July 16, 2025

War on terror tactics won’t stop Mexican drug cartels

With drug overdoses at record levels and violence in Mexico intensifying, U.S. political pressure to take on the drug cartels is mounting. In what has increasingly become a mainstream view, the Trump administration is considering employing military force, suggesting that the U.S. should treat these cartels like terrorist organizations and use tactics developed during the Global War on Terror (GWOT).

But would this approach work? Or would it risk repeating the same mistakes that defined two decades of U.S. military overreach while doing little to stymie the lucrative drug trade?

In this Q&A, Defense Priorities fellows Daniel DePetris and Christopher McCallion, the authors of a new DEFP explainer on the cartel crisis, discuss why militarized GWOT-style responses are unlikely to succeed. They offer a more effective path forward for addressing cartel violence and cross-border narcotics trafficking.

Why are U.S. officials increasingly calling for GWOT-style tactics to address Mexico’s drug cartels?

DePetris: The calls stem from growing frustration over the drug overdose crisis, especially the rise in synthetic opioids like fentanyl, and persistent cartel violence just across the U.S.-Mexico border. The Trump administration and many in Congress want a clear, decisive response and they are turning to tactics used during the Global War on Terror.

READ THE EXPLAINER

The logic is superficially appealing. Mexican cartels are transnational, well-armed, and extremely violent. Some control territory, corrupt governments, and even rival the firepower of local militaries. This has led the Trump administration to designate six major Mexican cartels as foreign terrorist organizations (FTOs), and several administration officials have suggested the possibility of authorizing military strikes or covert operations to dismantle them, much like the U.S. targeted al-Qaeda or ISIS.

But this is a fundamental error.While the cartels are nefarious actors, they do not meet the traditional definition of terrorist organizations. They don’t seek to instill political fear, promote ideology, overthrow governments, or provoke the U.S. into military conflict. Rather, they are motivated by profit. Mislabeling them invites a response that is not only legally problematic but also strategically counterproductive.

Worse, it creates the illusion that a military solution exists. That kind of framing oversimplifies a problem rooted in demand-side drug markets, institutional weakness in Mexico, and decades of ineffective prohibition strategies. The GWOT wasn’t a decisive success and led to many costs for the United States. It is certainly not a model for narcotics enforcement.

How have previous efforts to address cartel violence and narcotrafficking across the southern border fared?

McCallion: Historically, U.S. counter-cartel efforts have relied on a mix of security assistance, law enforcement cooperation, and interdiction. But over the past 15 years, those efforts have had limited success and, in many cases, made things worse.

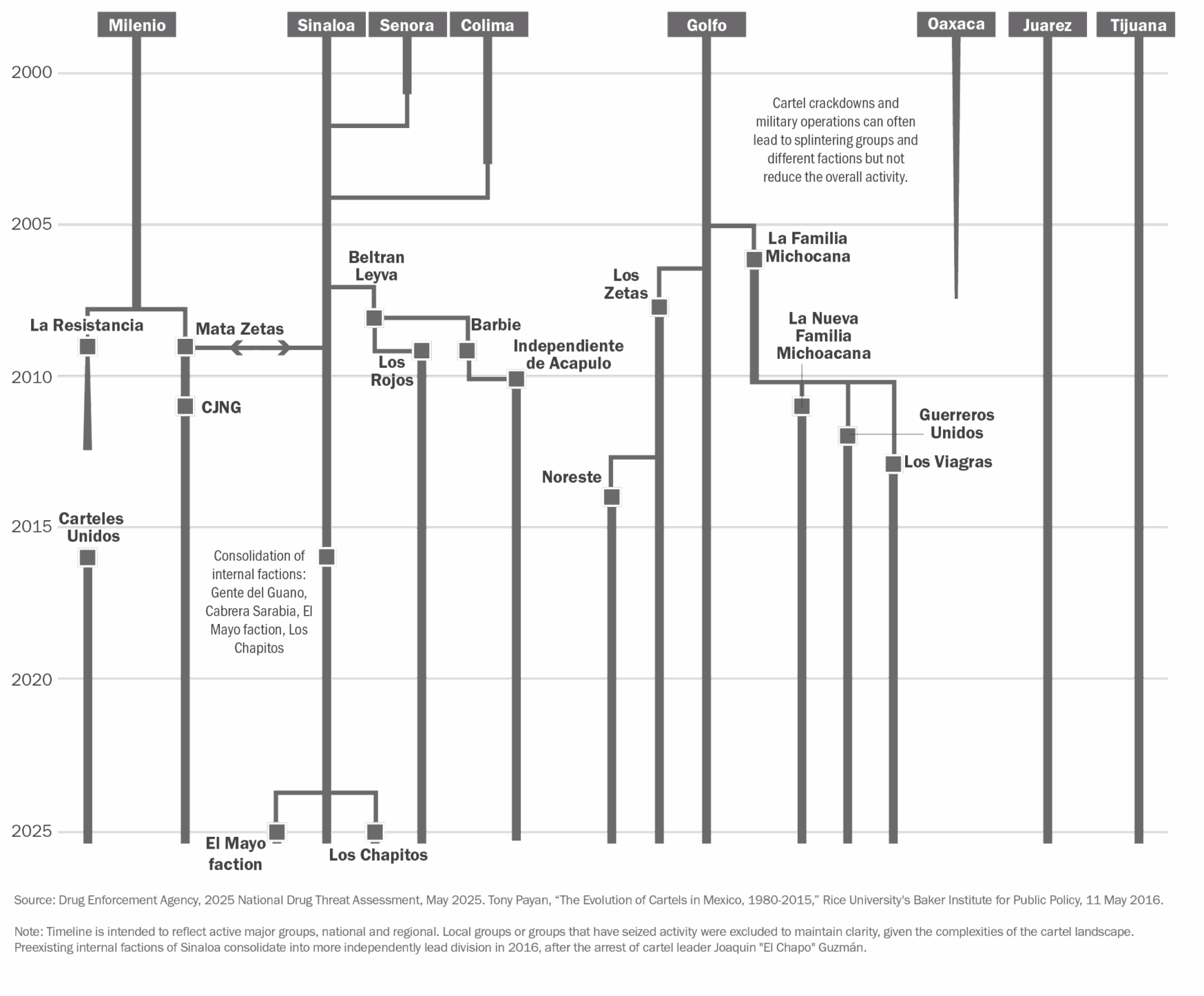

In 2008, the U.S. launched the Mérida Initiative, a $3 billion security assistance program to help Mexico’s government take a more aggressive approach to cartel crackdowns. The result was fragmentation. High-level arrests and targeted killings broke up major cartels like the Zetas and the Gulf Cartel. But rather than reducing violence, this led to more competition, more splinter groups, and more bloodshed.

Mexico’s own approach has also evolved. In recent years, the Mexican government has tried to move away from militarized crackdowns, especially under President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO). His administration adopted a ”hugs, not gunfights” strategy that emphasized social programs, poverty reduction, and avoiding direct confrontations with cartels. But, Mexico did not have the time needed for such an approach to work. So, AMLO ultimately returned to the unsuccessful militarized tactics his predecessors had used.

The Mexican military continues to play a central role in domestic security, including oversight of customs and ports. This contradictory posture—seeking to reduce violence while relying heavily on the armed forces—has produced mixed results. Violence remains high, and cartels have adapted by embedding themselves more deeply in local economies and political structures.

Meanwhile, supply-side drug enforcement hasn’t delivered. Despite decades of interdiction, narcotics remain cheap and abundant in the U.S. The shift to synthetic drugs like fentanyl, which are easier to smuggle in small quantities, has made detection even harder.

The lesson is clear: militarized or enforcement-heavy approaches have not eliminated the cartels, and have often fueled instability, corruption, and civilian harm. Throwing more force at the problem won’t fix it.

What military options could the U.S. employ, and what are the weaknesses of these approaches?

DePetris: The options being floated range from covert operations and unilateral drone strikes to direct U.S. military incursions into Mexican territory. Some proposals envision special operations forces targeting cartel leaders, or even launching airstrikes against fentanyl labs to degrade supply and undermine the revenue cartels earn from the drug trade.

But there are serious problems with all of these approaches.

First, they would violate Mexican sovereignty. Even with bilateral cooperation, any use of U.S. military force on Mexican soil would be politically explosive, both in Mexico and internationally. Unilateral action would severely damage U.S.-Mexico relations, jeopardize cooperation on issues beyond counter-narcotics, and likely provoke a nationalist backlash that empowers the very cartels we aim to weaken.

Second, these operations would be legally questionable. Cartels are criminal organizations, not enemy combatants under the laws of war. Military action against them, particularly if it’s not specifically authorized by the U.S. Congress, risks blurring legal categories and sets a dangerous precedent for similar activity in the future.

Third, they won’t solve the problem. Killing or capturing cartel leaders rarely leads to lasting disruption. In many cases, it sparks succession battles or the creation of more violent splinter groups which compete among themselves for territory and trafficking routes. And with synthetic drugs like fentanyl, production is easy to replicate. Bombing one lab won’t meaningfully change the flow.

Finally, there’s the risk of escalation. Cartels have shown they can retaliate violently, including against government officials and civilians. If the U.S. engages in military action, it could ignite a conflict that draws the U.S. deeper into Mexico’s internal struggles without any clear path to success. This escalation could also result in the cartels attacking American citizens in the homeland or abroad.

What should the U.S. do instead?

McCallion: There is no silver bullet to stop the flow of drugs into the United States and suppress cartel violence in Mexico. The key point here is that U.S. military action in Mexico would likely make the problem worse.

Here are some approaches to mitigating the violence unleashed by the cartels and the devastating flow of fentanyl into the United States:

- Strengthen law enforcement cooperation. The U.S. should improve intelligence sharing, joint investigations, and financial tracking. The U.S. has powerful tools to disrupt illicit finance, target supply chains, and prosecute traffickers using the criminal justice system. We should use them.

- Reduce the flow of guns from the U.S. to Mexico and drug demand at home. The U.S. government could also reduce cartel-related violence if it effectively controlled border traffic, including disrupting the flow of guns from the United States into Mexico by better enforcing anti-trafficking laws. The U.S. opioid crisis is a major driver of cartel profits. Lawmakers should consider drug reform measures to reduce the demand for drugs in the United States, as well as funding for mental health and addiction treatments.

- Enhance border technology and detection. Most fentanyl enters through legal ports of entry, not remote crossings. Investment in scanners, personnel, and data analytics will do more to interdict drugs than walls or troop deployments.

- Support governance reform in Mexico. This should include anticorruption efforts, judicial reform, and capacity-building for Mexican institutions. Progress will be slow and uneven, but it’s the only path to durable change.

- Avoid relying on militarized thinking and rhetoric. It inflames tensions, distorts legal frameworks, and creates unrealistic public expectations about what U.S. power can achieve.

Ultimately, cartel violence is a chronic challenge, not a war to be won. It requires persistent effort, not shock-and-awe campaigns. The U.S. must resist the urge to militarize a problem that demands governance, cooperation, and law enforcement.

The U.S. can’t bomb its way out of a drug crisis. Mexican cartels are a serious challenge, but they are not terrorists and the Global War on Terror is the wrong model. The U.S. needs a smarter, more restrained strategy rooted in law, diplomacy, and public health—not escalation and overreach.

More on Western Hemisphere

November 3, 2025

By Alexander Downes and Lindsey O'Rourke

October 31, 2025

Featuring Benjamin Friedman

October 30, 2025

Featuring Daniel DePetris

October 28, 2025

Featuring Jennifer Kavanagh

October 27, 2025

Featuring Jennifer Kavanagh and Daniel DePetris

October 23, 2025