May 6, 2020

Debunking the safe haven myth

By Daniel Davis

Key points

- The post-9/11 mission in Afghanistan swiftly succeeded when U.S. forces decimated Al-Qaeda and punished the Taliban for harboring them. That victory was squandered when policymakers transitioned to a transformative nation building project, rather than withdraw U.S. forces and deter future terrorism through narrowly focused operations.

- Preventing “safe havens” through nation building was premised on two false assumptions: (1) that terrorists depend on unruled or poorly ruled territory to operate and (2) that terrorists would gain haven in Afghanistan in the absence of U.S. ground forces.

- The U.S. is safe from terrorism because of its capability to gather intelligence on, and strike, anti-U.S. terrorists anywhere. Cooperative and stable governments aid counterterror efforts, but the U.S. can locate and destroy terrorists even in their absence.

- U.S. counterterror capabilities have only improved over the years—and U.S. political will to target terrorists, once lacking, is now unquestionable. Full withdrawal from Afghanistan ends a costly conflict with no loss to U.S security and is long overdue.

The “safe haven” myth

The nearly two decade-long U.S. military presence in Afghanistan has been justified on the basis that withdrawing U.S. forces would create a “safe haven” for terrorists to plan and operate from, inviting a second 9/11.1A variety of other authors have lamented how the “safe haven” myth fuels endless war. A partial list includes: Stephen M. Walt, “The ‘Safe Haven’ Myth,” Foreign Policy, August 18, 2009, https://foreignpolicy.com/2009/08/18/the-safe-haven-myth; John Mueller, “The ‘Safe Haven’ Myth,” The Nation, October 21, 2009, https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/safe-haven-myth/; Micah Zenko and Amelia Mae Wolf, “The Myth of the Terrorist Safe Haven,” Foreign Policy, January 26, 2016, https://foreignpolicy.com/2015/01/26/al-qaeda-islamic-state-myth-of-the-terrorist-safe-haven/; Paul R. Pillar, “The Safe Haven Notion,” National Interest, August 29, 2017, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/paul-pillar/the-safe-haven-notion-22099. But Afghanistan is not unique in its potential to host terrorists, and the U.S. retains the capability to destroy terrorists globally, including in Afghanistan, without a permanent military ground presence.

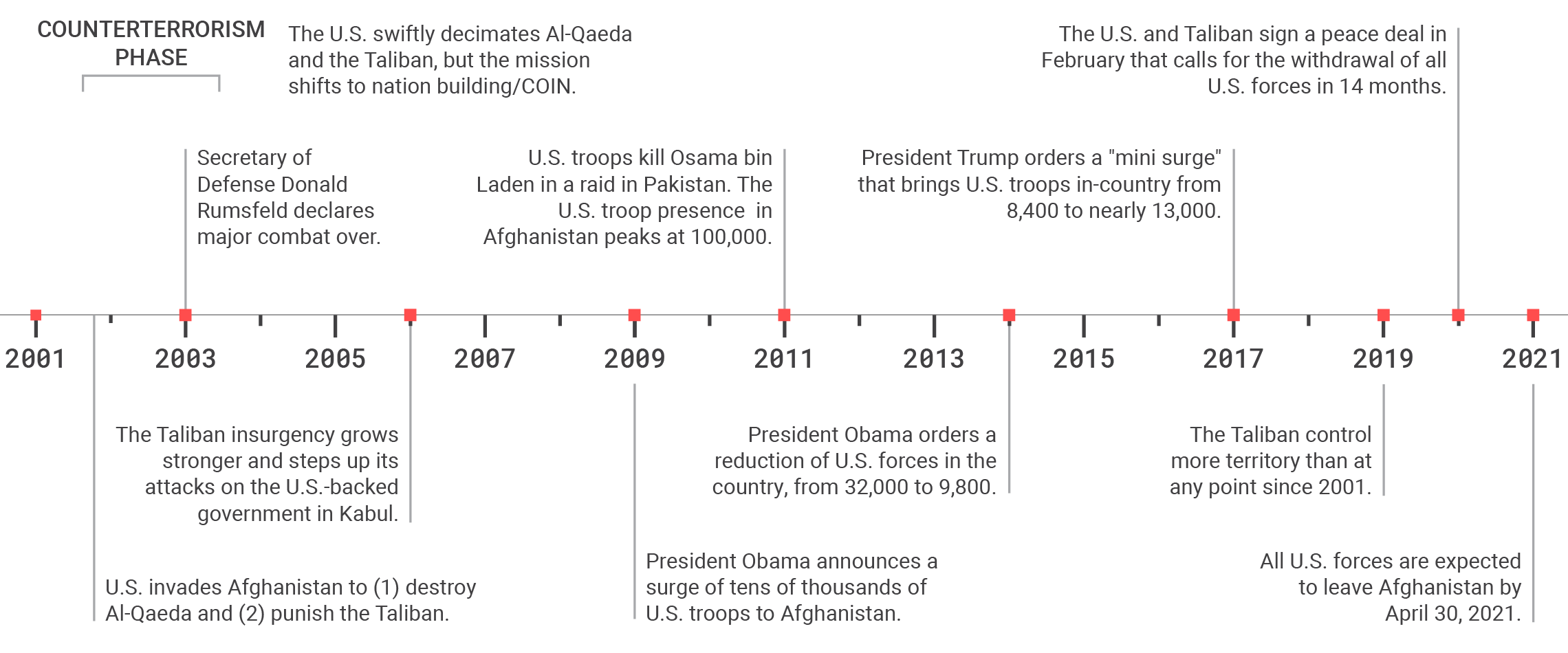

Timeline of U.S. military operations in Afghanistan

The initial goals of the U.S. invasion were swiftly achieved. By 2003, major combat operations in Afghanistan officially ended. By transitioning to a nation building effort, rather than withdrawing, the U.S. remained enmeshed in Afghanistan’s civil war. Repeated surges have failed to blunt the momentum of the Taliban insurgency, and the Afghan government has proven incapable of securing the country.

Remaining in Afghanistan fails to make the U.S. safer while imposing considerable costs on the U.S. and our military forces—negatively impacting our ability to defend ourselves where it matters the most.

Following the 2001 attacks, the U.S. rightly sought to dismantle global terrorist organizations and punish those who had protected or tolerated Al-Qaeda. The initial U.S. campaign in Afghanistan did just that, overthrowing the Taliban government and decimating Al-Qaeda’s membership. But U.S. strategists learned the wrong lessons from 9/11, believing that a U.S.-friendly government in Kabul was both possible and necessary to prevent future anti-American terrorism originating in Afghanistan. This led to an 18-year-and-counting nation building effort that has failed to yield any lasting successes, while imposing massive and ongoing costs to the U.S.

The misapprehension that hinders U.S. counterterrorism policy is the idea that hostile states and “failed states”—those where the government lacks a monopoly on violence within its borders—provide terrorists “safe haven” to attack the United States or other Western countries. Supporters of continuing the war in Afghanistan argue that 9/11 happened because Afghanistan lacked effective governance, allowing Al-Qaeda to operate freely. A U.S. withdrawal would allegedly allow the Taliban to overthrow the Afghan government and recreate the same conditions.

But nation building and counterterrorism are distinct goals, and the failures that made 9/11 possible did not directly stem from political disorder in Afghanistan. Instead, 9/11 occurred because the U.S. underestimated the threat terrorists posed, made half-hearted efforts to disrupt their networks abroad, and failed to implement effective homeland security measures. Washington had multiple opportunities to eliminate Osama bin Laden before the attacks took place but declined, believing the risks of a strike to outweigh the benefits. And although Afghanistan served as a base of operations for Al-Qaeda, the attacks were planned across several different countries, with the key terrorists operating freely within the U.S. itself.

The U.S. has for decades had the capability to locate and kill hostile individuals abroad, due to aerial surveillance and strike technology. This capability has been substantially enhanced since 9/11. The political will of the U.S. to pursue terrorists and their enablers is also unquestionable—the aggressive counterterrorism measures of the past two decades have made that clear. The homeland security flaws 9/11 exposed have also been corrected, and a vast surveillance and law enforcement apparatus has been built to protect the nation from anti-U.S. terrorist attacks.

Afghanistan was not necessary to carry out 9/11

Americans have been repeatedly warned that “abandoning” Afghanistan would have disastrous consequences for U.S. security. In 2009, President Barack Obama ordered the first of what would be two major troop surges that year, arguing that, “If the Afghan government falls to the Taliban—or allows Al-Qaeda to go unchallenged—that country will again be a base for terrorists who want to kill as many of our people as they possibly can.”2“President Obama’s Remarks on New Strategy for Afghanistan and Pakistan,” New York Times, March 27, 2009, https://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/27/us/politics/27obama-text.html. Nine years later, Secretary of Defense James Mattis would offer a similar argument—that the U.S. was in Afghanistan to prevent it from being a launching pad for transnational terrorism, and could not leave until the Afghan military was self-sufficient and the Afghan government and Taliban had arrived at a peace agreement.3The Associated Press, “Mattis in Kabul: We ‘look toward a victory in Afghanistan—not a military victory,’” Politico, March 13, 2018, https://www.politico.com/story/2018/03/13/jim-mattis-afghanistan-end-game-458325.

But much of the groundwork for the 9/11 attacks was laid outside Afghanistan. The most definitive account of how the initial 9/11 plot was conceived, planned, and prepared comes from the 9/11 Commission Report (“the Report”) published in 2004.4National Commission on Terrorist Attacks, The 9/11 Commission Report (Washington, DC: Norton, 2004), https://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. As the Commission lays out in painstaking detail, Afghanistan was incidental to the attack’s planning. Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (KSM) conceived the attack beginning as far back as 1993 while living in Qatar. A key collaborator, Ramzi Yousef, was based in the Philippines.59/11 Commission Report. p. 59

Al-Qaeda was not fully formed during this time, and according to the Report, the early planning for the attack was not even an Al-Qaeda operation. KSM refined his plans for what would later become the 9/11 attacks from his global travels between 1993 and 1996 and subsequently arranged a meeting with bin Laden, who was busy working independently of KSM to form and strengthen Al-Qaeda.

After initially fighting against the Soviets in Afghanistan, bin Laden turned increasingly hostile toward the West in the years after the war’s end. By 1994, Saudi Arabia stripped him of his citizenship, and bin Laden went to Sudan in exile. In mid-1996, bin Laden moved his operations from Sudan to Afghanistan, and finally gave KSM approval for the 9/11 operation sometime in late 1998 or early 1999.69/11 Commission Report. p. 149 KSM then moved to Afghanistan, and in “late 1998 to early 1999, planning for the 9/11 operation began in earnest.”79/11 Commission Report. p. 150

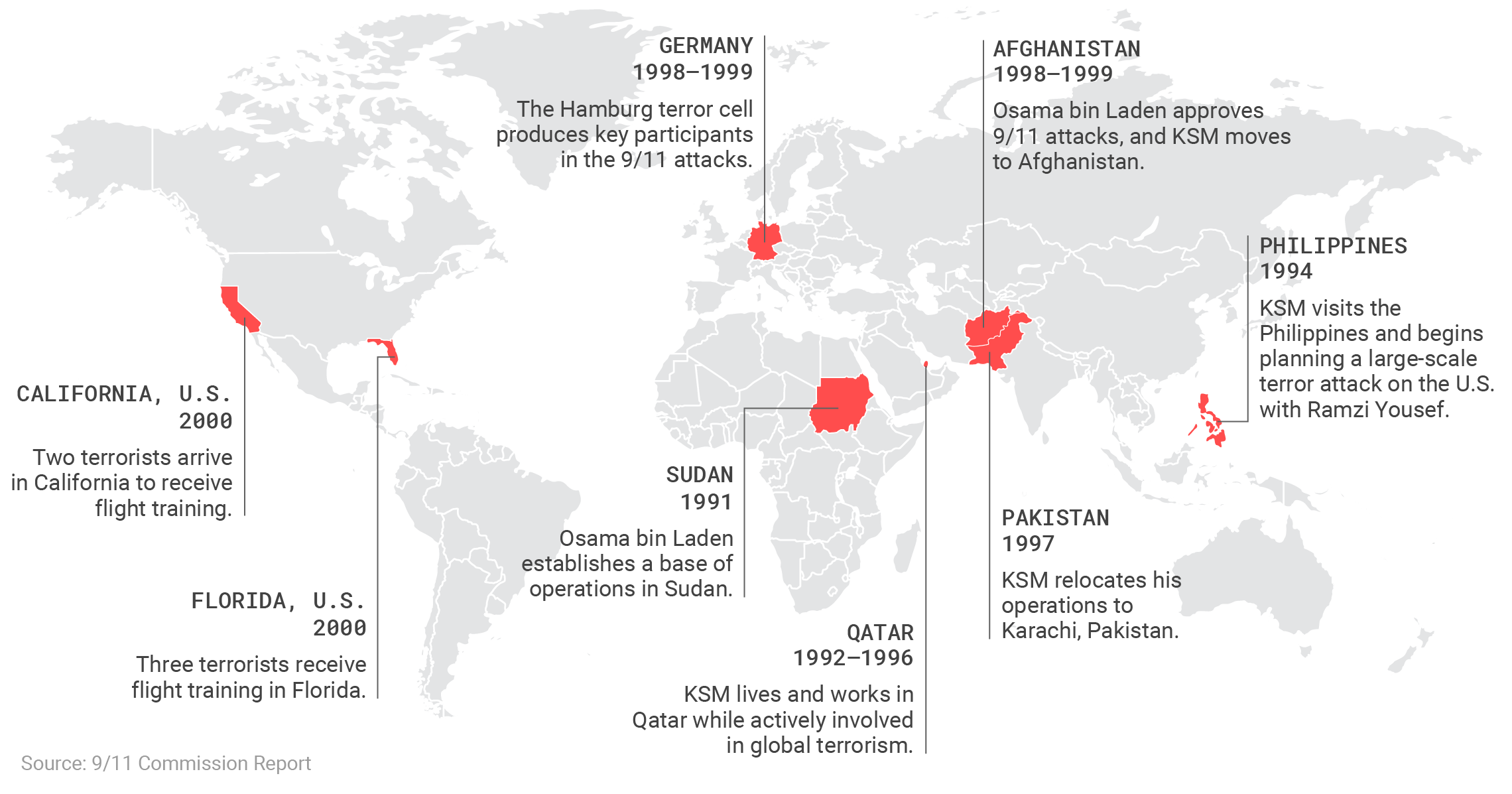

Key events and locations leading up to the 9/11 attacks

The 9/11 attacks were the result of preparation and planning carried out in numerous countries, including the U.S. itself. The terrorists involved were transnational, and Afghanistan was not unique in providing a venue for them to organize.

While Afghanistan is associated with 9/11 because it served as bin Laden’s residence, the attack was conceived, planned, and executed by Al-Qaeda members operating out of numerous countries, including the U.S. KSM, the mastermind of the plot, formed his initial concept over a three year period between 1993–1996 while living and traveling in Sudan, Yemen, Malaysia, and Brazil, and after the single meeting with bin Laden in Tora Bora in 1996, continued refining his plan in India, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Pakistan.

Afghanistan is by no means unique in its ability to host terrorists. Had bin Laden continued living in Sudan, planning could have happened there. It could have occurred in Pakistan, Malaysia, Chechnya, the Philippines, other nations with Al-Qaeda cells, or elsewhere. Much of the operational planning and rehearsing was not conducted in Afghanistan, but in Germany. The most important training took place in the U.S. itself. The 9/11 plot was conceived by a group of internationally mobile terrorists with access to hideouts in several countries, and its operation grew out of a permissive security environment for terrorism worldwide, rather than access to Afghanistan specifically. Global vigilance against terrorism is appropriate but should not be confused with occupying Afghanistan.8Benjamin H. Friedman, “Sri Lanka Bombings Do Not Mean There’s an ISIS Worth Fighting,” USA Today, April 29, 2019, https://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2019/04/29/sri-lanka-bombings-dont-mean-isis-worth-fighting-editorials-debates/3622310002/.

Even under Taliban control, Afghanistan-based terrorists were never outside of U.S. reach

Even before 9/11, the U.S. possessed the intelligence gathering and targeting capability to locate and kill key terrorists (including bin Laden) anywhere in the world. It’s worth noting, however, that while a figure like bin Laden is uniquely dangerous and his death would have been a blow to Al-Qaeda, there is no guarantee it would have stopped the 9/11 attacks.

On August 7, 1998, U.S. embassies in Tanzania and Kenya were bombed, killing 224 people and wounding more than 5,000. Less than two weeks later, President Bill Clinton ordered a retaliatory strike against suspected terrorist bases in Afghanistan and Sudan, hoping to kill bin Laden, the bombing’s mastermind.9C-SPAN, “U.S. Strikes Against Terrorist Bases,” filmed August 1998 in Washington, DC, video, 7:55, https://www.c-span.org/video/?110184-1/us-strikes-terrorist-bases. When it became clear bin Laden survived, the U.S. on November 4, 1998, charged him with 224 counts of murder and the CIA began aggressively seeking opportunities to kill or capture him.

In February 1999, the CIA had detailed intelligence pinpointing the location of bin Laden at an isolated hunting camp in the desert near Kandahar. The trigger was never pulled because of political concerns in the White House. At the time, the administration believed the risks of a successful strike outweighed the benefits.

In May 1999, the U.S. got its at least third—and last—chance to eliminate bin Laden prior to 9/11. “CIA assets in Afghanistan reported on bin Laden’s location in and around Kandahar,” the Report stated.109/11 Commission Report. p. 140 Yet again senior officials in both the CIA and Pentagon were reluctant to authorize the strike—and the chance to kill bin Laden was lost for the last time. A CIA official at the scene expressed anger at “having a chance to get [bin Laden] three times in 36 hours and foregoing the chance each time.”119/11 Commission Report. p. 140

The Report notes nine decisions points—as opposed to clear shots—between 1998 and 2000 where a different approach might have allowed U.S. or U.S.-backed forces to kill bin Laden. The problem was not necessarily a lack of capability—although armed drones would have helped—but the fact policymakers chose not to proceed.12Glenn Kessler, “Bill Clinton and the Missed Opportunities to Kill Osama bin Laden,” Washington Post, February 16, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/fact-checker/wp/2016/02/16/bill-clinton-and-the-missed-opportunities-to-kill-osama-bin-laden. Today, the U.S. possesses the motivation and capability to hunt terrorists wherever they take refuge.

These episodes demonstrate claims by senior officials—that troops on the ground in Afghanistan are necessary to keep us safe at home—have no basis. Despite having no forces in Afghanistan, the U.S. cultivated the intelligence necessary to locate the leader behind the 9/11 plot and created nine opportunities to kill him before the homeland was attacked.

The military is fighting a counterinsurgency on behalf of Kabul, not a counterterror mission against anti-U.S. threats

The initial U.S. combat mission in Afghanistan in October 2001 was explicitly and directly a counterterror operation targeting the transnational terror threat (Al-Qaeda) and their national host (the Taliban). However, from about 2003 forward the vast majority of the U.S. mission has been counterinsurgency, which is wholly disconnected from U.S. national security.

The initial U.S. invasion of Afghanistan ordered by President George W.Bush was punitive—designed to destroy Al-Qaeda’s presence in Afghanistan and punish the Taliban for hosting them. That operation was a success. The Taliban were driven from power and Al-Qaeda’s membership was decimated, with most of its members killed or forced to flee to Pakistan. President Bush’s initial mandate to the military—”to disrupt the use of Afghanistan as a terrorist base of operations and to attack the military capability of the Taliban regime”—was accomplished by the summer of 2002.

The U.S. stumbled when, instead of accepting victory and withdrawing, it expanded the mission from one of destroying anti-U.S. terrorists to building a centralized, democratic, and self-sufficient Afghan state—something without precedent in Afghanistan’s history. According to President Bush, “one of the lessons of that September the 11th day is that we cannot allow terrorists to gain sanctuary anywhere, and we must not allow them to reestablish the safe haven they lost in Afghanistan. Our goal in Afghanistan is to help the people of that country to defeat the terrorists and establish a stable, moderate, and democratic state that respects the rights of its citizens, governs its territory effectively, and is a reliable ally in this war against extremists and terrorists.”13“President Bush Discusses Progress in Afghanistan, Global War on Terror,” The White House, February 15, 2007, https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2007/02/20070215-1.html.

U.S. policymakers believed that states with hostile, weak, or no governments were breeding grounds for terrorism and the way to prevent terrorists from operating freely would be to create a friendly, effective government from scratch. To that end, the U.S. sought to prop up Kabul at all costs. Unlike President Bush’s original set of objectives, however, this mission is not only unnecessary, but also virtually impossible to accomplish—requiring the military to build a unified, well-ordered society where none existed. Nearly 18 years of war later, the Taliban hold more territory than at any point since 2001, and the Afghan government remains unpopular, corrupt, and dependent on foreign aid.

More important, the current U.S. war in Afghanistan is not being fought against anti-U.S. terrorists, but rather insurgents seeking to seize political power in their own country. The U.S. failed to distinguish between Islamist insurgents with local motivations and anti-U.S. Islamist terrorists and as a result spent years fighting adversaries that lacked the ambition and capabilities to attack the U.S. itself.

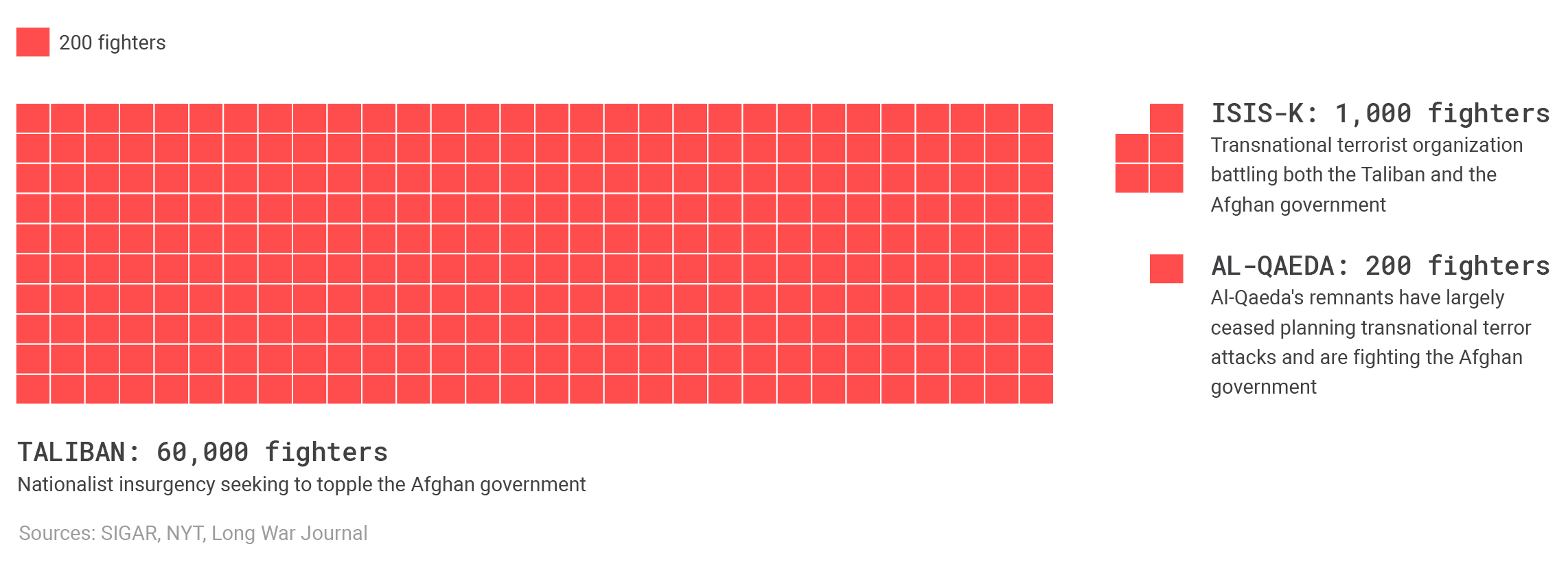

Breakdown of anti-Kabul insurgents versus anti-U.S. terrorists

The U.S. is primarily fighting anti-Kabul insurgents, not anti-U.S. terrorists, in Afghanistan. Transnational terrorists make up only a small portion of opposition forces.

Taliban recruitment is largely driven by disaffected Pashtuns angry at Kabul’s corruption and incompetence and at what they see as a U.S. occupation of their homeland. However, the Taliban have shown no appetite for engaging in anti-American terrorism outside of Afghanistan, and in fact are hostile to more radical groups, like ISIS in Afghanistan (ISIS-K).14Katie Bo Williams, “The U.S. Is Helping the Taliban Fight ISIS, CENTCOM’s Top General Says,” Defense One, March 10, 2020, https://www.defenseone.com/threats/2020/03/us-helping-taliban-fight-isis-top-general/163665/.

While U.S. troops can prevent Kabul from falling as long as they remain, they cannot make Afghan politicians govern effectively, force the Afghan army and police units to protect their people without preying on them, compel the various tribes and warlords to work together, or eradicate the opium trade. Nation building has been an unequivocal failure, and all evidence indicates a continued U.S. presence—no matter how long—would yield no better outcomes than what we have already achieved. If anything, extending our presence could lead to exit under even worse conditions than today.

Even at the peak of the U.S. presence in Afghanistan, there were substantial parts of the country that the U.S. did not patrol, let alone control. During the 2010–2014 Afghan surge, there were as many as 140,000 U.S. and NATO troops in-country, yet they could not achieve a lasting victory. That is no surprise considering how much nation building demands of the military. No amount of acceptable force (short of widespread, brutal repression) is sufficient for remaking a nation hobbled by poverty, corruption, and infighting into a modern, well-run state. Fortunately, U.S. security isn’t contingent on succeeding at this venture.

The U.S. doesn’t need to and shouldn’t occupy foreign nations to fight terrorism

The U.S. has the ability to project power globally via aircraft carriers, strategic lift from the Air Force and Navy, and the Army’s ability to launch operations from those platforms. The U.S. military’s ISR-Strike system—merging robust global intelligence operations, high-tech surveillance and strike capabilities, along with skilled field operatives and local assets on the ground—has contributed to protecting the U.S. homeland. Our ability to locate terrorists hiding in remote locations and conduct strikes to eliminate them has only improved since 9/11, as graphically demonstrated in the 2011 operation that killed bin Laden in Pakistan, the 2018 strike on ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in Syria, and the 2020 raid to kill the leader of Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula in Yemen.15“How Osama bin Laden Was Located and Killed,” New York Times, May 8, 2011, https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/interactive/2011/05/02/world/asia/abbottabad-map-of-where-osama-bin-laden-was-killed.html; Alex Ward, “‘Jackpot’: Inside the U.S. Military Raid to Kill ISIS Leader Baghdadi,” Vox, October 28, 2019, https://www.vox.com/2019/10/28/20936137/isis-baghdadi-raid-military-dog; Shane Harris, Anne Gearan, and Ellen Nakashima, “U.S. Targets Leader of Al-Qaeda in Yemen,” Washington Post, February 1, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/us-targets-leader-of-al-qaeda-in-yemen/2020/02/01/b4284f6a-450b-11ea-abff-5ab1ba98b405_story.html. No place on Earth is beyond our reach.

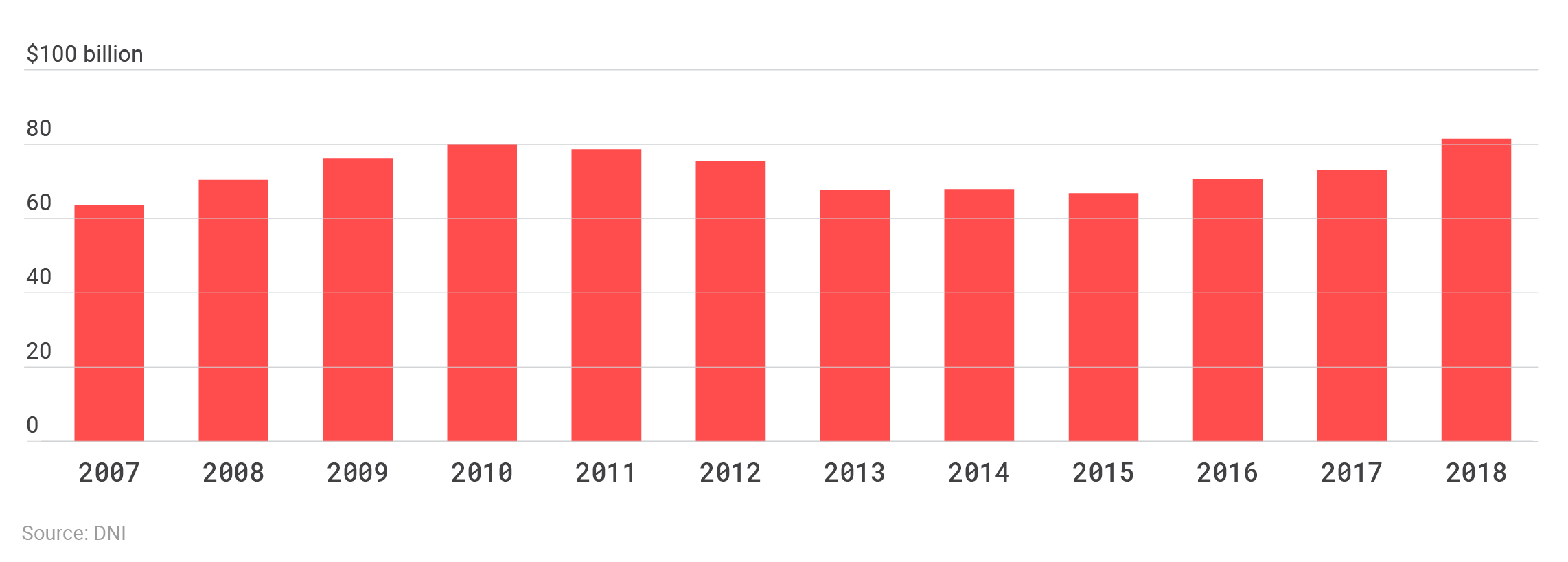

U.S. ISR-Strike is composed of systems that integrate and process information from a wide variety of sources, satellites, and other tools to monitor potential threats in real time and weapons systems that can be deployed to strike targets once a decision has been made.16Richard A. Best, Jr., “Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) Programs: Issues for Congress,” CRS Report for Congress, last modified February 22, 2005, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/intel/RL32508.pdf. A major portion of the $60 to $70 billion spent annually on intelligence in the U.S. is invested in this capability.17Best, “Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance.” In addition to the intelligence community, the military has also developed its own ISR-Strike tools, with the Air Force alone operating 425 manned and unmanned aircraft of 14 different types dedicated to that purpose.18Robert Stiegel, “Is the Air Force Serious About Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance?” War on the Rocks, June 25, 2019, https://warontherocks.com/2019/06/is-the-air-force-serious-about-intelligence-surveillance-and-reconnaissance.

U.S. spending on intelligence gathering

The U.S. spends enormous sums of money on intelligence, exceeding the entire military budgets of wealthy nations. For comparison, the U.K., with the fifth largest economy in the world, spent roughly $45 billion on its military in 2018.

The U.S. possesses an enormous intelligence footprint that allows it to detect plots forming against the homeland even in remote regions of the world, identify and locate terrorist leaders, and strike even in areas where it has no local military presence. Intelligence is collected through satellite imagery, drone technology, cooperation from on-the-ground intelligence assets, and sometimes through covert U.S. special forces personnel. Signals intelligence, the collection of electronic communications, is an area where the U.S. excels—it has proven valuable in disrupting terrorist networks.19Matthew M. Aid, “All Glory is Fleeting: Sigint and the Fight Against International Terrorism,” Intelligence and National Security 18, no. 4, (2006): 72–120, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02684520310001688880. Over the years, the U.S. has also honed the ability to convert the vast amounts of information it collects into actionable intelligence that can guide targeted strikes.

U.S. capabilities are bolstered by cooperation on counterterrorism with more than 100 nations, whose own intelligence services act as a force multiplier.20Daniel L. Byman, “How Foreign Intelligence Services Help Keep America Safe,” Brookings, May 17, 2017, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/markaz/2017/05/17/how-foreign-intelligence-services-help-keep-america-safe. Allied governments can take aggressive measures to combat terrorists in their territory that the U.S. cannot, including arrest and question suspects, carry out enhanced interrogations, restrict travel, and exploit historical or ethnic ties to acquire information. During the Bush administration, the CIA deputy director of operations testified that nearly every successful capture or killing of a terrorist outside of Iraq was the result of at least some foreign cooperation.21Dana Priest, “Foreign Network at Front of CIA’s Terror Fight,” Washington Post, November 18, 2005, https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/11/17/AR2005111702070.html.

Once intelligence identifies a threat, if no other method exists to eliminate or disrupt it, unmanned aerial vehicles can track its location and launch strikes without putting U.S. lives at risk. Advances in drone technology—including better imaging and the ability to linger over an area longer—have made drones a potent counterterrorism tool. Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, a leading terrorist in Iraq, was located after the U.S. deployed dozens of drones to aerially scout the streets of Fallujah.22Alexander Farrow, “Drone Warfare as a Military Instrument of Counterterrorism Strategy,” Air & Space Power Journal, https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/ASPJ_Spanish/Journals/Volume-28_Issue-4/2016_4_02_farrow_s_eng.pdf

The ability to launch strikes from a variety of platforms and long-range bombers that can traverse continents enables the U.S. to eliminate targets far from where it maintains a military presence. A successful bombing raid on 90 ISIS fighters in the Libyan desert in 2012, carried out by aircraft launched from Missouri, is one of many examples.23William Langewiesche, “An Extraordinarily Expensive Way to Fight ISIS,” Atlantic, July/August 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2018/07/william-langewiesche-b-2-stealth-bomber/561719/. Even the 2019 mission to kill ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in Syria featured strike forces that originated well outside the country.24Deb Riechmann and Aamer Madhani, “The Tip, the Raid, the Reveal: The Takedown of al-Baghdadi,” Associated Press, October 28, 2019, https://apnews.com/89e8716887514b95af5fea38d604ee30. Following al-Baghdadi’s death, Marine Gen. Kenneth F. McKenzie briefed reporters that the mission was neither contingent nor dependent on having troops in Syria: “The United States military has the capability to go almost anywhere and support ourselves, even at great distances, so that was not a limiting factor.”25Shawn Snow, “CENTCOM Commander Releases Video of Raid on Baghdadi Compound, Which Now Looks Like a ‘Parking Lot with Large Potholes,’” Military Times, October 30, 2019, https://www.militarytimes.com/news/your-military/2019/10/30/centcom-commander-releases-video-of-raid-on-baghdadi-compound-which-now-looks-like-a-parking-lot-with-large-potholes/.

Strikes are by no means a panacea to the problem of terrorism and by themselves cannot entirely eradicate terrorist organizations. But they offer an effective, tailored approach that can and should replace our current, overly-broad strategy that has proved too costly and counterproductive. Continually eliminating experienced and influential leaders within these groups does take a toll, disrupting operations and forcing the organization to spend more time surviving than plotting new attacks. The ability of the U.S. to both locate and kill terrorists anywhere in the world also means that there are no longer any “safe havens”—terrorists are always vulnerable to preventive or retaliatory strikes from the U.S.

Domestic security in the U.S. has also improved substantially since 9/11, as resources flowed to domestic intelligence gathering and law enforcement—both crucial to counterterrorism efforts.26Erik J. Dahl, “The Plots that Failed: Intelligence Lessons Learned from Unsuccessful Terrorist Attacks Against the United States,” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 34, no. 8 (2011): 621–648, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1057610X.2011.582628. Major post-9/11 efforts to address terrorism included greater coordination among intelligence agencies, more resources to defend the homeland, expanded domestic surveillance, tighter border and transportation security, and programs to protect critical infrastructure.27Steven E. Miller, “After the 9/11 Disaster: Washington’s Struggle to Improve Homeland Security,” Axess, no. 2. (February 28, 2003): 8–11, https://www.belfercenter.org/publication/after-911-disaster-washingtons-struggle-improve-homeland-security. These efforts have largely proved successful, with more than 80% of terrorist plots foiled before execution in 2002 to 2012, compared to only 32% in 1995 to 2001.28Kevin J. Strom, John S. Hollywood, and Mark Pope, “Terrorist Plots Against the United States,” RAND Homeland Security and Defense Center, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/working_papers/WR1100/WR1113/RAND_WR1113.pdf. As a result, “the U.S. is much safer post-9/11” and “particularly better at thwarting plots… there has been a migration away from terrorists even attempting catastrophic attacks.”29Strom, Hollywood, Pope, “Terrorist Plots.”

The U.S. has nothing left to win in Afghanistan—bring all U.S. forces home

With U.S. troops in Afghanistan fighting insurgents rather than anti-U.S. terrorists, the mission is disconnected from efforts to keep the U.S. safe. Instead, it locks the U.S. into a cycle of prolonged bloodletting against the Taliban, who do not seek to attack the U.S. beyond their borders.

According to senior U.S. military leaders, there are currently some 20 terror groups operating in Afghanistan—compared to two prior to the U.S. invasion.30General John W. Nicholson, “Statement for the Record by General John W. Nicholson Commander U.S. Forces Afghanistan Before the Senate Armed Services Committee on the Situation in Afghanistan,” United States Senate Committee on Armed Services, February 9, 2017, https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Nicholson_02-09-17.pdf. Regardless of how many years the U.S. remains in Afghanistan, military operations there will never completely vanquish them, as they will always be able to recruit from the disaffected among the broader Afghan population. The only proven way to defeat counterinsurgencies is through overwhelming violence and the use of punitive measures against civilians sympathetic to the insurgents, an approach that violates U.S. values and which the U.S. is rightly unwilling to employ.31Jacqueline L. Hazelton, “The ‘Hearts and Minds’ Fallacy: Violence, Coercion, and Success in Counterinsurgency Warfare,” International Security 42, no. 1 (Summer 2017): 80–113, https://www.belfercenter.org/publication/hearts-and-minds-fallacy-violence-coercion-and-success-counterinsurgency-warfare.

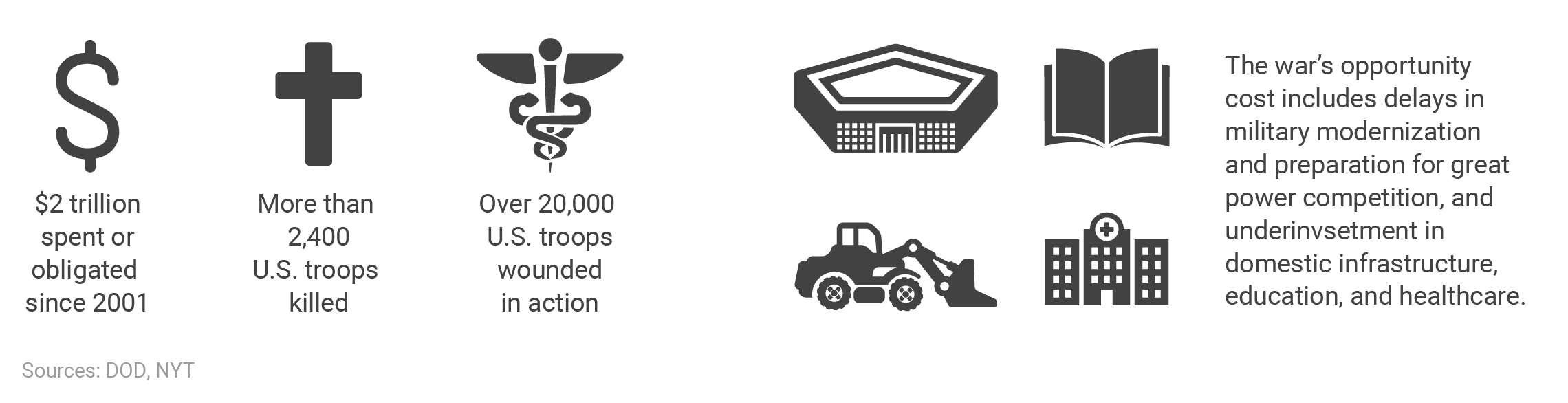

Costs of the 18-year war in Afghanistan

Afghanistan has cost precious U.S. lives and dollars. It has also come with an enormous opportunity cost, including military modernization, domestic infrastructure, healthcare, and education.

The Special Inspector General for Afghan Reconstruction (SIGAR) has chronicled the widespread, perpetual weakness and corruption of the Afghan government and Afghan forces. All evidence suggests conditions will not improve, whether the U.S. exits in six months, six years, or six decades. The only realistic policy at this point, then, is to end the mission according to the recently agreed-to timeline, even if the agreement falls apart.32“Agreement for Bringing Peace to Afghanistan Between the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan Which is Not Recognized by the United States as a State and is Known as the Taliban and the United States of America,” Department of State, February 29, 2020, https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Agreement-For-Bringing-Peace-to-Afghanistan-02.29.20.pdf. That means a full military withdrawal of all U.S. combat troops no later than April 2021.

The time between now and then should be spent working with our Afghan partners and NATO nations to transition to full Afghan control by the specified date. That would give the government of Afghanistan time to prepare for the date when their security will depend entirely on them.

Forcing Afghan leaders to take responsibility for their own survival will focus their minds like nothing else since the establishment of Afghanistan’s democratic government in 2004. It will give them motivation—for the first time—to strike a settlement with the Taliban that ends the war. It likely won’t be on terms Kabul would like and could well be messy, but that is unavoidable. The success of a deal favorable to Kabul is not a vital U.S. interest. The people of Afghanistan will determine their country’s future and govern their country as best they can. Because our security is not enhanced by our conventional military presence in Afghanistan, Americans will not be at any greater risk the day after withdrawal than they are today.

End overly broad nation building, and focus instead on core U.S. security

The response to 9/11 has been overly broad and more about counterinsurgency and nation building than effectively defending against anti-U.S. terrorism. A smarter, more effective, more affordable approach would rely far more on our unmatched intelligence capabilities than failed occupations that weaken the U.S. and distract from higher domestic and foreign priorities. If the U.S. identifies and locates terrorists that directly threaten U.S. territory, it can kill them anywhere in the world. There is no such thing as a “safe haven” outside of U.S. reach. Even unfriendly governments can be kept from harboring terrorists due to the U.S. ability to deter and punish them with direct retaliation should any attacks emerge from their countries.

Attempting to remake foreign nations in our image does not mitigate the threat of terrorism—if anything, it exacerbates the problem and foments radicalism. This policy weakens the U.S. and is doomed to failure. Indefinite U.S. occupations trigger insurgencies from aggrieved locals who would otherwise not pose a direct threat to the U.S. To remain in such conflicts is to knowingly extend unnecessary wars, diminish our security, deplete limited national resources, and bleed the troops.

U.S. security is best served by concluding open-ended military commitments, withdrawing our troops from ongoing counterinsurgency and nation building conflicts, and capitalizing on our remarkable ability to project power anywhere in the world to destroy terror threats to the U.S. It’s time to dispel with the “safe haven” myth once and for all and instead pursue an effective counterterrorism policy that enhances U.S. security.

Endnotes

- 1A variety of other authors have lamented how the “safe haven” myth fuels endless war. A partial list includes: Stephen M. Walt, “The ‘Safe Haven’ Myth,” Foreign Policy, August 18, 2009, https://foreignpolicy.com/2009/08/18/the-safe-haven-myth; John Mueller, “The ‘Safe Haven’ Myth,” The Nation, October 21, 2009, https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/safe-haven-myth/; Micah Zenko and Amelia Mae Wolf, “The Myth of the Terrorist Safe Haven,” Foreign Policy, January 26, 2016, https://foreignpolicy.com/2015/01/26/al-qaeda-islamic-state-myth-of-the-terrorist-safe-haven/; Paul R. Pillar, “The Safe Haven Notion,” National Interest, August 29, 2017, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/paul-pillar/the-safe-haven-notion-22099.

- 2“President Obama’s Remarks on New Strategy for Afghanistan and Pakistan,” New York Times, March 27, 2009, https://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/27/us/politics/27obama-text.html.

- 3The Associated Press, “Mattis in Kabul: We ‘look toward a victory in Afghanistan—not a military victory,’” Politico, March 13, 2018, https://www.politico.com/story/2018/03/13/jim-mattis-afghanistan-end-game-458325.

- 4National Commission on Terrorist Attacks, The 9/11 Commission Report (Washington, DC: Norton, 2004), https://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf.

- 59/11 Commission Report. p. 59

- 69/11 Commission Report. p. 149

- 79/11 Commission Report. p. 150

- 8Benjamin H. Friedman, “Sri Lanka Bombings Do Not Mean There’s an ISIS Worth Fighting,” USA Today, April 29, 2019, https://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2019/04/29/sri-lanka-bombings-dont-mean-isis-worth-fighting-editorials-debates/3622310002/.

- 9C-SPAN, “U.S. Strikes Against Terrorist Bases,” filmed August 1998 in Washington, DC, video, 7:55, https://www.c-span.org/video/?110184-1/us-strikes-terrorist-bases.

- 109/11 Commission Report. p. 140

- 119/11 Commission Report. p. 140

- 12Glenn Kessler, “Bill Clinton and the Missed Opportunities to Kill Osama bin Laden,” Washington Post, February 16, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/fact-checker/wp/2016/02/16/bill-clinton-and-the-missed-opportunities-to-kill-osama-bin-laden.

- 13“President Bush Discusses Progress in Afghanistan, Global War on Terror,” The White House, February 15, 2007, https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2007/02/20070215-1.html.

- 14Katie Bo Williams, “The U.S. Is Helping the Taliban Fight ISIS, CENTCOM’s Top General Says,” Defense One, March 10, 2020, https://www.defenseone.com/threats/2020/03/us-helping-taliban-fight-isis-top-general/163665/.

- 15“How Osama bin Laden Was Located and Killed,” New York Times, May 8, 2011, https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/interactive/2011/05/02/world/asia/abbottabad-map-of-where-osama-bin-laden-was-killed.html; Alex Ward, “‘Jackpot’: Inside the U.S. Military Raid to Kill ISIS Leader Baghdadi,” Vox, October 28, 2019, https://www.vox.com/2019/10/28/20936137/isis-baghdadi-raid-military-dog; Shane Harris, Anne Gearan, and Ellen Nakashima, “U.S. Targets Leader of Al-Qaeda in Yemen,” Washington Post, February 1, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/us-targets-leader-of-al-qaeda-in-yemen/2020/02/01/b4284f6a-450b-11ea-abff-5ab1ba98b405_story.html.

- 16Richard A. Best, Jr., “Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) Programs: Issues for Congress,” CRS Report for Congress, last modified February 22, 2005, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/intel/RL32508.pdf.

- 17Best, “Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance.”

- 18Robert Stiegel, “Is the Air Force Serious About Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance?” War on the Rocks, June 25, 2019, https://warontherocks.com/2019/06/is-the-air-force-serious-about-intelligence-surveillance-and-reconnaissance.

- 19Matthew M. Aid, “All Glory is Fleeting: Sigint and the Fight Against International Terrorism,” Intelligence and National Security 18, no. 4, (2006): 72–120, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02684520310001688880.

- 20Daniel L. Byman, “How Foreign Intelligence Services Help Keep America Safe,” Brookings, May 17, 2017, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/markaz/2017/05/17/how-foreign-intelligence-services-help-keep-america-safe.

- 21Dana Priest, “Foreign Network at Front of CIA’s Terror Fight,” Washington Post, November 18, 2005, https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/11/17/AR2005111702070.html.

- 22Alexander Farrow, “Drone Warfare as a Military Instrument of Counterterrorism Strategy,” Air & Space Power Journal, https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/ASPJ_Spanish/Journals/Volume-28_Issue-4/2016_4_02_farrow_s_eng.pdf

- 23William Langewiesche, “An Extraordinarily Expensive Way to Fight ISIS,” Atlantic, July/August 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2018/07/william-langewiesche-b-2-stealth-bomber/561719/.

- 24Deb Riechmann and Aamer Madhani, “The Tip, the Raid, the Reveal: The Takedown of al-Baghdadi,” Associated Press, October 28, 2019, https://apnews.com/89e8716887514b95af5fea38d604ee30.

- 25Shawn Snow, “CENTCOM Commander Releases Video of Raid on Baghdadi Compound, Which Now Looks Like a ‘Parking Lot with Large Potholes,’” Military Times, October 30, 2019, https://www.militarytimes.com/news/your-military/2019/10/30/centcom-commander-releases-video-of-raid-on-baghdadi-compound-which-now-looks-like-a-parking-lot-with-large-potholes/.

- 26Erik J. Dahl, “The Plots that Failed: Intelligence Lessons Learned from Unsuccessful Terrorist Attacks Against the United States,” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 34, no. 8 (2011): 621–648, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1057610X.2011.582628.

- 27Steven E. Miller, “After the 9/11 Disaster: Washington’s Struggle to Improve Homeland Security,” Axess, no. 2. (February 28, 2003): 8–11, https://www.belfercenter.org/publication/after-911-disaster-washingtons-struggle-improve-homeland-security.

- 28Kevin J. Strom, John S. Hollywood, and Mark Pope, “Terrorist Plots Against the United States,” RAND Homeland Security and Defense Center, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/working_papers/WR1100/WR1113/RAND_WR1113.pdf.

- 29Strom, Hollywood, Pope, “Terrorist Plots.”

- 30General John W. Nicholson, “Statement for the Record by General John W. Nicholson Commander U.S. Forces Afghanistan Before the Senate Armed Services Committee on the Situation in Afghanistan,” United States Senate Committee on Armed Services, February 9, 2017, https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Nicholson_02-09-17.pdf.

- 31Jacqueline L. Hazelton, “The ‘Hearts and Minds’ Fallacy: Violence, Coercion, and Success in Counterinsurgency Warfare,” International Security 42, no. 1 (Summer 2017): 80–113, https://www.belfercenter.org/publication/hearts-and-minds-fallacy-violence-coercion-and-success-counterinsurgency-warfare.

- 32“Agreement for Bringing Peace to Afghanistan Between the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan Which is Not Recognized by the United States as a State and is Known as the Taliban and the United States of America,” Department of State, February 29, 2020, https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Agreement-For-Bringing-Peace-to-Afghanistan-02.29.20.pdf.

Events on Counterterrorism