October 3, 2025

Grand strategy: Deterrence

This explainer is part of the series "Grand Strategy Explained"

Key points

- Deterrence is the mobilization of coercive means to convince an adversary not to take an aggressive action. This can mean mobilizing an effective defense—convincing an adversary they will not be able to achieve their goal—or threatening to punish an adversary so even successful aggression doesn’t seem worthwhile.

- The ability to deter an adversary requires that they perceive both the capability and the will to carry out a deterrent threat—in other words, that they find the deterrent threat “credible.” It also requires an implicit assurance that the adversary will not suffer should they refrain from taking action.

- The massive and mutually destructive power of nuclear weapons makes leaders especially cautious about taking actions that could escalate to nuclear war, thereby suppressing the incentives for conventional war between nuclear-armed states.

- Extended nuclear deterrence, such as the “nuclear umbrella” the United States has extended to many of its allies since World War II, puts strain on the credibility underlying nuclear deterrence since it risks annihilation on behalf of allies. Extended deterrence becomes less credible and therefore more likely to fail when the fate of the third party is not vital to the state defending it.

- Now that its core allies have the latent capability to defend themselves—including with nuclear weapons—the United States should exit unnecessary commitments to extended deterrence.

Since the end of World War II, the great powers have not directly fought one another, largely due to their ability to deter one another with the devastating threat of nuclear weapons. This paper reviews basic concepts of deterrence, particularly nuclear and extended deterrence, and the role of “credibility” in maintaining peace. It will then review the United States’ current commitments to provide deterrence on behalf of its allies and argue that these commitments exceed the United States’ capabilities and interests. To deter threats against the interests it values most, the United States should downsize its present commitments and rigorously prioritize its goals.

Deterrence in general: Definitions and concepts

Deterrence, in its international political and military sense, is the mobilization of coercive means held in reserve to shape an adversary’s cost-benefit calculus and thereby convince them not to take some undesirable action.1John J. Mearsheimer, Conventional Deterrence (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1983), 14. Deterrence therefore hinges primarily on the perception held by an adversary that one has both the capabilities and the will to act if transgressed against. Deterrence is distinct from “compellence” in that it seeks to prevent an unwanted action by another, whereas compellence threatens to force another to take some action.2Thomas C. Schelling, Arms and Influence (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 69–91. While both are meant to shape an adversary’s behavior, deterrence essentially seeks to maintain the status quo, whereas compellence seeks to change the status quo.

Deterrence is in some ways paradoxical. Its logic is reflected in the Reagan-era slogan “peace through strength,” or the older Roman maxim “if you want peace, prepare for war.” This insight, though accurate in itself, can be misleading or incomplete, as discussed below. Deterrence proceeds from the fact that in the anarchical realm of international politics, the intentions of other states remain opaque, and security ultimately relies on power. Since survival is the sine qua non for a state, states that survive are “socialized by the system,” in Kenneth Waltz’s words, to value security—and therefore a requisite amount of military power—above other goals.3Kenneth N. Waltz, Theory of International Politics (Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, 1979), 74–77; Kenneth N. Waltz, “Reflections on Theory of International Politics: A Response to My Critics,” in Neorealism and Its Discontents, ed. Robert O. Keohane (New York: Columbia University Press, 1986), 331–337, 341–344. The most reliable guarantor in a “self-help world” is therefore the power a state can bring to bear for its own defense.

There are two main types of deterrence: denial and punishment. Deterrence by denial attempts to convince the adversary that they cannot achieve their objective, or that the goal of their efforts will be denied. This means demonstrating the ability and will to fight in order to defeat the adversary should they attempt to achieve their goal through force—in other words, to stage a successful defense.4Michael J. Mazarr, Understanding Deterrence (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2018), 2–3. By contrast, deterrence via punishment attempts to convince an adversary that whatever benefits they may achieve by taking some action will be outweighed by the costs that will be imposed upon them in response—such as sanctions or retaliatory airstrikes. In conventional terms, punishment accepts that while one may not be able to directly prevent the adversary from achieving their goal, a response can be brought to bear that will be costly—or painful—enough to either result in a net loss for the adversary or persuade them to pursue other options.5Mazarr, Understanding Deterrence, 2–3.

Complications: Assurance and escalation

Deterrence, however, is not as straightforward as the “peace through strength” slogan might suggest. So-called foreign policy “hawks” often promote a single-minded emphasis on maximizing power, demonstrating resolve, and making threats and demands on adversaries. Yet hawks tend to forget that deterrence depends not just on capabilities and resolve, but on what Thomas Schelling referred to as “assurance,” which makes one’s own reaction conditional upon the action of the other.6Schelling, Arms and Influence, 74–75. As Schelling put it, “To say, ‘One more step and I’ll shoot,’ can be a deterrent threat only if accompanied by the implicit assurance, ‘And if you stop I won’t.’ Giving notice of unconditional intent to shoot gives him no choice . . .”7Schelling, Arms and Influence, 74. In other words, if a threat against an adversary is unconditional, they have no reason to comply with a demand and may find themselves even more vulnerable if they do. Without an implicit assurance, therefore, threats against an adversary are likely to make them even more intransigent and may make them feel more compelled to take the very action you had hoped to deter.

There is, of course, a risk that the other state will not find a threat credible, either regarding the threat as a bluff—as in the movie villain’s classic response, “you don’t have the guts”—or perceiving a lack of ability to carry out the threat, e.g., “you can’t shoot straight.” In international politics, this may lead to “deterrence failure,” which in turn may result in the outbreak of war—for example, the failure of Britain and France to deter Nazi Germany from invading Poland. This ability to demonstrate capability and resolve is the bread and butter of deterrence and what hawks typically focus on. On the other hand, if the other state believes they’ll be shot regardless, they may feel they have no choice but make a desperate grab for the gun by attempting to gain some element of surprise.

Deterrence is also complicated by its role in a phenomenon known as the “security dilemma” that can trigger arms racing and an escalatory spiral into conflict between states with otherwise defensive intentions.8John H. Herz, “Idealist Internationalism and the Security Dilemma,” World Politics 2, no. 2 (January 1950): 157–180; Robert Jervis, Perception and Misperception in International Politics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976), 58–113; Robert Jervis, “Cooperation Under the Security Dilemma,” World Politics 30, no. 2 (January 1978): 167–214. Military power is a state’s only reliable insurance policy against the risk of foreign aggression, yet efforts to bolster one’s own defenses may appear to another, equally security-seeking state to be preparations for aggression against them. Counter-efforts they take to deter this perceived threat may, in turn, be perceived as a confirmation of their aggressive intentions, compelling further defensive efforts, etc. Not only does this escalation dynamic undo the relative security each state seeks by arming, but it also increases the risk of conflict between states which both independently wish to avoid it. States become increasingly distrustful, crises become more likely and difficult to diffuse, while each state’s forces may be put on a proverbial “hair trigger,” making the risk of inadvertent escalation more acute.

As Robert Jervis noted, the “deterrence model” helps explain why World War II failed to be averted, while the “spiral model” helps explain why World War I failed to be averted.9Jervis, Perception and Misperception, 94–96. Whereas the former stresses the avoidable risk of impotence and appeasement in the case of a malevolent aggressor, the latter emphasizes the tragic risk of self-fulfilling prophecies and escalation in the case of an otherwise security-seeking peer. Since another’s intentions can never be known with certainty, the “security dilemma” is a “dilemma” in the truest sense. Neither risk can be entirely avoided, only managed and mitigated.10Jervis, Perception and Misperception, 82; Jervis, “Cooperation Under the Security Dilemma.”

Nuclear and extended deterrence

Most states engage in direct deterrence, which is to say, efforts to deter attacks on their own territory, population, and sovereignty. Some states may also commit to the defense of certain strategic interests beyond their borders or immediate periphery that they judge to be vital to their power position and therefore their ability to defend their homeland. This is known as “extended” deterrence.

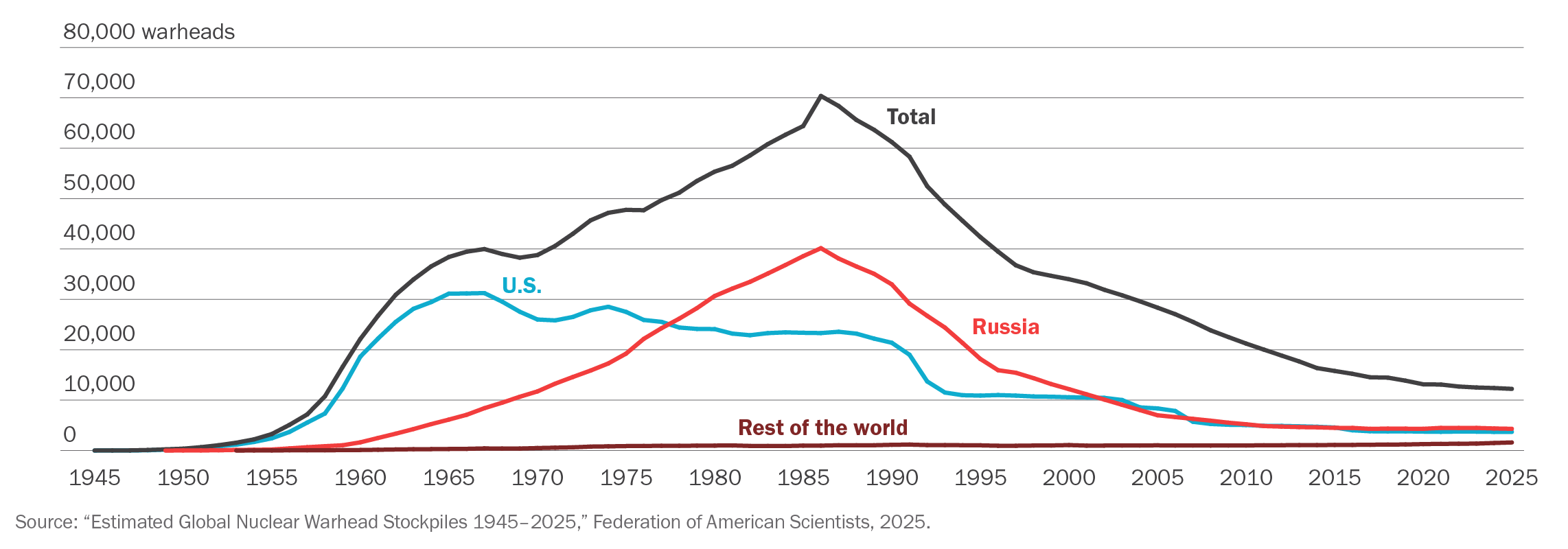

Estimated nuclear warhead stockpiles over time

By far the most “extended” examples of extended deterrence—both in time and space—have been the alliances created by the United States since the end of World War II. In the immediate aftermath of the war, the United States and the Soviet Union were left as the only great powers in the world, with the other major powers of Western Europe and Japan having been ravaged. Despite having been uneasy allies against the Axis Powers, the U.S. and USSR now found themselves as rivals occupying contending spheres of influence in Western Europe and East Asia, struggling to gain incremental advantages at each other’s expense without descending into a new world war.

The United States committed itself to defending and reconstructing the core of Western Europe and Japan, maintaining a sizable troop presence in both regions and investing heavily in their reindustrialization. George Kennan, the intellectual architect of “containment,” saw this as a temporary measure to restore the balance of power—though it fairly quickly evolved into the consolidation and expansion of a permanent U.S. sphere of influence along the rimland of Eurasia.11For Kennan’s thought, see John Lewis Gaddis, Strategies of Containment: A Critical Appraisal of American National Security Policy During the Cold War, rev. and expanded ed. (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2005), 24–86. For the importance of the Eurasian rimland in U.S. strategy, see Nicholas J. Spykman, The Geography of the Peace, ed. Helen R. Nicholl (New York: Harcourt, Brace, and Company, 1944). For the expansion of U.S. grand strategy into “extraregional hegemony,” see Christopher Layne, The Peace of Illusions: American Grand Strategy from 1940 to the Present (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2006), 39–117. Similarly, the Soviet Union dominated Eastern Europe and exerted influence over emerging states in Asia like China and North Korea as well as former colonial states throughout the developing world.

The invention of nuclear weapons at the end of World War II defined the United States’ commitment to extended deterrence during the Cold War and after. Nuclear weapons are the ultimate deterrent due to their overwhelming destructive potential, which can not only negate any possible state objective but erase civilization.12By contrast, there is little evidence to show that nuclear compellence is common or particularly effective. Todd S. Sechser and Matthew Fuhrmann, “Crisis Bargaining and Nuclear Blackmail,” International Organization 67, no. 1 (January 2013): 173–195. Since the Soviets were thought to have a conventional advantage in mass in Europe throughout the Cold War, the United States’ commitments to its allies depended heavily on its threat to use nuclear weapons if the Soviets invaded Western Europe or attacked Japan.

The United States initially possessed a nuclear monopoly with the invention of the atomic bomb at the end of World War II. The Soviet Union produced its own atom bombs starting in 1949, and over the subsequent decades both sides developed far more destructive thermonuclear weapons and longer-range and more survivable delivery systems—ground-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs).

The quantity, quality, and survivability of each side’s nuclear arsenals eventually gave them both a secure, second-strike retaliatory capability. This means that neither side can score a disarming first strike against the other through a surprise attack; instead, each side can absorb an initial wave of nuclear attacks and still retaliate with enough force to effectively annihilate the other, a condition called “mutually assured destruction” or “MAD.”

Credibility and extended nuclear deterrence

At the heart of nuclear deterrence is the problem of credibility. Since the object of deterrence is the perception of an adversary, there is a psychological dimension that undergirds deterrence between nuclear powers. Whereas Bismarck criticized the impulse to “commit suicide for fear of death,” nuclear deterrence within a condition of MAD is essentially based on the credibility of the claim that one is willing to do just that. Under MAD, nuclear deterrence requires states to commit, effectively, to their own destruction, or at least the mass death of their people. Thus, a 1983 war game that after a week resulted in the mutual annihilation of the U.S. and USSR ended with a final communique from then-secretary of defense Casper Weinberger to Moscow: “May you burn in hell like you are going to burn here.”13William Langewiesche, “The Secret Pentagon War Game that Offers a Stark Warning for Our Times,” New York Times Magazine, December 2, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/12/02/magazine/nuclear-strategy-proud-prophet.html.

Extended deterrence complicates the credibility on which nuclear deterrence rests. States not only must take big risks for allies but risk their own destruction. It’s understandable why, in the pre-nuclear age, a great power might risk a major conventional war to protect allies and prevent the balance of power from swinging dramatically out of favor, such that its own security is imperiled. Under MAD, however, the balance of power matters considerably less for a state’s security, and it therefore has less reason to risk its own existence on behalf of allies.14Robert Jervis, The Meaning of the Nuclear Revolution: Statecraft and the Prospect of Armageddon (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1989). Also see Stephen Van Evera, “A Farewell to Geopolitics,” in To Lead the World: American Strategy after the Bush Doctrine, ed. Melvyn P. Leffler and Jeffrey W. Legro (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 24–50.

Thus, extended nuclear deterrence inherently strains credibility. After all, why should an American president be willing to risk Washington to defend Berlin? This problem was especially acute in the case of the United States’ post-World War II commitments to Germany and Japan, recent enemies the Americans had just played a major role in devastating.

One way the United States sought to shore up its credibility was to deploy troops to these countries to act as a “trip-wire,” signaling to the Soviets that if a shooting war broke out, it might cause Washington to use nuclear weapons. As Thomas Schelling put it, these troops were not there to fight so much as to die.15Schelling, Arms and Influence, 47. Because it was predictable that they would be killed and that the United States would be pulled into a potentially suicidal conflict as a result by events outside its control, the troops’ presence helped make deterrence by punishment more credible.

Another way the United States sought to support the credibility of its core commitments was by fighting peripheral wars in the Third World meant to show a surplus of resolve even where it had only minor interests at stake.16Layne, The Peace of Illusions, 127–132. The costliest example of this misguided logic was the Vietnam War. U.S. involvement in Vietnam was largely premised on the so-called “domino theory,” which posited that a loss of prestige in a peripheral context like Vietnam would call American credibility into question throughout regions of greater strategic importance, opening the way for communist movements to sweep over the contested Third World and for the Soviets to test the United States’ mettle in Europe.17See Jack Snyder, “Introduction” and Robert Jervis, “Domino Beliefs and Strategic Behavior,” in Dominoes and Bandwagons: Strategic Beliefs and Great Power Competition in the Eurasian Rimland, ed. Robert Jervis and Jack Snyder (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1991), 1–50. Yet when the United States finally admitted defeat and the regime in the south fell, the hypothesized “dominoes” did not continue to fall; on the contrary, communist Vietnam almost immediately found itself at war with communist Cambodia and then communist China.

The fears at the heart of the domino theory, and related concerns about credibility which regard “everything as connected to everything,” have little foundation in reality. States rarely choose to bandwagon with a threatening adversary when they have the option to resist or join forces with others to “balance.”18Stephen M. Walt, The Origins of Alliances (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1987). Fears that U.S. allies throughout Asia would cut deals to appease the Soviets or China due to a lack of confidence in American security commitments proved overblown and erroneous. Nor do rival states necessarily judge an adversary’s likely future actions in one context from their past actions in an entirely different context and thereby become emboldened.19Daryl G. Press, Calculating Credibility: How Leaders Assess Military Threats (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005); Jonathan Mercer, Reputation and International Politics (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996). The Soviets did not, as it turns out, infer that the United States’ defeat in Vietnam meant they were unwilling to defend West Berlin, nor is there reason to believe U.S. credibility in Europe would have been in doubt had the U.S. not sacrificed thousands of American lives in Southeast Asia.

Attempting to escape from MAD: counterforce

It was no straightforward task for the United States to convince both the Soviets and its own NATO allies that it would be willing to “trade Washington for Berlin” in a nuclear war.20Layne, The Peace of Illusions, 98–105, 165–166. On the one hand, nuclear stalemate produced strategic stability between the United States and the Soviet Union, compelling them to avoid direct actions that could trigger escalation to nuclear war. On the other hand, nuclear stalemate often made policymakers feel that the threat to use nuclear weapons was itself rendered non-credible without a nuclear advantage or options to escalate below the nuclear threshold.21Lawrence Freedman, The Evolution of Nuclear Strategy, 3rd ed. (New York: Palgrave McMillan, 2003), 215–231, 269–314. As a result, U.S. nuclear strategy during the Cold War often contained opposed tendencies—either seeking to maintain strategic stability within a condition of MAD, or seeking nuclear advantages to deliberately manage or limit the process of escalation.

MAD is closely associated with “countervalue” targeting. “Countervalue” targets an enemy’s cities, with their concentrated civilian populations, industry, and infrastructure. This follows the logic of “deterrence by punishment” to its apex, threatening what an enemy “values” most should it take aggressive action, e.g., if the Soviets invaded West Germany.

“Counterforce,” by contrast, targets an enemy’s military forces, including their nuclear capabilities. Counterforce serves a “damage limitation” strategy, which seeks in the case of a nuclear war to minimize the enemy’s retaliatory capabilities by hitting them, as the saying goes, “the firstest with the mostest,” while accepting that some nuclear retaliation may be inevitable.22The idea behind damage limitation is well expressed by George C. Scott playing the chairman of the Joint Chiefs in the film Dr. Strangelove: “Mr. President, I’m not saying we wouldn’t get our hair mussed! But I do say: no more than 10 to 20 million killed, tops!” By targeting enemy forces and potentially denuding the enemy of its ability to use nuclear weapons, counterforce targeting attempts to escape from MAD—or at least convince enemies that you believe you have escaped and thus maintain your ability to deter them. By targeting military forces, counterforce seeks to make the threat of nuclear war more credible by allowing it, in theory, to remain limited by maintaining the threat of nuking civilian population centers in reserve.23Freedman, The Evolution of Nuclear Strategy, 215–231.

The trouble with MAD, this thinking goes, is that war becomes suicidal and thus hard to threaten, especially on behalf of allies, leading to deterrence failure. This circumstance is called the “stability-instability paradox.”24Glenn H. Snyder, “The Balance of Power and the Balance of Terror,” in The Balance of Power, ed. Paul Seabury (San Francisco, CA: Chandler, 1965), 184–201. This refers to how the “strategic stability” conferred by nuclear stalemate may create instability at the conventional level, in other words, making it conceivable that MAD may still allow for conventional war between nuclear powers. Theoretically, decision-makers in one state may convince themselves that they can press a conventional advantage to their favor and score a fait accompli at the other’s expense, confident that the other will not be willing to respond and risk escalation to all-out nuclear war over an issue below an existential threshold. Yet this may—hence the paradox—trigger the very kind of inadvertent spiral that escalates beyond the conventional level, particularly since the party at a conventional disadvantage has an incentive to escalate to the nuclear level where it has parity.

In order to escape from the credibility problem at the heart of extended deterrence within a condition of MAD, the United States sought at various points during the Cold War to gain nuclear advantages, adopt strategies that would keep nuclear war limited, or control the process of escalation.25Kier A. Lieber and Daryl G. Press, The Myth of the Nuclear Revolution: Power Politics in the Atomic Age (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2020). The most obvious way a state can seek to gain an advantage in capabilities is to increase the size of its own nuclear arsenal. Another is to increase the quality, not the quantity, of its weapons by attaining technological supremacy (say, greater accuracy) while maintaining numerical parity.26When the U.S. and the Soviets signed the ABM treaty in 1972, for instance, the Nixon administration was hoping to lock in numerical parity with the USSR in order to maintain its qualitative superiority in missile technology. John D. Maurer, “The Forgotten Side of Arms Control: Enhancing U.S. Competitive Advantage, Offsetting Enemy Strengths,” War on the Rocks, June 27, 2018, https://warontherocks.com/2018/06/the-forgotten-side-of-arms-control-enhancing-u-s-competitive-advantage-offsetting-enemy-strengths/. Also see John D. Maurer, “The Purposes of Arms Control,” Texas National Security Review 2, no. 1 (November 2018): 8–27. Another option to deter below the level of all-out nuclear war is to seek “escalation dominance”—maintaining an advantage at successive rungs of the “escalation ladder” to deny an adversary the ability to escalate to its advantage.27Herman Kahn, On Escalation: Metaphors and Scenarios (New York: Fredrick A. Praeger, 1965). For a critique, see Michael Fitzsimmons, “The False Allure of Escalation Dominance,” War on the Rocks, November 16, 2017, https://warontherocks.com/2017/11/false-allure-escalation-dominance/. These efforts included bolstering U.S. and allied conventional deterrence and deploying lower yield “tactical” nuclear weapons under battlefield or allied command in order to make a more credible threat to respond to actions below the threshold of strategic nuclear war.

Learning to love a MAD world: the nuclear revolution

Counterforce strategies are seriously flawed, however. For one, counterforce can produce competition and arms racing of the kind described by the “security dilemma,” which undermines strategic stability. As each side attempts to produce more weapons, pursues missile defense, decentralizes command and control, loosens restrictions on use, shuts down diplomatic channels for crisis management, and so on, the possibility for miscalculation or accident increases. This dynamic is hard to suppress; despite multiple arms control agreements between the United States and the Soviet Union, their arsenals nevertheless grew to nearly a combined 70,000 by the end of the Cold War.28Hans Kristensen, et al. “Status of World Nuclear Forces,” Federation of American Scientists, March 29, 2024, https://fas.org/initiative/status-world-nuclear-forces/.

Second, the idea that you can denude any state of its nuclear arsenal with surety, let alone a major nuclear power like the Soviet Union, is doubtful. In reality, leaders rarely think as the stability-instability paradox worries they might.29Benjamin Friedman, Christopher Preble, and Matt Fay, The End of Overkill?: Reassessing U.S. Nuclear Weapons Policy (Washington, D.C.: Cato Institute, 2013). Cold War leaders, as in the Cuban Missile Crisis, tended to worry a great deal about conventional war getting out of control. The substantial caution both the U.S. and Russia show in dealing with each other in Ukraine today demonstrates similar concerns. Examples of conventional war between nuclear powers are also hard to find: the short-lived 1999 Kargil War between India and Pakistan is the primary example.

The Cuban Missile Crisis, in particular, exposed that U.S. leaders doubted the wisdom of counterforce and damage limitation, profoundly calling into question their ability to control escalation and limit a nuclear war to military targets.30Freedman, The Evolution of Nuclear Strategy, 230–231. As President Kennedy said, pushing back against his cabinet’s advice to strike surface-to-air missile sites in Cuba, “It isn’t the first step that concerns me… but both sides escalating to the fourth and fifth step—and we don’t go to the sixth because there is no one around to do so.”31Quoted in Robert F. Kennedy, Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1969), 98. Decades later, Secretary of State Dean Rusk imagined a call between the president and a Soviet leader after initiating a counterforce strike:

We launched our missiles a few minutes ago, but I want to assure you that we are launching them only at military targets, and so we hope that you will leave our cities alone… by the way… we ought to keep this conversation short, because since Moscow is your command and control center, I want to give you time to get down into your shelter.32Quoted in Michael R. Beschloss, The Crisis Years: Kennedy and Khruschev, 1960–1963 (New York: Edward Burlingame Books, 1991), 406–407.

The escalation dynamics exposed by the Cuban Missile Crisis encouraged both sides to develop open lines of communication to manage crises and avoid miscalculation, establishing the famed Moscow-Washington “hotline,” and to pursue arms control measures like the 1963 Nuclear Test Ban Treaty.33On the crisis and its aftermath, see Ernest R. May and Philip D. Zelikow, eds., The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997); Kennedy, Thirteen Days; Beschloss, The Crisis Years, 2–12, 420–602; Aleksandr Fursenko and Timothy Naftali, “One Hell of a Gamble”: Khruschev, Castro, and Kennedy, 1958–1964 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1997), 240–338.

Given the lessons learned from the Cold War, some theorists propose that MAD is not only unavoidable but a blessing in disguise, that the “stability-instability paradox” is at most a minor problem, and that efforts to seek a nuclear advantage are both self-defeating and unnecessary. The “nuclear revolution” hypothesis essentially says that as long as states have secure second-strike capabilities, the possibility of “defeating” or gaining a useful nuclear advantage is both meaningless and potentially suicidal.34Robert Jervis, The Illogic of American Nuclear Strategy (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1984); Jervis, Meaning of the Nuclear Revolution. Since escalation cannot be reliably controlled, the apocalyptic consequences of an escalation to nuclear war powerfully dispose decision-makers to avoid even very low levels of direct conflict. By ensuring that war will not “pay” and by making leaders more risk-averse, the potential for miscalculation is minimized.35On this point (and its ambiguities), see Stephen Van Evera, Causes of War: Power and the Roots of Conflict (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1999), 240–254. The net result, proponents of the nuclear revolution would suggest, is to make conventional war between nuclear-armed states much less likely and international politics more stable.36Kenneth N. Waltz, “Nuclear Myths and Political Realities,” The American Political Science Review 84, no. 3 (September 1990): 731–745.

There is some strong empirical evidence to support the nuclear revolution hypothesis—most obviously the absence of either nuclear war or conventional great power war over the past 80 years. Nuclear weapons have not been “fired in anger” since the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of World War II. The Cold War stayed “cold” because the threat of nuclear war between the U.S. and the USSR compelled them to avoid—even while they constantly prepared for—both eventualities. There is abundant evidence to show that nuclear weapons put the fear of God into decision-makers, impelling them to avoid crises and develop robust mechanisms to manage and mitigate them when they arise.

Retrenching to avoid overextension

The end of the Cold War did not result in the end of the United States’ Cold War military alliances, nor did it reduce the burden of U.S.-backed extended deterrence. Despite—or because of—the fact that it was the only great power in the world and faced no major rival in either Europe or Asia, the United States expanded its alliances and partnerships, while in many cases taking on an even more asymmetric responsibility for defending its allies. Particularly in Europe, where NATO grew to include former members of the Warsaw Pact and the Soviet Union, many of these U.S.-backed security commitments expanded to the point of defying credibility. But with post-Soviet Russia still weak and unable to do more than lodge protests, policymakers in Washington confidently handed out new commitments on top of the old, seemingly assuming they would never have to be honored.

At present, the United States provides extended nuclear deterrence for all 31 other members of NATO, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and a number of Pacific islands and territories. Beyond formal alliances, the United States also remains committed to forms of extended deterrence for a number of informal allies—Israel, Ukraine, Taiwan, and arguably several of the Gulf States—and has become embroiled in several conflicts as a result.37Natalie Armbruster and Benjamin Friedman, “Who Is an Ally, and Why Does It Matter?” Defense Priorities, October 12, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/who-is-an-ally-and-why-does-it-matter/.

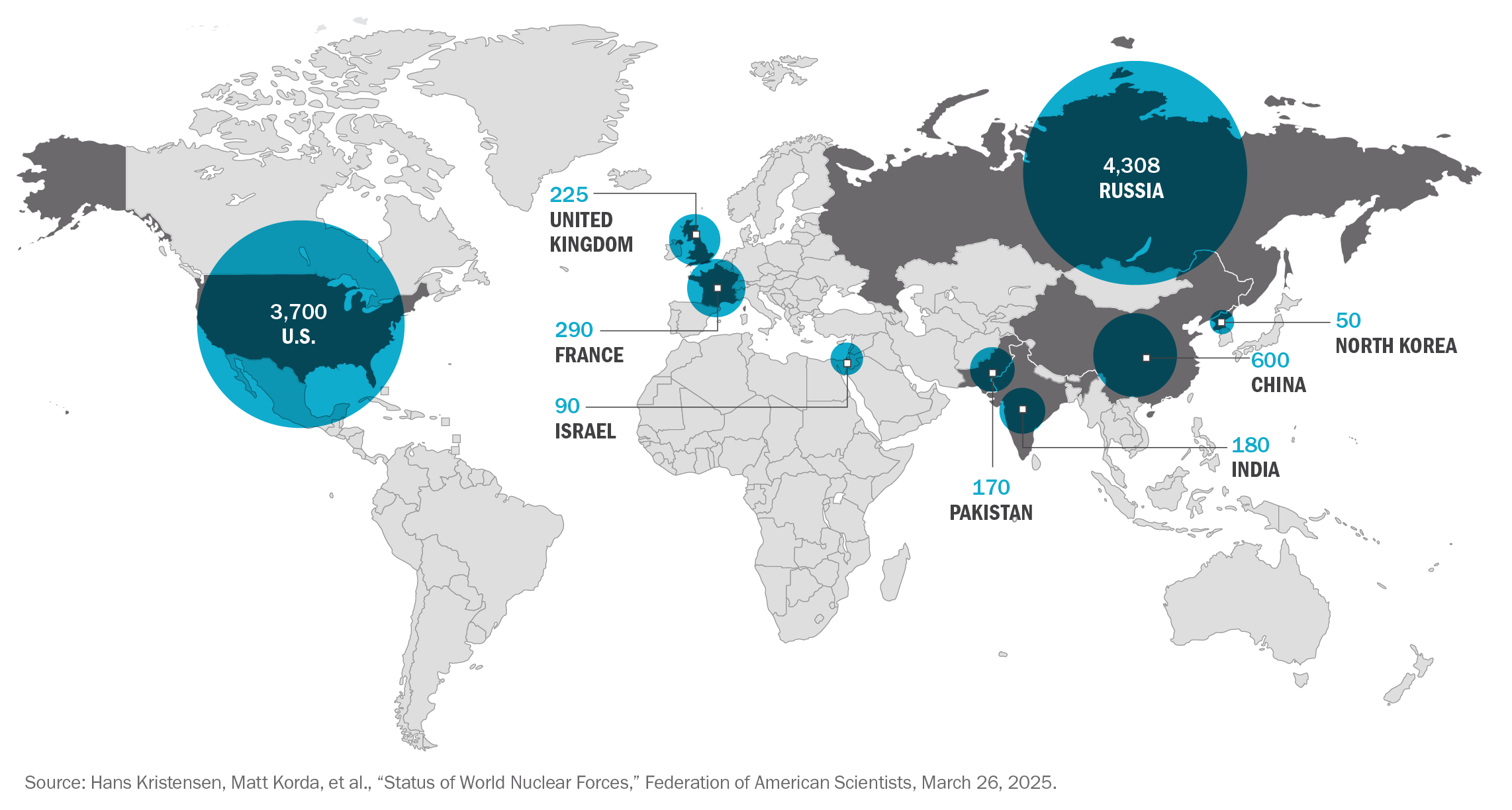

Active nuclear warheads by country

The United States and Russia still by far possess the most nuclear weapons of any nations on earth. The U.S. provides nuclear deterrence for dozens of other countries considered to be under its “nuclear umbrella.”

In the years since the Cold War, the distribution of power has shifted dramatically. China has swiftly developed into a formidable great power with enormous economic and military weight to throw around in East Asia. Russia has also recovered some but by no means all of its former strength. Like all great powers, both countries have significant ambitions to challenge U.S. hegemony and to refashion their regions and the international order in their favor.

Furthermore, in the years since World War II, many of the states in Western Europe and East Asia under U.S. protection have prospered, creating a considerable pool of latent independent power potential. While the United States remains the most powerful country in the world, its share of relative power and wealth has declined since World War II, and indeed since the end of the Cold War.

These combined circumstances reveal a stark figure: the United States’ post-war security guarantees have outlived their original purpose, expanded beyond the scope of vital U.S. interests, and become riskier to maintain in the face of resurgent rivals. The United States also has less relative capacity to sustain them. In summary, the United States’ current alliance commitments make it dangerously overextended.

Extended deterrence also allows security dependents to “free ride” on their patron’s guarantee.38Mancur Olson and Richard Zeckhauser, “An Economic Theory of Alliances,” Review of Economics and Statistics 48, no. 3 (August 1966): 266–279. While the dollar costs of free riding are nothing to sniff at, the more serious problem is that allies allow their own capabilities to atrophy, increasing their dependence on the patron. This may have a deleterious effect on deterrence—which, ironically, is for that ally’s defense above all—especially if the guarantor’s ability to make good diminishes over time. Similarly, dependent allies may “drive recklessly,” provoking more powerful adversaries in the confidence that the guarantor will deal with the consequences.39Barry R. Posen, Restraint: A New Foundation for U.S. Grand Strategy (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2014), 44–50. This too can put the guarantor and dependent alike at greater risk than if the junior ally were responsible for their own defense.

As history shows, strategic overextension can become a vicious cycle of compounding burdens and accelerating decline if a great power does not find ways to gracefully retrench.40Paul Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000 (New York, NY: Random House, 1987); Paul K. MacDonald and Joseph M. Parent, “Graceful Decline? The Surprising Success of Great Power Retrenchment,” International Security 35, no. 4 (Spring 2011): 7–44. The attempt to deter everything everywhere doesn’t sustain credibility; it undermines it and makes it harder to deter real challenges where it matters. The structural imperative for the United States, therefore, has for some time been to downsize its foreign commitments and return to many of its allies and partners the burden of defending themselves.41It’s well worth looking back at projections from 2008 by the National Intelligence Council, Global Trends 2025: A Transformed World, November 2008, https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/Newsroom/Reports%20and%20Pubs/2025_Global_Trends_Final_Report.pdf. To bolster the credibility of its commitments, the United Stated should render them—to use Walter Lippmann’s term—“solvent” by adopting more modest priorities and avoiding unnecessary wars for credibility.42Walter Lippmann, U.S. Foreign Policy: Shield of the Republic (Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1943), 8–10.

Already overextended, the United States should refrain from taking new commitments, particularly where they cross rival great powers’ red lines. The most pressing example is Taiwan, where the local balance of force has shifted markedly in China’s favor. Beijing’s resolve clearly outweighs that of Washington and the potential for catastrophic escalation is profound.43Mark F. Cancian, Matthew Cancian, and Eric Heginbotham, The First Battle of the Next War: Wargaming a Chinese Invasion of Taiwan (Washington, D.C.: Center for Strategic and International Studies, January 2023); Stephen Biddle and Ivan Oelrich, “Future Warfare in the Western Pacific: Chinese Antiaccess/Area Denial, U.S. AirSea Battle, and Command of the Commons in East Asia,” International Security 41, no. 1 (Summer 2016): 7–48; Caitlin Talmadge, “Will China Go Nuclear?: Assessing the Risk of Chinese Nuclear Escalation in a Conventional War with the United States,” International Security 41, no. 4 (Spring 2017): 50–92. The United States should also retract its foolish 2008 pledge to bring Ukraine and Georgia into NATO. Maintaining this promise has not only led Ukraine to ruin and the United States to the brink with Russia, it cannot be credibly maintained in the future given that Washington and its European allies have already declined to defend Ukraine when tested.44For an alternative proposal see Jennifer Kavanagh and Christopher McCallion, “Armed Neutrality for Ukraine Is NATO’s Least Poor Option,” War on the Rocks, February 18, 2025, https://warontherocks.com/2025/02/armed-neutrality-for-ukraine-is-natos-least-poor-option/.

The United States also needs to downsize its existing commitments. The easiest and in many ways most urgent place to do this is Europe, where the United States’ NATO allies have the collective wherewithal to balance the threat posed by Russia and a more plausible interest in risking war to do so. This is particularly true on the alliance’s eastern flank where the extreme difficulty of staging a conventional defense of the Baltic states puts the credibility of the existing alliance under considerable strain.45David A. Shlapak and Michael Johnson, “Reinforcing Deterrence on NATO’s Eastern Flank: Wargaming the Defense of the Baltics,” RAND Corporation, January 29, 2016, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1253.html.

In East Asia, China’s rising power makes deterrence a more challenging—though manageable—problem. While the United States is likely to maintain a significant security role in the region, East Asia’s fragmented island geography and the availability of robust anti-access/area denial systems allow local states to balance against potential Chinese aggression and prevent crucial sea lanes from being controlled by Beijing.46Eugene Gholz, Benjamin Friedman, and Enea Gjoza, “Defensive Defense: A Better Way to Protect U.S. Allies in Asia,” Washington Quarterly 42, no. 4 (Winter 2020): 171–189; Eric Heginbotham and Jacob L. Heim, “Deterring Without Dominance: Discouraging Chinese Adventurism Under Austerity,” Washington Quarterly 38, no. 1 (Spring 2015): 185–199. China’s political geography, which includes numerous long land and sea borders, require it to spread its strategic attention in a number of different directions across an enormous area. It is in the interest of the United States and its allies in the Western Pacific to keep Beijing’s focus inland, avoid provoking Beijing or triggering a security dilemma while maintaining the defensive capabilities to contain China should it—improbably—go on an expansionist rampage.

Many fear that if the United States scales back its alliances, there will be an uncontrolled cascade of nuclear proliferation as states previously under the U.S. “nuclear umbrella” scramble to avoid being caught defenseless. There are good reasons to believe these fears are overstated, however, and that the managed acquisition of nuclear weapons by regional powers like Germany, Japan, and South Korea could be stabilizing.

In the first place, the main threats in Asia and Europe—China, Russia, and North Korea—already have nukes. Should Germany, Japan, or South Korea acquire their own nuclear deterrents to gain peace of mind, there is little reason why their allies and neighbors should find their commitment less credible than that of the distant and more inherently secure United States. Moreover, the security of states in each region are interdependent insofar as they must balance against their more powerful neighbors. It would therefore be counterproductive for them to acquire deterrents targeting one another. Small states like Vietnam already make their way in the world without nuclear weapons and without protection from the United States. Rather than a cascade of proliferation, therefore, it’s reasonable to believe that proliferation would be limited to a few relatively wealthy and populous states currently under the U.S. nuclear umbrella.

Conclusion

Deterrence depends on a combination of capabilities and resolve, along with an implicit assurance towards an adversary. Extended deterrence strains both capabilities and resolve, and has a tendency to promote a more implacable stance toward competitors in order to compensate for the resulting lack in credibility. Especially as the United States’ relative share of wealth and power declines and new great powers emerge, its ability to provide deterrence on behalf of its allies has come under ever more strain, putting it in greater danger of becoming entangled in unnecessary wars.

The United States’ commitments to its dozens of allies across Europe and Asia have outlived the strategic rationale of the early Cold War, especially as those allies have themselves grown capable of providing for their own security. The United States should downsize its commitments, only establishing alliances if dictated by the priority of preventing major imbalances of power on the industrialized flanks of Eurasia.

Endnotes

- 1John J. Mearsheimer, Conventional Deterrence (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1983), 14.

- 2Thomas C. Schelling, Arms and Influence (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 69–91.

- 3Kenneth N. Waltz, Theory of International Politics (Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, 1979), 74–77; Kenneth N. Waltz, “Reflections on Theory of International Politics: A Response to My Critics,” in Neorealism and Its Discontents, ed. Robert O. Keohane (New York: Columbia University Press, 1986), 331–337, 341–344.

- 4Michael J. Mazarr, Understanding Deterrence (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2018), 2–3.

- 5Mazarr, Understanding Deterrence, 2–3.

- 6Schelling, Arms and Influence, 74–75.

- 7Schelling, Arms and Influence, 74.

- 8John H. Herz, “Idealist Internationalism and the Security Dilemma,” World Politics 2, no. 2 (January 1950): 157–180; Robert Jervis, Perception and Misperception in International Politics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976), 58–113; Robert Jervis, “Cooperation Under the Security Dilemma,” World Politics 30, no. 2 (January 1978): 167–214.

- 9Jervis, Perception and Misperception, 94–96.

- 10Jervis, Perception and Misperception, 82; Jervis, “Cooperation Under the Security Dilemma.”

- 11For Kennan’s thought, see John Lewis Gaddis, Strategies of Containment: A Critical Appraisal of American National Security Policy During the Cold War, rev. and expanded ed. (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2005), 24–86. For the importance of the Eurasian rimland in U.S. strategy, see Nicholas J. Spykman, The Geography of the Peace, ed. Helen R. Nicholl (New York: Harcourt, Brace, and Company, 1944). For the expansion of U.S. grand strategy into “extraregional hegemony,” see Christopher Layne, The Peace of Illusions: American Grand Strategy from 1940 to the Present (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2006), 39–117.

- 12By contrast, there is little evidence to show that nuclear compellence is common or particularly effective. Todd S. Sechser and Matthew Fuhrmann, “Crisis Bargaining and Nuclear Blackmail,” International Organization 67, no. 1 (January 2013): 173–195.

- 13William Langewiesche, “The Secret Pentagon War Game that Offers a Stark Warning for Our Times,” New York Times Magazine, December 2, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/12/02/magazine/nuclear-strategy-proud-prophet.html.

- 14Robert Jervis, The Meaning of the Nuclear Revolution: Statecraft and the Prospect of Armageddon (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1989). Also see Stephen Van Evera, “A Farewell to Geopolitics,” in To Lead the World: American Strategy after the Bush Doctrine, ed. Melvyn P. Leffler and Jeffrey W. Legro (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 24–50.

- 15Schelling, Arms and Influence, 47.

- 16Layne, The Peace of Illusions, 127–132.

- 17See Jack Snyder, “Introduction” and Robert Jervis, “Domino Beliefs and Strategic Behavior,” in Dominoes and Bandwagons: Strategic Beliefs and Great Power Competition in the Eurasian Rimland, ed. Robert Jervis and Jack Snyder (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1991), 1–50.

- 18Stephen M. Walt, The Origins of Alliances (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1987).

- 19Daryl G. Press, Calculating Credibility: How Leaders Assess Military Threats (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005); Jonathan Mercer, Reputation and International Politics (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996).

- 20Layne, The Peace of Illusions, 98–105, 165–166.

- 21Lawrence Freedman, The Evolution of Nuclear Strategy, 3rd ed. (New York: Palgrave McMillan, 2003), 215–231, 269–314.

- 22The idea behind damage limitation is well expressed by George C. Scott playing the chairman of the Joint Chiefs in the film Dr. Strangelove: “Mr. President, I’m not saying we wouldn’t get our hair mussed! But I do say: no more than 10 to 20 million killed, tops!”

- 23Freedman, The Evolution of Nuclear Strategy, 215–231.

- 24Glenn H. Snyder, “The Balance of Power and the Balance of Terror,” in The Balance of Power, ed. Paul Seabury (San Francisco, CA: Chandler, 1965), 184–201.

- 25Kier A. Lieber and Daryl G. Press, The Myth of the Nuclear Revolution: Power Politics in the Atomic Age (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2020).

- 26When the U.S. and the Soviets signed the ABM treaty in 1972, for instance, the Nixon administration was hoping to lock in numerical parity with the USSR in order to maintain its qualitative superiority in missile technology. John D. Maurer, “The Forgotten Side of Arms Control: Enhancing U.S. Competitive Advantage, Offsetting Enemy Strengths,” War on the Rocks, June 27, 2018, https://warontherocks.com/2018/06/the-forgotten-side-of-arms-control-enhancing-u-s-competitive-advantage-offsetting-enemy-strengths/. Also see John D. Maurer, “The Purposes of Arms Control,” Texas National Security Review 2, no. 1 (November 2018): 8–27.

- 27Herman Kahn, On Escalation: Metaphors and Scenarios (New York: Fredrick A. Praeger, 1965). For a critique, see Michael Fitzsimmons, “The False Allure of Escalation Dominance,” War on the Rocks, November 16, 2017, https://warontherocks.com/2017/11/false-allure-escalation-dominance/.

- 28Hans Kristensen, et al. “Status of World Nuclear Forces,” Federation of American Scientists, March 29, 2024, https://fas.org/initiative/status-world-nuclear-forces/.

- 29Benjamin Friedman, Christopher Preble, and Matt Fay, The End of Overkill?: Reassessing U.S. Nuclear Weapons Policy (Washington, D.C.: Cato Institute, 2013).

- 30Freedman, The Evolution of Nuclear Strategy, 230–231.

- 31Quoted in Robert F. Kennedy, Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1969), 98.

- 32Quoted in Michael R. Beschloss, The Crisis Years: Kennedy and Khruschev, 1960–1963 (New York: Edward Burlingame Books, 1991), 406–407.

- 33On the crisis and its aftermath, see Ernest R. May and Philip D. Zelikow, eds., The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997); Kennedy, Thirteen Days; Beschloss, The Crisis Years, 2–12, 420–602; Aleksandr Fursenko and Timothy Naftali, “One Hell of a Gamble”: Khruschev, Castro, and Kennedy, 1958–1964 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1997), 240–338.

- 34Robert Jervis, The Illogic of American Nuclear Strategy (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1984); Jervis, Meaning of the Nuclear Revolution.

- 35On this point (and its ambiguities), see Stephen Van Evera, Causes of War: Power and the Roots of Conflict (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1999), 240–254.

- 36Kenneth N. Waltz, “Nuclear Myths and Political Realities,” The American Political Science Review 84, no. 3 (September 1990): 731–745.

- 37Natalie Armbruster and Benjamin Friedman, “Who Is an Ally, and Why Does It Matter?” Defense Priorities, October 12, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/who-is-an-ally-and-why-does-it-matter/.

- 38Mancur Olson and Richard Zeckhauser, “An Economic Theory of Alliances,” Review of Economics and Statistics 48, no. 3 (August 1966): 266–279.

- 39Barry R. Posen, Restraint: A New Foundation for U.S. Grand Strategy (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2014), 44–50.

- 40Paul Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000 (New York, NY: Random House, 1987); Paul K. MacDonald and Joseph M. Parent, “Graceful Decline? The Surprising Success of Great Power Retrenchment,” International Security 35, no. 4 (Spring 2011): 7–44.

- 41It’s well worth looking back at projections from 2008 by the National Intelligence Council, Global Trends 2025: A Transformed World, November 2008, https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/Newsroom/Reports%20and%20Pubs/2025_Global_Trends_Final_Report.pdf.

- 42Walter Lippmann, U.S. Foreign Policy: Shield of the Republic (Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1943), 8–10.

- 43Mark F. Cancian, Matthew Cancian, and Eric Heginbotham, The First Battle of the Next War: Wargaming a Chinese Invasion of Taiwan (Washington, D.C.: Center for Strategic and International Studies, January 2023); Stephen Biddle and Ivan Oelrich, “Future Warfare in the Western Pacific: Chinese Antiaccess/Area Denial, U.S. AirSea Battle, and Command of the Commons in East Asia,” International Security 41, no. 1 (Summer 2016): 7–48; Caitlin Talmadge, “Will China Go Nuclear?: Assessing the Risk of Chinese Nuclear Escalation in a Conventional War with the United States,” International Security 41, no. 4 (Spring 2017): 50–92.

- 44For an alternative proposal see Jennifer Kavanagh and Christopher McCallion, “Armed Neutrality for Ukraine Is NATO’s Least Poor Option,” War on the Rocks, February 18, 2025, https://warontherocks.com/2025/02/armed-neutrality-for-ukraine-is-natos-least-poor-option/.

- 45David A. Shlapak and Michael Johnson, “Reinforcing Deterrence on NATO’s Eastern Flank: Wargaming the Defense of the Baltics,” RAND Corporation, January 29, 2016, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1253.html.

- 46Eugene Gholz, Benjamin Friedman, and Enea Gjoza, “Defensive Defense: A Better Way to Protect U.S. Allies in Asia,” Washington Quarterly 42, no. 4 (Winter 2020): 171–189; Eric Heginbotham and Jacob L. Heim, “Deterring Without Dominance: Discouraging Chinese Adventurism Under Austerity,” Washington Quarterly 38, no. 1 (Spring 2015): 185–199.

The Latest

October 17, 2025

Events on Deterrence