August 30, 2019

Exiting Afghanistan

Ending America's longest war

Key points

- The war in Afghanistan—now America’s longest at nearly 18 years—quickly achieved its initial aims: (1) to destroy the Al-Qaeda terrorist organization and (2) to punish the Taliban government that gave it haven. However, Washington extended the mission to a long and futile effort of building up the Afghan state to defeat the subsequent Taliban insurgency.

- The second phase of the war, the ongoing nation-building effort, has been a costly failure. It is irresponsible and counterproductive to pour more money and lives into this mission.

- The Afghan state’s success is desirable but unnecessary to U.S. security, and it is not worth the costs of continued war. Effective counterterrorism in Afghanistan does not require both successful state-building and counterinsurgency. The claim that it does burdens an achievable aim with one that is impossible at a reasonable cost.

- Despite the counterinsurgency failure, counterterrorism has succeeded in Afghanistan, even in areas where the Taliban exercise control. This is due to the U.S. military’s improved ability to remotely find and strike individual terrorists, increased U.S. will to militarily target terrorist organizations, and diminished Taliban willingness to host terrorists who target the United States.

- Counterterrorism will continue to succeed in Afghanistan when U.S. combat forces withdraw, leaving only the minimum necessary for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance missions, regardless of the success of state-building efforts or talks with the Taliban.

- U.S. withdrawal should not wait on the conclusion of talks with the Taliban or on Taliban talks with Afghanistan’s government.

Overview

It is long past time for the United States to exit the war in Afghanistan. The war is a wound bleeding away U.S. security and prosperity without benefit. Ideally, a rapid U.S. exit would happen alongside a deal with the Taliban but should not depend on it.

Afghanistan’s success as a state is desirable but not a security necessity for Americans. Nation-building does not justify keeping U.S. forces at war and spending $30 or $40 billion annually in Afghanistan. Military power is incapable of achieving that goal, at least not at an acceptable price. The United States does not need to perpetually occupy Afghanistan and conduct a counterinsurgency campaign to achieve its core security goal in Afghanistan—preventing terrorists there from targeting Americans. Counterterrorism does not require counterinsurgency.

The U.S. war in Afghanistan succeeded before it expanded into a failed nation-building effort. The United States invaded Afghanistan in 2001 (1) to destroy the Al-Qaeda terrorist organization and (2) to punish the Taliban government that gave it haven.1These goals are evident in the 2001 Authorization of Military Force legislation. Authorization for the Use of Military Force, Public Law 107-40, U.S. Statutes at Large 115 (2001): 224, https://www.congress.gov/107/plaws/publ40/PLAW-107publ40.pdf Within a year, the Taliban had fallen and its leadership dispersed. U.S. strikes and local allies had destroyed much of Al-Qaeda’s core, and the remainder was hidden and hunted. U.S. leverage to negotiate a withdrawal agreement was at its zenith. The United States should then have brought most of the troops home but for a small presence to hunt Al-Qaeda survivors and train Afghan security forces. That residual force could have been withdrawn somewhat later, once Al-Qaeda was rendered ineffective as a trans-national terrorist organization.

Instead, U.S. foreign policymakers confused the effectiveness of Afghanistan’s government with counterterrorism. They erroneously decided counterterrorism required counterinsurgency—that denying haven to Al-Qaeda required making the central government a success that could permanently suppress insurgency.

That misconception burdened an achievable aim with an impossible one: to transform a notoriously fractured and weak state into a strong and modern one. A host of secondary goals followed: training a professional Afghan military and national police force, suppressing corruption, ending heroin production, establishing women’s rights, aiding the development of modern infrastructure, and more. These goals served laudable intentions but were unconnected to U.S. security. Because they are only possible as outcomes of successful nation building, these goals are also impossible to achieve quickly.

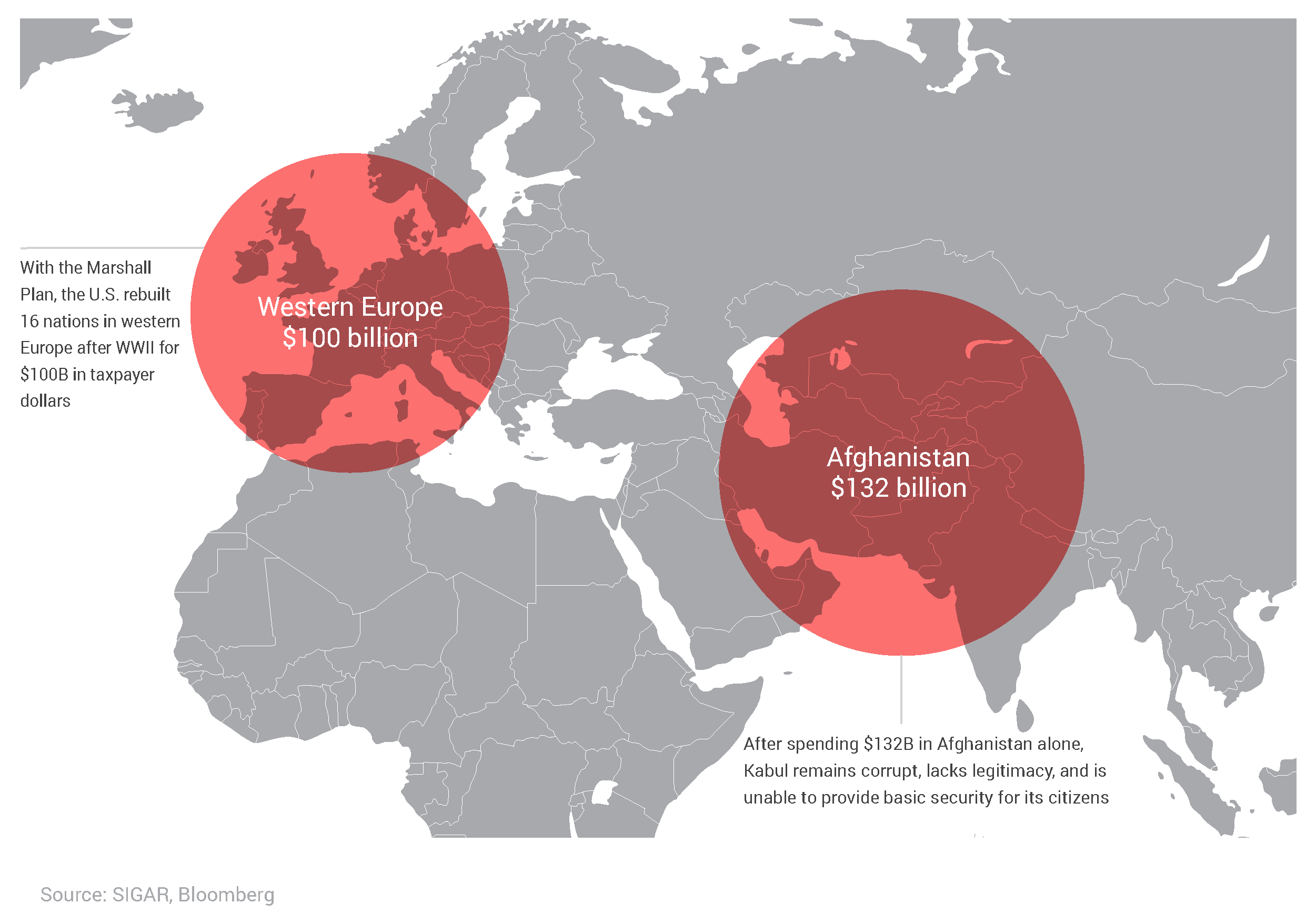

Nearly 18 years later, the failure of this second phase of the U.S. war in Afghanistan is evident. Taliban forces control more territory than they have at any point since 2001. Corruption and ethnic conflict plague the national government, and it remains deeply dependent on foreign aid. Massive investments by the United States and other donor nations—on a scale exceeding spending on the Marshall Plan after World War II—have not translated to meaningful political progress. Continuous foreign training and funding has not significantly improved the Afghan security forces (the national police and military). Attrition in battle and desertion because of low morale deprive the security forces of manpower. Insider attacks on foreign trainers remain frequent, and the sexual abuse of children remains widespread among commanders.

Despite these failures in nation building, Afghanistan has not re-emerged as a base for anti-American terrorism. Although jihadist terrorists are not totally absent, three developments prevent them from finding the sort of safe haven they enjoyed before the U.S. invasion. First, the U.S. military has vastly improved its ability to track and kill terrorists by raid, bombardment, and drone strikes. Second, U.S. political will to use these tools to attack terrorist bases remains high. Third, the Taliban learned something from its fall and remains largely deterred from letting Al-Qaeda operate in its midst. None of these factors depend on the presence of substantial U.S. ground forces.

The removal of U.S. forces should not depend on negotiations with the Taliban. True, there is symbolic value in having written assurances from the Taliban that they will not permit international terrorists to operate in Afghanistan, a goal the United States is now pursuing in talks. But the threat of U.S. forces returning to punish the Taliban if they host terrorists is a deterrent regardless of whether an agreement enshrines it. Nor should U.S. withdrawal turn on expectations about how Afghanistan’s government will fare.

The war has shown Kabul’s success is unachievable for Washington but also unnecessary for U.S. security. It is true that, at least in the short term, U.S. troop withdrawal will degrade the Afghan military’s ability to hold territory and could destabilize the government. But U.S. tutelage, rather than moving the Afghan state toward self-sufficiency, seems to have kept it infantilized.

Departure might put Afghanistan on an eventual path toward self-sufficiency. It might also spur intra-Afghan negotiations that at least partially settle the civil war that has been raging since long before the U.S. invasion in 2001. And it might cause nearer powers with stronger interests in Afghanistan to take greater responsibility for stability there.

Afghanistan’s weak governance

Afghanistan has little history of effective central governance, at least in the modern era.2On geography as a barrier to central government and cause of civil war, see James D. Fearon and David D. Laitin, “Ethnicity, Insurgency, and Civil War,” American Political Science Review 97, no. 1 (February 2003): 75–90. The nation has suffered nearly 40 years of almost continuous civil war, often with the support of one or another foreign patron. The 19th century kings (or emirs) had limited authority and struggled to suppress continual uprisings, mostly in the western and northern areas where other ethnic groups prevailed.3Ahmed Rashid, Descent into Chaos: The U.S. and the Disaster in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Central Asia (New York: Penguin, 2009), 11. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, when the British had their colonial Raj in India, London saw Afghanistan as a buffer against Russian incursions. But the British never really tried to rule Afghanistan, despite fighting three wars there. They exercised power indirectly by paying off tribal chiefs and emirs.4Rubin, The Fragmentation of Afghanistan, 48–52.

During Afghanistan’s 50 years of stability after declaring independence from Britain in 1919, the central ruler (a king until 1973) exercised limited authority and relied heavily on foreign aid. Most came from the Soviet Union, which focused on developing the Afghan military, as well as the United States, with smaller amounts from European powers.5Rashid, 8. Afghanistan became a classic rentier state, where centralized wealth creates a rent-seeking economy revolving around the favor of ruling elites—except the source of wealth was foreign aid.6Barnett R. Rubin, “Political Elites in Afghanistan: Rentier State Building, Rentier State Wrecking,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 24, no. 1 (Winter 1992): 79.

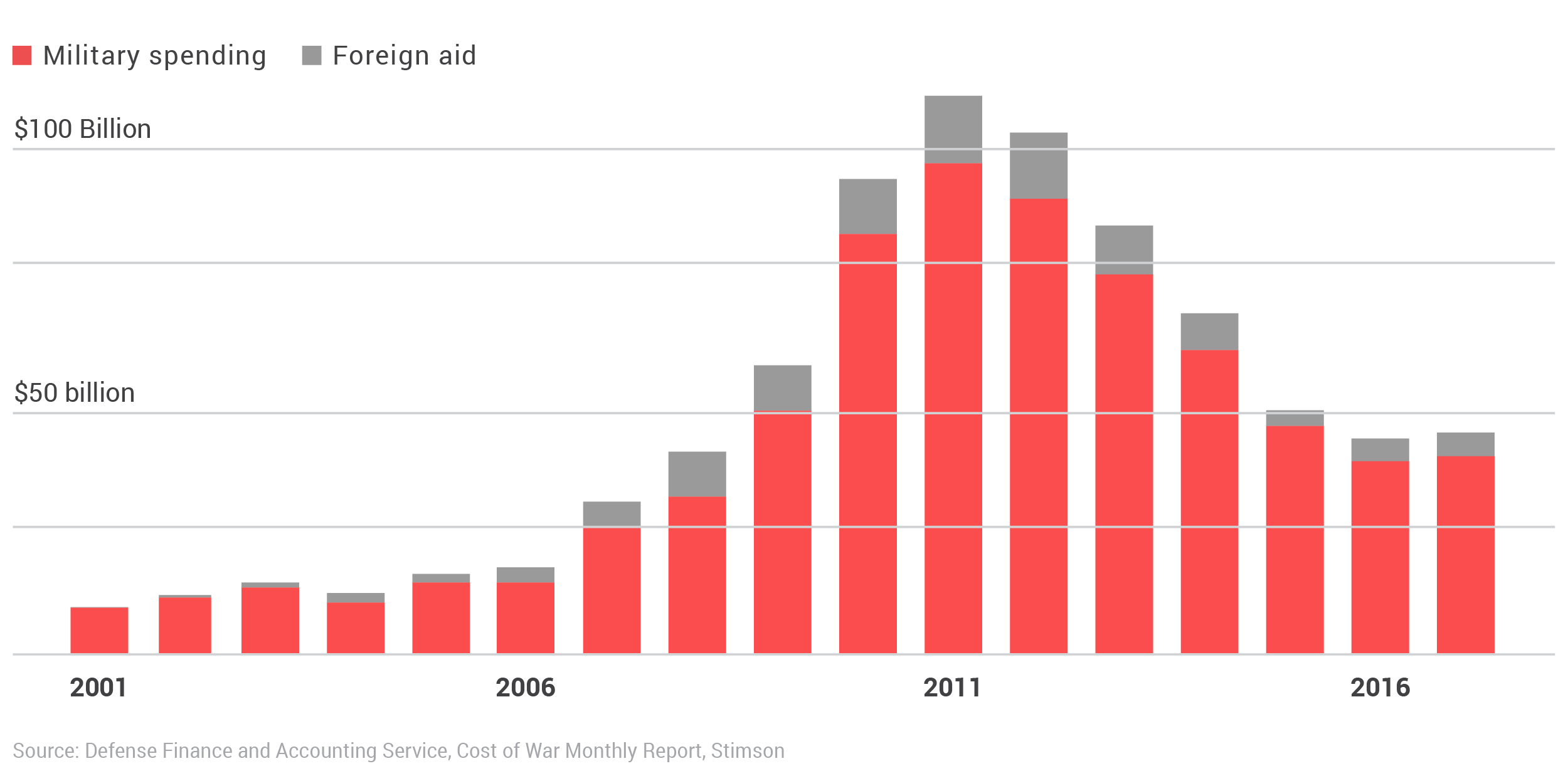

U.S. military and foreign aid spending on Afghanistan

U.S. military spending in Afghanistan from 2001 to 2019 exceeded $700 billion. U.S. foreign aid was approximately $100 billion.

Afghanistan descended into disorder in the 1970s, beginning with the king’s overthrow by his prime minister, Mohmmed Daoud, in 1973. A series of coups and an Islamic rebellion with mild U.S. backing led to the Soviet invasion in late 1979.7“The Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan and the U.S. Response, 1978–1980,” Department of State, Office of the Historian, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1977-1980/soviet-invasion-afghanistan.8Ibid; Douglas MacEachin, Predicting the Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan: The Intelligence Community’s Record (Washington, DC: Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency, 2002). The Soviets would ultimately station 120,000 troops in Afghanistan but could not pacify the country. They withdrew in 1989. The Soviet-installed ruler, Mohammed Najibullah, lasted another three years. His downfall produced warfare among the mujahidin formerly aligned against him. Authority split along militia lines, producing brutal ethnic violence and intensified refugee flows.

These divisions among former rebels, along with Pakistani support, paved the way for the hardline Islamist and predominately Pashtun Taliban, which emerged from the south and took Kabul in 1996.9Anand Gopal, No Good Men Among the Living: America, the Taliban, and the War through Afghan Eyes (New York: Metropolitan, 2014), 64. By 2001, the Taliban had pushed their enemies—the coalition known as the Northern Alliance—into the northeast corner of the country, representing less than 10 percent of its total area. When the United States invaded Afghanistan after the 9/11 attacks, it had already been at war for more than 20 years.

This history does not condemn Afghanistan to perpetual state weakness. But it does augur poorly for sustained peace there, whatever policy the United States pursues. Geography and poverty make continued insurgency in Afghanistan likely, whoever rules. Mountains divide the population, limiting economic and political integration and the reach of government forces. The arid climate and lack of easily extracted resources slow wealth creation and, with it, the state’s ability to gain revenue and build administrative and military capacity.10Only 12 percent of Afghanistan is arable. “Arable Land (% of land area),” World Bank, accessed June 3, 2019, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/AG.LND.ARBL.ZS?locations=AF&view=chart; Afghanistan does have substantial potential to extract minerals, though mining has historically been limited. Mujib Mashal, “Afghanistan Signs Major Mining Deals Despite Legal Concerns,” New York Times, October 6, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/06/world/asia/afghanistan-signs-mining-deals.html; Antony Loewenstein, “Natural Resources Were Supposed to Make Afghanistan Rich. Here’s What’s Happening to Them,” Nation, December 14, 2015, https://www.thenation.com/article/resources-were-supposed-to-make-afghanistan-rich/. Poverty combines with institutional weakness in tax collection to deprive the state of resources. With a gross domestic product (GDP) of $20 billion (below $600 per capita in 2017), Afghanistan is among the world’s poorest countries.11“Afghanistan,” CIA World Factbook, last modified May 24, 2019, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/af.html. That GDP is largely comprised of foreign aid.12One recent estimate is that donor aid accounts for 95 percent of Afghanistan’s GDP. Kenneth Katzman and Clayton Thomas, “Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy,” Congressional Research Service, December 2017, 54, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RL30588.pdf. In 2017, for example, the Afghan government’s revenue was roughly $2 billion despite a budget of $7.3 billion. The difference was covered by foreign aid, most of it from U.S. taxpayers.13Ibid, 6.

Afghanistan’s economic woes encourage division in another way: by providing a large supply of young men available to fight. Afghanistan has low life expectancy—52 years, near the bottom of the global chart—and a high birthrate, resulting in a very young population.14The median age just below 19, and just 6.5 percent of the population is over 55. “Afghanistan,” CIA World Factbook. When combined with high unemployment and a large supply of small arms, this means the ingredients for insurgency are readily available.15On the availability of small arms, see “The Call for Arms Control: Voices from Afghanistan,” Oxfam Briefing Note, January 2006, https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/114616/bn-call-for-tough-arms-control-afghanistan-010106-en.pdf;jsessionid=CFE41F9078C4E429A070CB8F0A10E009?sequence=1, 12-21. On these circumstance as an obstacle to counterinsurgency campaigns, see Barry Posen, “Command of the Commons: The Military Foundation of U.S. Hegemony,” International Security 28. no. 1 (Summer 2003), 30–32.

These circumstances preserve localized political power and undermine Afghan nationalism. Nearly all 33 million Afghans are Muslim (80 percent Hanafi Sunni and 19 percent Shiite), but they are ethnically heterogenous: 42 percent Pashtun, 27 percent Tajik, 9 percent Uzbek, 9 percent Hazara, 4 percent Aimak, 3 percent Turkmen, and 2 percent Baluch. Some of Afghanistan’s ethnic communities, especially the Pashtuns, are also divided along tribal lines, with tribal heads exercising local authority in many areas.16Barnett Rubin, The Fragmentation of Afghanistan: State Formation and Collapse in the International System, 2nd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), 45–48.

Afghanistan’s post-Taliban government has tried to bridge the ethnic divide. Hamid Karzai, who served as the first post-Taliban president until 2014, is Pashtun, as is the current president, Ashraf Ghani. Abdullah Abdullah—the “Chief Executive of Afghanistan,” a position created as part of a U.S.-brokered compromise after the disputed 2014 election—is part Pashtun and part Tajik. The first and second vice presidents are Uzbek and Hazara. Karzai’s deputies were similarly distributed among ethnic groups. Afghanistan’s government leaders have also sought to co-opt tribal heads by giving them government posts and dispensing funds through them.17Kenneth Katzman, “Afghanistan: Politics, Elections, and Government Performance, Congressional Research Service,” January 12, 2015, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RS21922.pdf. That has worked partially, at best.

The U.S. war on Al-Qaeda

The Al-Qaeda network organized by Osama bin Laden came to Afghanistan from Sudan in 1996. They arrived first in Jalalabad, which only subsequently came under Taliban rule, and then largely relocated to the Tarnak Farms base outside Kandahar, a relatively stable area in the south, distant from the front lines. Bin Laden’s fatwas calling for the murder of Americans and Jews and his subsequent press interviews attracted notoriety and recruits from around the world. They began flowing into Al-Qaeda training camps, likely with the help of Pakistani intelligence.18Daniel Benjamin and Steven Simon, Age of Sacred Terror: Radical Islam’s War Against America (New York: Random House, 2002), 140–152. Al-Qaeda reportedly trained 10,000–20,000 radicals in its Afghan camps, with most of them likely returning to Pakistan to serve Kashmiri separatists and other militant organizations there. A smaller portion joined other jihadi groups around the world.19The National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States, The 9/11 Commission Report: Final Report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States (New York: Norton, 2004), 64–67; Rashid, 24–30; 110–11.

Federal prosecutors in New York indicted bin Laden in 1998.20“Indictment: U.S. of America versus Usama Bin Laden,” U.S. District Court, Southern District of New York, Federation of American Scientists, accessed on June 3, 2019, https://fas.org/irp/news/1998/11/indict1.pdf. On pre-9/11 U.S. policies against Al-Qaeda, see especially Steve Coll, Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan, and Bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001 (New York: Penguin Books, 2004). U.S. officials pressed Saudi Arabia, one of three governments that recognized the Taliban’s “Islamic emirate” as Afghanistan’s legitimate government, to force the Taliban to hand him over. Some Taliban leaders had already lost patience with bin Laden, so the Taliban agreed in principle to deliver him to the Saudis and began negotiating the terms. But after Al-Qaeda bombed U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania that summer, Taliban leader Mullah Omar reneged.21Lawrence Wright, The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11 (New York: Vintage, 2006), 266–289.

In 1998, after the embassy bombings, the United States launched a cruise missile attack on Al-Qaeda bases. The Clinton administration boosted support for the Northern Alliance and renewed a suspended plan for a team of Afghans—”tribals”—to try to capture or kill bin Laden.22The 9/11 Commission Report, 126–133. Clinton also considered a special operations raid against Al-Qaeda but was discouraged by the Joint Chiefs and anticipated congressional opposition.23Ibid, 134-37, 189. Richard H. Shultz, Jr, “Show Stoppers.” Weekly Standard, January 26, 2004, https://www.weeklystandard.com/richard-h-shultz-jr/showstoppers. On pre-9/11 efforts to combat Al-Qaeda see Benjamin H. Friedman, “Perception and Power in Counterterrorism: Assessing the American Response to Al Qaeda before September 11,” in American Foreign Policy and the Politics of Fear: Threat Inflations Since 9/11, eds. A. Trevor Thrall and Jane K. Cramer, (New York: Routledge, 2009): 210–229.

After the 9/11 attacks, some in the Taliban wanted to comply with the U.S. demand to hand over bin Laden and his lieutenants, but Mullah Omar again rebuffed them.24Gopal, 12–14; Alex Strick van Linschoten and Felix Kuehn, An Enemy We Created: The Myth of the Taliban-Al-Qaeda Merger in Afghanistan (London: Hurst Publishers, 2012), 4. The U.S. military invaded Afghanistan with only a few thousand troops—U.S. forces there were fewer than 10,000 until the fall of 2002—and provided air support to the Northern Alliance’s ground forces.25Amy Belasco, “Troop Levels in the Afghan and Iraq Wars, FY2001-FY2012: Cost and Other Potential Issues,” Congressional Research Service, July 2, 2009, 62, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/R40682.pdf. By mid-December, the U.S.-backed force had essentially taken all of Afghanistan and toppled the Taliban regime.26Seth Jones, In the Graveyard of Empires: America’s War in Afghanistan (New York: Norton, 2009), 86–96. Rank and file Taliban fighters largely quit and went home.27John Lee Anderson, The Lion’s Grave: Dispatches from Afghanistan (New York: Grove Press, 2002), 153; Gopal, 109. Airstrikes killed much of the Al-Qaeda core, while the rest fled into hiding, mostly in Pakistan.

Washington expands its ambitions

In 2002, a stable peace seemed attainable. The Karzai government was popular across the country, and Taliban leaders mostly sought to cut amnesty deals with Kabul.28Gopal, 104-105; van Linschoten and Kuehn, An Enemy We Created, 6–7.The United States, in retrospect, was well-positioned to begin an orderly withdrawal.

It is too much to say the Taliban’s reemergence was inevitable. Still, given Afghanistan’s chronic problems, avoiding insurgency entirely would have taken very deft governing in Kabul. That was lacking. The Karzai government’s appointment of family and tribal loyalists in the south tended to alienate rival networks, which the state lacked the strength to suppress.29Carl Forsberg, “Power and Politics in Kandahar,” Institute for the Study of War (April 2010), http://www.understandingwar.org/sites/default/files/Politics_and_Power_in_Kandahar.pdf. And the Bush administration’s “with us or against us” policy kept the Taliban excluded as outlaws who could not integrate into the Afghan polity. The small U.S. force relied heavily on local power brokers whose feuds, corruption, and vendettas tended to alienate the public, especially in the south. The intelligence they provided often made the United States “an unknowing instrument of local feuds and power struggles.”30van Linschoten and Kuehn, An Enemy We Created, 6.

The Taliban leadership gradually reorganized in Quetta, Pakistan, with the help of Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI).31Sahar Khan, “Double Game: Why Pakistan Supports Militants and Resists U.S. Pressure to Stop,” Cato Policy Analysis, no. 849. September 20, 2018. It launched a new insurgency, starting with pamphlets (known as night letters) denouncing the Afghan government and escalating to attacks on Afghan security forces as well as acts of terrorism.32Gopal 101–104. The role of Mullah Omar in this body is unclear. U.S. intelligence reports consistently suggested he was based in Pakistan running the movement before his 2013 death by illness, but a recent report, which is disputed, claims he remained in Afghanistan and ceded his leadership role early on; that is, he was a figurehead. Bette Dam, The Secret Life of Mullah Omar; Zomia Center (February 2019); James Reini, “Mullah Omar in Afghanistan Book Claims ‘Not Credible’: Official,” al Jazeera, March 12, 2019, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/03/mulllah-omar-afghanistan-book-claims-credible-official-190312133239892.html. The Taliban then was more like an aligned group of militias than a strict hierarchical entity. Commanders were only partially answerable to top leadership, and Taliban militias regularly clashed with one another. This decentralized Taliban was joined in revolt by other militants who had separate command structures, most notably the Haqqani network, based in Waziristan, which was more closely linked with Al-Qaeda.33A third Taliban faction, Hezb Islami, led by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, became active in the insurgency the late 2000s but remained more independent and cut a peace deal with Afghan government in 2016. Bismellah Alizada, “What Gulbuddin Hekmatyar’s Return Means for Afghanistan,” The Diplomat, May 3, 2017.

The Bush administration initially sought to constrain the scope of the mission in Afghanistan.34Jones, In the Graveyard of Empires, 109–133. The conventional phase of the war included fewer than 10,000 deployed U.S. troops.35Belasco, “Troop Levels in the Afghan and Iraq Wars,” 62. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld in particular pushed to hand over nation-building missions to allies, shorten the mission, and shift U.S. attention to Iraq.36Rashid, Descent into Chaos, LIII. Even so, troop numbers gradually grew as the counterinsurgency campaign took shape. Washington’s ambitions expanded further once Secretary of Defense Robert Gates replaced Rumsfeld in 2006. There were about 25,000 U.S. forces in Afghanistan when President Barack Obama took office in 2009.37Belasco, “Troop Levels in the Afghan and Iraq Wars,” 63.

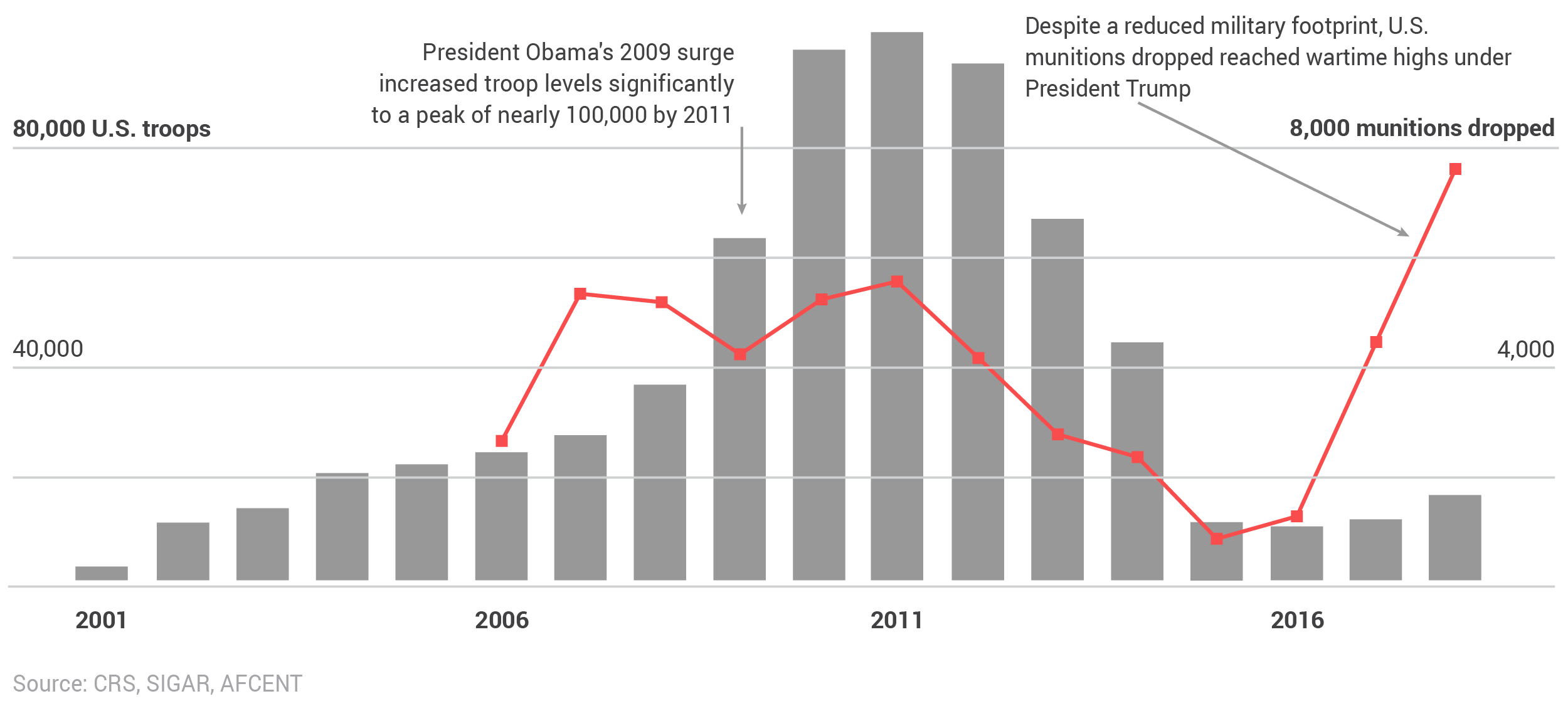

U.S. troop levels and munitions dropped

In December 2001, the United Nations authorized an International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) to provide security in and around Kabul. It was initially manned by about 5,000 troops, mostly from European nations, with the British forming the largest contingent.38Rashid, Descent into Chaos, 132–133. In 2003, NATO took command of ISAF as it expanded its presence across Afghanistan and ran provincial reconstruction teams that were to be the centerpiece of building up local authority and helping counterinsurgency efforts. ISAF grew to include more than 30,000 troops by 2006 and more than 55,000 in 2009.39“NATO and Afghanistan,” NATO, last modified March 5, 2019, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_8189.htm. The U.S. military provided a portion of ISAF troops, meaning U.S. forces in Afghanistan were divided into two efforts. In 2008, command of these efforts was unified under a single U.S. general.40“International Security Assistance Force (ISAF),” Institute for the Study of War, accessed June 3, 2019, http://www.understandingwar.org/international-security-assistance-force-isaf.

Obama took office in 2009 having campaigned on the idea, then popular in Washington, that the U.S. effort in Iraq had led to neglect of the war in Afghanistan.41Barack Obama, “Obama’s Remarks on Iraq and Afghanistan,” New York Times, July 15, 2008, https://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/15/us/politics/15text-obama.html. After a lengthy review process and considerable debate, he took the advice of his military commanders, including the commander in Afghanistan, Stanley McChrystal, and authorized a “surge,” which increased troop levels to nearly 100,000 by 2011.42Ewen MacAskill, “Barack Obama Sets Out New Strategy for Afghanistan War,” Guardian, March 27, 2009, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/mar/27/obama-new-strategy-afghanistan-war.

The faulty logic of the surge assumed counterterrorism depended on counterinsurgency. Terrorism was diagnosed as purely a symptom of weak states torn up by civil wars.43Michael J. Mazarr, “The Rise and Fall of the Failed-State Paradigm: Requiem for a Decade of Distraction,” Foreign Affairs (January/February 2014), https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2013-12-06/rise-and-fall-failed-state-paradigm; Susan E. Rice, “The New National Security Strategy: Focus on Failed States,” Brookings Institution, February 19, 2003, https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-new-national-security-strategy-focus-on-failed-states/. One could attack and kill terrorists, but without addressing the underlying problem of state failure, this thinking posited, tactical success would prove ephemeral and terrorist organizations would restore themselves amid insurgency, like grass growing back after mowing.44Austin Long, “Whack-a-Mole or Coup de Grace? Institutionalization and Leadership Targeting in Iraq and Afghanistan,” Security Studies, 23, no. 3 (Fall 2014): 471–512.

Building state power demanded counterinsurgency, as articulated in Field Manual 3-24, which was written by Generals David Petraeus, who took over for McChrystal after his firing for insubordination, and James Mattis, who would become President Donald Trump’s first Secretary of Defense.45“Army Field Manual 3-24: Counterinsurgency,” U.S. Department of the Army, December 2006, accessed June 3, 2019, https://www.hsdl.org/?abstract&did=468442. The argument was that the Afghan state had to win a monopoly on the legitimate use of force by defeating insurgents and their proto-states. It would do that by winning popular support through public protection and the provision of government services, which would undercut popular support for the insurgents and provide intelligence vital to their destruction—a process dubbed “clear, hold, and build.” Of course, the surge meant it would be U.S. troops and funds, rather than the Afghan state, doing most of the work to monopolize the use of force. Obama seemingly reasoned that setting a quick timetable for the surge and a U.S. exit date would spur Kabul to “step up.”46Stephen D. Biddle, “Obama’s Withdrawal Date a Controversial Gambit,” interviewed by Bernard Gwertzman, Council on Foreign Relations, December 1, 2009, https://www.cfr.org/interview/obamas-withdrawal-date-controversial-gambit; Rory Stewart, “Afghanistan: What Could Work,” New York Review of Books, January 14, 2010, https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2010/01/14/afghanistan-what-could-work/.

Despite the surge, the Taliban gained influence over more territory.47“Special Inspector General for Afghan Reconstruction (SIGAR) Quarterly Report to the United States Congress,” SIGAR, July 30, 2018, accessed on June 3, 2019, https://www.sigar.mil/pdf/quarterlyreports/2018-07-30qr.pdf. By 2014, the United States had officially shifted to an advisory mission focused on training the Afghan security forces and on combatting terrorist entities. But the planned withdrawal of U.S. forces was repeatedly delayed due to the inability of Afghan forces to fully take over the counterinsurgency work.48Spencer Ackerman, “Obama Announces Plan to Keep 9,800 US Troops in Afghanistan After 2014,” Guardian, May 27, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/may/27/obama-us-afghanistan-force-2014; Matthew Rosenberg and Michael D. Shear, “In Reversal, Obama Says U.S. Soldiers Will Stay in Afghanistan to 2017,” New York Times, October 15, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/16/world/asia/obama-troop-withdrawal-afghanistan.html.

Before running for president, Trump frequently criticized the U.S. war in Afghanistan on Twitter.49Zack Beauchamp, “The Case Against Trump’s Decision to Keep Fighting in Afghanistan, Explained by Trump,” Vox, August 21, 2017, https://www.vox.com/world/2017/8/21/16178916/trump-afghanistan-withdraw-tweets. He was vague about it as a candidate, but as president he has often expressed skepticism of continuing the war and reportedly even berated his top advisors about the war.50At a July 2017 National Security Council meeting, Trump reportedly told Secretary of Defense James Mattis and General H.R. McMaster, the National Security Advisor: “The soldiers on the ground could run things much better than you…I don’t know what the hell we’re doing…How many more deaths? How many more lost limbs? How much longer are we going to be there?” Philip Rucker and Robert Costa, “Bob Woodward’s New Book Reveals a ‘Nervous Breakdown’ of Trump’s Presidency,” Washington Post, September 4, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/bob-woodwards-new-book-reveals-a-nervous-breakdown-of-trumps-presidency/2018/09/04/b27a389e-ac60-11e8-a8d7-0f63ab8b1370_story.html; On his views as a candidate see Louis Jacobson, “Tracking Donald Trump’s Evolving Positions on Afghanistan,” Politifact, August 22, 2017, https://www.politifact.com/truth-o-meter/article/2017/aug/22/tracking-donald-trump-evolving-position-Afghanista/. The Trump administration, however, loosened the rules of engagement for airstrikes, greatly increasing their frequency (see prior graphic: “U.S. troop levels and munitions dropped”).

In 2017, Trump authorized a “mini-surge” in Afghanistan of more than 3,000 troops. The administration has blocked the release of information on total U.S. troop numbers in Afghanistan, but media reports say it is about 15,000, with around 8,500 assigned to the NATO “train and assist” mission.51David Nakamura and Abby Phillip, “Trump Announces New Strategy for Afghanistan That Calls for A Troop Increase,” Washington Post, August 21, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/trump-expected-to-announce-small-troop-increase-in-afghanistan-in-prime-time-address/2017/08/21/eb3a513e-868a-11e7-a94f-3139abce39f5_story.html. On the troop totals in the NATO mission, see Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, Quarterly Report to the United States Congress, July 30, 2019 https://www.sigar.mil/pdf/quarterlyreports/2019-07-30qr.pdf. Trump justified the decision to send more troops with the standard safe-haven logic offered by war advocates for more than a decade:

The consequences of a rapid exit are both predictable and unacceptable. 9/11, the worst terrorist attack in our history, was planned and directed from Afghanistan because that country was ruled by a government that gave comfort and shelter to terrorists. A hasty withdrawal would create a vacuum that terrorists, including ISIS and Al-Qaeda, would instantly fill, just as happened before September 11th.52Donald Trump, “Remarks by President Trump on the Strategy in Afghanistan and South Asia,” The White House, August 21, 2017, accessed June 3, 2019, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-strategy-afghanistan-south-asia/.

Trump also argued U.S. troops would prevent regional instability, including in nuclear-armed Pakistan, and produce “an honorable and enduring outcome” worthy of the nation’s and the military’s sacrifices.53Ibid. In that final argument are hints of a larger rationale: the idea that U.S. negotiating leverage with the Taliban requires military progress. The thinking, which the administration might want to avoid expressing publicly, is that a demonstration of will and commitment would make the Taliban more eager to negotiate on U.S. withdrawal and facilitate a power-sharing agreement, even if it does not reverse battlefield failures. Consistent with this logic, the Trump administration resumed direct talks with the Taliban, which had sputtered under Obama, tapping former U.S. Ambassador to Afghanistan Zalmay Khalilzad to lead them.54Associated Press, “US Appoints Veteran Envoy for Afghan Peace Effort,” Voice of America News, September 4, 2018, https://www.voanews.com/a/us-appoints-veteran-envoy-for-afghan-peace-effort/4557805.html.

In the last year, the Trump administration pivoted back toward skepticism about nation building in Afghanistan. News reports in late 2018 suggested the president was planning to reduce the U.S. troop number by half. His 2019 State of the Union Address mentioned the possibility of removing troops as a result of negotiations with the Taliban, insisting “great nations do not fight endless wars.” That sentiment seems consistent with the administration’s National Security Strategy, which ambiguously suggests a pivot to focusing on “great power competition.”55“National Security Strategy of the United States of America,” The White House, December 2017, accessed June 3, 2019, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905.pdf. In recent months, however, Trump shifted rhetorical course yet again, saying U.S. generals had convinced him to keep troops indefinitely in Afghanistan to fight terrorism.56Leo Shane III, “Trump: Pentagon leaders want to keep troops in Afghanistan,” Military Times, July 2, 2019, https://www.militarytimes.com/news/pentagon-congress/2019/07/02/trump-pentagon-leaders-want-to-keep-troops-in-afghanistan/.

State building fails

The U.S. effort at nation building in Afghanistan would not be worthwhile even if it were more successful. Yet in any case, progress is mostly absent. The war is failing to achieve its flawed objectives.

The problem is not simply that the Afghan state and security forces are ethnically fractured, frequently rapacious, and violating human rights, all while failing to defeat the Taliban. Nor is it that the government in Kabul does a poor job collecting taxes and providing services. The larger problem is Afghanistan’s lack of progress in reversing these failings and moving toward self-sufficiency.

After 40 years of frequent civil war, consolidated central rule is unlikely in Afghanistan regardless of the presence of U.S. forces. If the current government cuts a peace deal with the Taliban, it is probable that some factions will continue to fight. If the Taliban managed to retake Kabul after a U.S. withdrawal—which is possible but unlikely in the near term—they would likely face continued resistance from the non-Pashtun population and some elements of their insurgency. Any negotiated settlement is likely to be partial and shaky.

Before showing that nation building progress is absent, two points about metrics of success in counterinsurgency are useful. First, metrics of success for military campaigns should generally be taken with a grain of salt. Most wars are competitions in coercion settled by negotiation. Each side’s willingness to accommodate the other’s demands may not reliably correspond to measurable success on the battlefield. That is especially true of insurgencies, where the balance of will is crucial and often only vaguely related to the balance of military power.

Second, U.S. metrics of successful counterinsurgency are overly reflective of U.S. values. The state defeating rebels by winning hearts and minds through the provision of services is a liberal or progressive approach.57Edward Luttwak, “Dead End: Counterinsurgency Warfare as Military Malpractice,” Harper’s Magazine, February 2007, https://harpers.org/archive/2007/02/dead-end/. Successful counterinsurgencies are often considerably more coercive, involving mass resettlement and widespread violence used to force people to switch sides.58Paul Staniland, “States, Insurgents, and Wartime Political Orders,” Perspectives on Politics 10, no. 2 (June 2012), 243–264. Because the U.S. public likely would not tolerate such tactics without a threat to the United States greater than foreign insurgents can pose, these tactics are largely unavailable to the U.S. military.59Eliot A. Cohen, “Constraints on America’s Conduct of Small Wars,” International Security 9, no. 2 (Fall, 1984), 151–181. Still, counterinsurgents might co-opt some insurgents, allowing them significant autonomy and winning popular acquiescence to the bargain without achieving the success in governance the U.S. approach says is essential.

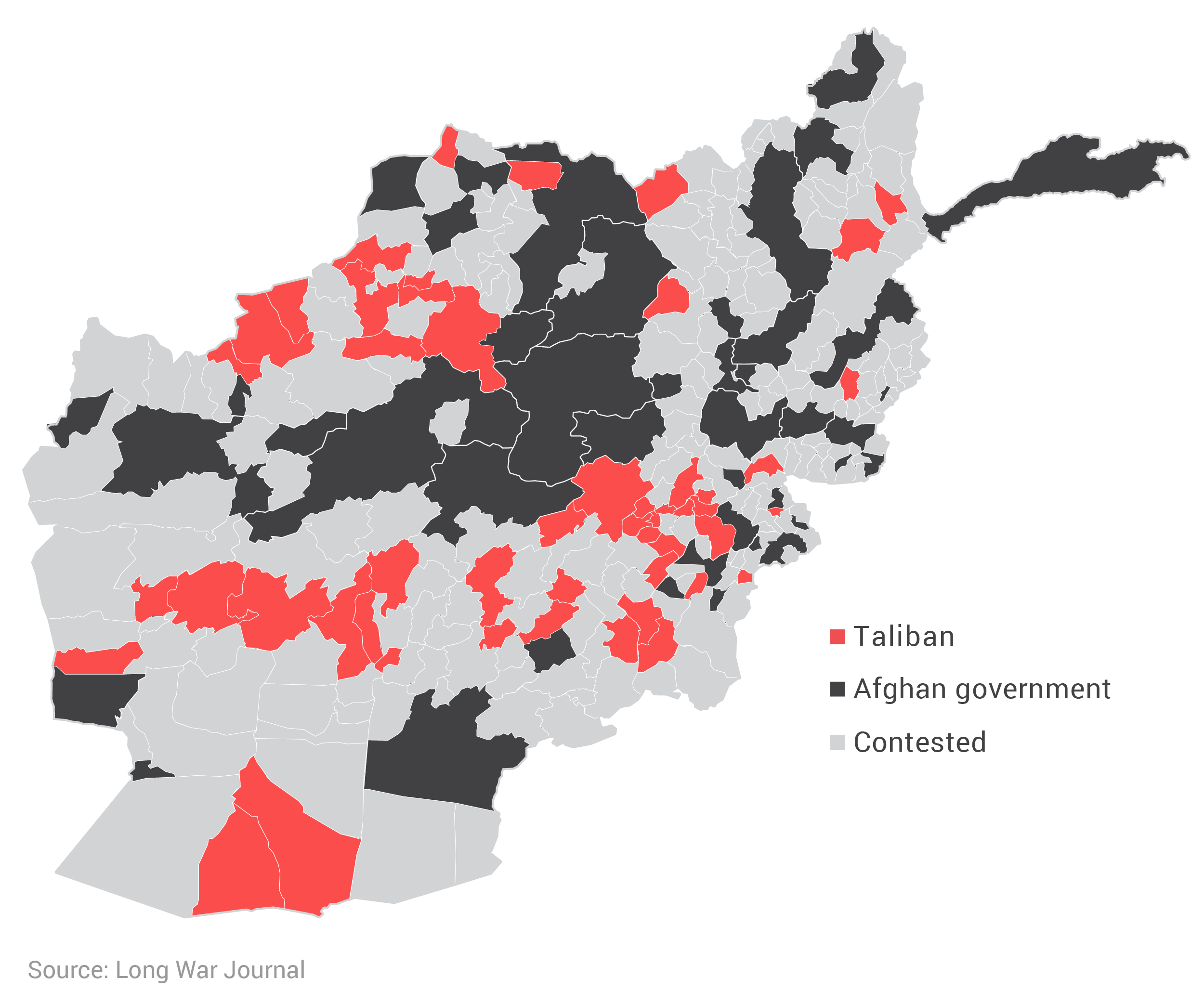

The war in Afghanistan is clearly failing to achieve the aims its advocates say are essential to success. U.S. commanders have repeatedly stated victory in Afghanistan is a question of giving them more time and resources.60Clayton Thomas, “Afghanistan: Background and U.S. Policy in Brief,” Congressional Research Service, August 3, 2018, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R45122.pdf. But time has not helped much, and the story of the benchmarks measuring progress is one of stasis or outright failure.61“Report of July 30, 2018,” SIGAR. Even the recently departed commander of U.S. Forces there, John Nicholson called for an end to the U.S. war upon his departure. Mujib Mashal, “‘Time for This War in Afghanistan to End,’ Says Departing U.S. Commander,” New York Times, September 2, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/02/world/asia/afghan-commander-us-john-nicholson.html. According to a July 2018 report by the Special Inspector General for Afghan Reconstruction (SIGAR), the Taliban contest or control 44 percent of Afghan districts, more than at any point since 2001—about a 50 percent gain from the year before Obama’s surge.62“Report of July 30, 2018,” SIGAR. In recent years, the Taliban have launched increasingly large operations and briefly seized cities: Kunduz in 2015 and Farah and Ghazni in 2018.

Afghanistan territorial control by province

U.S. efforts to cut off two major sources of support for the Taliban have largely failed. Although the details are murky, Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) still seems to support the Taliban.63On ISI support for the Taliban, see especially Carlotta Gall, The Wrong Enemy: America in Afghanistan, 2001–2014 (Boston: Mariner Books, 2015); Vanda Felbab-Brown, “Why Pakistan Supports Terrorist Groups, and Why the US finds it so Hard to Induce Change,” Brookings Institution, January 5, 2018, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2018/01/05/why-pakistan-supports-terrorist-groups-and-why-the-us-finds-it-so-hard-to-induce-change/. And U.S. efforts to curb the poppy cultivation that funds the Taliban have essentially failed, with cultivation and opium production near record levels.64Katzman and Thomas, “Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy,” 23.

The results of the decade-and-a-half long effort to train the Afghan security services are dismal, demonstrating the difficulty of building effective security forces on a shaky state foundation.65Mara Karlin, “Why Military Assistance Programs Disappoint: Minor Tools Can’t Solve Major Problems,” Foreign Affairs (November/December 2017). The United States has spent $72.8 billion and counting on this effort since 2002, and American taxpayers provide 75 percent of Afghanistan’s annual security budget of $5 billion (the rest comes largely from NATO allies).66Thomas, “Afghanistan: Background and U.S. Policy in Brief,” 7. The Pentagon budget documents justifying this funding annually insist Afghan forces are headed toward sustainability—presumably meaning a time when Afghanistan can pay for its own troops.67The most recent is “Justification for FY 2020 Overseas Contingency Operations Afghanistan Security Forces Fund,” Office of the Secretary of Defense, Department of Defense Budget Fiscal Year 2020 (March 2019), https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/fy2020/fy2020_ASFF_Justification_Book.pdf. But with U.S. costs now as high as ever, that is not occurring, nor is there any indication it ever will.

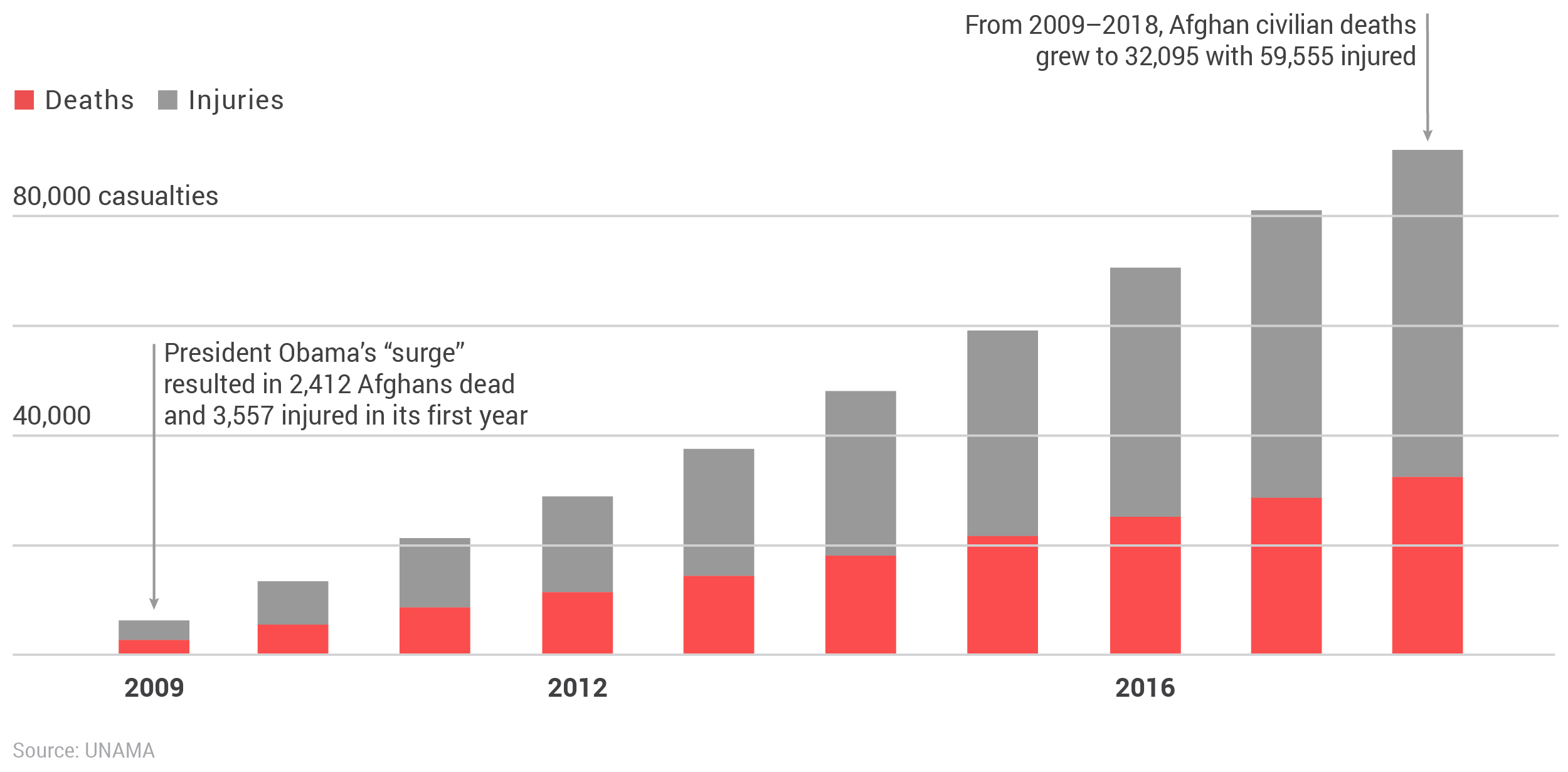

In recent years, the Afghan security forces have lost troops at a likely unsustainable rate: 5,500 were killed in 2015; 6,700 in 2016; and probably 10,000 in 2017 (the number was classified).68Katzman and Thomas, “Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy,” 31. Afghan security forces have lately suffered 30 to 40 casualties every day, undermining recruiting efforts despite the economic downturn since 2013.69Vanda Felbab-Brown, “Ballots and Bullets in Afghanistan,“ Brookings Institution, October 23, 2018, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2018/10/23/ballots-and-bullets-in-afghanistan/. Absenteeism and desertion remain major problems, costing the Afghan military about 10 percent of its manpower in 2017.70Ahmed Rashid, “In Kabul Echoes of Saigon,” New York Review of Books, August 28, 2018, https://www.nybooks.com/daily/2018/08/28/in-kabul-echoes-of-saigon/. More than one-third of the remainder elected not to re-enlist.71“Report of July 30, 2018,” SIGAR. Overall, the Afghan National Army has to replace 36 percent of its manpower monthly—a rate of attrition that even new CENTCOM Commander General Kenneth McKenzie conceded is not sustainable.72Elizabeth Mclaughlin, “Afghan Troop Losses ‘Not Sustainable,’ Says Nominee to Command U.S. troops in Middle East,” ABC News, December 4, 2018, https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/nominee-command-us-troops-middle-east-afghan-troop/story?id=59606850. Afghan forces, aided by U.S. forces and airstrikes, also produce the majority of civilian casualties, creating popular resentment.73Mujib Mashal, “Afghan and U.S. Forces Blamed for Killing More Civilians This Year Than Taliban Have,” New York Times, June 30, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/30/world/asia/afghanistan-civilian-casualties.html.

Cumulative civilian casualties in Afghanistan (2009–2018)

The security services are prone to criminality and human rights abuses. The Afghan National Police—a paramilitary organization that operates more like a military organization than a Western-style police force—is notorious for its predatory practices and corruption.74Gopal, 135; 189. Its desertion and attrition rates are even higher than the military’s, with about half the force either quitting or being lost to casualties annually by one recent estimate.75Katzman and Thomas, “Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy,” 35; Thomas, “Afghanistan: Background and U.S. Policy in Brief,” 9. Among military commanders and other well-placed U.S allies, the practice of keeping children as sexual objects continues.76“Implementation of the Leahy Law Regarding Allegations of Child Sexual Abuse by Members of the Afghan National Defense and Security Force,” Inspector General, U.S. Department of Defense, November 16, 2017, accessed on June 3, 2019, https://media.defense.gov/2017/Nov/15/2001843802/-1/-1/1/DODIG-2018-018_CHILD_SEXUAL_ABUSE_V2_508_R_REDACTED.pdf.

The tendency of Afghan military trainees to shoot their Western trainers likewise remains a major issue and has caused U.S. officials to limit contact with Afghan forces.77Pamela Constable, “U.S. Military Scales Back Contacts with Afghans After ‘Insider’ Shootings,” Washington Post, October 24, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/us-military-scales-back-contacts-with-afghans-after-insider-shootings/2018/10/24/69ba2682-d794-11e8-8384-bcc5492fef49_story.html. There were 96 insider attacks on U.S. or NATO trainers between 2008 and the end of 2017, with 152 foreign troops killed and 200 wounded.78Bill Roggio and Lisa Lundquist, “Green-on-Blue Attacks in Afghanistan: The Data,” Long War Journal, June 17, 2017, https://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2012/08/green-on-blue_attack.php#data. Though these attacks have slowed in recent years, they continue to occur regularly.

Metrics on governance are also discouraging. Afghanistan remains one the world’s most corrupt nations, according to numerous reports.79“Corruption & Anti-Corruption Issues in Afghanistan,” Civil-Military Fusion Centre, February 2012, accessed June 3, 2019, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/CFC-Afghanistan-Corruption-Volume-Feb2012.pdf; J. P. Lawrence, “Afghan Anti-Corruption Program Is Corrupt, US Officials Say,” Stars and Stripes, November 9, 2018, https://www.stripes.com/news/afghan-anti-corruption-program-is-corrupt-us-officials-say-1.555894; Vanda Felbab-Brown, “How Predatory Crime and Corruption in Afghanistan Underpin the Taliban Insurgency,” Brookings Institution, April 18, 2017, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2017/04/18/how-predatory-crime-and-corruption-in-afghanistan-underpin-the-taliban-insurgency/. The government remains almost wholly dependent on foreign aid for its entire budget, indicating a lack of progress towards self-sufficiency.

A bright spot, arguably, is elections. Afghans continue to vote in high numbers when given the opportunity, despite regular attacks at polling places. But in the parliamentary elections of October 2018, which were delayed two years, around one-third of polling stations could not open because of insecurity.80Felbab-Brown, “Ballots and Bullets in Afghanistan.” Allegations of widespread fraud clouded the last two presidential elections. The 2014 presidential election produced a deadlock between Abdullah and Ghani’s factions, which was eventually resolved by a U.S.-brokered deal.81Lesley Wroughton and Maria Golovnina, “An Embrace and a Handshake: How John Kerry Brokered Peace between Afghan Rivals, Reuters, July 13, 2014, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-afghanistan-election-kerry/an-embrace-and-a-handshake-how-john-kerry-brokered-peace-between-afghan-rivals-idUSKBN0FI0RA20140713. Ethnic divisions have sharpened in the last several years, and the popular legitimacy of the government is increasingly tenuous, even in regions it controls.82Frud Bezhan, “Leaked Memo Fuels New Allegations of Ethnic Bias in Afghan Government,” RFERL, November 20, 2017; Scott DesMarais, “Afghan Government on Shaky Ground Ahead of Elections,” Institute for the Study of War, July 31, 2018, http://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/afghan-government-shaky-ground-ahead-elections.

The failure of counterinsurgency is a reason to reject the argument that keeping troops in Afghanistan indefinitely is needed to protect Afghan human rights. Sadly, they are not well-protected now thanks to the government’s failure to control much of the country and its failure to govern decently where it does exercise control. It is true that a U.S. withdrawal could undermine progress in access to services, education, and other areas where women have achieved gains in regions controlled by Kabul.83Ryan Crocker, “The U.S. Is Surrendering to the Taliban,” Washington Post, January 30, 2019. But rapacious police, officials who murder rivals and torture prisoners, and a largely dysfunctional legal system mean the Afghan government is only a marginally better exemplar of human rights than the Taliban.84Anderson et al. Besides that, the Taliban’s commitment to hardline policies, like keeping girls out of schools, seems to have diminished.85Frud Bezhan, “Afghan Taliban Open to Women’s Rights—But Only on Its Terms,” RFERL, February 06, 2019, https://www.rferl.org/a/taliban-afghanistan-open-women-s-rights-only-terms/29755102.html.

U.S. foreign aid to Afghanistan vs. Marshall Plan spending (present dollars)

Some see this litany of counterinsurgency defeats as insufficient evidence of failure. The United States, they maintain, need only tread water in Afghanistan, keeping the government in Kabul afloat and semi-functional. The war is sustainable, they say.86Jeff M. Smith, “Why America Cannot Afford to Pull Out of Afghanistan,” Heritage Foundation, January 2, 2019, https://www.heritage.org/middle-east/commentary/why-america-cannot-afford-pull-out-afghanistan; Max Boot, “Why Winning and Losing Are Irrelevant in Syria and Afghanistan,” Washington Post, January 30, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/global-opinions/the-us-cant-win-the-wars-in-afghanistan-and-syria–but-we-can-lose-them/2019/01/30/e440c54e-23ea-11e9-90cd-dedb0c92dc17_story.html. Its cost, now officially $45 billion annually, is relatively low given the Pentagon budget in excess of $700 billion. In this view, the war in Afghanistan is like policing, an ongoing function aimed at suppressing an ongoing harm, and is cheap enough to continue perpetually.

The response to that argument is that lots of foolhardy polices are perfectly sustainable for a state as rich as the United States—but justifying them requires proof their benefits outweigh their costs. The question is not whether losing a handful of servicemembers annually (15 have died in combat so far in 2019) and spending tens of billions a year is unaffordable, but whether those costs are worthwhile. Would they have done more for U.S. welfare or security if used otherwise? Hardly any of the U.S. costs in Afghanistan are actually producing a security gain by reducing the risk of terrorism. The effort is a massive loser from a cost-benefit standpoint, even aside from the corrosive effects that perpetual deficit-funded interventions have on American public policy, civic life, and civil-military relations.87For a look at deficit financing of wars and its corrupting effect on American strategic culture, see Sarah E. Kreps, Taxing Wars: The American Way of War Finance and the Decline of Democracy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Counterterrorism vs. counterinsurgency

The tendency to expand counterterrorism into counterinsurgency missions may make sense at a glance, but it does not survive scrutiny. The violent tools of counterterrorism do not settle the political fractures that lead to the conditions conducive to terrorist organizations. Strikes and raids get the United States into these fights but cannot resolve them. This is one reason why none of the various U.S. drone campaigns have yet ended.88Benjamin H. Friedman, “Rethinking Drone Warfare,” in Our Foreign Policy Choices: Rethinking America’s Global Role, eds. Christopher Preble, Emma Ashford, and Travis Evans (Washington, D.C.: Cato Institute, 2016), 79–84, https://object.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/pubs/pdf/our-foreign-policy-choices-white-paper.pdf. That said, as of this writing, no drone strike had occurred in Pakistan in more than a year. Counterinsurgency offers a specious way to solve this problem of irresolution and attaches counterterrorism to other governance goals that can make it seem more palatable.

By contrast, pure counterterrorism campaigns can successfully keep terrorists on their heels, disrupting the meeting, training, and other acts of organizational maintenance that make them effective purveyors of distant violence.89A good overview of the literature on the effectiveness of drone strikes is James I. Walsh, The Effectiveness of Drone Strikes in Counterinsurgency and Counterterrorism Campaigns (Carlisle, PA: Army War College Strategic Studies Institute, 2013). In cases where the terrorist organization is distinguishable from the insurgency and lacks broad popular support, brute force efforts to eradicate it may succeed either by driving it out of the contested territory or simply eradicating its members, who will be difficult to replace in that circumstance. Something along those lines seems to have happened to the Islamic State (ISIS) in Libya.90Oliver Imhof and Osama Mansour, “The Last Days of ISIS’ Libya Stronghold,” Daily Beast, July 5, 2018, https://www.thedailybeast.com/the-last-days-of-isis-libya-stronghold. Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan arguably suffered a similar fate after the U.S. invasion.91Fawaz A. Gerges, The Rise and Fall of Al-Qaeda, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).

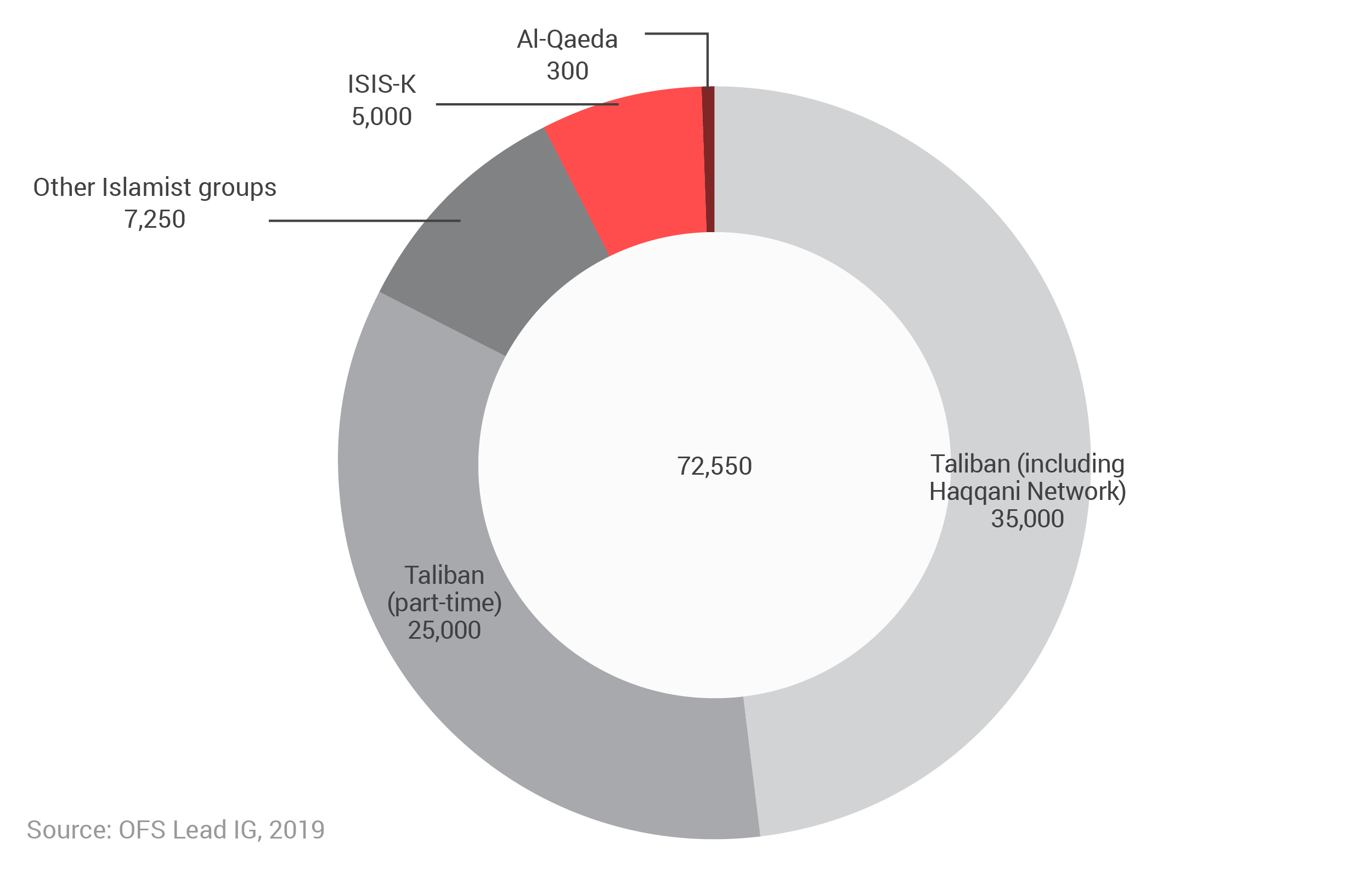

U.S. estimates of enemy forces in Afghanistan

Contrary to the belief of the architects of the U.S. war effort, the failure of counterinsurgency has not made Afghanistan into a base for international terrorists.

That is not to say it is entirely free of jihadi Al-Qaeda sympathizers or terrorism. Some number of Al-Qaeda-linked terrorists continue to operate there, and ISIS has gained a small foothold.92“Twenty-third Report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team Submitted Pursuant to Resolution 2368 (2017) concerning ISIL (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and Associated Individuals and Entities,” United Nations Security Council, January 15, 2019, accessed on June 3, 2019, https://www.un.org/sc/ctc/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/N1846950_EN.pdf. Last year, Kabul suffered a series of suicide bombing attacks, some claimed by ISIS, some by the Taliban.93Diaa Hadid and Scott Neuman, “Suicide Bombers in Kabul Attack Multiple Police Stations,” NPR, May 9, 2018, https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2018/05/09/609654597/suicide-bombers-in-kabul-attack-multiple-police-stations; Sharif Hassan, “Death Toll Rises in Suicide Bombing of Islamic Gathering in Kabul,” Washington Post, November 21, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/death-toll-rises-in-suicide-bombing-of-islamic-gathering-in-kabul/2018/11/21/1e30b348-ed9c-11e8-8679-934a2b33be52_story.html. The United States also attacked what commanders said were several Al-Qaeda training facilities.94Dam Lamothe, “‘Probably the Largest’ Al-Qaeda Training Camp Ever Destroyed in Afghanistan,” Washington Post, October 30, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/checkpoint/wp/2015/10/30/probably-the-largest-al-qaeda-training-camp-ever-destroyed-in-afghanistan/. But while terrorism remains a problem in Afghanistan, it is largely perpetrated by the Taliban as part of their insurgency.

ISIS-K, the Afghan entity claiming adherence to the Islamic State, has conducted a number of bloody attacks. But it appears to be a renegade Taliban offshoot that decided to attach itself to the Islamic State’s brand without having operational links to the organization headquartered in Syria. It has itself come under attack by the Taliban, which likewise distanced itself from Al-Qaeda, even before recent U.S. talks.95van Linschoten and Kuehn, An Enemy We Created, 7–9.

As in other civil wars, the line between insurgency and terrorism can be blurry in Afghanistan. What is clear, however, is that terrorists have not found a haven in Afghanistan in which to organize attacks on the West.

Since 2001, no terrorist plot organized in Afghanistan has targeted the United States. Some terrorists have claimed resistance to the U.S. war effort as inspiration, but that is another matter.96Robert A. Pape, Dying To Win: The Strategic Logic of Suicide Terrorism (New York: Random House, 2005). Indeed, Al-Qaeda proper has had little success in attacking the U.S. since it was dispersed from Afghanistan following the 2001 invasion.97John Mueller, ed., Terrorism since 9/11: The American Cases (Columbus, OH: Mershon Center for International Security Studies, January 2018). Today, whatever organizational capacity it retains is centered in Pakistan, not Afghanistan—in Taliban-friendly territory or otherwise.

Causes of counterterrorism success

First, Al-Qaeda succeeded in carrying out the 9/11 attacks less because it was such an effective and dangerous entity than because it was operating in a relatively permissive security environment.98Jason Burke, Al-Qaeda: Casting a Shadow of Terror (London: I.B. Tauris 2003); John Mueller, “Six Rather Unusual Propositions about Terrorism,” Terrorism and Political Violence 17 (Autumn 2005), 487–505. Most of its operatives were amateurish, contrary to the popular notion of an organizationally-adept, form-shifting, WMD-producing entity. Its ideology was resilient, but its organization was weak and brittle.

Second, the United States has massively improved its ability to track and target terrorists remotely since 2001.99Jon R. Lindsay, “Reinventing the Revolution: Technological Visions, Counterinsurgent Criticism, and the Rise of Special Operations,” Journal of Strategic Studies (February 2013): 1–32; Asfandyar Mir, “What Explains Counterterrorism Effectiveness? Evidence from the U.S. Drone War in Pakistan,” International Security (Fall 2018): 45–83. The 9/11 attacks occurred just as the U.S. military was learning to arm unmanned aircraft with Hellfire missiles. Drones’ surveillance capability, the marriage of that capability with airstrike capability, and the organizational capacity to quickly process intelligence information for strikes or raids has substantially increased the U.S. military’s ability to target people without local deployments of U.S. forces. True, this collective capability is not the silver bullet some leaders make it out to be, and it can be overly seductive. But it is a serious detriment to anti-American organizations’ ability to mass and train as Al-Qaeda once did in Afghanistan.

Third, the United States today has greater will to launch airstrikes and raids on terrorists. The Joint Chiefs were not eager to launch a raid or sustained airstrikes against Al-Qaeda before the 9/11 attacks, and Congress was not critical of their reluctance.100Benjamin and Simon, Age of Sacred Terror, 358–363. Today, things are different. Despite polls showing a war-weary public, there is little doubt about Washington’s willingness to launch raids or strikes on terrorists plotting to kill Americans.

Fourth, the Taliban learned from 2001. Most of their senior leaders, if not their mid-level commanders who control militia-type forces, are well aware the United States lacks tolerance for those who accept international terrorists.101Joshua Rovner and Austin Long, “Dominoes on the Durand Line? Overcoming Strategic Myths in Afghanistan and Pakistan,” Cato Institute Foreign Policy Briefing No. 92, June 14, 2011, https://object.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/pubs/pdf/fpb92.pdf. Today, the Taliban’s incentive to evict all terrorists from its midst is limited insofar as U.S. forces treat them as interchangeable. But if U.S. forces leave, it should be clear Al-Qaeda or similar actors’ return to Taliban territory will result in their return, at least in the form of airstrikes. This does not mean the Taliban, who remain rather disaggregated, are perfectly deterred from hosting Al-Qaeda types. But their self-interest in keeping such actors out of their midst is worth acknowledging.

The problems with U.S.-led counterinsurgency

The theory linking counterterrorism to counterinsurgency and nation building, which has animated the U.S. war efforts in Afghanistan, rests on faulty assumptions. For one, the idea that terrorism results from failed states is oversimplified.102Justin Logan and Christopher Preble, “Failed States and Flawed Logic: The Case against a Standing Nation-Building Office,” Cato Institute Policy Analysis No. 560, January 11, 2006, https://www.cato.org/publications/policy-analysis/failed-states-flawed-logic-case-against-standing-nationbuilding-office. While terrorist organizations do tend to emerge amid civil wars, plenty of failed states and civil wars produce no such organizations. Even in 1990s Afghanistan, the condition that let Al-Qaeda function was not the absence of a state but the fact that the state aligned with Al-Qaeda.

The other major problem with the theory is that it understates the difficulties of organizing the politics of foreign states by force. The places where the United States undertakes long-term counterterrorism efforts—like Yemen, Somalia, northwest Pakistan, and Iraq—tend to be especially ill-suited to outside efforts to manipulate political change. Foreign attempts to stabilize and modernize such states are likely to require massive costs and produce unintended consequences that swamp the ills they aim to prevent—even if they have a chance to succeed. And most outside state-building attempts fail.103Alexander B. Downes and Jonathan Monten, “Forced to be Free? Why Foreign-Imposed Regime Change Rarely Leads to Democratization,” International Security 37, no. 4 (Spring 2013): 90–131.

There are several good reasons to doubt the United States can ever become proficient at winning other people’s civil wars for them. First, the modest success the United States has against insurgencies seems to defy its stated counterinsurgency theory. During the surge in Iraq’s Anbar province, for example, U.S. forces temporarily pacified the Sunni insurgency largely by paying them off and allowing them to rule in their area, provided they turned against Al-Qaeda in Iraq. Saddam Hussein himself employed this tactic late in his rule.104Austin Long, “The Anbar Awakening,” Survival 50, No. 2 (March 2008): 67-94. This amounted more to a strategy of appeasement or state-breaking than state-building. Rather than provide the state with a monopoly on the use of force, as counterinsurgency theory suggests, the United States was helping pacify its enemies by letting them set up mini-states. The Kurds in Iraq got a similar deal when the U.S. took over. And lots of other insurgents, or groups opposed to central rule, like those in Pakistan’s Northwest Frontier Province, were bought off with similar grants of autonomy.105Staniland, “States, Insurgents, and Wartime Political Orders.”

In Afghanistan, where power has always been decentralized, state attempts to assert authority can be a cause of conflict. The attempt to displace local power brokers—warlords, in the parlance of this war—on behalf of the authorities in a distant capital can turn the United States into a revolutionary power. The Afghan state too often reaches Afghans not through the provision of services but via predatory national police or abusive soldiers.106Nir Rosen, “How We Lost the War We Won: Rolling Stone’s 2008 Journey Into Taliban-Controlled Afghanistan,” Rolling Stone, January 31, 2011, https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-news/how-we-lost-the-war-we-won-rolling-stones-2008-journey-into-taliban-controlled-afghanistan-181423/; Felbab-Brown, “How Predatory Crime and Corruption in Afghanistan Underpin the Taliban Insurgency.” Backing those forces can turn groups of people who had no conflict with the United States into enemies. Pockets of local authority may threaten the Afghan government without bothering U.S. interests, properly defined. The building of the state’s monopoly on violence, in other words, may require a lot of fighting that does not necessarily advance U.S. security aims. The idea that we can only leave Afghanistan once it is a centralized, peaceful country that collects taxes and provides services throughout its territory is a recipe to stay forever.

A second problem with Washington’s counterinsurgency doctrine for Afghanistan is it promotes dependence. It subverts the logic behind Charles Tilly’s dictum on state-building: “[W]ar made the state, and the state made war.”107Charles Tilly, “War Making and State Making as Organized Crime,” Bringing the State Back In, eds. Peter Evans, Dietrich Rueschemeyer, and Theda Skocpol (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985). In cases of powerful states supporting the state-building efforts of weak ones, the latter can be deformed by dependence on foreign aid, rather like a rentier state dependent on oil or some other state-controlled resource.108Barnett R. Rubin, “Everyone Want a Piece of Afghanistan,” Foreign Policy, March 11, 2019, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/03/11/everyone-wants-a-piece-of-afghanistan-russia-china-un-sco-pakistan-isi-qatar-saudi-uae-taliban-karzai-ghani-khalilzad-iran-india/. The fact that most economic output in Afghanistan results from aid and flows through Afghan elites is a recipe for massive corruption and debilitating cronyism. A constant supply of U.S. taxpayer funds undercuts the need for Afghanistan’s rulers to grow state revenue and develop a professional military. This is not to say no one will try, but reliable foreign assistance creates incentives that at least partially deform the state.

A third problem with the theory underlying the U.S. war in Afghanistan is the unavoidable limits on U.S. political will.109J. Baxter Oliphant, “After 17 Years of War in Afghanistan, More Say U.S. Has Failed than Succeeded in Achieving Its Goals,” Pew Research Center, October 5, 2018, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/10/05/after-17-years-of-war-in-afghanistan-more-say-u-s-has-failed-than-succeeded-in-achieving-its-goals/.

After the initial surge of fear and desire for justice in 2001, it has become increasingly evident that the fighting in Afghanistan has little impact on most Americans. Despite the substantial resources expended on Afghanistan, the war costs most Americans little. This make them less interested in the war and liable to actively oppose it.110Tanisha M. Fazal and Sarah Kreps, “The U.S.’ Perpetual War in Afghanistan,” Foreign Affairs, August 20, 2018, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/north-america/2018-08-20/united-states-perpetual-war-afghanistan. Furthermore, the limited consequences of success or failure mean public support for the war will not withstand higher costs.

The low public tolerance for this war means the United States is not likely to make the sort of massive commitment to policing and state building in Afghanistan the counterinsurgency doctrine really calls for—at least 100,000 troops for years on end and a much more coercive war that offends liberal values.111James T. Quinlivan, “Force Requirements in Stability Operations,” RAND, 1996, https://www.rand.org/pubs/reprints/RP479.html. This lack of U.S. will is evident to the Taliban, who are thereby encouraged to be patient. Arguably, then, the U.S. effort encourages the enemy even as it infantilizes our main ally.

Prospects for settlement

U.S. exit from Afghanistan should not be contingent on the successful conclusion of peace talks with the Taliban or the end of Afghanistan’s civil war. Recent U.S.-Taliban talks seem to have produced a deal to remove 5,000 or 6,000 U.S. troops in exchange for a Taliban ceasefire with Afghan forces, denunciation of Al-Qaeda, and scheduled talks with the Afghan government.112Dan Lamothe, John Hudson, and Pamela Constable, “U.S. preparing to Withdraw Thousands of Troops from Afghanistan in Initial Deal with Taliban,” Washington Post, August 1 ,2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/us-preparing-to-withdraw-thousands-of-troops-from-afghanistan-in-initial-deal-with-taliban/2019/08/01/01e97126-b3ac-11e9-8f6c-7828e68cb15f_story.html. Though this would only reduce U.S. force levels to where they were at the start of the Trump administration, the deal could be a useful step towards ending U.S. involvement in the war or even achieving a sustainable status quo in Afghanistan once Taliban negotiations with Kabul commence.

The danger is that negotiations could keep U.S. troops in Afghanistan rather than facilitating their departure. Because the Taliban’s main demand in negotiations is the removal of U.S. forces, U.S. leverage comes largely from withholding their withdrawal. That means even successful talks may prolong a war overdue to end. Should the Taliban fail to comply with their end of the deal, U.S. officials may delay scheduled withdrawal or settle for a mere draw down.

The United States should not wait on Taliban actions to leave Afghanistan. The Taliban will give little in negotiations that they will not give anyway. True, there is value in getting the Taliban to formally commit to denying haven to Al-Qaeda, ISIS, and other terrorists intending foreign attacks. But, as noted, the major reason for the Taliban to make that commitment is their own self-interest in not being attacked, which operates with or without an agreement. Nor it is obvious that the Taliban, given its decentralization, has leaders that can reliably bind all Taliban commanders to any deal they strike.113Antonio Giustozzi, “Negotiating with the Taliban: Issues and Prospects,” Century Foundation (2010), https://tcf.org/assets/downloads/tcf-Giustozzi.pdf. And while the United States has probably influenced the timing of Taliban talks with the Afghan government, it is unclear that U.S. pressure will much affect their position in those talks. Indeed, there is reason to think that U.S. departure could accelerate the eventual settlement of the Afghan civil war.

What Afghanistan really needs is a peace deal, which is mostly dependent on the Afghan parties. U.S. withdrawal should ultimately aid that purpose, though not necessarily on terms favorable to the government in Kabul. There is no question a U.S. military pullout would damage the Afghan government’s military prospects against the Taliban in the near term. Those who argue U.S. withdrawal will add to the Taliban’s eagerness to go on the offensive and take as much territory as possible, perhaps precipitating the government’s collapse, may be proven right.114Pamela Constable, “Afghan Government Puts Brave Face on U.S. Withdrawal, But Experts Are Alarmed,” Washington Post, December 21, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/afghan-government-puts-brave-face-on-us-withdrawal-but-experts-alarmed/2018/12/21/6f17dc94-0504-11e9-9122-82e98f91ee6f_story.html. Still, that take may oversimplify Taliban aims and overstate its relative capability.

As long as U.S. forces have been in Afghanistan, the Taliban has been focused on their removal. Understanding that U.S. will to fight is limited and time is on their side, the Taliban have had incentive to inflict harm, wait, and offer little toward political compromise. If U.S. forces leave, the balance of power between rival Afghan forces will clarify, and the sides’ aims may turn out to be more compatible than anticipated. The lack of a foreign occupier should exacerbate intra-Taliban divisions, including disagreement about whether to continue efforts to rule all of Afghanistan. Taliban knowledge that trying to consolidate rule over Hazaras, Tajiks, Uzbeks, and other non-Pashtuns will likely mean perpetual war should encourage compromise.

An intra-Afghan settlement would probably require the government to accept power-sharing with the Taliban and limited authority in districts where Taliban leaders are powerful. It would free the Afghan military to focus on ISIS-K, other terrorists, and renegade Taliban factions. Even if the Taliban does agree to a peace deal, it is unlikely to include all its fighters—some commanders and perhaps the whole Haqqani network may hold out, and the Taliban might join the government in attacking them.

Making Afghanistan someone else’s problem

The United States should force proximate powers to take more responsibility for Afghanistan. Their involvement is inevitable, as porous borders and poverty mean Afghanistan’s more powerful neighbors will retain considerable influence over its politics. One cannot assume U.S. departure will make all regional players cooperate toward a settlement of Afghanistan’s troubles, but there are indications a U.S. pullout will enhance their willingness to pursue more stabilizing policies there.115Barry R. Posen, “It’s Time to Make Afghanistan Someone Else’s Problem,” The Atlantic, August 18, 2017, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2017/08/solution-afghanistan-withdrawal-iran-russia-pakistan-trump/537252/. Heavy U.S. involvement may stymie nearby powers’ ability to engage in the political bargaining that could resolve the proxy conflicts which help fuel Afghanistan’s troubles.

Advocates of keeping U.S. troops in Afghanistan argue frequently that withdrawal would foment “instability” in the region, especially in neighboring Pakistan. That claim lacks merit given that U.S. forces have never pacified Afghanistan. Pakistan and other neighbors are experiencing the negative consequences of civil war already. At the same time, U.S. forces in Afghanistan likely enhance destabilizing fears and resentment from Pakistan and Iran, which has had U.S. troops stationed on either side of it since 2003. Moreover, to the extent U.S. efforts to aid Afghanistan’s government and suppress insurgents do serve regional powers’ interests, those countries are free-riding on U.S. efforts. Other nations, especially U.S. rivals, should be encouraged to protect their own interests in Afghanistan.

Proponents of staying in Afghanistan say U.S. adversaries will fill the “vacuum” left by U.S. forces and somehow benefit as a result. But getting rivals to do more to police civil conflicts in their own region is a benefit of leaving for the United States, not a cost. Afghanistan is too poor and divided to offer occupying powers a way to enhance their own power.116Stephen Van Evera, “Why Europe Matters, Why the Third World Doesn’t: American Grand Strategy after the Cold War,” Journal of Strategic Studies 13, no. 2 (June 1990): 1–51. Afghanistan offers no great industry to capture; limited natural resources to extract; and plenty of expensive, complex problems to manage. Both the Soviet and U.S. experiences, in fact, prove occupying Afghanistan is a drain on power. It would be a victory for the United States if a rival foolishly assumed the burden of pacifying Afghanistan.

Pakistan has always been the Taliban’s main sponsor. Its abiding interest in Afghanistan results from an intertwined history, a disputed border, and a somewhat convoluted idea about providing “strategic depth” in a war against India.117C. Christine Fair, Fighting to the End: The Pakistan Army’s Way of War (New York, Oxford University Press), 103–135. These factors suggest Pakistan will continue to play a destabilizing role in Afghanistan and sponsor the Taliban. On the other hand, Pakistani leaders reportedly recently agreed, under economic duress, to a deal where they received financial assistance from Gulf States on the condition they stopped blocking Taliban entry into peace talks.118Rubin, “Everyone Want a Piece of Afghanistan.” Some Pakistani leaders likely worry about the blowback of extremism from Afghanistan spreading into western Pakistan.119Rabia Akhtar and Jayita Sarkar, “Pakistan, India, and China after The U.S. Drawdown from Afghanistan,” Stimson Center (January 2015), https://www.stimson.org/sites/default/files/file-attachments/pakistan-india-china-after-us-afghanistan.pdf. Insofar as the Taliban retains influence in Afghanistan and Indian involvement is limited, Pakistani hardliners in the ISI and beyond may feel they have secured their essential aims in Afghanistan. For these reasons, Pakistan may support a peace deal among Afghan parties.

The other powers near Afghanistan have clearer interests in working toward its stability and supporting Kabul’s potential agreement with the Taliban. India, already the largest regional donor to Afghanistan, primarily wants to limit the use of Afghanistan as a base for jihadi militants who foment separatism in Kashmir and to increase investment opportunities.120Rubin, “Everyone Want a Piece of Afghanistan.” Indian interests may be satisfied by a deal whereby the Taliban agree to exclude international terrorist operations. India’s ambitions to increase trade with Afghanistan are also served by peace.

China has similar interests, which explains why it has joined Russia and India in pushing the Afghan peace process, despite resistance from Pakistan, its longtime near-ally.121Ibid. China’s nebulous “Belt and Road Initiative”—primarily a pile of centrally-planned infrastructure loans in South and Southeast Asia—is a reason to limit unrest in Afghanistan and Pakistan.122Andrew Chatzky and James McBride, “China’s Massive Belt and Road Initiative,” Council on Foreign Relations, May 21, 2019, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/chinas-massive-belt-and-road-initiative. Beijing’s desire to repress Muslim separatists is also a reason to aid the Afghan government’s policing capability.

Iran is likewise a natural adversary of the Taliban (and ally of the Afghan government) due to its ties to Afghan Shi’ites, whom the Taliban previously repressed. Iran nearly went to war with the Taliban in 1998, but conflict with the United States has shifted that calculus. Iran’s leaders accuse Saudi and Emirati intelligence operatives of using Afghanistan as a base to launch terror attack on Iran and allege that Americans have used it as a surveillance base.123Rubin, “Everyone Want a Piece of Afghanistan.” For these and other reasons, Iran has opened up diplomatic channels to the Taliban and, by some accounts, given them aid.124Ibid; Aziz Amin Ahmadzai, “Iran’s Support for the Taliban Brings It to a Crossroads with Afghanistan,” The Diplomat, May 21, 2018, https://thediplomat.com/2018/05/irans-support-for-the-taliban-brings-it-to-a-crossroads-with-afghanistan/. On the 1990s, Douglas Jehl, “Iran Holds Taliban Responsible for 9 Diplomats’ Deaths,” New York Times, September 11, 1998, https://www.nytimes.com/1998/09/11/world/iran-holds-taliban-responsible-for-9-diplomats-deaths.html. Iran’s differences with Afghanistan’s government seem likely to be resolved after a U.S. departure. Without a U.S. military presence, Tehran would likely resume its traditional efforts to stabilize its border.