July 9, 2025

Aligning global military posture with U.S. interests

By Jennifer Kavanagh and Dan Caldwell

Key points

- The Pentagon should revise the U.S. global military posture to be consistent with protecting vital national interests based on a grand strategy of realism and restraint. This will mean reducing the size of the military footprint in certain regions and changing the mix and location of military forces in others.

- A review of the U.S. global military posture should focus on four priorities: defending the homeland, preventing the rise of a rival regional hegemon in key areas, burden shifting to allies and partners, and protecting U.S. economic security.

- The current military posture in Europe is too large, encouraging free-riding by European allies and preventing them from taking more responsibility for their own security. U.S. troop levels should be reduced to approximately where they were before Russia’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine. This will involve the withdrawal of some ground combat units, multiple fighter squadrons, and several destroyers.

- Likewise, the military posture in the Middle East is too large given limited U.S. interests and the region’s lack of an existential military threat to the U.S. homeland. Air and naval assets deployed after the 2023 attacks on Israel should be removed, post-9/11 legacy deployments in Iraq and Syria should be ended, and troops in Kuwait and Qatar should be fully withdrawn.

- The U.S. military posture in East Asia should be realigned to focus on balancing Chinese power and protecting U.S. interests. Recommended changes include removing most ground forces and two fighter squadrons from South Korea, moving U.S. forces away from the Chinese coast, and shifting more frontline defense responsibilities to allies like Japan and the Philippines.

What is the global posture review?

The U.S. military is a global force. As of 2025, over 200,000 American soldiers, sailors, Marines, and airmen were deployed at hundreds of U.S. military bases around the world.1Katharina Buchholz, “Where U.S. Troops Are Based around the World,” Statista, March 24, 2025, https://www.statista.com/chart/8720/where-us-troops-are-based-around-the-world/#:~:text=According%20to%20data%20from%20the,including%20those%20in%20the%20U.S.; “More than 200,000 Troops Deployed during the Holidays,” December 24, 2024, 13News Now, YouTube, 00:01:13, https://youtu.be/vKooxRRO204?si=MbW9RITDa1GvIJEo.

For many policymakers, this forward deployed military power is an essential tool of U.S. foreign policy. Advocates of a large and active U.S. military footprint overseas argue that U.S. troops operating abroad maintain global stability, reassure allies, protect international commerce, and prevent aggression that threatens U.S. interests.2Angela O’Mahony, et al., U.S. Presence and the Incidence of Conflict (RAND Corporation, 2018), https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR1900/RR1906/RAND_RR1906.pdf; Michael J. Lostumbo et al., Overseas Basing of U.S. Military Forces: An Assessment of Relative Costs and Strategic Benefits (RAND Corporation, 2013); Michael J. Mazarr, Understanding Defense (RAND Corporation, 2018), https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/perspectives/PE200/PE295/RAND_PE295.pdf?ref=bytesandborscht.com; Alexander L. George and Richard Smoke, Deterrence in American Foreign Policy: Theory and Practice (New York: Columbia University Press, 1974). They also argue U.S. personnel based abroad gain experience working with allies and partners, increase interoperability, and can respond to crises more quickly than if they were stationed at home.3Ben Blane and Christopher Lee, “Forward Presence, Partnership, and Deterrence: The US Army in the Indo-Pacific,” Modern War Institute at West Point, April 10, 2024, https://mwi.westpoint.edu/forward-presence-partnership-and-deterrence-the-us-army-in-the-indo-pacific/; Dave Shunk, Charles Hornick, and Dan Burkhart, “The Role of Forward Presence in U.S. Military Strategy,” Military Review (July–August 2017), 56–65, https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/Military-Review/English-Edition-Archives/July-August-2017/Shunk-Forward-Presence/.

Critics of the global U.S. military presence see things differently. They argue the U.S. military is overextended and that forward deployments provide few benefits while creating entanglements that risk pulling the United States into unnecessary wars that do not advance U.S. interests.4Miranda Priebe et al., Do Alliances and Partnerships Entangle the United States in Conflict? (RAND Corporation, 2021), https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RRA700/RRA739-3/RAND_RRA739-3.pdf. This group is more skeptical of the deterrent value of U.S. military forces. It argues that, in any case, the United States does not need a large forward military presence to be secure, as it is surrounded by water on two sides and weak neighbors to the north and south.5John M. Schuessler and Joshua R. Shifrinson, “The Insular Advantage: Geography and the Durability of American Alliances,” paper presented at the University of Notre Dame International Security Center, November 6, 2018, https://ndisc.nd.edu/assets/294013/insular_advantages_revised.pdf.

Moreover, in almost any future conflict the United States and its allies might face, they would be protecting the status quo and as a result could leverage the many benefits of defensive warfare—including lower force requirements.6Carl von Clausewitz, On War: Indexed Edition, ed. and trans. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989); Stephen Biddle, Military Power: Explaining Victory and Defeat in Modern Battle (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010); Charles L. Glaser and Chain Kaufmann, “What is the Offense-Defense Balance and Can We Measure It?” International Security 22, no. 4 (1998): 44–82, https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/6/article/446911/summary; “ADP 3-0 Unified Land Operations,” Department of the Army, October 2011, https://www.army.mil/e2/downloads/rv7/info/references/ADP_3-0_ULO_Oct_2011_APD.pdf; The Command and General Staff School, Lieutenant Colonel GR Meyer, “Doctrines of the Defensive,” Quarterly Review of Military Literature, vol. XIX, no. 73 (1939), https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/military-review/Archives/English/100-Landing/Topics-Interest/Doctrine/June-1939-Meyer.pdf. Critics suggest that a strong U.S. security blanket turns allies and partners into free-riders that underinvest in their own military.

Apart from its benefits, risks, and costs, the U.S. forward military posture can be difficult to change. Once forces are sent abroad, the United States is often slow to bring them back home, even when the threat or mission that prompted the initial deployment ends. As a result, it is common for the number of U.S. forces stationed overseas to increase over time, as what was a surge posture slowly becomes the new status quo. This can rapidly lead to a fundamental misalignment between U.S. military presence and U.S. national security and strategic interests.

To weigh these different factors and considerations, when new leaders arrive in the Pentagon following a change in presidential administrations, they typically launch a Global Posture Review (GPR). The GPR is intended to evaluate the locations and numbers of U.S. military forces stationed overseas and make adjustments based on an updated threat assessment and the new administration’s reading of U.S. interests and priorities. While the results of the review are typically classified, an unclassified summary is usually released, especially when major changes are planned.

The last Global Posture Review was released in November 2021, about 10 months into President Joe Biden’s term. For many observers, the 2021 review was a disappointment that failed to respond to changes in the global balance of power or to reflect emerging limits and constraints on American military power. After much hype, the document concluded that the U.S. military posture was generally aligned with U.S. needs and interests and recommended few major changes.7Peter Brookes, “Venezuelans’ Fight for Freedom Important to U.S.,” Heritage Foundation, February 27, 2014, https://www.heritage.org/defense/commentary/joe-bidens-global-posture-review-was-nothingburger; Becca Wasser, “The Unmet Promise of the Global Posture Review,” War on the Rocks, December 30, 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/12/the-unmet-promise-of-the-global-posture-review/. Most significantly for the review’s critics, the Biden team failed to notably increase the U.S. posture allocated to Asia, failing to meet one of its early policy commitments.

Outside of Biden’s GPR, over the four years of Biden’s tenure, the U.S. global posture became more bloated and imbalanced. After arriving in office, the administration canceled the withdrawal of 12,000 troops from Germany that had been planned under the first Trump administration and increased the U.S. presence in Europe by another 20,000 troops after the Russian invasion of Ukraine.8Jim Garamone, “Biden Announces Changes in U.S. Force Posture in Europe,” Department of Defense, June 29, 2022, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3078087/biden-announces-changes-in-us-force-posture-in-europe/. Following the October 7, 2023 Hamas attack on Israel, Biden began a series of U.S. posture increases in the Middle East, including sending additional naval, air defense, and tactical air assets to the region.9Garamone, “Biden Announces Changes.” Biden’s Pentagon also increased the number of U.S. forces rotationally deployed in Africa, supporting counterterror operations and train-and-assist missions.10Charlie Savage and Eric Schmitt, “Biden Approves Plan to Redeploy Several Hundred Ground Forces Into Somalia,” New York Times, May 16, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/16/us/politics/biden-military-somalia.html. Changes made in Asia were comparatively small. There, the Biden team signed the AUKUS agreement (which would change posture only in the longer term), gained access to four additional bases in the Philippines, and made permanent some previously rotational deployments in South Korea.11Wasser, “The Unmet Promise”; “Biden Announces Deal to Sell Nuclear-Powered Submarines to Australia,” CBS News, March 13, 2023, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/australia-submarine-deal-biden-san-diego-aukus/.

As it conducts its posture review, the Trump administration has a chance to realign the United States’ global military footprint with U.S. national interests, correcting the mistakes of the Biden years and the lingering aftereffects of the global war on terror. This report aims to assist Pentagon officials as they carry out their posture review and decide how they will reshape the U.S. military posture over the next four years. It makes posture recommendations that are consistent with the Trump administration’s stated national security priorities and that advance core U.S. interests by narrowing U.S. military commitments and moving toward a grand strategy of restraint.

The next section of the report lays out the priorities used to guide our review and recommendations as well as our assumptions. We then devote one section to each of the three major regions—Europe, the Middle East, and Asia—and one section to other global missions. In each we discuss the current U.S. posture and then our recommended changes and their rationales. We conclude by summarizing and describing the implications of the posture changes we propose for U.S. national security.

Assumptions and priorities

The guidance offered by the 2025 posture review should advance U.S. vital interests and match the administration’s national security priorities. The Trump administration has rightly indicated that its foreign policy will put American interests first, aim for “peace through strength,” and adhere to the principles of realism and restraint in its engagements abroad.12Robert C. O’Brien, “The Return of Peace through Strength,” Foreign Affairs, June 18, 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/return-peace-strength-trump-obrien. Vice President JD Vance told Naval Academy graduates in May 2025, “We’re returning to a strategy grounded in realism and protecting our core national interests… this doesn’t mean that we ignore threats, but it means that we approach them with discipline and that when we send [the U.S. military] to war, we do it with a very specific set of goals in mind.”13C. Todd Lopez, “Vance Tells Midshipmen Their Service Will Not Be Squandered on Rudderless Missions,” Department of Defense, May 23, 2025, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/4196829/vance-tells-midshipmen-their-service-will-not-be-squandered-on-rudderless-missi/.

Trump and his national security team have defined U.S. interests more narrowly than his recent predecessors. The administration has made clear that homeland security is the number one priority—ranking above overseas threats and missions.14Alex Horton and Hannah Natanson, “Secret Pentagon Memo on China, Homeland Has Heritage Fingerprints,” Washington Post, March 29, 2025, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/2025/03/29/secret-pentagon-memo-hegseth-heritage-foundation-china/. It has also drawn a clear line between U.S. interests and those of allies (even close ones) and adopted a different view of the threats facing the United States than the Biden administration. It has, for instance, accepted a more benign assessment of the conventional threat posed to the United States by Russia and deprioritized operations against terrorist groups that cannot strike the U.S. homeland directly.15Horton and Natanson, “Secret Pentagon Memo”; Katharine Houreld and Mohamed Gobobe, “How U.S. Cuts in Somalia Could Imperil the Fight against Al-Shabab,” Washington Post, May 27, 2025, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2025/05/27/somalia-al-shabab-american-troops-trump/.

The recommendations in this report reflect our assessment of how the administration can use posture changes to pursue its objectives. In general terms, we recommend that the Pentagon revise the U.S. posture to be more consistent with a grand strategy of realism and restraint, which would shift the focus of U.S. military commitments from sustaining U.S. global primacy to maintaining favorable balances of power in key regions. In practice, this would involve allies assuming more responsibility for frontline defense roles while the U.S. global military footprint would shrink in size and focus on defending core U.S interests and in support of allies.16“Opening Remarks by Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth at Ukraine Defense Contact Group (As Delivered),” U.S. Department of Defense, February 12, 2025, https://www.defense.gov/News/Speeches/Speech/Article/4064113/opening-remarks-by-secretary-of-defense-pete-hegseth-at-ukraine-defense-contact/; “Secretary Marco Rubio with Megyn Kelly of the Megyn Kelly Show,” U.S. Department of State, January 30, 2025, https://www.state.gov/secretary-marco-rubio-with-megyn-kelly-of-the-megyn-kelly-show/.

To advance this foreign policy vision, we define four main national security priorities that guide our posture recommendations.

- Defend the homeland. The administration has put homeland defense as its top priority, including defending U.S. airspace and coasts, as well its northern and southern borders. U.S. posture decisions at home and abroad should support this goal, ensuring sufficient forces and resources are available for defense of the United States, its coasts, and airspace.17David Vergun, “Pentagon Prioritizes Homeland Defense, Warfighting, Slashing Wasteful Spending,” U.S. Department of Defense, February 9, 2025, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/4060775/pentagon-prioritizes-homeland-defense-warfighting-slashing-wasteful-spending/.

- Prevent the rise of a regional hegemon in Asia, Europe, or the Middle East. To maintain favorable balances of power in key regions of the world, the United States will need to prevent the rise of a rival regional hegemon in Eurasia, that is, a state able to amass a preponderance of power in Asia, Europe, or the Middle East and use that power to challenge or constrain U.S. interests.18Miranda Priebe et al., “Competing Visions of Restraint,” International Security vol. 49, no. 2, 135–169, https://direct.mit.edu/isec/article/49/2/135/125212/Competing-Visions-of-Restraint. In Europe and the Middle East, the prospects for the emergence of a new dominant regional power are remote. In Asia, China does not yet have a path to regional hegemony, but it has enough power to prevent the United States from sustaining sole regional dominance. The United States should make posture decisions that bolster its ability to balance the power of regional rivals, in particular China.19Kelly A. Grieco and Jennifer Kavanagh, “America Can’t Surpass China’s Power in Asia,” Foreign Affairs, January 16, 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/america-cant-surpass-chinas-power-asia This might include reinforcing the U.S. military presence at strategic locations such as in Japan, along the second island chain in Asia, or at key maritime chokepoints in the Middle East or Northern Europe.

- Burden shift to allies and partners. Even as it pursues a balance of power strategy, the United States should require that allies and partners take greater and ultimately complete responsibility for their own defense. This will require shifting defense burdens that the United States currently carries on to allies and keeping U.S. forces only where they are required to guarantee and protect U.S. interests. The United States should be able to reduce its overseas military presence as it offloads responsibilities, sometimes significantly. The United States does not need for allies to step up before pulling back but it should offer allies clear and transparent timelines for U.S. retrenchment. What and how much burden shifting occurs may vary by region.20“Remarks by Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth at the 2025 Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore (As Delivered),” U.S. Department of Defense, May 31, 2025, https://www.defense.gov/News/Speeches/Speech/Article/4202494/remarks-by-secretary-of-defense-pete-hegseth-at-the-2025-shangri-la-dialogue-in/; “Pete Hegseth at Ukraine.”

- Protect U.S. economic security. Economic security is a core element of national security and the United States should be willing to use military power, including forward presence where necessary, to protect U.S. access to key waterways and natural resources.

In addition to these priorities, to guide our posture review, we adopt a set of assumptions. First, we assume that the Pentagon will have mostly flat budgets. Trump’s first “skinny budget” request included a largely flat budget request for the Department of Defense, and although the reconciliation bill—if passed—will give the military an extra $150 billion to spread over five years, this should be a one-time plus up.21Joe Gould et al., “Making Sense of Trump’s Defense Spending Math,” Politico, May 5, 2025, https://www.politico.com/newsletters/national-security-daily/2025/05/05/making-sense-of-trumps-defense-spending-math-00329045.

Second, we consider only changes that can be completed over the course of Trump’s term to ensure that our recommendations are realistic and take into account bureaucratic and bandwidth challenges. After all, an administration can only accomplish so much. In addition to the time needed to make and implement decisions, there are logistical concerns, including finding space for forces redeployed from abroad to the United States and decommissioning units that are cut from the force entirely.

Finally, we assume the United States does not make any new territorial acquisitions. This does not rule out the possibility of posture increases to serve key strategic ends, but it does exclude the type of posture increases that would be required if the United States were to expand its borders.

Posture changes in Europe: A return to 2014

The current U.S. military presence in Europe includes around 90,000 soldiers and airmen along with seven fighter squadrons and their support units; intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance assets; and a naval presence that includes five destroyers based at Rota in Spain. Germany currently hosts about 39,000 personnel and one fighter squadron—the largest concentration of U.S. forces on the European continent. U.S. forces are also based in Italy (13,000 personnel and two fighter squadrons), Romania (5,000), Poland (14,000), and the United Kingdom (10,000 and four fighter squadrons). The United States also maintains smaller rotational deployments in the Baltic states. More posture increases are planned in the near term, including the deployment in February 2026 of a 500-person Army multi-domain task force (MDTF) and an additional (sixth) Navy destroyer. At times, this presence has been supplemented by carrier strike groups in the Mediterranean Sea.22Molly Carlough, Benjamin Harris, and Abi McGowan, “Where Are U.S. Forces Deployed in Europe?” Council on Foreign Relations, February 27, 2025, https://www.cfr.org/article/where-are-us-forces-deployed-europe.

Though, of course, this posture is significantly lower than during the Cold War when the United States had hundreds of thousands of troops based forward in Europe, it is a large increase over the 60,000 or so that were in the theater in 2013, prior to Russia’s first invasion of Ukraine. Under Biden, about 20,000 additional U.S. Army forces were moved into the region, along with additional airpower, following Russia’s full invasion of Ukraine in 2022. This surge presence remains largely in the region to this day.

The problems with posture in Europe today

There are four major issues with the U.S. posture in Europe today. First, it is too large given an objective assessment of the threats from the region. The primary driver of the U.S. military presence in Europe has always been the perceived threat posed by Russia (originally the Soviet Union), both to U.S. NATO allies and to the United States itself. Forces stationed forward have thus typically had a dual role—to deter and defend against attacks aimed at allies and to form a security perimeter that prevents Russia from presenting a direct threat to the United States.

Russia’s performance in Ukraine, however, suggests it does not pose a significant conventional military threat to the United States and presents only a moderate threat to NATO allies. Of course, this threat varies across the European continent, being most acute for states closest to Russia on NATO’s eastern flank.23Claudia Chiappa and Joshua Posaner, “Russia Would Lose a War with NATO, Poland Warns,” Politico, April 25, 2024, https://www.politico.eu/article/russia-would-lose-in-a-war-with-nato-polish-fm-warns/; Russian Military Performance and Outlook, Congressional Research Service, May 28, 2025, https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/25956318-if126065/. Given its slow progress in Ukraine—a small country fighting with a shortage of weapons—it is unlikely that Russia could, for instance, mount a campaign capable of taking control of vast chunks of European territory before being stopped by European forces.

With the advantages of defensive warfare—including the ability to prepare terrain ahead of time with barriers and minefields, exploit geographic advantages for surveillance and force placement, and use cheap technologies like drones to limit adversary progress—Europe likely has the military capabilities today (even before rearming) to prevent widespread Russian military gains were Moscow to attack a NATO member.24Barry R. Posen, “Europe Can Defend Itself,” Global Politics and Strategy 62, no. 6 (2020): 7–34, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00396338.2020.1851080. A clear-eyed view of the Russian threat suggests that the United States does not need a large footprint to safeguard its own security or guarantee Europe’s.

Second, the current U.S. military presence is out of proportion with U.S. interests in Europe. The United States has long used its military presence to prevent the rise of a European hegemon, protect its economic interests in Europe, and build leverage and influence over European allies. Today, it is not clear a large forward presence in Europe helps Washington achieve these aims.

The risk that a European hegemon will emerge is low with or without U.S. forces present. It seems unlikely that any one European country will be able to establish a position of regional dominance given internal divisions, and equally unlikely that Russia will be able to fight its way to a large European sphere of influence. At the same time, there is little evidence that a large forward military presence is the best or only way to protect whatever economic interests the United States has in Europe or that it offers policymakers the leverage they seek. European leaders act independently on many policy issues, despite the large U.S. military presence.

Third, the U.S. military presence in Europe encourages underspending and free-riding by U.S. allies that leaves Washington footing the bill for Europe’s security, even though a rich and technologically advanced Europe can afford to defend itself.25Justin Logan, “Uncle Sucker: Why U.S. Efforts at Defense Burdensharing Fail,” Cato Institute, March 7, 2023, https://www.cato.org/policy-analysis/uncle-sucker. Not only does this arrangement put the United States at risk of being entangled in Europe’s wars and security crises even if its own interests are not at stake, but it forces the United States to expend scarce resources in ways not always aligned with its core interests. The Trump administration has been clear from day one that it expects Europe to spend and do more in the security domain so the United States can spend and do less, with the goal of Europe taking full responsibility for its own security. This would be better for the United States, as it would conserve resources and reduce risk, but it would also be better for Europe to be geopolitically self-sufficient.

Finally, a large forward military posture in Europe absorbs resources that are needed in higher priority theaters, including Asia, where the United States faces its strongest competitor, and the U.S. homeland.26Alex Velez-Green and Robert Peters, “The Prioritization Imperative: A Strategy to Defend America’s Interests in a More Dangerous World,” Heritage Foundation, August 1, 2024, https://www.heritage.org/defense/report/the-prioritization-imperative-strategy-defend-americas-interests-more-dangerous. A large military footprint in Europe, therefore, has a high opportunity cost given other U.S. military commitments and priorities.

In some cases, these tradeoffs are direct. Every soldier deployed in Europe is one that cannot be used in the administration’s homeland defense missions. Every air defense system or fighter squadron deployed in Europe is one that is not immediately available for a crisis in Asia. Other tradeoffs are indirect. Dollars spent on ground warfare capabilities primarily for the European theater, for instance, cannot also be invested in new ships and submarines needed to support Indo-Pacific operations. That these tradeoffs exist raises the opportunity cost of assets and capabilities deployed in Europe and the importance of rightsizing the U.S. commitment in Europe to match prevailing threats and U.S. interests.

Principles to guide a revised U.S. posture in Europe

A revised U.S. posture in Europe would be guided by four principles. First and most importantly, the goal of posture changes would be to shift from a U.S.-based regional security architecture to a security architecture led by Europe’s member states. Achieving this outcome would involve keeping only those U.S. forces in Europe that are required to safeguard U.S. interests and shifting to allies and partners all other responsibilities.

This transition should occur even if Europe cannot immediately backfill redeployed U.S. military capabilities, but it will also likely need to be phased, not to make it easier on Europe but to allow the Pentagon time to make rotation, basing, and force structure decisions as large numbers of U.S. forces come home. Among the first changes that should be made, however, is the shift of frontline defense roles to European allies, leaving the United States to focus on combat support capabilities and defensive roles.

Second, posture changes would seek to free up those assets currently based in Europe that could be important in an Indo-Pacific war or to defend the homeland. This might include air defense, some naval assets, fighter squadrons, and even ground units needed to support the ongoing Army deployment at the U.S. border.

Third, recognizing that any military campaign fought against Russia in Europe would be defensive, posture changes should aim to exploit the defender’s advantage in modern warfare. In addition to lowering personnel requirements for a successful campaign, a focus on defensive operations and advantages will reduce the need for and benefit of certain types of offensive systems like long-range strike weapons and advanced fighter jets. Instead of deploying these assets to Europe, a revised U.S. posture would be made up mostly of support forces, including logistics, sustainment, intelligence, and maintenance, and some heavier ground forces able to serve as a defensive perimeter.

Finally, a revised posture should consider the value of European-based assets and personnel for power projection into other theaters, for example intelligence and reconnaissance activities in the Black Sea or crisis response operations in the Middle East.

Recommendations

The posture changes we recommend for Europe would ultimately reduce the number of ground forces by about 30,000 and cut air and naval forces by about half compared to their levels today. This would bring the U.S. military posture in the region close to its 2013 levels—that is, what U.S. military presence in Europe looked like prior to Russia’s first invasion of Ukraine in 2014. This should not be the end point of the U.S. military drawdown in Europe. Over the next decade, as Europe steps up its defense capabilities, the U.S. military presence in the region should fall further, perhaps to something like 20,000 ground forces and a small air and naval presence. But the changes outlined here are realistic goals for the next four years.

Starting with ground forces, we recommend withdrawing three brigade combat teams (BCT) (amounting to about 5,000 personnel per BCT, including the BCT itself and associated support forces) from Europe and returning them stateside, including the brigade combat team in Romania and either two BCTs from Poland or one from Germany and one from Poland. This would leave two BCTs forward-stationed in Europe, including the 173rd Airborne Brigade stationed in Italy. In addition, we recommend removing one combat aviation brigade (CAB), the division headquarters located in Romania, and associated support forces. Notably, these changes would also end U.S. contributions to the enhanced force protection deployments in the Baltic states, which are typically drawn from BCTs in Poland and Germany.

Of these forces, rotational units could be removed quickly. Once rotated home, they would simply not be replaced. Units permanently based in Europe would take more time to remove, as space at U.S. bases would have to be found for associated personnel—unless the units are cut entirely to reduce Army force structure. This could be done more quickly, though even then remaining personnel would need to be reassigned.

The rationale for these changes is straightforward. First, the U.S. push for burden shifting demands that European allies take the lead in their own self-defense, including especially ground combat operations and the defense of NATO’s eastern border. Removing U.S. ground combat units immediately gives Europe the incentive and the impetus to step up and fill this gap by building its own combat brigades and adjusting its collective posture in NATO frontline states.

Second, as already noted, the Trump administration has correctly assessed that Russia poses little direct threat to U.S. interests, and it certainly does not present a greater threat to U.S. interests than it did in 2014. Nothing about Russia’s first or second invasion of Ukraine changed the nature or extent of the conventional threat Russia poses to the U.S. homeland, and elevated concern about the Russian threat to Europe—the driver of the 20,000-troop surge under President Joe Biden—should have dissipated after Russia’s lackluster battlefield performance. It therefore makes little sense for the United States to keep five combat brigades in Europe, especially given the likely defensive nature of any U.S. military operation on the European continent.

In addition to withdrawing the combat and aviation brigades, we recommend canceling the planned February 2026 deployment of the MDTF and its intermediate-range missile capabilities to Germany. This deployment is not consistent with the Trump administration’s assessment of the Russian threat or its desire to reduce the U.S. role in European security. The MDTF and its long-range missiles are not defensive capabilities and are more likely to provoke Russia than to deter, capable as they are of striking deep into Russian territory. If the U.S. intent is to step back from Europe and let Europe manage its own defense, it hardly makes sense at the same time to deploy an aggressive and destabilizing new missile platform to the region.

Turning to air forces, we recommend cutting the number of U.S. fighter squadrons based in Europe from seven to four, returning to around 2014 levels. In congressional testimony in May 2025, Air Force officials announced their intention to remove two F-15 fighter squadrons from the United Kingdom and return them to the United States for a rest and refit period. This likely reflects the Pentagon’s efforts to remove from Europe assets that might be needed in Asia, giving them time for repairs and modernization as required.

At the time, the Air Force did not specify what would replace the F-15 squadrons. Under our recommendations, they would not be replaced and associated personnel would also be removed, leaving just the two F-35 squadrons and various enablers in the United Kingdom plus about 7,500 servicemembers. In addition to this change, we recommend removing one F-16 fighter squadron from Italy. This would leave four total fighter squadrons in Europe. We would also cut air support units—maintenance, air tankers, and others—by 50 percent, returning them to the United States where they can be readied for future deployments as needed.

As in the case of ground forces, the current level of U.S. airpower deployed in Europe vastly exceeds requirements. Not only do European countries have their own fighter aircraft but several have made large purchases to expand their fleets of U.S.- and European-made jets in the near term. If anything, the United States should have less airpower deployed forward in Europe now compared to 2014. Not only is the Russian threat largely unchanged from the U.S. perspective, but the United States is no longer involved in large-scale counter-ISIS operations and does not need to use European airbases to project power into the Middle East to the same extent. Though concerns about the war between Israel and Iran may drive temporary increases in U.S. airpower in Europe, a staging area for the Middle East, these forces too should be returned home as soon as the situation stabilizes.

U.S. naval power in Europe should also be cut in half, from the six destroyers currently planned for Rota to the three destroyers that were based there prior to 2014. The increase in the U.S. naval presence over the past decade was intended to bolster Europe’s ballistic missile defenses following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but even if the additional air defenses were required at one point, a Russian air assault on Europe at this point seems a remote possibility. Moreover, air defense assets are among the scarcest capabilities in the U.S. arsenal and among the systems that would be most central to an Indo-Pacific conflict. Cutting the deployment of U.S. naval power to three destroyers would free up resources for U.S. operations in the higher priority Indo-Pacific theater.

In addition to adjusting the number of forward-deployed destroyers in Europe, we recommend curtailing planned future carrier strike group deployments to the Mediterranean Sea. Looking at the number of U.S. partners bordering this body of water—Spain, France, Italy, and Turkey—makes clear the array of allied naval power in the region. This is a prime opportunity for burden shifting. These allies should be capable of managing security in this strategic body of water with significantly less U.S. support. In any case, because the United States does not rely much on trade through the Suez Canal, it would be relatively insulated from disruptions should they occur. This change would increase the availability of carriers for operations elsewhere, including in Asia, or for modernization and repairs in preparation for future requirements.

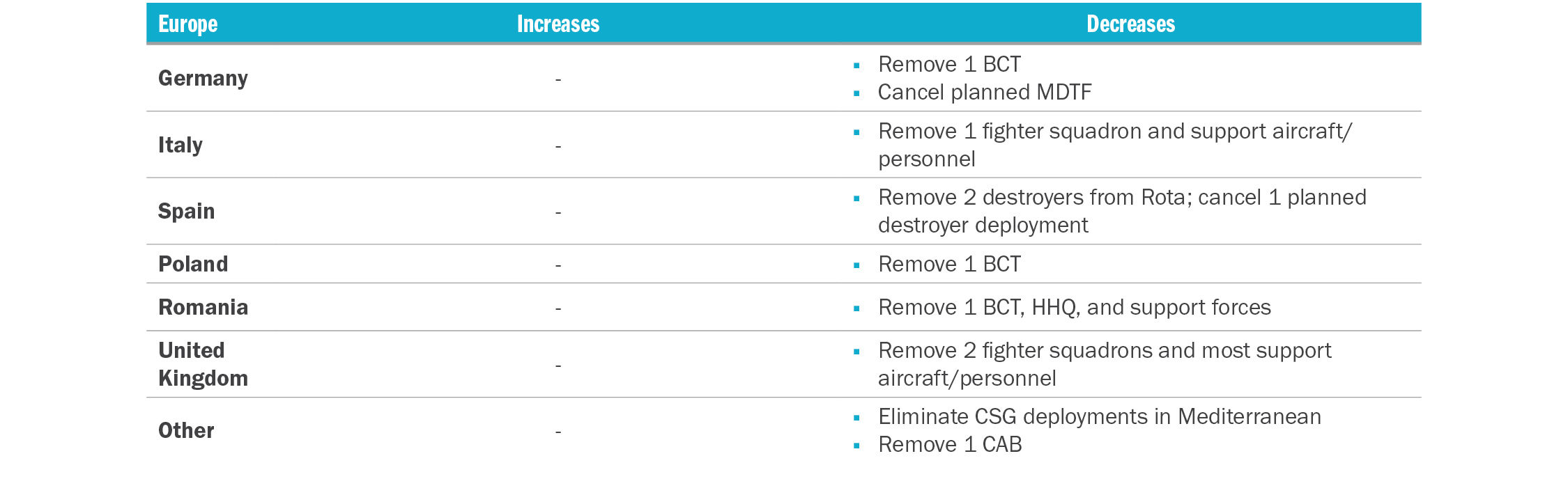

Overall, then, our recommended cuts to the U.S. posture in Europe would:

- Remove three ground combat brigades, a combat aviation combat brigade, a headquarters unit, and the planned MDTF deployment.

- Cut U.S. airpower and naval power in the region by approximately 50 percent.

Together, these changes would reduce the overall U.S. footprint in Europe by 40–50 percent over four years and return the U.S. posture to largely pre-2014 levels. The adjustments we recommend would accomplish significant burden shifting to allies, maintain key intelligence and power projection assets, redeploy high-demand capabilities likely to be needed in Asia or for homeland defense, and better align U.S. commitments in Europe with the level and type of threat posed by Russia to U.S. interests.

Planned cuts could occur in a phased manner, with some ground combat and aviation units leaving immediately and others withdrawn later on an agreed upon schedule. However, the United States should not wait until Europe is able to replace U.S. capabilities before making the changes outlined here.

Recommended posture changes: Europe

Posture changes in the Middle East: Remove surge forces and end the forever wars

The U.S. military posture in the Middle East today is lower than it was during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, but it still far exceeds U.S. interests at stake in the region. This is especially true after the surge in U.S. forces to the region following the October 7 Hamas attack, the subsequent U.S. bombing campaign against the Houthis in Yemen, and, most recently, the Israel-Iran war that saw the United States provide defensive support to Israel and conduct offensive strikes against Iran.

At present, the United States has something close to 40,000 forces deployed in the Middle East, along with aircraft and warships. The Trump administration has already started removing some of the 2,000 soldiers based in Syria but has not yet announced a full withdrawal.27Aaron Sobczak, “Ambassador: US to Reduce Military Bases in Syria ‘to One,’” Responsible Statecraft, June 2, 2025, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/american-troops-in-syria-drawdown/. The 2,500-strong troop presence in Iraq is also slated for cuts after a deal with the Iraqi government. If the reported deal is carried out as planned, that would leave just a few hundred soldiers in Erbil by the end of 2026.28Luis Martinez and Matt Seyler, “US Not Withdrawing from Iraq but Agreement Could Lead to Troop Reductions,” ABC News, September 27, 2024, https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/us-withdrawing-iraq-agreement-lead-troop-reductions/story?id=114296946.

Elsewhere the U.S. military presence is even larger. The United States has 13,500 forces in Kuwait, 5,000 in UAE, about 3,000 in Saudi Arabia, about 10,000 in Qatar, 3,000 in Jordan, and about 9,000 in Bahrain where the U.S. Navy’s Fifth Fleet is based. In addition to these personnel, the United States typically maintains four or five fighter squadrons, some based in the region permanently and some on a rotational basis. Since the October 7 attacks, the United States has also deployed more air defense to the region, sending several additional Patriot batteries and two Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) systems to Israel, each along with about 100 personnel.

Additionally, the United States typically maintains at least one carrier strike group (CSG) in the Red Sea or Persian Gulf. After October 7, this presence was augmented, at points by another CSG to support operations against the Houthis. For a time, the United States also deployed a Marine Corps amphibious ship, the USS Wasp, to the eastern Mediterranean, also the home of additional CSGs at times. Four littoral combat ships (LCS) and one mine countermeasures ships (MCMs) are also homeported at the naval base in Bahrain.29Jonathan Masters and Will Merrow, “U.S. Forces in the Middle East: Mapping the Military Presence,” Council on Foreign Relations, March 28, 2025, https://www.cfr.org/article/us-forces-middle-east-mapping-military-presence.

The problems with U.S. posture in the Middle East today

The most fundamental problem with the U.S. posture in the Middle East today is that it is far too large for the U.S. interests at stake. Though the region is fraught with instability and conflict, there are few direct threats to U.S. national security. Receiving the most attention over recent months is the supposed threat posed to the United States and its regional partners by Iran’s nuclear program. Those supportive of a large U.S. presence in the Middle East argue it’s necessary to deter Iran from striking Israel directly or targeting other U.S. assets and interests and to provide a credible military threat to back up diplomatic efforts aimed at reining in Iran’s nuclear program.

But these arguments are misleading. While a nuclear-armed Iran is not ideal, it does not pose an existential threat to the United States, as Tehran has no delivery vehicles capable of reaching the U.S. homeland.30Dan Caldwell and Simone Ledeen, “Debate: Should the U.S. intervene in Iran,” Free Press, June 16, 2025, https://www.thefp.com/p/debate-should-the-us-intervene-in. Israel might view the threat posed by a nuclear Iran differently, but the interests of a U.S. partner—one that itself has nuclear weapons and receives significant U.S. military aid—should not solely drive the U.S. posture in the region.

Finally, there is no military approach—short of an invasion and full occupation of Iran—that can permanently eliminate Iran’s path to a nuclear weapon. As seen in recent weeks, strikes on the country’s nuclear sites may set the program back without destroying it, allowing Iran to reconstitute and even speed up its program over time.31Julian Barnes et al, “Strike Set Back Iran’s Nuclear Program by Only a Few Months, U.S. Report Says,” New York Times, June 24, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/06/24/us/politics/iran-nuclear-sites.html. There is also little evidence that the U.S. military presence in the region influences the calculations of Iran’s leadership when it comes to the country’s nuclear program or its wider regional military strategy.32James Acton, “The United States Should Stay Out of the Israel-Iran War,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, June 13, 2025, https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2025/06/israel-attack-iran-strike-us-response?lang=en. In fact, if anything, the U.S. military presence in the Middle East creates vulnerabilities and risks for the United States. It is only because these forces are deployed throughout the region that Iran’s missiles pose any direct challenge to the United States at all.

Beyond Iran, U.S. interests in the Middle East are similarly limited. The United States does not rely heavily on trade routes running through the region, and although it is affected by disruptions to regional shipping that affect oil prices, shocks severe enough to cause major price spikes are rare. The Middle East region is home to a large number of non-state terrorist actors, but none pose a significant threat to the U.S. homeland.33Aaron David Miller and Richard Sokolsky, “The Middle East Just Doesn’t Matter as Much Any Longer,” Politico, September 3, 2020, https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2020/09/03/the-middle-east-just-doesnt-matter-as-much-any-longer-407820; Justin Logan, “The Case for Withdrawing from the Middle East,” Defense Priorities, September 30, 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/reports/the-case-for-withdrawing-from-the-middle-east/. Most of the challenges facing the region require political rather than military solutions, and these can come only from local actors.

Some elements of the U.S. military posture in Middle East are holdovers from the past—U.S. operations during the post-Cold War period and the two-decade-long U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Following its 2003 invasion of Iraq, the United States had up to 150,000 troops in Iraq alone, with more spread across the region. Remaining forces in Iraq, Syria, and to an extent Jordan are all examples of this “holdover” posture. Even with new missions, the remaining U.S. forces in these locations contribute to an imbalance between U.S. commitments and U.S. interests.

A second problem with today’s Middle East posture is that it leaves U.S. forces exposed to attacks from insurgent groups and Iranian munitions, while creating a looming and unnecessary risk of entanglement in wars that are not in U.S. interests.34Reid Smith and Jason Beardsley, “The U.S. Must Learn to Leave Iraq,” Foreign Policy, October 15, 2024, https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/10/15/us-must-learn-to-leave-iraq-war-troops-withdrawal/; Jonathan Hoffman, “US Is Barreling toward Another War in the Middle East,” Responsible Statecraft, November 6, 2023, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/us-middle-east/. With so many forces based in the Middle East, the United States is naturally implicated in any incidence of instability or conflict that occurs. The primary threat Iran presents to the United States, in fact, is that posed directly to U.S. forces based in the Middle East, not to the U.S. homeland itself. When Israel and Iran launched their tit-for-tat missile strikes in 2024, there were fears that U.S. forces might be caught in the crossfire, necessitating a larger U.S. military involvement. And indeed, U.S. forces were targeted by rocket and missile fire from militant groups in the region, leading to several deaths.

Small concentrations of U.S. forces in Iraq and Syria are especially vulnerable, as they often lack the necessary air defense protection. The risk of entanglement and the vulnerability of U.S. forces has emerged again in recent weeks, this time on a larger and more serious scale, as Iran and Israel trade missile salvos. After the United States hit Iran’s nuclear targets, Iran retaliated by firing missiles at Al-Udeid Air Base in Qatar. Casualties were avoided, but the attack was still a reminder that U.S. forces in the region are as much a risk and burden as a benefit.35Julian Barnes et al, “Iran Is Preparing Missiles for Possible Retaliatory Strikes on U.S. Bases, Officials Say,” New York Times, June 17, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/06/17/us/politics/iran-israel-us-bases.html.

A third problem with the U.S. posture in the Middle East is that it encourages free-riding and moral hazard. As in other areas, the large U.S. military presence has allowed regional allies and partners to underinvest in their own defense, confident that the United States will step in to manage any crisis that might occur. When the Houthis disrupted shipping in the Red Sea with missile attacks, for instance, the United States received little assistance from regional states or European navies in its campaign to restore freedom of navigation—despite the fact that these allies and partners are considerably more dependent on shipping through the region’s waterways than the United States.36Abigail Hauslohner and Ellen Nakashima, “Arab States Resist U.S. Pressure to Denounce Houthis,” Washington Post, November 3, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/2024/11/03/us-yemen-houthis-israel-arab-states/.

There are similar concerns about the way the large U.S. presence in the region encourages risk taking by Israel. When Israel decided to move ahead with its strikes on Iranian nuclear and regime targets, it was with the knowledge that the United States would likely offer at least defensive support and possible offensive assistance. Without this backstop, Jerusalem might have made a different set of choices.

Finally, there is the question of regional tradeoffs. Many of the systems and much of the materiel, including the aircraft, ships, air defense, and munitions stockpiles currently in the Middle East, would also be needed in a war in Asia. While they are deployed in the Middle East, they are not available for rapid deployment to a crisis in the Indo-Pacific.37Velez-Green and Peters, “The Prioritization Imperative”; Logan, “The Case for Withdrawing.” In the case of munitions, once expended, they take months or years to replace. Extended deployments and the wear and tear caused by the Middle East’s harsh climate means that equipment requires long rest and refit periods after returning stateside. Even more so than the large U.S. presence in Europe, continued U.S. military involvement in the Middle East constitutes a drag on the U.S. ability to make needed commitments in Asia.

Principles to guide a revised U.S. posture in the Middle East

A revised Middle East posture better aligned with U.S. interests would reduce the U.S. military presence to reflect the narrow scope of those interests and the limited nature of regional threats. It would do this by making a few specific changes.

First, a revised regional posture would return the additional air and naval power and air defense assets deployed to the theater after October 7, 2023 to the United States or the Indo-Pacific as needed. It would undo recent moves intended to “prepare the theater” for the now-ended campaign against the Houthis or recently concluded war with Iran. These moves would recalibrate the regional posture to match the current level of threat, which is not clearly higher than prior to October 2023, while also supporting regional de-escalation and shifting responsibility for the region’s defense to partners including Israel and friendly states in the Persian Gulf.

In addition to a return to pre-October 2023 force levels, a revised Middle East posture would target four other areas for retrenchment. First, it would end legacy deployments from the post-9/11 wars. Twenty-four years after 9/11, there is simply no reason for these posture elements to remain. Second, it would remove U.S. forces from areas where they are most vulnerable to attacks by militant groups and where the risk of entanglement in a costly and unnecessary war is highest. Recent regional escalation has only made this type of retrenchment more urgent to improve force protection and reduce U.S. exposure. Third, it would redeploy assets and capabilities that can contribute to deterrence and defense in the Indo-Pacific either directly to Asia or first to the U.S. homeland. Finally, it would seize opportunities to burden shift regional security responsibilities so that U.S. forces are involved only where core national interests are at stake. This would include putting regional partners in the lead in frontline defense roles in air and sea domains.

While retrenching, however, the United States will still want to retain the capability to respond to a crisis that does affect U.S. interests. Some air and naval power left in the region along with rotational deployments to the Diego Garcia military base should address this challenge.

Recommendations

The first set of recommended changes to the Middle East posture focuses on ending the post-9/11 deployments and removing U.S. military forces from areas where they are most vulnerable. We recommend cutting U.S. military forces in Syria to zero and sticking with the planned withdrawal of most U.S. forces from Iraq in 2025. These forces are among the most directly and frequently threatened by militant groups in the region (including those associated with Iran), so removing them will dramatically reduce the risk of U.S. servicemember fatalities and the chance of an unintended entanglement in a regional war. A complete withdrawal of U.S. personnel from Syria and Iraq would also mark an end to the deployments associated with the post-9/11 wars and counter-ISIS campaigns.

Critics will complain that these changes open the door for a resurgence of insurgent activity, but Middle East insurgent groups do not threaten the United States. Neither the remnants of ISIS nor other groups in Iraq or Syria can target the U.S. homeland. At this point, the remnants of such insurgencies are best and more efficiently dealt with by regional partners, including local forces in Syria, Iraq, and Turkey, rather than U.S. military personnel. If absolutely required, the United States can use “over the horizon” (or long-range) strikes to target key insurgent group leaders or their military stockpiles.38Gil Barndollar, “Dealing with the Remnants of ISIS,” Defense Priorities, February 11, 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/dealing-with-the-remnants-of-isis/.

Once these forces are removed from Syria and Iraq, two other withdrawals become possible. First, with no forces in Syria to support, a portion of the U.S. military presence in Jordan can be removed. Tower 22, a U.S. base that was the site of three U.S. fatalities in 2024, can be closed, and the number of forces located at Muwaffaq Salti Air Base in Jordan can be cut to around 1,000. Second, once the number of U.S. forces in Iraq has been reduced, the 13,500 personnel based in Kuwait can also be removed as they will no longer be needed to support or defend those deployed forward in Iraq. Given long-standing U.S. ties to Kuwait, this last move may be politically difficult, but the reality is that without troops in Iraq and with a much-reduced U.S. regional footprint, the logistical and support functions in Kuwait are not required.

Finally, Al-Udeid airbase should also be closed. While a small portion of the 10,000 personnel and aircraft currently located there might move elsewhere in the region, for example Prince Sultan airbase in Saudi Arabia, most would be returned stateside. After all, the recent air war between Israel and Iran has underscored the vulnerability of Al-Udeid when conflict occurs. Not only was it targeted by Iranian missiles, but most of its aircraft had to be moved elsewhere for their safety.39“Planes at Al Udeid Appear to Have Been Moved Before Iranian Missile Attack,” Wall Street Journal, June 23, 2024, https://www.wsj.com/livecoverage/iran-israel-us-latest-news/card/planes-at-al-udeid-appear-to-have-been-moved-before-iranian-missile-attack-wazFQ2BUZF1XjnveztJE?gaa_at=eafs&gaa_n=ASWzDAiamgPFOoMDBqGjToPfMc0eeA2Td6btVoL18A9HLue0pfok1CvU4R_eR39_vwk%3D&gaa_ts=686bfef9&gaa_sig=dsFQVcWIWa1no_xOX6GdMlljH5ZoVJZ1K2cHk2QJqPFOTVM8aH26MS65FoRqB-JBOiIjT56R3OZjNCrvPJ89QA%3D%3D. In total, these moves would remove close to 25,000 U.S. forces from the Middle East.

The second set of recommended changes would remove air and air defense assets surged to the Middle East after October 7. This would likely need to occur only after a more stable equilibrium was reached in the Middle East, given that additional air defense may be required to protect U.S. bases in the event that hostilities resume. But as soon as it’s practical, these assets should be returned to the United States for repair or redeployed to vulnerable U.S. locations in Asia and elsewhere.

Two fighter squadrons deployed as surge forces to the region are due to rotate out in the summer of 2025 and they should not be replaced. The United States should also remove the A-10 squadron deployed under President Biden and all other aircraft deployed to the region during the June 2025 surge as Israel launched its preventative war on Iran. This would cut the number of fighter and attack squadrons in the region to just two (also leaving reconnaissance and lethal drones positioned in the region).

The supporting forces for redeployed units, including about half the total air tankers and maintenance units currently in the region or at nearby bases, can also return home. Air defenses sent to the region after October 7, 2023 should also be removed. This would include the two THAADs based in Israel, since Israel has one of the most advanced and layered air defense systems in the world. The additional Patriot systems deployed across the region should either sent home or, for those that had been removed from South Korea, returned to Asia.

Changes should be made to U.S. naval power in the region. Departing from the practice of almost always keeping a CSG (or two) in the Persian Gulf or the Red Sea, we recommend that CSG deployments to the region be curtailed. Given limited U.S. interests in the Middle East, large deployments of naval power in the region serve little clear purpose. Evidence on whether naval presence deters is mixed at best, with costs typically outweighing benefits accrued.40Johnathan Panter, “Rolling Back Naval Forward Presence Will Strengthen American Deterrence,” War on the Rocks, February 20, 2025, https://warontherocks.com/2025/02/rolling-back-naval-forward-presence-will-strengthen-american-deterrence; Erik Gartzke and Jon R. Lindsay, Elements of Deterrence: Strategy, Technology, and Complexity in Global Politics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2024). At the very least, the United States faces few real threats likely to be deterred by a display of U.S. naval power. Iran’s nuclear program will remain a concern, but it is not clear that having an aircraft carrier floating off its coast affects Tehran’s calculus when it comes to nuclear enrichment. Moreover, with the U.S. little dependent on trade that runs through the Middle East, a constant U.S. naval presence is not required to secure U.S. economic interests.

This is also an instance where burden shifting makes sense. The United States has many partners in the region with their own robust naval forces, many armed with high-end U.S. weapons. It seems reasonable that after decades of U.S. support, they would take on more of the responsibility for the region’s maritime security, if such actions are warranted to support their own physical and economic security. They have little incentive to do this while the United States has a carrier nearby. In any case, U.S. destroyers from Rota could be moved into the Persian Gulf and CSGs themselves are highly mobile and could be moved into the region if the threat level necessitates it.

To replace the forces we recommend removing, we suggest keeping one conventionally armed Ohio-class submarine with Tomahawk cruise missiles in and around the Persian Gulf region as a deterrent and to respond to a crisis if required. The United States used the deployment of the USS Georgia in the fall of 2024 for this purpose.41Heather Mongilio, “USS Georgia Now in Middle East, Houthis Take Week-Long Pause on Ship Attacks,” USNI News, September 11, 2024, https://news.usni.org/2024/09/11/uss-georgia-now-in-middle-east-houthis-take-week-long-pause-on-ship-attacks. In the future, an Ohio-class submarine could serve as a relatively low-footprint way of signaling U.S. readiness to respond to attacks aimed at U.S. forces or harming U.S. interests in the Middle East.

Along with rotational deployments at Diego Garcia and the air and naval forces remaining in the UAE, Qatar, Bahrain, and Saudi Arabia, the United States would still have more than enough firepower and presence to react quickly to crises if required. This is still a sizeable U.S. military footprint in a region that is of limited direct importance to U.S. interests, so the posture recommended here should not be an endpoint, but rather the beginning of a longer drawing down of U.S. forces in the region.

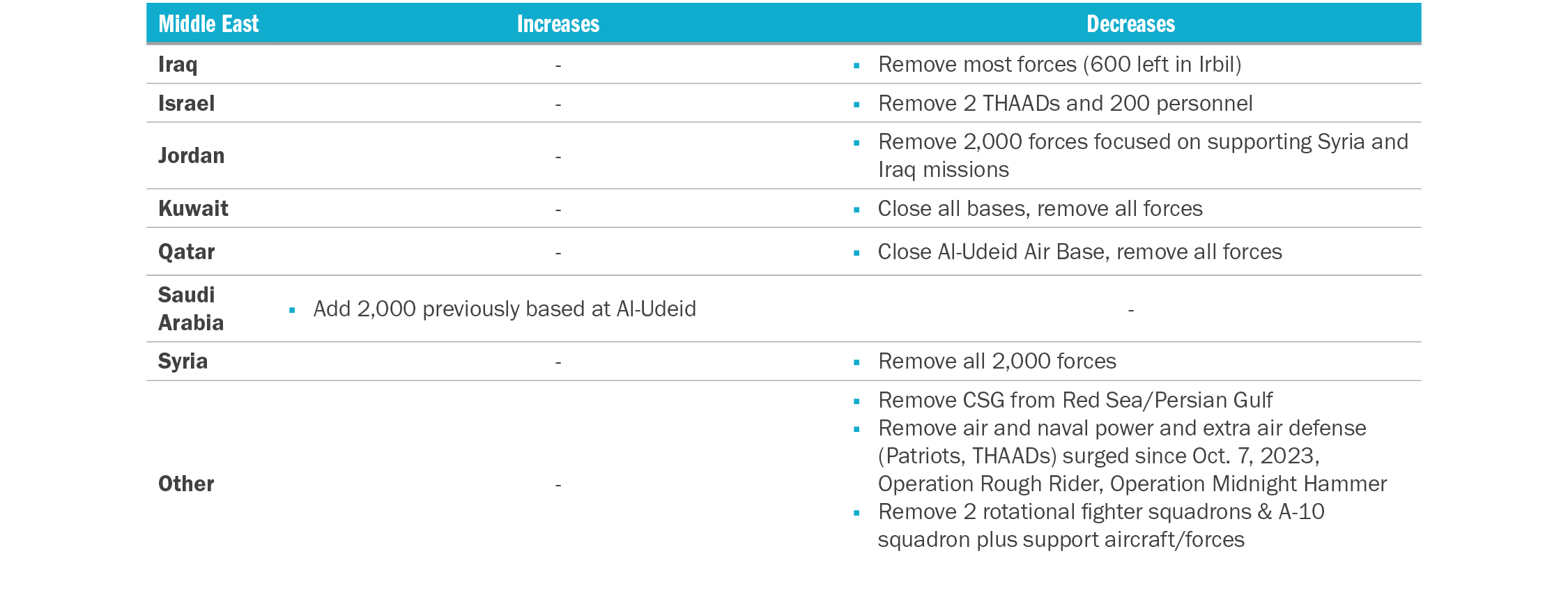

Overall, then, under our recommendations, the Middle East posture would change in the following ways:

- The removal of U.S. forces from Syria, Iraq, and Kuwait

- The reduction of the U.S. presence in Jordan to 1,000 troops

- The closure of the Al-Udeid airbase, with most forces returning to the United States and a small number (2,000 or so) moving to other bases in the region

- The removal of the rotational fighter squadrons deployed after the October 7 attacks plus their support units

- The curtailment of CSG deployments in Persian Gulf

- The removal of two THAADs from Israel and all additional Patriot battalions deployed in response to the October 7 attacks as part of Operation Rough Rider and in response to the Israel-Iran “12 Day War”

- The maintenance of a regular Ohio-class submarine deployment through the region

- The maintenance of a rotational presence at Diego Garcia and forces in Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, and UAE

- The final military footprint would be about a third as large as today’s forward presence and would be concentrated in a smaller number of countries and in locations where U.S. personnel can be adequately protected. Just as importantly, the recommended changes would allow for the redeployment of air and naval power and air defense assets that could serve important roles in an East Asian contingency.

Recommended posture changes: Middle East

Posture in Asia: Resilience and war prevention

Even those who would like to see a reduced U.S. military presence and role abroad generally agree that of all the global theaters, Asia is the region where the United States has the most significant interests at stake, and where the United States faces the fiercest competitor in China. Still, changes to the U.S. posture could help secure those interests more effectively and with less risk of unintended military escalation or entanglement in war.

Already the United States has a large military footprint in Asia. The United States stations about 28,500 personnel in South Korea, mostly soldiers and airmen; 55,000 personnel in Japan; a rotational presence in the Philippines that averages about 3,000 personnel; 500 military trainers on Taiwan; about 2,500 rotational personnel in Australia; and 9,700 personnel in Guam along with smaller numbers elsewhere along the second island chain. In addition, the Army has plans to deploy one MDTF to the region. There are five U.S. nuclear submarines based forward in Guam and one CSG homeported in Japan. There is typically one additional CSG operating in the Indo-Pacific as well. The United States also has an extensive fleet of aircraft in Asia, including eight U.S. Air Force fighter squadrons—four in Japan and four in South Korea (one of which is a “super squadron” of 31 aircraft)—a USMC F-35 squadron based at Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni, and the four F/A-18 squadrons associated with the CSG based in Japan.42Heather Mongilio, “USS Georgia Now in Middle East, Houthis Take Week-Long Pause on Ship Attacks,” USNI News, September 11, 2024, https://news.usni.org/2024/09/11/uss-georgia-now-in-middle-east-houthis-take-week-long-pause-on-ship-attacks. Rupert Schulenburg, “Reinforcement and Redistribution: Evolving US Posture in the Indo-Pacific,” International Institute for Strategic Studies, March 27, 2025, https://www.iiss.org/online-analysis/military-balance/2025/03/reinforcement-and-redistribution-evolving-us-posture-in-the-indo-pacific/; “Opening Remarks: Deterrence amid Rising Tensions,” May 15, 2025, FDD, 00:05:07, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NtjthjJPEAI; Luke A. Nicastro, U.S. Defense Infrastructure in the Indo-Pacific: Background and Issues for Congress, Congressional Research Service, R47589, June 6, 2023, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R47589; Clash Report (@clashreport), “The total number of American soldiers and military bases in Asisa/Pacific countries,” X, July 3, 2024, https://x.com/clashreport/status/1808522655089279175?lang=en; Enoch Wong, “US’ 500 Military Personnel in Taiwan an ‘Open Test’ of Beijing’s Red Lines,” South China Morning Post, May 26, 2025, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/military/article/3311807/us-500-military-personnel-taiwan-open-test-beijings-red-lines.

The problems with posture in Asia today

Some argue the current U.S. forward presence in Asia is too limited to effectively deter Chinese aggression or credibly prepare to defend U.S. allies. The more acute concern for those supportive of greater restraint in U.S. foreign policy is that today’s posture is too offensively oriented and located too close to China’s borders in places where U.S. personnel and assets are unlikely to survive in the event of a conflict and where they are more likely to provoke escalation than deter Chinese aggression.43Elbridge Colby, The Strategy of Denial: American Defense in an Age of Great Power Conflict (Yale University Press, 2021); Kurt M. Campbell and Jake Sullivan, “Competition without Catastrophe,” Foreign Affairs, August 1, 2019, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/competition-with-china-catastrophe-sullivan-campbell; Andrew Byers and J. Tedford Tyler, “Can the US and China Forge a Cold Peace?” Global Politics and Strategy 66, no. 6 (2024): 67–86, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00396338.2024.2432202; Jennifer Kavanagh and Stephen Wertheim, “The Taiwan Fixation: American Strategy Shouldn’t Hinge on an Unwinnable War,” Foreign Affairs, February 25, 2025, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/taiwan/taiwan-fixation-kavanagh-wertheim; Kelly A. Grieco and Jennifer Kavanagh, “America Can’t Surpass China’s Power in Asia,” Foreign Affairs, January 16, 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/america-cant-surpass-chinas-power-asia.

From this perspective, today’s U.S. military posture in Asia has a number of shortcomings. First, it pays too little attention to the risk of adversary balancing and escalation spirals. In recent years, the United States has surged more hard power into the Indo-Pacific region, close to Chinese shores, including the Typhon missile system in the Philippines and 500 trainers on Taiwan.44Seth Robson, “‘It Needs to be a Thousand’: US Has 500 Military Trainers on Taiwan, Retired Admiral Says,” Stars and Stripes, May 27, 2025, https://www.stripes.com/theaters/asia_pacific/2025-05-27/taiwan-military-trainers-testimony-17924124.html; Leilani Chavez, “US Typhon Missile System in Philippines Is a Subtle Headache for China,” Defense News, May 14, 2025, https://www.defensenews.com/global/asia-pacific/2025/05/14/us-typhon-missile-system-in-philippines-is-a-subtle-headache-for-china/. Rather than supporting deterrence, these moves drive China to more quickly balance or offset U.S. military moves. The end result is an arms race and heightened risk of war. Given the extremely high cost of any war with China, posture moves that are likely to drive escalation on the Chinese side should be considered carefully and generally avoided. Already China’s rapid military modernization has shifted the region’s military balance in its favor.

Second, the current U.S. posture is too heavily concentrated at a small number of locations, including many that would be highly vulnerable to Chinese missile attacks in the event of a conflict, for example southwestern Japan. While the U.S. military is already working to distribute this posture across more locations, constraints on U.S. military access and the limited willingness of regional partners to host U.S. ground forces or permit U.S. contingency operations from their territory pose a challenge, especially along the first island chain where the Pentagon has typically focused.45Harry Halem, “Distributed Maritime Operations, Logistics Industry, and American Strategy in Asia,” Military Strategy Magazine 10, no. 2 (2025): 43–52, https://www.militarystrategymagazine.com/article/distributed-maritime-operations-logistics-industry-and-american-strategy-in-asia/; Agile Combat Employment, U.S. Air Force, Air Force Doctrine Note 1–21 (2022), https://www.doctrine.af.mil/Portals/61/documents/AFDN_1-21/AFDN%201-21%20ACE.pdf. The United States will need to widen the scope of its search if it hopes to disperse its forces and increase their resilience and survivability.

Third, as in other theaters, free-riding by U.S. allies and partners remains a problem.46Rajan Menon and Daniel DePetris, “Allies Balancing: A Safer Strategy for the U.S. in Asia,” Defense Priorities, December 4, 2024, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/allies-balancing-a-safer-strategy-for-the-us-in-asia/; Robert E. Kelly, “Unintended Consequences of US Alliances in Asia,” Diplomat, April 7, 2014, https://thediplomat.com/2014/04/unintended-consequences-of-us-alliances-in-asia/. Although South Korea has spent more heavily on defense than many U.S. allies, it continues to depend on the United States for some key combat support capabilities. For Japan and the Philippines, relying on U.S. military support to ensure national security is Plan A, and according to some, there is no Plan B. For decades, Japan spent only 1 percent of its GDP on defense, confident that any shortfalls or gaps would be filled by the United States.

Taiwan, though not an official U.S. ally, has similarly come to assume that support from the United States in the event the island is attacked by China is more or less assured.47Fion Khan, “Taiwan Confident of US Support under Trump, Minister Says,” Taipei Times, May 2, 2025, https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2025/05/02/2003836216; Joyu Wang, “Taiwan’s New Strategy: Make China Fear the Pain of an Invasion,” Wall Street Journal, May 10, 2025, https://www.wsj.com/world/asia/taiwans-new-strategy-make-china-fear-the-pain-of-an-invasion-dfe28815. Though both Japan and Taiwan have increased their defense spending in recent years, neither has done enough given the security challenges each faces, and the United States has been too willing to carry the additional burden, sustaining a U.S.-centered regional security architecture that locks in U.S. dominance. This arrangement is both costly for the United States (especially as China’s military power grows) and risks pulling it into a war that does not advance its core interests.

Finally, current U.S. posture in Asia does not make sufficient use of the extensive defensive advantages the Indo-Pacific’s maritime theater offers, above and beyond the traditional advantages of defensive warfare. Japan, the Philippines, and to some extent even Taiwan are highly defensible using what is known as a “porcupine strategy,” oriented around naval and land mines, anti-ship missiles, air defense, and short-range artillery.48Eugene Gholz, Benjamin Friedman, and Enea Gjoza, “Defensive Defense: A Better Way to Protect US Allies in Asia,” Washington Quarterly 42, no. 4 (2020): 171–189, https://ndisc.nd.edu/assets/346572/gholzfriedmangjoza_42_4.pdf; Michael Beckley, “The Emerging Military Balance in East Asia: How China’s Neighbors Can Check Chinese Naval Expansion,” International Security 42, no. 2 (2017): 78–119, https://direct.mit.edu/isec/article/42/2/78/12177/The-Emerging-Military-Balance-in-East-Asia-How. Even if the United States offered limited or no support, China would find it very difficult to seize parts of Japan or the Philippines if either adopted this relatively cheap and attainable strategy, and with the right investments even Taiwan could make China think twice before attacking. Making better use of the advantages of defensive warfare in maritime environments with its posture investments and support to regional allies would allow the United States to reduce its regional footprint without weakening deterrence.

Principles to guide a revised U.S. posture in Asia

The shortcomings described above can be addressed by rebalancing U.S. posture in the Indo-Pacific, including by shifting the types and locations of forces.

A revised U.S. posture in Asia should be shaped by three principles. First, the United States should shift to allies and partners in the region primary responsibility for their own security, keeping the United States in support roles and where required guaranteeing core U.S. interests. Japan, the Philippines, Taiwan, and South Korea should be encouraged to work toward defense self-sufficiency at a rapid rate and the United States should adjust its military footprint to push countries in this direction.

In particular, the United States should increasingly concentrate its military investments in the region on combat support and enabling capabilities that can operate from standoff distances, leaving partners to put their own forces on the front line in any conflict. This would mean, for example, having Japanese forces take primary responsibility for the defense of Okinawa.

Second, the U.S. posture in Asia should exploit the advantages of defensive warfare, especially those associated with the region’s maritime environment. Leveraging a defense in depth strategy, the United States could operate largely from the second island chain by using stand-off weapons, long-range bombers, and submarines. To best exploit the region’s defensive opportunities, the United States should invest in hardening U.S. and allied ports, bases, and airfields; focus on maximizing the long-term survivability of assets based forward; and prioritize the deployment of air defense and other force protection capabilities into the theater.

Third, a revised U.S. posture in Asia should emphasize regional balancing, not dominance. Given China’s growing military power, it is increasingly unrealistic for the United States to maintain a position of hegemony in Asia. It is entirely plausible, however, for the United States to balance Chinese power and prevent it from gaining its own hegemonic position.49Grieco and Kavanagh, “America Can’t Surpass.” Doing so will require ensuring that at least Japan and likely the Philippines remain sovereign and outside of China’s orbit. The region’s geography makes both tasks achievable with strategic investments in U.S. posture at key locations in the region, including Northern Japan and the second island chain. A balancing approach does not require a direct U.S. military defense of Taiwan, however, as the tiny island would not dramatically shift the balance of power.50Kavanagh and Wertheim, “The Taiwan Fixation”; Michael D. Swaine, “Taiwan: Defending a Non-Vital US Interest,” Washington Quarterly 48, no.1 (2025): 165–185, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0163660X.2025.2478779.

Recommendations

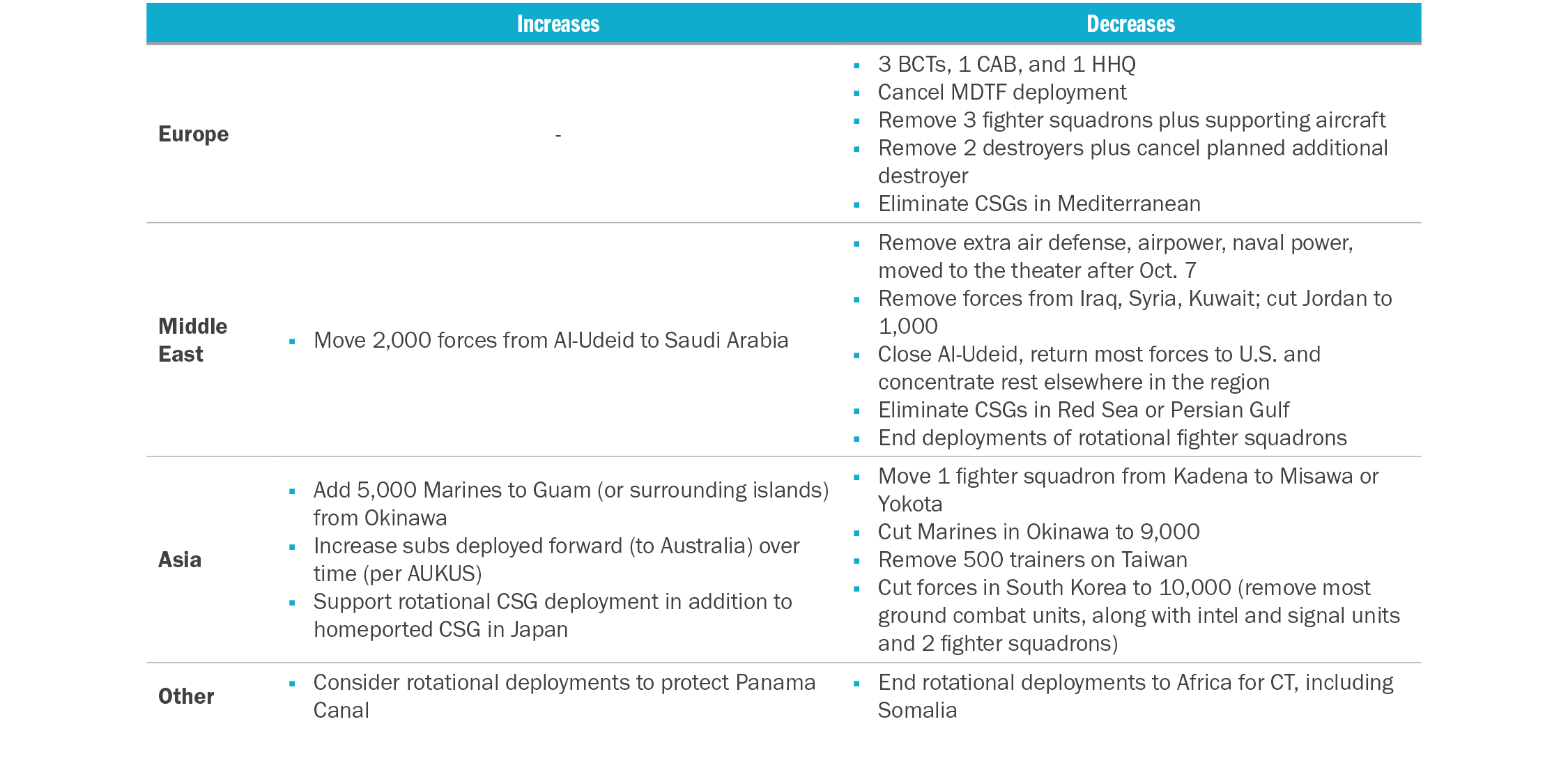

Overall, a revised U.S. military posture in Asia that adheres to the principles above would remove some U.S. forces from the theater and move others to new, more defensible locations, shifting substantial responsibility to allies and partners and moving the center of gravity of the U.S. regional posture from the first island chain to the second.

A revised U.S. posture in Asia would substantially reduce the number of U.S. forces deployed in South Korea, turning primary responsibility for the country’s self-defense back to Seoul. This is a reflection of both U.S. priorities and military capacity. As Elbridge Colby, now undersecretary of defense for policy, said in May 2024, “The fundamental fact is that North Korea is not a primary threat to the U.S.” As a result, going forward, in his view, “South Korea is going to have to take primary, essentially overwhelming responsibility for its own self-defense against North Korea because [the U.S. doesn’t] have a military that can fight North Korea and then be ready to fight China.”51Christian Davies, “The ‘Quiet’ Crisis Brewing between the US and South Korea,” Financial Times, May 26, 2025, https://www.ft.com/content/337ee9b3-208b-447c-9172-8e8f29f7d15d South Korea has a significant conventional military advantage over its neighbor to the north, and so should be able to effectively defend itself even without U.S. support, if not immediately then in the near term.

This being the case, it makes sense to downgrade the U.S. military footprint on the peninsula, including U.S. ground and air forces. This makes sense also because Seoul has not offered the United States unrestricted contingency access to use its bases for operations elsewhere in the theater during a conflict. Forces left in South Korea might be sidelined in the event of a regional war.

We recommend cutting all ground combat units not tied to base security from South Korea, along with Army signal, intelligence, and headquarters units, and some of their associated support and sustainment units. This would remove most of the 2nd Infantry Division from the peninsula, including the rotational BCT and Army combat aviation units. In addition, the United States should cut airpower based in South Korea, moving two fighter squadrons from U.S. bases in South Korea back to the United States. Along with the fighter aircraft, about a third of air maintenance and other support units and personnel can also be returned stateside.

In total, this would reduce the total U.S. military presence in South Korea by more than 50 percent, leaving about 10,000 personnel along with two fighter squadrons (including a larger super squadron) and support forces. The ground personnel left would be primarily for support, sustainment, logistics, and maintenance, leaving the responsibility for combat operations in the event of any crisis on the peninsula to South Korean forces. Eventually, the U.S. presence in South Korea should be reduced further, removing the remaining fighter aircraft and most ground forces, especially if South Korea continues to limit the U.S. ability to use defense assets in Korea to address other regional security crises. Some sustainment and maintenance personnel might remain if South Korea allows its bases to be used as logistics or repair hubs.

Moving to Japan, our recommendations focus primarily on increasing the survivability and resilience of U.S. forces and shifting most responsibility for front-line deterrence and defense to Japan itself. Of all the forces in Japan, it is those based in Okinawa that are the most politically sensitive and the most vulnerable in case of a conflict with China. With Okinawa just 500 miles from the Chinese coast, some experts argue that in the event of a war over Taiwan, Beijing would act quickly to attack U.S. bases located there to disable aircraft, destroy munitions, and crater available runways, with the aim of making it more difficult for the United States to intervene on Taiwan’s side. For this reason, there are questions about whether aircraft and other systems located on Okinawa would be able to contribute in the event of a war with China and, even if so, how much and over what timeframe.