Home / Grand strategy / Restraint: a post-COVID-19 U.S. national security strategy

May 29, 2020

Restraint: a post-COVID-19 U.S. national security strategy

Health and economic fallout from COVID-19 makes setting realistic defense priorities more urgent

- The response to the coronavirus global pandemic has severely weakened the U.S. economy, the foundation of national power. This reality has vast implications for U.S. foreign policy.

- Two economic factors suggest narrowing U.S. foreign policy objectives: (1) U.S. GDP and tax revenue will shrink in 2020, with no certainty about when they might recover. (2) Record deficits and debt endanger future economic growth.

- Political reasons for foreign policy restraint augment those economic factors: The public increasingly perceives non-security risks are paramount, and priority will go to domestic spending that aids recovery and increases domestic institutional resilience.

- Federal discretionary spending will bear a greater burden because mandatory spending programs are politically harder to cut. Since defense accounts for nearly half of discretionary spending, DoD will likely face sustained cuts.

- The U.S. enjoys a favorable geostrategic position with abundant protection from rivals, so it can cut defense spending without compromising security. Indeed, ending peripheral commitments in favor of core security interests strengthens the U.S.

- Ending policies bringing failure, overstretch, and drained coffers always made sense—coronavirus makes the case more urgent.

U.S. federal budget authority by category (FY 2019)

Declining GDP and tax revenue and increased domestic spending post-COVID-19 will put downward pressure on DoD budgets.

Abandon peripheral missions abroad and focus on core U.S. security and prosperity

- As the pandemic demonstrates, non-military threats can be far more detrimental to Americans’ well-being than the non-state actors, rogue states, and authoritarian regimes that dominate military planning and drive DoD spending.

- The decades-long pursuit of overly ambitious foreign policy goals disconnected from U.S. security contributed to the neglect of U.S. domestic institutions exposed by the coronavirus pandemic.

- Recovering requires investment at home: education, health care, infrastructure, research and development, and policies that promote innovation and job creation.

- For the past 20 years, the U.S. spent roughly $1 trillion annually on defense-related objectives (DoD, veteran’s care, homeland security, nuclear weapons, diplomacy) while domestic infrastructure in critical industries went under-resourced.

- Rebalancing defense priorities to focus more on economic prosperity and public health will enhance U.S. power in the long term.

Middle East: Reduce overinvestment and military presence, which has backfired and weakened the U.S.

- Core Middle East interests are (1) preventing significant disruptions to global oil supply and (2) defending against anti-U.S. terror threats. The former requires minimal U.S. effort; the latter requires intelligence, cooperation, and limited strikes, not occupations.

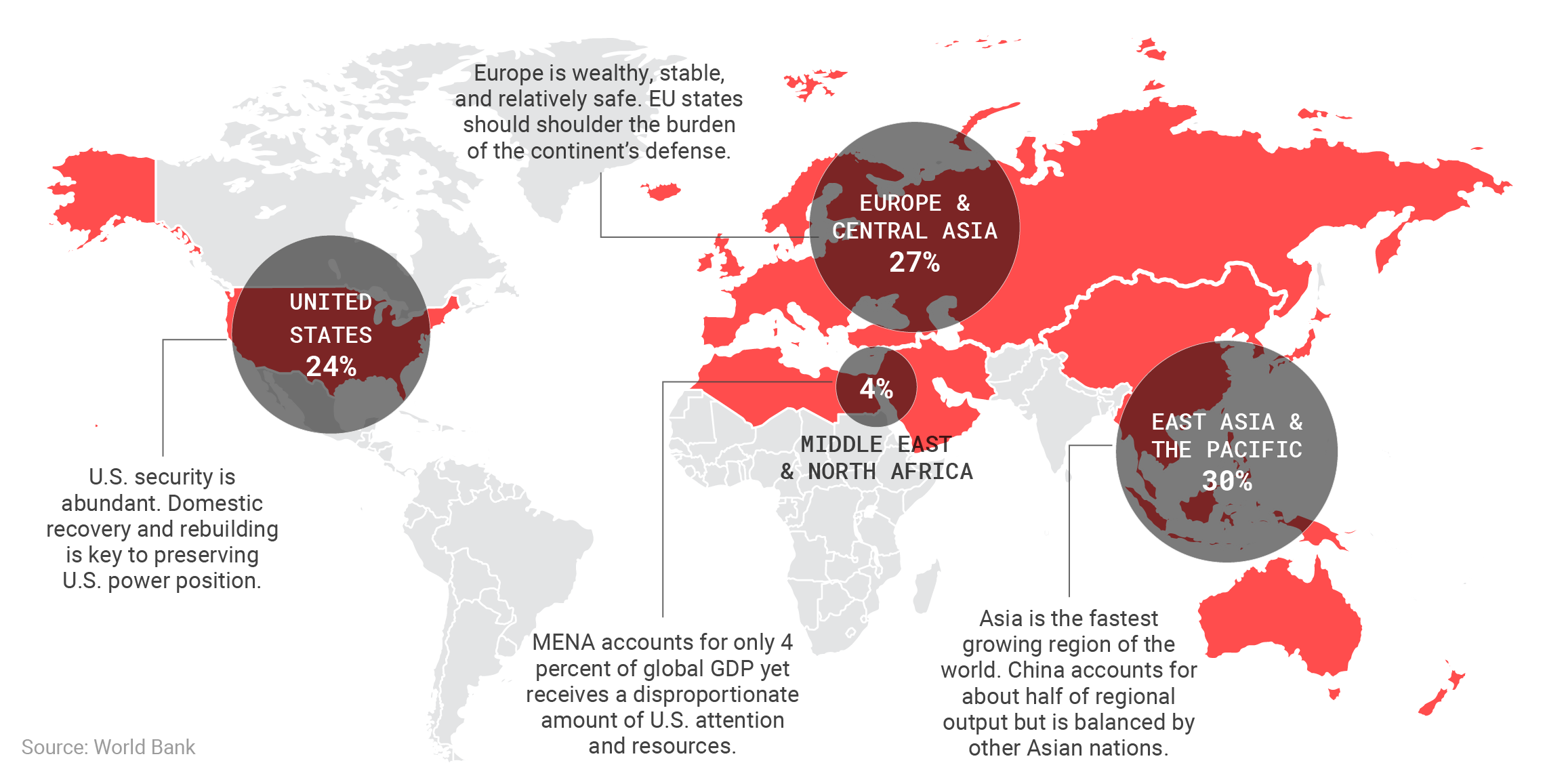

- The Middle East accounts for just 4 percent of global GDP, yet for decades, the U.S. has attempted to reshape the region through military force, disrupting the regional balance of power, exacerbating political instability, and allowing terrorist groups to flourish.

- Today, the U.S. has 62,000 troops in the region, many of them vulnerable to attacks by local militias. The U.S. is also fighting wars in Iraq, Syria, and Yemen, largely based on exaggerated fears of Iran, a middling power contained by its local rivals.1Miriam Berger, “Where U.S. Troops are in the Middle East and Afghanistan, Visualized,” Washington Post, January 4, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/where-us-troops-are-in-the-middle-east-and-could-now-be-a-target-visualized/2020/01/04/1a6233ee-2f3c-11ea-9b60-817cc18cf173_story.html.

- The U.S. will be able to fund part of its coronavirus recovery by ending its participation in conflicts in the Middle East and nearby areas, such as Afghanistan and Somalia. This would free up tens of billions of dollars annually for higher priorities.

- Additional savings can be had by focusing the Pentagon on its core warfighting missions and right-sizing force structurereducing ground forces in particular, which have been swollen by these commitments.

The U.S., Europe, and Asia account for 81 percent of global GDP

The U.S., Europe, and East Asia are the hubs of the global economy, making them more important to U.S. security and prosperity than the Middle East.

Europe: Shift security burdens to wealthy allies

- The U.S. has strong economic and diplomatic interests in Europe, but the continent faces limited direct military threats. Despite the fall of the USSR, the U.S. maintains a heavy military footprint in Europe in the name of securing wealthy, relatively safe allies.

- This arrangement served U.S. interests when a big U.S. military presence in Europe balanced the USSR’s military might while enabling allies to recover economically and unify.

- As allies grew rich and the USSR collapsed, a sensible balancing policy became a subsidy that let wealthy allies “cheap ride” on U.S. taxpayers, driving excess DoD spending while subsidizing lavish social welfare programs for European nations.

- Russia is a declining power (with a large nuclear arsenal). The EU dominates Russia in important metrics of national power: 3½:1 population, 11:1 GDP, and 5:1 military spending. European economies are also more dynamic than Russia’s.2The World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/; David Reid, “Europe’s Defense Spending Nears $300 Billion as Experts Say Trump’s Pressure is Paying Off,” CNBC, November 1, 2019, https://www.cnbc.com/2019/11/01/european-defense-spending-to-hit-300-billion-by-2021-analysts-say.html.

- Instead of jawboning allies for shirking their obligations, U.S. policy should shift the security burden onto them by (1) ending the European Defense Initiative and (2) implementing a responsible draw down of U.S. ground and nuclear forces on the continent.

- This would not only free up finite U.S. resources for higher priorities at home or in Asia, but also encourage European allies to revitalize their militaries: increasing spending, prioritizing modernization, or increasing military cooperation with each other.

Asia: Fortify Asian allies with A2/AD capabilities to deter Chinese aggression at less risk

- U.S. policy toward China—the only conceivable strategic competitor—balances several key interests: deterring Chinese territorial expansion against Asian allies, avoiding war, and ensuring a fair and beneficial trading relationship.

- Efforts to balance against China should therefore be based on core U.S. interests and carefully designed and planned to reduce cost, minimize escalation risks, and protect trade.

- U.S. goals in Asia are inherently defensive (to preserve the territorial status quo) and are best served by a military approach of “defensive defense”: an operational concept that limits U.S. costs by encouraging allies to develop their defensive capabilities.

- By improving anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) capabilities—a network of sensors and missiles—U.S. allies can deter Chinese attacks more effectively and cheaply than via investment in aircraft and surface ships that mimic U.S. capabilities.

- Allied defensive capability is less threatening to China than U.S. offensive capability. Reducing the perceived threat of direct attacks, A2/AD is less prone to spark costly, counterproductive arms racing.

- Pressing allies to adopt this approach will allow the U.S. to jettison escalatory plans to defend them by attacking the Chinese mainland, lowering tensions and risks of a broader war with China and allowing for cost saving on U.S. forces in Asia.

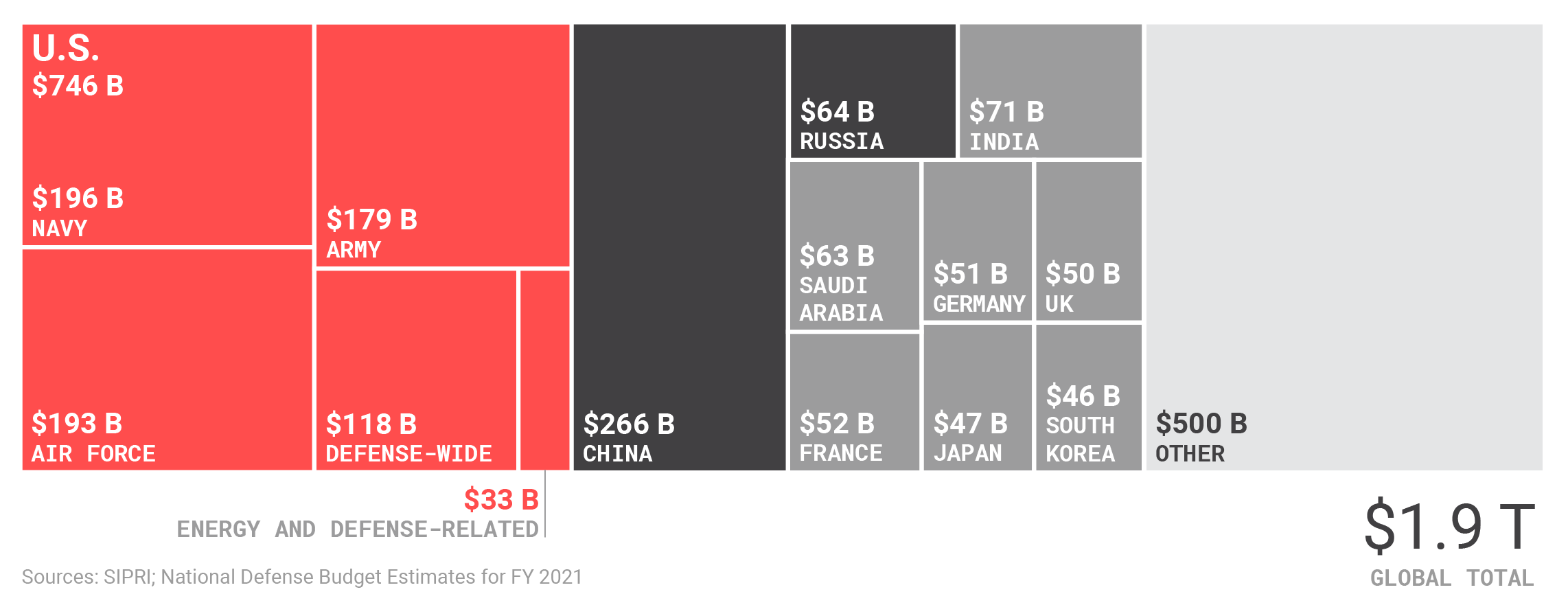

U.S. force structure: Constrained DoD budgets means more tradeoffs and rebalancing among the services

- With the world’s most sophisticated nuclear arsenal, large oceans separating it from rivals, and weak neighbors, the U.S. has a unique advantage over every other nation—security is abundant and cheap

- The U.S. accounts for 40 percent of global military spending—treaty allies account for 22 percent; Russia and China account for 17 percent.3“National Defense Budget Estimates for FY 2021,” Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), April 2020, https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/fy2021/FY21_Green_Book.pdf; “SIPRI Military Expenditure Database,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, https://www.sipri.org/databases/milex. The 2020 DoD budget ($757 billion) exceeds Cold War highs in real terms, reflecting a false sense of insecurity.

- Reduced DoD budgets can force debate and prioritization among programs and services—between what contributes to U.S. security and what is peripheral or even counterproductive—that large spending authorizations prevent.

- Geography makes the U.S. a natural naval power and trading nation. Distance from other major states means the U.S. is perceived as less threatening—unlike China, which borders other Eurasia powers.

- The Navy is the key service for projecting U.S. power globally and defending commerce if necessary while avoiding costly occupations. The Navy should command a larger portion of DoD’s reduced budget.

- With no nation building and a large reservist pool, the U.S. can reduce Army, Marines, and special operations forces end strength.

- Mission-driven reductions to force structure generate savings on personnel and procurement, enabling savings on operational costs, administrative overhead, basing, and other support functions.

U.S. military spending compared to allies and competitors

No major or regional powers are unscathed by the pandemic—strategic thinking will determine who comes out stronger

- The pandemic has hit all major powers hard, including U.S. adversaries; the economic pain is well distributed.

- China announced its GDP contracted at 6.8 percent in the first quarter of 2020, the first decline since 1976. The CCP relies on steady economic growth for legitimacy, and in a nation with almost no social safety net, job losses could breed discontent.

- While earning some goodwill, China’s efforts to help afflicted nations are an attempt to mitigate the reputational damage from its early obfuscation of the outbreak, which led to the global pandemic. Businesses are also taking steps to limit their China exposure.

- Record low oil prices could see Russia’s GDP fall by as much as 15 percent this year, resulting in more pressure to limit its military spending and interventions in places such as Ukraine and Syria.

- Iran has been crippled by the virus. Infection has killed several of its senior leaders, and the collapse in oil prices has damaged its already shrinking economy, making this middling power even weaker.

Foreign policy restraint enables long-term strength

- Strong fundamentals undergird U.S. power: favorable geography; a technologically advanced society with a skilled, innovative workforce; and abundant natural resources. Post-COVID rebuilding will require focusing on these strengths to restart the economy.

- The U.S. grew to become the global superpower by virtue of its productive economy; advanced technology, including nuclear weapons; and skillful diplomacy.

- The pursuit of liberal hegemony—militarized democracy spreading fueled by threat exaggeration and hubris—has resulted in strategic failure, military overstretch, and a hollowing out of U.S. internal strength.

- The coronavirus pandemic has exposed the extent to which U.S. power has been squandered. To recover its strength, U.S. should focus on the core elements of national power while avoiding excessive military projects and the overspending that entails.

- The budgetary demands to recover from this pandemic will be enormous, but the fundamental sources of U.S. security are robust—and insensitive to mild deviations in military activities and spending.

- Coronavirus is a terrible tragedy but nonetheless an opportunity to shed illusions and rebuild the real pillars of national strength for the long haul.

- As long as U.S. focuses on its prosperity—rather than peripheral distractions—it will grow stronger at home and retain the ability to marshal the resources necessary for competition with any adversary.

Endnotes

- 1Miriam Berger, “Where U.S. Troops are in the Middle East and Afghanistan, Visualized,” Washington Post, January 4, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/where-us-troops-are-in-the-middle-east-and-could-now-be-a-target-visualized/2020/01/04/1a6233ee-2f3c-11ea-9b60-817cc18cf173_story.html.

- 2The World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/; David Reid, “Europe’s Defense Spending Nears $300 Billion as Experts Say Trump’s Pressure is Paying Off,” CNBC, November 1, 2019, https://www.cnbc.com/2019/11/01/european-defense-spending-to-hit-300-billion-by-2021-analysts-say.html.

- 3“National Defense Budget Estimates for FY 2021,” Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), April 2020, https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/fy2021/FY21_Green_Book.pdf; “SIPRI Military Expenditure Database,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, https://www.sipri.org/databases/milex.

Events on Grand strategy

virtualSyria, Balance of power, Basing and force posture, Counterterrorism, Middle East, Military analysis

February 21, 2025