Key points

- Some U.S. leaders fear that reducing U.S. military presence in the Middle East, or removing U.S. forces from warzones, will leave “vacuums,” which adversaries, especially Russia or China, will fill. These fears imagine a precarious balance of power where minor gains by U.S. adversaries create grave dangers—in reality, U.S. security is so profound that almost any potential vacuums are immaterial.

- Historically, there were various reasons to care about rivals gaining control of foreign territory, but technological change, especially nuclear weapons, and changes in how countries generate wealth means few of these reasons apply today for the United States.

- In any case, if U.S. forces leave a war zone or end an occupation, the beneficiaries who enjoy greater influence are likely to be local governments, not other distant powers.

- Today, the places U.S. troops are sent to stabilize tend to be strategically unimportant or irrelevant—that is, not valuable territory for any outsider to control. Therefore, foreign efforts to exploit any potential vacuum created by a U.S. exit will not harm U.S. security.

- As for wealthier places, like the oil-producing Gulf States, U.S. military exit will not create a vacuum. Influence is not obviously lost by removing troops, foreign powers will not rush to replace U.S. forces, and if they did, it would be a burden, not a boon.

“We will not walk away and leave a vacuum to be filled by China, Russia, or Iran,” President Biden said this July in defense of his administration’s continued commitment to the Middle East.1“Biden Says the U.S. ‘Will Not Walk Away’ from the Middle East,” NPR, July 16, 2022, https://www.npr.org/2022/07/16/1111863983/biden-meets-gulf-leaders-strategy. His comments reflect a widely held misconception: that a U.S. military exit from the Middle East would empower U.S. adversaries, and thus somehow make Americans less secure.2Similar sentiments have been expressed by Gen. Frank McKenzie, head of US Central Command, Barbara Leaf, Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs, and a variety of defense analysts. See respectively, Joseph Choi, “Top General: Russia, China Will Look to Expand Influence in Middle East as U.S. Pulls Back,” The Hill, May 23, 2021, https://thehill.com/policy/international/middle-east-north-africa/554994-top-general-russia-china-will-look-to-expand/; “Senate Hearing on China’s Presence in the Middle East,” C-SPAN, August 4, 2022; Seth Cropsey and Gary Roughead, “A U.S. Withdrawal Will Cause a Power Struggle in the Middle East,” Foreign Policy, December 17, 2019, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/12/17/us-withdrawal-power-struggle-middle-east-china-russia-iran/. U.S. leaders and pundits have expressed similar fears about the danger of creating vacuums by leaving Syria, Afghanistan (before U.S. exit of course), and even Africa, where only smatterings of U.S. troops are stationed.3On Syria, see Joe Concha, “Bret Stephens: Pulling U.S. Troops from Syria Will Create a Vacuum,” The Hill, December 28, 2018, https://thehill.com/homenews/media/423085-bret-stephens-pulling-us-troops-in-syria-will-create-a-vacuum/; Remarks of James Jeffrey at the Atlantic Council, “The Future of U.S. Policy in Syria,” December 17, 2018, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/event/the-future-of-us-policy-in-syria-event-recap/. On Afghanistan, see Ron Synovitz, “Regional Powers Seek to Fill Vacuum Left by West’s Retreat From Afghanistan,” Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty, December 25, 2021, https://www.rferl.org/a/afghanistan-power-vacuum-russia-iran-china-pakistan/31624955.html; Robble Gramer and Jack Detsch, “Foreign Powers Jockey for Influence in Afghanistan After Withdrawal,” Foreign Policy, June 24, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/06/24/afghanistan-withdrawal-foreign-power-vacuum/; Peter Aitken, “China, Russia Can and Will Exploit Opportunities in Afghanistan Vacuum Following U.S. Withdrawal: Experts,” Fox News, August 26, 2022, https://www.foxnews.com/world/china-russia-can-will-exploit-opportunities-afghanistan-vacuum-following-us-withdrawal-experts; On Africa see Ryan CK Hess, “Counterbalancing Chinese Influence in the Horn of Africa: A Strategy for Security and Stability,” Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs, November 18, 2021, https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/JIPA/Display/Article/2847035/counterbalancing-chinese-influence-in-the-horn-of-africa-a-strategy-for-securit/; Dylan Yachyshen, “Great Power Competition and the Scramble for Africa,” Foreign Policy Research Institute, April 30, 2020, https://www.fpri.org/article/2020/04/great-power-competition-and-the-scramble-for-africa/; Steve Holland and Lesley Wroughton, “U.S. to Counter China, Russia Influence in Africa: Bolton,” Reuters, December 13, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-trump-africa/u-s-to-counter-china-russia-influence-in-africa-bolton-idUSKBN1OC1XV. On global vacuums, see “Will China Fill the Vacuum Left by America?,” The Economist, June 8, 2017, https://www.economist.com/china/2017/06/08/will-china-fill-the-vacuum-left-by-america; Howard W. French, “While America Slept, China Became Indispensable,” Foreign Policy, May 9, 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/05/09/us-china-competition-africa-central-asia-infrastructure-development/; David E. Sanger and Jane Perlez, “Trump Hands the Chinese a Gift: The Chance for Global Leadership,” New York Times, June 1, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/01/us/politics/climate-accord-trump-china-global-leadership.html. Vacuum fears also fuel more general warnings against surrendering influence in the developing world. Chinese investments via its Belt and Road Initiative—a massive set of infrastructure-development loans—for example, are said to exploit a vacuum the United States should compete to fill. Chinese trade in South America, or Russian port calls there, are said to reflect a failure to exert U.S. influence.4Said to be worth more than $1 trillion, BRI’s ambitions have been scaled back. On the initial ambitions see, Jane Perlez and Yufan Huang, “Behind China’s $1 Trillion Plan to Shake Up the Economic Order,” New York Times, May 13, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/13/business/china-railway-one-belt-one-road-1-trillion-plan.html. On the reduced ambition, see, Lingling Wei, “China Reigns in Its Belt and Road Program, $1 Trillion Later,” Wall Street Journal, September 26, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-belt-road-debt-11663961638.

The burgeoning idea behind these claims is that “great power competition,” which once seemed a useful rationale for exiting conflicts and lingering endeavors of the global war on terror, demands winning an open-ended, ill-defined contest for influence with Russia and China in the greater Middle East and developing world, or what is now sometimes called the global south.5On great power competition as a rival to counterterrorism wars, see Ronald O’Rourke, “Great Power Competition: Implications for Defense—Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service, November 8, 2022, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/natsec/R43838.pdf. Vacuums that could be said to follow a U.S. exit—not the terrorists or insurgents U.S. forces were deployed to fight—are the new justification for staying.

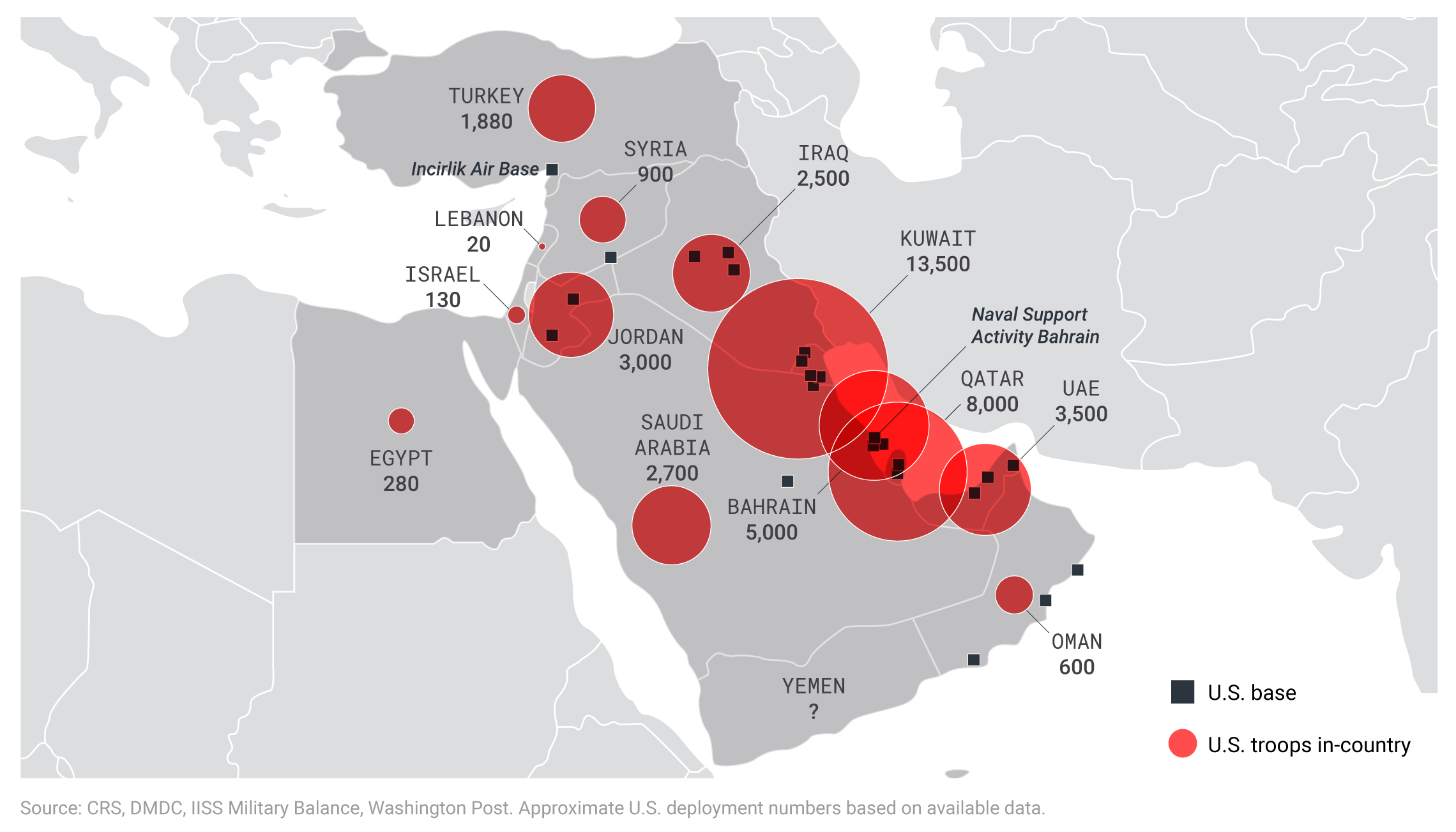

U.S. bases and troop levels in the Middle East

The U.S. military’s outsized basing presence in the Middle East is often justified by fears that a withdrawal from the region will leave vacuums for Russia and China to fill. This threat of dangerous vacuums is largely a myth.

Vacuum arguments are wrong in several ways. First, they falsely assume that if U.S. forces leave some territory, the beneficiary of the resulting vacuum—a sudden shift in political power away from central or occupying authority—will be other distant powers, not local governments. Second, vacuum fears overestimate rival powers’ capacity to gain something from filling in for U.S. forces in war-torn countries—they see gifts to Russia or China in what are generally burdens. Third, they overstate the degree to which the U.S. loses influence by removing troops from regions, like the Middle East, and China or Russia’s desire or ability to replace them. Finally, vacuum claims wrongly see U.S. security as so precarious—the global balance of power so shaky—that potential (but unlikely) minor gains for adversaries meaningfully damage U.S security.

What territory matters to security

To understand why vacuum fears are so wrong, it is useful to first consider how territory outside a state’s borders can affect its security. Doing so reveals how little foreign territory matters today for U.S. security. Even adversaries gaining influence over wealthy countries would not necessarily impact U.S. security. Who holds sway over the war-torn and poor states where U.S. forces fight and assume occupational duties matters far less.

There a variety of ways, sketched here, that foreign territory may matter to a state’s security such that it might want to control it or at least deny it to a rival. Several caveats are in order. First, these are not all the reasons states care about foreign territory—these are the security reasons. So imperial desires, desire to unite people who believe they share a nationality, and pure plunder are not on the list. Second, states frequently propagandize about this sort of thing, shrouding imperial motives with security arguments and vice versa, and leaders in particular states have competing motives for the same action, so history is not as straightforward as the theory. Third, the fact that a state has some good reason to want to control some territory does not itself establish that it is a good idea to do so. Nationalistic resistance to occupation can make conquest pyrrhic.

Direct avenue for attack

The obvious reason to worry about a rival controlling some territory is if it offers an avenue for direct attack. Access to a bordering state is a prerequisite for ground invasion, which is essential to take and hold territory. A nearby territory, including some islands, can provide a logistics center to mount air raids or amphibious attacks, as occurred with the U.S. island-hopping campaign in the Pacific during World War II.6For example, Taiwan is arguably important to Chinese leaders not just because they view it as part of their country, but because its proximity to their coast means it could be used as base to attack the mainland. Mike Sweeney, “How Militarily Useful Would Taiwan be to China?,” Defense Priorities, April 12, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/how-militarily-useful-would-taiwan-be-to-china.

This logic can be extended to overseas territories. For example, in the nineteenth century’s “great game,” Great Britain worried about Afghanistan as an arena for a Russian threat to its colony India.7Moonis Ahmar, “Review: The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia by Peter Hopkirk,” Strategic Studies 16, no. 4 (Summer 1994): 90-95. Colonies are gone today, but the United States’ far-flung garrisons and allies can generate colonial-style fears about peripheral territory.

It is easy to see how applying this logic can create self-perpetuating insecurity, an expanding frontier of worries, as leaders worry about territory peripheral to their occupied territory or garrison and then territory peripheral to that. Such fears can enable imperial expansion, or at least expanded meddling. That is especially pernicious given that states, as Adam Smith long ago noted, often overvalue having direct political control over foreign markets with which they could overwise still trade.8Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations (Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 1976). There may be a psychological “endowment effect” at play, such that states grow attached and overvalue overseas colonies and bases compared with unpossessed territory.9Daniel Kahneman, Jack L. Knetsch, and Richard H. Thaler, “Anomalies: The Endowment Effect, Loss Aversion, and Status Quo Bias,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 5, no. 1 (Winter 1991): 193-206. So states can spend more and more to protect something that is not worth much to begin with.

Also, if a state has enough defensive or deterrent capability (whether it comes via conventional capability or, more cheaply, by nuclear weapons), it need not worry so much about nearby territory being controlled by rivals.10Robert Jervis, “Cooperation Under the Security Dilemma,” World Politics 30, no. 2 (Jan 1978): 167-214. Thus one can argue that the U.S. reaction to the prospect of Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba in 1962 was overwrought. It did not prevent assured U.S. nuclear retaliation in the event of a Soviet attack, so deterrence remained firm.

Exploitable value

Another reason territory might matter is its exploitable value—its potential to yield cumulative gains that could make an occupying enemy more threatening.11Peter Liberman, Does Conquest Pay?: The Exploitation of Occupied Industrial Societies (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988); Steven Pinker, The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (New York, Penguin Books, 2012). This value comes via raw materials, like oil or metals, or in industry that can be controlled and reaped for profit that add to the conqueror’s wealth, military capacity, and ability to threaten further territory. Note, however, that gaining military control over production does not necessarily make it easily exploitable for profit since administration may be difficult, workers may quit, and the cost of control can swamp benefits given armed resistance.

In advanced economies, less wealth is now tied up in industrial production and extraction and more in knowledge, making conquest a less attractive or profitable prospect.12Carl Kaysen, “Review: Is War Obsolete?: A Review Essay,” International Security 14, no. 4 (Spring 1990): 42-64. This is arguably a major cause of interstate peace.13On this a phenomenon, see Shirin Sinnar and Doyle Hodges, “Race and National Security,” War on the Rocks, July 10, 2020, https://warontherocks.com/2021/07/war-is-on-the-rocks/; Pinker, The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined Hence, while one can imagine a state trying to exploit the intellectual property of companies in occupied territory for economic gain, the difficulties of extracting knowledge by force appear formidable, which is perhaps why this possibility remains hypothetical.14For example, see the discussion of China’s trying to conquer Taiwan to extract expertise about advanced semi-conductor production in Chris McCallion, “Semiconductors are not a Reason to Defend Taiwan,” Defense Priorities, October 5, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/semiconductors-are-not-a-reason-to-defend-taiwan.

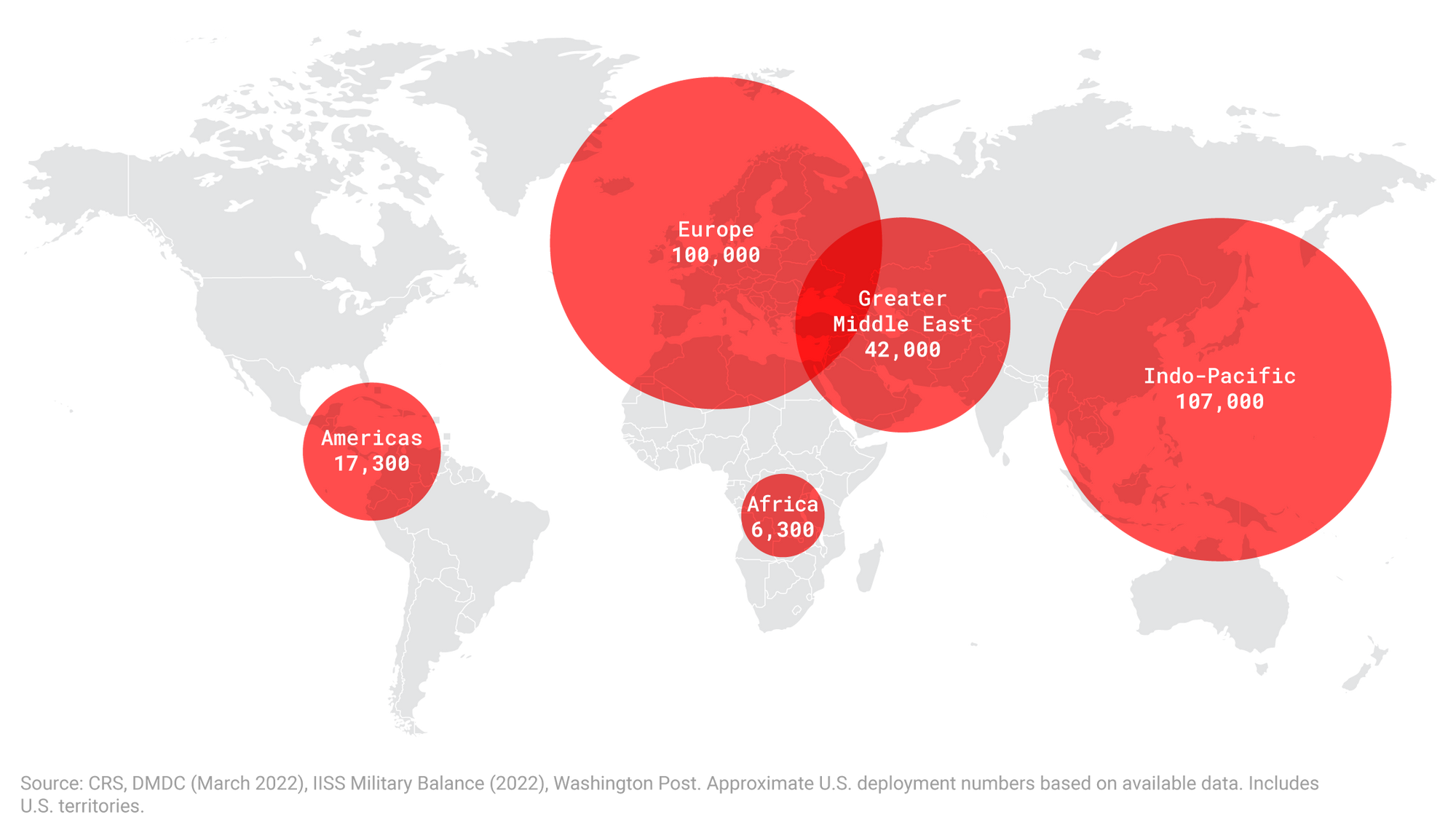

U.S. military and DoD personnel deployed overseas

The United States’ global constellation of military bases often create a self-perpetuating insecurity. Especially in the Middle East, the United States is in danger of spending more and more to protect something that is not worth much to begin with.

This balancing logic is how early twentieth century realist strategists argued for a U.S. military commitment to Europe.15Nicholas J. Spykman, America’s Strategy in World Politics: The United States and The Balance of Power (New York, Routledge, 2007); Walter Lippmann, The Cold War: A Study in U.S. Foreign Policy (New York, Harper, 1947). The danger was not just that a threatening state might add to its power by conquest, but also that it might become a regional hegemon, a state that conquered enough of Europe to threaten the United States—either with direct attack or economic ruin brought on by a closure of trade and becoming a garrison state through defensive militarization. In the Cold War, realist thought extended this thinking to East Asia, as it became a center of global wealth, and to the Middle East, due it its oil production. Some worried, rather implausibly, about Soviet conquest of oil-producing nations adding to its threat to the West.16Melvyn P. Leffler, “From the Truman Doctrine to the Carter Doctrine: Lessons and Dilemmas of the Cold War,” Diplomatic History 7, no. 4 (Fall 1983): 245-266. Others worried about a Middle Eastern state, like Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, gaining control of enough oil that it could control prices to harm the United States economically or coerce it by threatening production cuts.17Robert J. Lieber, “Oil and Power after the Gulf War,” International Security, 17. No. 1 (Summer, 1992): 155-176

Trade closure

A third major historical reason to worry about conquest is trade closure, either of conquered territory or shipping routes. By conquest of sufficient territory, a state could prevent a major chunk of the world from consuming rivals’ products and exporting material there. Nazi Germany’s conquests are an example, as was the case to an extent with the Soviet Union (which, keep in mind, was an empire in Eurasia), especially in the early Cold War.18“American Soviet Trade,” CQ Researcher, https://library.cqpress.com/cqresearcher/document.php?id=cqresrre1959090200.

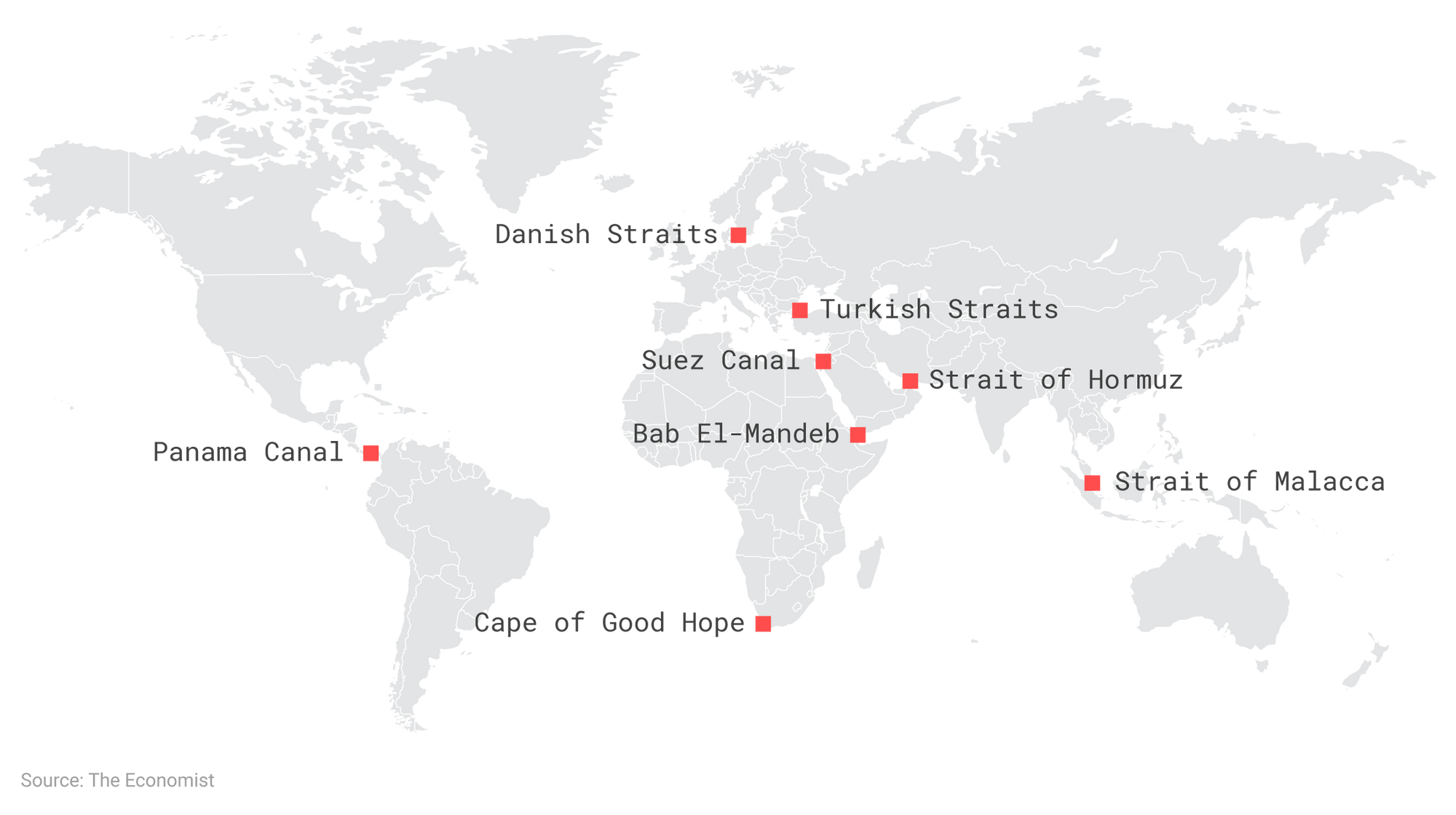

Foreign territory might also matter to security if can be used to molest key trade routes. Since most trade routes can change to avoid troubled waters, and buyers can usually find a new supply base, the territory vital to trade is essentially several major straits, and the major canals.19Eugene Gholz and Daryl G. Press, “The Effects of Wars on Neutral Countries: Why it Doesn’t Pay to Preserve Peace,” Security Studies 10, no 4. (Summer 2001): 1-57. But note that this logic about shipping is easily abused: a broad definition of what “vital” trade routes are, and enough imagination about what threatens them, can make just about any territory seem key to trade.20Benjamin H. Friedman, “Bad Idea: Assuming Trade Depends on the Navy,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, January 7, 2022, https://defense360.csis.org/bad-idea-assuming-trade-depends-on-the-navy/.

Does any foreign territory still matter to the United States?

These theoretical reasons to worry about foreign territory apply poorly to most great powers today, especially the United States. Two vast oceans always offered great protection from invasion or even aerial attack. Modern military technologies—radar tied to accurate missiles, artillery, mines, and more—further advantage defenders of borders and especially coastlines.21Barry R. Posen, ”Command of the Commons: The Military Foundation of U.S. Hegemony.” International Security 28, no. 1. (Summer 2003): 5-46. Adjacent territory and nearby territory thus poses less potential threat. Even before nuclear weapons, modern militaries elevated the cost of conquest substantially. Whether or not conquest ever reliably paid, it pays less today than it once did. This is another reason for the dramatic decline of interstate warfare since World War II, as economist Carl Kaysen explained decades ago.22Kaysen, “Review: Is War Obsolete?: A Review Essay.”

Today, the United States must no longer worry about attacks coming from Canada, Mexico, or other nearby territories. This is both because those countries are stable and secure and because nuclear weapons render the issue of invasion almost moot.23Robert Jervis, The Meaning of the Nuclear Revolution: Statecraft and the Prospect of Armageddon (New York, Cornell University Press, 1990). A Russian base in Venezuela or even Cuba might give offense, but it would not open the way for the Russians to invade or coerce the United States.

And even if one can work up concern about how a rival might use European, Asian, or Middle Eastern wealth to attack or isolate the United States, it is difficult to imagine any power capable of conquering enough of those areas to matter much. Other big powers, most of them U.S. allies, are capable of balancing Russia and China in Europe and Asia—in the sense of preventing them from becoming regional hegemons by conquest.24Eugene Gholz, Daryl G. Press, and Harvey M. Sapolsky, “Come Home, America: The Strategy of Restraint in the Face of Temptation,” International Security 21, no. 4 (Spring 1997): 5-48. China, with an economy that may soon overtake the United States in total size, is certainly growing more powerful, but mountains and oceans with capable militaries across them, and nuclear neighbors Russia and India, hem it in. East Asia, as political scientist Robert Ross says, has as “geography of peace,” because it is defense dominant.25Robert S. Ross, “The Geography of the Peace: East Asia in the Twenty-First Century,” International Security 23, no. 4 (Spring 1999): 81-118.

It is harder today to extract wealth from conquest than it was a century ago, and it was not easy then. Value in modern advanced economies is less in physical plants that one can loot or easily control than in human knowledge that requires broad cooperation, which is hard to gain by force. Nationalism also makes conquest more difficult. People are prone to resist occupation and make it unprofitable, as Ukraine has recently demonstrated. Even if China, for example, conquered Taiwan, it would struggle to gain more from directly controlling it than it does from trading with it. And resistance might make the cost of control not just expensive, but also a burden that checks ambitions for further attempts at expansion. Generally speaking, bids at empire would be bad for U.S. rivals.26George F. Kennan, “The Sources of Soviet Conduct,” Foreign Affairs 25, no.4 (July 1947): 566-582, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russian-federation/1947-07-01/sources-soviet-conduct.

Territory vital to trade is quite limited, given modern markets. Globalization creates supply options, limiting the need to police trade.27Harvey M. Sapolsky, Benjamin H. Friedman, Eugene Gholz, and Daryl G. Press, “Restraining Order: For Strategic Modesty,” World Affairs 172, no. 2 (Fall 2009): 84-94. With some disruption and perhaps some added price, almost all goods can be produced in other places. There are important chokepoints to global trade, like the Strait of Hormuz. But these can likely be kept open by capable naval forces without having to control nearby territory. Other chokepoints, like Strait of Malacca or Suez Canal, can be bypassed for added cost, as we saw recently when the Ever Given cargo ship temporarily blocked the canal, creating disruptive cost, not a halt to global trade.28George Griffiths and David Lademan, “Container Ships Turn to Cape of Good Hope as Suez Issues Continue: cFlow,”

S&P Global Commodity Insights, March 25, 2021, https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/shipping/032521-container-ships-turn-to-cape-of-good-hope-as-suez-issues-continue-cflow.

Oil is special because, as a global commodity, there is one price, and control of enough production allows a state to move prices through shifts in output. A substantial enough price spike could cause a U.S. recession. But suppliers tend to depend on buyers enough to keep the oil flowing, making most worries about supply cutoffs being used as blackmail overwrought.29Eugene Gholz and Daryl G. Press, “The Effects of Wars on Neutral Countries: Why it Doesn’t Pay to Preserve Peace,” Security Studies 10, no 4. (Summer 2001): 1-57. And, as a small economic literature explains, the U.S. has added capacity to withstand price spikes due to domestic production, reserves, and wealth creation that makes energy prices less important economically.30Olivier J. Blanchard and Marianna Riggi, “Why are the 2000s so Different from the 1970s? A Structural Interpretation of Changes in the Macroeconomic Effects of Oil Prices,” Journal of the European Economic Association 11, no. 5 (August 2013): 1032-1052. In any case, military power in the Middle East is so divided among rival states that a single state gaining control of most of the region’s oil production is nearly unthinkable.31Justin Logan, “The Case for Withdrawing from the Middle East,” Defense Priorities, September 30, 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/the-case-for-withdrawing-from-the-middle-east.

Main global oil shipping chokepoints

U.S. bases should not be maintained in the name of safeguarding shipping. Naval forces can keep sea lanes open without the cost and risks of controlling territory.

U.S. overseas bases likewise are rarely so vital that it would be worth occupying a country just to protect them. Japan, which could be vital in the event the United States elected to defend Taiwan against China, is more the exception than the rule. Naval forces and other land bases would likely replace the base at less cost than the occupation. So, the U.S. is not in a situation like Great Britain thought it was with its Indian Colony, unless we define their trouble there not as an actual threat from Russia in Afghanistan, but a tendency to overvalue the colony and overrate threats to it, such that it fought needless wars to protect it.

In sum, because of geography, wealth, military might (especially nuclear weapons), and the ability of other states to balance the power of rivals, the United States does not have to worry about territory as it used to—even in the richest parts of the world. One can come up with a lot of reasons why China or Russia controlling more wealthy territory might “matter” to Americans, but it would take a massive shift in capability to matter in a way that meaningfully diminishes U.S. security. The mental models that tell us to worry about such developments are from other times and places when security was scarce, the balance of power was easily changed, and the occupied territory far more useful.

Rival control of territory in the developing world matters even less to U.S. security. This does not mean Americans are forever done with sensibly worrying about conquest or foreign occupations—but it does mean they can afford to worry a lot less, while keeping an eye on the balance of power.

Vacuums benefit local actors, not other great powers

“Nature abhors a vacuum.” This idea, popularized by Aristotle, underlies fears about leaving vacuums for rivals to fill. But it should not be assumed that every military occupation that leaves is a vacuum waiting to happen. U.S. military deployments with only a small contingent of troops, like U.S. special operations forces in Niger, probably create little or no power in the sense of controlling local conditions.32Faith Karimi, “US has Hundreds of Troops in Niger. Here’s Why,” CNN, May 10, 2018, https://www.cnn.com/2018/05/10/politics/niger-american-troops-presence. That means their end will leave little or no power vacuum to fill. But in most cases, U.S. force will have some effect, create some power which will shift with their departure, so vacuum theory is not entirely wrong.

In most cases, the obvious beneficiary of the U.S. exit are local actors. The idea of a vacuum left behind often relies on the idea that U.S. forces operate in failed states where no authority exists. But in fact, truly failed states with no real local power structures are exceedingly rare.33Jennifer Keister, “The Illusion of Chaos: Why Ungoverned Spaces Aren’t Ungoverned, and Why That Matters,” Cato Institute, December 9, 2014, https://www.cato.org/policy-analysis/illusion-chaos-why-ungoverned-spaces-arent-ungoverned-why-matters. What we call failed states are generally civil wars, where there are competing power structures, not none. U.S. exit will shift the balance of power among these forces, not to foreign actors. In other words, any vacuum will be quickly filled by local actors, as occurred with the Taliban as the U.S. exited Afghanistan.

Past U.S. withdrawals from wars and military occupations, even during the Cold War, showed this. U.S. forces left various Latin American countries, the Philippines, and Vietnam without great power rivals rushing into the breach. Rather than becoming a Chinese pawn, Vietnam went to war with them in 1979. If U.S. forces left Iraq tomorrow, the big winners would be Iraqis. Iran might gain some influence, but it also might lose some of its Iraqi support, as it becomes itself seen as an outsider inferring rather than an aid to pushing U.S. forces out. In Syria, the primary beneficiary of a U.S. exit would be the government led by President Bashar al-Assad, which would likely gain control of the territory U.S. forces patrol in the east. Iran and especially Russia would gain more area in which to operate, but they might lose some influence with the Syrian government as it gets less dependent on them.34Benjamin H. Friedman and Justin Logan, “Disentangling from Syria’s Civil War,” Defense Priorities, May 29, 2019, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/disentangling-from-syrias-civil-war.

U.S. wars and occupations occur in largely irrelevant territory

The second problem with vacuum theory is it is mostly used to oppose the withdrawal of U.S. troops from poor countries largely useless for building or contesting geopolitical power. The situation has not fundamentally changed since the end of the Cold War, when political scientist Steven Van Evera explained the futility of superpower competition in the third world.35Stephen Van Evera, “Why Europe Matters, Why the Third World Doesn’t: American Grand Strategy After the Cold War,” Journal of Strategic Studies 13, no. 2 (1990): 1-51. The characteristics that make territory important, as discussed above, do not apply there. Likewise, rivals today advancing their influence in what we now call the developing world is generally irrelevant to U.S security.

The sorts of places U.S. troops go to war tend to be poor and fractious. It is difficult to imagine a country less attractive to would-be occupiers than Afghanistan, but Syria should not be far behind. Both nations are, tragically, home to violent divisions, profound economic need, and well-armed people motivated to resist what is seen as foreign occupation; less gifts to occupiers than civil war management burdens for occupiers. One might well care about rivals controlling such territory for humanitarian or other kinds of moral reasons, but not because rivals will marshal their resources to menace the United States.

Some may say the danger is less that China or Russia will militarily occupy territories that U.S. forces leave than they will gain power there through trade or sly diplomacy. But the U.S. does not surrender the opportunity to seek influence these ways by pulling its forces. And the idea that Chinese firms’ operations in developing countries follow some profound geopolitical logic deserves great skepticism. If they are reacting to marching orders from the state, they are likely to be making poor investments, not winning great influence.36Christopher Mott, “Don’t Fear China’s Belt and Road Initiative,” Global Politics and Strategy 62, no. 4 (July 2020): 47-55. In most cases, they are primarily seeking profit. If they succeed, U.S. firms can compete. That is not a security matter.

Rich states make poor vacuums

Vacuum fears are also wrong when applied to more wealthy areas, including the greater Middle East.37The Middle East is not rich as a region—it comprises just four percent of global wealth, but oil production creates quite concentrated wealth that is potentially a boon to those who control it, including potential conquerors. Logan, “The Case for Withdrawing from the Middle East.” There is little reason to expect that Russia or China would rush to replace U.S. military forces in Saudi Arabia or Bahrain should they be withdrawn. The first reason for this is the point already discussed: Local powers would fill any vacuum rather than invite in new powers. The Middle East includes several reasonably strong states—Turkey, Israel, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Iran—that form a rather stable interstate peace, even as competition occurs in weaker states, like Yemen and lately Syria. A U.S. exit would not create an imbalance of power that might compel some of these nations to turn for protection to a new outside power (and as discussed in the next section, it would not much impact U.S. security if they did).38David Blagden and Patrick Porter, “Desert Shield of the Republic? A Realist Case for Abandoning the Middle East,” Security Studies 30, no. 1 (February 2021): 5-48.

True, what President Biden and others mean when they worry about is a vacuum created by U.S. exit that benefits greater power rivals is often vaguer, arguably more about lost influence and trade than a new military power bestriding the region. That argument has different flaws.

For one, as the U.S. relationship to Saudi Arabia lately demonstrates, it is unclear the U.S. forces in the region buy a great deal of influence that would be at stake with exit. With fewer U.S. forces in the region, oil producers would have basically the same profit-seeking incentives they do now. In other words, there would be no vacuum, or if you like, no bigger vacuum than there already is.

Second, after a U.S. exit, China and Russia would have similar opportunities to pursue influence in the Middle East via trade as they do now. It is not as if they are kept out economically by U.S. forces. As a major oil producer, Russia seeks to influence production elsewhere by horse-trading with Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, not coercion with occupying forces or threat.39Andrew S. Weiss and Jasmine Alexander-Greene, “What’s Driving Russia’s Opportunistic Inroads with Saudi Arabia and the Gulf Arabs,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, October 5, 2022, https://carnegieendowment.org/2022/10/05/what-s-driving-russia-s-opportunistic-inroads-with-saudi-arabia-and-gulf-arabs-pub-88099. Despite U.S. forces in the region, China imports much of its energy from there.40The Middle East accounts for approximately 50% of China’s crude oil imports. Jeff Baron, “Country Analysis Executive Summary: China,” U.S. Energy Information Administration, August 8, 2022, https://www.eia.gov/international/analysis/country/CHN. Middle Eastern states might be more inclined to work with China lately due to the opportunities its wealth creates, but this is not related to U.S. military presence. If you think the U.S. is losing influence in the Middle East, vacuums are not the issue and more troops is not the answer.

The U.S. balance of power with China and Russia not precarious

The fourth and final flaw in the vacuum theory follows from the limits of great power competition. U.S. security is abundant, thanks to its economy, geography, military capability, and nuclear weapons, as discussed above. So even if it were true that a foreign rival, rather than local government, was the likely beneficiary of a power vacuum created by a U.S. withdrawal and that there was actually profit to be had by occupying it, it still wouldn’t much matter to U.S. security.

The balance of power between the United States and Russia or China is not meaningfully affected by small changes, like who controls Afghanistan or Syria. China handing out loans in South Asia or its firms buying mines or energy contracts in Africa might bother people for one reason or another, but it has no meaningful impact on U.S. security. People may have legitimate worries that people in poor countries will fall under the influence of Russia or China because of their illiberal politics, but that should not be confused with a security argument.

Even in states with large oil reserves, like Iraq, foreign powers will struggle to take over the profits of production and would likely energize heavier opposition by trying. For outside powers, the places vacuum theory says U.S. forces cannot safely leave tend be drains on resources, not a source of cumulative gains that enhance power. The United States is weaker from two decades of military interventions and post-war occupations in the Middle East; there is no good reason to expect Russia or China would fare better.

The idea we should prolong U.S. deployments in strategically unimportant countries to avoid vacuums and to compete for security with rival powers is backwards. It is unlikely that Russia or China will see occupying much of the Middle East or poor areas of the world as a good idea, but they will likely suffer for it if they do. If the United States is as desperate to compete with China as current rhetoric indicates, we should vacate our costly occupations and pray Beijing emulates Washington’s follies.

Endnotes

- 1“Biden Says the U.S. ‘Will Not Walk Away’ from the Middle East,” NPR, July 16, 2022, https://www.npr.org/2022/07/16/1111863983/biden-meets-gulf-leaders-strategy.

- 2Similar sentiments have been expressed by Gen. Frank McKenzie, head of US Central Command, Barbara Leaf, Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs, and a variety of defense analysts. See respectively, Joseph Choi, “Top General: Russia, China Will Look to Expand Influence in Middle East as U.S. Pulls Back,” The Hill, May 23, 2021, https://thehill.com/policy/international/middle-east-north-africa/554994-top-general-russia-china-will-look-to-expand/; “Senate Hearing on China’s Presence in the Middle East,” C-SPAN, August 4, 2022; Seth Cropsey and Gary Roughead, “A U.S. Withdrawal Will Cause a Power Struggle in the Middle East,” Foreign Policy, December 17, 2019, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/12/17/us-withdrawal-power-struggle-middle-east-china-russia-iran/.

- 3On Syria, see Joe Concha, “Bret Stephens: Pulling U.S. Troops from Syria Will Create a Vacuum,” The Hill, December 28, 2018, https://thehill.com/homenews/media/423085-bret-stephens-pulling-us-troops-in-syria-will-create-a-vacuum/; Remarks of James Jeffrey at the Atlantic Council, “The Future of U.S. Policy in Syria,” December 17, 2018, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/event/the-future-of-us-policy-in-syria-event-recap/. On Afghanistan, see Ron Synovitz, “Regional Powers Seek to Fill Vacuum Left by West’s Retreat From Afghanistan,” Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty, December 25, 2021, https://www.rferl.org/a/afghanistan-power-vacuum-russia-iran-china-pakistan/31624955.html; Robble Gramer and Jack Detsch, “Foreign Powers Jockey for Influence in Afghanistan After Withdrawal,” Foreign Policy, June 24, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/06/24/afghanistan-withdrawal-foreign-power-vacuum/; Peter Aitken, “China, Russia Can and Will Exploit Opportunities in Afghanistan Vacuum Following U.S. Withdrawal: Experts,” Fox News, August 26, 2022, https://www.foxnews.com/world/china-russia-can-will-exploit-opportunities-afghanistan-vacuum-following-us-withdrawal-experts; On Africa see Ryan CK Hess, “Counterbalancing Chinese Influence in the Horn of Africa: A Strategy for Security and Stability,” Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs, November 18, 2021, https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/JIPA/Display/Article/2847035/counterbalancing-chinese-influence-in-the-horn-of-africa-a-strategy-for-securit/; Dylan Yachyshen, “Great Power Competition and the Scramble for Africa,” Foreign Policy Research Institute, April 30, 2020, https://www.fpri.org/article/2020/04/great-power-competition-and-the-scramble-for-africa/; Steve Holland and Lesley Wroughton, “U.S. to Counter China, Russia Influence in Africa: Bolton,” Reuters, December 13, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-trump-africa/u-s-to-counter-china-russia-influence-in-africa-bolton-idUSKBN1OC1XV. On global vacuums, see “Will China Fill the Vacuum Left by America?,” The Economist, June 8, 2017, https://www.economist.com/china/2017/06/08/will-china-fill-the-vacuum-left-by-america; Howard W. French, “While America Slept, China Became Indispensable,” Foreign Policy, May 9, 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/05/09/us-china-competition-africa-central-asia-infrastructure-development/; David E. Sanger and Jane Perlez, “Trump Hands the Chinese a Gift: The Chance for Global Leadership,” New York Times, June 1, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/01/us/politics/climate-accord-trump-china-global-leadership.html.

- 4Said to be worth more than $1 trillion, BRI’s ambitions have been scaled back. On the initial ambitions see, Jane Perlez and Yufan Huang, “Behind China’s $1 Trillion Plan to Shake Up the Economic Order,” New York Times, May 13, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/13/business/china-railway-one-belt-one-road-1-trillion-plan.html. On the reduced ambition, see, Lingling Wei, “China Reigns in Its Belt and Road Program, $1 Trillion Later,” Wall Street Journal, September 26, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-belt-road-debt-11663961638.

- 5On great power competition as a rival to counterterrorism wars, see Ronald O’Rourke, “Great Power Competition: Implications for Defense—Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service, November 8, 2022, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/natsec/R43838.pdf.

- 6For example, Taiwan is arguably important to Chinese leaders not just because they view it as part of their country, but because its proximity to their coast means it could be used as base to attack the mainland. Mike Sweeney, “How Militarily Useful Would Taiwan be to China?,” Defense Priorities, April 12, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/how-militarily-useful-would-taiwan-be-to-china.

- 7Moonis Ahmar, “Review: The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia by Peter Hopkirk,” Strategic Studies 16, no. 4 (Summer 1994): 90-95.

- 8Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations (Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 1976).

- 9Daniel Kahneman, Jack L. Knetsch, and Richard H. Thaler, “Anomalies: The Endowment Effect, Loss Aversion, and Status Quo Bias,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 5, no. 1 (Winter 1991): 193-206.

- 10Robert Jervis, “Cooperation Under the Security Dilemma,” World Politics 30, no. 2 (Jan 1978): 167-214.

- 11Peter Liberman, Does Conquest Pay?: The Exploitation of Occupied Industrial Societies (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988); Steven Pinker, The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (New York, Penguin Books, 2012).

- 12Carl Kaysen, “Review: Is War Obsolete?: A Review Essay,” International Security 14, no. 4 (Spring 1990): 42-64.

- 13On this a phenomenon, see Shirin Sinnar and Doyle Hodges, “Race and National Security,” War on the Rocks, July 10, 2020, https://warontherocks.com/2021/07/war-is-on-the-rocks/; Pinker, The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

- 14For example, see the discussion of China’s trying to conquer Taiwan to extract expertise about advanced semi-conductor production in Chris McCallion, “Semiconductors are not a Reason to Defend Taiwan,” Defense Priorities, October 5, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/semiconductors-are-not-a-reason-to-defend-taiwan.

- 15Nicholas J. Spykman, America’s Strategy in World Politics: The United States and The Balance of Power (New York, Routledge, 2007); Walter Lippmann, The Cold War: A Study in U.S. Foreign Policy (New York, Harper, 1947).

- 16Melvyn P. Leffler, “From the Truman Doctrine to the Carter Doctrine: Lessons and Dilemmas of the Cold War,” Diplomatic History 7, no. 4 (Fall 1983): 245-266.

- 17Robert J. Lieber, “Oil and Power after the Gulf War,” International Security, 17. No. 1 (Summer, 1992): 155-176

- 18“American Soviet Trade,” CQ Researcher, https://library.cqpress.com/cqresearcher/document.php?id=cqresrre1959090200.

- 19Eugene Gholz and Daryl G. Press, “The Effects of Wars on Neutral Countries: Why it Doesn’t Pay to Preserve Peace,” Security Studies 10, no 4. (Summer 2001): 1-57.

- 20Benjamin H. Friedman, “Bad Idea: Assuming Trade Depends on the Navy,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, January 7, 2022, https://defense360.csis.org/bad-idea-assuming-trade-depends-on-the-navy/.

- 21Barry R. Posen, ”Command of the Commons: The Military Foundation of U.S. Hegemony.” International Security 28, no. 1. (Summer 2003): 5-46.

- 22Kaysen, “Review: Is War Obsolete?: A Review Essay.”

- 23Robert Jervis, The Meaning of the Nuclear Revolution: Statecraft and the Prospect of Armageddon (New York, Cornell University Press, 1990).

- 24Eugene Gholz, Daryl G. Press, and Harvey M. Sapolsky, “Come Home, America: The Strategy of Restraint in the Face of Temptation,” International Security 21, no. 4 (Spring 1997): 5-48.

- 25Robert S. Ross, “The Geography of the Peace: East Asia in the Twenty-First Century,” International Security 23, no. 4 (Spring 1999): 81-118.

- 26George F. Kennan, “The Sources of Soviet Conduct,” Foreign Affairs 25, no.4 (July 1947): 566-582, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russian-federation/1947-07-01/sources-soviet-conduct.

- 27Harvey M. Sapolsky, Benjamin H. Friedman, Eugene Gholz, and Daryl G. Press, “Restraining Order: For Strategic Modesty,” World Affairs 172, no. 2 (Fall 2009): 84-94.

- 28George Griffiths and David Lademan, “Container Ships Turn to Cape of Good Hope as Suez Issues Continue: cFlow,”

S&P Global Commodity Insights, March 25, 2021, https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/shipping/032521-container-ships-turn-to-cape-of-good-hope-as-suez-issues-continue-cflow. - 29Eugene Gholz and Daryl G. Press, “The Effects of Wars on Neutral Countries: Why it Doesn’t Pay to Preserve Peace,” Security Studies 10, no 4. (Summer 2001): 1-57.

- 30Olivier J. Blanchard and Marianna Riggi, “Why are the 2000s so Different from the 1970s? A Structural Interpretation of Changes in the Macroeconomic Effects of Oil Prices,” Journal of the European Economic Association 11, no. 5 (August 2013): 1032-1052.

- 31Justin Logan, “The Case for Withdrawing from the Middle East,” Defense Priorities, September 30, 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/the-case-for-withdrawing-from-the-middle-east.

- 32Faith Karimi, “US has Hundreds of Troops in Niger. Here’s Why,” CNN, May 10, 2018, https://www.cnn.com/2018/05/10/politics/niger-american-troops-presence.

- 33Jennifer Keister, “The Illusion of Chaos: Why Ungoverned Spaces Aren’t Ungoverned, and Why That Matters,” Cato Institute, December 9, 2014, https://www.cato.org/policy-analysis/illusion-chaos-why-ungoverned-spaces-arent-ungoverned-why-matters.

- 34Benjamin H. Friedman and Justin Logan, “Disentangling from Syria’s Civil War,” Defense Priorities, May 29, 2019, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/disentangling-from-syrias-civil-war.

- 35Stephen Van Evera, “Why Europe Matters, Why the Third World Doesn’t: American Grand Strategy After the Cold War,” Journal of Strategic Studies 13, no. 2 (1990): 1-51.

- 36Christopher Mott, “Don’t Fear China’s Belt and Road Initiative,” Global Politics and Strategy 62, no. 4 (July 2020): 47-55.

- 37The Middle East is not rich as a region—it comprises just four percent of global wealth, but oil production creates quite concentrated wealth that is potentially a boon to those who control it, including potential conquerors. Logan, “The Case for Withdrawing from the Middle East.”

- 38David Blagden and Patrick Porter, “Desert Shield of the Republic? A Realist Case for Abandoning the Middle East,” Security Studies 30, no. 1 (February 2021): 5-48.

- 39Andrew S. Weiss and Jasmine Alexander-Greene, “What’s Driving Russia’s Opportunistic Inroads with Saudi Arabia and the Gulf Arabs,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, October 5, 2022, https://carnegieendowment.org/2022/10/05/what-s-driving-russia-s-opportunistic-inroads-with-saudi-arabia-and-gulf-arabs-pub-88099.

- 40The Middle East accounts for approximately 50% of China’s crude oil imports. Jeff Baron, “Country Analysis Executive Summary: China,” U.S. Energy Information Administration, August 8, 2022, https://www.eia.gov/international/analysis/country/CHN.

More on Middle East

Featuring Daniel DePetris

February 25, 2026

Featuring Daniel Davis

February 23, 2026

Featuring Rosemary Kelanic

February 23, 2026

Events on Grand strategy