Key points

- A common argument for the United States to remain in the Middle East is that it needs to counter Chinese expansionism. The U.S. is embroiled in a new cold war, this line of thinking goes, and if it withdraws from the Middle East, Beijing will fill the power vacuum and expand its influence.

- This fundamentally misreads China’s modest aims in the region, which have more to do with hedging against U.S. threats to Chinese oil access.

- Unlike the Soviet Union, which was proximate to the Middle East, China lacks the military wherewithal to threaten the region.

- And whereas it was very plausible that the Soviet Union could have captured and weaponized Middle Eastern oil production, China almost certainly could not capture the oil, and even if it did, couldn’t withhold it from the global market.

- In the Middle East, the United States faces less of a military and economic threat from China than it did from the Soviet Union. It should respond by finally withdrawing from the region.

The case for the United States staying in the Middle East is weak, despite U.S. forces having been mired in the region for decades. Some 43,000 U.S. troops are currently stationed there, which includes roughly 34,000 troops permanently based in the region plus additional forces surged there since the October 7, 2023 terrorist attack on Israel.1Lolita C. Baldor and Tara Copp, “How Many US Troops Are in the Middle East?,” Associated Press, September 19, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/israel-hezbollah-us-military-ships-aircraft-3ef96cbdf87238de559e84e28573f611. The U.S. has military facilities in at least 10 Middle Eastern countries, with significant personnel based in Kuwait (13,500 troops), Qatar (8,000), and Bahrain (5,000). Bahrain also hosts the U.S. Navy’s Fifth Fleet.2“U.S. Security Cooperation with Kuwait,” United States Department of State, January 20, 2025, https://www.state.gov/u-s-security-cooperation-with-kuwait-2/; Jonathan Masters and Will Merrow, “U.S. Forces in the Middle East: Mapping the Military Presence,” Council on Foreign Relations, March 28, 2025, https://www.cfr.org/article/us-forces-middle-east-mapping-military-presence; Seth G. Jones, U.S. Defense Posture in the Middle East, 1st ed., CSIS Reports (Blue Ridge Summit: CSIS, 2022). Additionally, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Jordan each host roughly 2,500–3,500 U.S. soldiers, while another few thousand are deployed in Syria and Iraq.3Jones, U.S. Defense Posture in the Middle East, 13; Lolita Baldor and Tara Copp, “Pentagon Says It Doubled the Number of US Troops in Syria Before Assad’s Fall,” Associated Press, December 19, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/syria-us-troops-assad-tice-israel-35ac28d9c95a568828986da011bc02f1.

One of the most common objections to extricating the U.S. from the Middle East is that it will leave a “power vacuum” that China will fill.4“U.S. ‘Will Not Walk Away’ from Middle East: Biden at Saudi Summit,” Al Jazeera, July 16, 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/7/16/biden-lays-out-middle-east-strategy-at-saudi-arabia-summit. Proponents of this argument view China’s increased involvement in the region with suspicion, worrying that where economic interests go, military power will surely follow, with one U.S. general recently calling the Middle East “fertile ground” for strategic competition.5Jim Garamone, “General Says Middle East is a Theater for Strategic Competition,” U.S. Department of Defense, October 4, 2023, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3548607/general-says-middle-east-is-a-theater-for-strategic-competition/.Some contend that the United States must not only retain its bases and troop deployments but deepen its commitments to the region to outmaneuver China. For example, one of the purported “benefits” of the Saudi-Israeli normalization deal, which would have formalized U.S. defense commitments to Saudi Arabia and Israel, is that it would counter Chinese influence6Ghulam Ali and Peng Nian, “The China Factor in US-Saudi Talks for a Defense Pact,” Middle East Policy 32, no. 1 (2025): 90–103, https://doi.org/10.1111/mepo.12806; William Walldorf, “Just Stay out: Rejecting the Saudi-Israeli ‘Grand Bargain,’” Defense Priorities, November 26, 2024, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/just-stay-out-rejecting-the-saudi-israeli-grand-bargain/..

Such thinking reflects a larger framing of global competition between the two powers that some have dubbed a new cold war. They advocate that the U.S. adopt a policy of containment to systematically counter Chinese influence in every sphere—economic, diplomatic, and military—similar to how the U.S. reacted to the Soviets.7Condoleezza Rice, “The Perils of Isolationism,” Foreign Affairs, August 20, 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/perils-isolationism-condoleezza-rice. But that fundamentally misreads both the Cold War and the present situation. A rigorous understanding of how the Cold War played out in the Middle East suggests just the opposite: the U.S. can do less, perhaps radically less, than what was ever required to counter the Soviets in the region.

During the Cold War, the U.S. military presence in the Middle East was practically nonexistent.8Salim Yaqub, “The United States and the Persian Gulf: 1941 to the Present,” in Crude Strategy: Rethinking the U.S. Military Commitment to Defend Persian Gulf Oil, Edited by Charles L. Glaser and Rosemary A. Kelanic (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2016), 25. Instead of deploying sizable forces, the U.S. contained the Soviet Union by relying on regional proxies and issuing direct threats in the few instances when Soviet intervention seemed imminent, such as during the 1946 Iran crisis; the 1973 Yom Kippur War, when the U.S. briefly heightened the DEFCON level; and the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. That strategy—using partners to keep the Soviets out and only threatening to intervene directly if they go in directly—successfully deterred Soviet aggression in the much harsher threat environment of the Cold War when the Soviets held the upper hand in the region.

Baseline U.S. involvement in the Middle East today so exceeds anything the U.S. did during the Cold War that replicating the policies of that era would entail a massive drawdown. It stands to reason that if the current threat to the region from China is even lower, the U.S. should be able to do even less than it did against the Soviets. This raises the question: how does the Cold War-era Soviet threat compare to contemporary and future threats from China? And what consequences does that have for U.S. strategy and force posture?

The regional situation is practically a role reversal from the Cold War: the U.S. by far has the upper hand against China—leaving Washington with nothing to fear from Beijing’s involvement. Consequently, the U.S. could withdraw its forces without losing ground in its global competition with China. In fact, the U.S. would gain ground by finally freeing itself from misguided commitments that shackle rather than bolster its power.

This paper briefly outlines China’s growing involvement in the Middle East and considers the crucial differences with the Cold War case. It concludes that a retrenchment from the Middle East ultimately makes the most strategic sense for the United States.

Enter China

Without question, Chinese influence in the Middle East has grown significantly over the past few decades. In part, that reflects the unusually low baseline at which it started. China’s historic Silk Road trade ties with the Middle East tapered off substantially more than 500 years ago, leaving Chinese interaction with the region nearly nonexistent well into the mid-twentieth century. China’s revolutionary communist regime, from its assumption of power in 1949 through the death of its original leader Mao Zedong in 1976, eschewed international trade in favor of autarky as its main strategy for economic development. There was little trade to speak of—even in oil because China’s modest domestic production was enough to meet its similarly modest petroleum demand until the early 1990s.

China’s political, diplomatic, and economic policies to engage the Middle East today—which have Washington so concerned—emerged after the Cold War and have notably intensified in the past decade. China has become a major economic player in the Middle East, nearly doubling its trade with the region in the span of five years, from $263 billion in 2017 to $507 billion in 2022.9Dale Aluf, “China’s Influence in the Middle East and Its Limitations,” Diplomat, February 16, 2024, https://thediplomat.com/2024/02/chinas-influence-in-the-middle-east-and-its-limitations/. Now the largest trading partner for most countries in the region, China has also become a crucial source of international investment, not only in energy resources but in broadening sectors such as tourism, technology, and AI.10Dalia Dassa Kaye, “America’s Role in a Post-America Middle East,” Washington Quarterly 45, no. 1 (Spring 2022): 11. Since 2005, China has spent over $314 billion in investment and construction projects in Middle East and North African (MENA) countries—and another $68 billion in neighboring Pakistan—compared to its total investment of $201 billion in the United States in the same period.11“China Global Investment Tracker,” American Enterprise Institute, accessed November 27, 2024, https://www.aei.org/china-global-investment-tracker/.

Diplomatically, China has made inroads as a mediator, brokering the March 2023 Saudi-Iran rapprochement. China has also admitted several MENA countries as participants in Beijing-led international forums, including BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, and it has convened new regional organizations, including the China-Gulf Cooperation Council Strategic Dialogue and the China Arab States Cooperation Forum.12Jonathan Fulton and Michael Schuman, “China’s Middle East Policy Shift from ‘Hedging’ to ‘Wedging,’” Atlantic Council, September 5, 2024, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/chinas-middle-east-policy-shift-from-hedging-to-wedging/. At the same time, China has frustrated U.S. efforts to isolate Iran by purchasing some 90 percent of Iranian oil exports, despite Western sanctions.13Keith Bradsher, “China Buys Nearly All of Iran’s Oil Exports, but Has Options if Israel Attacks,” New York Times, October 4, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/10/04/business/iran-oil-sales-china.html; K. Oanh Ha et al., “The Shadowy Fleet of Tankers Moving Iranian Oil to China,” BNN Bloomberg, November 20, 2024, https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/investing/2024/11/20/the-shadowy-fleet-of-tankers-moving-iranian-oil-to-china/.

Military contacts have also increased. In recent years, China has conducted joint military exercises with local actors, including Iran and the UAE. 14 Takahashi Kosuke, “China and UAE to Conduct First Joint Fighter Jet Drill in August,” Diplomat, August 2, 2023, https://thediplomat.com/2023/08/china-and-uae-to-conduct-first-joint-fighter-jet-drill-in-august/; Stephanie L. Freid, “China-Russia-Iran Maritime Drills Send Signal to West,” Voice of America, March 15, 2024, https://www.voanews.com/a/china-russia-iran-maritime-drills-send-signal-to-west/7529934.html.Chinese arms exports to Middle Eastern countries have grown by 80 percent over the past decade, though total Chinese arms sales remain small compared to the U.S., which supplies 10 times more materiel to the region than China does.15Peter W. Singer, “How China Is Winning the Middle East,” Defense One, January 19, 2024, https://www.defenseone.com/ideas/2024/01/how-china-winning-middle-east/393483/; Walldorf, “Just Stay Out.”

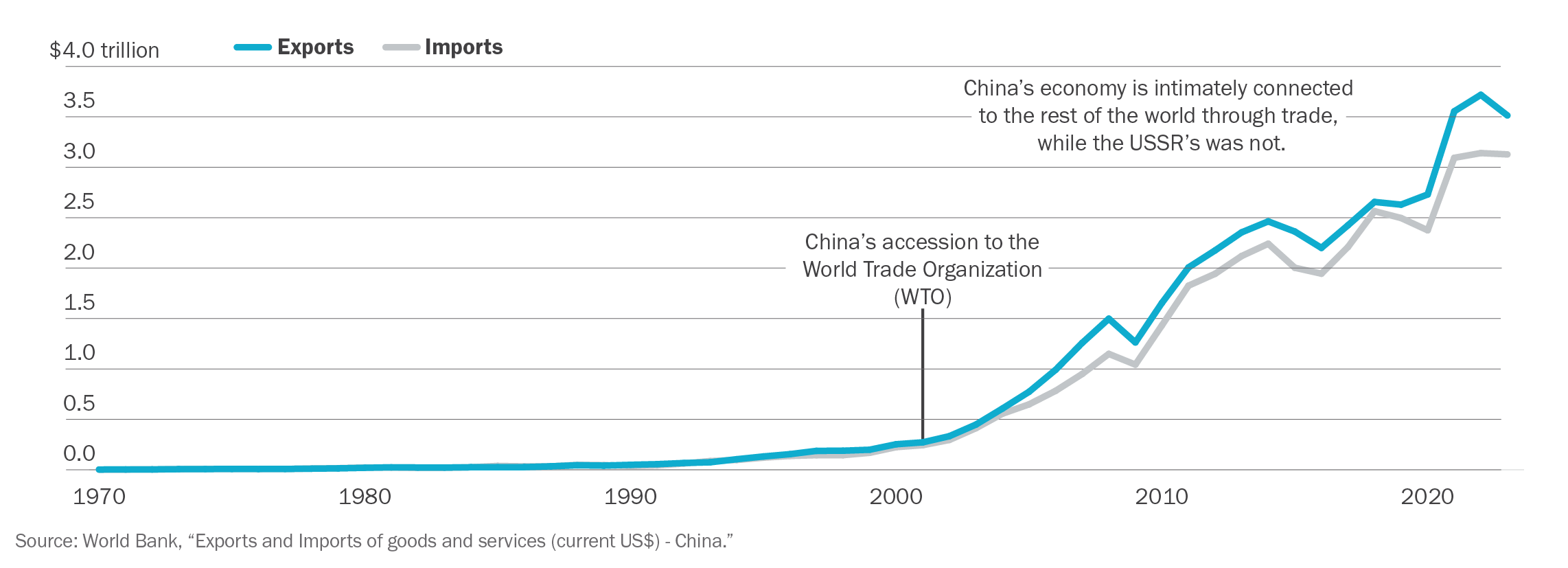

Chinese imports and exports over time

China regularly shows off its military inventory at regional airshows, even flying its Y-20 long-range transport aircraft and six J-10 performance jets over the Pyramids of Giza in August 2024, mere weeks after Egypt reportedly inked a deal to buy the 4.5 generation J-10 fighters.16Zhao Ziwen, “China’s Y-20 Transport Plane Goes to Egypt on Mideast Military Influence Mission,” South China Morning Post, August 27, 2024, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/military/article/3276101/chinas-y-20-transport-plane-heads-egypt-mideast-military-influence-mission; Seong Hyeon Choi, “Egypt Rumoured to Buy Chinese J-10C Jets as Middle East Looks Beyond U.S. Weapons,” South China Morning Post, September 21, 2024, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/military/article/3279387/egypt-rumoured-buy-chinese-j-10c-jets-middle-east-looks-beyond-us-weapons. Among the advantages of buying military hardware from China is that it allows countries like Egypt to get around Western restrictions on selling higher-technology platforms.17Ahmed Aboudouh, “Egypt’s Purchase of a Chinese Fighter Jet is a Reminder Cold War Tactics Are Back in the Middle East,” Chatham House, October 18, 2024, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2024/10/egypts-purchase-chinese-fighter-jet-reminder-cold-war-tactics-are-back-middle-east; Jennifer Kavanagh and Frederic Wehrey, “The Multialigned Middle East,” Foreign Affairs, July 17, 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/multialigned-middle-east-china-influence. Local regimes, faced with the dilemma of resisting U.S. regional dominance while guarding against the potential for U.S. abandonment, have welcomed China’s overtures, not least because China has been far less critical of their internal political systems and human rights records than Washington.18Jon B. Alterman, “The ‘China Model’ in the Middle East,” Survival, 66 (2), https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2024.2332062.

In 2017, China also established its first—and only—overseas military base in Djibouti to support anti-piracy missions around the Gulf of Aden. Initially, some worried the facility’s construction would herald a new era of Chinese base building in the Indian Ocean and Middle East, but such overwrought fears have not come to pass. The base is tiny and perhaps best described as sleepy, with nearly five years elapsing between its opening and when the first Chinese naval vessel docked there for resupply. So far, activities at the base seem to consist of spying on neighboring U.S. military facilities and lasing U.S. pilots, presumably out of boredom. The base houses a single battalion of about 400 marines but no aircraft, which severely limits the expeditionary value of those forces. China has also maintained a continuous naval presence in the Gulf of Aden since 2008, but only about three to four ships on average operate there.19“Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2024,” U.S. Department of Defense, https://media.defense.gov/2024/Dec/18/2003615520/-1/-1/0/MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA-2024.PDF, 57, 90, 143.

The above catalogue of Chinese engagement appears to frighten U.S. policymakers. They fear that that increased Chinese interests in the Middle East will naturally prompt greater Chinese military involvement there, which will undermine some key U.S. interest. But both of these assumptions appear dubious. China today poses nowhere near the threat to U.S. interests in the Middle East that the USSR did during the Cold War.

Two crucial differences between then and now should temper fears in Washington.

First, the Chinese military threat in the Middle East pales in comparison to the Soviet one by virtue of the design of the Chinese military and China’s distance from the region and consequent lower stakes in it. Second, the role of China in the oil market is completely different from the role of the USSR, making it impossible for Beijing to threaten the harm to the U.S. economy that the Soviets could.

Difference #1: The Chinese military threat pales in comparison to the Soviets

During the Cold War, the strategic value of the Middle East to the United States chiefly derived from its vast oil reserves, which were viewed as especially important to wealth and security in the non-communist “free world.” Thus the chief U.S. objective in the region was to ensure that the Soviets could not take over Middle East oil production and withhold it from the West. Two particular threats loomed: acute denial in wartime and chronic denial in peacetime.

First, the U.S. believed that NATO needed access to Middle East oil to win a protracted conventional war against the Soviets along the European Central Front—and it worried that the USSR would attempt acute denial by invading the Middle East in conjunction with an attack on Western Europe.20Michael Joseph Cohen, Fighting World War Three from the Middle East: Allied Contingency Plans, 1945–1954 (Portland, Ore.: Frank Cass, 1997), 29–32, http://discovery.lib.harvard.edu/?itemid=%7Clibrary/m/aleph%7C007421068. Joseph A. Yager and Eleanor B. Steinberg, Energy and U.S. Foreign Policy (Cambridge, Mass.: Ballinger, 1975), 326–327. Those fears first arose at the dawn of the Cold War in the late 1940s and continued well into the 1970s. Militaries lacking oil have no chance of winning wars, and NATO planners believed Mideast oil would be crucial for eventually defeating the Soviets in Europe. But policymakers saw little likelihood of holding the region in the short term against a Red Army that was widely viewed as conventionally superior. The Soviets were expected to overrun the Middle East in as little as one or two months.21Cohen, Fighting World War Three, 29–32. Strategy therefore focused on stiffening resistance to the Soviets to help keep some supplies open, like in Saudi Arabia and elsewhere, until these oilfields could eventually be recaptured.22Rosemary A. Kelanic, Black Gold and Blackmail: Oil and Great Power Politics (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2020), 135–40. Plans also secretly called for the United States and Britain to destroy the region’s oil industry before Soviet troops could arrive, thus rendering it useless to the Red Army’s war.23Michael Peck, “Revealed: How America and Britain Planned to Destroy the Middle East’s Oil,” National Interest, June 24, 2016, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/revealed-how-america-britain-planned-destroy-the-middle-16701.

Second, Washington worried about chronic economic “strangulation” of the West if the Soviets or their proxies controlled Middle East oil and refused to sell it, thus causing the West to pay exorbitant prices that would slow its relative growth and, over time, sap its economic and military potential. Especially in the late 1970s and early 1980s, U.S. policymakers feared that the economic problems caused by high energy prices—such as inflation, unemployment, and sluggish growth—might “impair the ability of the U.S. and its allies to marshal the resources necessary for the defense of the non-communist world.”24“Memorandum from the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Economic and Technology Affairs (Frost) to the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy (Komer), July 16, 1980,” in Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976, Volume XXXVII, Energy Crisis, 1974–1980, accessed November 27, 2024, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76v37/d279. The large-scale wealth transfer away from the net-importing countries of NATO toward net-exporters—including the Soviet Union itself—would “reduc[e] the sum of resources available to meet the Soviet challenge” with the result that “the West’s defense effort falls short of what it should be” over the long term.25“Memorandum from the Deputy Assistant Secretary…”

These threats were all too real due to Soviet proximity, power, and proclivity to expand its influence towards the Persian Gulf. The U.S. and Britain, the Western powers with greatest influence in the Middle East, were geographically disadvantaged compared to the USSR, which abutted the region and shared a particularly long, 1,250-mile border with Iran.26Louise Fawcett, Iran and the Cold War: The Azerbaijan Crisis of 1946 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 83. That common border meant two things: first, the Soviets viewed Iran as a buffer state whose security was inextricably linked with their own. Moscow had a strong interest in keeping out Western powers, which they feared could use the country as a base to attack Soviet industries and oilfields around Baku, situated a mere 100 miles from the Iranian border.27Daniel Yergin, Shattered Peace: The Origins of the Cold War (New York: Penguin Books, 1990), 181. Second, proximity also meant it was much easier for the Soviets to operate militarily in the region than it was for the British or the Americans, who had to project power across vast oceans and land masses.

China, the USSR, and the Middle East

Furthermore, the Soviet Union had longstanding territorial ambitions in the region and a robust track record of expansion—particularly in Iran. In the late nineteenth century, the Russian Empire conquered vast swaths of territory from Iran and the Ottoman Empire and competed with Britain for regional supremacy in a contest known as the Great Game, until domestic troubles, combined with defeat in the 1905 Russo-Japanese war, waylaid further conquest.28William L. Cleveland, A History of the Modern Middle East, 3rd ed. (Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 2004), 113–115. Fawcett, Iran and the Cold War, 83. In 1907, Russia and Britain carved Iran into spheres of influence, with Russia claiming the north and Britain claiming the southeast. But Russia continued to meddle beyond its zone and pressured Iran to accept a 1921 “Treaty of Friendship” that granted Russia the prerogative to occupy Iran if threatened by an outside power—essentially a ready-made pretext for future incursions.29“TREATY OF FRIENDSHIP BETWEEN PERSIA AND THE RUSSIAN SOCIALIST FEDERAL SOVIET REPUBLIC, SIGNED AT MOSCOW, FEBRUARY 26, 1921 | CIA FOIA (Foia.Cia.Gov),” accessed November 5, 2024, https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/document/cia-rdp84b00049r000701920007-1; Kristen Blake, The US-Soviet Confrontation in Iran, 1945-1962: A Case in the Annals of the Cold War (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 2009), 10.

Soviet expansionism intensified through World War II. In secret talks with Germany in 1940, the Soviet Union demanded a sphere of influence in the Persian Gulf as a condition of the Nazi-Soviet alliance.30Bruce R. Kuniholm, The Origins of the Cold War in the Near East: Great Power Conflict and Diplomacy in Iran, Turkey, and Greece (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1980), 138. After Germany broke the alliance and attacked the USSR in June 1941, some 40,000 Soviet troops invaded Iran to root out German sympathizers, in conjunction with a smaller British campaign in the south.31Kuniholm, 140. Iran soon became the most vital conduit for Allied military assistance, including Lend-Lease aid, to the USSR.

Soviet refusal to withdraw from Iran following World War II was decisive in convincing Washington that Moscow was “highly aggressive” and provoked the first major confrontation of the Cold War.32Ashley Jackson, Persian Gulf Command: A History of the Second World War in Iran and Iraq, 1st ed. (New York: Yale University Press, 2018), 355. By late 1945, troubling developments suggested the USSR intended to remain in Iran despite its pledge to vacate within six months after the war. Captured German documents read by U.S. policymakers revealed the Soviets’ secret desire to dominate the Persian Gulf.33Kuniholm, Origins, 293–294. The Soviets were also fomenting uprisings in Iran, as they had done so effectively to cement influence in Eastern Europe.

By March 1946, Soviet forces in Iran had not only overstayed the deadline but been reinforced, confirming U.S. fears. U.S. intelligence detected heavy troop movements toward Tehran, signaling a major military operation might be imminent. President Harry S. Truman warned his advisors that the U.S. and the Soviet Union were on the verge of war.34Kuniholm, Origins, 319–325. The Truman administration confronted Stalin by publicizing the Soviet troop movements and threatening an American response unless the Soviets left Iran immediately. Caught red-handed, the Soviets backed down, hastily concluding a withdrawal agreement with the Iranian government to save face while the Red Army was recalled.

The 1945–46 Iran crisis convinced Washington that the Soviets sought to dominate the Middle East and dramatically shaped U.S. policy moving forward. U.S. leaders were willing to risk war because Soviet control of Iran would place that country’s oilfields in hostile hands and jeopardize U.S. interests throughout the Persian Gulf.35Yergin, Shattered Peace, 181 The episode inspired the Truman Doctrine, which provided military assistance to democratic regimes threatened by communism, including $400 million in aid to Greece and Turkey.36Kuniholm, Origins, 411–414.

Due to resource constraints generated by the need to keep U.S. troops in Europe and Asia, the U.S. used proxies to deter Soviet expansion in the Middle East in lieu of direct deployments. From the late 1940s until the late 1960s, Britain played the primary role. British military power, despite its severe limitations, kept the Soviets at bay for two decades. Yet fiscal struggles finally impelled the British to withdraw in 1971, causing the U.S. to rely on regional powers, Iran and Saudi Arabia, to contain the Soviet Union. That policy, known as the “Twin Pillars” strategy, bolstered both countries’ capabilities to resist Soviet power through massive U.S. arms sales, particularly to Iran. President Richard Nixon, who had a strong rapport with the Shah, increased military sales to Iran sevenfold, from $94.9 million to $682.8 million over the course of his presidency.37Roham Alvandi, Nixon, Kissinger, and the Shah: The United States and Iran in the Cold War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 64.

The Soviet threat to Mideast oil grew substantially worse in 1979, when the ouster of the Shah collapsed the primary U.S. pillar and the Soviets invaded neighboring Afghanistan, potentially encircling Iran. Moscow’s move brought fears that a new round of Soviet aggression was afoot, giving the Soviets an opportunity to exploit Iranian chaos, dominate the Persian Gulf, and menace the Strait of Hormuz, a crucial chokepoint for oil shipping. The direct Soviet threat prompted President Jimmy Carter to threaten direct U.S. military action, warning in his 1980 State of the Union address, “An attempt by any outside force to gain control of the Persian Gulf region will be regarded as an assault on the vital interests of the United States of America, and such an assault will be repelled by any means necessary, including military force.”38“January 23, 1980: State of the Union Address,” UVA Miller Center, October 20, 2016, https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches/january-23-1980-state-union-address. That statement, now known as the Carter Doctrine, marked the first explicit U.S. pledge to defend the flow of Persian Gulf oil.

Soviet actions prompted Carter to ask Congress to massively increase defense spending to build the forces necessary to enact his pledge. Even famously dovish officials, including Senator George McGovern, the antiwar former presidential candidate, supported major increases.39Victor McFarland, Oil Powers: A History of the U.S.-Saudi Alliance (New York: Columbia University Press, 2020), 231. In the interim, the U.S. military drew up plans for a Rapid Deployment Force that could quickly respond to Soviet activities and laid the groundwork to establish CENTCOM in 1983, the military command now responsible for the region.

Despite the initial alarm, however, U.S. force levels remained modest.40Yaqub, “The United States and the Persian Gulf,” 35–37. Washington continued to rely on others to balance threats in the Middle East, this time by focusing on Iraq, which presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush misguidedly attempted to woo into the U.S. camp throughout the 1980s.41Bruce W. Jentleson, With Friends Like These: Reagan, Bush, and Saddam, 1982–1990 (New York: Norton, 1994). During the 1980–1988 Iran-Iraq War, the Reagan administration also secretly shipped arms to Iran in exchange for the release of U.S. hostages held by the Islamic regime, part of a convoluted scheme known as the Iran-Contra Affair. Thus the U.S. effectively armed both sides of the devastating eight-year-long conflict.

In 1981, Iraq began to attack Iranian oil tankers operating in the Persian Gulf, kicking off the Tanker War. While modest at first, Iraqi attacks on shipping escalated in 1984, provoking Iran to retaliate by targeting Iraqi oil tankers. Yet the Tanker War had only negligible effects on the global oil supply. Shipping volumes in the Persian Gulf were so massive that less than 1 percent of all tanker traffic in the Persian Gulf actually came under attack.42Eugene Gholz and Daryl G. Press, “Protecting ‘the Prize’,” Security Studies, vol. 19 (2010): 468. Very few tankers were totaled, let alone sunk.43“Tanker War,” Strauss Center for International Security and Law, last modified August 2008, https://www.strausscenter.org/strait-of-hormuz-tanker-war/. Oil production by the belligerents remained steady and oil prices actually decreased slightly during the conflict.44Gholz and Press, “Protecting ‘the Prize’,” 468.

Perhaps because the market adapted so smoothly, the United States stayed out of the Tanker War for six years, only intervening to reflag and escort Kuwaiti tankers in 1987 because the Soviets offered to do so first. Though the reflagging mission was ostensibly to protect oil, it was in fact symbolic, motivated by a political desire to steal influence away from the Soviets. It had only superfluous effects on the global oil market, which weathered the crisis ably.

Meanwhile, far from serving as a launching pad, the Afghanistan war drained Soviet resources, contributing to the end of the Cold War and the ultimate dissolution of the USSR itself.

The contemporary era of massive U.S. deployments did not begin until 1990–1991, when Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait prompted the U.S. to fight the Persian Gulf War, after which U.S. forces never fully left. By then, the Soviet Union had ceased to exist, removing any real check on the expanded U.S. military footprint.

The lack of a Chinese military threat

In stark contrast to the Soviet Union, China cannot militarily threaten the Middle East today and will be unable to do so for decades—if ever. Long distances separate China from the Middle East, historically leaving the region “always on the periphery of the Chinese world order.”45Yitzhak Shichor, The Middle East in China’s Foreign Policy, 1949–1977, International Studies (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979), 6, http://discovery.lib.harvard.edu/?itemid=%7Clibrary/m/aleph%7C000852451. As a result, China has no history of aggression analogous to the Soviets nor any unresolved territorial claims in the region. Rather, the country has priorities that are much more immediate in both the temporal and locational sense of the word.

The Chinese military has been purpose-built for an entirely different mission—a cross-strait contingency with Taiwan—and those forces simply cannot project power over long distances, let alone into the Middle East. The forces necessary to invade and conquer Taiwan, while resisting potential intervention by U.S. forces stationed in Asia, differ substantially from those needed for global reach. Much of China’s military development has been geared towards establishing air superiority over Taiwan, building lift capacity to reach the island, and enhancing A2/AD sensor and missile capabilities to make it very costly for U.S. forces to intervene. These priorities are quite costly and will not disappear from the defense budget anytime soon.

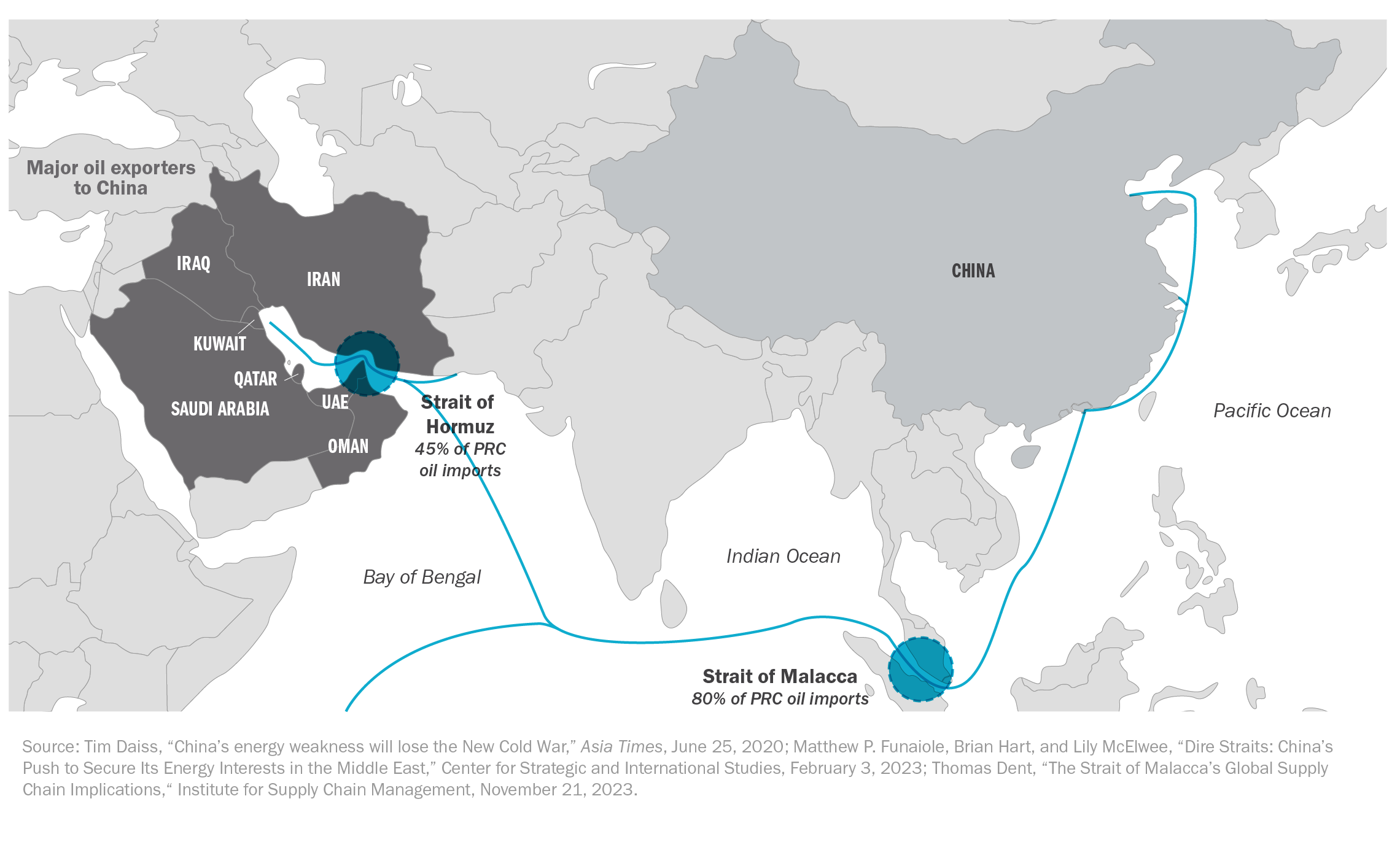

Beijing’s naval modernization—which has produced undue anxiety in Washington—also reflects its larger focus on Taiwan. That is even true of its efforts to establish a blue water navy capable of operating beyond the First Island Chain into the Indian Ocean and towards the Persian Gulf. Such measures can be straightforwardly interpreted as preparations to deal with the U.S. naval threat to Chinese oil imports should war break out over Taiwan.46Sean Mirksi, “Stranglehold: The Context, Conduct, and Consequences of an American Naval Blockade of China,” Journal of Strategic Studies 36, no. 3 (2013): 385–421; Fiona S. Cunningham, “The Maritime Rung on the Escalation Ladder: Naval Blockades in a U.S.-China Conflict,” Security Studies 29, no. 4 (2020): 730–768.

Chinese military strategists have worried for years about the Malacca Dilemma—the fact that some 63 percent of Chinese oil imports travel through the maritime chokepoint at the Strait of Malacca, potentially rendering them vulnerable to a U.S. naval blockade.47“Military and Security Developments…” 144 Were Chinese oil imports not so reliant on seaborne trade that is vulnerable to U.S. naval predominance, it is dubious whether China would expand its naval operations along that route at all. Quite simply, and contra the Cold War case, U.S. dominance is what creates the security dilemma along naval routes toward the Middle East, prompting Chinese moves to protect its energy supplies, which in turn raise U.S. fears that Chinese motives are aggressive.

The Malacca dilemma

Aims of the naval modernization aside, there is no question that China remains well behind the United States in projecting power into the Indian Ocean and Persian Gulf—perhaps hopelessly so. While its sheer quantity of ships narrowly outnumbers the U.S. fleet, its navy is qualitatively inferior and composed for local defense, lacking the aircraft carriers and support ships necessary for blue water missions.48Mike Sweeney, “Challenges to Chinese Blue-Water Operations,” Defense Priorities, May 1, 2024, 14–16, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/challenges-to-chinese-blue-water-operations/. Nor does China possess anything approaching the basing network it would need to operate far from home, particularly in contested circumstances, where at-sea refueling and resupply are extremely difficult if not deadly.49Sweeney, 9–12.

Finally, even if the Chinese had the capabilities to take a more active military role in the Middle East, they seem totally uninterested in doing so, let alone acting in ways that would supplant the United States.50Dawn C. Murphy, China’s Rise in the Global South: The Middle East, Africa, and Beijing’s Alternative World Order (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2022), 32; Dalia Dassa Kaye, “America’s Role in a Post-America Middle East,” Washington Quarterly 45, no. 1 (Spring 2022): 11–12. Instead, Beijing seems happy to free-ride on Washington’s “security provision” (insofar as the U.S. presence actually stabilizes the region, which is debatable). For instance, they’ve refusing to join international efforts to combat Houthi attacks on Red Sea shipping, and notably the Houthis do not target Chinese vessels because they have no major grievances against the Chinese, who have avoided meddling in regional politics.51Dale Aluf, “China’s Influence in the Middle East and Its Limitations,” Diplomat, February 16, 2024, https://thediplomat.com/2024/02/chinas-influence-in-the-middle-east-and-its-limitations/. The Chinese seem to understand that U.S. involvement in the region has brought the United States much grief and are perfectly happy to avoid that fate.

Additionally, China seems to be pursuing a new energy security strategy to wean off of oil that will likely lessen the region’s importance to Beijing in the coming decades. Successful efforts to encourage the adoption of electric vehicles (EVs), which now account for half of new Chinese car sales, and construct a high-speed rail network have already allowed China to lessen its oil demand by 1.2 million barrels per day, with greater reductions to follow.52“Oil Demand for Fuels in China Has Reached a Plateau,” IEA, March 11, 2025, https://www.iea.org/commentaries/oil-demand-for-fuels-in-china-has-reached-a-plateau. Surprisingly, Chinese gasoline demand appears to have peaked between 2023–2025 and diesel consumption will do the same no later than 2027.53Erica Downs and Abhiram Rajendran, “China’s Slowing Oil Demand Growth is Likely to Persist and Could Impact Markets,” Center on Global Energy Policy, Columbia University, November 13, 2024, https://www.energypolicy.columbia.edu/chinas-slowing-oil-demand-growth-is-likely-to-persist-and-could-impact-markets/.

Difference #2: The economic context could hardly differ more

Not only could the Soviets intervene militarily in ways China cannot, but they also operated according to radically different economic precepts that made the potential use of the “oil weapon” against the West eminently plausible. As a self-sufficient communist country unmotivated by profits and detached from the U.S.-led global trading system, the USSR wastefully guzzled resources as a matter of course and viewed trade as a means of political coercion rather than economic development. Today’s China could not realistically eschew market imperatives the way the USSR could because its free-market economic system participates heavily in trade and relies on economic growth for political legitimacy.

It is hard to appreciate today just how radically different Soviet-style communism was, with its singular predisposition for economic irrationality and emphasis on military strength over wellbeing. Examples abound of Soviet inefficiency. This is a system that incentivized the production of egregiously heavy aircraft, unsellable in international markets, because it rewarded managers based on the cost of inputs used in manufacturing, not the performance of the planes.54Marshall I. Goldman, “Diffusion of Development: The Soviet Union,” American Economic Review 81, no. 2 (1991): 277. Soviet street cleaners wasted water spraying Moscow’s roads constantly, even when it rained.55Marshall Goldman and Steven Baral, “Soviet Energy Problems,” Harvard International Review 3, no. 5 (February 1981): 31. The Soviet economy also endured massive defense burdens. Some 87 percent of 18-year-old men were conscripted, and 15 percent or more of national income was diverted to the military—unthinkable numbers today.56Paul R. Gregory and Robert C. Stuart, Soviet Economic Structure and Performance, 4th ed. (New York: Harper & Row, 1990), 407–409. China’s defense expenditure in 2023 amounted to 1.7 percent of its GDP, whereas the U.S. defense burden was 3.4 percent.57“Military Expenditure (% of GDP),” World Bank Open Data, accessed April 3, 2025, https://data.worldbank.org.

Moreover, unlike today, there was no integrated world trading system during the Cold War that incorporated both NATO and Warsaw Pact countries, let alone a single global market for oil. Instead, international trade was split into rival East-West blocs that were not only highly detached from each other but also based on incompatible economic systems with radically different theoretical underpinnings.

Whereas in the West, relatively free trade existed between the United States and its capitalist allies under the auspices of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), no open trading system existed on the Soviet side. The Soviet-led bloc of socialist countries known as the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON) was a centrally planned system that operated through bilateral bartering agreements whose chief purpose was not to foster economic growth but to sustain and reproduce Soviet political dominance. It cultivated Eastern European economic dependence on the Soviet Union through trade subsidies—particularly in oil—which Moscow hoped would keep its buffer states pliant within the Soviet orbit. Far from promoting growth, COMECON was a net drain on the Soviet economy.58Randall W. Stone, Satellites and Commissars: Strategy and Conflict in the Politics of Soviet-Bloc Trade (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996), 5.

The USSR was highly trade averse for ideological reasons, with trade levels extremely low for a country at its level of development. Total exports in 1955 represented just 3 percent of Soviet gross national product (GNP). That number doubled to about 6.5 percent of GNP in 1976, which was still low in absolute terms. At its height in 1987, Soviet trade with all countries—including COMECON—amounted to no more than 8 percent of gross national product (GNP), compared to about 15 percent of U.S. GNP that year.59Gregory and Stuart, Soviet Economic Structure and Performance, 324–325, 342.

Although lack of trade between the Eastern and Western blocs was the norm, the USSR did export oil to the West in the 1970s–80s and oil sales comprised a major source of hard currency. But rather than maximize petroleum sales, the Soviets determined their export levels based on how much hard currency they needed for desired imports like technology and grain. They carefully minimized petroleum exports outside of COMECON to maintain self-sufficiency and avoid growing too dependent on the West.60Gregory and Stuart, Soviet Economic Structure and Performance, 332–333. That said, the Soviets did exploit high oil prices when possible. For example, despite publicly supporting the 1973 Arab oil embargo on the U.S., the Soviets privately violated it to benefit from the attending price shock. Designated as a “friendly” country under the embargo, the USSR surreptitiously purchased Persian Gulf oil and resold it to the West, earning an additional $700 million in hard currency from oil in 1973 compared to the prior year.61Marshall I. Goldman, “The Soviet Union,” Daedalus 104, no. 4 (1975): 138; Marshall I. Goldman, “The Soviet Energy Pipeline,” Current History 81, no. 477 (October 1, 1982): 312.

Altogether, there was good reason to expect Persian Gulf oil to disappear into the enormous black hole that was Soviet-style communism if the Soviets gained control of it. On one hand, the Soviet Union was a net-exporter that benefitted from high oil prices, which gave it an incentive to restrict access to Middle East oil. On the other hand, as communists, the Soviets also were not necessarily profit-motivated, and thus might withhold oil entirely to harm the U.S., even at the cost of forgoing significant oil income. After all, under the Soviet model of development, “the consumer generally [came] last.”62Marshall I. Goldman, “The Economy and the Consumer,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 38, no. 4 (April 1982): 24, https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.1982.11455721. Either way, economic relations with the West were essentially zero-sum because there was no real economic interdependence between the U.S. and Soviet blocs. That meant that the Soviets could damage Western economies without suffering boomerang damage themselves.

China would sell oil

By contrast, if China somehow took control over the disposition of Middle East oil, it would not be able to strategically withhold it. China is a consumer-oriented country whose regime’s legitimacy rests on continued economic growth. Even if they had some influence over the disposition of Middle East oil, they would need to sell it, either domestically or internationally, to maintain economic performance. Unlike the Soviets, China would not be able to absorb more oil than it needed and take the loss, because that would interfere with the political imperative of generating GDP growth that keeps the Chinese regime in power. They cannot afford to mimic Soviet levels of wastefulness, a lesson China learned from the 1980s Soviet economic collapse and reformed their system to avoid.63Yanjie Huang, “Ideology Strikes Back: China’s Lessons of the Soviet Collapse, 1992–2022,” Problems of Post-Communism 71, no. 6 (November 1, 2024): 579–591, https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2023.2301108.

Moreover, because China is connected to the global oil market, Chinese-controlled Middle Eastern oil would still be part of the global oil “bathtub” even if it was exclusively sold to China.64Charles L. Glaser and Rosemary A. Kelanic, “Getting Out of the Gulf,” Foreign Affairs, December 12, 2016, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/persian-gulf/2016-12-12/getting-out-gulf, 123. It would simply displace Chinese oil imports from other sources, which in turn could turn around and export that oil to global markets instead. Other countries might have to shift suppliers, but the overall size of the market would not be any smaller—it would just be re-arranged.

Finally, because it is integrated into the global trading system in a way the USSR never was, any moves China makes to hurt the United States economically would boomerang to hurt China, too. China might be willing to endure significant economic costs in pursuit of core national interests, but the point is that China would face costs the Soviet Union did not. Interdependence gives China a stake in the U.S. economy that the USSR never had, because the Soviet system operated independently from the West. Thus economics provide an additional source of moderation that was absent during the Cold War.

Policy implications: Why less is more

Primacists raise the specter of a new cold war with China to haunt the U.S. into maintaining—or even expanding—its role in the Middle East. But the Cold War comparison suggests that superpower competition between the United States and China in the Middle East need never reach the level that accompanied the U.S.-Soviet case. Cold War-era worries that an adversary could control the Middle East and use its oil resources to economically sabotage the United States and the wider free world simply do not apply to contemporary circumstances.

Whereas the Soviet military threat to Persian Gulf oil was serious and immediate, China cannot disrupt oil access militarily. In fact, it is Chinese oil imports that are threatened by U.S. naval predominance, not the other way around. Moreover, unlike the USSR, China follows market principles that make it highly unlikely it could deprive the West of oil even if Middle Eastern supplies somehow fell into Chinese hands. Chinese oil consumption is already “baked in” to the world market, so even if it somehow “locked up” its own present or future supplies, that would merely rearrange, rather than reduce, the oil available to markets outside of China. Moreover, the Chinese regime could not afford to sit on surplus oil it controlled, because doing so would be prohibitively costly for a regime whose domestic legitimacy hinges on maintaining broad prosperity.

In sum, Washington’s obsession with countering Beijing in the Middle East makes little sense. China does not meaningfully threaten U.S. interests in the region and likely never will. Misguided commitments there merely sap U.S. resources and tie down the U.S. military unnecessarily, while China, facing no such encumbrances, continues to rise. Rather than exploit a purported vacuum, China is more likely to view a U.S. exit with dismay, for it would signal that the United States has finally wised up about its strategic priorities—which don’t include the Middle East.

Endnotes

- 1Lolita C. Baldor and Tara Copp, “How Many US Troops Are in the Middle East?,” Associated Press, September 19, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/israel-hezbollah-us-military-ships-aircraft-3ef96cbdf87238de559e84e28573f611.

- 2“U.S. Security Cooperation with Kuwait,” United States Department of State, January 20, 2025, https://www.state.gov/u-s-security-cooperation-with-kuwait-2/; Jonathan Masters and Will Merrow, “U.S. Forces in the Middle East: Mapping the Military Presence,” Council on Foreign Relations, March 28, 2025, https://www.cfr.org/article/us-forces-middle-east-mapping-military-presence; Seth G. Jones, U.S. Defense Posture in the Middle East, 1st ed., CSIS Reports (Blue Ridge Summit: CSIS, 2022).

- 3Jones, U.S. Defense Posture in the Middle East, 13; Lolita Baldor and Tara Copp, “Pentagon Says It Doubled the Number of US Troops in Syria Before Assad’s Fall,” Associated Press, December 19, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/syria-us-troops-assad-tice-israel-35ac28d9c95a568828986da011bc02f1.

- 4“U.S. ‘Will Not Walk Away’ from Middle East: Biden at Saudi Summit,” Al Jazeera, July 16, 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/7/16/biden-lays-out-middle-east-strategy-at-saudi-arabia-summit.

- 5Jim Garamone, “General Says Middle East is a Theater for Strategic Competition,” U.S. Department of Defense, October 4, 2023, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3548607/general-says-middle-east-is-a-theater-for-strategic-competition/.

- 6Ghulam Ali and Peng Nian, “The China Factor in US-Saudi Talks for a Defense Pact,” Middle East Policy 32, no. 1 (2025): 90–103, https://doi.org/10.1111/mepo.12806; William Walldorf, “Just Stay out: Rejecting the Saudi-Israeli ‘Grand Bargain,’” Defense Priorities, November 26, 2024, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/just-stay-out-rejecting-the-saudi-israeli-grand-bargain/.

- 7Condoleezza Rice, “The Perils of Isolationism,” Foreign Affairs, August 20, 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/perils-isolationism-condoleezza-rice.

- 8Salim Yaqub, “The United States and the Persian Gulf: 1941 to the Present,” in Crude Strategy: Rethinking the U.S. Military Commitment to Defend Persian Gulf Oil, Edited by Charles L. Glaser and Rosemary A. Kelanic (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2016), 25.

- 9Dale Aluf, “China’s Influence in the Middle East and Its Limitations,” Diplomat, February 16, 2024, https://thediplomat.com/2024/02/chinas-influence-in-the-middle-east-and-its-limitations/.

- 10Dalia Dassa Kaye, “America’s Role in a Post-America Middle East,” Washington Quarterly 45, no. 1 (Spring 2022): 11.

- 11“China Global Investment Tracker,” American Enterprise Institute, accessed November 27, 2024, https://www.aei.org/china-global-investment-tracker/.

- 12Jonathan Fulton and Michael Schuman, “China’s Middle East Policy Shift from ‘Hedging’ to ‘Wedging,’” Atlantic Council, September 5, 2024, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/chinas-middle-east-policy-shift-from-hedging-to-wedging/.

- 13Keith Bradsher, “China Buys Nearly All of Iran’s Oil Exports, but Has Options if Israel Attacks,” New York Times, October 4, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/10/04/business/iran-oil-sales-china.html; K. Oanh Ha et al., “The Shadowy Fleet of Tankers Moving Iranian Oil to China,” BNN Bloomberg, November 20, 2024, https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/investing/2024/11/20/the-shadowy-fleet-of-tankers-moving-iranian-oil-to-china/.

- 14Takahashi Kosuke, “China and UAE to Conduct First Joint Fighter Jet Drill in August,” Diplomat, August 2, 2023, https://thediplomat.com/2023/08/china-and-uae-to-conduct-first-joint-fighter-jet-drill-in-august/; Stephanie L. Freid, “China-Russia-Iran Maritime Drills Send Signal to West,” Voice of America, March 15, 2024, https://www.voanews.com/a/china-russia-iran-maritime-drills-send-signal-to-west/7529934.html.

- 15Peter W. Singer, “How China Is Winning the Middle East,” Defense One, January 19, 2024, https://www.defenseone.com/ideas/2024/01/how-china-winning-middle-east/393483/; Walldorf, “Just Stay Out.”

- 16Zhao Ziwen, “China’s Y-20 Transport Plane Goes to Egypt on Mideast Military Influence Mission,” South China Morning Post, August 27, 2024, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/military/article/3276101/chinas-y-20-transport-plane-heads-egypt-mideast-military-influence-mission; Seong Hyeon Choi, “Egypt Rumoured to Buy Chinese J-10C Jets as Middle East Looks Beyond U.S. Weapons,” South China Morning Post, September 21, 2024, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/military/article/3279387/egypt-rumoured-buy-chinese-j-10c-jets-middle-east-looks-beyond-us-weapons.

- 17Ahmed Aboudouh, “Egypt’s Purchase of a Chinese Fighter Jet is a Reminder Cold War Tactics Are Back in the Middle East,” Chatham House, October 18, 2024, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2024/10/egypts-purchase-chinese-fighter-jet-reminder-cold-war-tactics-are-back-middle-east; Jennifer Kavanagh and Frederic Wehrey, “The Multialigned Middle East,” Foreign Affairs, July 17, 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/multialigned-middle-east-china-influence.

- 18Jon B. Alterman, “The ‘China Model’ in the Middle East,” Survival, 66 (2), https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2024.2332062.

- 19“Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2024,” U.S. Department of Defense, https://media.defense.gov/2024/Dec/18/2003615520/-1/-1/0/MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA-2024.PDF, 57, 90, 143.

- 20Michael Joseph Cohen, Fighting World War Three from the Middle East: Allied Contingency Plans, 1945–1954 (Portland, Ore.: Frank Cass, 1997), 29–32, http://discovery.lib.harvard.edu/?itemid=%7Clibrary/m/aleph%7C007421068. Joseph A. Yager and Eleanor B. Steinberg, Energy and U.S. Foreign Policy (Cambridge, Mass.: Ballinger, 1975), 326–327.

- 21Cohen, Fighting World War Three, 29–32.

- 22Rosemary A. Kelanic, Black Gold and Blackmail: Oil and Great Power Politics (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2020), 135–40.

- 23Michael Peck, “Revealed: How America and Britain Planned to Destroy the Middle East’s Oil,” National Interest, June 24, 2016, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/revealed-how-america-britain-planned-destroy-the-middle-16701.

- 24“Memorandum from the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Economic and Technology Affairs (Frost) to the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy (Komer), July 16, 1980,” in Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976, Volume XXXVII, Energy Crisis, 1974–1980, accessed November 27, 2024, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76v37/d279.

- 25“Memorandum from the Deputy Assistant Secretary…”

- 26Louise Fawcett, Iran and the Cold War: The Azerbaijan Crisis of 1946 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 83.

- 27Daniel Yergin, Shattered Peace: The Origins of the Cold War (New York: Penguin Books, 1990), 181.

- 28William L. Cleveland, A History of the Modern Middle East, 3rd ed. (Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 2004), 113–115. Fawcett, Iran and the Cold War, 83.

- 29“TREATY OF FRIENDSHIP BETWEEN PERSIA AND THE RUSSIAN SOCIALIST FEDERAL SOVIET REPUBLIC, SIGNED AT MOSCOW, FEBRUARY 26, 1921 | CIA FOIA (Foia.Cia.Gov),” accessed November 5, 2024, https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/document/cia-rdp84b00049r000701920007-1; Kristen Blake, The US-Soviet Confrontation in Iran, 1945-1962: A Case in the Annals of the Cold War (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 2009), 10.

- 30Bruce R. Kuniholm, The Origins of the Cold War in the Near East: Great Power Conflict and Diplomacy in Iran, Turkey, and Greece (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1980), 138.

- 31Kuniholm, 140.

- 32Ashley Jackson, Persian Gulf Command: A History of the Second World War in Iran and Iraq, 1st ed. (New York: Yale University Press, 2018), 355.

- 33Kuniholm, Origins, 293–294.

- 34Kuniholm, Origins, 319–325.

- 35Yergin, Shattered Peace, 181

- 36Kuniholm, Origins, 411–414.

- 37Roham Alvandi, Nixon, Kissinger, and the Shah: The United States and Iran in the Cold War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 64.

- 38“January 23, 1980: State of the Union Address,” UVA Miller Center, October 20, 2016, https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches/january-23-1980-state-union-address.

- 39Victor McFarland, Oil Powers: A History of the U.S.-Saudi Alliance (New York: Columbia University Press, 2020), 231.

- 40Yaqub, “The United States and the Persian Gulf,” 35–37.

- 41Bruce W. Jentleson, With Friends Like These: Reagan, Bush, and Saddam, 1982–1990 (New York: Norton, 1994).

- 42Eugene Gholz and Daryl G. Press, “Protecting ‘the Prize’,” Security Studies, vol. 19 (2010): 468.

- 43“Tanker War,” Strauss Center for International Security and Law, last modified August 2008, https://www.strausscenter.org/strait-of-hormuz-tanker-war/.

- 44Gholz and Press, “Protecting ‘the Prize’,” 468.

- 45Yitzhak Shichor, The Middle East in China’s Foreign Policy, 1949–1977, International Studies (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979), 6, http://discovery.lib.harvard.edu/?itemid=%7Clibrary/m/aleph%7C000852451.

- 46Sean Mirksi, “Stranglehold: The Context, Conduct, and Consequences of an American Naval Blockade of China,” Journal of Strategic Studies 36, no. 3 (2013): 385–421; Fiona S. Cunningham, “The Maritime Rung on the Escalation Ladder: Naval Blockades in a U.S.-China Conflict,” Security Studies 29, no. 4 (2020): 730–768.

- 47“Military and Security Developments…” 144

- 48Mike Sweeney, “Challenges to Chinese Blue-Water Operations,” Defense Priorities, May 1, 2024, 14–16, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/challenges-to-chinese-blue-water-operations/.

- 49Sweeney, 9–12.

- 50Dawn C. Murphy, China’s Rise in the Global South: The Middle East, Africa, and Beijing’s Alternative World Order (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2022), 32; Dalia Dassa Kaye, “America’s Role in a Post-America Middle East,” Washington Quarterly 45, no. 1 (Spring 2022): 11–12.

- 51Dale Aluf, “China’s Influence in the Middle East and Its Limitations,” Diplomat, February 16, 2024, https://thediplomat.com/2024/02/chinas-influence-in-the-middle-east-and-its-limitations/.

- 52“Oil Demand for Fuels in China Has Reached a Plateau,” IEA, March 11, 2025, https://www.iea.org/commentaries/oil-demand-for-fuels-in-china-has-reached-a-plateau.

- 53Erica Downs and Abhiram Rajendran, “China’s Slowing Oil Demand Growth is Likely to Persist and Could Impact Markets,” Center on Global Energy Policy, Columbia University, November 13, 2024, https://www.energypolicy.columbia.edu/chinas-slowing-oil-demand-growth-is-likely-to-persist-and-could-impact-markets/.

- 54Marshall I. Goldman, “Diffusion of Development: The Soviet Union,” American Economic Review 81, no. 2 (1991): 277.

- 55Marshall Goldman and Steven Baral, “Soviet Energy Problems,” Harvard International Review 3, no. 5 (February 1981): 31.

- 56Paul R. Gregory and Robert C. Stuart, Soviet Economic Structure and Performance, 4th ed. (New York: Harper & Row, 1990), 407–409.

- 57“Military Expenditure (% of GDP),” World Bank Open Data, accessed April 3, 2025, https://data.worldbank.org.

- 58Randall W. Stone, Satellites and Commissars: Strategy and Conflict in the Politics of Soviet-Bloc Trade (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996), 5.

- 59Gregory and Stuart, Soviet Economic Structure and Performance, 324–325, 342.

- 60Gregory and Stuart, Soviet Economic Structure and Performance, 332–333.

- 61Marshall I. Goldman, “The Soviet Union,” Daedalus 104, no. 4 (1975): 138; Marshall I. Goldman, “The Soviet Energy Pipeline,” Current History 81, no. 477 (October 1, 1982): 312.

- 62Marshall I. Goldman, “The Economy and the Consumer,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 38, no. 4 (April 1982): 24, https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.1982.11455721.

- 63Yanjie Huang, “Ideology Strikes Back: China’s Lessons of the Soviet Collapse, 1992–2022,” Problems of Post-Communism 71, no. 6 (November 1, 2024): 579–591, https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2023.2301108.

- 64Charles L. Glaser and Rosemary A. Kelanic, “Getting Out of the Gulf,” Foreign Affairs, December 12, 2016, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/persian-gulf/2016-12-12/getting-out-gulf, 123.

More on Middle East

By Peter Harris

February 1, 2026

Events on Middle East