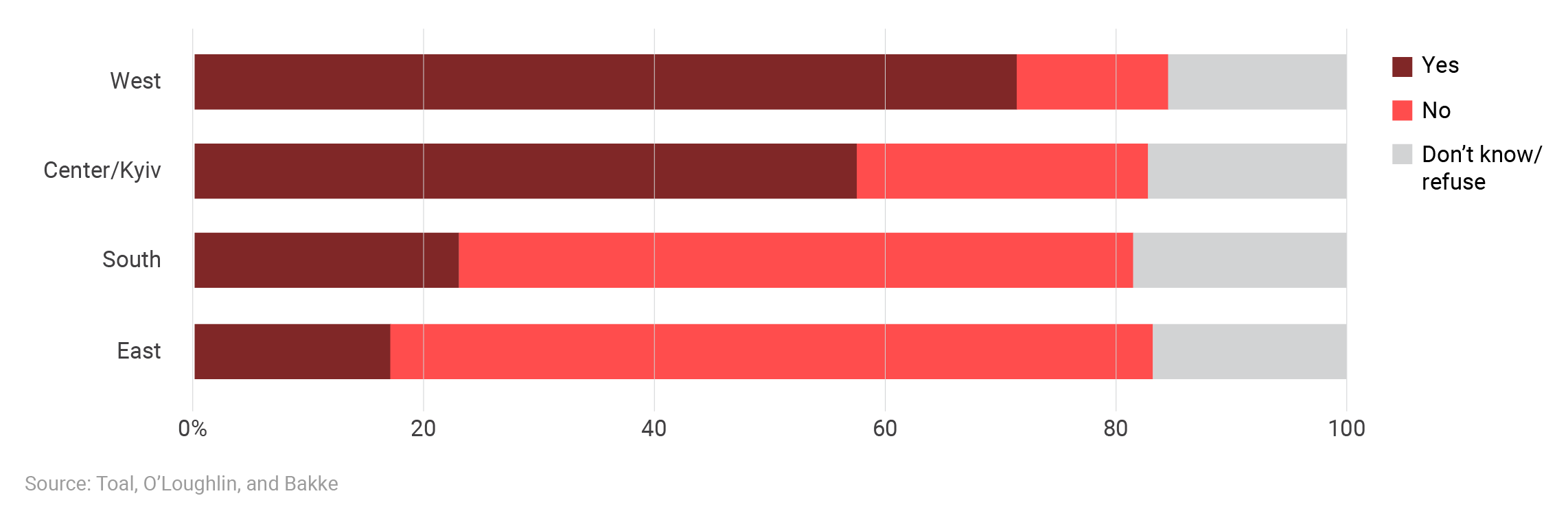

The first of these is the lack of true consensus among the Ukrainian people on the desirability of joining the alliance. A recent study by academics Gerard Toal, John O’Loughlin, and Kristen M. Bakke provides new light on current attitudes within Ukraine toward its external relations. Overall, less than half (44 percent) of those surveyed were found to be in favor of joining NATO and only 25 percent supported permitting the alliance to base forces on their territory.18Toal, O’Loughlin, and Bakke, “Is Ukraine Caught between Europe and Russia?” Breaking the country down into four macro-regions—West, Central, South, and East—the survey found a regionally inverted opinion on the question of NATO membership: As many people in the West and Central (including Kyiv) were supportive of joining the alliance as were opposed to that proposition in the East and South.19See the chart, “Support for Military Relations in Ukraine by macro region,” from Toal, O’Loughlin, and Bakke’s research. The figure has not been officially published but was shared on Twitter by Toal as part of a thread explicating the information contained in “Is Ukraine Caught between Europe and Russia?” Gerard Toal, Twitter post, February 26, 2020, 9:54 a.m. https://twitter.com/Toal_CritGeo/status/1232680229480562688/photo/1.

Ukrainian views of military relations with NATO

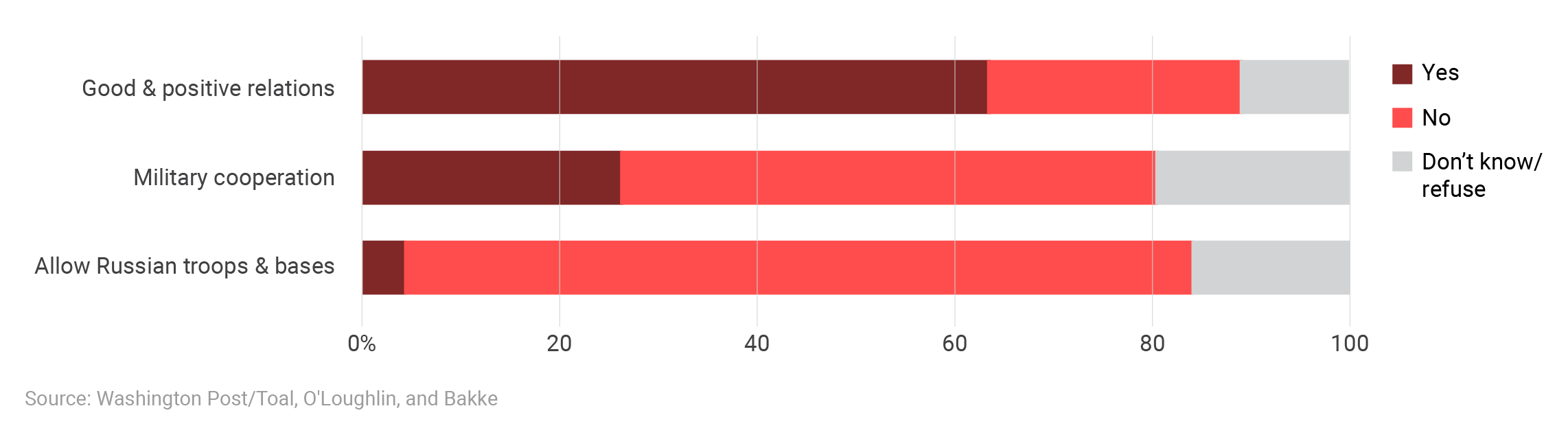

Ukrainian views of military relations with Russia

Among Ukrainians, 44 percent support joining NATO, and 26 percent support military cooperation with Russia; 25 percent would permit NATO troops and bases in Ukraine, while 4 percent would allow Russian troops and bases.

Ukraine has done a better job maintaining its internal cohesion than many expected—including the U.S. intelligence community—immediately after it attained independence.20In 1993, for example, the CIA produced an analysis predicting Ukraine’s eventual cleavage along east-west lines. See Daniel Williams and R. Jeffrey Smith. “U.S. Intelligence Sees Economic Plight Leading to the Breakup of Ukraine,” Washington Post, January 15, 1994. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1994/01/25/us-intelligence-sees-economic-plight-leading-to-breakup-of-ukraine/48282f8d-0fe9-457f-b252-39d98137c003/. But incorporation into NATO without much stronger—and geographically dispersed—domestic backing could place unneeded stress on Ukrainian society. It would also go against NATO’s own standards requiring high internal support for joining the alliance as a criterion for membership.

Changing strategic landscape in Europe

Second, the strategic setting in Central and Eastern Europe has changed significantly since earlier rounds of NATO enlargement. Russia has regained its status as a legitimate military player—at least at the regional level. Since the nadir of the 1990s, Russia has substantially rebuilt its conventional forces; it further used its shaky performance in the August 2008 war against Georgia as an impetus to improve its operational concepts while continuing to modernize its force structure.21Michael Kofman, “Russian Performance in the Russo-Georgian War Revisited,” War on the Rocks, September 4, 2018. https://warontherocks.com/2018/09/russian-performance-in-the-russo-georgian-war-revisited/.

When NATO admitted the Baltic states in 2004 and the Visegrad countries (including Poland) in 1999, Russia’s response was limited to the realm of diplomacy because it couldn’t use military means to object. Today, Russia’s reaction to Ukrainian membership in NATO could take on a more concrete and hostile form, from an intensification of support for the Donbas insurgency to additional aggression against Ukrainian territory, through covert or overt means. The reality is that the window when Ukraine safely could have been admitted into NATO is now closed.

Defensibility of Ukraine

A third factor relates to the first two. Even assuming Ukraine could be admitted into NATO, it would present imposing questions of defensibility. In earlier rounds of enlargement, practical questions about defense often took a backseat to other matters, such as trans-Atlantic integration and the perceived benefits for strengthening democracy in Central and Eastern Europe. The relatively benign security environment and deep disparity in U.S. and Russian conventional forces at the time made this possible. But with Russia’s return as a capable regional military player, avoiding such questions vis-à-vis Ukraine’s membership is not an option.

It would be negligent of the U.S. to admit Ukraine into NATO without a clear idea for how its 1,200 mile-border with Russia would be defended, short of total reliance on the threat of nuclear war—a dangerous and outdated strategy. This point can’t be emphasized enough: NATO would need to defend a frontier that’s roughly equal to the distance between New York City and Miami.

Ukrainian views of joining NATO by macro-region

Western and central Ukrainians seek closer ties with the West and largely support joining NATO. Ukrainians in the south and east seek closer ties with Russia and largely oppose joining NATO.

Outside of Russia itself, Ukraine is the largest country in Europe by land area. Defending it against its immediate neighbor would almost certainly require basing some NATO forces permanently on Ukrainian territory. As the earlier opinion poll indicates, this is likely to be unacceptable to the majority of Ukrainians (including some who support alliance membership).

Moreover, the basing of U.S. or other foreign forces on Ukraine’s territory would also be anathema to Russia. The basic dilemma is this: It would be hard for NATO to adequately defend Ukraine without committing forces of such size and proximity that Russia itself would have to view them with intense concern for its own security. Adding Ukraine puts NATO’s main frontier within 300 miles of Moscow.

An imbalance of interests between the West and Russia

This points to the final factor that makes Ukrainian NATO membership next to impossible: the disparity in interests between the West and Russia that colors all interactions over Ukraine. Ukraine is unlike any other territory that NATO could add. It is not only intimately tied up with Russian history—with many Russians regarding parts of the modern Ukrainian state as Russia proper—but it also sits astride the traditional routes invaders have exploited to attack Russia for centuries.22Nicholas V. Riasanovsky, A History of Russia, New York and Oxford; Oxford University Press, 1984, 23–60.

Ukraine in NATO is a policy option for the United States; for Russia, it seems like an existential threat. It’s reckless to suggest Russia would accept Ukrainian membership in the alliance without some kind of dangerous counter-reaction involving covert or overt use of force.

Attempting to put Ukraine in the alliance might be the worst possible thing for it. More than likely, the only circumstances that would responsibly allow for Ukraine to enter NATO would be the same ones that would obviate its necessity: if Russia were to undergo a genuine and stable democratic transformation organically, leading to a radical reassessment of its relationships with neighboring states. But banking on that is not feasible from a defense planning perspective.

Russia is an illiberal, authoritarian regime and is likely to remain so for the foreseeable future. America, NATO, and Ukraine need to deal with that reality accordingly. If this is the case, serious doubts must be raised about the United States continuing to publicly support Ukrainian membership in the alliance. It serves no effective purpose; worse, it might close off avenues of strategic thought that could better support Ukrainian security interests long term.

As a victim of geography, neutrality is Ukraine’s best option

With the collapse of the Soviet Union and NATO’s subsequent expansion, Ukraine has inherited from Poland the role of Europe’s reigning victim of geography. For more than two centuries, Poland and its status (or lack thereof) as an independent state were at the heart of multiple European wars.23Norman Davies, God’s Playground, Vol. 2: 1795 to the Present, New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1982. Ukraine now has the misfortune to be the epicenter of tensions between Russia and the West.

For the United States, its overriding security interest is danger mitigation; the absence of direct conflict with Russia over Ukraine should be the priority and not the “Ukrainian cause,” no matter how much empathy it might engender. Stabilizing Ukraine in a security arrangement that meets this goal should be the focus of U.S. policy rather than continuing support for an implausible membership in NATO.

Ukraine must recognize its choices with regard to its external security relationships may not always be entirely its own. It also needs to find a balance that satisfies those segments of its population with opposing views on where Ukraine’s orientation should lie, east or west. Just as there is a domestic constituency opposed to NATO membership, there also is a large segment that sees “non-alignment” as a codeword for default subjugation to Russia. That the policy of neutrality was most closely associated in recent years with the ousted President Yanukovych—who was widely perceived as “Putin’s man”—only reinforces this position.

There are significant portions of the Ukrainian population that legitimately view their country and ethnicity as distinct from Russia. An arrangement that forced them back under Moscow’s rule—be it direct or, more likely, indirect—would spark severe internal cleavage along regional lines, with the west and central parts of the country aligning against the east and south.

Admittedly, this is an extreme possibility, but it underscores how Ukraine can be a source of regional instability through internal strife, as well as a source of conflict for external powers. The Donbas is a relatively small war from a geographic standpoint, yet its carnage has been significant. It is daunting to contemplate a larger conflict on Ukrainian territory.

This will be a difficult path for Ukraine to walk. That said, removing the option of NATO membership could force a more constructive internal dialogue within Ukraine on what its status might look like under some concept of political and military non-alignment.24For an overview of Ukrainian neutrality since its independence and alternative European models, see the draft research paper by Viktoria Potapkina, “Ukrainian Neutrality: Myth or Reality?” November 30, 2010, available via E-International Relations Students: https://www.e-ir.info/2010/11/30/ukraine%e2%80%99s-neutrality-a-myth-or-reality/ So long as membership in the alliance is officially on the table, this debate is unlikely to occur as deeply and fully as it should.

Finlandization?

But what form should that neutrality take? Within the foreign policy community, two models have been routinely proffered for Ukraine: Austria and Finland. Finland is the one most frequently cited. Following Russia’s seizure of Crimea, for example, Zbigniew Brzezinski and Henry Kissinger both called for this option to be given serious consideration.25Zbigniew Brzezinski, “Russia Needs a ‘Finland Option’ for Ukraine,” Financial Times, February 23, 2014. https://www.ft.com/content/7f722496-9c86-11e3-b535-00144feab7de, and Henry Kissinger, “To Settle the Ukraine Crisis Start at the End,” The Washington Post, March 5, 2014. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/henry-kissinger-to-settle-the-ukraine-crisis-start-at-the-end/2014/03/05/46dad868-a496-11e3-8466-d34c451760b9_story.html. “Finlandization” has since become shorthand for Ukrainian neutrality among those advocating alternatives to NATO membership. However, this concept is largely based on a romanticized reading of Finland’s Cold War history.

In 1948, Helsinki signed the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance (FCMA) with Moscow. It allowed Finland to remain free of Soviet forces (from 1956 onward), unlike the Soviet Union’s other western neighbors, all of whom were incorporated into the Warsaw Pact military alliance. But Finland was hardly independent. “Neutrality” was a fig leaf for kowtowing to Moscow politically in exchange for preserving some internal sovereignty and a relatively free hand to conduct its external economic affairs.26Charles M. Perry, Michael J. Sweeney, and Andrew C. Winner, Strategic Dynamics in the Nordic-Baltic Region: Implications for U.S. Policy. Dulles, VA: Brassey’s, 2000, 123. Even this didn’t stop occasional and explicit interference by the Soviets, such as the 1961 Note Crisis, when Moscow directly influenced the Finnish presidential election.27Arne Olav Brundtland, “Nordic Security at the End of the Cold War: Old Legacies and New Challenges,” in Nordic-Baltic Security: An International Perspective, eds. Arne Olav Brundtland and Don M. Snider, Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 1994, 9.

The Note Crisis was prompted by the possibility the sitting president, Urho Kekkonen, might lose the upcoming election to Olavi Honka, a social democrat who had split from the Finnish communist party. Moscow threatened to invoke a clause in the FCMA allowing for “military cooperation,” i.e. the reintroduction of Red Army forces onto Finnish territory. The Soviets in essence threatened invasion. Honka withdrew, and Kekkonen went on to win re-election—four more times.28“Domestic Developments and Foreign Politics, 1948-66,” in Finland: A Country Study, eds. Eric Solsten and Sandra W. Meditz, Washington, DC: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1988. http://countrystudies.us/finland/25.htm. He served as Finland’s president up until 1981, reigning as a low-grade autocrat who was seen as “Moscow’s man.”29Ed Dutton, “Playing the Blame Game: Finland & the Soviets,” History Today 58, no. 10, October 2009. https://www.historytoday.com/archive/playing-blame-game-finland-soviets.

There’s a ready comparison to be made between Kekkonen and the ousted Yanukovych. Yanukovych was openly supported by Putin in Ukraine’s 2010 presidential election, winning a close, controversial contest. His victory was seen as solidifying Russia’s influence in Ukraine, symbolized by Yanukovych’s subsequent abrogation of Ukraine’s association agreement with the EU in deference to an economic pact with Russia. But that move set off the Euromaidan protests, unleashing not only anarchy in parts of Ukraine, but also precipitating Russia’s seizure of Crimea.

This highlights the internal danger of the wrong type of neutrality being foisted on Ukraine. Prescribing “Finlandization” now for Ukraine is to consign it essentially to the status of a vassal state, one which could again carry unwanted implications for its internal cohesion. It would be resisted strongly in many parts of the country, especially the western regions and the central area around Kyiv. Ukraine’s internal stability should be weighed with external concerns—not out of simple deference to Ukrainian wishes but because domestic discord can be as destabilizing to the region as external conflict.

The Austrian model

The Austrian model offers a more interesting choice.30See Franz-Stefan Gady, “Austrian Neutrality: A Model for Ukraine,” The National Interest, March 6, 2014. https://nationalinterest.org/commentary/austrian-neutrality-model-ukraine-10005?page=0%2C1, and Douglas Macgregor, “The Ukrainian State Treaty: An Offer Putin Can’t Refuse,” Foreign Policy, August 1, 2016. https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/08/01/the-ukrainian-state-treaty-an-offer-putin-cant-refuse-russia-nato-ukraine/. Austria enjoyed more true independence than Finland during the Cold War, aided in part by the lack of a contiguous border with the Soviet Union. Moreover, the approach Austria took—a multilateral treaty with other powers, including the United States—differed markedly from the bilateral FMCA signed between Helsinki and Moscow. That Austria surrendered territory—the province of South Tyrol—as part of its neutrality bargain is another reason contemporary writers have latched onto this example; Ukraine sanctioning the loss of Crimea may well be a price it has to pay for a more constructive relationship with Russia.31Gady, “Austrian Neutrality: A Model for Ukraine.”

But, while on the surface the Austrian model holds promise, the unique circumstances under which it was initiated and signed—as a defeated and occupied combatant after World War II—are far from an exact match to Ukraine’s current situation. Also, rather than being something imposed on Austria—as a similar treaty would be on Ukraine—neutrality was a solution engineered by the Austrians themselves.32“The 1955 State Treaty and Austrian Neutrality,” in Austria: A Country Study, ed. Eric Solsten, Washington, DC: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1994. http://countrystudies.us/austria/47.htm. Indeed, the Eisenhower administration initially opposed the move at the time, worrying Austrian neutrality would weaken the West and perhaps set an unwanted precedent for Germany.33Gunter Bischof, “Eisenhower and the Austrian Treaty,” in Eisenhower: A Centenary Assessment, eds. Gunter Bischof and Stephen E. Ambrose, Baton Rouge and London: LSU Press, 1995, 148–149.

In contrast, the actions of Ukraine’s political establishment—at least since the seizure of Crimea—have been to tack in the opposite direction of non-alignment. In December 2014, the Ukrainian parliament voted to formally abandon the “non-bloc” status promoted during Yanukovych’s tenure. The then-Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko called the legislation “a bill about our place in Western civilization.”34“Ukraine Votes to Abandon Neutrality, Set Sights On NATO,” Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty, December 23, 2014. https://www.rferl.org/a/ukraine-parliament-abandons-neutrality/26758725.html. In short, whereas Austrian political elites viewed non-alignment as their path to security from Soviet occupation, many of their contemporary Ukrainian counterparts often view it as the road to Russian subjugation.

There is, admittedly, modest hope greater support might be growing among the Ukrainian polity for non-alignment. The aforementioned survey of Ukrainian attitudes toward its external relationships found a slim majority (50.4 percent) supporting some form of neutrality.35Toal, O’Loughlin, and Bakke, “Is Ukraine Caught between Europe and Russia?” That figure is far from decisive, though, and, as yet, is not widely reflected in Ukrainian political elites, many of whom still pin their hopes on eventual entry into NATO.36Following his recent appointment, Defense Minister Andriy Taran suggested Ukraine attaining military compatibility with NATO—likely a prerequisite for entry into the alliance—was not truly realistic, calling the goal “ambitious but unachievable.” While his comments didn’t explicitly rule out Ukraine joining NATO, it acknowledged some of the concrete challenges that process would entail. It predictably provoked a harsh response from alliance advocates within Ukrainian policy circles—and a subsequent retraction. See Tetiana Gaiduk, “Does Zelensky’s Ukraine Still Want to Join NATO?” The Atlantic Council, April 13, 2020, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/does-zelenskyys-ukraine-still-want-to-join-nato/, and Ilya Timtchenko, “Which Way Will Ukraine Swing?” Foreign Policy, May 20, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/05/20/ukraine-zelensky-corruption-russia-european-union/.

A Swedish alternative?

Sweden offers a more appealing representation for Ukraine. Like Austria, Swedish neutrality was a deliberate, internal choice. In Sweden’s case it resulted from its catastrophic defeats during the Napoleonic Wars.37For a more fulsome discussion of the history of Swedish neutrality and non-alignment, see John Logue, “The Legacy of Swedish Neutrality,” in The Committed Neutral: Swedish Foreign Policy, ed. Bengt Sundelius, London and New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 1989. Kindle Edition. What’s relevant to the Ukrainian experience is non-alignment gave Sweden time to recover from its national trauma and redevelop as a viable political and economic power in its own right. While one can debate the morality of it, neutrality also allowed Sweden to avoid the worst of subsequent European conflagrations, such as both world wars. In a similar light, neutrality could not only serve Ukraine vis-à-vis assuaging Russian security concerns, but also by giving the still relatively young nation time to consolidate itself internally.

The more successful Ukraine grows as a state, the better it will be able to withstand external pressure and coercion from its eastern neighbor. Ultimately, what will best protect Ukraine against Russian interference and manipulation will be its ability to provide its people with effective governance and opportunities to attain their own prosperity. An analog can be seen in Estonia and Latvia, where the Russophone community has consistently resisted Moscow’s “soft power,” despite having differences at times with the eponymous nationalities in their countries. The better economic prospects found in these nations (including access to the European Union) has helped inoculate their Russophone communities against external influence.38See, for example, Kristian Nielsen and Heiko Paabo, “How Russian Soft Power Fails in Estonia: Or, Why the Russophone Minorities Remain Quiescent,” The Journal of Baltic Security 1, no. 2, 2015: 125–57. https://content.sciendo.com/view/journals/jobs/1/2/article-p125.xml.

Ukraine is a nation of over 40 million people which conceivably could become a leading European state someday—if it can curb its endemic corruption and grow its economy.39For a broader discussion, see Cynthia Buckley, Ralph Clem, and Erik Herron, “How to Stabilize Ukraine Long Term? Securitize Well-Being,” War on the Rocks, December 4, 2019. https://warontherocks.com/2019/12/how-to-stabilize-ukraine-long-term-securitize-well-being/. Since 2014, the governments of Volodymyr Zelensky and his predecessor, Petro Poroshenko, have attempted to tackle these interlinked challenges with mixed results. On the positive side, Poroshenko is credited with curbing the nation’s debt and average wages have also more than doubled since 2016.40Anders Aslund, “Ukraine’s Underrated Economy Is Poised for a Strong 2020,” The Atlantic Council, January 6, 2020. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/ukraines-underrated-economy-is-poised-for-a-strong-2020/. The association agreement with the European Union has been resuscitated, entering into effect in 2017. But Ukraine remains the poorest country in Europe on a per capita basis having surpassed Moldova for that dubious distinction in 2019.41Anders Aslund, “What Is Wrong with the Ukrainian Economy?” The Atlantic Council, April 26, 2019. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/what-is-wrong-with-the-ukrainian-economy/. Additional structural reforms are badly needed—especially in the banking sector—while graft and corruption remain unwelcome facts of life.42Aslund, “What is Wrong with the Ukrainian Economy,” and Timtchenko “Which Way Will Ukraine Swing?”

Formal adoption of non-alignment could gain Ukraine “geostrategic space” in which to gather its own house. While emulation has its limits, proffering a prosperous, independent country like twenty-first-century Sweden is a more appealing goal than vassal-state Finland during the Cold War.

Few carrots and no sticks

Whatever models are invoked or diplomatic terms applied, crafting a solution to the “Ukrainian question” will not be easy. For the United States, there are limited levers available. It should speak frankly to Ukraine about its true prospects for NATO membership. Continuing to emptily support this aspiration is detrimental to the Ukrainians considering more realistic options. Fundamentally, America should not move to put Ukraine in NATO; it’s past time it said so explicitly.

The United States could try to negotiate directly with Russia on the matter, perhaps offering a binding assurance NATO will formally forego Ukrainian membership in exchange for positive action by Russia on other aspects of Ukrainian security. Foremost in this regard should be a cessation of Russian military support to the Donbas separatists and the use of Moscow’s leverage to end that destructive conflict.

Other concessions from Russia will be more difficult to extract. Return of Crimea is almost certainly a non-starter. Annexation of the peninsula was arguably the defining moment of Putin’s reign; returning it would be a heavy blow to his personal prestige and Russia’s national pride. Russia has already made major investments in the peninsula’s civilian and military infrastructure.43For an overview of Russia’s investment in Crimea’s economy and civilian infrastructure, see Andrew Wilson and Ridvan Bari Urcosta, “Crimea: Russia’s Newest Potemkin Village,” European Council on Foreign Relations, April 30, 2019. https://www.ecfr.eu/article/commentary_crimea_russias_newest_potemkin_village. For details on its deployment of enhanced military capabilities since annexation, see Michael Petersen, “The Naval Power Shift in the Black Sea,” War on the Rocks, January 29, 2019. https://warontherocks.com/2019/01/the-naval-power-shift-in-the-black-sea/. Finally, there does not seem to be strong support among Crimeans themselves for returning to Ukraine.44See John O’Loughlin, Gerard Toal, and Kristen M. Bakke, “To Russia With Love,” Foreign Affairs 73, April 3, 2020. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/ukraine/2020-04-03/russia-love. Regardless of the lawless way it was attained, in all likelihood, Crimea is now Russia’s.

The truth, though, remains that the United States has a weak hand in terms of what it can and cannot do to help Ukraine. With no vital U.S. interests at stake, the imbalance of interest with Russia is unavoidable. America shouldn’t engage in policies that would recklessly endanger its own security by inviting direct conflict with Russia—there is therefore only so much it can do to responsibly aid Ukraine. As emphasized above, seeking stability and mitigating conflict is the U.S. priority.

Encouraging the EU to take more responsibility for Ukraine could be another diplomatic approach. It would be wrong to say that Moscow does not object to deeper integration by Ukraine into Western economic structures. After all, the 2014 crisis was sparked in large measure by Yanukovych’s abrogation of Ukraine’s EU association agreement in deference to Moscow’s wishes. That said, closer ties to the EU might be the most Russia is willing to accept—in the end, it has had to learn to live with a revival of the much-despised EU association agreement. Internally, increased integration with the EU could be the minimum necessary to assuage those Ukrainians who desire a genuine European identity.

And, clearly, closer ties to the EU are not nearly as provocative for Moscow as NATO membership. A formal stance of non-alignment by Ukraine could additionally defuse any concerns on this score. It would serve to clarify Ukraine’s western-oriented policies were formally rooted in economic concerns, not hard security interests. Neutrality for Ukraine would also not rule out the prospect of it someday joining the European Union in full; multiple current EU members practice some form of non-alignment, including the countries discussed above as potential models for Ukraine.45Prospects for actual membership in the European Union for Ukraine remain uncertain, though. Absorbing Ukraine would be a huge (and costly) undertaking for the EU. Already some EU member states have expressed reservation over the issue, in part because of concerns over potential Russian backlash, but also due to Ukraine’s sluggish implementation of its obligations under the association agreement. To cite one example, in the Netherlands, voters overwhelmingly rejected the association agreement with Ukraine in a non-binding referendum, prompting the Dutch government to request an explanatory text be added to the agreement clarifying that the association agreement did not guarantee Ukraine eventual EU membership nor entail any form of military assistance. The Dutch Senate eventually ratified the agreement. See Peter Teffer, “Netherlands Ratifies EU-Ukraine Treaty,” Euobserver, May 30, 2017, https://euobserver.com/foreign/138060. On concerns over the slow-pace of implementation of Ukraine’s obligations under the association agreement, see Balazs Jarabik, Gwendolyn Sasse, Natalia Shapalova, and Thomas De Waal, “The EU and Ukraine: Taking a Breath,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, February 27, 2018, https://carnegieendowment.org/2018/02/27/eu-and-ukraine-taking-breath-pub-75648.

An essential starting point for crafting any Ukrainian policy of neutrality, though, begins with it abandoning false fantasies of salvation through NATO. For the United States to be a genuine friend to Kyiv, greater honesty on that issue would be of service.

Endnotes

- 1Robyn Dixon and Natalie Gryvnyak, “Ukraine’s Zelensky Wants to End a War in the East. His Problem: No One Agrees How to Do It,” The Washington Post, March 19, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/ukraines-zelensky-wants-to-end-a-war-in-the-east-his-problem-no-one-agrees-how-to-do-it/2020/03/19/ae653cbc-6399-11ea-8a8e-5c5336b32760_story.html.

- 2John Lloyd, “In Ukraine, a Choice of Civilizations,” Reuters, October 17, 2013. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-lloyd-ukraine/column-in-ukraine-a-choice-of-civilizations-idUSBRE99G0RE20131017.

- 3Gerard Toal, Near Abroad, New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2017, 211–212, 288.

- 4Gerard Toal, John O’Loughlin, and Kristen M. Bakke, “Is Ukraine Caught between Europe and Russia? We Asked Ukrainians This Important Question,” The Washington Post, February 26, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/02/26/is-ukraine-caught-between-europe-russia-we-asked-ukrainians-this-important-question/.

- 5Barry R. Posen, “Ukraine: Part of America’s ‘Vital Interests’?” The National Interest, May 12, 2014. https://nationalinterest.org/feature/ukraine-part-americas-vital-interests-10443.

- 6For a thorough discussion on Ukraine’s path to independence and Rukh’s role, see Bohdan Nahaylo, The Ukrainian Resurgence, Toronto and Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1999. For an excellent account of the Baltic independence movements see Anatol Lieven, The Baltic Revolution: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and the Path to Independence, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1993.

- 7Steven Pifer, The Trilateral Process: The United States, Ukraine, Russia and Nuclear Weapons, Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, May 2011, 4.

- 8For full text, see “Annex I: Memorandum on Security Assurances in Connection with Ukraine’s Accession to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons,” contained in “Letter dated 7 December 1994 from the Permanent Representatives of the Russian Federation, Ukraine, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the United States of America to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General,” http://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/s_1994_1399.pdf.

- 9See Cody M. Poplin and Benjamin Bissell, “Throwback Thursday: The 1994 Budapest Memorandum,” Lawfare, November 20, 2014, https://www.lawfareblog.com/throwback-thursday-1994-budapest-memorandum, and Ron Synovitz, “Explainer: The Budapest Memorandum and Its Relevance to Crimea,” Radio Free Europe, February 28, 2014, https://www.rferl.org/a/ukraine-explainer-budapest-memorandum/25280502.html.

- 10The Freedom Agenda was the name given to the Bush administration’s post-9/11 strategic vision, which linked American security with the promotion of liberty abroad. Bush’s second inaugural address is considered to be the clearest enunciation of this approach to world affairs. For a transcript, see National Public Radio, “President Bush’s Second Inaugural Address,” January 20, 2005. https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=4460172.

- 11Toal, Near Abroad, 94–95.

- 12Steven Erlanger and Steven Lee Myers, “NATO Allies Oppose Bush on Georgia and Ukraine,” The New York Times, April 3, 2008. https://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/03/world/europe/03nato.html.

- 13Section 23 of the Bucharest Summit Declaration states, “NATO welcomes Ukraine’s and Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic aspirations for membership in NATO. We agreed today that these countries will become members of NATO.” See North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “Bucharest Summit Declaration,” Issued by the Heads of State and Government participating in the meeting of the North Atlantic Council in Bucharest on 3 April 2008.https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/official_texts_8443.htm.

- 14See, for example, the comments by Canadian Foreign Minister John Baird in Simona Kralova, “Crimea Seen as ‘Hitler-style’ Land Grab,” BBC News, March 14, 2014, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-26488652; remarks by the German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble in “German Minister Compares Putin’s Ukraine Moves to Hitler in 1938,” Reuters, March 31, 2014, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-ukraine-russia-germany/german-minister-compares-putins-ukraine-moves-to-hitler-in-1938-idUSBREA2U0S420140331; the editorial by Estonian President Toomas Hendrik Ilves, “The United States and Europe Need a New Rulebook for Russia,” Washington Post, March 27, 2014, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/toomas-hendrik-ilves-the-united-states-and-europe-need-a-new-rulebook-for-russia/2014/03/27/e15dad62-b5bb-11e3-8020-b2d790b3c9e1_story.html; and the op-ed by former Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvilli, “The West Must Not Appease Putin,” Washington Post, March 6, 2014, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/mikheil-saakashvili-the-west-must-not-appease-putin/2014/03/06/db9e0c82-a4a9-11e3-8466-d34c451760b9_story.html.

- 15Timothy Morrison, former Senior Director for Europe and Russia, National Security Council, as quoted in House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, The Trump-Ukraine Impeachment Inquiry Report, December 2019, 18. https://intelligence.house.gov/uploadedfiles/the_trump-ukraine_impeachment_inquiry_report.pdf.

- 16“Secretary Michael R. Pompeo and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy at a Press Availability,” U.S. Embassy in Ukraine, January 31, 2020. https://ua.usembassy.gov/secretary-michael-r-pompeo-and-ukrainian-president-volodymyr-zelenskyy/.

- 17“Press Conference by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg Following the Meeting of NATO Ministers of Foreign Affairs,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, April 2, 2020. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/opinions_174772.htm.

- 18Toal, O’Loughlin, and Bakke, “Is Ukraine Caught between Europe and Russia?”

- 19See the chart, “Support for Military Relations in Ukraine by macro region,” from Toal, O’Loughlin, and Bakke’s research. The figure has not been officially published but was shared on Twitter by Toal as part of a thread explicating the information contained in “Is Ukraine Caught between Europe and Russia?” Gerard Toal, Twitter post, February 26, 2020, 9:54 a.m. https://twitter.com/Toal_CritGeo/status/1232680229480562688/photo/1.

- 20In 1993, for example, the CIA produced an analysis predicting Ukraine’s eventual cleavage along east-west lines. See Daniel Williams and R. Jeffrey Smith. “U.S. Intelligence Sees Economic Plight Leading to the Breakup of Ukraine,” Washington Post, January 15, 1994. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1994/01/25/us-intelligence-sees-economic-plight-leading-to-breakup-of-ukraine/48282f8d-0fe9-457f-b252-39d98137c003/.

- 21Michael Kofman, “Russian Performance in the Russo-Georgian War Revisited,” War on the Rocks, September 4, 2018. https://warontherocks.com/2018/09/russian-performance-in-the-russo-georgian-war-revisited/.

- 22Nicholas V. Riasanovsky, A History of Russia, New York and Oxford; Oxford University Press, 1984, 23–60.

- 23Norman Davies, God’s Playground, Vol. 2: 1795 to the Present, New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1982.

- 24For an overview of Ukrainian neutrality since its independence and alternative European models, see the draft research paper by Viktoria Potapkina, “Ukrainian Neutrality: Myth or Reality?” November 30, 2010, available via E-International Relations Students: https://www.e-ir.info/2010/11/30/ukraine%e2%80%99s-neutrality-a-myth-or-reality/

- 25Zbigniew Brzezinski, “Russia Needs a ‘Finland Option’ for Ukraine,” Financial Times, February 23, 2014. https://www.ft.com/content/7f722496-9c86-11e3-b535-00144feab7de, and Henry Kissinger, “To Settle the Ukraine Crisis Start at the End,” The Washington Post, March 5, 2014. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/henry-kissinger-to-settle-the-ukraine-crisis-start-at-the-end/2014/03/05/46dad868-a496-11e3-8466-d34c451760b9_story.html.

- 26Charles M. Perry, Michael J. Sweeney, and Andrew C. Winner, Strategic Dynamics in the Nordic-Baltic Region: Implications for U.S. Policy. Dulles, VA: Brassey’s, 2000, 123.

- 27Arne Olav Brundtland, “Nordic Security at the End of the Cold War: Old Legacies and New Challenges,” in Nordic-Baltic Security: An International Perspective, eds. Arne Olav Brundtland and Don M. Snider, Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 1994, 9.

- 28“Domestic Developments and Foreign Politics, 1948-66,” in Finland: A Country Study, eds. Eric Solsten and Sandra W. Meditz, Washington, DC: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1988. http://countrystudies.us/finland/25.htm.

- 29Ed Dutton, “Playing the Blame Game: Finland & the Soviets,” History Today 58, no. 10, October 2009. https://www.historytoday.com/archive/playing-blame-game-finland-soviets.

- 30See Franz-Stefan Gady, “Austrian Neutrality: A Model for Ukraine,” The National Interest, March 6, 2014. https://nationalinterest.org/commentary/austrian-neutrality-model-ukraine-10005?page=0%2C1, and Douglas Macgregor, “The Ukrainian State Treaty: An Offer Putin Can’t Refuse,” Foreign Policy, August 1, 2016. https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/08/01/the-ukrainian-state-treaty-an-offer-putin-cant-refuse-russia-nato-ukraine/.

- 31Gady, “Austrian Neutrality: A Model for Ukraine.”

- 32“The 1955 State Treaty and Austrian Neutrality,” in Austria: A Country Study, ed. Eric Solsten, Washington, DC: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1994. http://countrystudies.us/austria/47.htm.

- 33Gunter Bischof, “Eisenhower and the Austrian Treaty,” in Eisenhower: A Centenary Assessment, eds. Gunter Bischof and Stephen E. Ambrose, Baton Rouge and London: LSU Press, 1995, 148–149.

- 34“Ukraine Votes to Abandon Neutrality, Set Sights On NATO,” Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty, December 23, 2014. https://www.rferl.org/a/ukraine-parliament-abandons-neutrality/26758725.html.

- 35Toal, O’Loughlin, and Bakke, “Is Ukraine Caught between Europe and Russia?”

- 36Following his recent appointment, Defense Minister Andriy Taran suggested Ukraine attaining military compatibility with NATO—likely a prerequisite for entry into the alliance—was not truly realistic, calling the goal “ambitious but unachievable.” While his comments didn’t explicitly rule out Ukraine joining NATO, it acknowledged some of the concrete challenges that process would entail. It predictably provoked a harsh response from alliance advocates within Ukrainian policy circles—and a subsequent retraction. See Tetiana Gaiduk, “Does Zelensky’s Ukraine Still Want to Join NATO?” The Atlantic Council, April 13, 2020, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/does-zelenskyys-ukraine-still-want-to-join-nato/, and Ilya Timtchenko, “Which Way Will Ukraine Swing?” Foreign Policy, May 20, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/05/20/ukraine-zelensky-corruption-russia-european-union/.

- 37For a more fulsome discussion of the history of Swedish neutrality and non-alignment, see John Logue, “The Legacy of Swedish Neutrality,” in The Committed Neutral: Swedish Foreign Policy, ed. Bengt Sundelius, London and New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 1989. Kindle Edition.

- 38See, for example, Kristian Nielsen and Heiko Paabo, “How Russian Soft Power Fails in Estonia: Or, Why the Russophone Minorities Remain Quiescent,” The Journal of Baltic Security 1, no. 2, 2015: 125–57. https://content.sciendo.com/view/journals/jobs/1/2/article-p125.xml.

- 39For a broader discussion, see Cynthia Buckley, Ralph Clem, and Erik Herron, “How to Stabilize Ukraine Long Term? Securitize Well-Being,” War on the Rocks, December 4, 2019. https://warontherocks.com/2019/12/how-to-stabilize-ukraine-long-term-securitize-well-being/.

- 40Anders Aslund, “Ukraine’s Underrated Economy Is Poised for a Strong 2020,” The Atlantic Council, January 6, 2020. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/ukraines-underrated-economy-is-poised-for-a-strong-2020/.

- 41Anders Aslund, “What Is Wrong with the Ukrainian Economy?” The Atlantic Council, April 26, 2019. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/what-is-wrong-with-the-ukrainian-economy/.

- 42Aslund, “What is Wrong with the Ukrainian Economy,” and Timtchenko “Which Way Will Ukraine Swing?”

- 43For an overview of Russia’s investment in Crimea’s economy and civilian infrastructure, see Andrew Wilson and Ridvan Bari Urcosta, “Crimea: Russia’s Newest Potemkin Village,” European Council on Foreign Relations, April 30, 2019. https://www.ecfr.eu/article/commentary_crimea_russias_newest_potemkin_village. For details on its deployment of enhanced military capabilities since annexation, see Michael Petersen, “The Naval Power Shift in the Black Sea,” War on the Rocks, January 29, 2019. https://warontherocks.com/2019/01/the-naval-power-shift-in-the-black-sea/.

- 44See John O’Loughlin, Gerard Toal, and Kristen M. Bakke, “To Russia With Love,” Foreign Affairs 73, April 3, 2020. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/ukraine/2020-04-03/russia-love.

- 45Prospects for actual membership in the European Union for Ukraine remain uncertain, though. Absorbing Ukraine would be a huge (and costly) undertaking for the EU. Already some EU member states have expressed reservation over the issue, in part because of concerns over potential Russian backlash, but also due to Ukraine’s sluggish implementation of its obligations under the association agreement. To cite one example, in the Netherlands, voters overwhelmingly rejected the association agreement with Ukraine in a non-binding referendum, prompting the Dutch government to request an explanatory text be added to the agreement clarifying that the association agreement did not guarantee Ukraine eventual EU membership nor entail any form of military assistance. The Dutch Senate eventually ratified the agreement. See Peter Teffer, “Netherlands Ratifies EU-Ukraine Treaty,” Euobserver, May 30, 2017, https://euobserver.com/foreign/138060. On concerns over the slow-pace of implementation of Ukraine’s obligations under the association agreement, see Balazs Jarabik, Gwendolyn Sasse, Natalia Shapalova, and Thomas De Waal, “The EU and Ukraine: Taking a Breath,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, February 27, 2018, https://carnegieendowment.org/2018/02/27/eu-and-ukraine-taking-breath-pub-75648.

More on Eurasia

Featuring Lyle Goldstein

January 19, 2026

January 13, 2026

January 8, 2026

Events on NATO