Key points

- Recent developments in international affairs and military technology have led some analysts to conclude that the nuclear revolution, which purportedly prevents war between nuclear powers, no longer has much effect—that the world is getting safer for nuclear war or conventional war beneath the nuclear umbrella.

- This conclusion is wrong; technological change has not meaningfully shifted the political calculus pacifying relations between nuclear weapons states.

- The war in Ukraine demonstrates the continued strength of nuclear restraint: while Russian President Vladimir Putin is risk-acceptant and brutal, he did not attack a country protected by U.S.-extended deterrence, and, like NATO members, he appears deterred by the possibility that a Russia-NATO war could escalate out of control.

- North Korea provides another example of the endurance of mutual deterrence: Despite heated rhetoric and a barrage of missile tests, North Korea remains deterrable, and its small arsenal has also been able to deter the United States.

- Because the chances of nuclear war are usually low but never zero, the nuclear age should continue to be an era of great power restraint. Traditional foreign policy approaches emphasizing strategic ambiguity and arms control, including with China, remain useful tools to help keep the peace.

Nuclear deterrence today

From the beginning of the nuclear era 78 years ago, observers had an inkling that nuclear weapons had fundamentally changed international politics.1Bernard Brodie, ed., The Absolute Weapon: Atomic Power and World Order (New York: Harcourt, Brace, and Company, 1946). When a single bomb could destroy a city in the blink of an eye, war between great powers, always terrifying, became too awful to contemplate. This feeling strengthened considerably when the two Cold War superpowers developed second-strike forces, in which the “loser” in a nuclear war could hit the “winner” back with damage that any country would find unacceptable. The implications were so sweeping that they earned the name “nuclear revolution”: the idea that all sides would regret having fought a nuclear war, and major wars now could not be “won” by any reasonable definition of the term.2Robert Jervis, The Meaning of the Nuclear Revolution: Statecraft and the Prospect of Armageddon, Cornell Studies in Security Affairs (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1990).

Ever since, the world has lived with “great security and enormous insecurity”3Robert Jervis, “The Nuclear Revolution and the Common Defense,” Political Science Quarterly 101, no. 5 (1986): 690.: Nuclear war is always possible and would be terrible, but precisely because of the anticipated terror, it is also highly unlikely. Moreover, nuclear use has come to be seen as off-limits, and breaking the taboo would have ramifications beyond the destructive power of the weapons themselves.4Nina Tannenwald, The Nuclear Taboo: The United States and the Non-Use of Nuclear Weapons Since 1945 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007); Thomas C. Schelling, “An Astonishing 60 Years: The Legacy of Hiroshima,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103, no. 16 (2006): 6089–93. The general effect has been an uneasy but persistent peace between nuclear-capable powers.

For some observers, today’s nuclear politics calls these fundamentals into question. They think we’ve entered a new and more dangerous nuclear age where the stability of the nuclear revolution is gone, and extended deterrence, in which a great power deters attacks against non-nuclear allies, is increasingly precarious. The biggest reason for this new thinking is that technology has jeopardized second-strike stability. With new weapons that can precisely target opponents’ forces, “the task of securing nuclear arsenals against attack is far more difficult than it was in the past.”5See the abstract for Keir A. Lieber and Daryl G. Press, “The New Era of Counterforce: Technological Change and the Future of Nuclear Deterrence,” International Security 41, no. 4 (April 2017): 9–49. Furthermore, smaller nuclear states have incentives to “go early and go massively” in a conflict or crisis to avoid losing their ability to defend themselves in a preemptive attack.6Vipin Narang, “Why Kim Jong Un Wouldn’t Be Irrational to Use a Nuclear Bomb First,” Washington Post, September 8, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/why-kim-jong-un-wouldnt-be-irrational-to-use-a-nuclear-bomb-first/2017/09/08/a9d36ca4-934f-11e7-aace-04b862b2b3f3_story.html. Finally, nuclear powers like Russia and North Korea appear willing to run great risks to achieve their objectives. Focusing only on these shifts can make the new nuclear age look unstable and frightening.

Yet, while concern is warranted, panic is unnecessary. The continuities between the earlier nuclear age and the present one are at least as important as the changes. War between great powers is still unlikely because countries continue to be afraid of cornering nuclear adversaries or attacking their homelands. Extended deterrence is also holding up impressively well. Despite loud threats, even leaders of so-called rogue states do not reach for nuclear weapons like they are just another tool in the chest. The forces that have kept nuclear weapons from exploding in anger—mutual vulnerability, fear of uncontrolled escalation, and a tradition of nonuse—are still with us.

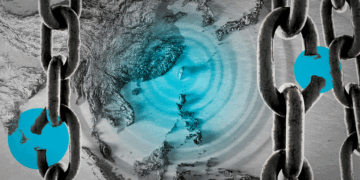

Estimated global nuclear warhead inventories

As the cases below detail, these forces are likely to prevent nuclear war even as the nuclear revolution faces tough tests. Despite the recklessness of the initial invasion of Ukraine, Russia is only engaging in behaviors it believes do not invite existential threats to itself. Likewise, North Korea’s nuclear and missile testing may be provocative, but the regime is not suicidal and can thus be deterred.

As a result, the best approaches to U.S. nuclear security are familiar: arms control when possible, threats that leave something to chance when necessary, and other tried-and-true recipes for nuclear nonuse and deterrence. The explainer concludes with thoughts about how these lessons apply to U.S.-Chinese relations, which may face difficult tests of their own in the coming years.

Continuity in the new nuclear age

Today’s nuclear revolution skeptics point to at least three reasons why the new nuclear age is increasingly dangerous. First, they argue that nuclear forces, which may have been more vulnerable than commonly thought during the Cold War,7Austin Long and Brendan Rittenhouse Green, “Stalking the Secure Second Strike: Intelligence, Counterforce, and Nuclear Strategy,” Journal of Strategic Studies 38, no. 1–2 (2015): 38–73. are even less secure today due to the increased accuracy of weapons and surveillance capabilities.8Lieber and Press, “The New Era of Counterforce”; Keir A. Lieber and Daryl G. Press, The Myth of the Nuclear Revolution: Power Politics in the Atomic Age (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2020); Andrew Futter, “Deterrence, Disruptive Technology and Disarmament in the Third Nuclear Age,” Hiroshima Organisation for Global Peace, April 2022, https://hiroshimaforpeace.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Deterrence-Disruptive-Technology-and-Disarmament-in-the-Third-Nuclear-Age.pdf. The nuclear revolution, the argument goes, is rooted in the notion that “losers” can hit “winners” back in a nuclear war. If some nuclear-armed states conclude that their technology and intelligence gathering allow them to knock out the other side’s forces in a disarming first strike, they may be tempted to act on this advantage in a crisis or low-level war. If true, a key stabilizing force of the nuclear era is waning.

Second, relatively recent additions to the nuclear club, such as North Korea (and soon, possibly Iran), will likely have a more difficult time deterring much larger adversaries like the United States. With smaller and more vulnerable arsenals falling under the constant watch of spy satellites, small nuclear club members could face strong “use them or lose them” pressures.9Narang, “Why Kim Jong Un Wouldn’t Be Irrational to Use a Nuclear Bomb First.” Third, nuclear arsenals may provide a shield, emboldening today’s ambitious and expansionary leaders to be more aggressive at lower levels of escalation.10Caitlin Talmadge, “What Putin’s Nuclear Threats Mean for the U.S.,” Wall Street Journal, March 3, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/what-putins-nuclear-threats-mean-for-the-u-s-11646329125. In sum, the skeptics warn, “Our theories and understanding derived from the Cold War bipolar nuclear competition leave us ill-equipped to handle the daunting challenges of this new nuclear age.”11Vipin Narang and Scott D. Sagan, eds., The Fragile Balance of Terror: Deterrence in the New Nuclear Age (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2023), 2.

The new age has already put the nuclear revolution to early tests in Eastern Europe and on the Korean Peninsula. But, contrary to what the skeptics’ theories might lead us to believe, the United States is not pressing its advantage against North Korea, confident that a counterforce strike could limit or eliminate retaliatory damage. Nor is Russia pursuing limitless conventional aggression without fear of escalation.

Why not? Because while skeptics of the nuclear revolution may be right about some of the technical developments and new challenges,12For a recent piece contending on more technical grounds that survivability is still running ahead of developments in counterforce, see Christopher Clary, “Survivability in the New Era of Counterforce,” The Fragile Balance of Terror: Deterrence in the New Nuclear Age, ed. Vipin Narang and Scott D. Sagan (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2023), 154–81. they are less persuasive about the political implications. As these cases show, most political leaders do not seem to believe in nuclear war victories. Instead, they threaten mutual defeat or hard-to-control escalation to deter adversaries. Nuclear states still compete, but the competition is circumscribed. When nuclear adversaries get too close to war, they work hard, often (implicitly) together, to avoid catastrophe.13To see how the Cuban Missile Crisis fits this characterization, see Serhii Plokhy, Nuclear Folly: A History of the Cuban Missile Crisis (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2021).

One payoff is that nuclear deterrence is not nearly as difficult as some claim, even in the new era.14For a Cold War-era argument that nuclear deterrence is “not so difficult,” see Robert Jervis, The Illogic of American Nuclear Strategy (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1984). To convince readers that the United States needs to invest in various new technologies, some foreign policy elites have suggested that it “must” convince adversaries that it has both the capabilities to “thwart any aggressive act” and the resolve to follow through on its threats.15Michèle A. Flournoy, “How to Prevent a War in Asia,” Foreign Affairs, June 18, 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-06-18/how-prevent-war-asia. See also Eric Schmidt and Robert O. Work, “How to Stop the Next World War,” Atlantic, December 5, 2022, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/12/us-china-military-rivalry-great-power-war/672345/. Yet Cold War history and the cases below show that it is often sufficient for an adversary to believe that escalation might get out of control to be deterred. Because all sides fear such an outcome, and new military investments or demonstrations of resolve can provoke the very acts they intend to deter, the United States should continue looking for opportunities to begin or restart arms control talks, even with adversaries.

Russia, Ukraine, NATO, and nuclear deterrence

Many analysts see the war in Ukraine as a sign that core aspects of the nuclear revolution, like nuclear deterrence and extended deterrence,16Mark B. Schneider, “Countering Putin’s Nuclear Threats,” RealClearDefense, July 6, 2022, https://www.realcleardefense.com/articles/2022/07/06/countering_putins_nuclear_threats_840988.html; Nadia Schadlow, “Why Deterrence Failed Against Russia,” Wall Street Journal, March 20, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/why-u-s-deterrence-failed-ukraine-putin-military-defense-11647794454; Mike Gallagher, “Biden’s ‘Integrated Deterrence’ Fails in Ukraine,” Wall Street Journal, March 29, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/biden-integrated-deterrence-fails-ukraine-russia-invasion-taiwan-xi-china-diplomacy-sanctions-hard-power-defense-spending-budget-negotiations-11648569487; Liam Collins and Frank Sobchak, “U.S. Deterrence Failed in Ukraine,” Foreign Policy, February 20, 2023, https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/02/20/ukraine-deterrence-failed-putin-invasion/. are failing. In fact, the case serves just about the opposite conclusion, showing how the prospect of mass destruction limits both sides’ options and prevents escalation.

The possibility of nuclear use has haunted the Russian invasion of Ukraine since the renewal of hostilities in early 2022. Russia has the world’s largest nuclear arsenal.17“Nuclear Weapons: Who Has What at a Glance,” Arms Control Association, January 2022, https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/Nuclearweaponswhohaswhat. Russian President Vladimir Putin and other Russian officials have issued a series of nuclear threats, only some of which can be described as veiled. While few experts have called the use of nuclear weapons likely, many have expressed concern that the chances are higher than they have been since the Cold War.18Giulia Carbonaro, “Risk of Nuclear Conflict at Highest Point Since Height of Cold War—SIPRI,” Newsweek, June 13, 2022, https://www.newsweek.com/risk-nuclear-conflict-highest-point-since-height-cold-war-sipri-1715161; Alvin Powell, “60 Years After Cuban Missile Crisis, Nuclear Threat Feels Chillingly Immediate,” Harvard Gazette, October 17, 2022, https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2022/10/sixty-years-after-cuban-missile-crisis-nuclear-threat-feels-chillingly-immediate/; Daniel de Visé, “Americans’ Nuclear Fears Surge to Highest Levels since Cold War,” Hill, October 14, 2022, https://thehill.com/policy/defense/3687396-americans-nuclear-fears-surge-to-highest-levels-since-cold-war/. Can the nuclear revolution and all that it entails—deterrence and nonuse—endure this challenge?

At the risk of stating the obvious, Russia’s initial invasion of Ukraine is not a failure of nuclear deterrence by the United States and its allies. Ukraine did not have a formal military alliance with a nuclear power ahead of the war. It does not have nuclear weapons itself. In this narrow sense, the war has not tested the nuclear revolution. However, there is still a possibility that the situation could escalate to a war between NATO and Russia. How is the nuclear revolution holding up? Are both sides acting as if they have escaped a state of mutual vulnerability and the caution that this condition entails?

The signs are actually encouraging thus far.19Collin Meisel, “Failures in the ‘Deterrence Failure’ Dialogue,” War on the Rocks, May 8, 2023, https://warontherocks.com/2023/05/failures-in-the-deterrence-failure-dialogue/. Russia and its nuclear adversaries eye each other warily and issue threats, but both sides have avoided crossing each other’s red lines, and the chances of direct conflict are low. Some observers have expressed concern that because nuclear war at the highest levels of intensity is unthinkable, President Putin would conclude that fighting against NATO countries at lower escalation levels would be permissible.20Emma Ashford and Joshua Shifrinson, “How the War in Ukraine Could Get Much Worse,” Foreign Affairs, March 8, 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/ukraine/2022-03-08/how-war-ukraine-could-get-much-worse. But there is no evidence that President Putin believes a limited NATO-Russia war is safe. In fact, he has suggested the opposite, claiming that if Ukraine joined NATO, then NATO countries would “automatically” be at war with Russia, and such a war could not be limited. In early February 2022, he told a French journalist, “Russia is a military superpower and a nuclear superpower . . . There will be no winners and you will be drawn into this conflict against your own will.”21David Herszenhorn and Giorgio Leali, “Defiant Putin Mauls Macron in Moscow,” Politico, February 7, 2022, https://www.politico.eu/article/vladimir-putin-russia-welcomes-emmanuel-macron-france-into-his-lair-kremlin-ukraine/.

Russia has been careful not to target any NATO country openly and directly, whether that country has its own nuclear arsenal or not. Extended deterrence is supposed to be more challenging than this. Doubts that the United States would retaliate against a Soviet strike on Western Europe, thereby opening itself up to attack, inspired the French to secure independent nuclear capabilities in the late 1950s and early 1960s. French leader Charles de Gaulle was worried that the United States would not “trade New York for Paris.”22Reid Pauly, “The Tangled Fates of Pittsburgh and Paris,” War on the Rocks, June 12, 2017, https://warontherocks.com/2017/06/the-tangled-fates-of-pittsburgh-and-paris/. It is not unreasonable to assume Eastern European countries today share similar concerns. Would the nuclear-armed NATO countries be willing to escalate against Russia for the sake of Poland or Lithuania? Apparently, Russia thinks that the risk is too high: it has been wary of attacking NATO supply lines to Ukraine at their sources, despite the support being instrumental in slowing and sometimes rolling back the Russian invasion.23Vivienne Machi, “Inside the Multinational Logistics Cell Coordinating Military Aid for Ukraine,” Defense News, July 21, 2022, https://www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2022/07/21/inside-the-multinational-logistics-cell-coordinating-military-aid-for-ukraine/.

At the same time, deterrence has limited NATO’s ability to push back against Russia directly. While being deterred can be frustrating, the alternative—a great power war with no clear ceiling of escalation—would be worse.

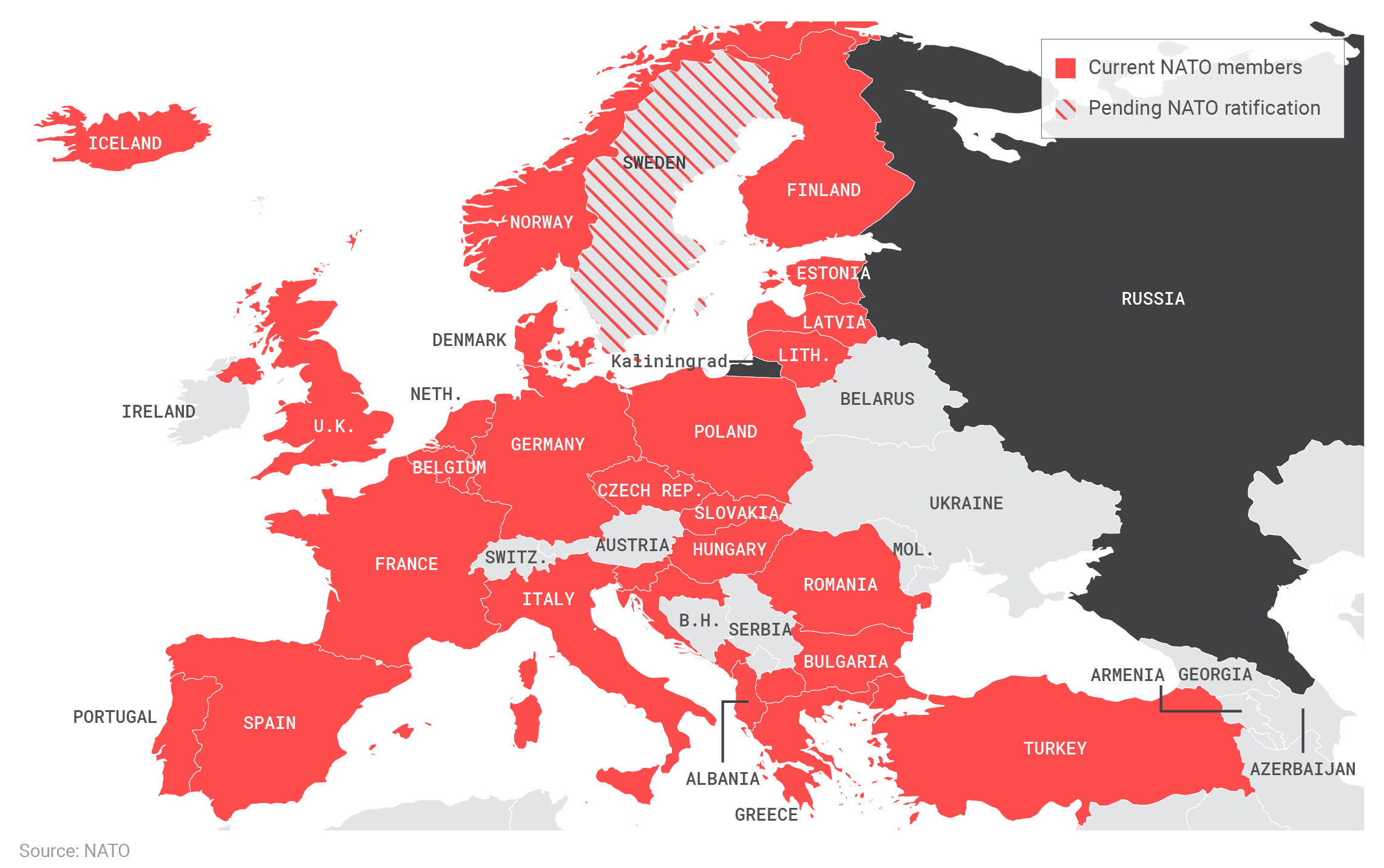

NATO vs. Russia

Despite its nuclear saber-rattling, Russia has not attacked any NATO members. The alliance maintains a formidable nuclear deterrent. However, since Ukraine is not a NATO member, there was little the alliance could do to deter Russia from launching its invasion last year.

NATO’s most challenging deterrence task has involved convincing Russia that using one or more of its approximately 2,000 tactical nuclear weapons in Ukraine would be too costly. Tactical nuclear weapons are primarily designed for battlefield use and have a limited range and yield but are still much more powerful than conventional arms.24Helene Cooper, Julian E. Barnes, and Eric Schmitt, “Russian Military Leaders Discussed Use of Nuclear Weapons, U.S. Officials Say,” New York Times, November 2, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/02/us/politics/russia-ukraine-nuclear-weapons.html. The United States and its allies have strong reasons for deterring Russian use of all nuclear weapons. While the nuclear taboo might not evaporate due to a single violation, we cannot predict the potential effects.25On how the chemical weapons taboo has weathered violations, see: Richard Price, “How Chemical Weapons Became Taboo,” Foreign Affairs, January 22, 2013, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/syria/2013-01-22/how-chemical-weapons-became-taboo. The world is better off not learning.

The challenge would be familiar to students of the nuclear revolution: Trying to deter with threats that are difficult to make credible, without provoking the deterrence target to establish credibility. The problem calls for a “threat that leaves something to chance.”26Thomas C. Schelling, The Strategy of Conflict (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1960). Any NATO guarantee to meet nuclear use with nuclear use would lack credibility because Russia has more at stake in Ukraine and NATO would be opening itself up to devastating retaliation which Russia, despite its conventional fighting limitations, could deliver. But NATO could credibly threaten to put in motion an escalatory process that neither side could fully control in response to Russian nuclear use. Russia might decide that the risks of such a development are too high.

Not only does the ambiguity of a threat that leaves something to chance help the threatener overcome questions of credibility, but it also allows for strategic flexibility. As international relations scholar Richard Betts explains, past American leaders “made their threats vague enough that they avoided being boxed into a stark choice between going ahead with escalation or being exposed as bluffers.”27Richard K. Betts, Nuclear Blackmail and Nuclear Balance (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 1987), 13.

In general, the Biden administration has used ambiguous threats wisely. While saying that the United States would work to prevent “World War III,” one administration official also said that “all bets are off” if Russia starts using nuclear weapons.28David E. Sanger et al., “U.S. Makes Contingency Plans in Case Russia Uses Its Most Powerful Weapons,” New York Times, March 23, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/23/us/politics/biden-russia-nuclear-weapons.html. President Joe Biden himself said that Russian nuclear use might be the first step to “Armageddon.”29Sam Fossum, Kaitlan Collins, and Paul LeBlanc, “Biden Offers Stark ‘Armageddon’ Warning on the Dangers of Putin’s Nuclear Threats,” CNN, October 7, 2022, https://www.cnn.com/2022/10/06/politics/armageddon-biden-putin-russia-nuclear-threats/index.html. The potential for out-of-control escalation may be enough to deter Russia while keeping the United States’ strategic options open.

To pursue a flexible policy, U.S. opinion leaders should encourage a robust domestic debate over the best approach to the war in Ukraine. One might expect the United States to benefit more from “speaking with one voice” on foreign policy. But open debate is a strength, not a weakness. It allows the Biden administration to play a strategy of both cooperation and retaliation understood by game theorists to lead to superior outcomes in international crises.30Robert Axelrod, The Evolution of Cooperation (New York: Basic Books, 1984). If President Putin wants to escalate against NATO, he must be concerned that he could put U.S. hawks in the driver’s seat. If he wants to take a more conciliatory, diplomatic route, he can anticipate that the United States will have a faction ready to pressure Biden to respond in kind.

Open debate, then, is not just in line with liberal-democratic principles; it is also a strategic advantage. As such, gatekeepers of the United States’ foreign policy debate should welcome a plethora of views to the table. Well-reasoned political ideas should be challenged vigorously, but they should not be shut out.

If, tragically, U.S. threats fail to dissuade Russia from using nuclear weapons within Ukraine’s borders, it is important to recall the extreme degree of difficulty in American deterrence policy. Russia is fighting a neighboring country without a formal alliance with the United States or any other nuclear power. President Putin’s regime has shown a willingness to bear substantial costs in pursuit of its objectives in Ukraine. At times, Russia has found itself backpedaling in the war. Would it be willing to concede ground while leaving its substantial stockpile of tactical nuclear weapons on the shelf, perhaps in part because of threats of escalation from the United States and its allies that may or may not be credible? The answer might be yes.31Deterrence is not the only conceivable reason for Russian nuclear restraint. For example, William Alberque argues that lack of suitable targets for Russian nuclear use and potential alienation of India and China (an indicator that the nuclear use taboo may still be having an effect) are also key factors. Still, Alberque also repeatedly mentions the “threat of intervention and escalation” by NATO as another plausible reason for Russian nuclear nonuse. See William Alberque, “Russia Is Unlikely to Use Nuclear Weapons in Ukraine,” International Institute for Strategic Studies, October 10, 2022, https://www.iiss.org/blogs/analysis/2022/10/russia-is-unlikely-to-use-nuclear-weapons-in-ukraine. But if deterrence does fail, it does not mean the United States grievously erred. We should not conclude that deterrence is dead if it fails in this very hard case.

Rhetoric and reality on the Korean Peninsula

U.S.-North Korean relations are another example of mutual deterrence continuing to hold despite official concern. In some ways, the Korean Peninsula has been heating up again as a potential flashpoint for nuclear conflict. The regime in Pyongyang continues to conduct frequent missile tests, with some flying over Japan or landing near South Korean territorial waters.32Choe Sang-Hun, “North Korea Launches 23 Missiles, Triggering Air-Raid Alarm in South,” New York Times, November 2, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/01/world/asia/north-korea-missile-launch.html; Motoko Rich and Choe Sang-Hun, “North Korea Fires Powerful Missile, Using Old Playbook in a New World,” New York Times, October 3, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/03/world/asia/japan-north-korea-missile.html. Meanwhile, South Korea and the United States have again held large-scale, live-fire military exercises.33Doina Chiacu and David Brunnstrom, “North Korea Demands the U.S., South Korea Halt Joint Military Drills,” Reuters, October 31, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/north-korea-calls-united-states-south-korea-stop-joint-military-exercises-2022-10-31/; Josh Smith, “U.S. Helicopters Hold First Live-Fire Drills in South Korea since 2019,” Reuters, July 25, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/us-helicopters-hold-first-live-fire-drills-skorea-since-2019-2022-07-25/. North Korea loathes the exercises because they rehearse a preemptive strike against the DPRK and because military exercises are sometimes a cover for real invasions.34Jordan Bernhardt and Lauren Sukin, “Joint Military Exercises and Crisis Dynamics on the Korean Peninsula,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 65, no. 5 (November 2020): 863.

North Korea and South Korea at night

Due to these developments, some observers fear we could be heading toward the dan gerous days of six years ago.35Jessie Yeung, Paula Hancocks, and Yoonjung Seo, “Why Is North Korea Firing so Many Missiles—and Should the West Be Worried?,” CNN, October 8, 2022, https://www.cnn.com/2022/10/07/asia/north-korea-missile-testing-frequency-explainer-intl-hnk/index.html. In 2017, the Korean Peninsula saw not only U.S.-South Korea joint exercises and North Korean testing, but also very heated rhetoric. President Donald Trump and Chairman Kim Jong-un led the chest-thumping: President Trump threatened to “totally destroy” North Korea with “fire and fury,” and Chairman Kim talked of “taming” the adversary with “fire.” The warnings were followed by dutiful subordinates doing their level best to create a vision of victory in war.

However, a closer look at the supposed “winning” scenarios makes it unsurprising that neither side ultimately favored war. Collision with reality began early. According to TIME, in April 2017, briefers showed President Trump a well-known satellite image of the Korean Peninsula at night. President Trump asked why Seoul was so close to the North Korean border and declared that its residents would “have to move,”36Peter Bergen, “The Generals Tried to Keep Trump in Check. What Happens to Foreign Policy Now That They’ve Left?,” TIME, December 5, 2019, https://time.com/5744414/trump-generals-military-experience/. presumably to blunt a North Korean response to a U.S.-South Korean joint attack. To put it mildly, a strategy contingent on South Korea abandoning its capital and largest city was unlikely to win much support.

Those responsible for providing President Trump with military options against North Korea did not paint a pretty picture. Secretary of Defense James Mattis told a House committee that “[i]t would be a war like nothing we have seen since 1953,” when the last Korean War killed more than 2.5 million people.37Hearing on National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018 and Oversight of Previously Authorized Programs, United States House of Representatives, 115 Cong. 1 (2017), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-115hhrg26739/html/CHRG-115hhrg26739.htm.

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Joseph Dunford worked hard to keep threats against North Korea credible, but in describing the war, he recalled an even more deadly precedent. At an Aspen Institute forum, he said that a war on the peninsula “would be horrific, and it would be a loss of life unlike any we have experienced in our lifetimes, and I mean anyone who’s been alive since World War II has never seen the loss of life that could occur if there’s a conflict on the Korean Peninsula.”38Nahal Toosi, “Dunford: Military Option for North Korea Not ‘Unimaginable,’” Politico, July 22, 2017, https://www.politico.com/story/2017/07/22/dunford-north-korea-military-option-not-unimaginable-240851.

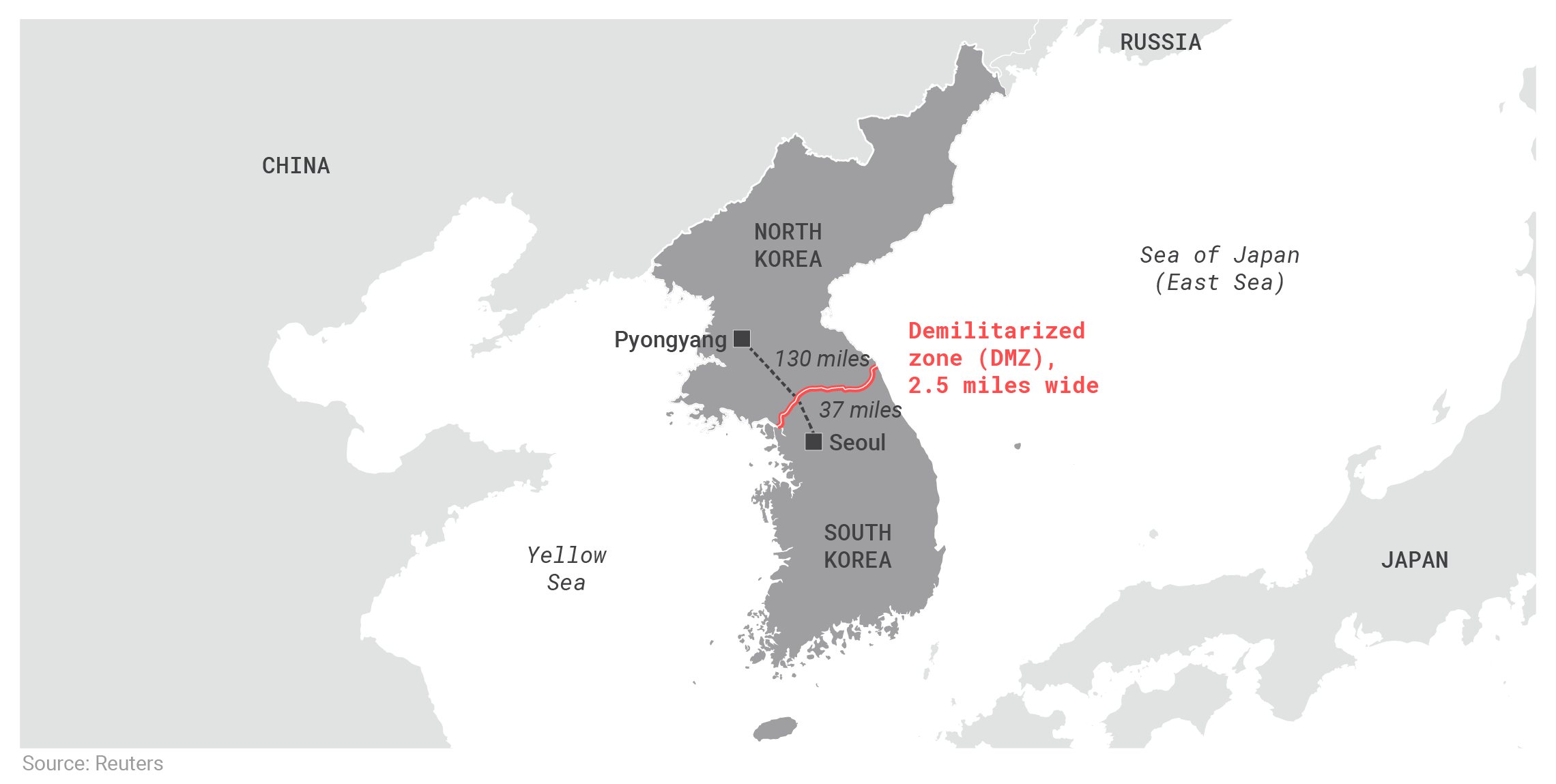

Map of the Korean Peninsula

Seoul, the capital of South Korea, is approximately 40 miles from the DMZ and 170 miles from Pyongyang, the capital of North Korea.

The Trump administration may have also considered limited strikes against North Korea—what the press called the “bloody nose” option—but circumstantial evidence suggests that the U.S. Department of Defense saw the move as prohibitively risky. On a 2021 public panel, Gen. Vincent Brooks, the top U.S. commander in South Korea in 2017, recommended against U.S. or South Korean strikes to thwart imminent North Korean missile tests since no one could be confident that Pyongyang would see the attacks as limited rather than a casus belli.39“2nd Harvard Korean Security Summit: ‘Korea—An Oracle of Global Trends,’” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, February 10, 2021, https://www.belfercenter.org/event/2nd-harvard-korean-security-summit-korea-oracle-global-trends.

Less is known about North Korea’s theory of victory, but what has been revealed is telling. The North Koreans have focused most of their rhetorical arrows on what they would do to the United States if forced. For instance, a Foreign Ministry spokesman warned that North Korea would “strike a merciless blow at the heart of the U.S. with our powerful nuclear hammer” if the United States should “dare to show even the slightest sign of attempt to remove our supreme leadership.”40Sofio Lotto Persio, “North Korea Threatens to Strike U.S. With ‘Powerful Nuclear Hammer,’” Newsweek, July 25, 2017, https://www.newsweek.com/north-korea-threatens-strike-us-heart-powerful-nuclear-hammer-honed-and-641482. North Korea has said much less about the consequences of an American response, but what it has said—admitting that enormous casualties were likely and only “a few thousand” would still survive—bolsters the idea that North Korea would prefer almost any other outcome to nuclear war.41Evan Osnos, “The Risk of Nuclear War with North Korea,” New Yorker, September 7, 2017, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/09/18/the-risk-of-nuclear-war-with-north-korea.

In more candid moments, U.S. officials have admitted that North Korea has enough nonnuclear firepower to ensure war is not worth the price. Near the end of his time as President Trump’s chief political strategist, Steve Bannon told a journalist, “There’s no military solution [to North Korea’s nuclear threats], forget it. Until somebody solves the part of the equation that shows me that ten million people in Seoul don’t die in the first 30 minutes from conventional weapons, I don’t know what you’re talking about, there’s no military solution here, they got us.”42Robert Kuttner, “Steve Bannon, Unrepentant,” American Prospect, August 16, 2017, https://prospect.org/api/content/d18c3f64-4596-5ac2-b9e2-3d47df0be592/. Emphasis added. The North Korean nuclear arsenal only reinforces the central point: Whether U.S. officials like it or not, North Korea can deliver damage that the United States would find unacceptable compared to any potential gain that war might yield.

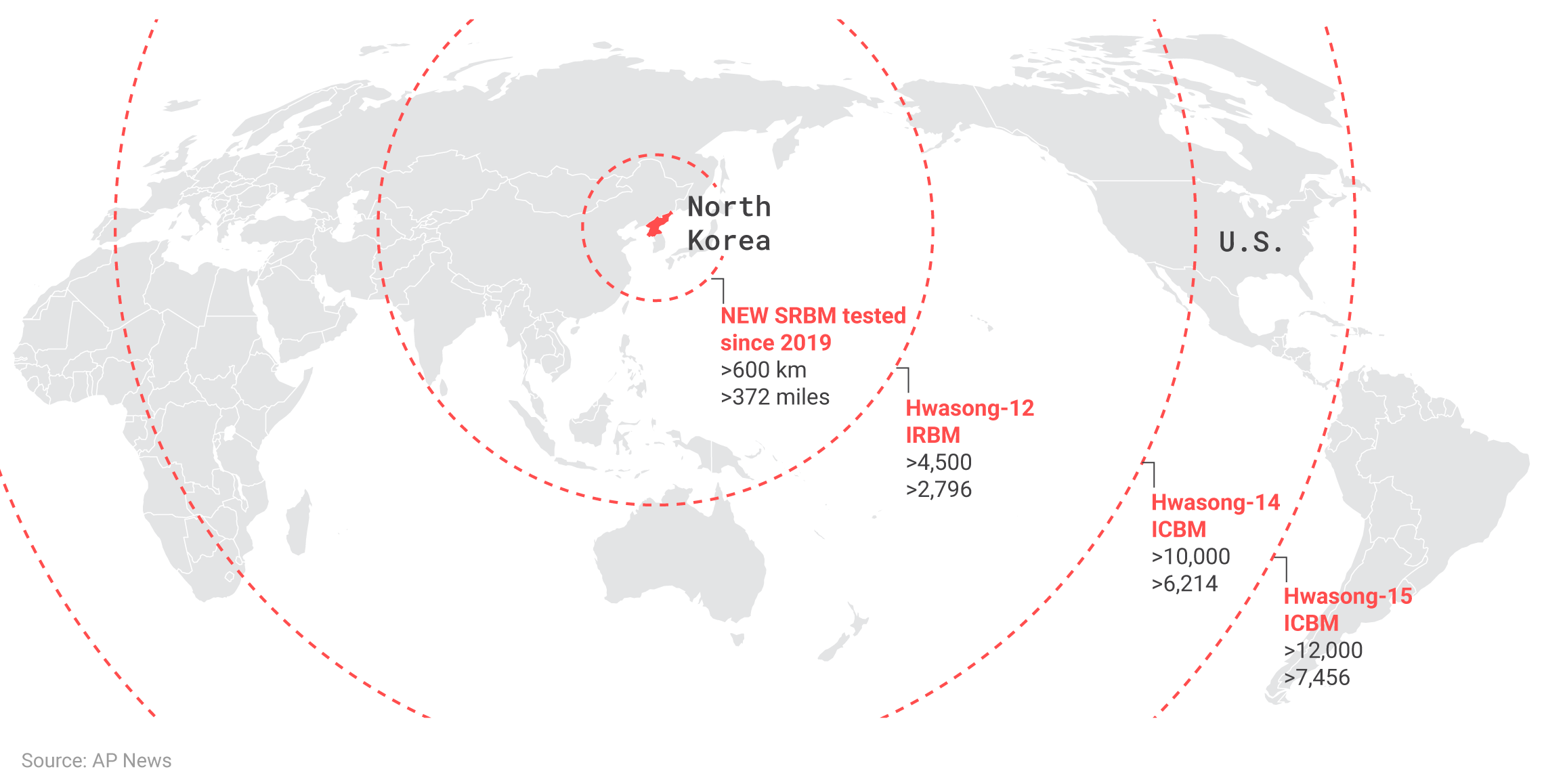

Estimated ranges of North Korea’s missile arsenal

North Korea possesses the capability to launch nuclear strikes against U.S. forces in Asia, as well as the continental United States itself. Therefore, a war on the Korean Peninsula would likely place the U.S. homeland at risk.

Statements about the “denuclearization” of the peninsula, which is still official U.S. policy according to Biden administration documents,43U.S. Department of Defense, 2022 National Defense Strategy, Nuclear Posture Review, and Missile Defense Review, (Washington, DC: Department of Defense 2022), https://media.defense.gov/2022/Oct/27/2003103845/-1/-1/1/2022-NATIONAL-DEFENSE-STRATEGY-NPR-MDR.PDF. are getting more unrealistic and unhelpful by the day. Instead, U.S.-North Korea policy should accept the twin realities that (1) the United States and North Korea are in a state of mutual deterrence based on mutual vulnerability, and (2) North Korea is exceedingly unlikely to dismantle its nuclear weapons program any time soon. Therefore, efforts to coerce North Korea into disarming will fail and, under certain scenarios, could potentially worsen security in the region and endanger the United States and its allies by convincing Pyongyang that war is unavoidable.

A more reasonable response would resemble other tried-and-true approaches of the nuclear age: deterrence and arms control rather than preemption and denuclearization. Arms control, broadly understood to include risk reduction and transparency measures in addition to weapons counts, could find a warmer audience in Pyongyang than one might expect, partly because it would imply acceptance of North Korea’s nuclear arsenal.44Manseok Lee, “Time to Pursue Arms Control With North Korea,” Diplomat, October 26, 2021, https://thediplomat.com/2021/10/time-to-pursue-arms-control-with-north-korea/. It could also lower the temperature and provide a basis for more stable and predictable relations between the United States and North Korea.45Jeffrey Lewis, “It’s Time to Accept That North Korea Has Nuclear Weapons,” New York Times, October 13, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/13/opinion/international-world/north-korea-us-nuclear.html. Finally, it could open the door for an easing of sanctions, which often hurt ordinary citizens and hamper the delivery of humanitarian aid.46“What to Know About Sanctions on North Korea,” Council on Foreign Relations, July 27, 2022, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/north-korea-sanctions-un-nuclear-weapons.

Some U.S. officials have made noise about beginning an arms control dialogue only to be silenced or overruled by others in the Biden administration.47David Brunnstrom and Simon Lewis, “U.S. Says North Korea Policy Unchanged after Nuclear Remark Raises Eyebrows,” Reuters, October 29, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/us-says-north-korea-policy-unchanged-after-nuclear-remark-raises-eyebrows-2022-10-29/. But advocates of denuclearization policy must explain why the same tired combination of tightened sanctions, joint military exercises, and pronouncements about the illegality of North Korean nuclear weapons will finally start working. A policy that more closely reflects the reality of a nuclear North Korea is the safer, more stable option and the best one available for the United States.

The age of restraint

The year after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Bernard Brodie famously wrote, “Thus far the chief purpose of military establishment has been to win wars. From now on its chief purpose must be to avert them. It can have almost no other useful purpose.”48Bernard Brodie, “Part I: The Weapon,” in Brodie, ed., The Absolute Weapon, 76. Though Brodie noted that previous military inventions eventually led to adjustments that did not radically alter the nature of war, “The factor of increase of destructive efficiency is so great that . . . the experience of the past concerning eventual adjustment might just as well be thrown out the window.”49Bernard Brodie, “Part I: The Weapon,” in Brodie, ed., The Absolute Weapon, 34.

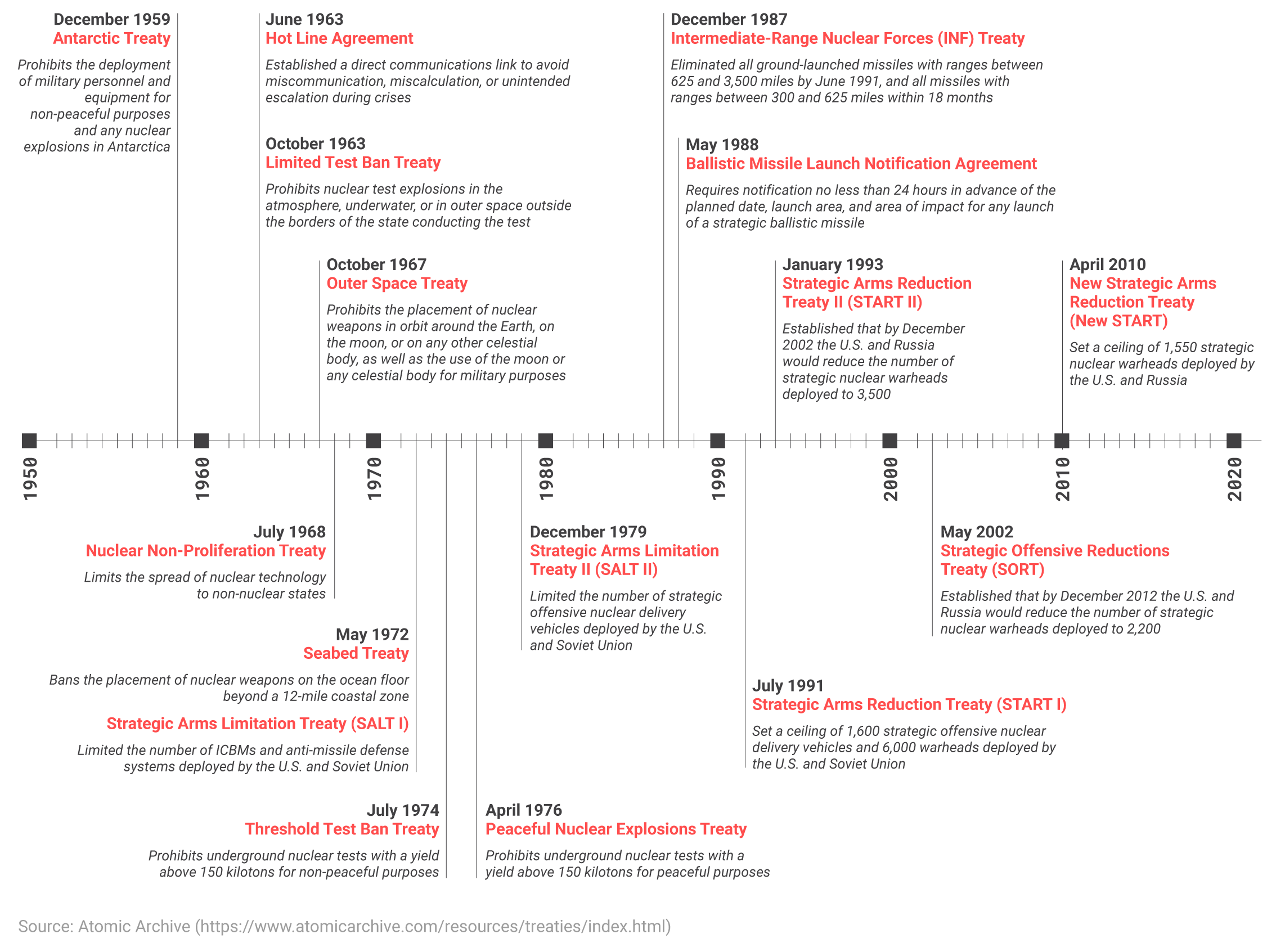

Timeline of major arms control treaties

Even though they were rivals, the United States and Soviet Union used arms control to manage strategic competition throughout the Cold War. Arms control diplomacy continued after the Cold War, as the United States and Russia dramatically reduced the size of their nuclear arsenals.

The nuclear age is fundamentally an age of restraint; one where states are reluctant to go to war for fear of the terrible consequences. In most imaginable nuclear wars, “victory” has little discernable meaning. Deterrence endures, and recent technological innovations have not significantly changed political leaders’ risk calculus. Leaders continue to treat nuclear weapons differently, further enhancing deterrence.

To say nuclear use is unlikely is not to say it is impossible. But old policy tools can still be useful. Threats that leave something to chance can deter without cornering the threatener into acting. Arms control can build cooperation based on an implicit acknowledgment of mutual vulnerability.

These policies can guide the United States’ approach to China’s nuclear build-up, a challenge that will likely get more difficult in the coming years. China, long a model of nuclear moderation, has now developed or is planning to develop additional warheads, new missile silos, and a delivery system that uses a low Earth orbiting vehicle to evade missile defenses. It may sound scary, but one must remember that China has the same tall order as North Korea: trying to deter a rival that still spends considerably more on defense and has more nuclear options. China’s nuclear development is likely an effort to keep a U.S.-China war unthinkable, especially in the minds of U.S. leaders.50Fiona Cunningham and M. Taylor Fravel, “China’s Nuclear Arsenal Is Growing. What Does That Mean for U.S.-China Relations?,” Washington Post, November 11, 2021, http://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/11/11/chinas-nuclear-arsenal-is-growing-what-does-that-mean-us-china-relations/; Lyle Goldstein, “Raising the Minimum: Explaining China’s Nuclear Buildup,” Defense Priorities, April 5, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/raising-the-minimum-explaining-chinas-nuclear-buildup. For the sake of millions, U.S. leadership should indulge the Chinese on this crucial point.

Despite some inconsistencies, strategic ambiguity has already served the United States well over the past few decades in keeping Taiwan safe without provoking China. Arms control has been a tougher sell in Beijing, perhaps understandably, given China’s lack of nuclear parity with the United States and Russia. Since February 2022, the latter two countries have shown the value of communication in crises even as other pieces of their bilateral arms control architecture have been crumbling: U.S. and Russian officials reportedly met secretly to manage escalation and avoid nuclear confrontation over Ukraine.51Vivian Salama and Michael R. Gordon, “Senior White House Official Involved in Undisclosed Talks With Top Putin Aides,” Wall Street Journal, November 7, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/senior-white-house-official-involved-in-undisclosed-talks-with-top-putin-aides-11667768988. A long-standing tradition of nuclear dialogue between the two sides may deserve some credit for keeping communication channels open even as they find themselves on opposing sides of the war. Hopefully, China sees the value in the escalation management side of arms control.

In at least one important sense, U.S.-China arms control talks already received a boost when the two countries joined the other permanent United Nations Security Council members to declare, echoing President Ronald Reagan and Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev, that a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought.52The White House, “Joint Statement of the Leaders of the Five Nuclear-Weapon States on Preventing Nuclear War and Avoiding Arms Races,” January 3, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/01/03/p5-statement-on-preventing-nuclear-war-and-avoiding-arms-races/. The pronouncement acknowledged the mutual vulnerability at the heart of the nuclear revolution and provides a simple basis for building higher levels of cooperation. This mutual vulnerability will persist no matter who has an edge in various other technological fields or how sharp the photos of ballistic missile sites taken from the altitude of a spy balloon are. Despite our differences—and the United States and China have significant ones—in the face of nuclear war, all of humanity is on the same side.

Endnotes

- 1Bernard Brodie, ed., The Absolute Weapon: Atomic Power and World Order (New York: Harcourt, Brace, and Company, 1946).

- 2Robert Jervis, The Meaning of the Nuclear Revolution: Statecraft and the Prospect of Armageddon, Cornell Studies in Security Affairs (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1990).

- 3Robert Jervis, “The Nuclear Revolution and the Common Defense,” Political Science Quarterly 101, no. 5 (1986): 690.

- 4Nina Tannenwald, The Nuclear Taboo: The United States and the Non-Use of Nuclear Weapons Since 1945 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007); Thomas C. Schelling, “An Astonishing 60 Years: The Legacy of Hiroshima,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103, no. 16 (2006): 6089–93.

- 5See the abstract for Keir A. Lieber and Daryl G. Press, “The New Era of Counterforce: Technological Change and the Future of Nuclear Deterrence,” International Security 41, no. 4 (April 2017): 9–49.

- 6Vipin Narang, “Why Kim Jong Un Wouldn’t Be Irrational to Use a Nuclear Bomb First,” Washington Post, September 8, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/why-kim-jong-un-wouldnt-be-irrational-to-use-a-nuclear-bomb-first/2017/09/08/a9d36ca4-934f-11e7-aace-04b862b2b3f3_story.html.

- 7Austin Long and Brendan Rittenhouse Green, “Stalking the Secure Second Strike: Intelligence, Counterforce, and Nuclear Strategy,” Journal of Strategic Studies 38, no. 1–2 (2015): 38–73.

- 8Lieber and Press, “The New Era of Counterforce”; Keir A. Lieber and Daryl G. Press, The Myth of the Nuclear Revolution: Power Politics in the Atomic Age (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2020); Andrew Futter, “Deterrence, Disruptive Technology and Disarmament in the Third Nuclear Age,” Hiroshima Organisation for Global Peace, April 2022, https://hiroshimaforpeace.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Deterrence-Disruptive-Technology-and-Disarmament-in-the-Third-Nuclear-Age.pdf.

- 9Narang, “Why Kim Jong Un Wouldn’t Be Irrational to Use a Nuclear Bomb First.”

- 10Caitlin Talmadge, “What Putin’s Nuclear Threats Mean for the U.S.,” Wall Street Journal, March 3, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/what-putins-nuclear-threats-mean-for-the-u-s-11646329125.

- 11Vipin Narang and Scott D. Sagan, eds., The Fragile Balance of Terror: Deterrence in the New Nuclear Age (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2023), 2.

- 12For a recent piece contending on more technical grounds that survivability is still running ahead of developments in counterforce, see Christopher Clary, “Survivability in the New Era of Counterforce,” The Fragile Balance of Terror: Deterrence in the New Nuclear Age, ed. Vipin Narang and Scott D. Sagan (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2023), 154–81.

- 13To see how the Cuban Missile Crisis fits this characterization, see Serhii Plokhy, Nuclear Folly: A History of the Cuban Missile Crisis (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2021).

- 14For a Cold War-era argument that nuclear deterrence is “not so difficult,” see Robert Jervis, The Illogic of American Nuclear Strategy (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1984).

- 15Michèle A. Flournoy, “How to Prevent a War in Asia,” Foreign Affairs, June 18, 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-06-18/how-prevent-war-asia. See also Eric Schmidt and Robert O. Work, “How to Stop the Next World War,” Atlantic, December 5, 2022, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/12/us-china-military-rivalry-great-power-war/672345/.

- 16Mark B. Schneider, “Countering Putin’s Nuclear Threats,” RealClearDefense, July 6, 2022, https://www.realcleardefense.com/articles/2022/07/06/countering_putins_nuclear_threats_840988.html; Nadia Schadlow, “Why Deterrence Failed Against Russia,” Wall Street Journal, March 20, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/why-u-s-deterrence-failed-ukraine-putin-military-defense-11647794454; Mike Gallagher, “Biden’s ‘Integrated Deterrence’ Fails in Ukraine,” Wall Street Journal, March 29, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/biden-integrated-deterrence-fails-ukraine-russia-invasion-taiwan-xi-china-diplomacy-sanctions-hard-power-defense-spending-budget-negotiations-11648569487; Liam Collins and Frank Sobchak, “U.S. Deterrence Failed in Ukraine,” Foreign Policy, February 20, 2023, https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/02/20/ukraine-deterrence-failed-putin-invasion/.

- 17“Nuclear Weapons: Who Has What at a Glance,” Arms Control Association, January 2022, https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/Nuclearweaponswhohaswhat.

- 18Giulia Carbonaro, “Risk of Nuclear Conflict at Highest Point Since Height of Cold War—SIPRI,” Newsweek, June 13, 2022, https://www.newsweek.com/risk-nuclear-conflict-highest-point-since-height-cold-war-sipri-1715161; Alvin Powell, “60 Years After Cuban Missile Crisis, Nuclear Threat Feels Chillingly Immediate,” Harvard Gazette, October 17, 2022, https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2022/10/sixty-years-after-cuban-missile-crisis-nuclear-threat-feels-chillingly-immediate/; Daniel de Visé, “Americans’ Nuclear Fears Surge to Highest Levels since Cold War,” Hill, October 14, 2022, https://thehill.com/policy/defense/3687396-americans-nuclear-fears-surge-to-highest-levels-since-cold-war/.

- 19Collin Meisel, “Failures in the ‘Deterrence Failure’ Dialogue,” War on the Rocks, May 8, 2023, https://warontherocks.com/2023/05/failures-in-the-deterrence-failure-dialogue/.

- 20Emma Ashford and Joshua Shifrinson, “How the War in Ukraine Could Get Much Worse,” Foreign Affairs, March 8, 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/ukraine/2022-03-08/how-war-ukraine-could-get-much-worse.

- 21David Herszenhorn and Giorgio Leali, “Defiant Putin Mauls Macron in Moscow,” Politico, February 7, 2022, https://www.politico.eu/article/vladimir-putin-russia-welcomes-emmanuel-macron-france-into-his-lair-kremlin-ukraine/.

- 22Reid Pauly, “The Tangled Fates of Pittsburgh and Paris,” War on the Rocks, June 12, 2017, https://warontherocks.com/2017/06/the-tangled-fates-of-pittsburgh-and-paris/.

- 23Vivienne Machi, “Inside the Multinational Logistics Cell Coordinating Military Aid for Ukraine,” Defense News, July 21, 2022, https://www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2022/07/21/inside-the-multinational-logistics-cell-coordinating-military-aid-for-ukraine/.

- 24Helene Cooper, Julian E. Barnes, and Eric Schmitt, “Russian Military Leaders Discussed Use of Nuclear Weapons, U.S. Officials Say,” New York Times, November 2, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/02/us/politics/russia-ukraine-nuclear-weapons.html.

- 25On how the chemical weapons taboo has weathered violations, see: Richard Price, “How Chemical Weapons Became Taboo,” Foreign Affairs, January 22, 2013, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/syria/2013-01-22/how-chemical-weapons-became-taboo.

- 26Thomas C. Schelling, The Strategy of Conflict (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1960).

- 27Richard K. Betts, Nuclear Blackmail and Nuclear Balance (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 1987), 13.

- 28David E. Sanger et al., “U.S. Makes Contingency Plans in Case Russia Uses Its Most Powerful Weapons,” New York Times, March 23, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/23/us/politics/biden-russia-nuclear-weapons.html.

- 29Sam Fossum, Kaitlan Collins, and Paul LeBlanc, “Biden Offers Stark ‘Armageddon’ Warning on the Dangers of Putin’s Nuclear Threats,” CNN, October 7, 2022, https://www.cnn.com/2022/10/06/politics/armageddon-biden-putin-russia-nuclear-threats/index.html.

- 30Robert Axelrod, The Evolution of Cooperation (New York: Basic Books, 1984).

- 31Deterrence is not the only conceivable reason for Russian nuclear restraint. For example, William Alberque argues that lack of suitable targets for Russian nuclear use and potential alienation of India and China (an indicator that the nuclear use taboo may still be having an effect) are also key factors. Still, Alberque also repeatedly mentions the “threat of intervention and escalation” by NATO as another plausible reason for Russian nuclear nonuse. See William Alberque, “Russia Is Unlikely to Use Nuclear Weapons in Ukraine,” International Institute for Strategic Studies, October 10, 2022, https://www.iiss.org/blogs/analysis/2022/10/russia-is-unlikely-to-use-nuclear-weapons-in-ukraine.

- 32Choe Sang-Hun, “North Korea Launches 23 Missiles, Triggering Air-Raid Alarm in South,” New York Times, November 2, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/01/world/asia/north-korea-missile-launch.html; Motoko Rich and Choe Sang-Hun, “North Korea Fires Powerful Missile, Using Old Playbook in a New World,” New York Times, October 3, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/03/world/asia/japan-north-korea-missile.html.

- 33Doina Chiacu and David Brunnstrom, “North Korea Demands the U.S., South Korea Halt Joint Military Drills,” Reuters, October 31, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/north-korea-calls-united-states-south-korea-stop-joint-military-exercises-2022-10-31/; Josh Smith, “U.S. Helicopters Hold First Live-Fire Drills in South Korea since 2019,” Reuters, July 25, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/us-helicopters-hold-first-live-fire-drills-skorea-since-2019-2022-07-25/.

- 34Jordan Bernhardt and Lauren Sukin, “Joint Military Exercises and Crisis Dynamics on the Korean Peninsula,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 65, no. 5 (November 2020): 863.

- 35Jessie Yeung, Paula Hancocks, and Yoonjung Seo, “Why Is North Korea Firing so Many Missiles—and Should the West Be Worried?,” CNN, October 8, 2022, https://www.cnn.com/2022/10/07/asia/north-korea-missile-testing-frequency-explainer-intl-hnk/index.html.

- 36Peter Bergen, “The Generals Tried to Keep Trump in Check. What Happens to Foreign Policy Now That They’ve Left?,” TIME, December 5, 2019, https://time.com/5744414/trump-generals-military-experience/.

- 37Hearing on National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018 and Oversight of Previously Authorized Programs, United States House of Representatives, 115 Cong. 1 (2017), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-115hhrg26739/html/CHRG-115hhrg26739.htm.

- 38Nahal Toosi, “Dunford: Military Option for North Korea Not ‘Unimaginable,’” Politico, July 22, 2017, https://www.politico.com/story/2017/07/22/dunford-north-korea-military-option-not-unimaginable-240851.

- 39“2nd Harvard Korean Security Summit: ‘Korea—An Oracle of Global Trends,’” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, February 10, 2021, https://www.belfercenter.org/event/2nd-harvard-korean-security-summit-korea-oracle-global-trends.

- 40Sofio Lotto Persio, “North Korea Threatens to Strike U.S. With ‘Powerful Nuclear Hammer,’” Newsweek, July 25, 2017, https://www.newsweek.com/north-korea-threatens-strike-us-heart-powerful-nuclear-hammer-honed-and-641482.

- 41Evan Osnos, “The Risk of Nuclear War with North Korea,” New Yorker, September 7, 2017, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/09/18/the-risk-of-nuclear-war-with-north-korea.

- 42Robert Kuttner, “Steve Bannon, Unrepentant,” American Prospect, August 16, 2017, https://prospect.org/api/content/d18c3f64-4596-5ac2-b9e2-3d47df0be592/. Emphasis added.

- 43U.S. Department of Defense, 2022 National Defense Strategy, Nuclear Posture Review, and Missile Defense Review, (Washington, DC: Department of Defense 2022), https://media.defense.gov/2022/Oct/27/2003103845/-1/-1/1/2022-NATIONAL-DEFENSE-STRATEGY-NPR-MDR.PDF.

- 44Manseok Lee, “Time to Pursue Arms Control With North Korea,” Diplomat, October 26, 2021, https://thediplomat.com/2021/10/time-to-pursue-arms-control-with-north-korea/.

- 45Jeffrey Lewis, “It’s Time to Accept That North Korea Has Nuclear Weapons,” New York Times, October 13, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/13/opinion/international-world/north-korea-us-nuclear.html.

- 46“What to Know About Sanctions on North Korea,” Council on Foreign Relations, July 27, 2022, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/north-korea-sanctions-un-nuclear-weapons.

- 47David Brunnstrom and Simon Lewis, “U.S. Says North Korea Policy Unchanged after Nuclear Remark Raises Eyebrows,” Reuters, October 29, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/us-says-north-korea-policy-unchanged-after-nuclear-remark-raises-eyebrows-2022-10-29/.

- 48Bernard Brodie, “Part I: The Weapon,” in Brodie, ed., The Absolute Weapon, 76.

- 49Bernard Brodie, “Part I: The Weapon,” in Brodie, ed., The Absolute Weapon, 34.

- 50Fiona Cunningham and M. Taylor Fravel, “China’s Nuclear Arsenal Is Growing. What Does That Mean for U.S.-China Relations?,” Washington Post, November 11, 2021, http://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/11/11/chinas-nuclear-arsenal-is-growing-what-does-that-mean-us-china-relations/; Lyle Goldstein, “Raising the Minimum: Explaining China’s Nuclear Buildup,” Defense Priorities, April 5, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/raising-the-minimum-explaining-chinas-nuclear-buildup.

- 51Vivian Salama and Michael R. Gordon, “Senior White House Official Involved in Undisclosed Talks With Top Putin Aides,” Wall Street Journal, November 7, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/senior-white-house-official-involved-in-undisclosed-talks-with-top-putin-aides-11667768988.

- 52The White House, “Joint Statement of the Leaders of the Five Nuclear-Weapon States on Preventing Nuclear War and Avoiding Arms Races,” January 3, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/01/03/p5-statement-on-preventing-nuclear-war-and-avoiding-arms-races/.

More on Asia

Featuring Jennifer Kavanagh

October 4, 2025

Featuring Jennifer Kavanagh

September 29, 2025