November 23, 2022

Reconfiguring NATO: The case for burden shifting

By Rajan Menon

Key points

- NATO should be reconfigured to shift the primary responsibility for defending Europe to Europeans. This far-reaching change is appropriate given Europe’s transformed security environment.

- Reducing or ending the American military presence in Europe should not depend on whether European governments implement burden shifting; indeed U.S. force reductions are a prerequisite for burden shifting.

- Europe has the economic and technological resources needed to assume the principal responsibility for its own defense.

- Burden shifting is not merely about increased European defense spending; it also requires better military coordination among European states.

- Russia’s attack on Ukraine has revealed the weaknesses of the Russian military, which makes burden shifting even more appropriate.

This explainer begins by recounting how an American-led NATO, a key element in U.S. global primacy, lived on despite the collapse of the Soviet Union, the threat it was meant to deter—and, if necessary, defeat. The next section highlights the implicit bargain that has sustained NATO: U.S. preponderance in Europe, achieved by the American willingness to serve as the continent’s indispensable protector, in exchange for Europeans’ freedom to spend more on butter and less on guns. Next comes a set of proposals to move NATO from burden sharing, a perennial point of contention within the pact, to a more far-reaching change, burden shifting, an idea that the Russian invasion of Ukraine has made even more feasible and prudent. The explainer concludes by assaying the prospects for burden shifting and challenging prominent counterarguments.

Cold War NATO reflected core U.S. interests

When NATO was created in 1949, Western Europe, shattered or enfeebled by the war, lacked the wherewithal to defend itself. Although the USSR had suffered grievously during the war, the Red Army was Europe’s largest military force after 1945; its presence extended into the heart of Germany, via the communist German Democratic Republic. By ensuring Western Europe’s protection, the United States, through NATO, also provided the security European countries needed for economic reconstruction and democratic consolidation. It did so by maintaining, permanently, a substantial military presence in Europe, even though the number of soldiers declined from a Cold War peak of 400,633 in 1957 to 200,000 in 1989.1“Number of United States Military Personnel in Europe from 1950 to 2021,” Statista, https://www.statista.com/statistics/1294309/us-troops-europe/.

NATO may have been resented in some European quarters, notably in France under Charles de Gaulle, as a symbol of the continent’s dependence on an overbearing United States, but the alliance enjoyed solid public support in its member countries. Its success also owed to its clear mission: deterring and, failing that, defeating a Soviet attack on Western Europe, thereby preventing the emergence of a Eurasian hegemon, a goal that became central to American grand strategy.

A more complete and catchier version was offered by the alliance’s first Secretary-General, Lord Ismay, who quipped that its purpose was to “keep the Russians out, the Germans down, and the Americans in.” It did all three things surpassingly well.

NATO’s expansion: Eastward and outward

The rationale for the U.S. presence in Europe changed during the Cold War. What had begun as a temporary measure aimed at shoring up the balance of power by containing the Soviet Union turned into a long-term policy of defending Europe. That, in turn, ensured Europe’s dependence on American protection—even after the Cold War ended. Thus the 1992 Defense Planning Guidance (in its original form before its leak engendered controversy and a rewrite) maintained that a strong U.S. military presence in Europe, and other regions, served not only to deter rivals’ aggression, but also to limit the strength and independence of allies.2“‘Prevent the Reemergence of a New Rival’: The Making of the Cheney Regional Defense Strategy, 1991–1992,” National Security Archive, February 26, 2008, https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nukevault/ebb245/.

Once the Soviet Union imploded in 1991, NATO’s reason for being was no longer obvious; some even questioned its reason for being.3Rajan Menon, The End of Alliances (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007). For one thing, there was no longer any need for the U.S. military to “keep the Russians out.” The USSR’s successor state, the Russian Federation, was debilitated by an economic crisis (GDP fell by an estimated 40 percent between 1991 and 1998), political upheaval, and civil war during the 1990s in Chechnya.4Sergei Guriev, “Russia’s Constrained Economy: How the Kremlin Can Spur Growth,” Foreign Affairs 95, no. 3 (May/June 2016): 18–22, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43946853. Consequently, no reasonable person in Europe or the United States worried about an attack by the Russian army. If it posed a threat at all, it was not to Europe but to Russia’s own embryonic democracy. Furthermore, by the late 1980s, the fear of a revanchist, remilitarized Germany had long faded; the country had become a thriving democracy, had atoned for its past misdeeds, and was not in the least enthusiastic about wielding military power, to say nothing of militarism.

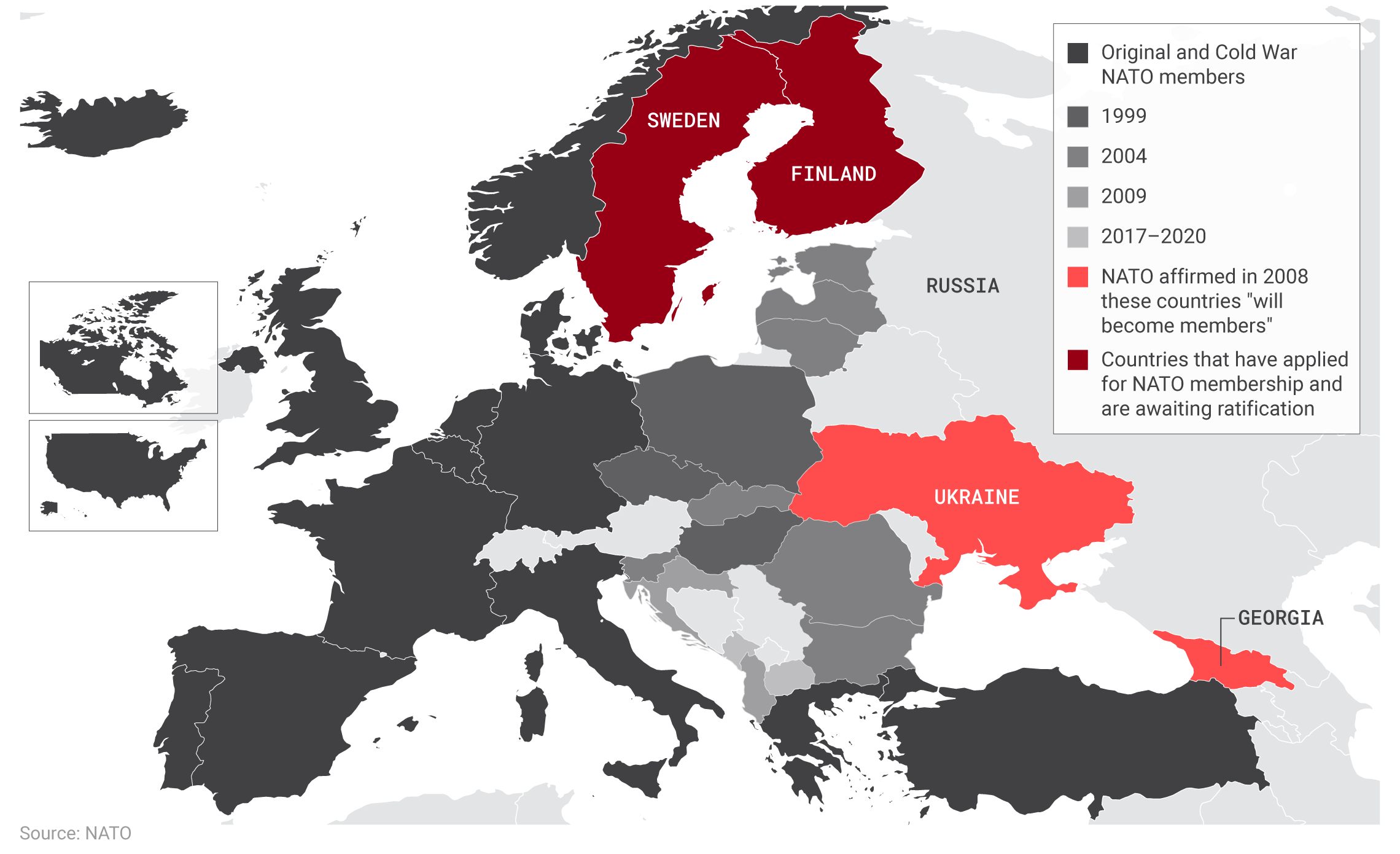

But American leaders saw it, even after the end of the Cold War, preserving U.S. influence in Europe required that NATO continue to be relevant. Hence, starting with President Bill Clinton, they refashioned the alliance by expanding it in two ways: eastward and outward. Although the number of American military personnel stationed in Europe had declined to 62,338 by 2021, starting in March 1999 the alliance began expanding eastward. Inducted into NATO’s ranks were countries that had until recently been Soviet allies or part of the Soviet Union, but eventually others as well. With North Macedonia’s entry in March 2020, the alliance’s membership reached 30, compared to the Cold War peak of 16. The shock created by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, set the stage for a further increase in membership by prompting Sweden and Finland to submit applications for entry. Once they formally join, NATO’s size will have doubled from its Cold War peak, and Finland’s membership will increase the length of the NATO-Russia border twofold.5Henry Foy, “NATO’s Eastern Front: Will the Military Buildup Make Europe Safer?” Financial Times, May 4, 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/a1a242c3-9000-454d-bec7-c49077b2cc6c?shareType=nongift.

Among the arguments offered in support of NATO expansion was that membership in the alliance would help the former communist countries who were admitted into the alliance move toward democracy and capitalism so that their state-run command economies and one-party polities would give way to private property, markets, and elected governments. Why membership in a military alliance was required to usher in these changes when the EU seemed much better suited to fostering them was scarcely self-evident.

One consequence of NATO’s eastward expansion has been that it reduced the prospects for European defense autonomy—the ability of European states to act in concert to defend the continent on their own. The countries on the expanded alliance’s eastern front, particularly Poland and the three Baltic states, adamantly oppose autonomy—a concept France has advocated intermittently—for fear that it will reduce, even eliminate the American military presence. The want is an even larger number of American soldiers on European soil and have a reliable and influential supporter in Britain, which remains Washington’s closest ally in NATO.

NATO expansion since its founding

The history of NATO expansion raises the question of whether there was an alternative way of organizing Europe’s defense after the Cold War.

NATO also expanded outward by assuming responsibilities beyond pure defense of its existing members’ borders; in effect taking to heart former Republican Senator Richard Lugar’s observation that after the Cold War that NATO would go “out of area or out of business,” and that too ensured that security link between Europe and the United States would remain intact, and even be strengthened.6Richard Lugar, “NATO: Out of Area or Out of Business; A Call for U.S. Leadership to Revive and Redefine the Alliance,” Richard G. Lugar Senatorial Papers, accessed October 5, 2022, https://collections.libraries.indiana.edu/lugar/items/show/342. In this way, NATO was a solution in search of a problem. Among the consequences of this second expansion were the alliance’s interventions in Bosnia (1995), Kosovo (1999), Afghanistan (2001), and Libya (2011).

These out-of-area missions also illustrated the continuing lopsidedness of NATO’s military capabilities. Although multilateral in form, these were U.S.-led operations in which its European allies played a supporting role. Europe certainly could not have undertaken these operations without the United States. The vast majority of the strike sorties in Kosovo were carried out by American aircraft, although non-U.S. members have contributed substantially to the post-war stabilization force, KFOR.7“Kosovo Force,” Military Fandom, https://military-history.fandom.com/wiki/Kosovo_Force#Contributing_states.

In Libya, Washington did hand the reins to its allies after the initial phase of airstrikes against Libyan air defenses, but they soon faced shortages of munitions and airpower, and fully half of the airstrikes were conducted by two NATO members, Britain and France.8“NATO Runs Short of Munitions in Libya: report,” Space War, April 15, 2011, https://www.spacewar.com/reports/NATO_runs_short_of_munitions_in_Libya_report_999.html. Europe’s weaknesses in power projection ensure that the alliance’s out-of-area operations will hinge on the United States.

As with NATO’s eastward expansion, its outward expansion perpetuated Europe military dependence on the U.S. The bargain underlying NATO from its outset thus remained in place: defending Europe contributed to American primacy. Europe for its part gained security on the cheap. But while this deal made sense under realist logic during the Cold War, it has become questionable in its aftermath because Europe can defend itself and out-of-area-operations, for all their multilateral veneer, are effectively American undertakings, with some, notably the 2011 campaign in Libya, having left still-continuing violence and upheaval in its wake.9Frederic Wehrey, Burning Shores: Inside the Battle for the New Libya (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2018); Vivian Yee and Mohammed Abdusamee, “After a Decade of Chaos, Can a Splintered Libya Be Made Whole?” New York Times, February 16, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/16/world/middleeast/libya-government-qaddafi.html.

Burden sharing: A dead end

The lopsided distribution of power within NATO has allowed European to benefit from American protection and keep their own defense spending substantially lower relative to the U.S. as a percentage of GDP.10“Defense Spending as a % of Gross Domestic Product (GDP),” U.S. Department of Defense, https://www.defense.gov/Multimedia/Photos/igphoto/2002099941/. That, in turn, has made it easier for them to fund their generous social welfare programs. Not all NATO allies have been minimalists in defense spending, but many have been and continue to be even though they could easily afford to spend more.

West Germany is a prime example. It recovered from the Second World War and soon became the richest European country in NATO; yet from 1963 to 1989, it consistently spent half what the United States did as a percentage of GDP, something that would not have been possible absent the American defense guarantee personified by the over 200,000 soldiers Washington deployed in West Germany.11“Germany Military Spending/Defense Budget 1960–2022,” Macrotrends, https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/DEU/germany/military-spending-defense-budget; Michael A. Allen, Michael E. Flynn, and Carla Martinez Machain, “U.S. Global Military Deployments, 1950–2020,” Conflict Management and Peace Science 39, no. 3 (May 2022): 351–370, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/07388942211030885.

This pattern has not changed despite the end of the Cold War. Between 2005 and 2020, for example, German defense spending as a proportion of GDP ranged from 1.1 percent to 1.4 percent.12“Military expenditure (% of GDP)—Germany,” World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.GD.ZS?locations=DE. During that same period U.S. defense spending ranged from a high of 4.8 percent and a low of 3.3 percent.13“Military expenditure (% of GDP)—United States,” World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.GD.ZS?locations=US. And this despite the Bundeswehr chronic storages in personnel, armaments, spare parts, and basic supplies, all of which reduced its military readiness and capabilities.14Rajan Menon, “The Sorry State of Germany’s Armed Forces,” Foreign Policy, June 18, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/06/18/trump-withdraw-troops-germany-military-spending/.

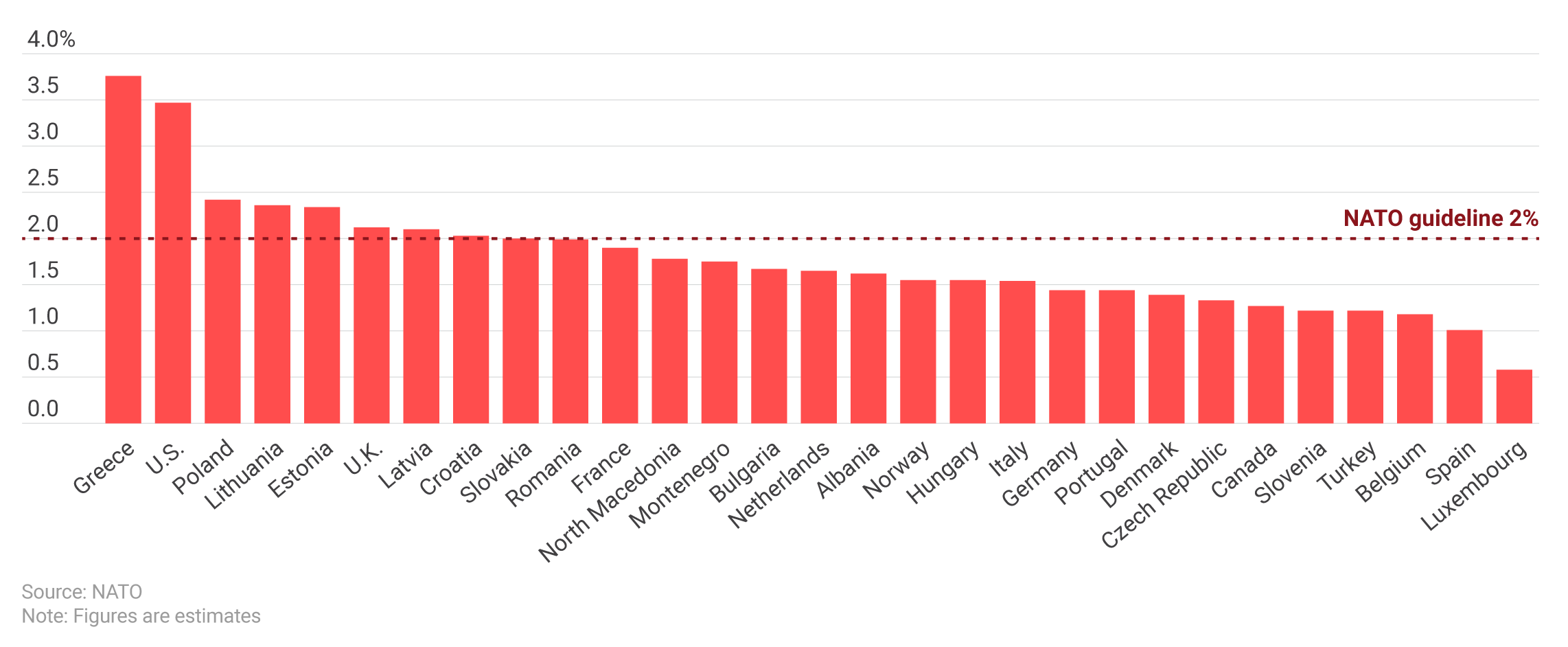

Germany may be the most telling example of inequitable burden sharing given the gap between what it can afford to contribute to the common defense and what it does, but within NATO the problem is more general. Take the guidelines the alliance adopted at its 2014 Wales summit to get each NATO member to spend at least 2 percent of GDP on defense and a minimum of 20 percent of military spending on weapons procurement. The alliance’s data show that as of January 2022, 21 out of the alliance’s 30 members (70 percent) failed to reach the former benchmark, and only seven, or one-third, excluding the United States, had met both.15The record was better on the proportion of defense spending devoted to equipment: Only eight members fell below the 20 percent threshold. “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2021),” NATO, March 31, 2022, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2022/3/pdf/220331-def-exp-2021-en.pdf.

Despite Washington’s longstanding efforts to goad its European allies into spending more for their own defense, it has never created a crisis, let alone issue an ultimatum, over burden sharing.16For decades, U.S. leaders have called on European allies to increase defense spending but did little to create the conditions impelling Europe to do so. See Benjamin H. Friedman and Joshua Shifrinson, “Trump, NATO, And Establishment Hysteria,” War on the Rocks, June 16, 2017, https://warontherocks.com/2017/06/trump-nato-and-establishment-hysteria/; U.S. General Accounting Office, ”U.S.-NATO Burden Sharing Allies’ Contributions to Common Defense During the 1980’s,” October 1990, https://www.gao.gov/assets/nsiad-91-32.pdf; James S. Robbins, “Trump’s NATO Heresy Was Eisenhower’s Wisdom: James Robbins,” USA Today, October 3, 2016, https://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2016/10/03/trumps-nato-heresy-eisenhowers-wisdom-james-robbins-column/91282406/; “Rumsfeld Urges Allies to Boost Defense Spending,” NBC News, February 4, 2006, https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna11170234#.WTHsPGjys2w; Ted Galen Carpenter, “NATO, European Spending and US Grievances,” Cato Institute, May 12, 2015, https://www.cato.org/commentary/nato-european-spending-us-grievances. As one scholar has aptly put it, “the United States would only test the bonds of transatlantic unity so far in order to extract greater defense commitments from the allies.”17Colby Lutz, “Burden Sharing Dilemmas and NATO’s Tumultuous Summer,” War Room—U.S. Army War College, September 27, 2018, https://warroom.armywarcollege.edu/articles/natos-tumultuous-summer/. Nor, because of its determination to maintain its preponderant position in Europe, has the United States favored European defense autonomy after the Cold War.

NATO 2022 defense spending as a percentage of GDP

NATO-Europe’s defense spending has increased since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but they should spend even more and take up the burden of Europe’s defense from the United States.

Washington has favored greater European defense spending, but only within NATO’s confines and never in a way that would end Europe’s dependence on the United States or erode unrivaled American influence in Europe. It has supported European collaboration in defense production, provided American armament producers were not put at a disadvantage in Europe’s arms market.

Moving toward burden shifting

The time has long since come to end the perennial discussions over burden sharing and to move toward burden shifting. Burden shifting goes beyond defense spending levels. It involves the concrete military capabilities that Europe needs to assume the primary responsibility for its defense: for example, rapid deployment, readiness, aerial refueling, strategic airlift capabilities, and what is known as C4ISR (Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance).18Hans Binnendijk, Daniel S. Hamilton, and Alexander Vershbow, “Strategic Responsibility: Rebalancing European and Trans-Atlantic Defense,” Brookings Institution, June 24, 2022, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/strategic-responsibility-rebalancing-european-and-trans-atlantic-defense/. As Guy Verhofstadt, a former prime minister of Belgium, put it in 2021, “Weakness has become a European habit…”19Guy Verhofstadt, “Europe’s Military Weakness is Indefensible!” Euobserver, October 6, 2021, https://euobserver.com/opinion/153129. Given Europe’s wealth and the potential for mobilizing EU-wide resources, this is a problem that can be overcome, perhaps through the creation of a truly effective EU defense force within NATO, something Verhofstadt favors. Spending more is not a cure-all and ought to be only one part of the effort: there are many ways to increase defense budgets without improving combat power.

There are, at minimum, four steps Europeans should take as part of burden shifting:

1. Change the spending pattern

Given how much larger Europe’s economy is than Russia’s, if NATO’s European members were each to devote 3 percent of GDP to defense (that is, less than the 3.47 percent the U.S. is expected to allocate in 2022) rather than the anticipated average 1.74 percent, Russia would have to shoulder a staggering defense burden to keep up.20“Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2022),” NATO, June 27, 2022, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2022/6/pdf/220627-def-exp-2022-en.pdf. Even now, NATO’s European members combined spend more than 3.5 times more on defense ($260 billion in 2021) than Russia ($65 billion) does.21“Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2021),” NATO, March 31, 2022, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2022/3/pdf/220331-def-exp-2021-en.pdf; Brendan Cole, “Russia Increases Defense Spending by 20% as it Struggles to Replace Weapons,” Newsweek, June 14, 2022, https://www.newsweek.com/ukraine-russia-weapons-defense-sanctions-1715568. But they don’t spend the money well.

Europe should either increase spending and earmark the additional sums for the acquisition of major armaments or allocate more existing expenditures toward the long-term acquisition of major armaments and war-related technologies, such as C4ISR—capabilities for which it relies heavily on the United States.

2. Increase coordination in armament production

NATO-Europe should adopt a long-term plan to increase cooperation in weapons production to eventually end, or at least reduce substantially, duplication in arms production.22Valerio Briani, “Armaments Duplication in Europe: A Quantitative Assessment,” Centre for European Policy Studies, July 16, 2013, https://www.ceps.eu/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/PB%20297%20Briani%20Duplication%20in%20EU%20armed%20forces%20-.pdf. Increasing cross-border joint ventures, ideally through an agreed-upon division of labor based on comparative advantage, ought to be part of this effort. Although the EU has made some moves in this direction after its Common Defense and Security Policy (2009) and follow-on initiatives, such as the European Defense Fund (2021), were adopted, European arms manufacturing and acquisition remain overwhelming national. That has been enabled by Article 346 of the EU Treaty that allows carveouts to the single market principle intended to protect national defense production and procurement.23Raluca Csernatoni, “The EU’s Defense Ambitions: Understanding the Emergence of a European Defense Technological and Industrial Complex,” Carnegie Europe, December 6, 2021, https://carnegieeurope.eu/2021/12/06/eu-s-defense-ambitions-understanding-emergence-of-european-defense-technological-and-industrial-complex-pub-85884; “Common Security and Defence Policy,” European Parliament, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/factsheets/en/sheet/159/common-security-and-defence-policy; Alexandra Brzozowski, “European Parliament Backs EU’s €7.9 billion Defence Fund,” Euractiv, April 30, 2021, https://www.euractiv.com/section/defence-and-security/news/european-parliament-backs-eus-e7-9-billion-defence-fund/; Gustav Gressel and Nick Witney, “Out of the Dark: Reinventing European Defence Cooperation,” European Council on Foreign Relations, March 18, 2022, https://ecfr.eu/article/out-of-the-dark-reinventing-european-defence-cooperation/. Voluntary cross-border cooperation can skirt the daunting challenge of amending the treaty.

3. A solely European Rapid Response Force

NATO plans to expand its Rapid Response Force (RF) from 40,00 to 300,000, although details about the new force are not yet available.24Michael Birnbaum and Emily Rauhala, “Those 300,000 High-Readiness NATO Troops? ‘Concept,’ Not Reality,” Washington Post, June 29, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/06/29/those-300000-high-readiness-nato-troops-concept-not-reality/. Still, if a force of this size does emerge, it should consist entirely of European and British troops. A European general should command the RF if it deploys, and that post should rotate in intervals among different countries. NATO’s European members should decide which arms and defense technologies this force needs and commit to a schedule to ensure that it will have them.

4. An all-European defense of the eastern front

Soldiers deployed permanently on the alliance’s eastern front should be provided by NATO’s European members, including Britain. NATO should focus solely on the continent’s defense and not “out-of-area” operations. Europe’s security should be the alliance’s priority.

Burden shifting bypasses the nitty gritty of which NATO country spends, what it costs the United States to defend Europe, and whether any redistribution is needed in the interest of fairness.25The issue of NATO defense spending, what it would cost to defend Europe, and the value of redistribution of defense spending for fairness has been addressed by IISS and Barry Posen, among others. See Lucie Béraud-Sudreau and Nick Childs, “The U.S. and Its NATO Allies: Costs and Value,” International Institute of Strategic Studies, July 9, 2018, https://www.iiss.org/blogs/military-balance/2018/07/us-and-nato-allies-costs-and-value; Barry R. Posen, “A New Transatlantic Division of Labor Could Save Billions Every Year!” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, September 7, 2021, https://thebulletin.org/premium/2021-09/a-new-transatlantic-division-of-labor-could-save-billions-every-year/. Instead, burden shifting rests on the assumption that U.S. interests in Europe are best served by winding down its military presence there. Europeans can and ought to assume the responsibility for defending their continent. Even if Europe decides it does not want to assume this responsibility, U.S. interests in Europe would still be best served relinquishing the responsibility to defend Europe.

During the Cold War, with Europe still in recovery and the Warsaw Pact encompassing all of Eastern Europe, including half of Germany, the outsized American commitment made strategic sense. But it no longer does given the lack of a credible threat to U.S. interests in Europe. Europe has the resources needed to defend itself—if it is willing to make political decision to do so. But it will not take that step so long as the codependency that has marked the trans-Atlantic alliance continues and American and European leaders continue to perpetuate it.

Yes, the United States has a self-interest in a secure Europe, but Europeans’ self-interest in their continent’s security is far greater. Hence, they ought to be far more responsible for ensuing it than the United States, whose east coast lies nearly 4,000 miles away from Europe’s western shores. And they should match that concern with greater effort—especially now that they possess all the material means needed to do so, do not face any threat remotely comparable to the Soviet Red Army, have far more economic resources than Russia does, and are also much more technologically advanced.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine strengthens the case for burden shifting

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, NATO made four decisions that will boost its military strength. The first is to increase the number of American troops in Europe from 80,000 (before February 24, 2022) to 100,000 and to keep them there for the long haul.26Darlene Superville and Zeke Miller, “U.S. Boosting Military Presence in Europe Amid Russia Threat,” ABC News, June 29, 2022, https://abcnews.go.com/International/wireStory/biden-us-boosting-force-posture-europe-russia-threat-85913564. The second: to set aside the 1997 NATO-Russia Founding Act and permanently station troops on the alliance’s eastern front.27“Founding Act,” NATO, October 12, 2009, https://www.nato.int/cps/su/natohq/official_texts_25468.htm. Third: to expand the NATO Response Force from 40,000 to 300,000.28“NATO Response Force,” NATO, July 11, 2016, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/topics_49755.htm; Emily Rauhala and Annabelle Timsit, “NATO to Boost High-readiness Forces in ‘Biggest Overhaul’ Since Cold War,” Washington Post, June 27, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/06/27/nato-rapid-reaction-force-expansion/. Finally, pending unanimous approval from its members, NATO welcomed the membership applications of Finland and Sweden, strengthening NATO-Europe’s collective capacity.

Russia’s attack on Ukraine strengthens the case for reconfiguring NATO and burden shifting along the lines suggested here. Despite the Russian leadership’s much-vaunted drive to reform and modernize its armed forces after the problems revealed during the 2008 war with Georgia, Russian forces continue to struggle against Ukraine, a country far weaker in any of the standard measures of military power—GDP, military spending, and numbers of troops and major armaments.29Anton Lavrov, “Russian Military Reforms from Georgia to Syria,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, November 5, 2018, https://www.csis.org/analysis/russian-military-reforms-georgia-syria; Michael Kofman, “Russian Performance in the Russo-Georgian War Revisited,” War on the Rocks, September 4, 2018, https://warontherocks.com/2018/09/russian-performance-in-the-russo-georgian-war-revisited/. In fact, Russia is on its heels after stunning Ukrainian counteroffensives that have threatened its ability to hold the territory it has taken following its unjustified invasion.

The CIA estimated in the summer of 2022 that Russian military deaths in Ukraine totaled 15,000 and total casualties totaled 45,000.30Phil Stewart, “CIA Director Estimates 15,000 Russians Killed in Ukraine War,” Reuters, July 20, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/cia-director-says-some-15000-russians-killed-ukraine-war-2022-07-20/. In other words, at the war’s six-month mark, more of Russian soldiers were killed and wounded than during the Red Army’s decade-long fight against the Afghan mujahadeen. Ukrainian forces destroyed large numbers of Russian military equipment: tanks (an estimated 2,000), armored personnel carriers, artillery batteries, aircraft, and helicopters.31Isabel Van Brugen, “Russia Has Lost Over 2,000 Tanks Since War Began—Ukraine,” Newsweek, September 2, 2022, https://www.newsweek.com/russia-tanks-destroyed-war-ukraine-1739258. Russia’s military logistics network has repeatedly failed to deliver to the front the basics that Russian soldiers required to sustain themselves and to keep their weapons and vehicles in working order.

What Putin’s invasion of Ukraine demonstrates is that Russia poses little threat to Western Europe—the balance of power, which is what is most important for U.S. security and prosperity interests, heavily favors our European partners and allies. This reality offers the U.S. an opportunity to push its allies in Europe to take on a much greater responsibility for defending the continent without jeopardizing the overriding American interest in a stable Europe.

Yet leaders in the United States and its NATO allies have inexplicably concluded that the Russian threat extends beyond Ukraine to all of Europe and that that requires a bigger American military presence on the continent. Moreover, the head of the European Command, General Tod Walters, told the Senate Armed Service Committee in March that further increases may well be required.32“More U.S. Troops May Be Needed, Top General Predicts,” Politico, March 29, 2022, https://www.politico.com/news/2022/03/29/u-s-troops-europe-russia-ukraine-00021296.

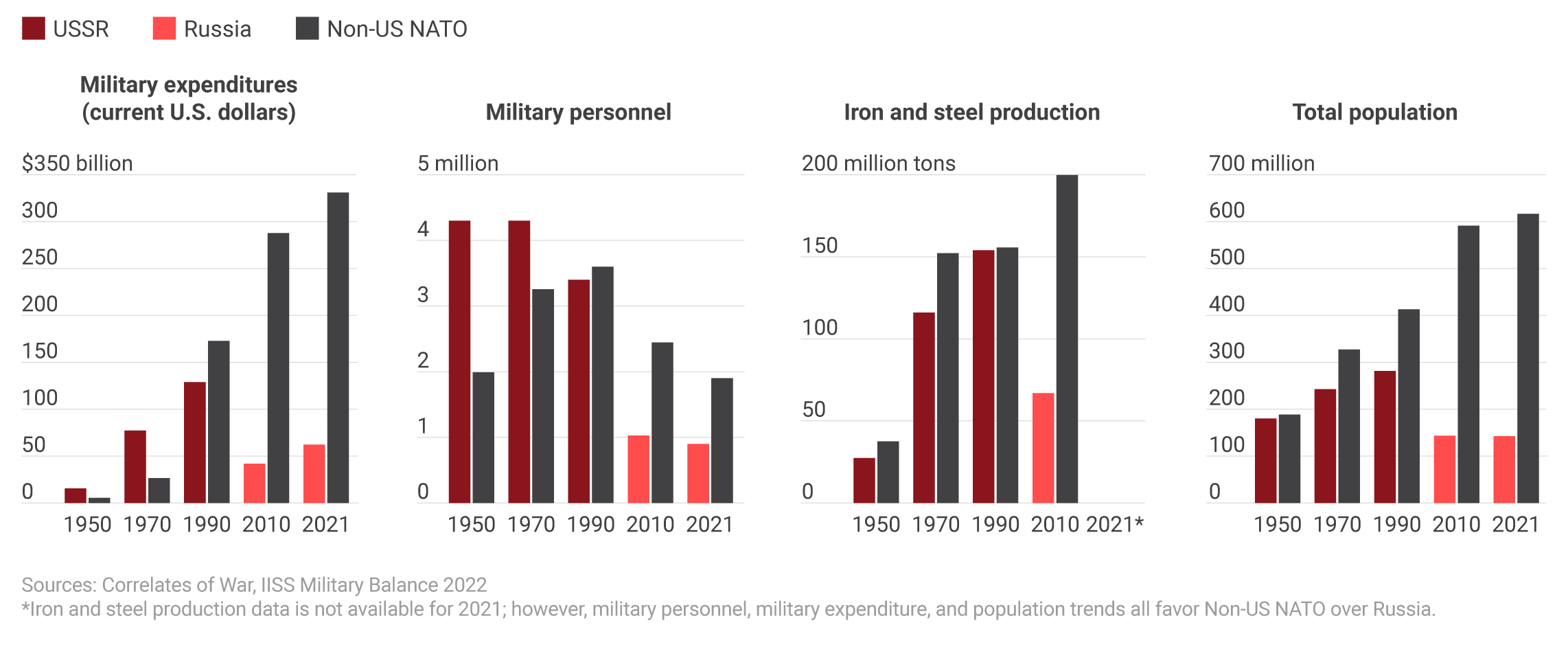

This is despite NATO likely gaining two additional members—one of which, Finland, has one of Europe’s most effective armed forces—since Russia’s attack on Ukraine. Europe possesses abundant resources for organizing an effective defense against Russia, as some standard measures of power make clear.33Heljä Ossa, Tommi Koivula, “What Would Finland Bring to the Table for NATO?” War on the Rocks, May 9, 2022, https://warontherocks.com/2022/05/what-would-finland-bring-to-the-table-for-nato/. In 2021, Russia’s GDP (measured in purchasing power parity so as to avoid exchange rate distortions) was a mere 22 percent of the EU’s.34“European Union GDP,” Trading Economics, https://tradingeconomics.com/european-union/gdp. The EU can be used as a convenient proxy for European NATO because of the substantial overlap in membership between the two organizations.

Russia has always been determined to exert its influence on its neighbors, above all Ukraine, but the threat that countries pose requires capacity, not merely intent. Russia’s capacity has diminished substantially and, in any event, is something that Europe, given the political will, can counter. The war in Ukraine, contrary to prevailing belief, does not prove otherwise and, if anything, exposes Russia’s numerous military weaknesses.

Why Europe can defend itself

Aside from economic resources as indicated by GDP, Europe also has many world-class defense industries that produce and export an array of major armaments.35Alexander Roth, “The Size and Location of Europe’s Defence Industry,” Bruegel, June 22, 2017, https://www.bruegel.org/blog-post/size-and-location-europes-defence-industry. Europe’s technological prowess in areas that will be at the forefront in this century also far exceeds that of Russia, which remains primarily a hydrocarbon-based economy.

Non-U.S. NATO, Soviet Union, and Russia power comparison

The discrepancy between non-U.S. NATO and Russia’s power capabilities since the end of the Cold War shows Europe is more than capable of defending itself.

Of Russia’s top 10 exports, which comprise nearly 70 percent of the total, oil and gas comprise over 40 percent.36Daniel Workman, “Russia’s Top 10 Exports,” World’s Top Exports, https://www.worldstopexports.com/russias-top-10-exports/. Raw materials, except for iron and steel (2 percent) and plastics (just over 1 percent) comprise the rest. Europe’s leading exports, by contrast, are machinery, pharmaceuticals, computer and related equipment, and electronics.37“Main Goods in Extra-EU exports,” Eurostat, March 2022, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Main_goods_in_extra-EU_exports. In a 2022 ranking of countries based on technological advancement Russia placed 41st; by contrast, 8 of the top 14 were European.38Marc Getzoff, “Most Technologically Advanced Countries in the World 2022,” Global Finance, May 4, 2022, https://www.gfmag.com/global-data/non-economic-data/best-tech-countries.

Furthermore, Europe has world-class capabilities in the technologies that will transform warfare over the next several decades, including artificial intelligence, quantum computing, cybertechnology, portable electronic devices, and battlefield-relevant software.39Dominik P. Jankowski, “Russia and the Technological Race in an Era of Great Power Competition,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, September 14, 2021, https://www.csis.org/analysis/russia-and-technological-race-era-great-power-competition. Russia, by contrast, is lagging behind the world’s leaders and struggling to keep up because of shortfalls in resources, the decline in the caliber of its STEM education and research and development, and various institutional impediments.

Nor does Europe lack defense industries that can produce state-of-the art combat aircraft, warships and submarines, armor, and air defenses. European countries accounted for eight of world’s 25 leading arms exporters between 2016 and 2020, and six placed within the top 15. As noted previously, cross-border collaboration in research and development, joint ventures, and reduced duplication by agreeing on a division of labor (to the extent feasible) can make European defense production even more robust. And, of course, Europe has the means to continue purchasing U.S. armaments to build up its military power.

“Strategic cacophony” does not preclude burden shifting

One prominent argument against reallocating responsibility within NATO is that greater European defense autonomy is precluded by Europe’s “strategic cacophony” (multiple, presumably irreconcilable, national viewpoints on security) and “severe military capacity shortfalls.”40Hugo Meijer and Stephen G. Brooks, “Illusions of Autonomy: Why Europe Cannot Provide for Its Security If the United States Pulls Back,” International Security 45, no. 4 (2021): 7–43. https://direct.mit.edu/isec/article/45/4/7/100571/Illusions-of-Autonomy-Why-Europe-Cannot-Provide. The claim about strategic cacophony doesn’t withstand scrutiny, as the history of the EU’s integration demonstrates. Like NATO, the EU comprises many sovereign states—27 to be precise—that have different histories, outlooks, and interests. Yet, through collective action, the EU has achieved a depth of integration few would have thought possible a few decades ago.

The examples include a common currency (that most members have adopted), a central bank, a single market, and the abolition of border controls under the Schengen Agreement, which 26 EU states have signed.41“Schengen (Agreement and Convention),” Eur-Lex, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/EN/legal-content/glossary/schengen-agreement-and-convention.html. These advances toward supranationalism required relinquishing some key attributes of state sovereignty—such as a national currency, a central bank, and control over borders—that involved changes that are politically much more demanding to implement than the ideas for reconfiguration proposed here. Yet the EU was able to overcome national differences and collective action problems.

Strategic cacophony is therefore not akin to the laws of gravity or some congenital European trait. It stems from Europe’s long-time strategic infantilization, itself a byproduct of the codependency that has characterized NATO. It is a condition enabled by the degree of Europe’s longtime dependence on the United States. Alliances have always involved separate states with different outlooks on security, yet that has not prevented coordinated action. Likewise, wealthy and technologically advanced countries like those in Europe are certainly capable of overcoming capacity shortfalls. The shortfall that exists in Europe is certainly not resources; it’s the political will to harness resources to acquire a more effective defense capability.

But strategic autonomy will not happen in Europe without burden shifting, a drawdown of U.S. forces as a sign of its reduced commitments to defend the continent. So long as the United States continues regards itself as “the indispensable nation” that must underwrite the security of countries and regions worldwide regardless of their wealth and military capacity, Europe will not organize itself to contribute meaningfully to any effort to balance against, or deter threats from, Russia.

Why Europe should shoulder the burden

Neither “strategic cacophony,” “severe military shortfalls,” nor Russia’s invasion of Ukraine are insuperable barriers to burden shifting. It is, however, reasonable to ask why Europe should spend more on self-defense and take steps such as coordinated weapons production, as this explainer recommends, if the Russian army is in fact as weak as the war in Ukraine has revealed. There are at least three answers to this question.

First, the sharp reduction in Washington’s role in defending Europe proposed here should encourage Europe to acquire important military capabilities for which it has relied on the United States for a generation. To be sure, Europe can choose to do without them, but that seems unlikely given the long-term needs to ensure Europe’s security against threats that are not visible now but could emerge.

Second, Europe may conclude that it should prepare for the possibility that Russia may, as it has shown itself capable of doing repeatedly in the course of its long history, acquire the military capabilities that enable it to pose a threat, and that the lesson it will take from its invasion of Ukraine is not that it must rein in its territorial ambitions but that it must address the problems that the war has revealed so that it can eventually realize those ambitions.

Third, NATO countries in East-Central Europe—notably Poland and the Baltic states—have been attacked, annexed, or dominated by Russia and will almost certainly take the view that Russia represents a continuing threat to Europe’s security, and that perspective will become even more prominent if Ukraine joins NATO. Thus, there will be a group of countries in NATO-Europe that will push for greater defense spending, especially if the U.S. reduces its role in defending Europe.

Ultimately, however, Europeans must be the ones who judge what security challenges they face now and are likely to face in the future. They are certainly entitled to conclude that Russia remains a threat, even after the military weaknesses of Russia were revealed by its war against Ukraine. Whatever their conclusion, formulating a defense strategy and acquiring the military means to make it effective should be primarily NATO-Europe’s responsibility, although burden shifting in no way precludes security cooperation between the United States and Europe in defense of shared interests.

Endnotes

- 1“Number of United States Military Personnel in Europe from 1950 to 2021,” Statista, https://www.statista.com/statistics/1294309/us-troops-europe/.

- 2“‘Prevent the Reemergence of a New Rival’: The Making of the Cheney Regional Defense Strategy, 1991–1992,” National Security Archive, February 26, 2008, https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nukevault/ebb245/.

- 3Rajan Menon, The End of Alliances (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

- 4Sergei Guriev, “Russia’s Constrained Economy: How the Kremlin Can Spur Growth,” Foreign Affairs 95, no. 3 (May/June 2016): 18–22, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43946853.

- 5Henry Foy, “NATO’s Eastern Front: Will the Military Buildup Make Europe Safer?” Financial Times, May 4, 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/a1a242c3-9000-454d-bec7-c49077b2cc6c?shareType=nongift.

- 6Richard Lugar, “NATO: Out of Area or Out of Business; A Call for U.S. Leadership to Revive and Redefine the Alliance,” Richard G. Lugar Senatorial Papers, accessed October 5, 2022, https://collections.libraries.indiana.edu/lugar/items/show/342.

- 7“Kosovo Force,” Military Fandom, https://military-history.fandom.com/wiki/Kosovo_Force#Contributing_states.

- 8“NATO Runs Short of Munitions in Libya: report,” Space War, April 15, 2011, https://www.spacewar.com/reports/NATO_runs_short_of_munitions_in_Libya_report_999.html.

- 9Frederic Wehrey, Burning Shores: Inside the Battle for the New Libya (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2018); Vivian Yee and Mohammed Abdusamee, “After a Decade of Chaos, Can a Splintered Libya Be Made Whole?” New York Times, February 16, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/16/world/middleeast/libya-government-qaddafi.html.

- 10“Defense Spending as a % of Gross Domestic Product (GDP),” U.S. Department of Defense, https://www.defense.gov/Multimedia/Photos/igphoto/2002099941/.

- 11“Germany Military Spending/Defense Budget 1960–2022,” Macrotrends, https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/DEU/germany/military-spending-defense-budget; Michael A. Allen, Michael E. Flynn, and Carla Martinez Machain, “U.S. Global Military Deployments, 1950–2020,” Conflict Management and Peace Science 39, no. 3 (May 2022): 351–370, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/07388942211030885.

- 12“Military expenditure (% of GDP)—Germany,” World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.GD.ZS?locations=DE.

- 13“Military expenditure (% of GDP)—United States,” World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.GD.ZS?locations=US.

- 14Rajan Menon, “The Sorry State of Germany’s Armed Forces,” Foreign Policy, June 18, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/06/18/trump-withdraw-troops-germany-military-spending/.

- 15The record was better on the proportion of defense spending devoted to equipment: Only eight members fell below the 20 percent threshold. “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2021),” NATO, March 31, 2022, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2022/3/pdf/220331-def-exp-2021-en.pdf.

- 16For decades, U.S. leaders have called on European allies to increase defense spending but did little to create the conditions impelling Europe to do so. See Benjamin H. Friedman and Joshua Shifrinson, “Trump, NATO, And Establishment Hysteria,” War on the Rocks, June 16, 2017, https://warontherocks.com/2017/06/trump-nato-and-establishment-hysteria/; U.S. General Accounting Office, ”U.S.-NATO Burden Sharing Allies’ Contributions to Common Defense During the 1980’s,” October 1990, https://www.gao.gov/assets/nsiad-91-32.pdf; James S. Robbins, “Trump’s NATO Heresy Was Eisenhower’s Wisdom: James Robbins,” USA Today, October 3, 2016, https://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2016/10/03/trumps-nato-heresy-eisenhowers-wisdom-james-robbins-column/91282406/; “Rumsfeld Urges Allies to Boost Defense Spending,” NBC News, February 4, 2006, https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna11170234#.WTHsPGjys2w; Ted Galen Carpenter, “NATO, European Spending and US Grievances,” Cato Institute, May 12, 2015, https://www.cato.org/commentary/nato-european-spending-us-grievances.

- 17Colby Lutz, “Burden Sharing Dilemmas and NATO’s Tumultuous Summer,” War Room—U.S. Army War College, September 27, 2018, https://warroom.armywarcollege.edu/articles/natos-tumultuous-summer/.

- 18Hans Binnendijk, Daniel S. Hamilton, and Alexander Vershbow, “Strategic Responsibility: Rebalancing European and Trans-Atlantic Defense,” Brookings Institution, June 24, 2022, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/strategic-responsibility-rebalancing-european-and-trans-atlantic-defense/.

- 19Guy Verhofstadt, “Europe’s Military Weakness is Indefensible!” Euobserver, October 6, 2021, https://euobserver.com/opinion/153129.

- 20“Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2022),” NATO, June 27, 2022, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2022/6/pdf/220627-def-exp-2022-en.pdf.

- 21“Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2021),” NATO, March 31, 2022, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2022/3/pdf/220331-def-exp-2021-en.pdf; Brendan Cole, “Russia Increases Defense Spending by 20% as it Struggles to Replace Weapons,” Newsweek, June 14, 2022, https://www.newsweek.com/ukraine-russia-weapons-defense-sanctions-1715568.

- 22Valerio Briani, “Armaments Duplication in Europe: A Quantitative Assessment,” Centre for European Policy Studies, July 16, 2013, https://www.ceps.eu/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/PB%20297%20Briani%20Duplication%20in%20EU%20armed%20forces%20-.pdf.

- 23Raluca Csernatoni, “The EU’s Defense Ambitions: Understanding the Emergence of a European Defense Technological and Industrial Complex,” Carnegie Europe, December 6, 2021, https://carnegieeurope.eu/2021/12/06/eu-s-defense-ambitions-understanding-emergence-of-european-defense-technological-and-industrial-complex-pub-85884; “Common Security and Defence Policy,” European Parliament, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/factsheets/en/sheet/159/common-security-and-defence-policy; Alexandra Brzozowski, “European Parliament Backs EU’s €7.9 billion Defence Fund,” Euractiv, April 30, 2021, https://www.euractiv.com/section/defence-and-security/news/european-parliament-backs-eus-e7-9-billion-defence-fund/; Gustav Gressel and Nick Witney, “Out of the Dark: Reinventing European Defence Cooperation,” European Council on Foreign Relations, March 18, 2022, https://ecfr.eu/article/out-of-the-dark-reinventing-european-defence-cooperation/.

- 24Michael Birnbaum and Emily Rauhala, “Those 300,000 High-Readiness NATO Troops? ‘Concept,’ Not Reality,” Washington Post, June 29, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/06/29/those-300000-high-readiness-nato-troops-concept-not-reality/.

- 25The issue of NATO defense spending, what it would cost to defend Europe, and the value of redistribution of defense spending for fairness has been addressed by IISS and Barry Posen, among others. See Lucie Béraud-Sudreau and Nick Childs, “The U.S. and Its NATO Allies: Costs and Value,” International Institute of Strategic Studies, July 9, 2018, https://www.iiss.org/blogs/military-balance/2018/07/us-and-nato-allies-costs-and-value; Barry R. Posen, “A New Transatlantic Division of Labor Could Save Billions Every Year!” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, September 7, 2021, https://thebulletin.org/premium/2021-09/a-new-transatlantic-division-of-labor-could-save-billions-every-year/.

- 26Darlene Superville and Zeke Miller, “U.S. Boosting Military Presence in Europe Amid Russia Threat,” ABC News, June 29, 2022, https://abcnews.go.com/International/wireStory/biden-us-boosting-force-posture-europe-russia-threat-85913564.

- 27“Founding Act,” NATO, October 12, 2009, https://www.nato.int/cps/su/natohq/official_texts_25468.htm.

- 28“NATO Response Force,” NATO, July 11, 2016, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/topics_49755.htm; Emily Rauhala and Annabelle Timsit, “NATO to Boost High-readiness Forces in ‘Biggest Overhaul’ Since Cold War,” Washington Post, June 27, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/06/27/nato-rapid-reaction-force-expansion/.

- 29Anton Lavrov, “Russian Military Reforms from Georgia to Syria,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, November 5, 2018, https://www.csis.org/analysis/russian-military-reforms-georgia-syria; Michael Kofman, “Russian Performance in the Russo-Georgian War Revisited,” War on the Rocks, September 4, 2018, https://warontherocks.com/2018/09/russian-performance-in-the-russo-georgian-war-revisited/.

- 30Phil Stewart, “CIA Director Estimates 15,000 Russians Killed in Ukraine War,” Reuters, July 20, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/cia-director-says-some-15000-russians-killed-ukraine-war-2022-07-20/.

- 31Isabel Van Brugen, “Russia Has Lost Over 2,000 Tanks Since War Began—Ukraine,” Newsweek, September 2, 2022, https://www.newsweek.com/russia-tanks-destroyed-war-ukraine-1739258.

- 32“More U.S. Troops May Be Needed, Top General Predicts,” Politico, March 29, 2022, https://www.politico.com/news/2022/03/29/u-s-troops-europe-russia-ukraine-00021296.

- 33Heljä Ossa, Tommi Koivula, “What Would Finland Bring to the Table for NATO?” War on the Rocks, May 9, 2022, https://warontherocks.com/2022/05/what-would-finland-bring-to-the-table-for-nato/.

- 34“European Union GDP,” Trading Economics, https://tradingeconomics.com/european-union/gdp. The EU can be used as a convenient proxy for European NATO because of the substantial overlap in membership between the two organizations.

- 35Alexander Roth, “The Size and Location of Europe’s Defence Industry,” Bruegel, June 22, 2017, https://www.bruegel.org/blog-post/size-and-location-europes-defence-industry.

- 36Daniel Workman, “Russia’s Top 10 Exports,” World’s Top Exports, https://www.worldstopexports.com/russias-top-10-exports/.

- 37“Main Goods in Extra-EU exports,” Eurostat, March 2022, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Main_goods_in_extra-EU_exports.

- 38Marc Getzoff, “Most Technologically Advanced Countries in the World 2022,” Global Finance, May 4, 2022, https://www.gfmag.com/global-data/non-economic-data/best-tech-countries.

- 39Dominik P. Jankowski, “Russia and the Technological Race in an Era of Great Power Competition,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, September 14, 2021, https://www.csis.org/analysis/russia-and-technological-race-era-great-power-competition.

- 40Hugo Meijer and Stephen G. Brooks, “Illusions of Autonomy: Why Europe Cannot Provide for Its Security If the United States Pulls Back,” International Security 45, no. 4 (2021): 7–43. https://direct.mit.edu/isec/article/45/4/7/100571/Illusions-of-Autonomy-Why-Europe-Cannot-Provide.

- 41“Schengen (Agreement and Convention),” Eur-Lex, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/EN/legal-content/glossary/schengen-agreement-and-convention.html.

More on Europe

Featuring Dan Caldwell

November 23, 2025

Events on NATO