The U.S. alliance system is based on an early Cold War balance of power that no longer exists

- Cold War military alliances were formed for sound security reasons, not U.S. benevolence: The U.S. sought to prevent the USSR from dominating Europe, which would have given it the resources to threaten the U.S.

- At the start of the Cold War, European nations were too weak to balance the USSR and required U.S. help. Today, those nations are rich, and with a far weaker—and declining—Russia, Europe faces no serious conventional threat.

- Alliances should be temporary means to an end, where burdens are distributed by capability. Today, U.S. forces generally bear the bulk of the burden, and too many U.S. leaders see that state as a permanent good.

- With a disproportionate share of the defense burden falling on U.S. taxpayers and service members, and with stronger interests in fostering capable partners rather than dependents, the U.S. should shift more security responsibilities onto its allies.

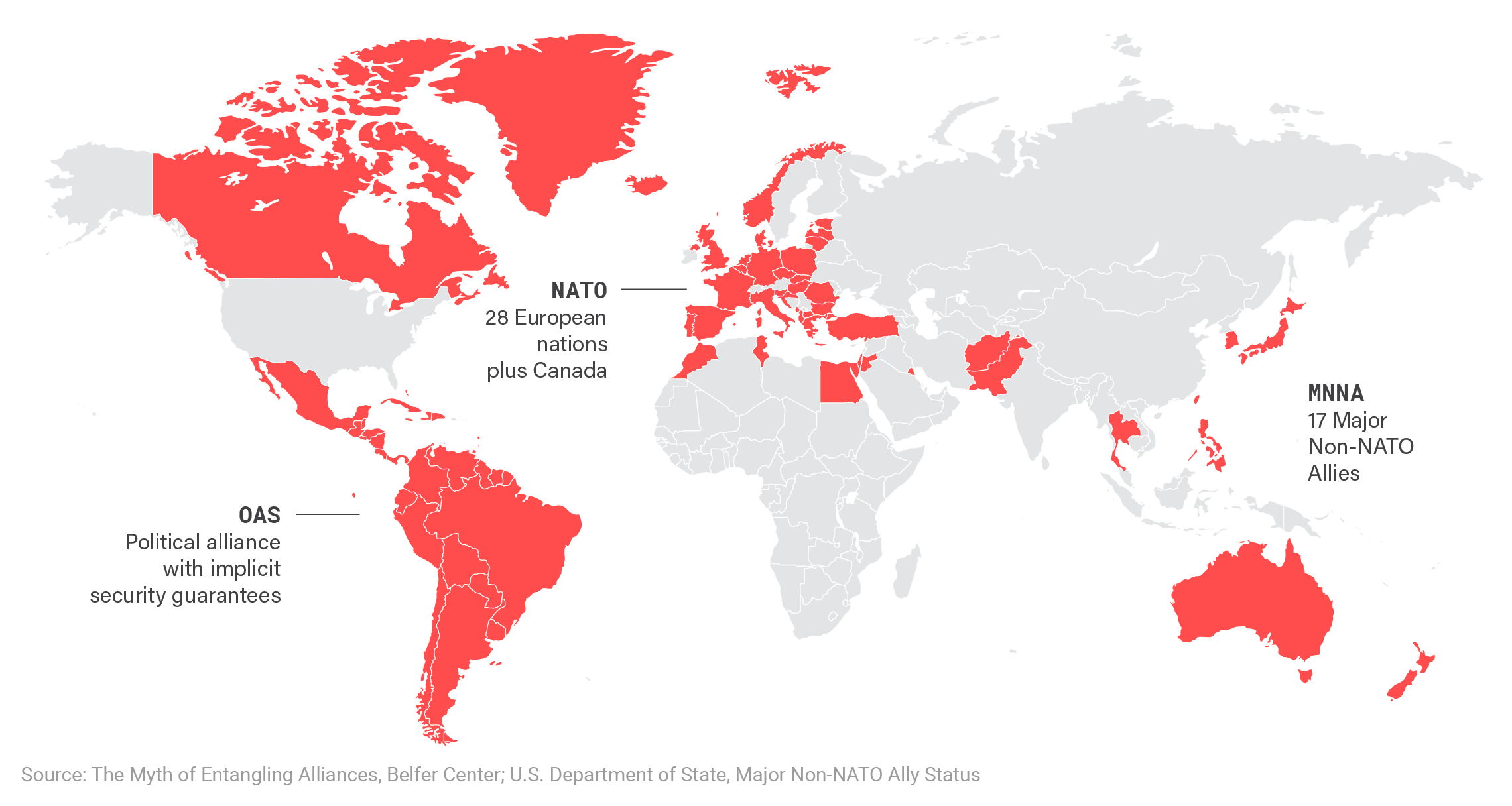

U.S. military alliances and security commitments

Various U.S. security commitments cover more than 25 percent of the world’s population in 80 countries.

Abundant U.S.-funded security encourages allied “cheap riding” and “reckless driving”

- Non-threatening security environments and the 200,000 U.S. forces overseas providing front-line defense disincentivize many allies from taking more responsibility for securing themselves.1Thomas Gibbons-Neff and Eric Schmitt, “Despite Vow to End ‘Endless Wars,’ Here’s Where About 200,000 Troops Remain,” New York Times, October 21, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/21/world/middleeast/us-troops-deployments.html.

- U.S. overprovision of security encourages allies to “cheap ride,” doing little and acting as dependents rather than partners.

- Non-U.S. NATO possesses a GDP comparable to that of the U.S., yet the U.S. provides two-thirds of the alliance’s military spending.2“Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2013-2019),” NATO, November 2019, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/pdf_2019_11/20191129_pr-2019-123-en.pdf. The U.S. in effect subsidizes Western Europe’s welfare states, as those allies forgo adequate spending on defense.3Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2013-2019),” November 2019.

- This is by design: to keep allies dependent, rather than independently capable, lest they challenge U.S hegemony. The benefits of this arrangement are not as great as defenders claim and are no longer worth the financial and strategic cost.

- The security environment also matters. Many allies, like those in Western and Central Europe, face few threats, so they spend less. South Korea and others with hostile neighbors nearby spend more, though still less than they would without U.S. protection.

- The promise of U.S. protection also incentivizes (even prospective) allies to risk conflict they would otherwise avoid—this is known as “reckless driving.” Rather than deterring conflict, some alliance arrangements can make war more likely.

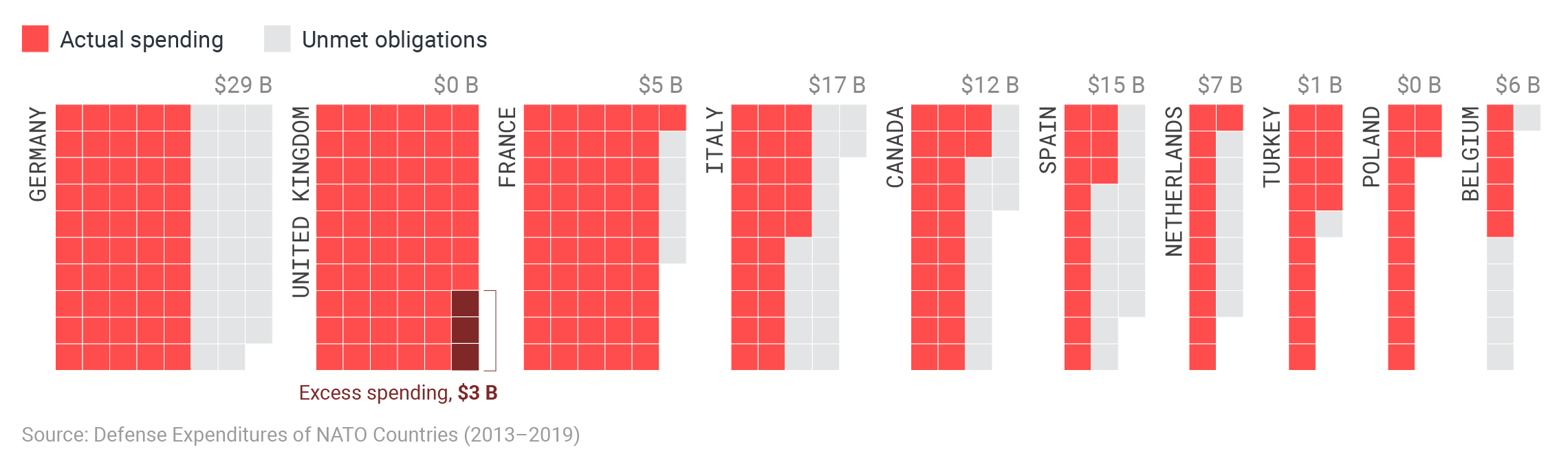

Obligated and actual military spending for the U.S. versus NATO Europe and Canada

The U.S. contributes twice as much to allied security as all other NATO nations combined. The U.S. spends 60 percent more than obligated under NATO guidelines, while other NATO states collectively spend 25 percent less than obligated.

A changing security environment demands renovating the alliance system

- U.S. leaders have long exhorted allies to spend more on security, but with the U.S. protecting them and limited threats, allies have little incentive to do so. Only by doing less for allied security can the U.S. motivate allies to build more capable militaries.

- Europe is secure, and U.S. allies are wealthy. Russia’s military is a shadow of its former self, and its economy cannot support large-scale territorial conquest. The U.S. is overinvesting in European security, while allied military capabilities degrade.

- Asia’s growing economic and political importance merits greater U.S. attention, but China currently poses little offensive threat to its neighbors (besides Taiwan), which are technologically advanced and wealthy enough to help check any potential aggression.

- Most of China’s military spending funds defensive capabilities and internal policing, not offensive platforms. China lacks a true blue water navy, and its neighborhood (nuclear rivals, mountains, and water) militates against attempts at conquest.

- The U.S. military is overstretched. With higher priorities at home, finite national resources should be husbanded responsibly. It is imperative that allies can meaningfully contribute to their own security should threats increase.

Wealthy European nations should take responsibility for the continent’s defense

- European states are not likely to invest in fielding capable, modern militaries unless the U.S. matches demands for burden sharing with a rebalancing of its military commitment.

Europe is so safe, however, that even a substantially reduced U.S. presence might not prompt greater European security investments. Even such an outcome would be better for the U.S. than the current expensive, outdated arrangement. - The U.S. should end the European Defense Initiative—which cost $6.4 billion as of 2019 and is redundant with NATO—and the corresponding deployment of U.S. troops in Eastern Europe. Europe’s major powers can do more to protect their eastern flank.

- The U.S. should scale down its other forces on the continent, including the 35,000-troop presence in Germany.

- European states should be encouraged to expand their strategic autonomy, collaborating to build joint military capabilities that will allow them to assume primarily responsibility for securing themselves.

- Europe’s GDP is 11 times that of Russia. Europe’s economic and political heft can also help the U.S. balance Russia and China’s influence in international institutions.

Asian allies can deter territorial aggression by China with U.S. weaponry

- U.S.-China relations are complex, and any potential competition between them would have economic, diplomatic, and military elements—these distinctions are important to advance U.S. interests, avoid overstretch, and profit from healthy rivalry.

- A Cold War containment approach to China carries great risk—any military conflict between the two nations could easily escalate to nuclear war through miscalculation, which is one reason, along with conventional deterrence, why war is quite unlikely.

- U.S. goals in Asia are to defend the status quo arrangement and preserve the territorial integrity of allies.

- Projecting power near China’s coast to match China’s growing capabilities would come at great risk and exorbitant cost to the U.S. economy. Asian allies must do more to balance China.

- Instead of replicating U.S. offensive military capabilities—fielding large, expensive, and vulnerable platforms—allies should adopt radar and missile networks (anti-access/area-denial systems or A2/AD) to fortify themselves (defensive defense).4Eugene Gholz, Benjamin Friedman, and Enea Gjoza, “Defensive Defense: A Better Way to Protect U.S. Allies in Asia,” Washington Quarterly, December 20, 2019, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0163660X.2019.1693103.

- A2/AD systems would make allies more resilient to conquest, while allowing the U.S. military to play a supporting, rather than primary, role in their security. This would reduce the U.S. defense burden and escalation risks, helping to avoid a great power war.

Actual versus obligated military spending for the top ten non-U.S. NATO economies

Almost all major non-U.S. NATO states failed to meet their obligations to fund their militaries at 2 percent of GDP—in many cases with a significant shortfall.

Burden shifting rather than burden sharing

- The geopolitical landscape has changed radically since U.S. military alliances were formed—these arrangements should be modernized for today’s strategic realities.

- As rapid growth in developing nations shrinks the gap between the U.S. and potential rivals, prosperous and technologically advanced U.S. allies can play a larger role in maintaining the balance of power in Europe and Asia.

- Rather than exhorting allies to do more with calls for better burden sharing, the U.S. should shift burdens onto allies by doing less—this may encourage allies to do more, but if they see their efforts as sufficient to meet local threats, that is also acceptable.

- Rather than permanently man the potential front lines, U.S. support should come from the rear if needed. By thrusting greater responsibility on allies, this posture will lessen the free-riding and reckless driving problems bedeviling U.S. alliances.

Endnotes

- 1Thomas Gibbons-Neff and Eric Schmitt, “Despite Vow to End ‘Endless Wars,’ Here’s Where About 200,000 Troops Remain,” New York Times, October 21, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/21/world/middleeast/us-troops-deployments.html.

- 2“Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2013-2019),” NATO, November 2019, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/pdf_2019_11/20191129_pr-2019-123-en.pdf.

- 3Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2013-2019),” November 2019.

- 4Eugene Gholz, Benjamin Friedman, and Enea Gjoza, “Defensive Defense: A Better Way to Protect U.S. Allies in Asia,” Washington Quarterly, December 20, 2019, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0163660X.2019.1693103.

Events on Burden sharing

virtualGrand strategy, Basing and force posture, Burden sharing, Global posture, Military analysis

October 31, 2024