Key points

- During the Trump I and Biden presidencies, the United States applied growing pressure on NATO to turn against China. Although focused on protecting Europe, these efforts also attempted to expand the alliance’s prerogatives into the Indo-Pacific.

- Should this expansion continue, it could distract NATO from Russia, the only real threat that Europe faces.

- It could also delay the emergence of a more autonomous Europe able to defend itself, thereby perpetuating current U.S. overstretch and reducing Washington’s ability to concentrate on the China challenge in Asia.

- NATO’s turn against China might generate undue tensions with the PRC, deepen Sino-Russian cooperation, and cause controversy in the Global South, all of which would work against U.S. interests.

- Instead of trying to fold Europe and Asia together to counter the Sino-Russian axis along the Eurasian rimland, the U.S. should keep NATO focused on Russia and encourage European strategic autonomy. It should refocus its own efforts on the Indo-Pacific and reduce the risk of escalation with Beijing.

The push for NATO involvement in the Indo-Pacific

During the Trump I and Biden presidencies, U.S. leaders increasingly pressed NATO to shift its attention to the People’s Republic of China (PRC). This approach is misguided, however, and risks weakening Europe’s security and preventing the United States from reorienting its attention to more pressing needs in Asia.

Despite President Trump’s skepticism of the Western alliance, his administration urged NATO to align with the hardening of America’s China strategy after January 2017.1Lisa Ferdinando, “Mattis Highlights US Commitment to NATO, Warns of ‘Arc of Insecurity,’” DOD News, February 15, 2017, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/1084785/mattis-highlights-us-commitment-to-nato-warns-of-arc-of-insecurity/. To achieve this, Washington portrayed the PRC as a competitor seeking to “challenge American power, influence, and interests,” “change the international order in [its] favor,” and “displace the United States in the Indo-Pacific region.”2“National Security Strategy of the United States of America,” White House, December 2017, 2, 25, 27, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905.pdf. It strongly condemned Beijing’s efforts to “gain a strategic foothold in Europe by expanding its unfair trade practices and investing in key industries, sensitive technologies, and infrastructure.”3Luis Simón, Linde Desmaele, and Jordan Becker, “Europe as a Secondary Theater? Competition with China and the Future of America’s European Strategy,” Strategic Studies Quarterly, vol. 15, issue 1 (Spring 2021): 94, https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/SSQ/documents/Volume-15_Issue-1/Simon.pdf. More specifically, the Trump administration argued that the PRC’s acquisition of leading European companies, investments in local port facilities, and construction of local 5G internet networks could one day threaten NATO’s mobility, interoperability, supply chains, communications, and intelligence-sharing.4Elsa B. Kania, “Securing Our 5G Future: The Competitive Challenge and Considerations for US Policy,” Center for a New American Security, November 7, 2019, 13, 20–21, https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/securing-our-5g-future; Adam Segal, “Huawei, 5G, and Weaponized Interdependence,” in eds. Daniel W. Drezner, Henry Farrell, and Abraham L. Newman, The Uses and Abuses of Weaponized Interdependence (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2021), 154.

For all the controversies it triggered along the way, the Trump administration scored notable successes on this front, as illustrated by NATO’s decision to include the PRC on its agenda in April 2019 and Europe’s growing pushback against Huawei’s bids to develop 5G networks across the continent.5Jengs Ringsmose and Stenn Rynning, “China Brought NATO Closer Together,” War on the Rocks, February 5, 2020, https://warontherocks.com/2020/02/china-brought-nato-closer-together/; David Hutt, “Huawei Losing its 5G Grip on Europe,” Asia Times, July 17, 2020, https://asiatimes.com/2020/07/huawei-losing-its-5g-grip-on-europe/. Although it did not specifically aim for inter-theater cooperation, the Trump administration’s push against China in Europe laid the groundwork for a gradual rapprochement between NATO and Washington’s Indo-Pacific allies.6Lotje Boswinkel et al., “Alliance Networking in Europe and the Indo-Pacific,” War on the Rocks, December 17, 2024, https://warontherocks.com/2024/12/alliance-networking-in-europe-and-the-indo-pacific/.

President Biden endorsed his predecessor’s stance on the PRC and quickly sought to expand NATO’s turn against Beijing. Combined with his efforts to repair the American alliance network and recommit the U.S. to the so-called “liberal order,” this campaign produced swift outcomes. NATO’s 2021 annual summit communiqué claimed that “China’s stated ambitions and assertive behavior present[ed] systemic challenges to the rules-based international order and to areas relevant to Alliance security.” Thus the organization committed to engaging Beijing “with a view to defending the security interests of the Alliance” in areas such as economic security, telecommunications, and freedom of navigation.7“Brussels Summit Communiqué,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, June 14, 2021, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_185000.htm.

This momentum accelerated following the outbreak of the war in Ukraine in February 2022. First, Washington leveraged the historic joint statement that Xi Jinping had co-signed with Vladimir Putin a few weeks earlier, which condemned NATO’s enlargement (a first for the PRC), proclaimed a friendship without “forbidden’ areas,” and pledged cooperation “against attempts by external forces to undermine… stability in their common adjacent regions.”8“Joint Statement of the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China on the International Relations Entering a New Era and the Global Sustainable Development,” President of Russia, February 4, 2022, http://en.kremlin.ru/supplement/5770#sel=1:21:S5F,1:37:3jE. Second, the Biden administration used its pivotal role in the West’s campaign in support of Ukraine to press European leaders to further harden their policies against China, including growing restrictions on Chinese economic and political activities in Europe, a stronger endorsement of Washington’s tech war on the PRC, and “an active role in the Indo-Pacific [on issues such as] supporting freedom of navigation and maintaining peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait.”9Edward Luce, “The World According to NATO,” Financial Times, December 2, 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/72445197-ea9b-43df-bc3a-e0b06832695a; “National Security Strategy,” White House, October 2022, 17, https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Biden-Harris-Administrations-National-Security-Strategy-10.2022.pdf. In parallel, the Biden administration requested that its Asian allies sanction Russia and back Ukraine.10Jack Detsch, “Biden Enlists Asian Partners for Unprecedented Russia sanctions Plans,” Foreign Policy, February 22, 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/02/22/biden-russia-ukraine-sanctions-asia-allies-export-controls-invasion-plans/.

This U.S. push led European leaders to support the development of nascent linkages between NATO and the Indo-Pacific. For example, in 2019, NATO initiated new programs in domains such as 5G and outer space with the PRC and America’s Asian allies in mind.11“NATO 2030: United for a New Era,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, November 25, 2020, 47, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2020/12/pdf/201201-Reflection-Group-Final-Report-Uni.pdf. In parallel, the EU and leading European states such as the UK, France, and Germany published their first Indo-Pacific strategies.12Marianne Schneider-Petsinger et al., “Transatlantic Cooperation on the Indo-Pacific: European and US Priorities, Partners, and Platforms,” Chatham House, November 2022, 2–5, https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/2022-11/2022-11-17-transatlantic-cooperation-indo-pacific-schneider-petsinger-et-al.pdf. They also increased their arms sales and naval presences in the region, as illustrated in 2021 by the dispatch of a French nuclear-propelled attack submarine to the South China Sea, the patrol of a British carrier strike group across the Western Pacific, and the first German frigate deployment in two decades, which ended its six-month journey in Japan, Washington’s closest ally in the region.13On European arms sales, see Luis Simón, “Europe, the Rise of Asia and the Future of the Transatlantic Relationship,” International Affairs, vol. 91, issue 5 (September 2015): 986, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24539014; on European naval deployments, see Jan Gerber, “NATO Should Defend Europe, Not Pivot to Asia,” Defense Priorities, February 18, 2022, 3, https://www.defensepriorities.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/DEFP_NATO_should_defend_Europe_not_pivot_to_Asia.pdf.

In 2021, America’s NATO allies deployed a record 21 ships (in addition to those of the U.S. Seventh Fleet) in maritime Asia. Although their modalities were varied, these deployments were designed to emphasize the need for stability in a clear, if often implicit, reference to China’s assertiveness. Going even further, the UK forged the AUKUS partnership, agreeing to jointly develop nuclear submarines and disruptive technologies with the U.S. and Australia. It also committed to “project cutting-edge military power [in maritime Asia] in support of NATO.”14Gerber, “NATO Should Defend Europe,” 1–3.

The new Strategic Concept adopted by NATO in June 2022 recognized how “developments” in the Indo-Pacific could “directly affect Euro-Atlantic security.”15“NATO 2022 Strategic Concept,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, June 29, 2022, 11, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2022/6/pdf/290622-strategic-concept.pdf. In November of that year, the Western alliance held its first ever meeting explicitly dedicated to the threat the PRC posed to Taiwan.16Henry Foy and Demetri Sevastopulo, “NATO Holds First Dedicated Talks on China Threat to Taiwan,” Financial Times, November 30, 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/d7fa2d2b-53be-4175-bf2b-92af5defa622. In July 2023, it launched Individually Tailored Partnership Programs (ITPPs) with Australia, Japan, and South Korea to enhance interoperability and cooperation in emerging technologies.17Hae-Won Jun, “NATO and its Indo-Pacific Partners Choose Practice Over Rhetoric,” RUSI, December 5, 2023, https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/nato-and-its-indo-pacific-partners-choose-practice-over-rhetoric-2023.

European states increased their strategic cooperation with America’s Asian allies and partners, as exemplified by France’s announcement of a joint vision for the Indo-Pacific with India, Britain’s conclusion of a reciprocal access defense agreement with Japan, and Britain’s Global Combat Air Program (GCAP) with Italy and Japan, designed to produce a next-generation fighter aircraft by 2035.18On the French-Indian visions, see Léonie Allard, “Deciphering French Strategy in the Indo-Pacific,” War on the Rocks, March 13, 2025, https://warontherocks.com/2025/03/deciphering-french-strategy-in-the-indo-pacific/; on the Anglo-Japanese agreement, see Alistair Smout, “Britain, Japan Sign Defence Pact During PM Kishida Visit to London,” Reuters, January 11, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/britain-japan-sign-defence-pact-during-pm-kishida-visit-london-2023-01-11/; on the GCAP, see Alessio Patalano and Peter Watkins, “‘LEAP’ Forward: Building a GCAP Generation,” King’s College London, March 2024, 5, https://www.kcl.ac.uk/warstudies/assets/paper-21-alessio-patalano-and-peter-watkins-‘leap’-forward.pdf.

They also continued their deployments in the Indo-Pacific, which included the participation of seven European countries in the United States’ Rim of the Pacific exercises (RIMPAC) in June 2024, the world’s biggest multinational maritime drills.19Jakub Witczak, “Time for a New Normal – Enhancing Europe’s Military Profile in the Indo-Pacific in 2025,” Boym Institute, January 8, 2025, https://instytutboyma.org/en/time-for-a-new-normal-enhancing-europes-military-profile-in-the-indo-pacific-in-2025-2/.

The NATO administration consolidated this reorientation throughout, eager to demonstrate its enduring relevance as the U.S. turned its attention to Asia.20Jeffrey H. Michaels, “‘A Very Different Kind of Challenge’? NATO’s Prioritization of China in Historical Perspective,” International Politics, vol. 59, issue 6 (2022): 1046–1047, https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-021-00334-z. In line with Washington’s cues, then-secretary general Jens Stoltenberg declared misguided the “whole idea of… distinguishing so much between China, Russia, either Asia-Pacific or Europe. It’s one big security environment, and we have to address it all together.”21Interview conducted by Roula Khalaf and Henry Foy, “Transcript: ‘China Is Coming Closer to Us’ — Jens Stoltenberg, NATO’s Secretary-General,” Financial Times, October 18, 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/cf8c6d06-ff81-42d5-a81e-c56f2b3533c2. He also evoked the threat that the PRC’s nuclear buildup and the emergence of a Sino-Russian nuclear dual front could pose to the alliance.22Dan Sabbagh, “Row as Nato Chief Hints at Talks to Increase Availability of Nuclear Weapons,” Guardian, June 17, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/world/article/2024/jun/17/row-as-nato-chief-hints-at-talks-to-increase-availability-of-nuclear-weapons. Expanding the agenda further, then-NATO supreme allied commander Christopher Cavoli called for European and Asian states to collaborate closely against the “interlocking, strategic partnerships” that China had forged with Russia, Iran, and North Korea during the Ukraine war.23Jim Garamone, “US Commander in Europe Says Russia Is a ‘Chronic Threat to World,” U.S. Department of Defense, April 10, 2024, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3737446/us-commander-in-europe-says-russia-is-a-chronic-threat-to-world/.

The return of Donald Trump to the White House in January 2025 has revived uncertainties about NATO’s future as the new Republican administration initiated talks with Russia over Ukraine without the EU and signaled its interest in a significant (if not drastic) reduction of the American contribution to Europe’s security.24On talks with Russia, see “Europe Will Not Be Part of Ukraine Peace Talks, US Envoy Says,” Reuters, February 25, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/zelenskiy-calls-european-army-deter-russia-earn-us-respect-2025-02-15/; on Trump’s interest in a drawdown, see John Vandiver, “Trump Aims to Cut US Forces with 20,000,” Real Clear Defense, January 25, 2025, https://www.realcleardefense.com/2025/01/25/trump_aims_to_cut_us_force_in_europe_by_20000_1087108.html. Additionally, the new administration suggested it “would much prefer that the overwhelming balance of European investment be on that continent” to allow the U.S. to use its “comparative advantage as an Indo-Pacific nation to support” its regional partners.25Li Xueying, “Europe’s top diplomat rejects Pentagon chief’s call that it limits role in Asia,” Straits Times, June 1, 2025, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/europes-top-diplomat-rejects-pentagon-chiefs-call-that-it-limits-role-in-asia.

However, there is no guarantee that Washington will cease its efforts to push NATO against China in both Europe and Asia. Although today’s context differs from 2017–2021, NATO was strengthened in important respects during the first Trump presidency, as exemplified by Washington’s efforts to enhance the alliance’s readiness, its full support to the European Deterrence Initiative, and its strident calls for higher European military budgets.26On NATO’s readiness, see Anthony H. Cordesman, “The US, NATO, and the Defense of Europe: Underlying Trends,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 27, 2018, 3, https://www.csis.org/analysis/us-nato-and-defense-europe-underlying-trends; on the European Deterrence Initiative, see James Sperling and Mark Webber, “Trump’s Foreign Policy and NATO: Exit and Voice,” Review of International Studies, vol. 45, issue 3 (2019): 523–525, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210519000123. Those budgets did go up, perhaps due more to growing tensions with Putin’s Russia over Ukraine and other issues.27Daniel Kochis, “NATO Allies Now Spend 50 Billion More on Defense Than in 2016,” Heritage Foundation, November 3, 2020, https://www.heritage.org/defense/commentary/nato-allies-now-spend-50-billion-more-defense-2016. The first Trump administration fiercely opposed any hint of European strategic autonomy.28Linda Desmaele, Europe’s Evolving Role in US Grand Strategy: Indispensable or Insufferable (New York: Routledge, 2024), 132–133. Additionally, as illustrated by its threat not to “partner alongside” the states that would authorize Huawei’s 5G internet networks, it used the prospect of a potential disengagement from NATO to incentivize European leaders to endorse America’s China policy.29On the Huawei controversy, see “NATO at 70: Where Next?” Politico, April 3, 2019, https://www.politico.eu/article/nato-at-70-where-next/; on the threat of disengagement, see Stephen M. Walt, “Europe’s Future Is as China’s Enemy,” Foreign Policy, January 22, 2029, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/01/22/europes-future-is-as-chinas-enemy/. This could continue now that Beijing is looming even more prominently on the U.S. agenda.

Despite a raucous start, the Trump II administration has gradually tempered its hostility toward NATO, which can be attributed to U.S. concerns about a potential decline in American military exports to the region, the possibility of a European nuclear buildup, but also the prospect of a China-Europe rapprochement.30Jennifer Kavanagh and Daniel DePetris, “More European Defense Spending Isn’t Cause for Celebration,” Stars and Stripes, July 2, 2025, https://www.stripes.com/opinion/2025-07-02/europe-defense-spending-increase-dont-celebrate-opinion-18314261.html. Despite its statements in favor of a geographic division of labor, the Trump administration might still be tempted to promote inter-theater cooperation, as suggested by Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth’s acknowledgment that European militaries could be “useful” to influence the PRC’s “calculus” in the Indo-Pacific.31Noah Robertson, “Europeans Map Out Pacific Aims as Some in US Want Then to Stay Home,” Defense News, June 3, 2025, https://www.defensenews.com/pentagon/2025/06/03/europeans-map-out-pacific-aims-as-some-in-us-want-them-to-stay-home/.

Meanwhile, despite the shock prompted by the Trump II administration’s relative hostility, European leaders might once again endorse expanding NATO’s agenda in Asia to retain Washington’s favor instead of repairing their relationship with China or making the sacrifices necessary for the emergence of a genuine EU strategic autonomy.32Ringsmose and Rynning, “China Brought NATO Closer Together.” This may prove counterproductive if not dangerous, as shown by several inherent problems discussed below.

Problem 1: Weakening NATO’s cohesion

The U.S. push to strengthen NATO’s stance toward China could create more tensions within the alliance, thereby weakening its cohesion.

As noted, European leaders have lately accommodated America’s demands regarding NATO’s approach to China and the Indo-Pacific. This is not only because they view cooperation with the United States on that topic as an acceptable price to retain the U.S. security umbrella in Europe, but also because some of them agree with the reasoning behind such calls. France and the United Kingdom have significant territories, populations, and military assets in the Indo-Pacific region.33Philippe Le Corre, “Can France and the UK Pivot to the Pacific?” Expressions, Institut Montaigne, July 19, 2018, https://www.institutmontaigne.org/en/expressions/can-france-and-uk-pivot-pacific. EU members all have deep economic interests in that part of the world.34Patrick Allard and Frédéric Grare, “European Trade and Strategy in the Indo-Pacific: Why the EU Should Join the CPTPP,” European Council on Foreign Relations, December 1, 2021, https://ecfr.eu/article/european-trade-and-strategy-in-the-indo-pacific-why-the-eu-should-join-the-cptpp/. Moreover, a war in Asia could conceivably lead the PRC to attack the U.S. homeland, thereby triggering Article 5 of the NATO charter—an attack on one is an attack on all.35Michael J. Mazarr, “Why America Still Needs Europe: The False Promise of an ‘Asia First’ Approach,” Foreign Affairs, April 17, 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/why-america-still-needs-europe. Any putative U.S. conflict with China in Asia would likely have “ripple effects throughout global supply chains” and trigger a global economic depression.36Masayuki Masuda, “The Long Shadow? China’s Military Rise in the Indo-Pacific and its Global Implications,” Center for Security, Diplomacy, and Strategy, June 21, 2024, https://csds.vub.be/publication/the-long-shadow-chinas-military-rise-in-the-indo-pacific-and-its-global-implications/.

Yet despite their concerns about Beijing and their desire to appease Washington, European leaders have always had good reasons to reject U.S. alarmism. Europe’s geographic distance from maritime Asia naturally softens its threat perceptions regarding the PRC’s military buildup.37Stephen M. Walt, “Will Europe Ever Really Confront China,” Foreign Policy, October 15, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/10/15/will-europe-ever-really-confront-china/. Moreover, despite its historic decision in March 2019 to declare China a “systemic rival” (among other designations), the EU, due in part to its greater openness to international trade and its less stringent protection mechanisms, is especially sensitive to the PRC’s economic appeal.38“Europe Can’t Decide How to Unplug from China,” Economist, May 15, 2023, https://www.economist.com/international/2023/05/15/europe-cant-decide-how-to-unplug-from-china; Agatha Kratz, Camille Boullenois, and Jeremy Smith, “Why Isn’t Europe Diversifying from China,” Rhodium Group, December 2, 2024, 9–10, https://rhg.com/research/why-isnt-europe-diversifying-from-china/.

In contrast to America’s elites, eager to maintain global hegemony, the Europeans, whose international influence has been dwindling for decades, are more at ease with the idea of relative decline.39Janan Ganesh, “Why Europe and America Will Always Think Differently on China,” Financial Times, April 18, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/e007e9c4-81de-49ff-8bee-2776a06eaec8. Additionally, Europe lacks a defense industry—or military-industrial complex—with anything like the political influence of the U.S. version, which is using China’s rise to justify its growing funding and influence.40Fareed Zakaria, “The Pentagon is Using China as An Excuse for Huge New Budgets,” Washington Post, March 18, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/the-pentagon-is-using-china-as-an-excuse-for-huge-new-budgets/2021/03/18/848c8296-8824-11eb-8a8b-5cf82c3dffe4_story.html. Most importantly, Europe faces recurrently unstable neighborhoods on its eastern and southern flanks. The war in Ukraine has led some of its leaders (especially in Eastern Europe) to worry that NATO’s growing interest in maritime Asia could divert its attention from Russia.41Steven Erlanger and Michael D. Shear, “Shifting Focus, NATO Sees China as a Global Security Challenge,” New York Times, June 14, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/14/world/europe/biden-nato-china-russia.html.

These factors have prompted European leaders to adopt a relatively calm reading of the China challenge. They’ve acknowledged that Beijing has not been directly involved in a war since 1979, that its defense budget is still much lower than America’s, that its capacity to project power across oceans is still limited, and that it still faces powerful rivals and a complex geographic environment in its immediate vicinity.42On China’s military budget, see M. Taylor Fravel, George J. Gilboy, and Eric Heginbotham, “Estimating China’s Defense Spending: How to Get It Wrong (and Right),” Texas National Security Review, vol. 7, issue 3 (Summer 2024): 42, https://tnsr.org/2024/06/estimating-chinas-defense-spending-how-to-get-it-wrong-and-right/; on China’s power projection capacity, see Mike Sweeney, “Challenges to Chinese Blue-Water Operations,” Defense Priorities, April 30, 2024, 1–27, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/challenges-to-chinese-blue-water-operations/; on China’s local rivals, see Daniel Davis, “Responsibly Competing with China,” Defense Priorities, July 29, 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/responsibly-competing-with-china/; on China’s geographic environment, see Robert S. Ross, “The Geography of the Peace: East Asia in the Twenty-First Century,” International Security 3, no. 4 (Spring 1999): 81–118, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2539295.

As such, America’s pressure on NATO to strengthen its China policies and become more involved in Asia has often antagonized—or at least divided—European leaders, leading them to keep a degree of distance from Washington. Their military deployments to the Indo-Pacific have consistently been more restrained than those of the United States. For instance, in sharp contrast with their U.S. counterpart, the French and British navies have refused to send patrols within 12 nautical miles of the areas contested by Beijing.43Nicola Casarini, “Rising to the Challenge: Europe’s Security Policy in East Asia Amidst US-China Rivalry,” International Spectator 55, no. 1 (2020): 85–86, 88, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03932729.2020.1712133; Marianne Riddervold and Guri Rosén, “Unified in Response to Rising Powers? China, Russia and EU-US Relations,” Journal of European Integration 40, issue 5 (2018): 563–564, https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2018.1488838.

Furthermore, European leaders have frequently voiced concerns regarding Washington’s assertive and military-centric Indo-Pacific policies. For example, during the NATO summit of June 2021, U.S. leaders had to exert pressure to toughen the alliance’s final communiqué on China.44Dan Sabbagh and Julian Borger, “NATO Summit: Leaders Declare China Presents Security Risks,” Guardian, June 14, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jun/14/nato-summit-china-russia-biden-cyber-attacks. Moreover, whereas some allies (especially in Eastern Europe and the Baltic region) omitted the PRC from their respective statements, German Chancellor Angela Merkel insisted that Beijing would remain a “partner on many issues” and French President Emmanuel Macron stated that “China ha[d] little to do with the North Atlantic.”45On the omissions made by some European allies, see David M. Herszenhorn and Rym Momtaz, “NATO Leaders See Rising Threats from China, But Not Eye to Eye with Each Other,” Politico, June 14, 2021, https://www.politico.eu/article/nato-leaders-see-rising-threats-from-china-but-not-eye-to-eye-with-each-other/; on Merkel’s statement, see Markus Kaim and Angela Stanzel, “The Rise of China and NATO’s New Strategic Concept,” NATO Defense College, March 1, 2022, 2, https://www.ndc.nato.int/news/news.php?icode=1659; on Macron’s statement, see Herszenhorn and Momtaz, “NATO Leaders See Rising Threats from China.”

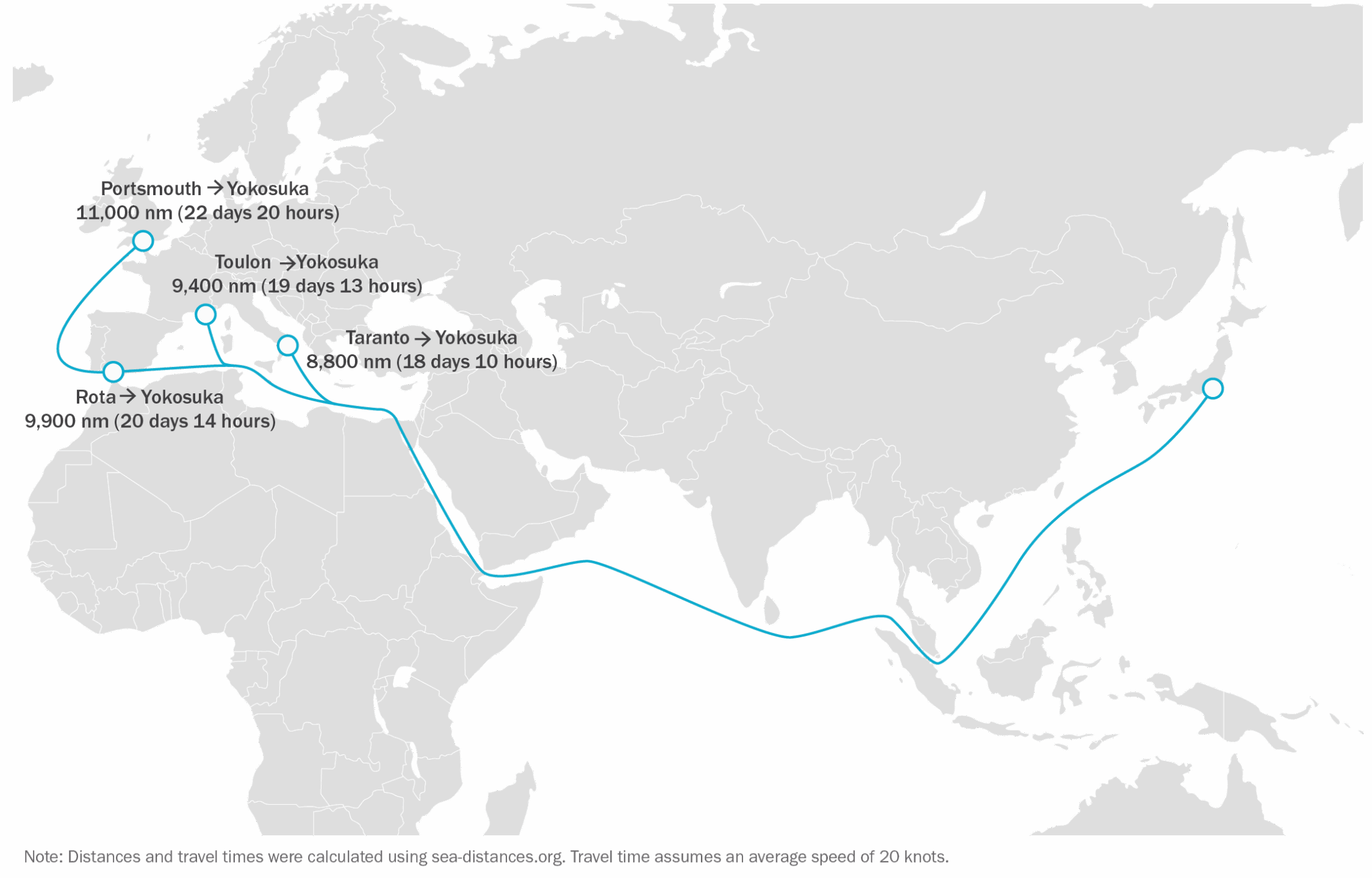

European port distances from maritime Asia

With its major ports thousands of nautical miles away, European nations are disinclined towards China threat inflation. (This graphic uses Yokosuka, Japan, as a destination because it hosts a U.S. naval base where European vessels have docked.)

Washington’s AUKUS partnership with Australia and the UK further complicated efforts to align U.S. and European policy on China, as the deal, which was negotiated in secret, required Canberra to cancel a $66 billion contract concluded a few years earlier to procure French diesel submarines and signaled a growing American assertiveness against the PRC.46Dustin Jones, “Why a Submarine Deal Has France at Odds With the US, UK and Australia,” NPR, September 19, 2021, https://www.npr.org/2021/09/19/1038746061/submarine-deal-us-uk-australia-france. AUKUS caused outrage in Paris, dismayed many other European capitals, and led Charles Michel, the President of the European Council, to condemn an attempt to “put Europe out of the game in the Indo-Pacific.”47Charles Michel, cited in David M. Herszenhorn, “EU Leaders Accuse Biden of Disloyalty to Allies,” Politico, September 21, 2021; https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-charles-michel-biden-disloyalty-allies-aukus. Moreover, the EU’s first Indo-Pacific strategy announced the same week aimed to be “inclusive” and prioritized “cooperation not confrontation” with Beijing.48“Questions and Answers: EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific,” European Commission, September 16, 2021, 2, https://international-partnerships.ec.europa.eu/document/download/016959ed-ee16-498b-842b-0b0395b851de_en?filename=Questions_and_Answers__EU_Strategy_for_Cooperation_in_the_Indo-Pacific.pdf. Beyond their frustrations with Washington’s policies, some European leaders also considered it essential to maintain an independent line to enable the EU to gradually assert its “strategic autonomy” vis-à-vis the U.S.49Schneider-Petsinger et al., “Transatlantic Cooperation on the Indo-Pacific,” 4–5. Thus, in the following weeks, Brussels made clear it would “pursue [its] own interests, in particular, vis-à-vis China.”50Samuel Petrequin, “EU Leaders Discuss Defense, US and China Relationships,” Associated Press, October 5, 2021, https://apnews.com/article/aukus-european-union-emmanuel-macron-australia-brussels-3d5fe748ea01c0f61c7316fed46d6954.

Although the shock caused by the Ukraine war initially helped both sides of the Atlantic close ranks against the PRC, tensions have persisted. For instance, European leaders complained about then-U.S. speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi’s provocative trip to Taiwan in August 2022.51Max Bergmann, “The Transatlantic Alliance in the Age of Trump: The Coming Collisions,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, February 14, 2025, 12, https://www.csis.org/analysis/transatlantic-alliance-age-trump-coming-collisions. Paris opposed NATO’s plan to open a liaison office in Japan in August 2023, a stance that received the tacit support of Germany and some Southern European states.52Lynn Kuok, “NATO Is on the Backfoot in the Indo-Pacific,” Foreign Policy, August 10, 2023, https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/08/10/nato-indo-pacific-china-australia-japan/; Daniel Michaels, “China’s Support for Russia’s War in Ukraine Puts Beijing on NATO’s Threat List,” Wall Street Journal, July 7, 2024, https://www.wsj.com/world/china-nato-threat-list-russia-ukraine-war-47ec07c8. More broadly, most of the region’s NATO members remained lukewarm about the Biden administration’s efforts to put Taiwan contingency scenarios on the alliance’s agenda.53Noah Barkin and Andrew Small, “Congressional Testimony: Aligning Transatlantic Approaches on China,” German Marshall Fund, June 7, 2023, https://www.gmfus.org/news/congressional-testimony-aligning-transatlantic-approaches-china.

Problem 2: Wasting limited European resources in the Indo-Pacific

From a technical perspective, greater NATO involvement could lead to a rise in the number of U.S.-friendly military assets positioned against China. In that regard, recent think tank studies have explained how France and Britain could enhance America’s nuclear submarine fleet by 15 to 20 percent. They also speculated about the participation of European forces in the Indo-Pacific, the Indian Ocean region, and the Taiwan Strait in support missions such as protecting U.S. supply lines, conducting cyber operations (both defensive and offensive), and participating in a blockade against the PRC.54On submarines and other European force deployments, see Max Bergmann and Christopher B Johnstone, “Europe’s Security Role in the Indo-Pacific: Making It Meaningful,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 2024, 6, 13, 16, https://www.csis.org/analysis/europes-security-role-indo-pacific-making-it-meaningful; on protecting U.S. supply lines, see Luis Simon and Zach Cooper, “Rethinking Tradeoffs Between Europe and the Indo-Pacific,” War On the Rocks, May 9, 2023, https://warontherocks.com/2023/05/rethinking-tradeoffs-between-europe-and-the-indo-pacific/; on cyber operations, see Henry Boyd et al., “Taiwan, Cross-Strait Stability and European Security: Implications and Response Options,” International Institute for Strategic Studies, March 2022, 4, https://www.iiss.org/research-paper/2022/03/taiwan-cross-strait-stability-and-european-security/; on participation in a blockade, see Sheryn Lee and Benjamin Schreer, “Will Europe Defend Taiwan,” Washington Quarterly 45, no. 3 (2022): 172–173, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/0163660X.2022.2128565.

In parallel, Western strategists began discussing the steps that NATO could take to assist the United States in domains such as ballistic missile defense, intelligence sharing, and joint planning to enhance its capabilities in maritime Asia.55Mazarr, “Why America Still Needs Europe.” Other experts, including former American officials, advocated for including Hawaii in NATO’s strategic perimeter and for inviting Japan, South Korea, Australia, and other Asian states to join the Western alliance.56On NATO and Hawaii, see John Hemmings and David Santoro, “NATO Needs to Plug the “Hawaii Gap” in “U.S. Indo-Pacific Deterrence Strategy,” Pacific Forum, July 9, 2024, https://pacforum.org/publications/pacnet-47-nato-needs-to-plug-the-hawaii-gap-in-the-us-indo-pacific-deterrence-strategy/; on NATO’s expansion to Indo-Pacific states, James Stavridis, “Forget an ‘Asian NATO’ – Pacific Allies Could Join the Real One,” Bloomberg, April 8, 2024, https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2024-04-08/nato-should-expand-to-japan-australia-south-korea-new-zealand. They also discussed the possibility of an “Asian NATO,” which the Trump I administration had floated in 2020.57On the possibility of an “Asian NATO,” see Michael J. Green, “Never Say Never to an Asian NATO,” Foreign Policy, September 6, 2023, https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/09/06/asian-nato-security-alliance-china-us-quad-aukus-japan-australia-taiwan-military-biden/; on U.S. officials and the possibility of an “Asian NATO,” see Hal Brands, “An Asian NATO? The US Has Better Options for its Allies,” Bloomberg, September 23, 2020, https://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2020-09-23/an-asian-nato-u-s-has-better-options-for-its-allies-and-china.

Yet that approach would be unlikely to deter China or deliver useful military support in the event of a war. Inter-oceanic power projection remains a tremendously demanding endeavor from both a financial and technological perspective, two areas in which European navies have struggled to keep pace in the post-Cold War era.58Pierre Morcos and Colin Wall, “Are European Navies Ready for High-Intensity Warfare?” War on the Rocks, January 31, 2022; https://warontherocks.com/2022/01/are-european-navies-ready-for-high-intensity-warfare/; Roger Hilton, “On the Decline of European Naval Power: A conversation with Jeremy Stöhs, PT. 2,” Center for International Maritime Security, September 11, 2019, https://cimsec.org/on-the-decline-of-european-naval-power-a-conversation-with-jeremy-stohs-pt-2/. Due to their long-standing dependency on the U.S. (and U.S. efforts to maintain that dependency), European states have largely neglected the assets necessary to meaningfully project power overseas over long periods, thereby making any naval deployments in maritime Asia mostly symbolic.59Eva Pejsova, “The EU’s Naval Presence in the Indo-Pacific,” Hague Centre for Strategic Studies, March 2023, 1–8, https://hcss.nl/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/03-Eva-Pejsova-European-naval-role-in-the-Indo-Pacific.pdf.

Moreover, although the aggregate European military budget has significantly increased in recent years (especially since the start of the Ukraine war), national rivalries and military-industrial lobbies have hindered the EU’s military power from growing accordingly.60Hugo Meijer and Stephen G. Brooks, “Illusions of Autonomy: Why Europe Cannot Provide for its Security if the United States Pulls Back,” International Security 45, no. 4 (Spring 2021): 31–32, https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00405. For instance, the bloc’s militaries suffer from substantial redundancies, as illustrated by the existence of 178 major European weapon systems, compared to just 30 for the United States.61Niall McCarthy, “Europe Has Six Times as Many Weapon Systems as the US,” Statista, data cited in Forbes, February 20, 2018, https://www.forbes.com/sites/niallmccarthy/2018/02/19/europe-has-six-times-as-many-weapon-systems-as-the-u-s-infographic/.

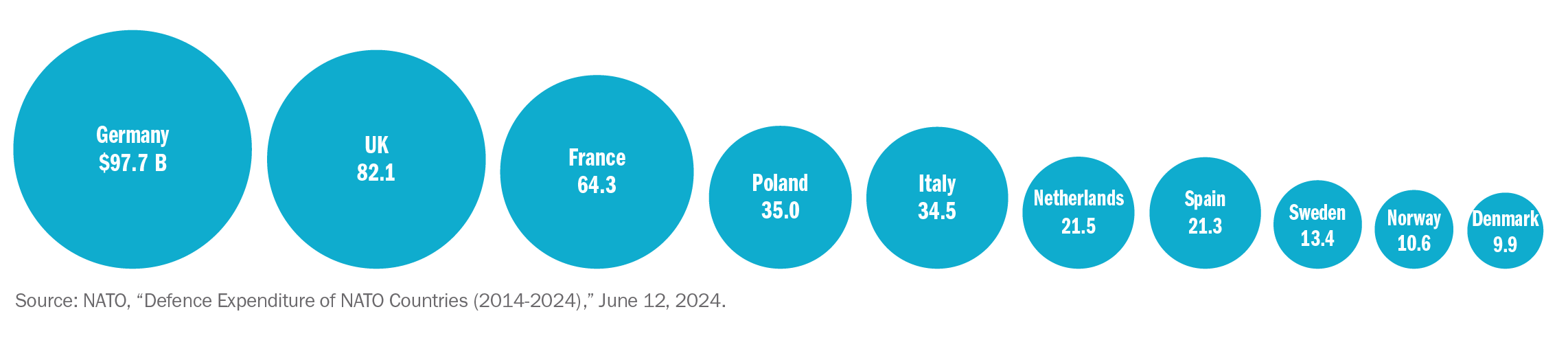

Top 10 NATO-Europe defense spenders (2024 estimates)

Regardless of its military potential, the rationale for reallocating European assets to the Indo-Pacific region is flawed. One problem is the lack of military-industrial complementarities between Europe’s land-based theater and maritime Asia’s sea-and-air-based theater.62Mathieu Droin, Kelly A. Grieco, and Happymon Jacob, “Why NATO Should Stay Out of Asia: The Alliance Would Leave the Region Less, Not More, Secure,” Foreign Affairs, July 8, 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/world/why-nato-should-stay-out-asia. Moreover, expanding NATO’s strategic planning to Asia could exacerbate the significant intra-European differences that already exist regarding threat perceptions, weapon development priorities, and doctrinal orientations. For example, whereas Northern and Eastern European states focus overwhelmingly on Russia, many Southern and Western European nations also closely monitor the migration-terrorism nexus in Africa and the Middle East.63Meijer and Brooks, “Illusions of Autonomy,” 18. In that context, adding the Indo-Pacific to NATO’s agenda would undermine the alliance’s internal cohesion.

Most importantly, expanding NATO’s prerogatives to the Indo-Pacific would incur severe opportunity costs. Given the instability of Europe’s eastern and southern flanks, along with a resurgent great power rivalry in the Arctic, any attempt to project military power toward the Indo-Pacific would make European countries even more vulnerable.64Paul Van Hooft, “China and the Indo-Pacific in the 2022 NATO Strategic Concept,” Atlantisch Perpectief 46, no. 4 (2022), 49, https://www.jstor.org/stable/48732625.

The Ukraine war has only compounded this problem, imposing tremendous costs on the EU’s economic and industrial potential while generating significant political instability.65Molly O’Neal, “The Risks to Germany and Europe of a Prolonged War in Ukraine,” Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, October 7, 2024, https://quincyinst.org/research/the-risks-to-germany-and-europe-of-a-prolonged-war-in-ukraine/. The bloc’s considerable assistance to Kyiv has depleted European military stocks.66Daniel Michaels, “How Europe’s Military Stacks Up Against Russia Without US Support,” Wall Street Journal, March 13, 2025, https://www.wsj.com/world/europe/europe-military-compared-russia-without-us-1ccd751b. Moreover, thanks in large part to support from China, North Korea, and Iran, Russia has demonstrated an unexpected resilience to both battlefield losses and Western sanctions.67Ian Proud, “We Can’t ‘Ban’ Talk of Russian Resilience to Sanctions,” Responsible Statecraft, January 6, 2025, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/are-russian-sanctions-working/. If measured in purchasing power parity, Russia’s 2024 military budget surpassed the combined budgets of its European counterparts.68Lucia Mackenzie, “Russian Defense Spending Overtakes Europe, Study Finds,” Politico, February 12, 2025, https://www.politico.eu/article/russian-defense-spending-overtakes-europe-study-finds/. Admittedly, Russia has not performed well on Ukraine’s battlefields and its capacity to wage war elsewhere in Europe is dubious (assuming Vladimir Putin ever entertained such a goal).69George Beebe, Mark Episkopos, and Anatol Lieven, “Right-Sizing the Russian Threat to Europe,” Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, July 8, 2024, 20–21, https://quincyinst.org/research/right-sizing-the-russian-threat-to-europe/#executive-summary. However, any NATO attempt to refocus on the Indo-Pacific would automatically erode the region’s ability to deter or face future aggressions in whatever shape or form.

This exposure is even more glaring in light of recent developments. Since January 2025, the Trump administration has signaled it wants to disengage from the Ukraine conundrum and scale down the American troop presence in Europe to cut costs and refocus on the Indo-Pacific.70Olga Chyzh et al., “Trump Says He Will End the War in Ukraine – But How, and Who Will Benefit? Our Panel Responds,” Guardian, February 22, 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2025/feb/22/donald-trump-end-war-ukraine-us-europe. Although Washington has failed to halt the fighting between Kyiv and Moscow and signaled its growing frustration with Putin, some regional drawdown appears probable, regardless of the outcome on Ukraine’s battlefields.71On the failure of its talks with Putin, see Andrew Roth and Pjotr Sauer, “Trump Says It May Be Better to Let Ukraine and Russia ‘Fight for a While,’” Guardian, June 5, 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/jun/05/russia-warns-it-will-respond-to-ukraine-drone-attacks-how-and-when-it-sees-fit; on the potential U.S. drawdown, see John R. Deni, “A Drawdown of US Forces in Europe Is All but Certain,” Foreign Policy, April 14, 2025, https://foreignpolicy.com/2025/04/14/us-troops-europe-nato-drawdown-pentagon-trump-hegseth-posture-review/. Yet despite some efforts to step up, European leaders have urged the Trump administration to reconsider and have struggled mightily to assemble the agile and combat-ready military force that would be necessary to deter any future Russian aggression.72Barry R. Posen, “How Europe Can Deter Russia,” Foreign Affairs, April 21, 2025, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/north-america/how-europe-can-deter-russia With this in mind, NATO’s involvement in the Indo-Pacific seems even more ill-advised.73Tim Zadorozhnyy, “Europe Warns that Sudden Troop Reduction May Destabilize NATO’s Defenses, Bloomberg Reports,” Kyiv Independent, April 9, 2025, https://kyivindependent.com/europe-warns-us-uncontrolled-troops-reduction-may-destabilize-natos-defenses-media-reports/.

Problem 3: Perpetuating the EU’s dependency on the U.S.

A growing NATO role in the Indo-Pacific also risks prolonging Europe’s long-standing strategic dependency on the United States. The Ukraine war initially encouraged the region’s leaders to take steps toward strategic autonomy. For example, the “Strategic Compass” that the EU published in March 2022 created a 5,000-strong Rapid Deployment Force, introduced faster decision-making processes, and enabled extra-budgetary tools to enhance the bloc’s military responsiveness.74Sylvia Pfeifer and Henry Foy, “Europe’s Defence Sector: Will War in Ukraine Transform Its Fortunes?” Financial Times, July 18, 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/0a917386-7a62-4e4a-9b89-123933f750a6; Nicole Koenig, “Putin’s War and the Strategic Compass: A Quantum Leap for the EU’s Security and Defense Policy?” Hertie School, Jacques Delors Centre, April 29, 2022, 3, https://www.delorscentre.eu/en/publications/detail/publication/putins-war-and-the-strategic-compass-a-quantum-leap-for-the-eus-security-and-defence-policy. More broadly, according to the alliance, the number of NATO states that spent at least 2 percent of their GDP on defense jumped to 23 by the end of 2024, up from just three in 2014.75“The Secretary-General’s Annual Report 2024,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, April 2025, 16, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2025/4/pdf/sgar24-en.pdf. The aggregated military budget of NATO’s European members plus Canada soared by 20 percent in 2024 to $485 billion.76“Press conference by NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, February 13, 2025, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/opinions_232958.htm.

But those measures did not enhance European strategic autonomy or military capability independent of the United States. The Biden administration used the Ukraine war to reassert America’s status as the cornerstone of European security. After February 2022, Washington increased its troop presence on the ground from 64,000 to 85,000–100,000 (depending on rotations) and deployed many of those troops to Eastern Europe, closer to Russia’s border.77On the U.S. footprint, see Grand, “Defending Europe with Less America,” 6; on the U.S. deployments in Eastern Europe, see A. Wess Mitchell, “Why Western Europe Is Still Falling Short in NATO’s East,” Foreign Affairs, July 5, 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/europe/falling-short-nato-east-deterring-russia. More broadly, America’s massive mobilization in support of Ukraine incentivized European leaders to increase their reliance on U.S. political leadership, strategic planning, and weapon systems.78Sudha David-Wilp, “Why Germany Still Hasn’t Stepped Up,” Foreign Affairs, April 17, 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/germany/germany-still-hasnt-stepped. For instance, the EU’s “Strategic Compass” endeavored to expand Brussels’ partnership with NATO across the board, including in outer space and with new technologies.79Koenig, “Putin’s War and the Strategic Compass,” 6. France, Germany, and Spain’s plan to develop a world-class jet fighter aircraft by 2040 was questioned following Berlin’s sudden decision to procure a new batch of American F-35s.80Peter Hille, “Why Germany is Opting for the US-Made Stealth Fighter Jet,” DW, March 16, 2022, https://www.ifri.org/en/espace-media/lifri-medias/f-35-why-germany-opting-us-made-stealth-fighter-jet.

European military aid sent to Ukraine

The Biden administration took advantage of Europe’s military limitations to increase its access to European Defense Agency projects and to ensure that the EU’s first-ever defense industrial strategy, adopted in March 2024, would be subsumed under the logic of Atlanticism.81On the European Defense Agency, see Max Bergmann and Sophia Besch, “Why European Defense Still Depends on America,” Foreign Affairs, March 7, 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/ukraine/why-european-defense-still-depends-america; on the European defense industrial strategy, see Max Bergmann et al., “The European Union Charts its Own Path for European Rearmament,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, March 8, 2024, https://www.csis.org/analysis/european-union-charts-its-own-path-european-rearmament. Far from representing a new trend, those moves were the latest iteration of a decades-old American opposition to any European policy that could make the region less dependent on the U.S. government and military corporations.82Christopher Layne, The Peace of Illusions: American Grand Strategy from 1940 to the Present (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2006), 115; Desmaele, Europe’s Evolving Role in US Grand Strategy, 74.

This dependency could persist through the Trump II administration. In June 2025, NATO’s members pledged to increase their defense spending to 5 percent of GDP by 2035 (including 1.5 percent for “military adjacent” items like roads and bridges), which secretary-general Rutte described as a “quantum leap.”83Alice Tidey, “Rutte: NATO’s New 5% Target Is ‘Quantum Leap’ to Improve Air Defense and Buy ‘Thousands’ of Tanks,” Euronews, June 23, 2025, https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2025/06/23/rutte-natos-new-5-target-is-quantum-leap-to-improve-air-defence-and-buy-thousands-of-tanks. Yet this plan locks the U.S. in without guaranteeing that an integrated, combat-ready, and independent European military will develop by then.84Moreover, Spain refused to commit to the 5 percent rule. Steven Erlanger and Lara Jakes, “In a Win for Trump, NATO Agrees to a Big Increase in Military Spending,” New York Times, June 25, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/06/25/world/europe/nato-increase-military-spending-trump.html.

European governments, already under heavy fiscal strain and exhausted by the Ukraine war, are unlikely to meet these prohibitively costly targets. Even if they do, they would still need to transcend their national rivalries, modernize their highly unionized military industries, address shortages of military and defense-industrial manpower, shed their long-standing preference for U.S. weapon systems, and make major advancements in miniaturized semiconductors, AI, and other critical technologies.85On Europe’s financial constraints, national limitations, and preference for U.S. military supplies, see Kavanagh and DePetris, “More European Defense Spending Isn’t Cause for Celebration”; on its unionized industries, manpower shortages, and technological limitations, see Stephen Bryen, “NATO’s 5% Defense Pledge Won’t Make the Kremlin Shake in its Boots,” Asia Times, June 26, 2025, https://asiatimes.com/2025/06/nato-5-defense-pledge-wont-make-the-kremlin-shake-in-its-boots/#. Although those objectives are not beyond reach, European leaders may continue to defer to U.S. leadership since Washington has not lowered its troop numbers, relinquished control over NATO’s institutional setup, or seriously contemplated curtailing its lucrative regional defense sales (which the 5 percent rule may take to new heights).86On the U.S. footprint and institutional control, see Kavanagh and DePetris, “More European Defense Spending Isn’t Cause for Celebration”; on U.S. defense corporations and the European market, see “NATO’s 5% Defense Pledge Could Unlock $2.7T for U.S. Contractors, BTIG Says,” MSN, July 2, 2025, https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/world/nato-s-5-defense-pledge-could-unlock-2-7t-for-u-s-contractors-btig-says/ar-AA1HPRqo.

Requesting NATO take on more responsibilities in the Indo-Pacific would perpetuate this deep-seated dependency, further limiting the EU’s ability to invest in its own security (and do so collectively) and increasing European leaders’ desire to keep Washington as heavily involved as possible.87Max Bergmann, “NATO Missed a Chance to Transform Itself,” War on the Rocks, August 7, 2024, https://warontherocks.com/2024/08/nato-missed-a-chance-to-transform-itself/. American involvement, being a known quantity, remains more appealing to politicians than the sacrifices, compromises, and uncertainties that a genuine effort towards European strategic autonomy would necessitate.88Stephen M. Walt, “Why Europe Can’t Get Its Military Act Together,” Foreign Policy, February 21, 2024. https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/02/21/europe-military-trump-nato-eu-autonomy/.

The risk of path dependency also exists on the other side of the Atlantic. An expansion of NATO’s involvement in Asia could incline U.S. leaders to cling to the illusory belief that they can sustain their hegemony in both Europe and the Indo-Pacific by “growing the connective tissue” that unites Washington’s “democratic allies and partners” in those two regions in the domains of “technology, trade, and security.”89Droin, Grieco, and Jacob, “Why NATO Should Stay Out of Asia.”

Problem 4: Exacerbating tensions with China

NATO’s activities in the Indo-Pacific could also harm the West’s relationship with Beijing, undermining beneficial trade and potentially even leading to conflict. NATO and China have a long history of mistrust going back to the PRC’s founding in October 1949. Tensions were only exacerbated after the intervention of several Western European states in the Korean War and the participation of NATO allies in the embargo that followed.90On the Korean War, see Michael Yahuda, “The Sino-European Encounter: Historical Influences on Contemporary Relations,” in David Shambaugh, Eberhard Sandschneider, and Zhou Hong, China-Europe Relations: Perceptions, Policies and Prospects (New York: Routledge, 2007), 23; on the embargo, see Yongjin Zhang, China in International Society Since 1949: Alienation and Beyond (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998), 23.

Despite some cooperation and consultation against the Soviet Union after the early 1970s and against terrorism after 9/11, Chinese leaders tend to perceive NATO as designed to further America’s encirclement of the PRC and worry about the alliance’s post-Cold War expansion in continental Eurasia.91On the fluctuations of China’s relationship with NATO over time, see Philip Shetler-Jones, “Sewage of the Cold War: China’s Expanding Narratives on NATO,” U.S. Institute of Peace, November 21, 2013, 4, https://www.usip.org/publications/2023/11/sewage-cold-war-chinas-expanding-narratives-nato; on China’s concerns about NATO’s expansion, see John Garver, China’s Quest: The History of the Foreign Relations of the People’s Republic of China (London: Oxford University Press, 2015), 545; Aaron Friedberg, Getting China Wrong (Medford, Mass.: Polity Press, 2022), 127. They fear alliance military interventions without UN Security Council approval, remembering when U.S. B-2 bombers partly destroyed the Chinese embassy in Belgrade by accident in 1999 (Beijing considered this deliberate), which led them to worry about potential hostile operations near Taiwan, Xinjiang, or Tibet.92Avery Goldstein, Rising to the Challenge: China’s Grand Strategy and International Security (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005), 126–127; M. Taylor Fravel, Active Defense: China’s Military Strategy Since 1949 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019), 222–223; Warren Cohen, America’s Response to China: A History of Sino-American Relations (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019), 266. They also resent the increasingly close strategic partnerships that NATO has nurtured with Japan, South Korea, Australia, India, Mongolia, and other Chinese neighbors in the twenty-first century.93Luis Simón, “Europe, the Rise of Asia, and the Future of the Transatlantic Relationship,” 986–987; Ian Brzezinski, “NATO’s Role in a Transatlantic Strategy on China,” Atlantic Council, June 1, 2020, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/natos-role-in-a-transatlantic-strategy-on-china/.

In recent years, Beijing has made it increasingly clear that it views the prospect of greater European involvement in its immediate vicinity as a hostile move dictated by the United States. For example, in March 2022, Chinese leaders warned that, “if allowed to go on unchecked,” NATO’s local ambitions would “push the Asia-Pacific over the edge of an abyss.”94Simone McCarthy, “What China Really Means When It Talks about NATO’s Eastward Expansion,” CNN, March 23, 2022, https://edition.cnn.com/2022/03/23/china/china-ukraine-warning-us-asia-analysis-intl-hnk/index.html Three months later, they condemned how the alliance had “flexed its muscle” and “sought to stir up bloc confrontation” in the region.95Shetler-Jones, “Sewage of the Cold War: China’s Expanding Narratives on NATO,” 10. In March 2023, Xi Jinping himself went one step further by accusing “Western countries—led by the U.S.” of implementing “all-round containment, encirclement and suppression against [China].”96Cited in Noah Barkin and Andrew Small, “Congressional Testimony: Aligning Transatlantic Approaches on China,” German Marshall Fund, June 7, 2023, https://www.gmfus.org/news/congressional-testimony-aligning-transatlantic-approaches-china.

To be sure, the PRC’s fierce rhetoric against the West stems partly from domestic political calculations and a desire to reach out to Russia and the Global South.97Paul Haenle and Sam Bresnick, “China’s Ukraine Calculus Is Coming into Focus,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, April 4, 2022, https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2022/04/chinas-ukraine-calculus-is-coming-into-focus?lang=en. Chinese leaders understand that Europe is peripheral to their immediate security concerns and that the Biden administration’s pressures played a significant role in the European turn against China.98Joel Wuthnow and Elliot S. Ji, “Bolder Gambits, Same Challenges: Chinese Strategists Assess the Biden Admin’s Indo-Pacific Strategy,” China Leadership Monitor, August 29, 2023, 2, https://www.prcleader.org/post/bolder-gambits-same-challenges-chinese-strategists-assess-the-biden-admin-s-indo-pacific-strategy. Still, they resent Europe’s mobilization against the “Sino-Russian” axis, increasingly stringent restrictions against Chinese companies, and growing (if reluctant) endorsement of Washington’s trade and tech war against the PRC, which includes drastic sanctions in the vital domain of chip-making equipment.99Michelle Toh, “The US-China Chip War Is Spilling Over to Europe,” CNN, November 25, 2022, https://edition.cnn.com/2022/11/25/tech/us-china-chip-war-spillover-europe-intl-hnk/index.html.

NATO’s involvement in the Indo-Pacific could cause severe disruptions. The possibility of punitive Chinese economic measures is real. Although the PRC has employed conventional economic coercion for a long time, the Trump and Biden administrations’ growing pressures on and sanctions against China and Russia have prompted Beijing to develop new legal and regulatory instruments to inflict potentially debilitating costs on states and companies that threaten its interests, including export controls and “property and asset seizures.”100Evan S. Medeiros and Andrew Polk, “China’s New Economic Weapons,” Washington Quarterly 48, issue 1 (2025): 99–100, 110, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0163660X.2025.2480513.

As suggested by its defiant response to threatened American tariffs in early 2025, China holds significantly greater economic leverage than in the recent past. It has reduced its dependency on Western markets, become a key supplier of critical minerals, and made breakthroughs in AI, green technology, and other high-value sectors.101Koh Ewe, “Five Cards China Holds in a Trade War with the US,” BBC, April 23, 2025, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c0kxe1m1y26o. Although the PRC remains vulnerable in many respects, a full-fledged Sino-Western economic war would surely cripple Western nations—and the rest of the world.102Jim Pollard, “Trade Wars Would Be ‘Catastrophic’ for the World Economy: WTO,” Asia Financial, January 23, 2025, https://www.asiafinancial.com/trade-wars-would-be-catastrophic-for-world-economy-wto.

The risk of a military conflagration cannot be dismissed either. The rise of China’s capabilities and assertiveness has caused or contributed to multiple diplomatic crises near the Taiwan Strait, the South China Sea, the Senkaku Islands, and other Indo-Pacific flashpoints.103Li Beiping, “Experts See Rival Military Exercises as Sign of Increasing Conflict Risks in Indo-Pacific,” Voice of America, July 19, 2024, https://www.voanews.com/a/experts-see-rival-military-exercises-as-sign-of-increasing-conflict-risks-in-indo-pacific-/7705867.html. Sino-Western economic tensions could lead to armed conflict.104Jake Werner, “US-China Trade War: Could It Turn Violent, and When?” Responsible Statecraft, April 9, 2025, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/china-tariffs/. Regardless of the military outcome, such a conflict would have catastrophic consequences for all, not to mention the possibility of a nuclear escalation.105Doug Bandow, “What Would a US War with China Look Like,” Cato Institute, October 24, 2022, https://www.cato.org/commentary/what-would-us-war-china-look.

Problem 5: Deepening China’s partnership with Russia

NATO’s deeper involvement in Asia could also incentivize China to strengthen its partnership with Russia. The Sino-Russian partnership has deepened significantly since the onset of the Ukraine war.106Elizabeth Wishnick, “The Sino-Russian Partnership: Cooperation without Coordination,” China Leadership Monitor, February 26, 2025, 1–9, https://www.prcleader.org/post/the-sino-russian-partnership-cooperation-without-coordination. Some experts, including in the Trump II administration, have entertained a potential “reverse Kissinger” where the U.S. persuades the Kremlin to collaborate against the PRC (as Washington did with Beijing against the Soviet Union in the 1970s and 1980s).107David Ignatius, “Trump Bets on a ‘Reverse Kissinger,’” Washington Post, April 3, 2025, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2025/04/03/trump-foreign-policy-reverse-kissinger-china-russia-gamble/; Asawin Suebsaeng, “Henry Kissinger Pushed Trump to Work with Russia to Box in China,” Daily Beast, July 25, 2018, https://www.thedailybeast.com/henry-kissinger-pushed-trump-to-work-with-russia-to-box-in-china/. According to that logic, Washington could exploit the two countries’ historical rivalry, their persistent competition in neighboring regions such as Central Asia and the Arctic, and Moscow’s discomfort with China’s rising power to its advantage.108Philipp Ivanov, “Together and Apart: The Conundrum of the China-Russia Partnership,” Asia Society, October 11, 2023, https://asiasociety.org/policy-institute/together-and-apart-conundrum-china-russia-partnership#what-divides-russia-and-china–16732.

Yet the Sino-Russian partnership is rooted in a deep fear and resentment of U.S. hegemony. It’s also based on significant economic complementarities, similar authoritarian outlooks, and a strong personal bond between Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin. Moreover, although the Ukraine war has called into question the stability of Putin’s rule, regime change would be unlikely to prompt Moscow to alter its anti-Western strategic orientation.109Max Bergmann, “What Could Come Next? Assessing the Putin Regime’s Stability and Western Policy Options,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, January 20, 2023, 10–11, https://www.csis.org/analysis/what-could-come-next-assessing-putin-regimes-stability-and-western-policy-options Therefore, a growing NATO involvement in the Indo-Pacific would only further consolidate the Sino-Russian partnership.

This process could further compromise Europe’s stability. Beijing’s assistance has been vital to Russia since February 2022, from providing Putin’s regime with a much-needed market outlet to supplying most of the dual-use technologies required by the Russian army—at tremendous cost to the European continent.110On the importance of Beijing’s assistance, see Henry Foy et al., “Janet Yellen Warns China of ‘Significant Consequences’ If Its Companies Support Russia’s War,” Financial Times, April 5, 2024, https://www.ft.com/content/ba524406-ee6c-4c39-9ac2-110a2549569a; on Beijing’s economic and technological support, see Renaud Foucart, “China Has the Power to End the Ukraine War,” Asia Times, July 3, 2024, https://asiatimes.com/2024/07/china-has-the-power-to-end-the-ukraine-war/. Should those strategic ties deepen, it could lead Putin to prolong his campaign or resume it at a later time, especially if China agrees.111Andrew Scobell, “China and Ukraine: Pulling Its Weight with Russia or Potemkin Peacemaker,” U.S. Institute of Peace, November 2024, https://www.usip.org/publications/2024/11/china-and-ukraine-pulling-its-weight-russia-or-potemkin-peacemaker. It could also result in new attempts to destabilize Europe through cyber-attacks, political influence activities, and other means.112Natalie Sabanadze, Abigaël Vasselier, and Gunnar Wiegand, “China-Russia Alignment: A Threat to Europe’s Security,” Mercator Institute for China Studies, June 26, 2024, 11–12, https://merics.org/en/report/china-russia-alignment-threat-europes-security

The consequences could be just as far-reaching in the Indo-Pacific. For instance, China could access new Russian military technologies. Moscow’s exports have already enhanced the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), as seen with its SU-35 fighter aircraft and S-400 anti-air missiles, which bolstered Beijing’s defenses and the range of its air force.113Richard Weitz, The New China-Russia Alignment: Critical Challenges to US Security (Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 2022), 117. But Russia has other assets that could help shift the regional balance of power, including submarine technologies that would significantly enhance the stealth of Chinese submarines (which currently lag far behind the U.S. in this critical domain).114Some reports suggest Moscow recently started to share those technologies. Keith Johnson, “The Very Real Limits of the Russia-China ‘No Limits’ Partnership, Foreign Policy, April 30, 2024, https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/04/30/russia-china-partnership-trade-relations/; Thibaut Spirlet, “Russia could give China submarine tech that would cut into US undersea dominance, US admiral says,” Yahoo News, November 25, 2024, https://www.yahoo.com/news/russia-could-china-submarine-tech-130839783.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

The risk of Sino-Russian wartime collaboration would also increase. Among other contributions, the Kremlin could provide “a strategic rear” to China, interfere with U.S. surveillance capabilities, or augment the PRC’s military-industrial potential.115On Russia offering a “strategic rear,” see Oriana Skylar Mastro, “Sino-Russian Military Alignment and Its Implications for Global Security,” Security Studies 33, issue 2 (2024): 268–269, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09636412.2024.2319587; on Russia’s interference with U.S. surveillance capabilities, see Andrea Kendall-Taylor and Nicholas Lokker, “Russia-China Defense Cooperation,” Center for a New American Security, April 2023, 7–8, https://s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/files.cnas.org/documents/edited-TSP_Russia-China-report_FINAL2.pdf; on Russia’s industrial-military support, see Mastro, “Sino-Russian Military Alignment,” 289. Beijing and Moscow could also coordinate (possibly with Iran and North Korea) to destabilize the Korean Peninsula, the Strait of Hormuz, Europe’s neighborhoods, or other areas, thereby reducing the United States’ capacity to focus on countering China in the Indo-Pacific.116Stephen Wertheim, “The United States Stepping Back from Europe is a Matter of When, Not Whether,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, April 1, 2024, https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2024/04/the-united-states-stepping-back-from-europe-is-a-matter-of-when-not-whether?lang=en; Dongchan Kim, “The Biden Doctrine and China’s Response,” International Area Studies Review 26, issue 2 (2022): 117, https://doi.org/10.1177/22338659221135838.

Problem 6: Losing support in the Global South

A growing NATO push in the Indo-Pacific could also degrade the alliance’s image in the Global South. Although many countries have soured on China’s economic dominance and abuses in recent years, the PRC retains significant appeal in Africa, Latin America, Asia, and other developing regions, with some surveys ranking it ahead of the United States in terms of popular opinion.117Roberto S. Foa et al., “A World Divided: Russia, China, and the West,” Bennett Institute for Public Policy, October 20, 2022, 2, https://www.bennettinstitute.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/A_World_Divided.pdf.

Meanwhile, the Biden administration’s attempts to frame its grand strategy around the “democracy vs. autocracy” narrative and the so-called “rules-based international order” have revived the resentment that the West’s military interventionism, devastating sanctions, constant political interference, and troubling double standards have left in many parts of the Global South.118On President Biden’s lofty rhetoric, see “Biden Departs Europe with Message for Putin: West Is More United Than Ever,” The Economist, March 26, 2022, https://www.newsweek.com/biden-departs-europe-message-putin-west-more-united-ever-1692174; on frustrations in the Global South, see Edward Luce, “The West Is Rash to Assume the World is On Its Side Over Ukraine,” Financial Times, March 24, 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/d7baedc7-c3b2-4fa4-b8fc-6a634bea7f4d. This rejection largely explains why Brazil, India, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, and many other countries have refused to embrace the West’s narrative against Russia and China in the Ukraine war, and why Moscow and Beijing’s attempts to portray NATO as warmongering found traction in some parts of the world.119Lukas Fiala, “How the Global South Became Central to China’s Narrative Strategy on Russia’s War in Ukraine,” China Global South Project, March 15, 2025, https://chinaglobalsouth.com/analysis/how-the-global-south-became-central-to-chinas-narrative-strategy-on-russias-war-in-ukraine-2/; Kwan Wei Kevin Tan, “China’s Defense Ministry Rips NATO and Says it’s ‘Like a Walking War Machine,’” Yahoo News, January 26, 2024, https://www.yahoo.com/news/chinas-defense-ministry-rips-nato-083758781.html.

Although they may appear distant at first glance, these trends could prove detrimental to the United States. For all its missteps, the PRC has deftly utilized the controversies generated by the West in the Global South to consolidate its foreign port presence; maximize access to foreign strategic minerals; contest established norms, technical rules, and technological standards in key international organizations; and promote global initiatives that present China as a force for good and the U.S. as a declining and illegitimate leader—among many other gains.120On China’s global port presence and its security implications, see Isaac B. Khardon and Wendy Leutert, “Pier Competitor: China’s Power Position in Global Ports,” International Security 46, issue 4 (2022): 9–47; https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00433; on China’s access to strategic minerals, see Jevans Nyabiage, “China Still Leads the Pack in Africa’s Critical Minerals Race as U.S. Struggles to Keep Up,” South China Morning Post, March 12, 2025, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3301506/china-still-leads-pack-africas-critical-minerals-race-us-struggles-keep; on China’s influence in international organizations, see Hoang Thi Ha and Tham Thi Phuong Thao, “Re-Ordering the World: China’s Global South Focus versus the Ally-Centric Approach of the US,” Fulcrum, November 28, 2024, https://fulcrum.sg/re-ordering-the-world-chinas-global-south-focus-versus-the-ally-centric-approach-of-the-us/; on China’s attempts to de-legitimize Washington’s leadership, see M. Taylor Fravel, “China’s Global Security Initiative at Two: A Journey, Not a Destination,” China Leadership Monitor, June 2024, 9, https://www.prcleader.org/post/china-s-global-security-initiative-at-two-a-journey-not-a-destination. These benefits could help Chinese leaders mitigate some of their vulnerabilities (i.e., energy and food security), augment their capacity to inflict economic pain, and divert Washington’s focus and resources, thereby reducing its ability to hold the line in maritime Asia.121James Holmes, “China Could build an ‘Island Chain’ Around America,” National Interest, March 1, 2025, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/china-could-build-an-island-chain-around-america.

This problem is even more acute in the Indo-Pacific, where many Global South nations have been skeptical, if not openly hostile, to the prospect of a growing NATO presence. For instance, echoing China’s rhetoric, the then-prime minister of Singapore emphasized in May 2022 that an arrangement where “one bloc confronts another… has not been the history in Asia.” Likewise, commenting on the (then-likely) future opening of a NATO office in Japan in June 2023, a senior Indonesian diplomat wrote that the Western alliance’s involvement in the Indo-Pacific would “do more harm than good.”122Bergmann and Johnstone, “Europe’s Security Role in the Indo-Pacific,” 8. Despite being the object of ardent U.S. courtship, Indian leaders have repeatedly stressed that the “NATO template does not apply” to their country.123E.D. Mathew, “NATO’s Growing Shadow over the Asia-Pacific,” New Indian Express, June 21, 2023, https://www.newindianexpress.com/opinions/2023/Jun/21/natos-growing-shadow-over-the-asia-pacific-2587261.html.

To be sure, China’s rise continues to generate intense concerns throughout the Indo-Pacific. But NATO’s growing profile would also increase tensions, helping Beijing expand its economic reach and develop closer security relations with some of the region’s states while eroding America’s ability to do just that.124Hailey Wong, “China’s Military In ‘Competition for Partnerships’ with US in Southeast Asia,” South China Morning Post, September 29, 2024, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/military/article/3280378/chinas-military-competition-partnerships-us-southeast-asia.

A more restrained NATO, a more effective U.S.

Washington’s push to increase NATO’s profile in the Indo-Pacific is flawed and dangerous. A European pivot to Asia will not help much from a military perspective. Among other issues, it will exacerbate tensions with China, encourage further Russo-Chinese military cooperation, and distract European leaders from much-needed efforts to consolidate their own security.

The United States should refrain from transforming NATO into a full-fledged anti-China instrument and from extending the alliance’s strategic perimeter into the Indo-Pacific. Instead, it should acknowledge Russia’s resilience and inability to conquer Europe, and Europe’s significant military potential. It should then scale down its involvement in European security.

A steady reduction of America’s involvement in the region would force the Europeans to address their dependency on Washington full-heartedly. It would incentivize them to focus on the real and urgent problems they face in their immediate eastern neighborhood instead of wasting precious resources to go after China halfway across the world in the hope of keeping the U.S. heavily engaged in Europe.

As they make this necessary adjustment, transatlantic consultations and technical support would enable the U.S. to assist its allies in addressing the logistical, political, and financial bottlenecks that hinder the development of meaningful European combat capabilities. Washington could also encourage NATO to strengthen its communication channels and create new confidence-building mechanisms with the PRC to limit the risk of Sino-Western conflict.

Although it departs from America’s traditional self-conception as the “indispensable nation” and may strain the transatlantic relationship, this approach would enable the U.S. to reorient its focus toward the Indo-Pacific and limit the Sino-Russian strategic partnership. Washington should likewise work to free its grand strategy from the ideological and political delusions of the past. A more realistic and restrained NATO can mean a more focused and effective United States.

Endnotes

- 1Lisa Ferdinando, “Mattis Highlights US Commitment to NATO, Warns of ‘Arc of Insecurity,’” DOD News, February 15, 2017, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/1084785/mattis-highlights-us-commitment-to-nato-warns-of-arc-of-insecurity/.

- 2“National Security Strategy of the United States of America,” White House, December 2017, 2, 25, 27, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905.pdf.

- 3Luis Simón, Linde Desmaele, and Jordan Becker, “Europe as a Secondary Theater? Competition with China and the Future of America’s European Strategy,” Strategic Studies Quarterly, vol. 15, issue 1 (Spring 2021): 94, https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/SSQ/documents/Volume-15_Issue-1/Simon.pdf.

- 4Elsa B. Kania, “Securing Our 5G Future: The Competitive Challenge and Considerations for US Policy,” Center for a New American Security, November 7, 2019, 13, 20–21, https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/securing-our-5g-future; Adam Segal, “Huawei, 5G, and Weaponized Interdependence,” in eds. Daniel W. Drezner, Henry Farrell, and Abraham L. Newman, The Uses and Abuses of Weaponized Interdependence (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2021), 154.

- 5Jengs Ringsmose and Stenn Rynning, “China Brought NATO Closer Together,” War on the Rocks, February 5, 2020, https://warontherocks.com/2020/02/china-brought-nato-closer-together/; David Hutt, “Huawei Losing its 5G Grip on Europe,” Asia Times, July 17, 2020, https://asiatimes.com/2020/07/huawei-losing-its-5g-grip-on-europe/.

- 6Lotje Boswinkel et al., “Alliance Networking in Europe and the Indo-Pacific,” War on the Rocks, December 17, 2024, https://warontherocks.com/2024/12/alliance-networking-in-europe-and-the-indo-pacific/.

- 7“Brussels Summit Communiqué,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, June 14, 2021, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_185000.htm.

- 8“Joint Statement of the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China on the International Relations Entering a New Era and the Global Sustainable Development,” President of Russia, February 4, 2022, http://en.kremlin.ru/supplement/5770#sel=1:21:S5F,1:37:3jE.

- 9Edward Luce, “The World According to NATO,” Financial Times, December 2, 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/72445197-ea9b-43df-bc3a-e0b06832695a; “National Security Strategy,” White House, October 2022, 17, https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Biden-Harris-Administrations-National-Security-Strategy-10.2022.pdf.

- 10Jack Detsch, “Biden Enlists Asian Partners for Unprecedented Russia sanctions Plans,” Foreign Policy, February 22, 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/02/22/biden-russia-ukraine-sanctions-asia-allies-export-controls-invasion-plans/.

- 11“NATO 2030: United for a New Era,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, November 25, 2020, 47, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2020/12/pdf/201201-Reflection-Group-Final-Report-Uni.pdf.

- 12Marianne Schneider-Petsinger et al., “Transatlantic Cooperation on the Indo-Pacific: European and US Priorities, Partners, and Platforms,” Chatham House, November 2022, 2–5, https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/2022-11/2022-11-17-transatlantic-cooperation-indo-pacific-schneider-petsinger-et-al.pdf.

- 13On European arms sales, see Luis Simón, “Europe, the Rise of Asia and the Future of the Transatlantic Relationship,” International Affairs, vol. 91, issue 5 (September 2015): 986, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24539014; on European naval deployments, see Jan Gerber, “NATO Should Defend Europe, Not Pivot to Asia,” Defense Priorities, February 18, 2022, 3, https://www.defensepriorities.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/DEFP_NATO_should_defend_Europe_not_pivot_to_Asia.pdf.

- 14Gerber, “NATO Should Defend Europe,” 1–3.

- 15“NATO 2022 Strategic Concept,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, June 29, 2022, 11, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2022/6/pdf/290622-strategic-concept.pdf.

- 16Henry Foy and Demetri Sevastopulo, “NATO Holds First Dedicated Talks on China Threat to Taiwan,” Financial Times, November 30, 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/d7fa2d2b-53be-4175-bf2b-92af5defa622.

- 17Hae-Won Jun, “NATO and its Indo-Pacific Partners Choose Practice Over Rhetoric,” RUSI, December 5, 2023, https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/nato-and-its-indo-pacific-partners-choose-practice-over-rhetoric-2023.