July 2, 2025

No GWOT-Narco

The perils of making war on cartels

Key points

- The violence perpetrated by Mexico’s drug cartels, their persistent export of drugs into the United States, and the massive toll of fentanyl overdose deaths have prompted the Trump administration to present U.S. military force as a possible solution.

- Any U.S. military incursion into Mexico will create more problems than it solves. It will disrupt the cartels for a time but drug smuggling will continue given demand and profits.

- U.S. military action could also raise the risk of the cartels retaliating against Americans inside Mexico and even inside the United States. The diplomatic repercussions would be significant as well: Mexico would view U.S. military force without its consent as an act of war.

- Various military solutions lack promise. A counterinsurgency operation will sink U.S. troops into a long-term campaign with no concrete end date. Targeting cartel kingpins is likely to splinter the cartels into smaller groups, not eliminate them. A plan to strengthen the presence of the Mexican military inside Mexico is also unlikely to work.

- There is no silver bullet to stop the cartels. While the United States can take some practical measures to weaken the cartels, like stemming the flow of firearms into Mexico, it can’t achieve much more than this and shouldn’t try.

Military force inside Mexico: A self-fulfilling prophecy

Amid the ongoing drug crisis in the United States, the Trump administration has reportedly been mulling using military force inside Mexico to weaken the cartels and stem the tide of drugs coming into the U.S. But making the war on drugs literal will not work. U.S. military action cannot arrest the flows of fentanyl or other drugs, but it can make things worse inside Mexico and present new risks to the United States.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that about 79,000 Americans died of a drug overdose in 2024.1“Provisional Drug Overdose Data,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, May 15, 2025, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm. While this figure represents a 27 percent decline from the prior year, drug overdoses remain the leading cause of death among Americans ages 18–44.2“Statement from CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control on Provisional 2024 Overdose Death Data,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, May 14, 2025, https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2025/2025-statement-from-cdcs-national-center-for-injury-prevention-and-control-on-provisional-2024.html. Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is both easy to produce and 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine, continues to ravage communities across the United States.

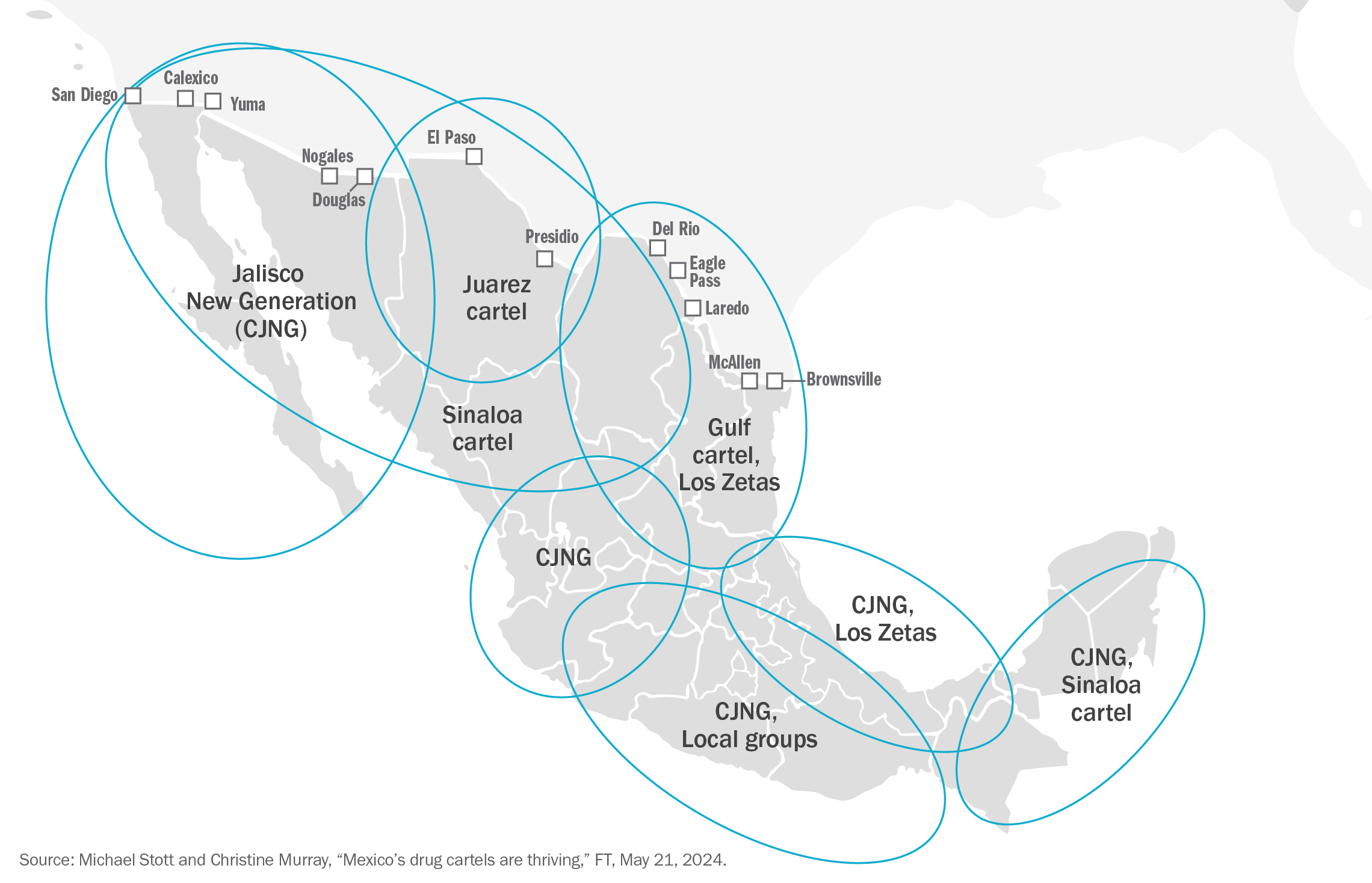

Mexico’s two largest criminal organizations, the gradually fracturing Sinaloa Cartel and Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG), produce and ship most of the fentanyl that arrives into the United States, mainly through legal ports of entry. According to the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), both cartels “control clandestine production sites in Mexico, smuggling routes into the United States, and distribution hubs in key U.S. cities,” and have a presence in nearly every U.S. state.3“National Drug Threat Assessment 2025,” Drug Enforcement Administration (May 2025), 5, 7,10, https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2025-05/2025%20National%20Drug%20Threat%20Assessment_Web%205-12-2025.pdf.

While exact figures are hard to come by, it’s reasonable to think Mexican cartels earn billions of dollars every year from the drug trade, which can be used to purchase firearms, bribe public and law enforcement officials, expand their manufacturing base, and recruit sicarios into their ranks.4Salvador Rizzo, “Do Mexican drug cartels make $500 billion a year?” Washington Post, June 24, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/06/24/do-mexican-drug-cartels-make-billion-year/. One study assessed that the cartels have become so economically important in Mexico that they represent the country’s fifth-largest employer, with 350–370 people joining every week.5Rafael Prieto-Curiel, Gian Maria Campedelli, and Alejandro Hope, “Reducing Cartel Recruitment Is the Only Way to Lower Violence in Mexico,” Science 381, no. 6664 (September 21, 2023): 1312–1316, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adh2888.

Successive U.S. administrations have sought to counter Mexico’s cartels by degrading their military capacity, undermining their revenue streams through sanctions, freezing their assets, prosecuting cartel members, and boosting the power of the Mexican government to conduct counter-narcotics operations. Yet President Donald Trump has long viewed these policies as failures. On multiple occasions, Trump has threatened to deploy the U.S. military to Mexican soil to combat the cartels, either by launching targeted airstrikes or by deploying U.S. special operations forces.6Mark Esper, one of Trump’s defense secretaries during his first term, writes in his memoir that Trump inquired whether the United States should shoot missiles into Mexico to destroy fentanyl labs, a request Esper advised against. Maggie Haberman, “Trump Proposed Launching Missiles Into Mexico to ‘Destroy the Drug Labs,’ Esper Says,” New York Times, May 5, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/05/us/politics/mark-esper-book-trump.html; Mark T. Esper, A Sacred Oath: Memoirs of a Secretary of Defense During Extraordinary Times (New York: HarperCollins, 2022). During his March 6 address to Congress, Trump declared that the United States was now waging war on the cartels just as the cartels have waged war on the United States. “Remarks by President Trump in Joint Session of Congress,” White House, March 4, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/remarks/2025/03/remarks-by-president-trump-in-joint-address-to-congress/. A month later, during an April 2025 call with Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum, Trump reportedly recommended having the U.S. military take the lead role in counter-narcotics operations on Mexican soil. Sheinbaum denied the request. José de Córdoba and Santiago Perez, “Trump, Mexico’s Sheinbaum Spar Over Drug Cartels,” Wall Street Journal, May 2, 2025, https://www.wsj.com/world/americas/trump-mexicos-sheinbaum-spar-over-drug-cartels-f3aae16c. Trump’s second administration is staffed with senior officials who have either sympathized with this course of action or supported it outright, including former national security adviser Mike Waltz, Vice President J.D. Vance, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth, and U.S. Ambassador to Mexico Ronald Johnson.7“H.J Res 18, AUMF Cartel Influence Resolution,” U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, January 12, 2023, https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-joint-resolution/18/text; Charles Borla, “JD Vance in Tucson: Send in U.S. military ‘to battle with the Mexican drug cartels,’” Arizona Daily Star, October 22, 2024, https://tucson.com/news/local/government-politics/elections/tucson-rally-sen-jd-vance-gop-vp-candidate-border-cartels-military/article_661ef4e6-8d80-11ef-bb8e-1747a0dcaa25.html; José de Córdoba, Santiago Perez, and Vera Bergengruen, “Hegseth Warned of Military Action if Mexico Fails to Meet Trump’s Border Demands,” Wall Street Journal, February 28, 2025, https://www.wsj.com/politics/policy/trump-mexico-drug-cartel-tariff-hegseth-military-action-5f507ab0; Avery Lotz, “Mexican ambassador pick won’t rule out military strikes on cartels,” Axios, March 13, 2025, https://www.axios.com/2025/03/13/trump-mexico-ambassador-cartels-military-drone-strikes.

The Trump administration appears to believe that the “total elimination” of the cartels, in Attorney General Pam Bondi’s words, is not only a realistic objective but necessary to halt the traffic of fentanyl into the United States.8“Total Elimination of Cartels and Transnational Criminal Organizations,” U.S. Department of Justice, February 5, 2025, https://www.justice.gov/ag/media/1388546/dl?inline. On the first day of his second term in office, Trump signed an executive order declaring a national emergency along the U.S.-Mexico border and initiated a process to designate the Mexican cartels as foreign terrorist organizations (FTOs).9“Declaring a National Emergency at the Southern Border of the United States,” White House, January 20, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/declaring-a-national-emergency-at-the-southern-border-of-the-united-states/; “Designating Cartels and Other Organizations As Foreign Terrorist Organizations and Specially Designated Global Terrorists,” White House, January 20, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/designating-cartels-and-other-organizations-as-foreign-terrorist-organizations-and-specially-designated-global-terrorists/. The State Department officially listed six Mexican cartels as FTOs a month later. “Designation of International Cartels,” U.S. State Department, February 20, 2025, https://www.state.gov/designation-of-international-cartels/. The Defense Department’s interim policy guidance directed the U.S. military to embrace a more assertive role in countering drug trafficking.10Alex Horton and Hannah Natanson, “Secret Pentagon memo on China, homeland has Heritage fingerprints,” Washington Post, March 29, 2025, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/2025/03/29/secret-pentagon-memo-hegseth-heritage-foundation-china/. And in collaboration with Mexico, the CIA has authorized more U.S. surveillance flights over cartel-dominated areas.11Julian E. Barnes, Marie Abi-Habib, Edward Wong, and Eric Schmitt, “C.I.A. Expands Secret Drone Flights Over Mexico,” New York Times, February 18, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/02/18/us/politics/cia-drone-flights-mexico.html.

Yet as this paper argues, treating Mexican cartels in the same vein as the Islamic State or al-Qaeda risks creating a self-fulfilling prophecy—a cartel landscape inside Mexico that is more dangerous, fragmented, and difficult to combat while offering virtually no hope of disrupting drug flows enough to impact U.S. consumption. Military options will be ineffective at preventing or deterring the cartels from shipping drugs to the large U.S. market. As they have in the past, narcotrafficking networks will adapt rather than terminate a revenue stream that has proven to be highly profitable for them.

At best, U.S. military strikes in Mexico will weaken the cartels over the short term. At worst, they will cause the cartels to splinter even further, spiking the level of violence, straining the Mexican government’s military resources, and causing significant blowback against Americans in both Mexico and the United States. Unilateral military action will also complicate, if not end, the security coordination the United States and Mexico have built over the last two decades. Cooperation on other issues such as slowing migration, a top Trump administration priority, could also be harmed, particularly if the United States conducts military operations inside Mexico without its consent.

This paper will show why further militarizing the war on drugs holds far more costs than benefits for the United States. After chronicling a short history of Mexico’s struggles with cartel-orchestrated violence, it will detail the risk associated with a military-centric strategy. Finally, it will offer several more realistic—if decidedly less sexy—recommendations that aim to weaken the cartels and mitigate the havoc they can wreak.

Mexico’s failed war on drugs

Drug cultivation and trafficking is not a new problem in Mexico. In the 1950s and 1960s, marijuana production in the so-called Golden Triangle region of Chihuahua, Durango, and Sinaloa was prevalent. Mexico was a waystation for the Colombian cocaine trade during the 1970s and 1980s, when Colombian traffickers used Mexican smugglers to send their products into the United States.12“The Medellín Cartel’s Future,” Drug Enforcement Administration, March 28, 1994, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/document/28748-document-13-pepes-annex-document-10-march-28-1994.

Mexico, under the long one-party rule of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), largely managed Mexican narcotrafficking organizations with a carrot rather than a stick. In exchange for a cut of the proceeds and a commitment not to sell drugs inside Mexico, lower to mid-ranking Mexican government officials essentially looked the other way.13Mónica Serrano, “States of Violence: State-Crime Relations in Mexico,” in W.G. Pansters, Violence, Coercion and State-Making in Twentieth-Century Mexico: The Other Half of the Centaur (Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press, 2012), 135–158. Traffickers who violated the terms of the agreement were met with more scrutiny from law enforcement. Over time, the Mexican state became a mediator whenever intra-cartel disputes erupted.14Viridiana Rios, “How government coordination controlled organized crime: The case of Mexico’s cocaine markets,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 59, no. 8 (2015): 1433–1454. Although morally dubious, this arrangement allowed the Mexican state a degree of control over cartel operations, keeping the level of violence in Mexico low.

This model, however, broke down as Mexico transitioned from the PRI-dominated political system into a multi-party democracy at the turn of the millennium. Drug traffickers who previously understood the rules of the game now had to adapt to the new political system. The election in 2000 of Vicente Fox, the first non-PRI president in seven decades, was an opportunity for the cartels to distance themselves from the old system of government-imposed restrictions that had restrained their operations on Mexican soil.15Shannon O’Neil, ”The Real War in Mexico,” Foreign Affairs 88, no. 4 (2009): 63–77, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/mexico/2009-07-01/real-war-mexico. Fox’s six-year presidency witnessed a surge in high-profile incidents of violence targeting civilians in large cities like Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez as cartels fought over smuggling routes and sought to consolidate territorial control over new terrain. This raised concerns that the Mexican state had lost its capacity to manage the problem.16Jorge Castañeda, “Mexico’s Failed Drug War,” Cato Institute, May 6, 2010, https://www.cato.org/economic-development-bulletin/mexicos-failed-drug-war; Jo Tuckman, “Mexican drug cartels battle for power,” Guardian, February 1, 2004, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2004/feb/02/mexico.

Confronted with heightened violence, President Felipe Calderón (2006–2012) declared war on the cartels shortly after assuming office. Tens of thousands of Mexican troops were deployed to the most troubled regions of the country with orders to kill or arrest top cartel leaders, eliminate their revenue sources, staff checkpoints, and patrol streets. But the strategy merely worsened the problem. Drug violence soared to unprecedented levels.17David A. Shirk, “The Drug War in Mexico,” no. 60, Council on Foreign Relations, March 2011, https://www.cfr.org/report/drug-war-mexico. The cartels fought back with increasingly gruesome attacks against police officers, politicians, and civilians.

Mexican army raids that took out top cartel operatives also created power vacuums within the targeted organizations, spiking violence further as replacements fought each other to attain control. The Mexican army had little help from local and state police officers, some of whom had been bought off by the cartels. Mexican army abuses spiked. By the end of Calderón’s presidency, more than 100,000 people had been killed.18Daniel Hernandez, “Calderon’s war on drug cartels: A legacy of blood and tragedy,” Los Angeles Times, December 1, 2012, https://www.latimes.com/world/la-xpm-2012-dec-01-la-fg-wn-mexico-calderon-cartels-20121130-story.html.

Calderón’s successor, Enrique Peña Nieto (2012–2018), pledged a total revamp of a military-centric strategy he argued had failed to weaken the cartels. His security plan centered on reforming Mexico’s notoriously slow judicial system, instituting a new training regime for police recruits, and prioritizing violence reduction over drug seizures.19“Peña Nieto’s Challenge: Criminal Cartels and Rule of Law in Mexico,” International Crisis Group, no. 48, March 19, 2013, https://www.crisisgroup.org/latin-america-caribbean/mexico/pena-nieto-s-challenge-criminal-cartels-and-rule-law-mexico. However, as his term progressed, Peña Nieto would come to rely on the same military tools and tactics he denounced when he was a candidate.20Patrick Corcoran, “A Legacy of Turmoil: Peña Nieto’s Tenure in Mexico,” Insight Crime, November 27, 2018, https://insightcrime.org/news/legacy-pena-nieto-mexico/; Elisabeth Malkin, “Mexico Strengthens Military’s Role in Drug War, Outraging Critics,” New York Times, December 15, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/15/world/americas/mexico-strengthens-militarys-role-in-drug-war-outraging-critics.html. More than 33,000 people were killed during Peña Nieto’s final year in office.21June S. Beittel, “Mexico: Organized Crime and Drug Trafficking Organizations,” R41576, Congressional Research Service, June 7, 2022, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R41576.

By the time Andrés Manuel López Obrador (2018–2024) was sworn in, Mexico’s homicide rate was at an all-time high. In contrast to Calderón and Peña Nieto, AMLO, as he was known, initially sought to address the root causes of crime and drug trafficking through his “abrazos, no balazos”—“hugs, not bullets”—strategy. This centered on providing better education and job programs to Mexican youth to dissuade them from joining criminal groups. State-funded scholarships and job training stipends were handed out to more than two million young people during AMLO’s first year in a bid to starve cartel recruitment.22David Shirk, “AMLO, Violent Crime, and Public Security in Mexico,” Wilson Center, November 30, 2019, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/amlo-violent-crime-and-public-security-mexico.

Yet these socioeconomic programs take a long time to work, if they work at all, and Mexico did not have the luxury of time. AMLO, who campaigned on bringing Mexican troops back to the barracks, would go on to do precisely the opposite. He deployed the army on show-of-force missions that were more symbolic than substantive and created the National Guard, an ostensibly civilian institution that was staffed by former soldiers and commanded by former military officers.23Jared Olson, “How AMLO Has Fueled Mexico’s Drug War,” Foreign Policy, June 23, 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/06/23/mexico-drug-war-amlo-lopez-obrador-demilitarization-national-guard-human-rights/. None of it made a tangible difference. Proceso, a Mexican newspaper, registered nearly 200,000 homicides during AMLO’s tenure, an increase of more than 25 percent over the previous six-year period.24Rafael Croda, “AMLO’s six-year term exceeded 34.7% that of Peña Nieto in gun homicides,” Proceso, March 4, 2025, https://www.proceso.com.mx/nacional/2025/3/4/el-sexenio-de-amlo-supero-347-al-de-pena-nieto-en-homicidios-con-arma-de-fuego-346658.html.

Military action against the cartels is a losing strategy

Over the last quarter-century, security in Mexico has deteriorated as the cartels have strengthened in capability and numbers. When the Sinaloa and Jalisco New Generation Cartels are not fighting each other for territory, they are fighting the Mexican army, whose responsibility for public security and counternarcotics has risen over the last three Mexican administrations. In some parts of Mexico, the cartels are the de facto authority, settling disputes, establishing informal tax regimes on businesses, and even distributing healthcare.25Vanda Felbab-Brown, “How the Sinaloa Cartel Rules,” Brookings Institution, April 4, 2022, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/how-the-sinaloa-cartel-rules/; José de Córdoba, “Mexico’s Cartels Distribute Coronavirus Aid to Win Popular Support,” Wall Street Journal, May 14, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/mexicos-cartels-distribute-coronavirus-aid-to-win-popular-support-11589480979. General Glen VanHerck, the former commander of U.S. Northern Command, assessed in 2021 that as much as 35 percent of Mexico is ungoverned by or even inaccessible to the Mexican state, although this could be an overstatement.26General Glen Vanherck, “USNORTHCOM-USSOUTHCOM Commander’s Joint Press Briefing Remarks,” U.S. Northern Command, March 16, 2021, https://www.northcom.mil/Newsroom/Transcripts/Transcript/Article/2542592/usnorthcom-ussouthcom-commanders-joint-press-briefing-remarks/.

Given these facts, Donald Trump is correct in thinking the situation in Mexico is dire. But the military action that he and so many in his administration support will only make this troubled situation worse. There are no good U.S. military options to mitigate these problems. As explained below, all the possible options—a counterinsurgency strategy similar to what the U.S. military performed in Iraq and Afghanistan, a decapitation approach where high-profile narcotraffickers are targeted, striking fentanyl labs from the air, and transferring more military equipment and tactical-level support to the Mexican security forces—would do little to mitigate the cartels’ influence and could backfire on the United States.

COIN in Mexico

As the cartels have become wealthier and more powerful, some U.S. politicians have argued that the United States and Mexico need to adopt a far more proactive, aggressive approach to the problem. Such an approach would treat narcotrafficking organizations as insurgencies rather than criminal networks. In 2010, then-secretary of state Hillary Clinton stated that “these drug cartels are now showing more and more indices of insurgency.”27“A Conversation with U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton,” interviewed by Richard Haass, Council on Foreign Relations, September 8, 2010, https://www.cfr.org/event/conversation-us-secretary-state-hillary-rodham-clinton-2. Congressman Dan Crenshaw, the chairman of the House Select Committee to Defeat Drug Cartels, made a similar assertion in January 2025, writing that “[t]he cartels are an insurgency—mixing organized crime, terrorist acts, and occasional false benevolence to keep the population under control.”28Dan Crenshaw (@dancrenshawtx), “The cartels are an insurgency – mixing organized crime, terrorist acts, and occasional false benevolence to keep the population under control,” Instagram, January 2, 2025, https://www.instagram.com/dancrenshawtx/p/DEVTAD3zuO5/?img_index=1.

Defining the cartels as an insurgency implies that a counterinsurgency strategy is the best way to combat them. Although past counterinsurgency campaigns—Britain’s 1948–1960 operation in Malaya and Russia’s war in Chechnya during the late 1990s to early 2000s, to name two—often involved the extreme coercion of civilians, the United States has opted for a “winning hearts and minds” approach in order to delegitimize insurgents in the eyes of the population.29Paul Dixon, “Hearts and Minds? British Counter-Insurgency from Malaya to Iraq,” Journal of Strategic Studies 32, no. 3: 353–381, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/01402390902928172.

The recent U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan suggest that a hypothetical U.S. counterinsurgency strategy in Mexico would entail a similar population-centric approach, where security and improved services were coupled with military force to undercut popular support for the cartels. It would likely involve a heavy presence of U.S. and Mexican forces across the regions where the cartels operate, combined with U.S. assistance to Mexico’s diplomatic, economic, and developmental efforts to win over the population, cut off the insurgency’s revenue sources, and enhance the state’s authority.30Previous counterinsurgency campaigns have often been brutal, repressive, and extremely violent. As Jacqueline Hazelton writes in her book Bullets Not Ballots, there have been numerous cases where the state chose to exploit its advantages in military power to coerce rather than persuade the population into rejecting anti-state forces. Jacqueline L. Hazelton, Bullets not Ballots: Success in Counterinsurgency Warfare (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2021).

Drug cartel activity in Mexico (2021)

Yet as the U.S. military learned most recently in Iraq and Afghanistan, counterinsurgency, or COIN for short, is a difficult strategy to successfully implement in the most optimal circumstances. COIN tends to take a long time to show progress, is resource-intensive, requires a degree of local knowledge and patience outsiders often lack, and must rely on a host government willing and able to reform itself. According to the Rand Corporation, the median length of a successful counterinsurgency is 11 years.31Christopher Paul, Colin P. Clarke, Beth Grill, and Molly Dunigan, “Paths to Victory: Detailed Insurgency Case Studies,” RAND, September 26, 2013, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR291z2.html. The same study suggests that a counterinsurgency victory rests on three main factors: diminishing an insurgency’s tangible support and ability to recruit; exhibiting long-term motivation to defeat the insurgents; and adapting when the insurgents change tactics.32Christopher Paul et al, “Paths to Victory.”

In Mexico’s case, employing population-centric counterinsurgency is especially unpromising for two main reasons. First, the cartels do not rely on popular support the way most political insurgencies do, depending instead on drug revenue. Due to the profitability of the drug business and the lack of viable economic alternatives in many of the areas where the cartels operate, there will always be a stream of recruits ready to join these criminal organizations as well as the resources to purchase the necessary weapons.

Unfortunately for the Mexican government, those resources are near-endless for the cartels. At its peak in 2014, ISIS reportedly made between $1 million to $3 million a day by selling oil and captured antiquities on the black market as well as through extortion and taxation.33Ana Swanson, “How the Islamic State makes its money,” Washington Post, November 18, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2015/11/18/how-isis-makes-its-money/. By contrast, in 2021, the Mexican cartels might have earned as much as $13 billion from human smuggling alone.34“Causes, Costs, and Consequences,” U.S. House Committee on Homeland Security, July 14, 2023, https://homeland.house.gov/2023/06/14/chairman-green-homeland-security-members-announce-release-of-preliminary-report-on-secretary-mayorkas-dereliction-of-duty/. The cartels pocket many billions more from the fentanyl trade, which due to its low processing costs and high rates of return has proven to be a durable financial source.35“The Expansion and Diversification of Mexican Cartels: Dynamic New Actors and Markets,” in The Armed Conflict Survey 2024, International Institute for Strategic Studies, December 12, 2024, https://www.iiss.org/publications/armed-conflict-survey/2024/the-expansion-and-diversification-of-mexican-cartels-dynamic-new-actors-and-markets/. These profits not only purchase loyalty but attract would-be recruits looking for a quick payday.

Second, even if a COIN strategy was relevant in Mexico’s case, prosecuting such a campaign would run into significant problems. The scale of cartel operations in Mexico, as well as the inadequacies of the Mexican government, make successful implementation a highly doubtful prospect.

Including national guard troops, approximately 370,000 personnel in the Mexican security forces are responsible for securing a country of more than 130 million people.36“Mexico,” CIA World Factbook, updated June 25, 2025, https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/mexico/#military-and-security. Most of those personnel are already tied down with public security, counternarcotics operations, constructing large-scale infrastructure projects, administering airports, and other varied tasks.

Flooding cartel-infested regions with troops for clearing operations, and holding this territory to ensure long-term stability, would require a significant rise in Mexico’s military budget. Given the systemic weaknesses of the Mexican economy, a big infusion of cash is fiscally unsustainable unless the Mexican government takes on more debt or reduces spending on entitlements and domestic benefits, which would be politically unpopular. Even after a 39 percent increase in defense spending between 2023 and 2024, Mexico’s defense budget is only $16.7 billion—less than 1 percent of gross domestic product, among the lowest in the Western Hemisphere.37Xiao Liang et al, “Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2024,” SIPRI, April 2025, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2025-04/2504_fs_milex_2024.pdf. To make counterinsurgency remotely feasible, the United States would have to pay for the Mexican army’s expansion or provide forces to aid it.

It is hard to imagine the Trump White House or any other administration adopting the latter course given the experience with counterinsurgency operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, which ended in failure despite enormous costs in U.S. blood and treasure. But if the United States did order U.S. troops to join a military and policing effort against the cartels, it would at best be a short-term holding pattern without a host government or local authority willing and able to attack the backing of these criminal groups. The United States was unable to make this work in Afghanistan or Iraq, whose ruling elites had incentives to reject or slow down major changes to preserve their own power.38“Remarks Prepared for Delivery by Special Inspector General John F. Sopko on the release of SIGAR’s first lessons learned report, ‘Corruption in Conflict: Lessons from the U.S. Experience in Afghanistan,’” Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, September 14, 2016, https://www.sigar.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/4018819/remarks-prepared-for-delivery-by-special-inspector-general-john-f-sopko-on-the/. In Iraq, after U.S. troops withdrew in 2011, the government in Baghdad resorted to marginalizing the Sunni community rather than incorporating it into the national government, aiding the rise of ISIS three years later. If local elites profit from the status quo, then no amount of foreign military investment will cause them to change course.39Benjamin H. Friedman, Harvey M. Sapolsky, and Christopher Preble, “Learning the Right Lessons from Iraq,” Policy Analysis no. 610, Cato Institute, February 13, 2008, https://www.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/pubs/pdf/pa-610.pdf.

Corruption exists at all levels of the Mexican political system, from the police officer on the street to the politician in a high office. Flush with cash, the cartels have successfully co-opted state officials and police commanders. Examples of state officials colluding with the cartels are many, and most of them are eventually prosecuted by the United States, not Mexico.40There are other examples as well. In 2013, the former governor of the Mexican state of Quintana Roo was sentenced to a decade in prison for protecting drug shipments bound for the United States in return for bribes. “Former Governor Of Mexican State Sentenced In Manhattan Federal Court To 131 Months In Prison For Money Laundering In Connection With Narcotics Bribes,” U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York, June 28, 2013, https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdny/pr/former-governor-mexican-state-sentenced-manhattan-federal-court-131-months-prison-money. In 2022, a former Mexican federal police officer was given 10 years in prison for a similar offense. “Former Mexican Federal Police Commander Sentenced to 10 Years’ Imprisonment for Drug Trafficking Conspiracy,” U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of New York, February 9, 2022, https://www.justice.gov/usao-edny/pr/former-mexican-federal-police-commander-sentenced-10-years-imprisonment-drug. The most notorious of these cases was that of Genaro Garcia Luna, the former secretary of public security and point man in President Calderón’s war against the cartels. Luna was convicted by a U.S. jury in 2023 on charges of international cocaine distribution and conspiracy to import cocaine.41“Ex-Mexican Secretary of Public Security Genaro Garcia Luna Convicted of Engaging in a Continuing Criminal Enterprise and Taking Millions in Cash Bribes from the Sinaloa Cartel,” U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of New York, February 21, 2023, https://www.justice.gov/usao-edny/pr/ex-mexican-secretary-public-security-genaro-garcia-luna-convicted-engaging-continuing. Such corruption means Mexico’s state capacity to fight the cartels is limited and any counterinsurgency strategy is likely to be futile.

Decapitation

Compared to counterinsurgency, decapitation—killing or apprehending the leader of an organization—has the benefits of immediate results at the tactical level. The United States has demonstrated high proficiency in these operations, particularly against terrorist groups like ISIS and al-Qaeda.42Examples include but are not limited to the 2006 killing of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the head of al-Qaeda in Iraq; the 2011 killing of al-Qaeda chief Osama Bin Laden; the 2019 raid on ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi; and the 2022 drone strike on al-Qaeda’s Ayman al-Zawahiri. The assumption behind them is that taking out the leadership will, over time, weaken a group’s capacity to organize, recruit, and conduct attacks, and render it inept over the long term.43Some scholars have tested these assumptions. In his study, Bryan Price concludes that “decapitated terrorist groups have a significantly higher mortality rate than nondecapitated groups.” Bryan Price, “Targeting Top Terrorists: How Leadership Decapitation Contributes to Counterterrorism,” International Security 36, no. 4 (2012): 9–46. Some U.S. defense officials are considering the use of this tactic against the cartels. Before he became defense secretary, Pete Hegseth advocated for “precision strikes” against cartel leaders in Mexico.44Samuel Gaytan, “Defense secretary nominee: US military strikes on Mexican cartels might be needed,” LoneStar Live, November 13, 2024, https://www.lonestarlive.com/news/2024/11/defense-secretary-nominee-us-military-strikes-on-mexican-cartels-might-be-needed.html.

But decapitating the cartels is not a new strategy, particularly in Mexico, where successive Mexican governments have relied on high-level targeting for the last two decades. As illustrated earlier in this paper, the Calderón and Peña Nieto administrations employed decapitation repeatedly throughout their tenures in what was called the “Kingpin Strategy.” Even AMLO, who adopted a less punitive approach to the cartels, still deployed Mexican special forces to cartel hideouts. Under AMLO, after a failed capture mission in 2019, Mexican forces arrested Ovidio Guzmán López, one of the sons of Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán Loera, in January 2023.45Natalie Kitroeff and Steve Fisher, “El Chapo’s Son Is Captured by Mexican Authorities for 2nd Time,” New York Times, January 5, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/05/world/americas/el-chapo-son-ovidio-guzman-mexico.html.

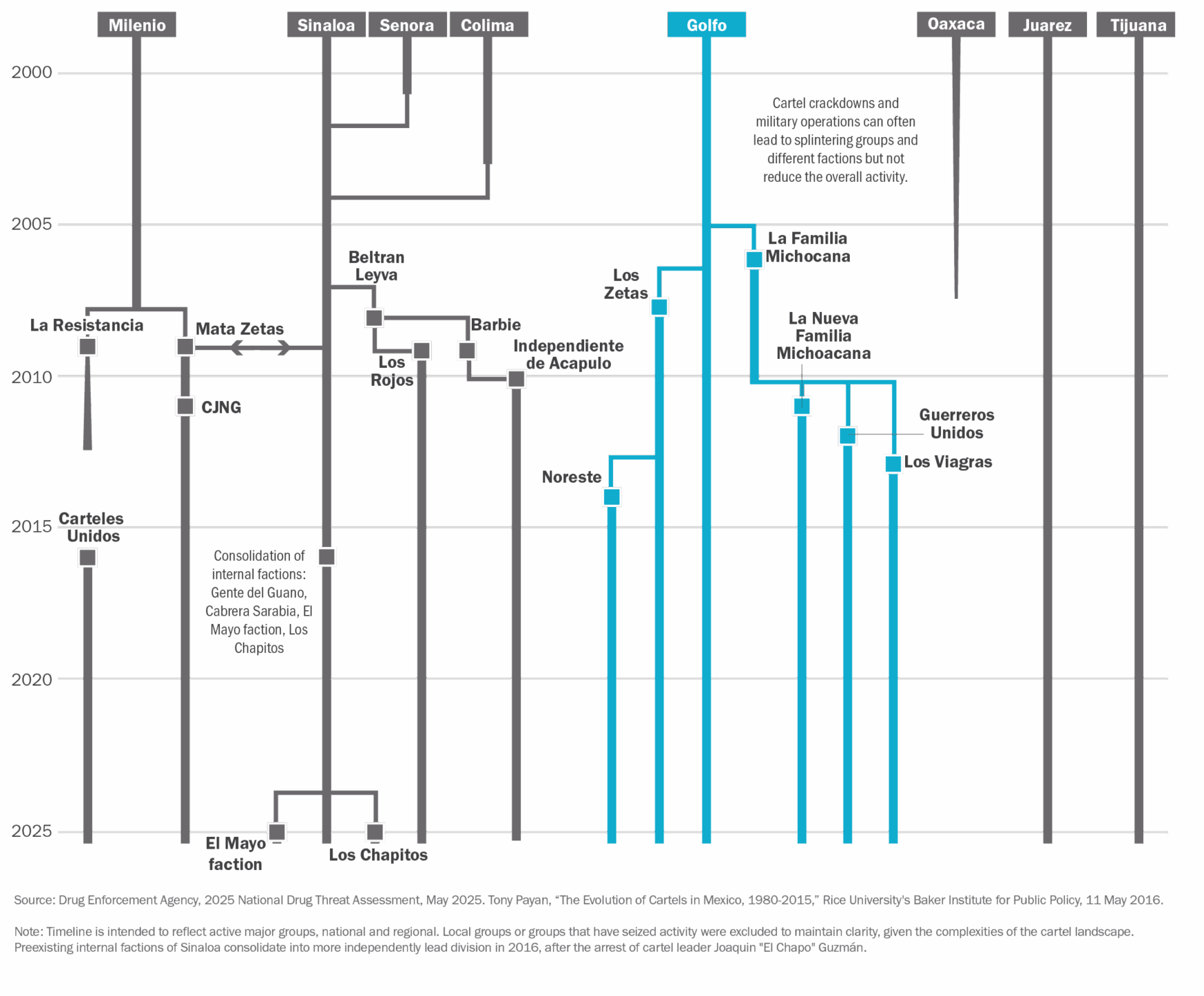

The results of the strategy are clear: while a high number of senior-level narcotraffickers were killed or arrested, ultimately this brought more violence, not less, and did not reduce drug trafficking. Far from eliminating these groups in their entirety, neutralizing a top narco-trafficker tends to scramble the group’s internal balance of power and gives ambitious players with less seniority the opening to grab more authority for themselves.

In some instances, smaller and locally based affiliates once tied to the larger cartels have successfully exploited the chaos associated with a leadership vacuum to increase their autonomy or become newly independent organizations. This is exactly what happened with the Jalisco New Generation Cartel, which used to be a sub-faction of another organization allied with the Sinaloa Cartel. It went its own way after successive leadership losses.46“The Expansion and Diversification of Mexican Cartels…” 34.

Today, thanks to Mexico’s reliance on decapitation, the cartel landscape is more diffuse and chaotic. Although the Sinaloa and Jalisco New Generation Cartels remain the most powerful, a constellation of smaller criminal enterprises—either working independently or in league with larger criminal outfits—has emerged. The number of criminal groups increased from fewer than 70 in 2010 to more than 200 in 2020, according to one study, a consequence of more established cartels splitting into multiple offshoots after their top leaders were eliminated and potential replacements battled amongst themselves for power.47“Crime in Pieces: The Effects of Mexico’s ‘War on Drugs,’ Explained,” International Crisis Group, May 4, 2022, https://www.crisisgroup.org/content/crime-pieces-effects-mexicos-war-drugs-explained#:~:text=Breaking%20the%20data%20down%20further,greatly%20in%20size%20and%20scope. Those smaller groups, in turn, fight one another for control of trafficking routes, urban centers, and the illicit economy, with violence spreading to areas that were once relatively peaceful.48Oscar Contreras Velasco, “Unintended consequences of state action: how the kingpin strategy transformed the structure of violence in Mexico’s organized crime,” Trends in Organized Crime 16, no.1 (July 2023), https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12117-023-09498-x.

The end result is a complication of the overall threat environment, putting more strain on the Mexican military and state as civilians increasingly question the government’s competence. This continues today: the Sinaloa Cartel is now in a state of civil war after one of its co-founders, Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada, was arrested by U.S. authorities.49Pablo Ferri, “The drug war bleeding Sinaloa,” El Pais, December 13, 2024, https://english.elpais.com/international/2024-12-14/the-drug-war-bleeding-sinaloa.html. The other faction of the Sinaloa Cartel, the so-called Chapitos, led by sons of former cartel head Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, have sought to take advantage of Zambada’s capture by increasing their hold over the entire organization, a typical response whenever leaders are removed.

While killing or arresting drug kingpins makes for good headlines and gives policymakers the illusion of progress, decapitation is unlikely to reduce drug flows into the United States. Unlike terrorist organizations, cartels are driven by financial motives rather than political goals or ideology, which means the highly profitable business of producing and smuggling drugs will continue regardless of who is at the top of the hierarchy.

Mexican drug cartels (2000–2025)

The evidence for this is strong: the demise of Pablo Escobar in 1993, for instance, did not negatively impact the cocaine trade to the United States. Instead, Escobar’s major competitor in Colombia, the Cali Cartel, simply took over the business.50Victor D. Hyder, “Decapitation Operations: Criteria for Targeting Enemy Leadership,” United States Army Command and General Staff College, 2014: 45–46. The fentanyl and synthetic opioid trade in Mexico will not be any different. As a 2010 assessment from U.S. Customs and Border Protection starkly asserted, “While the continued arrest or death of key DTO [drug trafficking organization] leadership may have long-term implications as to the control and viability of a specific DTO, there is no indication it will impact overall drug flows into the United States.”51“Drug Trafficking Organizations Adaptability to Smuggle Drugs across SWB after Losing Key Personnel,” U.S. Customs and Border Protection, 2010, https://info.publicintelligence.net/CBP-NoChangeDTOs.pdf.

None of this is surprising to scholars. Jenna Jordan finds that decapitation generally does not increase the chances of a terrorist group’s elimination and can actually produce adverse consequences, such as higher morale within the targeted group and the elevation of even more radical and violent replacements.52Jenna Jordan, Leadership Decapitation: Strategic Targeting of Terrorist Organizations (Redwood City: Stanford University Press, 2019). Studying the trajectories of 457 terrorist groups over a span of 100 years, Audrey Kurth Cronin finds that leadership decapitation can work, but only if the entity is small, hierarchal, and lacks a clear succession plan.53Audrey Kurth Cronin, How Terrorism Ends: Understanding the Decline and Demise of Terrorist Campaigns (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2009); Audrey Kurth Cronin, “Sinwar Is Dead, but Hamas Will Survive,” Foreign Affairs, October 19, 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/israel/yahya-sinwar-dead-hamas-will-survive-audrey-kurth-cronin. Drug cartels, as explained above, are even less willing to fold than terrorist groups are.

Bombing cartel infrastructure

When in his first term President Trump mused about launching missiles into Mexico to destroy the cartels’ fentanyl production facilities, the idea was quickly dismissed by his advisers. This is no longer the case. Calls for bombing raids on cartel infrastructure have gone mainstream. During the 2024 U.S. presidential election, nearly all the Republican candidates supported it.54“Why America’s Republicans want to bomb Mexico,” Economist, September 14, 2023,

https://www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2023/09/14/why-americas-republicans-want-to-bomb-mexico; Jonathan Swan et al, “Trump Wanted to Fire Missiles at Mexico, Now the G.O.P. Wants to Send Troops,” New York Times, October 3, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/03/us/politics/trump-mexico-cartels-republican.html.

The logic behind this policy recommendation is straightforward: fewer labs mean less supply, which in turn means fewer drugs entering the United States.

Yet these claims do not stand up to scrutiny. The Mexican government under President Claudia Sheinbaum is already attacking the supply side of the fentanyl trade to no discernable long-term effect. Pressured in part by the Trump administration’s tariff threats, Mexico has replaced the previous administration’s “hugs, not bullets” approach with more heavy-handed law enforcement operations. Approximately 644 labs were dismantled and two million pills seized by the Sheinbaum administration in its first four months.55Jacques Coste, “The Missing Elements in Sheinbaum’s Crime-Fighting Strategy,” America’s Quarterly, March 27, 2025, https://americasquarterly.org/article/the-missing-elements-in-sheinbaums-crime-fighting-strategy/.

But while operations like this may force cartels and smaller-scale producers to shut down their operations for a time, these organizations will adapt by establishing new labs in different locations as they have done in the past. And because fentanyl is easy to produce and does not require large tracts of land like cocaine or opium, its production sites may be hard for authorities to spot. Other producers will go to ground and resume their work once law enforcement actions cease or dwindle.

The recent air campaign the United States conducted against the Houthis in Yemen is illustrative—after about a year of bombing, the Trump administration concluded it could not destroy enough Houthi missiles and launchers to prevent their continued use (let alone coerce the Houthis to stop using them). Destroying drug labs from the air is even more difficult. It’s ultimately akin to a game of whack-a-mole.

The real problem with attacking fentanyl labs is that it does not affect demand. If appetite in the United States remains high and there is money to be made, then producers will continue to manufacture fentanyl.56Steven Dudley et al, “The Flow of Precursor Chemicals for Synthetic Drug Production in Mexico,” Insight Crime, May 2023, 9, https://insightcrime.org/investigations/chemical-precursors-mexico-synthetic-drug-meth-fentanyl/. And as long as significant profits are available, the incentive for young recruits to enter the business will remain high.57Steven Dudley et al, “The Flow of Precusor Chemicals…” 91–92.

Unfortunately, there are no signs those profits are decreasing. The fentanyl business remains extremely lucrative. According to an April 2023 indictment from the U.S. Justice Department against the Chapitos, $800 of precursor materials can manufacture more than 400,000 fentanyl pills for distribution.58United States of America v. Ivan Archivaldo Guzman Salazar et al, no. 23-crim-180 (Southern District of New York, April 4, 2023), 27, https://www.justice.gov/d9/press-releases/attachments/2023/04/14/u.s._v._salazar_et_al_indictment_1.pdf. At a mere 50 cents a pill on the street, the cartels can earn more than 250 times what they paid for in precursors. No amount of U.S. bombing will alter this market dynamic.

It should also be noted that taking out drug production sites from the air has been tried elsewhere to little avail. The Colombian army has destroyed thousands of cocaine processing labs over the years, yet Colombia remains the world’s top producer of cocaine. The United States in 2017–2018 sought to reduce the Taliban’s revenue in Afghanistan by attacking opium labs in Taliban-controlled areas.59General John W. Nicholson Jr., “Department of Defense Press Briefing by General Nicholson via teleconference from Kabul, Afghanistan,” Department of Defense, November 20, 2017,

https://www.defense.gov/News/Transcripts/Transcript/Article/1377753/department-of-defense-press-briefing-by-general-nicholson-via-teleconference-fr/.

The Defense Department’s Inspector General concluded that the air campaign, codenamed Operation Iron Tempest, failed to accomplish this objective, writing that “narcotics production in Afghanistan remained at elevated levels.”60General John W. Nicholson Jr., “Department of Defense Press Briefing…” Dr. David Mansfield, an expert on Afghanistan’s drug markets, arrived at a similar assessment, calling the impact of the U.S. operation on Taliban finances “negligible at best.”61David Mansfield, ”Bombing Heroin Labs in Afghanistan,” London School of Economics and Political Science, January 2018, 12, https://www.lse.ac.uk/united-states/Assets/Documents/Heroin-Labs-in-Afghanistan-Mansfield.pdf. And this campaign was against poppy fields, which are far easier to find and destroy than small labs.

A ‘plan Colombia’ for Mexico

The options described above center on U.S. kinetic action against the cartels. But the United States could also adopt a more indirect strategy of equipping the Mexican army to disrupt cartel operations on its own. This approach would not be novel. The George W. Bush and Barack Obama administrations were avid promoters of the Merida Initiative, which sought to professionalize the Mexican security forces, strengthen Mexico’s police, bolster the rule of law, and address the socioeconomic drivers of violence.62“The Merida Initiative,” U.S. Embassy in Mexico, September 7, 2021, https://mx.usembassy.gov/the-merida-initiative/; Eric Olson, “The Merida Imitative and Shared Responsibility in U.S.-Mexico Security Relations,” Wilson Quarterly (Winter 2017), https://www.wilsonquarterly.com/quarterly/after-the-storm-in-u-s-mexico-relations/the-m-rida-initiative-and-shared-responsibility-in-u-s-mexico-security-relations.

The United States implemented a similar strategy in Colombia during the Bill Clinton and George W. Bush administrations through a program called Plan Colombia, a $10 billion initiative that prioritized increasing the Colombian state’s presence in the countryside. The purpose was to pressure the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) into negotiating a peace agreement with the state and eliminating—or at least severely reducing—shipments of cocaine into the United States.63June S. Beittel, “Colombia: Background and U.S. Relations,” R43813, Congressional Research Service, December 16, 2021, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R43813.

Plan Colombia proved highly popular: supported by U.S. funds and equipment, the Colombian military significantly enhanced its ability to conduct offensives against the FARC in areas of the country that were previously off-limits.64Nick Miroff, “Plan Colombia: How Washington learned to love Latin American intervention again,” Washington Post, September 18, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/the_americas/plan-colombia-how-washington-learned-to-love-latin-american-intervention-again/2016/09/18/ddaeae1c-3199-4ea3-8d0f-69ee1cbda589_story.html?itid=lk_inline_manual_13. In 2016, the FARC signed an agreement with the Colombian government that compelled it to demilitarize and participate in the Colombian political system as a formal political party.

Yet while it’s indisputable that Plan Colombia forced the FARC into peace talks, it ultimately had little effect on the cocaine business. A 2008 government report found that the cultivation, production, and shipment of cocaine into the United States actually increased from 2000 to 2006 when Plan Colombia was in full effect.65“Plan Colombia: Drug Reduction Goals Were Not Fully Met, but Security Has Improved; U.S. Agencies Need More Detailed Plans for Reducing Assistance,” GAO-09-71, United States Government Accountability Office, October 2008, 17–22, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-09-71.pdf. The trend continues today, with the UN Office on Drugs and Crime reporting that cocaine production in Colombia has increased every year since 2013.66“Colombia: Potential cocaine production increased by 53 per cent in 2023,

according to new UNODC survey,” United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, October 14, 2024, https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/press/releases/2024/October/colombia_-potential-cocaine-production-increased-by-53-per-cent-in-2023–according-to-new-unodc-survey.html.

In 2024, the DEA assessed that 97 percent of the cocaine seized in the United States originated in Colombia.67“National Drug Threat Assessment 2024,” Drug Enforcement Administration (May 2024), 35, https://www.dea.gov/press-releases/2024/05/09/dea-releases-2024-national-drug-threat-assessment.

This is not surprising. After the FARC extricated itself from the drug trade, other groups sought to claim their share of the business.68Justin Logan and Daniel Raisbeck, “The U.S. Military Can’t Solve the Fentanyl Crisis,” Foreign Policy, September 8, 2023, https://www.cato.org/commentary/us-military-cant-solve-fentanyl-crisis; “Colombia: From ‘Total Peace’ to Local Peace,” International Crisis Group, January 30, 2025, https://www.crisisgroup.org/latin-america-caribbean/andes/colombia/colombia-total-peace-local-peace. The violence dropped for a time but saw an uptick after the 2016 peace agreement as factions opposed to diplomacy with the Colombian government splintered from the FARC and more established groups like the National Liberation Army (ELN) grew in size.69Adam Isacson, “A Long Way to Go: Implementing Colombia’s Peace Accord After Five Years,” Washington Office on Latin America, November 23, 2021, 20–44, https://www.wola.org/analysis/a-long-way-to-go-implementing-colombias-peace-accord-after-five-years/#id.z4umtiv0bv5n. The number of Colombians who live in territory where an armed group is present has risen by 70 percent since 2021, while the number of people displaced by violence is up by more than 40 percent.70“Colombia: Millions now living in conflict zones,” Norwegian Refugee Council, August 15, 2024,

https://www.nrc.no/news/2024/august/colombia-millions-now-living-in-conflict-zones.

Would a Plan Colombia-style operation have any more success in Mexico than it had in Colombia? The answer is no; in fact, it might fare worse. First, fentanyl is a synthetic drug immune to the eradication programs the Colombian government undertook against coca fields. Second, unlike the FARC or the ELN, the Mexican cartels do not have political objectives. This makes it far harder, if not impossible, for the Mexican government to entice them to lay down arms in exchange for political concessions and judicial leniency as the Colombian government did with the FARC. Finally, as mentioned earlier, the Merida Initiative, itself a kind of Plan Colombia for Mexico, has already been tried with little to show for it. Doubling down on a failed policy will lead to the same results.

Costs to the United States

While failing to suppress the drug trade and likely spreading violence inside Mexico, military strikes could also have counterproductive and even dangerous consequences for the United States.

Most worryingly, U.S. military action against the cartels could see retaliatory or spillover violence within the United States itself or against American citizens abroad, particularly among the 1.6 million U.S. citizens who reside in Mexico.71“U.S. Relations With Mexico: Bilateral Relations Fact Sheet,” U.S. Department of State, September 16, 2024, https://www.state.gov/u-s-relations-with-mexico/. While exact numbers of cartel members inside the United States are hard to come by, the DEA claims that distribution networks and cells have a presence in all 50 states, with particular concentrations in the southwest, on both coasts, and near the Great Lakes, the regions where most major U.S. cities are located.72“United States: Areas of Influence of Major Mexican Transnational Criminal Organizations,” DEA-DCT-DIR-065-15, Drug Enforcement Administration, July 2015, https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2018-07/dir06515.pdf; “National Drug Threat Assessment, 2024,” 1–3. Even a fraction of the violence the cartels carry out in Mexico—which includes assaults on federal and local police, assassinations of public officials, kidnappings, and car bombings—would radically change life for many Americans. American tourists in Mexico or neighboring countries could be easily kidnapped for ransom or killed, as they occasionally have been in the past.73When four American tourists were kidnapped and two killed in 2023, the Gulf cartel admitted responsibility and apologized; this would not have been the case if the U.S. were directly at war with the cartels. Ken Dilanian and Minyvonne Burke, “Gulf cartel apologizes after Americans are kidnapped and killed in Mexico,” NBC News, March 9, 2023, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/gulf-cartel-apologizes-americans-are-kidnapped-killed-mexico-rcna74242.

Violence of this kind, and the resulting panic, would likely bring further political instability to the United States. There is already significant anti-immigrant sentiment in the U.S., which would be badly exacerbated by cartel-related violence. As during the “Global War on Terror,” this could endanger civil liberties, victimize innocent Latin American communities where cartel members are embedded, and push the U.S. into doubling down on the use of military force—creating a spiral of bad results on both sides of the border.

By violating Mexico’s sovereignty, the United States would offend other Latin American states and could isolate itself diplomatically. This could make it more difficult for Washington to elicit cooperation on various issues, including counternarcotics cooperation. And it might provide competitors, such as China, with opportunities to increase their influence in the United States’ own neighborhood. Already chafing at the United States’ often heavy-handed hegemony, some Latin American nations—especially Brazil—have sought to cultivate closer economic and security ties with China and Russia to lessen their dependency on Washington.74“Section 2: China’s Influence in Latin America and the Caribbean,” in 2021 Report to Congress, U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, November 2021, 69–118, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2021-11/Chapter_1_Section_2–Chinas_Influence_in_Latin_America_and_the_Caribbean.pdf; Diana Roy, “China’s Growing Influence in Latin America,” Council on Foreign Relations, January 10, 2025, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/china-influence-latin-america-argentina-brazil-venezuela-security-energy-bri; Bryan Harris and Joe Leahy, “Lula vows partnership with China to ‘balance world geopolitics’,” Financial Times, April 15, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/766ed3aa-3f51-4035-8573-43254c9756d5.

At a minimum, military action across the border would tank relations with the Mexican government and inflame anti-Americanism inside Mexico. It could even increase popular support for the cartels, which would market themselves as defenders of Mexican sovereignty against a foreign interloper. Like her predecessor, Mexican President Sheinbaum has rejected unilateral U.S. military action inside Mexico, a stance that is supported by the opposition political parties.75Brendan O’Boyle, “Mexico president rebukes calls for U.S. military action against cartels as an ‘offense’,” Reuters, March 9, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/mexico-president-rejects-us-lawmakers-calls-military-intervention-against-2023-03-09/; “Mexico will not stand US ‘invasion’ in fight against cartels, president says,” Guardian, February 20, 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/feb/20/claudia-sheinbaum-trump-terrorism; “Mexico rejects unilateral US military action after report US is weighing strikes,” Reuters, April 8, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/mexico-would-reject-unilateral-us-military-action-after-drone-strike-report-2025-04-08/. Both Mexico and the U.S. engage in significant cooperation on counternarcotics, intelligence-sharing, law enforcement, and customs and border enforcement.76Stephen Coulthart and Guillermo Vázquez del Mercado, “Uncertain Times Ahead for U.S.-Mexico Intelligence Cooperation,” Lawfare, January 21, 2025, https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/uncertain-times-ahead-for-u.s.-mexico-intelligence-cooperation; Sigrid Arzt, “U.S.-Mexico Security Collaboration: Intelligence Sharing and Law Enforcement Cooperation,” in Shared Responsibility: U.S.–Mexico Policy Options for Confronting Organized Crime, eds. Eric L. Olson, David Shirk, and Andrew Selee (Washington, D.C.: Wilson Center, 2010), https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/publication/Chapter%2012-%20U.S.-Mexico%20Security%20Collaboration%2C%20Intelligence%20Sharing%20and%20Law%20Enforcement%20Cooperation.pdf; Nicholas Dockery, “Cartels, Corruption, and Fentanyl: How Can U.S.-Mexico Cooperation Address Shared Security Concerns?” Modern War Institute at West Point, November 5, 2024, https://mwi.westpoint.edu/cartels-corruption-and-fentanyl-how-can-us-mexico-cooperation-address-shared-security-concerns/. Violating Mexico’s red lines would sever cooperation on all of these issues, undermining the Trump administration’s wider agenda, particularly its attempts to stem illegal immigration.

As a recent precedent, when U.S. authorities arrested Mexico’s former defense secretary on drug charges in Los Angeles in 2020, Lopez Obrador passed a law limiting the government’s cooperation with DEA agents operating in Mexico.77David Agren, “Mexico: new security law strips diplomatic immunity from DEA agents,” Guardian, December 15, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/dec/15/mexico-security-law-dea-agents-us. Sensing that this could cause long-term problems for the U.S.-Mexico relationship, the United States later dropped the charges and sent the minister back to Mexico.78Kevin Sieff, Mary Beth Sheridan, and Matt Zapotosky, “U.S. agrees to drop charges against former Mexican defense minister,” Washington Post, November 17, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/the_americas/mexico-cienfuegos-drug-charges-dropped/2020/11/17/430bd056-291f-11eb-92b7-6ef17b3fe3b4_story.html.

It is also possible that increased violence in Mexico would spill into neighboring countries in Latin America.79For example, see Gary J. Hale, “Armed Confrontations and Forced Evacuation from Villages in Chiapas, Mexico: The Uncontrolled Southern Border with Guatemala,” Small Wars Journal, February 20, 2025, https://smallwarsjournal.com/2025/02/20/armed-confrontations-and-forced-evacuation-from-villages-in-chiapas-mexico-the-uncontrolled-southern-border-with-guatemala/. This is already happening to some degree: the exponential rise in drug-related violence in Ecuador, once one of the safest countries in Latin America, is in part fueled by Mexican cartels allying with local gangs.80January and February 2025 saw the highest homicide rates in Ecuador on record. Carrie Kahn, “Ecuador’s next president faces rampant drug violence and few resources to combat it,” NPR, April 12, 2025, https://www.npr.org/2025/04/12/nx-s1-5359427/ecuadors-next-president-faces-rampant-drug-violence-and-few-resources-to-combat-it. This expansion of violence could also worsen the economic conditions that produce recruits for criminal networks and result in a surge of migration to the United States.

Recommendations and alternatives

There is, unfortunately, no silver bullet to stop the flow of drugs into the United States and suppress cartel violence in Mexico. The key point here is that U.S. military action in Mexico would likely make the problem worse. There are, however, some approaches to mitigate the violence unleashed by cartels and the devastating flow of fentanyl into the United States. Moreover, existing law enforcement measures that are necessary, if not sufficient, to obstruct narcotrafficking should be maintained, rather than endangered by U.S. strikes.

The United States should pursue greater trilateral cooperation to disrupt the flow of so-called precursor chemicals from China that arrive at ports in Mexico and are produced into fentanyl and then smuggled into the United States.81Senator Rob Portman, “Addressing the Supply of Synthetic Drugs in the United States,” Minority Staff Policy Report, United States Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs (December 2022), 23–29, https://www.hsgac.senate.gov/wp-content/uploads/imo/media/doc/Fentanyl%20Synthetic%20Drugs%20Report%2063%20(FINAL)%20-%203.pdf. While China has taken a number of measures to crack down on fentanyl and the export of its precursor components, cooperation with the United States has fluctuated in response to growing Sino-American tensions.82Zongyuan Zoe Liu, “What Is China’s Role in Combating the Illegal Fentanyl Trade?” Council on Foreign Relations, September 12, 2024, https://www.cfr.org/expert-brief/what-chinas-role-combating-illegal-fentanyl-trade; David Pierson, “Fentanyl Rises Again, This Time as Trump’s Diplomatic Weapon Against China,” New York Times, November 26, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/11/26/world/asia/trump-china-tariff-fentanyl.html.

For example, in 2022, China suspended counternarcotics cooperation, among other U.S.-China working groups, after Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s ill-advised trip to Taiwan.83“International Narcotics Control Strategy Report, Vol. I: Drug and Chemical Control,” United States Department of State, March 2023, 102–104, https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/2023-INCSR-Vol-1-Drug-and-Chemical-Control.pdf. While bilateral efforts resumed with Chinese commitments to enforce export controls on pharmaceutical precursors and crack down on cartel-related money laundering, there is still room for improvement, including on counternarcotic intelligence-sharing, enforcing stronger regulations on nonscheduled precursor chemicals, and imposing “Know Your Customer” policies on Chinese supply firms.84Vanda Felbab-Brown, “US-China relations and fentanyl and precursor cooperation in 2024,” Brookings Institution, February 29, 2024, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/us-china-relations-and-fentanyl-and-precursor-cooperation-in-2024/. Today’s strained relations between the United States and China undermine this collaboration.

While law enforcement measures taken by both Mexico and the United States have not stamped out the cartels, they have degraded them and interdicted substantial amounts of narcotics. These efforts should continue and expand. U.S. President Joe Biden and Mexican President Lopez Obrador agreed to the Bicentennial Framework for Security, Public Health, and Safe Communities in 2022, which outlined a number of initiatives both countries could take to improve relations and increase cross-border cooperation.85“Summary of the Action Plan for U.S.-Mexico Bicentennial Framework for Security, Public Health, and Safe Communities,” U.S. Department of State, January 31, 2022, https://www.state.gov/summary-of-the-action-plan-for-u-s-mexico-bicentennial-framework-for-security-public-health-and-safe-communities/.

In recent years, Mexico has welcomed increased U.S. drone surveillance of cartel operations and U.S. special forces support for the Mexican military.86“Mexico president asks lawmakers to let US military trainers into Mexico,” Reuters, November 29, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/mexico-president-asks-lawmakers-let-us-military-trainers-into-mexico-2023-11-29/; “Mexico president says her government requested US surveillance drone flights,” AP News, February 19, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/mexico-us-trump-drones-cia-13af9277fbbbf6ff4dfd470efc9cb647. The United States should expand on these efforts by providing support to the Mexican police, such as training and anti-corruption programs, while similar initiatives could strengthen its notoriously cumbersome and ineffectual judicial institutions.87Shannon O’Neill, “Mexico’s Carnage Has No Military Solution,” Bloomberg, April 13, 2023, https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2023-04-13/mexico-s-carnage-has-no-military-solution. The United States should also help Mexico in its efforts to counteract cartel recruitment by providing financial and organizational support for social, educational, and economic development programs. Mexico should take primary responsibility for these efforts with the United States playing a supporting role.

The U.S. government could also reduce cartel-related violence if it effectively controlled border traffic, including disrupting the flow of guns from the United States into Mexico by better enforcing anti-trafficking laws. The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives estimates that 74 percent of the illegal guns in Mexico come from the United States, and according to a Mexican government survey, 2.5 million U.S. guns crossed the border during the 2010s.88“National Firearms Commerce and Trafficking Assessment (NFCTA): Protecting America from Trafficked Firearms, Vol. IV, Part VII,” Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, March 3, 2025, 1, https://www.atf.gov/firearms/docs/report/nfcta-volume-iv-part-vii-–-firearm-commerce-crime-guns-and-southwest-border/download. The illegal acquisition of U.S. arms, including military-grade weapons like .50 caliber rifles, allows narcotraffickers to outgun the Mexican state, preventing a legitimate monopoly on the use of violence to maintain the rule of law.89Kevin Sieff and Nick Miroff, “The Sniper Rifles Flowing to Mexican Cartels Show a Decade of U.S. Failure,” Washington Post, November 19, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/world/mexico-losing-control/mexico-drug-cartels-sniper-rifles-us-gun-policy/. Mexico should also improve security at its border and other ports of entry to reduce the flow of contraband.

Perhaps the most daunting but important long-term task for the United States is to deal with American demand for illicit drugs. In 2016, the RAND Corporation estimated the U.S. market for illicit drugs to be $150 billion (about $200 billion in 2025 dollars).90Gregory Midgette, et al., What America’s Users Spend on Illegal Drugs, 2006-2016 (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2019), xi, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR3140.html. Lawmakers should consider drug reform measures to reduce the demand for drugs in the United States, as well as funding for mental health and addiction treatments.

An easy solution that’s no solution

Given the persistence of the Mexican cartels and the human destruction wrought on both sides of the Rio Grande, military action may appear tempting. But as is so often the case, a complex problem with deep social, political, and economic causes cannot be solved by military force alone. Military strikes on Mexican cartels seem like an easy solution to a difficult problem; in reality, they are no solution at all and would make the problem worse.

U.S. military action in Mexico, regardless of what form it takes, will not stop the flow of drugs across the southern border. Instead, it will intensify the violence already engulfing Mexico and could spread it to the United States and beyond. The more difficult and less satisfying task of mitigating the problem in the short term, and addressing its roots over the long term, is the only way to adequately manage the crisis. The United States and Mexico are locked together in this challenge, which can only be resolved through bilateral collaboration not unilateral coercion.

Endnotes

- 1“Provisional Drug Overdose Data,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, May 15, 2025, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm.

- 2“Statement from CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control on Provisional 2024 Overdose Death Data,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, May 14, 2025, https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2025/2025-statement-from-cdcs-national-center-for-injury-prevention-and-control-on-provisional-2024.html.

- 3“National Drug Threat Assessment 2025,” Drug Enforcement Administration (May 2025), 5, 7,10, https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2025-05/2025%20National%20Drug%20Threat%20Assessment_Web%205-12-2025.pdf.

- 4Salvador Rizzo, “Do Mexican drug cartels make $500 billion a year?” Washington Post, June 24, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/06/24/do-mexican-drug-cartels-make-billion-year/.

- 5Rafael Prieto-Curiel, Gian Maria Campedelli, and Alejandro Hope, “Reducing Cartel Recruitment Is the Only Way to Lower Violence in Mexico,” Science 381, no. 6664 (September 21, 2023): 1312–1316, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adh2888.

- 6Mark Esper, one of Trump’s defense secretaries during his first term, writes in his memoir that Trump inquired whether the United States should shoot missiles into Mexico to destroy fentanyl labs, a request Esper advised against. Maggie Haberman, “Trump Proposed Launching Missiles Into Mexico to ‘Destroy the Drug Labs,’ Esper Says,” New York Times, May 5, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/05/us/politics/mark-esper-book-trump.html; Mark T. Esper, A Sacred Oath: Memoirs of a Secretary of Defense During Extraordinary Times (New York: HarperCollins, 2022). During his March 6 address to Congress, Trump declared that the United States was now waging war on the cartels just as the cartels have waged war on the United States. “Remarks by President Trump in Joint Session of Congress,” White House, March 4, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/remarks/2025/03/remarks-by-president-trump-in-joint-address-to-congress/. A month later, during an April 2025 call with Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum, Trump reportedly recommended having the U.S. military take the lead role in counter-narcotics operations on Mexican soil. Sheinbaum denied the request. José de Córdoba and Santiago Perez, “Trump, Mexico’s Sheinbaum Spar Over Drug Cartels,” Wall Street Journal, May 2, 2025, https://www.wsj.com/world/americas/trump-mexicos-sheinbaum-spar-over-drug-cartels-f3aae16c.

- 7“H.J Res 18, AUMF Cartel Influence Resolution,” U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, January 12, 2023, https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-joint-resolution/18/text; Charles Borla, “JD Vance in Tucson: Send in U.S. military ‘to battle with the Mexican drug cartels,’” Arizona Daily Star, October 22, 2024, https://tucson.com/news/local/government-politics/elections/tucson-rally-sen-jd-vance-gop-vp-candidate-border-cartels-military/article_661ef4e6-8d80-11ef-bb8e-1747a0dcaa25.html; José de Córdoba, Santiago Perez, and Vera Bergengruen, “Hegseth Warned of Military Action if Mexico Fails to Meet Trump’s Border Demands,” Wall Street Journal, February 28, 2025, https://www.wsj.com/politics/policy/trump-mexico-drug-cartel-tariff-hegseth-military-action-5f507ab0; Avery Lotz, “Mexican ambassador pick won’t rule out military strikes on cartels,” Axios, March 13, 2025, https://www.axios.com/2025/03/13/trump-mexico-ambassador-cartels-military-drone-strikes.

- 8“Total Elimination of Cartels and Transnational Criminal Organizations,” U.S. Department of Justice, February 5, 2025, https://www.justice.gov/ag/media/1388546/dl?inline.

- 9“Declaring a National Emergency at the Southern Border of the United States,” White House, January 20, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/declaring-a-national-emergency-at-the-southern-border-of-the-united-states/; “Designating Cartels and Other Organizations As Foreign Terrorist Organizations and Specially Designated Global Terrorists,” White House, January 20, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/designating-cartels-and-other-organizations-as-foreign-terrorist-organizations-and-specially-designated-global-terrorists/. The State Department officially listed six Mexican cartels as FTOs a month later. “Designation of International Cartels,” U.S. State Department, February 20, 2025, https://www.state.gov/designation-of-international-cartels/.

- 10Alex Horton and Hannah Natanson, “Secret Pentagon memo on China, homeland has Heritage fingerprints,” Washington Post, March 29, 2025, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/2025/03/29/secret-pentagon-memo-hegseth-heritage-foundation-china/.

- 11Julian E. Barnes, Marie Abi-Habib, Edward Wong, and Eric Schmitt, “C.I.A. Expands Secret Drone Flights Over Mexico,” New York Times, February 18, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/02/18/us/politics/cia-drone-flights-mexico.html.

- 12“The Medellín Cartel’s Future,” Drug Enforcement Administration, March 28, 1994, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/document/28748-document-13-pepes-annex-document-10-march-28-1994.

- 13Mónica Serrano, “States of Violence: State-Crime Relations in Mexico,” in W.G. Pansters, Violence, Coercion and State-Making in Twentieth-Century Mexico: The Other Half of the Centaur (Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press, 2012), 135–158.

- 14Viridiana Rios, “How government coordination controlled organized crime: The case of Mexico’s cocaine markets,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 59, no. 8 (2015): 1433–1454.

- 15Shannon O’Neil, ”The Real War in Mexico,” Foreign Affairs 88, no. 4 (2009): 63–77, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/mexico/2009-07-01/real-war-mexico.

- 16Jorge Castañeda, “Mexico’s Failed Drug War,” Cato Institute, May 6, 2010, https://www.cato.org/economic-development-bulletin/mexicos-failed-drug-war; Jo Tuckman, “Mexican drug cartels battle for power,” Guardian, February 1, 2004, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2004/feb/02/mexico.

- 17David A. Shirk, “The Drug War in Mexico,” no. 60, Council on Foreign Relations, March 2011, https://www.cfr.org/report/drug-war-mexico.

- 18Daniel Hernandez, “Calderon’s war on drug cartels: A legacy of blood and tragedy,” Los Angeles Times, December 1, 2012, https://www.latimes.com/world/la-xpm-2012-dec-01-la-fg-wn-mexico-calderon-cartels-20121130-story.html.

- 19“Peña Nieto’s Challenge: Criminal Cartels and Rule of Law in Mexico,” International Crisis Group, no. 48, March 19, 2013, https://www.crisisgroup.org/latin-america-caribbean/mexico/pena-nieto-s-challenge-criminal-cartels-and-rule-law-mexico.

- 20Patrick Corcoran, “A Legacy of Turmoil: Peña Nieto’s Tenure in Mexico,” Insight Crime, November 27, 2018, https://insightcrime.org/news/legacy-pena-nieto-mexico/; Elisabeth Malkin, “Mexico Strengthens Military’s Role in Drug War, Outraging Critics,” New York Times, December 15, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/15/world/americas/mexico-strengthens-militarys-role-in-drug-war-outraging-critics.html.

- 21June S. Beittel, “Mexico: Organized Crime and Drug Trafficking Organizations,” R41576, Congressional Research Service, June 7, 2022, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R41576.

- 22David Shirk, “AMLO, Violent Crime, and Public Security in Mexico,” Wilson Center, November 30, 2019, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/amlo-violent-crime-and-public-security-mexico.

- 23Jared Olson, “How AMLO Has Fueled Mexico’s Drug War,” Foreign Policy, June 23, 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/06/23/mexico-drug-war-amlo-lopez-obrador-demilitarization-national-guard-human-rights/.

- 24Rafael Croda, “AMLO’s six-year term exceeded 34.7% that of Peña Nieto in gun homicides,” Proceso, March 4, 2025, https://www.proceso.com.mx/nacional/2025/3/4/el-sexenio-de-amlo-supero-347-al-de-pena-nieto-en-homicidios-con-arma-de-fuego-346658.html.

- 25Vanda Felbab-Brown, “How the Sinaloa Cartel Rules,” Brookings Institution, April 4, 2022, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/how-the-sinaloa-cartel-rules/; José de Córdoba, “Mexico’s Cartels Distribute Coronavirus Aid to Win Popular Support,” Wall Street Journal, May 14, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/mexicos-cartels-distribute-coronavirus-aid-to-win-popular-support-11589480979.

- 26General Glen Vanherck, “USNORTHCOM-USSOUTHCOM Commander’s Joint Press Briefing Remarks,” U.S. Northern Command, March 16, 2021, https://www.northcom.mil/Newsroom/Transcripts/Transcript/Article/2542592/usnorthcom-ussouthcom-commanders-joint-press-briefing-remarks/.

- 27“A Conversation with U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton,” interviewed by Richard Haass, Council on Foreign Relations, September 8, 2010, https://www.cfr.org/event/conversation-us-secretary-state-hillary-rodham-clinton-2.

- 28Dan Crenshaw (@dancrenshawtx), “The cartels are an insurgency – mixing organized crime, terrorist acts, and occasional false benevolence to keep the population under control,” Instagram, January 2, 2025, https://www.instagram.com/dancrenshawtx/p/DEVTAD3zuO5/?img_index=1.

- 29Paul Dixon, “Hearts and Minds? British Counter-Insurgency from Malaya to Iraq,” Journal of Strategic Studies 32, no. 3: 353–381, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/01402390902928172.

- 30Previous counterinsurgency campaigns have often been brutal, repressive, and extremely violent. As Jacqueline Hazelton writes in her book Bullets Not Ballots, there have been numerous cases where the state chose to exploit its advantages in military power to coerce rather than persuade the population into rejecting anti-state forces. Jacqueline L. Hazelton, Bullets not Ballots: Success in Counterinsurgency Warfare (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2021).

- 31Christopher Paul, Colin P. Clarke, Beth Grill, and Molly Dunigan, “Paths to Victory: Detailed Insurgency Case Studies,” RAND, September 26, 2013, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR291z2.html.

- 32Christopher Paul et al, “Paths to Victory.”

- 33Ana Swanson, “How the Islamic State makes its money,” Washington Post, November 18, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2015/11/18/how-isis-makes-its-money/.