December 8, 2021

The folly of a democracy-based grand strategy

Key points

- President Biden’s Summit for Democracy exacerbates regime security fears in states such as Russia and China, further destabilizing relations and making it more difficult to advance U.S. interests.

- U.S. policymakers may claim democracy promotion and regime change are clearly different policies. But years of excessive pursuit of both to prop up U.S. hegemony mean Russia, China, and other non-democracies perceive them as part of a unified U.S. threat to their regimes.

- China and Russia’s fears for their regime security may be overwrought, but regardless, they encourage those states to collaborate more with each other; resist diplomacy with the United States on other issues, such as arms control; and crack down on dissidents and civil society. Viewing U.S.-backed democracy promotion as a tool of regime change, China and Russia do more to suppress democracy at home and work to undermine it abroad.

- The U.S. alleviating all of China and Russia’s apparent concerns is impossible and unnecessary; indeed, some regime insecurity is welcome for its restraining influence. But to advance its own interests, the United States should find ways to diminish piqued regime security fears.

- To reduce regime security fears, especially in China and Russia, the United States should separate democracy promotion from its grand strategy—democracy promotion is not a security priority. Democracy promotion is good but starts at home, by being an exemplar of liberal values.

A “Summit for Democracy” sounds good but is counterproductive

The Biden administration’s virtual Summit for Democracy beginning December 9 with 111 other countries and governments has the stated goal to “defend democracy and human rights at home and abroad.”1“The Summit for Democracy,” U.S. Department of State, accessed December 7, 2021, https://www.state.gov/summit-for-democracy/. While echoing the famous call to “make the world safe for democracy,”2Tony Smith, “Making the World Safe for Democracy in the American Century,” Diplomatic History volume 23, number 2 (1999): 173–188. the summit follows the Biden administration’s push to emphasize democratic renewal as a key feature in its national security strategy.3Joseph R. Biden Jr., “Why American Must Lead Again: Recusing U.S. Foreign Policy after Trump.” Foreign Affairs, March/April 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-01-23/why-america-must-lead-again.

This emphasis marks a shift from the rhetoric of the Trump administration, but it fits squarely in a U.S. foreign policy tradition going back decades.4Tony Smith, America’s Mission: The United States and the Worldwide Struggle for Democracy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995); Michael C. Desch, “America’s Liberal Illiberalism: The Ideological Origins of Overreaction in U.S. Foreign Policy,” International Security 32, no. 3 (2007): 7–43. Skeptics of the summit note it will likely fail to attain any tangible goals, but advocates hope it will produce concrete action, including steps to promote democracy in Russia and China.5Madeleine K. Albright, “The Coming Democratic Revival,” Foreign Affairs, November/December 2021, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/world/2021-10-19/madeleine-albright-coming-democratic-revival; Nahal Toosi, “An ‘Illustrative Menu of Options,’” Politico, November 4, 2021, https://www.politico.com/news/2021/11/04/biden-democracy-summit-technology-519530; Richard Fontaine and Jared Cohen, “Biden’s Democracy Summit Needs to Produce More Than a Bland Statement,” Foreign Policy, November 12, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/11/12/biden-democracy-summit-china-russia-authoritarianism/; Anne Applebaum, “The Bad Guys Are Winning,” Atlantic, November 15, 2021, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2021/12/the-autocrats-are-winning/620526/.

There has been much haggling over which countries the Biden administration invited to the summit but less attention on the broader effects this summit might have on U.S. interests. There is a surprising lack of consideration of what China and Russia, among others, see lurking behind the renewed U.S. emphasis on democracy globally. Already, both countries have cautioned the Biden administration against the summit, saying a foreign policy focused on “spreading ‘democracy’ and values against other countries’ preferences will severely undermine regional and international peace, security, and stability.”6Anatoly Antonov and Qin Gang, “Russian and Chinese Ambassadors: Respecting People’s Democratic Rights,” National Interest, November 26, 2021, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/russian-chinese-ambassadors-respecting-people%E2%80%99s-democratic-rights-197165.

While most of the positive movement that comes out of this summit will likely be symbolic, the downsides of emphasizing democracy promotion in U.S. foreign policy could have real and dangerous effects. Revitalizing American democracy should remain a domestic priority. But promoting global democracy as a top foreign policy priority, other than by being an exemplar, achieves nothing concrete while giving credence to China and Russia’s fears about U.S. regime change efforts, making it harder to advance U.S. interests with those influential states.

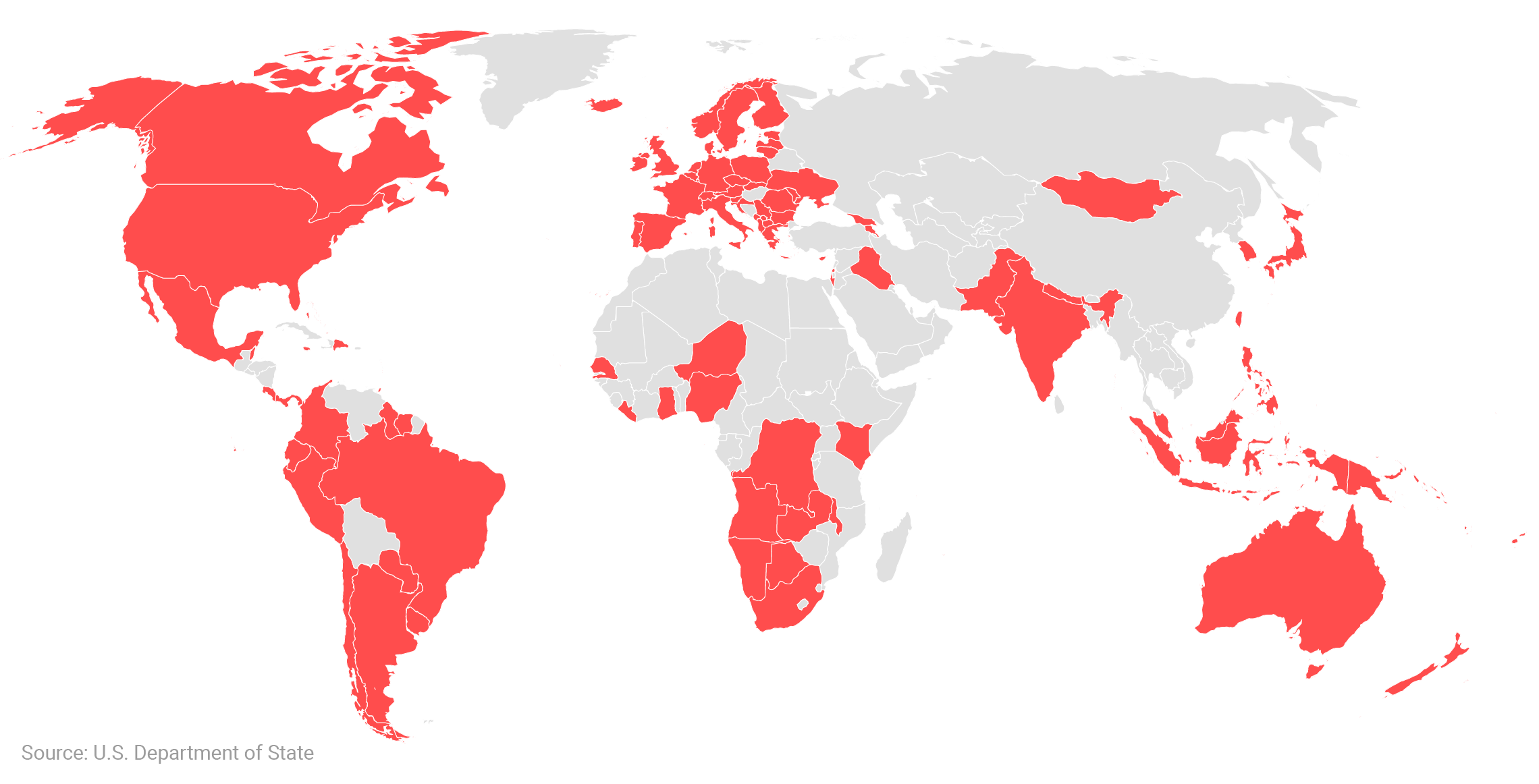

Countries and governments invited to the 2021 Summit for Democracy

The United States invited 111 participants to a two-day virtual summit starting December 9, 2021.

Why states fear for regime security

Regime security refers to maintaining control over who or what authority rules in a state. While often overlooked, regime security is as vital as traditional territorial security to most states. The issue is often discussed in terms of internal threats, like coups or popular uprisings, but external threats to regime security are often even more menacing. And when external actors combine with internal forces to threaten regime security, the regime is under extreme pressure to preserve its rule and remove opportunities for external influence. Eliminating regime insecurity is impossible, and indeed some insecurity is inevitable and welcome as a restraining force. But too much insecurity, especially from external sources, can push regimes to look for ways to improve their safety, such as by suppressing democracy at home and increasing hostility abroad to counter countries seeking regime change. In other words, aggressive democracy promotion, by triggering regime insecurity in autocracies, can encourage repression and aggression.

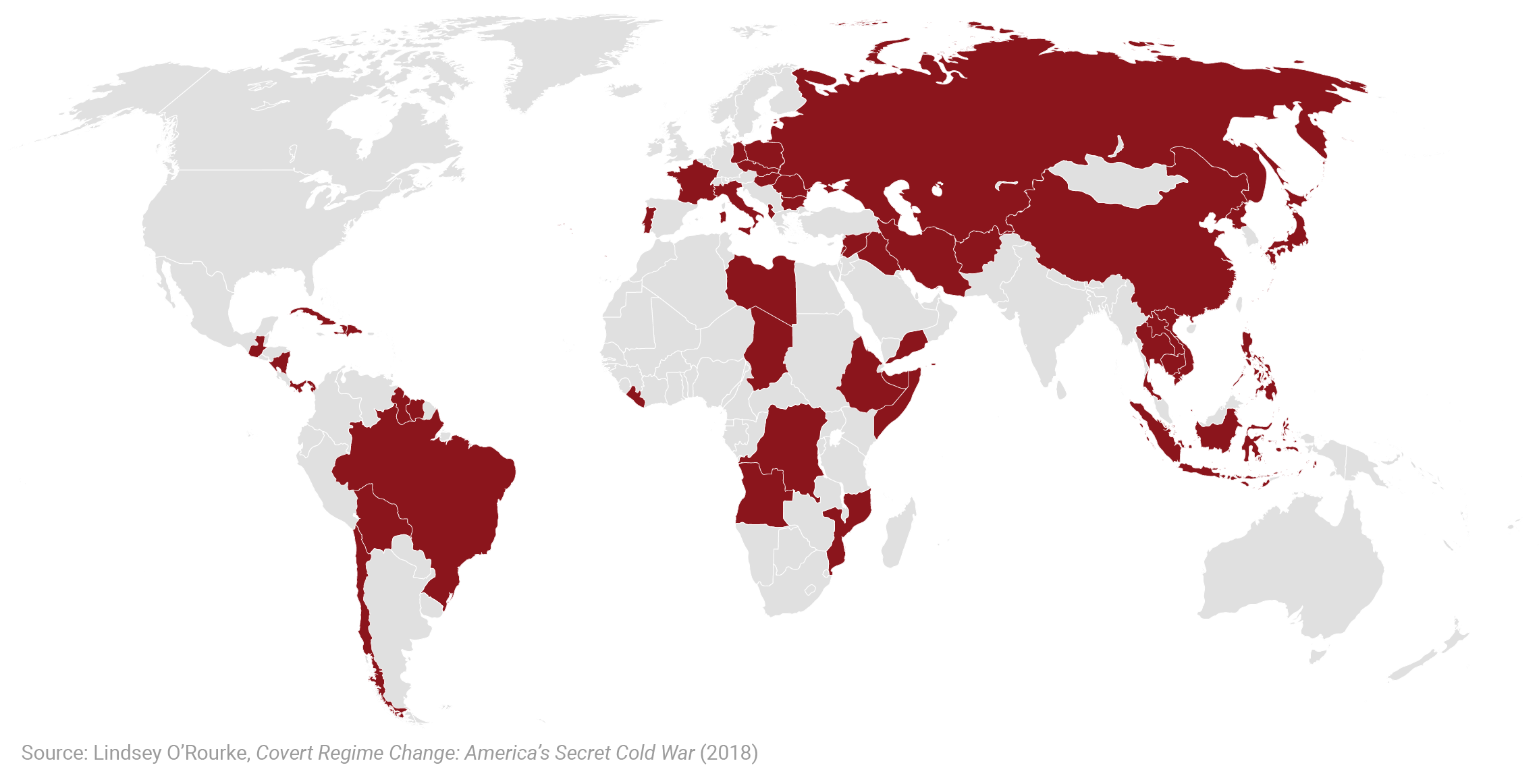

A dominant feature of U.S. foreign policy for decades has been its interest in threatening the regime security of various states through regime change, democracy promotion, and electoral interference.7Lindsey A. O’Rourke, Covert Regime Change: America’s Secret Cold War (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2018); Dov H. Levin, Meddling in the Ballot Box: The Causes and Effects of Partisan Electoral Interventions (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020); John M. Owen, “The Foreign Imposition of Domestic Institutions,” International Organization 56, no. 2 (2002): 375–409. Whether through intervening in Haiti and the Dominican Republic under Woodrow Wilson, interfering in Italian elections during the early Cold War, or aiding coups in Guatemala and Iran, the United States has been remarkably consistent in pursuing regime change over the past century. Sadly, even when “successful,” these efforts often unleash disastrous side effects, including harm to regional stability, human rights, and democracy.8Benjamin Denison, “The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same: The Failure of Regime‐Change Operations,” Cato Institute, January 6, 2020, https://www.cato.org/policy-analysis/more-things-change-more-they-stay-same-failure-regime-change-operations.

Since the Cold War, U.S. grand strategy sought democratic expansion around the world to promote American primacy.9Barry Posen defines “grand strategy” as “a political-military means-ends chain, a state’s theory about how it can best ‘cause’ security for itself.” See Barry R. Posen, The Sources of Military Doctrine: France, Britain, and Germany Between the World Wars (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1984): 13; “ William J. Clinton, A National Security Strategy of Engagement and Enlargement (Washington: White House, 1994), http://nssarchive.us/NSSR/1994.pdf; George W. Bush, The National Security Strategy of the United States of America (Washington: White House, 2002), http://nssarchive.us/NSSR/2002.pdf; Barack Obama, National Security Strategy of the United States of America (Washington: White House, 2010), http://nssarchive.us/NSSR/2010.pdf. This manifested through alliance conditionality, civil society support, and direct military action to expand democracy and advance U.S. primacy. In the 1990s, advocates of the United States promoting democracy abroad argued a larger community of democracies would support U.S. interests and continued American hegemonic power. As the Clinton National Security Strategy (NSS), published in 1994, articulated it, “All of America’s strategic interests—from promoting prosperity at home to checking global threats abroad before they threaten our territory—are served by enlarging the community of democratic and free market nations.”10William J. Clinton, A National Security Strategy of Engagement and Enlargement.

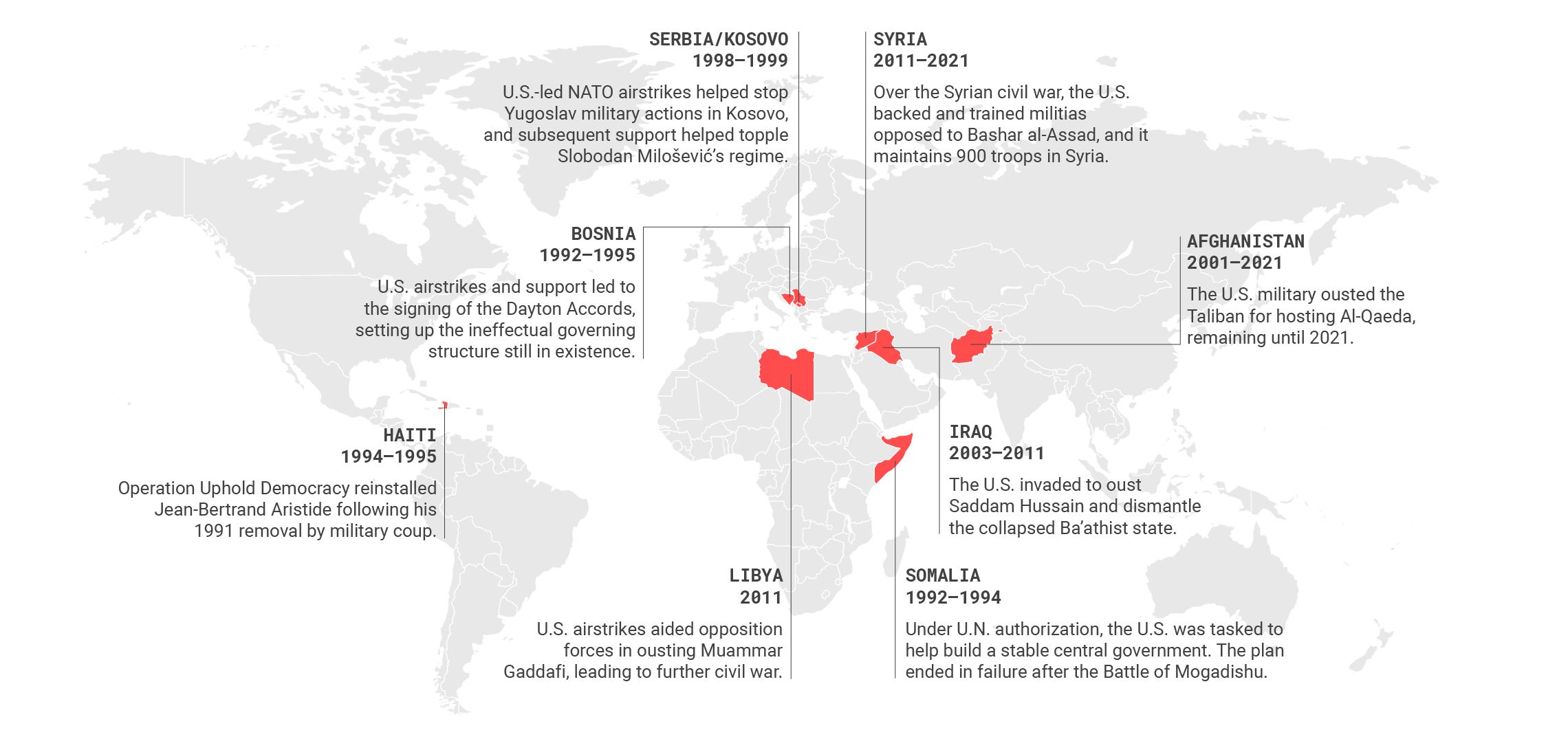

The United States promoted democracy through military interventions, such as in the former Yugoslavia, Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, and elsewhere. But it also did so in other ways, most prominently through non-military democracy promotion abroad. The primary tools of democracy promotion were funding overseas civil society groups, backing popular protests within foreign countries, and using the carrot of alliance expansion to influence foreign governments. Overthrowing existing non-democratic regimes with political tools was often preferable to military intervention for spreading democracy, but the sword remained ready.11Seva Gunitsky, Aftershocks (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017): 198–230.

Countries targeted for U.S.-backed regime change attempts during the Cold War

The United States planned and carried out dozens of covert and overt regime change campaigns between 1947 and 1989, according to research by Lindsey O’Rourke of Boston College.

While democratic expansion continued throughout the Clinton, Bush, and Obama administrations, and even during the Trump administration, the United States regularly threatened to change regimes it disagreed with and encouraged domestic opposition groups. In the last administration alone, the “maximum pressure” campaign against Iran, the North Korean nuclear talks, the Venezuelan election crisis, and regular comments about China by U.S. officials all referenced the nefariousness of their regimes and a desire for an alternative.12“Transcript: Mike Pompeo talks with Michael Morell on “Intelligence Matters,” CBS News, May 1, 2019, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/transcript-mike-pompeo-talks-with-michael-morell-on-intelligence-matters/; Elliott Abrams, “A New Path to Venezuelan Democracy, Wall Street Journal, March 31, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/a-new-path-to-venezuelan-democracy-11585645210; Kate O’Keeffe and William Mauldin, “Mike Pompeo Urges Chinese People to Change Communist Party,” Wall Street Journal, July 23, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/secretary-of-state-pompeo-to-urge-chinese-people-to-change-the-communist-party-11595517729; “Trump Should Insist on Libya-Style Denuclearization for North Korea: Bolton,” Reuters, March 23, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-trump-bolton-northkorea/trump-should-insist-on-libya-style-denuclearization-for-north-korea-bolton-idUSKBN1GZ37A. The persistent discussion of regime change continued to make democracy synonymous with a pro-U.S. orientation and raised regime security fears of various states.

Years of U.S.-led regime change and democracy promotion have fostered fears today among various non-democratic foreign leaders that the United States is actively undermining their power or seeking to overthrow them. Even where leaders’ concerns about regime change are overwrought, decades of U.S. actions abroad lend credence to their fears.

Regime security fears today in China and Russia

Since the end of the Cold War, China and Russia have witnessed the United States use democracy promotion efforts as instruments to topple foreign leaders they dislike, such as during the so-called “color revolutions” and the Arab Spring.13In Russian official discourse, there is an assumption that the United States was largely behind the “Color Revolutions” in their near abroad. See Jeanne L. Wilson, “The Legacy of the Color Revolutions for Russian Politics and Foreign Policy,” Problems of Post-Communism volume 57, issue 2 (2010): 21–36; Yulia Nikitinа, “The ‘Color Revolutions’ and ‘Arab Spring’ in Russian Official Discourse,” Connections volume 14, number 1 (2014): 87–104; Kimberly Marten, “Putin’s Choices: Explaining Russian Foreign Policy and Intervention in Ukraine,” Washington Quarterly volume 38, number 2 (April 2015): 189–204. Similarly, Chinese discourse has also framed color revolutions abroad as driven by the United States to uphold their strategic interests. See Andrew J. Nathan and Andrew Scobell, “How China Sees America: The Sum of Beijing,” Foreign Affairs Volume 91, number 1 (2012): 32–47; Karrie J. Koesel and Valerie J. Bunce, “Diffusion-Proofing: Russian and Chinese Responses to Waves of Popular Mobilizations against Authoritarian Rulers,” Perspectives on Politics volume 11, number 3 (September 2013): 753–68; Titus C. Chen, “China’s Reaction to the Color Revolutions: Adaptive Authoritarianism in Full Swing,” Asian Perspective volume 34, number 2 (2010): 5–51. When popular protests appear now, the worry is the United States will intervene to support the protestors against the regime.

This U.S. playbook drives anxieties in China and Russia—namely that the United States will use democracy promotion efforts to create protest movements that they will then intervene to aid. U.S. policymakers insist democracy promotion and regime change by intervention are clearly distinct and separate tools. China, Russia, and other non-democratic regimes think differently. They view each as a variation on the same regime-threatening theme.

Major U.S. regime change campaigns since the Cold War

Leaders of non-democratic nations have witnessed overt U.S.-led regime change efforts in the last 30 years, which has increased regime insecurity. Even powerful nations, like China and Russia, fear they are targets of military or non-military intervention efforts to undermine their hold on power.

In both Beijing and Moscow, official documents discuss fears of American interference. Threats against regime security are repeatedly discussed as a core national challenge. The 2015 Chinese military strategy states, “anti-China forces have never given up their attempt to instigate a ‘color revolution’ in this country.”14“China’s Military Strategy,” Ministry of National Defense of the People’s Republic of China, May 26, 2015, http://eng.mod.gov.cn/Press/2015-05/26/content_4586805.htm. Russia’s 2015 national security strategy listed the same concerns as a core security threat.15Stephanie Pezard and Ashley L. Rhoades, “What Provokes Putin’s Russia?” RAND Corporation, January 2020, https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PE338.html. As one Russian general put it, “the primary threats to Russian sovereignty” are “stemming from U.S.-funded social and political movements such as color revolutions, the Arab Spring, and the Maidan movement.”16Charles K. Bartles, “Getting Gerasimov Right,” Military Review volume 96, number 1 (2016): 37. It follows that Russia and China require a robust military deterrent and political strategy to push back and balance against this expression of American hegemony into their areas of core interest.17Dmitry Gorenburg, “Countering Color Revolutions: Russia’s New Security Strategy and Its Implications for U.S. Policy,” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo Number 342 (September 2014): 1–2, http://www.ponarseurasia.org/sites/default/files/policy-memos-pdf/Pepm342_Gorenburg_Sept2014.pdf.

Russia also views alliance expansion explicitly tied to democracy promotion as a threat to its regime security. For example, NATO expansion tied to democracy promotion made NATO not only a military alliance, but also a tool of democratic expansion. In this sense, Russia views continued talk of NATO expansion in terms of traditional security and in terms of how it affects the Russian regime’s security. As Russia scholar Andrei Tsygankov explains, a “more recent perception by the Kremlin betrays fear of the alliance as an offensive military organization employed to meet the larger objective to dismantle Russia’s political regime.”18Andrei P. Tsygankov, “The Sources of Russia’s Fear of NATO,” Communist and Post-Communist Studies volume 51, number 2 (2018): 102. Russia views further NATO expansion as a growing military club and a vehicle for democracy promotion with armed force behind it that threatens territory and the regime’s ability to maintain its rule.

In China, policymakers watch U.S. actions that they perceive as undermining the legitimacy of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in Hong Kong and supporting an independent Taiwan, among other actions, and conclude that this is in line with a grand strategy targeting the Chinese regime. Wang Jisi, president of the Institute of International and Strategic Studies at Peking University, explains China presumes “that the Americans intended to sow the seeds of dissent in China and eventually topple the CCP.”19Wang Jisi, “The Plot against China? How Beijing Sees the New Washington Consensus.” Foreign Affairs volume 100, number 4 (2021): 52. Similarly, Russia views American efforts at “democracy promotion as a cover for U.S.-sponsored regime change.”20Eugene Rumer and Richard Sokolsky, “Thirty Years of U.S. Policy Toward Russia: Can the Vicious Circle Be Broken?” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, June 20, 2019, https://carnegieendowment.org/2019/06/20/thirty-years-of-u.s.-policy-toward-russia-can-vicious-circle-be-broken-pub-79323. Or, Keir Giles, a Russia expert at Chatham House, says it, Russia assumes “the essential aim of western policy is to expand its space of influence or bring about regime change in Russia.”21Keir Giles, “What Deters Russia,” Chatham House, September 23, 2021, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2021/09/what-deters-russia, 67. To both, providing any support, material or otherwise, to protests against the regime is seen as the first step to potential U.S.-backed regime change.

Some American policymakers call China and Russia’s claims about fearing a U.S. regime change cynical, arguing that their statements are merely targeted toward domestic audiences.22Michael McFaul, “Putin Needed an American Enemy. He Picked Me.” Washington Post, May 11, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/posteverything/wp/2018/. While probably true at times, with regular statements in prominent outlets by current and former U.S. officials about a desire or interest in overthrowing regimes in Beijing and Moscow, among other countries—and given U.S. wars to oust leaders—these leaders take threats to their regime seriously.23Fred Kaplan, “Don’t Pick a Cold War You Can’t Win,” Slate, July 24, 2020, https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2020/07/pompeo-china-cold-war.html; Zack Cooper and Hal Brands, “America Will Only Win When China’s Regime Fails,” Foreign Policy, March 11, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/03/11/america-chinas-regime-fails/; As Fredrick Kagan writes, articulating a common Washington view, “We must cajole Russia into developing a new national identity not bound in the subjugation of a large empire and military might but rather as a peaceful democratic state.” Frederick W. Kagan, “Russia: The Kremlin’s Many Revisions,” Rise of the Revisionists: Russia, China, and Iran, ed. Gary J. Schmitt (Washington D.C.: American Enterprise Institute, 2018): 38; Anders Åslund and Leonid Gozman, “Russia After Putin: How to Rebuild the State,” Atlantic Council, February 24, 2021, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/russia-after-putin-report/.

Three issues made more difficult by regime change fears

China and Russia’s fears of American-led regime change have real-world implications for U.S. policy that are underexamined. Most notably, these fears encourage both Russia and China to take steps to obtain greater regime security against external threats from U.S. influence. This unfortunately is then used by some American policymakers as evidence that the regimes are nefarious and even greater democracy promotion is necessary, creating a spiral of worsening relations with China, Russia, and other nations.

This negatively affects U.S. interests in three specific areas: arms control; alliances; and, counterintuitively, human rights and democracy.

Arms Control

Viewing a nuclear deterrent as the ultimate defense for the regime, fears of regime change helped start a new missile-based arms race as both China and Russia seek to retain a robust nuclear deterrent to defend their regimes.24This is a contributing factor in the dismantling of the INF treaty. Austin Long, “Russian Nuclear Forces and Prospects for Arms Control,” RAND Corporation, Testimony Before the House Committee on Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Terrorism, Nonproliferation, and Trade, June 21, 2018, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/testimonies/CT400/CT495/RAND_CT495.pdf. The current U.S. nuclear posture that includes ballistic missile defense programs, coupled with the U.S. history of democracy promotion, looks particularly threatening to states with regime security concerns.25Michael T. Klare, “Why ‘Overmatch’ Is Overkill,” Nation, December 20, 2018, https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/overmatch-pentagon-military-budget-strategy/; Austin Long, “Nuclear Strategy in an Era of Great Power Competition,” Texas National Security Review, February 13, 2018, https://tnsr.org/roundtable/policy-roundtable-trump-administrations-nuclear-posture-review/#essay3; Charles K. Bartles, “Russian Threat Perception and the Ballistic Missile Defense System,” Journal of Slavic Military Studies volume 30, number 2 (2017): 152–169. Threatened nations may perceive that a robust deterrent has stopped the United States from attempting intervention on behalf of a domestic opposition movement so far—and continued American nuclear modernization is an attempt to remove this deterrent.

Fear of potential regime change backed by ballistic missile defense and global strike systems has driven doctrinal change in Russia. Moscow’s fear, as former U.S. Department of Defense analyst Thomas R. McCabe explains, is that “western technological superiority and the possibility that western technological surprise may render their defenses obsolete,” removing the deterrent that would guarantee regime security.26Thomas R. McCabe, “The Russian Perception of the NATO Aerospace Threat: Could It Lead to Preemption?” Air & Space Power Journal volume 30, number 3 (2016): 71. In particular, U.S. missile defense technology and missile modernization have caused, as a senior political scientist at the RAND Corporation explained in 2018, “Russian leadership to fear U.S.-sponsored unrest (as Russian leaders believe happened in Ukraine), backed up with precision munitions supplied by the United States and its allies. The Russians think they have seen this movie before in Serbia, Libya, Iraq, and, if not for timely Russian intervention, Syria.”27Austin Long, “Russian Nuclear Forces and Prospects for Arms Control.” As some Russian participants at a Track II nuclear dialogue put it a few years ago when discussing missile defense technology, “Russian complaints about strategic military problems are a verbalization of subliminal fears of a color revolution. And Putin wants a guarantee that no color revolution happens in Russia.”28Mikhail Tsypkin and Diana Wueger, “Twenty-First Century Strategic Stability, A U.S.-Russia Track II Dialogue,” Project on Advanced Systems and Concepts for Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction, U.S. Naval Postgraduate School, October 2014, https://calhoun.nps.edu/handle/10945/44734.

Similarly, as the Chinese admit, their nuclear forces are premised on providing the “strategic cornerstone for safeguarding national sovereignty.”29“China’s Military Strategy.” As emerged over many meetings with Chinese officials and academics, the Chinese view American intentions as “aimed at overthrowing the Chinese Communist Party. In this context, China’s leaders are highly motivated not to lose their ability to threaten to retaliate credibly.”30Brad Roberts, ed., “Taking Stock: U.S.-China Track 1.5 Nuclear Dialogue,” Center for Global Security Research, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, December 2020, https://cgsr.llnl.gov/content/assets/docs/CGSR_US-China-Paper.pdf, 27–28. The result is a concerted effort toward nuclear modernization, the pursuit of hypersonic missiles, and increased arsenal size.31Jeffrey W. Knopf, “Conventional Challenges to Strategic Stability: Chinese Perceptions of Hypersonic Technology and the Security Dilemma,” Regional Variations on Deterrence and Stability, Lawrence Rubin and Adam N. Stulberg, eds. (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2018): 281.

In general, this means that fears of regime insecurity directly harm arms control agreements and harm nuclear stability.

At the same time, U.S. policymakers focusing on internal characteristics in China and Russia as a basis for resisting arms control talks, and blaming the lack of arms control on their governing regimes, only encourages nuclear arms racing that harms U.S. goals.32Michael Pompeo and Marshall Billingslea, “Why China’s Nuclear Build-Up Should Worry the West,” U.S. Department of State, January 4, 2021, https://2017-2021.state.gov/why-chinas-nuclear-build-up-should-worry-the-west/index.html; Rebeccah L. Heinrichs, “The CCP’s Refusal to Join the U.S. in Arms Talks Intensifies Concerns about China’s Nukes,” Hudson Institute, July 8, 2020, https://www.hudson.org/research/16207-the-ccp-s-refusal-to-join-the-u-s-in-arms-talks-intensifies-concerns-about-china-s-nukes; Reuel Marc Gerecht, “The Iran Deal Is Strategically and Morally Absurd,” Atlantic, May 4, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/05/iran-nuclear-deal-flawed/559595/. Focusing on the internal characteristics of states as a feature of U.S. grand strategy limits the extent of global cooperation expected, reducing the range of options to advance arms control and nuclear moderation.

Alliances

China and Russia correctly see U.S. alliance expansion as tied to democracy promotion and view U.S. alliances as vehicles to expand American primacy.33Rajan Menon and William Ruger, “NATO Enlargement and US Grand Strategy: A Net Assessment,” International Politics volume 57, issue 3 (2020): 371–400. Reflecting this, China and Russia share an interest in challenging America’s alliances, with both trying to sow disunity among U.S. allies and find sympathetic partners to contest U.S. interests. Russian defense analysts, for example, have pinpointed NATO member states for Russia to target to prevent them from supporting regime change in Moscow.34Andrei P. Tsygankov, “The Sources of Russia’s Fear of NATO,” Communist and Post-Communist Studies volume 51, number 2 (June 2018): 101–11.; Dmitry Gorenburg, “Countering Color Revolutions”: 3. China has also attempted to promote its influence among U.S. allies, such as Australia and New Zealand, and to create regional partnerships in the Asia-Pacific that exclude the United States.35Rob Schmitz, “Australia and New Zealand Are Ground Zero for Chinese Influence,” NPR, October 2, 2018, https://www.npr.org/2018/10/02/627249909/australia-and-new-zealand-are-ground-zero-for-chinese-influence.

Problematically, this competition for influence then leads the United States to view its alliances and partnerships even more through the lens of democracy, rather than focus on U.S. strategic interests. When tying alliance decisions to democracy, it encourages the United States to include a greater number of alliance partners than it otherwise would think to do on a purely military basis, or to treat democratic states in security danger as near allies. For instance, in recent months, the Biden administration discussed Taiwan and Ukraine as vital U.S. strategic partners not due to their military importance but in terms of defending democracy.36“Joint Statement on the U.S.-Ukraine Strategic Partnership,” The White House, September 1, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/09/01/joint-statement-on-the-u-s-ukraine-strategic-partnership/; Derek Grossman, “Biden Administration Shows Unwavering Support for Taiwan,” RAND Corporation, October 20, 2021, https://www.rand.org/blog/2021/10/biden-administration-shows-unwavering-support-for-taiwan.html. Adding Ukraine to NATO does not make sense to promote greater U.S. security. But when the emphasis becomes one of defending Ukrainian democracy or expanding the democratic community, the prospect of adding Ukraine becomes more tantalizing.37Michael McFaul, “The U.S. and Ukraine Need to Reboot Their Relationship. Here’s How They Can Do It.” Washington Post, August 23, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2021/08/23/us-ukraine-need-reboot-their-relationship-heres-how-they-can-do-it/; William B. Taylor, “The Biden Doctrine Should Start with Ukraine,” United States Institute of Peace, September 10, 2021, https://www.usip.org/publications/2021/09/biden-doctrine-should-start-ukraine. Similarly, recent debates about making a clearer commitment to defend Taiwan have emphasized the importance of defending Taiwanese democracy.38Roger F. Wicker, “Joe Biden Should Come Out and Say It: America Will Help Defend Taiwan,” Wall Street Journal, November 19, 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/joe-biden-should-come-out-and-say-it-america-will-help-defend-taiwan-china-military-xi-11637357925; Josh Rogin, “The Battle to Protect Taiwan’s Democracy Is Already Underway,” Washington Post, November 18, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2021/11/18/battle-protect-taiwans-democracy-is-already-underway/; Lee Edwards, “U.S. Must Defend Taiwan’s Independence,” Heritage Foundation, October 21, 2021, https://www.heritage.org/asia/commentary/us-must-defend-taiwans-independence.

Chinese and Russian actions against each then become even greater impetuses for the United States to link alliance expansion to democracy promotion without regard for the escalatory signals it sends. Making democracy the basis of alliance decision-making then makes every pro-democracy movement appear as fundamentally aligned with the United States and a threat to China and Russia. This encourages greater Russian and Chinese interference in democracy movements outside their borders due to democracy.39Ivana Stradner and Milan Jovanović, “Montenegro Is the Latest Domino to Fall Toward Russia,” Foreign Policy, September 17, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/09/17/montenegro-latest-domino-fall-russia-pro-west-europe-nato/. Repressing democracy movements then, unfortunately, leads to calls for western alliances to support these activists, further confirming the fears of both Russia and China as to what lurks behind these movements.

The U.S. focus on democracy and the fears of regime change it stokes also push China and Russia closer together.40Alexander Gabuev, “Why Russia and China Are Strengthening Security Ties,” Foreign Affairs, September 24, 2018, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2018-09-24/why-russia-and-china-are-strengthening-security-ties. In recent months, this has manifested through increased discussions about how both countries should work together more, directly referencing President Biden’s renewed interest in democracy as something to defend against.41Xu Keyue and Liu Xin, “China, Russia Defy American-Style Democracy before U.S. Summit,” Global Times, November 18, 2021, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202111/1239368.shtml. As Chinese defense minister Wang Yi explained in March, “The Biden administration regards China and Russia as rivals and enemies, and advances human rights and democracy in his policy. Therefore, he may…challenge the existing non-democratic systems and promote the change of democratic regimes.”42Amber Wang, “China and Russia Should Work Together to Combat ‘Colour Revolutions’, Says Chinese Foreign Minister,” South China Morning Post, March 8, 2021, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3124567/china-and-russia-should-work-together-combat-colour. Both China and Russia believe U.S.-supported democracy forces harm their internal regime security and have started to work together in different venues to push back against American interests.43Paul Stronski and Nicole Ng, “Cooperation and Competition: Russia and China in Central Asia, the Russian Far East, and the Arctic,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, February 28, 2018, https://carnegieendowment.org/2018/02/28/cooperation-and-competition-russia-and-china-in-central-asia-russian-far-east-and-arctic-pub-75673; Robert Sutter, “When Will Closer China-Russia Cooperation Impact U.S. Policy Debate?” Diplomat, September 14, 2018, https://thediplomat.com/2018/09/when-will-closer-china-russia-cooperation-impact-us-policy-debate/; Liu Fenghua, “China-Russia Comprehensive Strategic Partnership: Formation, Features, and Prospects,” China International Studies Volume 59 (2016): 61–75. Today’s cooperation thus has a clear goal: to challenge U.S. democracy promotion that threatens their regimes.

Civil society and moral hazards

A grand strategy emphasizing democracy promotion creates a final paradox where actions taken that, in principle, are supposed to aid civil society organizations (CSOs), democracy activists, and promote local democracy can end up harming them. The states most concerned about maintaining regime security are least likely to permit external support for activists and civil society organizations. They will take direct actions to prevent external influence, targeting those they think will work to reduce their regime’s power.44Roman Goncharenko, “NGOs in Russia: Battered, but Unbowed,” Deutsche Welle, November 21, 2017, https://www.dw.com/en/ngos-in-russia-battered-but-unbowed/a-41459467.

When democracy promotion is made a central pillar of U.S. foreign policy, activists can become regarded as proxies for pro-U.S. regime change policies, ultimately harming CSOs working in these countries.45Davin O’Regan, “Ending Forever Wars but Not Interventionism: Rethinking U.S. Civil Society Assistance Policy,” War on the Rocks, June 30, 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/06/ending-forever-wars-but-not-interventionism-rethinking-u-s-civil-society-assistance-policy/. Regimes then crack down on NGOs, repress civil society, and restrict popular protests, which U.S. policymakers see as clear evidence of regime nefariousness to which the United States must then respond, furthering the spiral.46Dave Elseroad, “America Must Lead the International Response to Russia’s Human Rights Crisis,” Atlantic Council, September 16, 2021, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/america-must-lead-the-international-response-to-russias-human-rights-crisis/; Elizabeth Warren, “It Is Time for the United States to Stand Up to China in Hong Kong,” Foreign Policy, October 3, 2019, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/10/03/it-is-time-for-the-united-states-to-stand-up-to-china-in-hong-kong/.

One example of this playing out was how Chinese leaders saw recent protests in Hong Kong against China’s national security law as tied to U.S. interests after passage of U.S. laws designed to support the protestors.47Susan V. Lawrence and Michael F. Martin, “China’s National Security Law for Hong Kong: Issues for Congress R46473,” Congressional Research Service, updated August 3, 2020, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46473. Chinese officials and diplomats harshly commented on U.S. support for the dissidents and labeled many of the protestors as backed by U.S. intelligence agencies, leading to more crackdowns and repression.48Barbara Lippert and Volker Perthes, eds., “Strategic Rivalry between United States and China,” Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, April 6, 2020, https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/publication/strategic-rivalry-between-united-states-and-china/; Teddy Ng, “China Hits Out at United States for ‘Stirring Up Colour Revolutions and Chaos’ to ‘Under Banner of Human Rights’ in Apparent Reference to Xinijang Camps and Hong Kong Protests,” South China Morning Post, December 11, 2019, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3041677/regime-change-chaos-merchants-china-lashes-out-united-states. Similar actions played out in Russia following the 2011 election protests.49Kathy Lally and Karen DeYoung, “Putin Accuses Clinton, U.S. of Fomenting Election Protests,” Washington Post, December 8, 2011, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/putin-accuses-clinton-us-of-stirring-election-protests/2011/12/08/gIQA0MUDfO_story.html. Civil society actors, by being tied to U.S. democracy promotion efforts, often end up harmed by these actions. It is ultimately a net negative for democracy globally to associate democracy with continued U.S. primacy in the international system.

Ultimately, distrust and fear of foreign interference and support for various CSOs should not come as a surprise. The United States itself is resistant to interference in its domestic affairs, as the 2016 election and subsequent actions demonstrated. President Biden specifically campaigned against foreign interference and lobbying in the United States as it was viewed as improper and at times a security threat.50As his campaign stated it: “There is no reason why a foreign government should be permitted to lobby Congress or the Executive Branch, let alone interfere in our elections. If a foreign government wants to share its views with the United States or to influence its decision-making, it should do so through regular diplomatic channels.” See “The Biden Plan to Guarantee Government Works for the People,” Biden Harris Democrats, accessed December 7, 2021, https://joebiden.com/governmentreform/. China and Russia view a U.S. fixation on democracy promotion in similar terms.

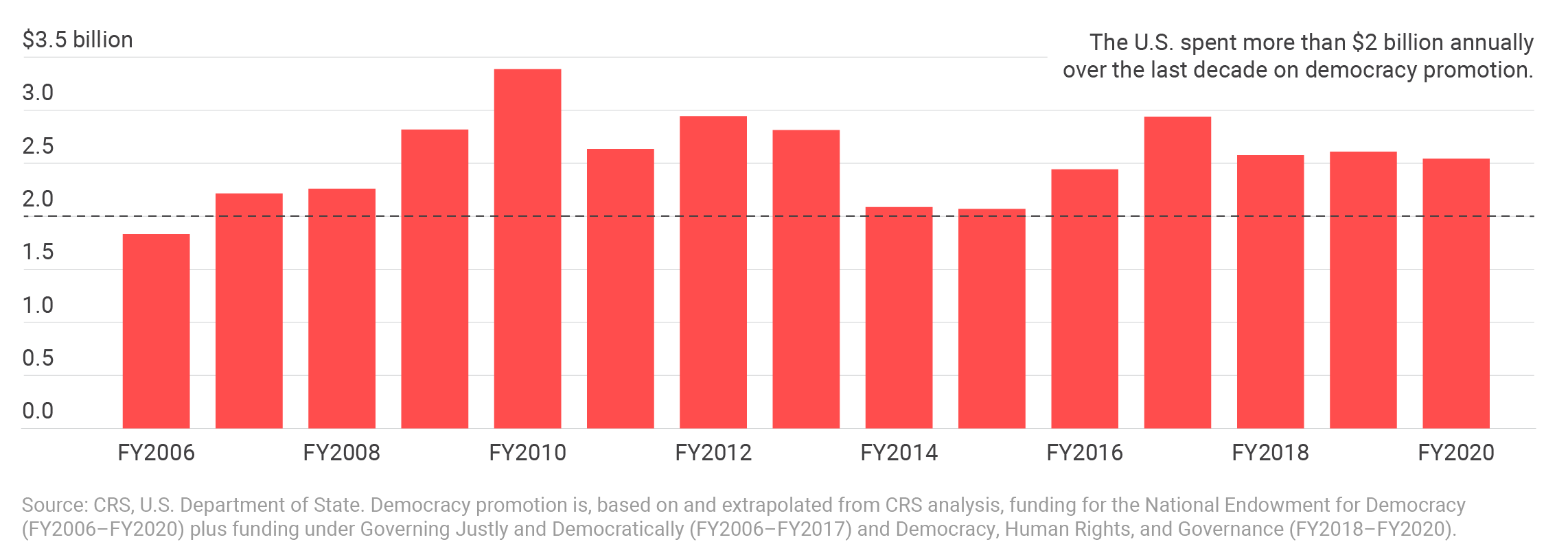

Annual U.S. funding for democracy promotion

Most of U.S. democracy promotion assistance, as categorized by the Congressional Research Service, goes through USAID, the State Department, and the National Endowment for Democracy. In practice, however, other U.S. spending in other budget categories also promotes democracy abroad.

U.S. efforts to promote democracy, other than by modeling democracy at home, can lead to a moral hazard where democracy activists and protestors take to the streets against certain regimes expecting U.S. support or even directly asking for it.51David Ignatius, “The U.S. Has to Tread in the Middle When Handling the Hong Kong Protests,” Washington Post, August 15, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/global-opinions/the-us-has-to-tread-in-the-middle-when-handling-the-hong-kong-protests/2019/08/15/ee89b7b0-bf88-11e9-a5c6-1e74f7ec4a93_story.html. This creates both an expectation of American support from the activists and a view among China, Russia, and others that an American hand is behind certain protests when it is not. This makes it easier politically for Beijing and Moscow to mobilize for repression. It also makes it difficult for activists and regimes to accept agreements and de-escalate when the specter of potential U.S. intervention looms. Rather than producing off-ramps to avoid worsening relations, this moral hazard amplifies regime security concerns.

The larger problem with prioritizing democracy promotion in U.S. foreign policy is it can encourage foolish wars on behalf of democratic, or seemingly democratic, opposition groups, as in Libya and Syria. Some analysts have gone so far as to argue for a “right to assist” doctrine that would encourage greater assistance to local activists abroad and use U.S. force and economic might to defend their ability to mobilize against current regimes whenever they see fit.52Patrick W. Quirk, “Biden’s Summit for Democracy Must Be More than Aspirational,” National Interest, November 6, 2021, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/biden%E2%80%99s-summit-democracy-must-be-more-aspirational-195827. This is a dangerous logic that, similar to the “responsibility to protect” doctrine, would create compulsions to intervene abroad recklessly, while stoking the regime security fears of Russia and China.

Breaking the regime change cycle after the Summit for Democracy

The Biden administration’s Summit for Democracy has created diplomatic headaches, with various participants arguing over who should and should not be invited.53Humeyra Pamuk and Simon Lewis, “Biden’s Democracy Summit: Problematic Invite List Casts Shadow on Impact,” Reuters, November 7, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/bidens-democracy-summit-problematic-invite-list-casts-shadow-impact-2021-11-07/; Steven Feldstein, “Who’s In and Who’s Out From Biden’s Democracy Summit,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, November 22, 2021, https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/11/22/who-s-in-and-who-s-out-from-biden-s-democracy-summit-pub-85822; Nahal Toosi, “Are You on the List? Biden’s Democracy Summit Spurs Anxieties—and Skepticism,” Politico, November 11, 2020, https://www.politico.com/news/2020/11/28/biden-democracy-summit-440819; Amy Mackinnon, “Biden’s Summit for Democracy Will Include Some Not-So-Democratic Countries,” Foreign Policy, October 19, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/10/19/biden-summit-for-democracy-poland-mexico-philippines/. While these headaches are real, they are manageable compared to those worsened by maintaining democracy promotion as the focus of U.S. grand strategy. Any good from democracy promotion will likely get overcome by the downside: making competition with China and Russia more ideological and less focused on making prudent choices that advance vital U.S. security and prosperity interests.

An overemphasis on democracy promotion has already transformed the crises in Taiwan and Ukraine into more ideological contests, rather than discussions about core national interests and foreign policy priorities. By hosting the summit, tensions will likely escalate, as more global issues get cast in terms of democracy against autocracy. The United States should take greater steps to consider regime security concerns more seriously and break the connection between democracy promotion and U.S. grand strategy.

Overall, moving away from a grand strategy that focuses on making the world safe for democracy will be a change from the past few decades, but is essential for creating prudent foreign policy fit for today’s geostrategic reality. Past U.S. policies make it challenging to credibly show the United States is not interested in regime change. But the difficulty in reversing regime security fears does not mean the United States should actively inflame these fears further.

In the near term, the United States should pursue prudent policies toward Taiwan and Ukraine. Reframing the crises in Ukraine and Taiwan, not as challenges to global democracy, but instead as territorial conflicts of asymmetric importance, is a good first step. Generally, U.S. leaders making sober assessments about U.S. interests and not calling every crisis an existential defense of democracy is necessary to de-escalate regime security fears.

In the longer term, more extensive discussions should occur about the multi-decade path of infusing democracy promotion into U.S. grand strategy and all the drawbacks that have resulted. Resisting intervention when faced with adversarial regimes and working to find common ground with non-democratic governments will go a long way toward reducing acute fears and allowing greater cooperation on areas of mutual interest. Focusing on external features of states as a basis of U.S. foreign policy is the best way forward. Increased focus on democracy will increase tensions with China and Russia, heighten their regime security concerns, make critical areas of cooperation unavailable, and make conflict more likely. Rather than a democratic peace, democracy promotion is more likely to make competition hotter as regime protection becomes a priority.

The United States should not give up supporting liberal democracy abroad. However, it should be far more cautious about how exactly it does so, given the dangers U.S. statements and actions create for local democratic activists. And while it is hard to decide where exactly to draw that line, it is easy enough to remember that supporting democracy begins at home. Modeling as a beacon of democracy at home rather than abroad is an old idea worth renewed attention, one that has proven effective in truly promoting liberal democracy before.

Endnotes

- 1“The Summit for Democracy,” U.S. Department of State, accessed December 7, 2021, https://www.state.gov/summit-for-democracy/.

- 2Tony Smith, “Making the World Safe for Democracy in the American Century,” Diplomatic History volume 23, number 2 (1999): 173–188.

- 3Joseph R. Biden Jr., “Why American Must Lead Again: Recusing U.S. Foreign Policy after Trump.” Foreign Affairs, March/April 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-01-23/why-america-must-lead-again.

- 4Tony Smith, America’s Mission: The United States and the Worldwide Struggle for Democracy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995); Michael C. Desch, “America’s Liberal Illiberalism: The Ideological Origins of Overreaction in U.S. Foreign Policy,” International Security 32, no. 3 (2007): 7–43.

- 5Madeleine K. Albright, “The Coming Democratic Revival,” Foreign Affairs, November/December 2021, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/world/2021-10-19/madeleine-albright-coming-democratic-revival; Nahal Toosi, “An ‘Illustrative Menu of Options,’” Politico, November 4, 2021, https://www.politico.com/news/2021/11/04/biden-democracy-summit-technology-519530; Richard Fontaine and Jared Cohen, “Biden’s Democracy Summit Needs to Produce More Than a Bland Statement,” Foreign Policy, November 12, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/11/12/biden-democracy-summit-china-russia-authoritarianism/; Anne Applebaum, “The Bad Guys Are Winning,” Atlantic, November 15, 2021, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2021/12/the-autocrats-are-winning/620526/.

- 6Anatoly Antonov and Qin Gang, “Russian and Chinese Ambassadors: Respecting People’s Democratic Rights,” National Interest, November 26, 2021, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/russian-chinese-ambassadors-respecting-people%E2%80%99s-democratic-rights-197165.

- 7Lindsey A. O’Rourke, Covert Regime Change: America’s Secret Cold War (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2018); Dov H. Levin, Meddling in the Ballot Box: The Causes and Effects of Partisan Electoral Interventions (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020); John M. Owen, “The Foreign Imposition of Domestic Institutions,” International Organization 56, no. 2 (2002): 375–409.

- 8Benjamin Denison, “The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same: The Failure of Regime‐Change Operations,” Cato Institute, January 6, 2020, https://www.cato.org/policy-analysis/more-things-change-more-they-stay-same-failure-regime-change-operations.

- 9Barry Posen defines “grand strategy” as “a political-military means-ends chain, a state’s theory about how it can best ‘cause’ security for itself.” See Barry R. Posen, The Sources of Military Doctrine: France, Britain, and Germany Between the World Wars (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1984): 13; “ William J. Clinton, A National Security Strategy of Engagement and Enlargement (Washington: White House, 1994), http://nssarchive.us/NSSR/1994.pdf; George W. Bush, The National Security Strategy of the United States of America (Washington: White House, 2002), http://nssarchive.us/NSSR/2002.pdf; Barack Obama, National Security Strategy of the United States of America (Washington: White House, 2010), http://nssarchive.us/NSSR/2010.pdf.

- 10William J. Clinton, A National Security Strategy of Engagement and Enlargement.

- 11Seva Gunitsky, Aftershocks (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017): 198–230.

- 12“Transcript: Mike Pompeo talks with Michael Morell on “Intelligence Matters,” CBS News, May 1, 2019, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/transcript-mike-pompeo-talks-with-michael-morell-on-intelligence-matters/; Elliott Abrams, “A New Path to Venezuelan Democracy, Wall Street Journal, March 31, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/a-new-path-to-venezuelan-democracy-11585645210; Kate O’Keeffe and William Mauldin, “Mike Pompeo Urges Chinese People to Change Communist Party,” Wall Street Journal, July 23, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/secretary-of-state-pompeo-to-urge-chinese-people-to-change-the-communist-party-11595517729; “Trump Should Insist on Libya-Style Denuclearization for North Korea: Bolton,” Reuters, March 23, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-trump-bolton-northkorea/trump-should-insist-on-libya-style-denuclearization-for-north-korea-bolton-idUSKBN1GZ37A.

- 13In Russian official discourse, there is an assumption that the United States was largely behind the “Color Revolutions” in their near abroad. See Jeanne L. Wilson, “The Legacy of the Color Revolutions for Russian Politics and Foreign Policy,” Problems of Post-Communism volume 57, issue 2 (2010): 21–36; Yulia Nikitinа, “The ‘Color Revolutions’ and ‘Arab Spring’ in Russian Official Discourse,” Connections volume 14, number 1 (2014): 87–104; Kimberly Marten, “Putin’s Choices: Explaining Russian Foreign Policy and Intervention in Ukraine,” Washington Quarterly volume 38, number 2 (April 2015): 189–204. Similarly, Chinese discourse has also framed color revolutions abroad as driven by the United States to uphold their strategic interests. See Andrew J. Nathan and Andrew Scobell, “How China Sees America: The Sum of Beijing,” Foreign Affairs Volume 91, number 1 (2012): 32–47; Karrie J. Koesel and Valerie J. Bunce, “Diffusion-Proofing: Russian and Chinese Responses to Waves of Popular Mobilizations against Authoritarian Rulers,” Perspectives on Politics volume 11, number 3 (September 2013): 753–68; Titus C. Chen, “China’s Reaction to the Color Revolutions: Adaptive Authoritarianism in Full Swing,” Asian Perspective volume 34, number 2 (2010): 5–51.

- 14“China’s Military Strategy,” Ministry of National Defense of the People’s Republic of China, May 26, 2015, http://eng.mod.gov.cn/Press/2015-05/26/content_4586805.htm.

- 15Stephanie Pezard and Ashley L. Rhoades, “What Provokes Putin’s Russia?” RAND Corporation, January 2020, https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PE338.html.

- 16Charles K. Bartles, “Getting Gerasimov Right,” Military Review volume 96, number 1 (2016): 37.

- 17Dmitry Gorenburg, “Countering Color Revolutions: Russia’s New Security Strategy and Its Implications for U.S. Policy,” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo Number 342 (September 2014): 1–2, http://www.ponarseurasia.org/sites/default/files/policy-memos-pdf/Pepm342_Gorenburg_Sept2014.pdf.

- 18Andrei P. Tsygankov, “The Sources of Russia’s Fear of NATO,” Communist and Post-Communist Studies volume 51, number 2 (2018): 102.

- 19Wang Jisi, “The Plot against China? How Beijing Sees the New Washington Consensus.” Foreign Affairs volume 100, number 4 (2021): 52.

- 20Eugene Rumer and Richard Sokolsky, “Thirty Years of U.S. Policy Toward Russia: Can the Vicious Circle Be Broken?” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, June 20, 2019, https://carnegieendowment.org/2019/06/20/thirty-years-of-u.s.-policy-toward-russia-can-vicious-circle-be-broken-pub-79323.

- 21Keir Giles, “What Deters Russia,” Chatham House, September 23, 2021, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2021/09/what-deters-russia, 67.

- 22Michael McFaul, “Putin Needed an American Enemy. He Picked Me.” Washington Post, May 11, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/posteverything/wp/2018/.

- 23Fred Kaplan, “Don’t Pick a Cold War You Can’t Win,” Slate, July 24, 2020, https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2020/07/pompeo-china-cold-war.html; Zack Cooper and Hal Brands, “America Will Only Win When China’s Regime Fails,” Foreign Policy, March 11, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/03/11/america-chinas-regime-fails/; As Fredrick Kagan writes, articulating a common Washington view, “We must cajole Russia into developing a new national identity not bound in the subjugation of a large empire and military might but rather as a peaceful democratic state.” Frederick W. Kagan, “Russia: The Kremlin’s Many Revisions,” Rise of the Revisionists: Russia, China, and Iran, ed. Gary J. Schmitt (Washington D.C.: American Enterprise Institute, 2018): 38; Anders Åslund and Leonid Gozman, “Russia After Putin: How to Rebuild the State,” Atlantic Council, February 24, 2021, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/russia-after-putin-report/.

- 24This is a contributing factor in the dismantling of the INF treaty. Austin Long, “Russian Nuclear Forces and Prospects for Arms Control,” RAND Corporation, Testimony Before the House Committee on Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Terrorism, Nonproliferation, and Trade, June 21, 2018, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/testimonies/CT400/CT495/RAND_CT495.pdf.

- 25Michael T. Klare, “Why ‘Overmatch’ Is Overkill,” Nation, December 20, 2018, https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/overmatch-pentagon-military-budget-strategy/; Austin Long, “Nuclear Strategy in an Era of Great Power Competition,” Texas National Security Review, February 13, 2018, https://tnsr.org/roundtable/policy-roundtable-trump-administrations-nuclear-posture-review/#essay3; Charles K. Bartles, “Russian Threat Perception and the Ballistic Missile Defense System,” Journal of Slavic Military Studies volume 30, number 2 (2017): 152–169.

- 26Thomas R. McCabe, “The Russian Perception of the NATO Aerospace Threat: Could It Lead to Preemption?” Air & Space Power Journal volume 30, number 3 (2016): 71.

- 27Austin Long, “Russian Nuclear Forces and Prospects for Arms Control.”

- 28Mikhail Tsypkin and Diana Wueger, “Twenty-First Century Strategic Stability, A U.S.-Russia Track II Dialogue,” Project on Advanced Systems and Concepts for Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction, U.S. Naval Postgraduate School, October 2014, https://calhoun.nps.edu/handle/10945/44734.

- 29“China’s Military Strategy.”

- 30Brad Roberts, ed., “Taking Stock: U.S.-China Track 1.5 Nuclear Dialogue,” Center for Global Security Research, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, December 2020, https://cgsr.llnl.gov/content/assets/docs/CGSR_US-China-Paper.pdf, 27–28.

- 31Jeffrey W. Knopf, “Conventional Challenges to Strategic Stability: Chinese Perceptions of Hypersonic Technology and the Security Dilemma,” Regional Variations on Deterrence and Stability, Lawrence Rubin and Adam N. Stulberg, eds. (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2018): 281.

- 32Michael Pompeo and Marshall Billingslea, “Why China’s Nuclear Build-Up Should Worry the West,” U.S. Department of State, January 4, 2021, https://2017-2021.state.gov/why-chinas-nuclear-build-up-should-worry-the-west/index.html; Rebeccah L. Heinrichs, “The CCP’s Refusal to Join the U.S. in Arms Talks Intensifies Concerns about China’s Nukes,” Hudson Institute, July 8, 2020, https://www.hudson.org/research/16207-the-ccp-s-refusal-to-join-the-u-s-in-arms-talks-intensifies-concerns-about-china-s-nukes; Reuel Marc Gerecht, “The Iran Deal Is Strategically and Morally Absurd,” Atlantic, May 4, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/05/iran-nuclear-deal-flawed/559595/.

- 33Rajan Menon and William Ruger, “NATO Enlargement and US Grand Strategy: A Net Assessment,” International Politics volume 57, issue 3 (2020): 371–400.

- 34Andrei P. Tsygankov, “The Sources of Russia’s Fear of NATO,” Communist and Post-Communist Studies volume 51, number 2 (June 2018): 101–11.; Dmitry Gorenburg, “Countering Color Revolutions”: 3.

- 35Rob Schmitz, “Australia and New Zealand Are Ground Zero for Chinese Influence,” NPR, October 2, 2018, https://www.npr.org/2018/10/02/627249909/australia-and-new-zealand-are-ground-zero-for-chinese-influence.

- 36“Joint Statement on the U.S.-Ukraine Strategic Partnership,” The White House, September 1, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/09/01/joint-statement-on-the-u-s-ukraine-strategic-partnership/; Derek Grossman, “Biden Administration Shows Unwavering Support for Taiwan,” RAND Corporation, October 20, 2021, https://www.rand.org/blog/2021/10/biden-administration-shows-unwavering-support-for-taiwan.html.

- 37Michael McFaul, “The U.S. and Ukraine Need to Reboot Their Relationship. Here’s How They Can Do It.” Washington Post, August 23, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2021/08/23/us-ukraine-need-reboot-their-relationship-heres-how-they-can-do-it/; William B. Taylor, “The Biden Doctrine Should Start with Ukraine,” United States Institute of Peace, September 10, 2021, https://www.usip.org/publications/2021/09/biden-doctrine-should-start-ukraine.

- 38Roger F. Wicker, “Joe Biden Should Come Out and Say It: America Will Help Defend Taiwan,” Wall Street Journal, November 19, 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/joe-biden-should-come-out-and-say-it-america-will-help-defend-taiwan-china-military-xi-11637357925; Josh Rogin, “The Battle to Protect Taiwan’s Democracy Is Already Underway,” Washington Post, November 18, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2021/11/18/battle-protect-taiwans-democracy-is-already-underway/; Lee Edwards, “U.S. Must Defend Taiwan’s Independence,” Heritage Foundation, October 21, 2021, https://www.heritage.org/asia/commentary/us-must-defend-taiwans-independence.

- 39Ivana Stradner and Milan Jovanović, “Montenegro Is the Latest Domino to Fall Toward Russia,” Foreign Policy, September 17, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/09/17/montenegro-latest-domino-fall-russia-pro-west-europe-nato/.

- 40Alexander Gabuev, “Why Russia and China Are Strengthening Security Ties,” Foreign Affairs, September 24, 2018, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2018-09-24/why-russia-and-china-are-strengthening-security-ties.

- 41Xu Keyue and Liu Xin, “China, Russia Defy American-Style Democracy before U.S. Summit,” Global Times, November 18, 2021, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202111/1239368.shtml.

- 42Amber Wang, “China and Russia Should Work Together to Combat ‘Colour Revolutions’, Says Chinese Foreign Minister,” South China Morning Post, March 8, 2021, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3124567/china-and-russia-should-work-together-combat-colour.

- 43Paul Stronski and Nicole Ng, “Cooperation and Competition: Russia and China in Central Asia, the Russian Far East, and the Arctic,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, February 28, 2018, https://carnegieendowment.org/2018/02/28/cooperation-and-competition-russia-and-china-in-central-asia-russian-far-east-and-arctic-pub-75673; Robert Sutter, “When Will Closer China-Russia Cooperation Impact U.S. Policy Debate?” Diplomat, September 14, 2018, https://thediplomat.com/2018/09/when-will-closer-china-russia-cooperation-impact-us-policy-debate/; Liu Fenghua, “China-Russia Comprehensive Strategic Partnership: Formation, Features, and Prospects,” China International Studies Volume 59 (2016): 61–75.

- 44Roman Goncharenko, “NGOs in Russia: Battered, but Unbowed,” Deutsche Welle, November 21, 2017, https://www.dw.com/en/ngos-in-russia-battered-but-unbowed/a-41459467.

- 45Davin O’Regan, “Ending Forever Wars but Not Interventionism: Rethinking U.S. Civil Society Assistance Policy,” War on the Rocks, June 30, 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/06/ending-forever-wars-but-not-interventionism-rethinking-u-s-civil-society-assistance-policy/.

- 46Dave Elseroad, “America Must Lead the International Response to Russia’s Human Rights Crisis,” Atlantic Council, September 16, 2021, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/america-must-lead-the-international-response-to-russias-human-rights-crisis/; Elizabeth Warren, “It Is Time for the United States to Stand Up to China in Hong Kong,” Foreign Policy, October 3, 2019, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/10/03/it-is-time-for-the-united-states-to-stand-up-to-china-in-hong-kong/.

- 47Susan V. Lawrence and Michael F. Martin, “China’s National Security Law for Hong Kong: Issues for Congress R46473,” Congressional Research Service, updated August 3, 2020, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46473.

- 48Barbara Lippert and Volker Perthes, eds., “Strategic Rivalry between United States and China,” Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, April 6, 2020, https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/publication/strategic-rivalry-between-united-states-and-china/; Teddy Ng, “China Hits Out at United States for ‘Stirring Up Colour Revolutions and Chaos’ to ‘Under Banner of Human Rights’ in Apparent Reference to Xinijang Camps and Hong Kong Protests,” South China Morning Post, December 11, 2019, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3041677/regime-change-chaos-merchants-china-lashes-out-united-states.

- 49Kathy Lally and Karen DeYoung, “Putin Accuses Clinton, U.S. of Fomenting Election Protests,” Washington Post, December 8, 2011, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/putin-accuses-clinton-us-of-stirring-election-protests/2011/12/08/gIQA0MUDfO_story.html.

- 50As his campaign stated it: “There is no reason why a foreign government should be permitted to lobby Congress or the Executive Branch, let alone interfere in our elections. If a foreign government wants to share its views with the United States or to influence its decision-making, it should do so through regular diplomatic channels.” See “The Biden Plan to Guarantee Government Works for the People,” Biden Harris Democrats, accessed December 7, 2021, https://joebiden.com/governmentreform/.

- 51David Ignatius, “The U.S. Has to Tread in the Middle When Handling the Hong Kong Protests,” Washington Post, August 15, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/global-opinions/the-us-has-to-tread-in-the-middle-when-handling-the-hong-kong-protests/2019/08/15/ee89b7b0-bf88-11e9-a5c6-1e74f7ec4a93_story.html.

- 52Patrick W. Quirk, “Biden’s Summit for Democracy Must Be More than Aspirational,” National Interest, November 6, 2021, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/biden%E2%80%99s-summit-democracy-must-be-more-aspirational-195827.

- 53Humeyra Pamuk and Simon Lewis, “Biden’s Democracy Summit: Problematic Invite List Casts Shadow on Impact,” Reuters, November 7, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/bidens-democracy-summit-problematic-invite-list-casts-shadow-impact-2021-11-07/; Steven Feldstein, “Who’s In and Who’s Out From Biden’s Democracy Summit,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, November 22, 2021, https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/11/22/who-s-in-and-who-s-out-from-biden-s-democracy-summit-pub-85822; Nahal Toosi, “Are You on the List? Biden’s Democracy Summit Spurs Anxieties—and Skepticism,” Politico, November 11, 2020, https://www.politico.com/news/2020/11/28/biden-democracy-summit-440819; Amy Mackinnon, “Biden’s Summit for Democracy Will Include Some Not-So-Democratic Countries,” Foreign Policy, October 19, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/10/19/biden-summit-for-democracy-poland-mexico-philippines/.

More on Asia

Featuring Lyle Goldstein

December 9, 2025

Events on Grand strategy