Saudi Arabia is not a U.S. ally

- In 1945, President Franklin D. Roosevelt met Saudi King Abdul Aziz on the USS Quincy in Egypt, a first between U.S. and Saudi heads of state and the beginning of the bilateral relationship.

- U.S.-Saudi relations were built on shared interests, not shared values—in exchange for a reliable supply of oil, the U.S. agreed to provide security for the kingdom. However, no treaty formalized a military alliance.1Bruce Riedel, Kings and Presidents (Brookings Institution Press, March 12, 2019): 3–5; United States Treaties and Other International Agreements (United States: Department of State, 1952): 1460–1484.

- The U.S. committed to weapons sales and training for Saudi armed forces, and over time, the arrangement grew to include a substantial U.S. troop presence in Saudi Arabia. But the world has changed dramatically over the last 75 years.

- The U.S. can meet its narrow interests in the Middle East without providing unconditional support to Saudi Arabia.

- Catering excessively to the kingdom’s demands, supporting its foreign policy, and stationing U.S. troops on Saudi soil undermine U.S. interests. The U.S. should recalibrate Saudi relations to maintain a more balanced, business-like relationship.

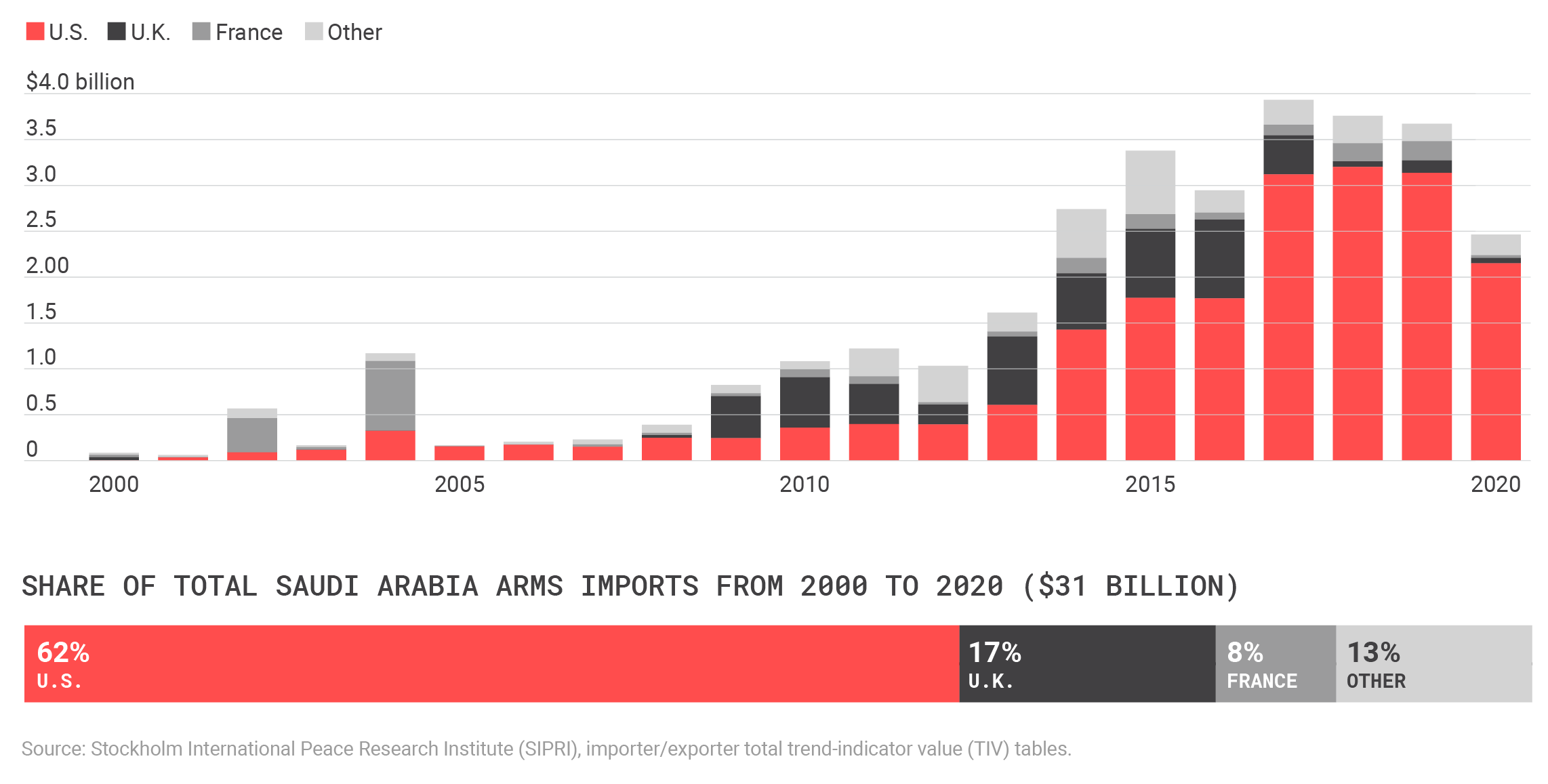

Arms suppliers to Saudi Arabia

The U.S. supplied more arms to Saudi Arabia since 2000 than all other nations combined.

Close ties to Saudi Arabia undermine U.S. interests and values

- U.S. interests in the Middle East are narrow and easily achieved: (1) defending against anti-U.S. terrorist threats and (2) preventing significant, long-term disruptions to the flow of oil. Neither requires unconditional U.S. support to Saudi Arabia.

- The U.S. can best accomplish its objectives by allowing local regional players to balance each other’s power. Saudi dominance is just as threatening to this balance as Iranian dominance, neither of which is likely to occur.

- The U.S. currently stations between 2,500 and 3,000 troops in Saudi Arabia—they serve no practical U.S. security purpose, but they provide the kingdom with an opportunity to drag the U.S. military into its conflicts.

- As 9/11 demonstrated, stationing U.S. troops in Saudi Arabia, with Mecca and Medina nearby, can create new threats by giving radical Islamic extremists a potent grievance for terrorist recruitment: 15 of 19 hijackers were from Saudi Arabia.

Oil is no reason to give Saudi Arabia a blank check

- There are two primary arguments to justify unwavering U.S. support: (1) In exchange for protection, Saudi Arabia manipulates oil prices to aid the U.S. (2) Defending Saudi Arabia avoids conquest by a would-be hegemon, which could control regional oil.

- The first theory always relied on the questionable assumption that Saudi Arabia would sacrifice its own interests for U.S. price preferences. As demonstrated in the 2020 oil price war which harmed U.S. oil firms, Saudi Arabia acts in its own interests.2Ilya Arkhipov, Will Kennedy, Olga Tanas, and Grant Smith, “How Putin Spurned the Saudis to Start a War on America’s Shale Oil Industry,” Los Angeles Times, March 9, 2020, https://www.latimes.com/business/story/2020-03-08/oil-price-war.

- The second theory fails because there is no state poised to collect much of the region’s oil supply under one flag—Iran is far too weak, and no other likely hegemons have emerged. The U.S. can manage conceivable threats from offshore.

- Markets and global reserves can quickly correct disruptions to oil exports, including Saudi Arabia’s. When output decreases and prices go up, profit motives incentivize other producers to pump more and gain market share.3Eugene Gholz and Daryl G. Press, “Protecting ‘The Prize’: Oil and the U.S. National Interest,” Security Studies, 19:3 (2010): 453–485.

- Saudi Arabia’s declining strategic importance reflects regional trends. At $3.65 trillion, the Middle East accounts for only 4 percent of global GDP.4“GDP (Current US$)—Middle East & North Africa,” World Bank, Accessed March 15, 2021, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=ZQ. The Saudi economy, the region’s largest, is the size of Pennsylvania’s.

- Despite the Saudi government’s diversification efforts, hydrocarbons comprise two-thirds of its revenue. Saudi Arabia’s oil policy is influenced by its own economic interests and budgetary needs, not by an urge to do favors for the U.S.

Unconditional U.S. support encourages Saudi Arabia’s reckless driving

- U.S. policy is sometimes premised on the notion Saudi Arabia is a bulwark of regional stability. If that assumption ever made sense, it no longer does, particularly since Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) consolidated power several years ago.

- Without fear of losing U.S. protection, Saudi foreign policy, relatively cautious for decades, has become reckless and destabilizing.

- The war in Yemen, the embargo of Qatar, the forced resignation of Lebanon’s prime minister, and an oil price war against U.S. shale companies have exacerbated the Middle East’s security problems and directly harmed U.S interests.

- U.S. support of the Saudi-led coalition’s military intervention in Yemen exacerbated a humanitarian crisis there, hindered diplomacy, and resulted in U.S. weapons falling into the hands of extremists. This entanglement undercuts U.S. interests and values.5Enea Gjoza and Benjamin H. Friedman, “End U.S. Military Support for the Saudi-Led War in Yemen,” Defense Priorities, January 2019, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/end-us-military-support-for-the-saudi-led-war-in-yemen.

Resetting the Saudi relationship will restore U.S. leverage

- With narrow interests, easily secured, the U.S. has options in the Middle East—and alternatives create leverage. Picking sides squanders U.S. power and gives undue influence to Saudi Arabia.

U.S. officials should notify their counterparts across all levels of government that it has no obligation or intention to come to Saudi Arabia’s defense. Resetting the relationship will discourage—and limit complicity in—the kingdom’s destabilizing foreign policies. - The Biden administration should remove all U.S. forces from Saudi Arabia and reduce its ground forces from the broader region, moving them offshore and then home.6Mike Sweeney, “A Plan for U.S. Withdrawal from the Middle East,” Defense Priorities, December 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/a-plan-for-us-withdrawal-from-the-middle-east.

- The U.S. transfer of air-to-ground munitions should be prohibited. These types of offensive arms sales to the kingdom buy the U.S. little influence; they encourage and enable Saudi recklessness, harming U.S. interests and values.

- The U.S. should treat Saudi Arabia like any other authoritarian power: with skepticism and at arm’s length, but always prepared to collaborate on areas of mutual interest.

Endnotes

- 1Bruce Riedel, Kings and Presidents (Brookings Institution Press, March 12, 2019): 3–5; United States Treaties and Other International Agreements (United States: Department of State, 1952): 1460–1484.

- 2Ilya Arkhipov, Will Kennedy, Olga Tanas, and Grant Smith, “How Putin Spurned the Saudis to Start a War on America’s Shale Oil Industry,” Los Angeles Times, March 9, 2020, https://www.latimes.com/business/story/2020-03-08/oil-price-war.

- 3Eugene Gholz and Daryl G. Press, “Protecting ‘The Prize’: Oil and the U.S. National Interest,” Security Studies, 19:3 (2010): 453–485.

- 4“GDP (Current US$)—Middle East & North Africa,” World Bank, Accessed March 15, 2021, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=ZQ.

- 5Enea Gjoza and Benjamin H. Friedman, “End U.S. Military Support for the Saudi-Led War in Yemen,” Defense Priorities, January 2019, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/end-us-military-support-for-the-saudi-led-war-in-yemen.

- 6Mike Sweeney, “A Plan for U.S. Withdrawal from the Middle East,” Defense Priorities, December 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/a-plan-for-us-withdrawal-from-the-middle-east.

More on Middle East

Featuring Rosemary Kelanic

October 16, 2025

Featuring Daniel Davis

October 15, 2025

Events on Middle East

virtualMiddle East, Basing and force posture, Diplomacy, Houthis, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Israel‑Hamas, Military analysis, Syria

May 16, 2025

virtualSyria, Balance of power, Basing and force posture, Counterterrorism, Middle East, Military analysis

February 21, 2025